Strong CH…O Interactions in the Second Coordination Sphere of 1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes with Water

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

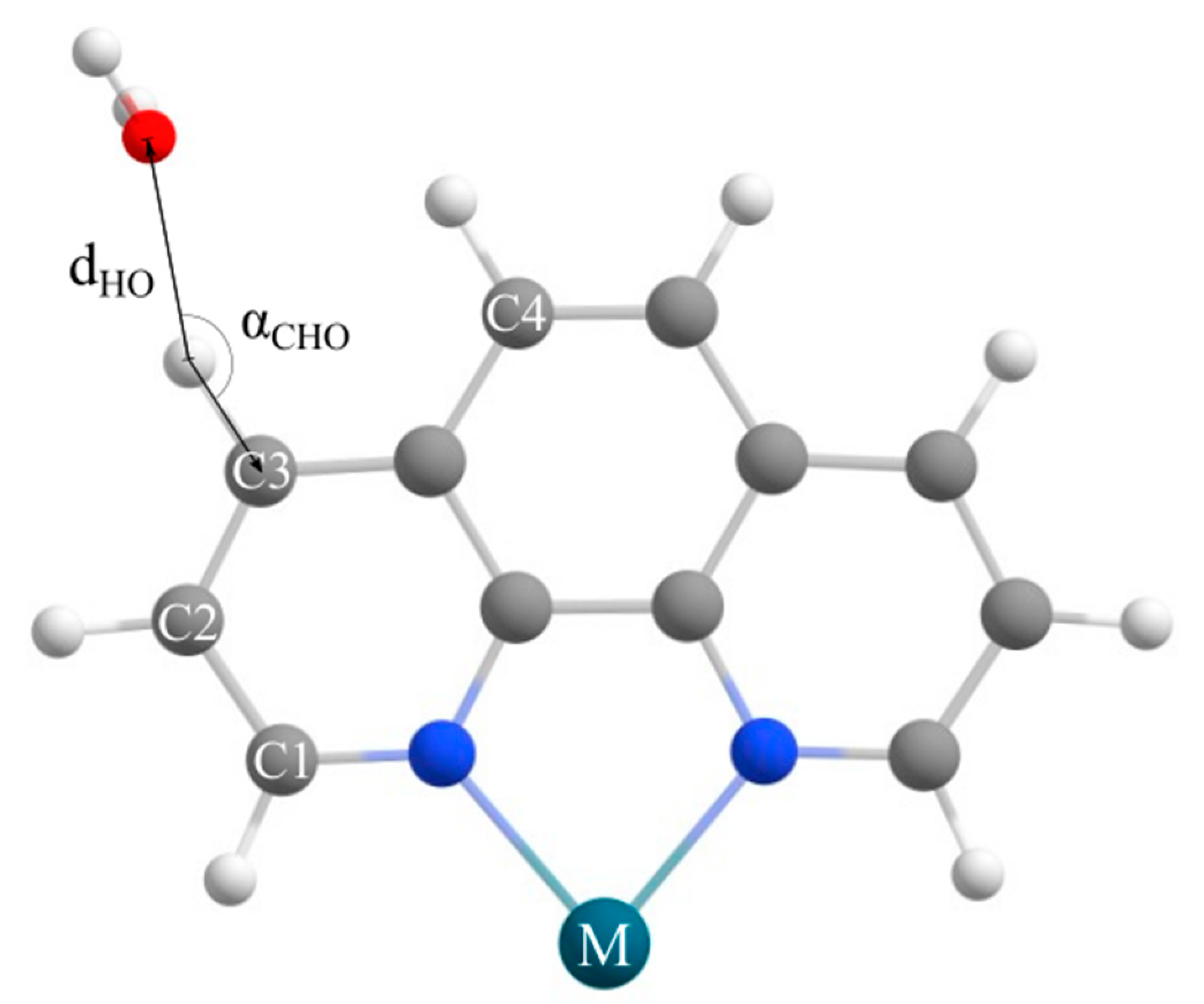

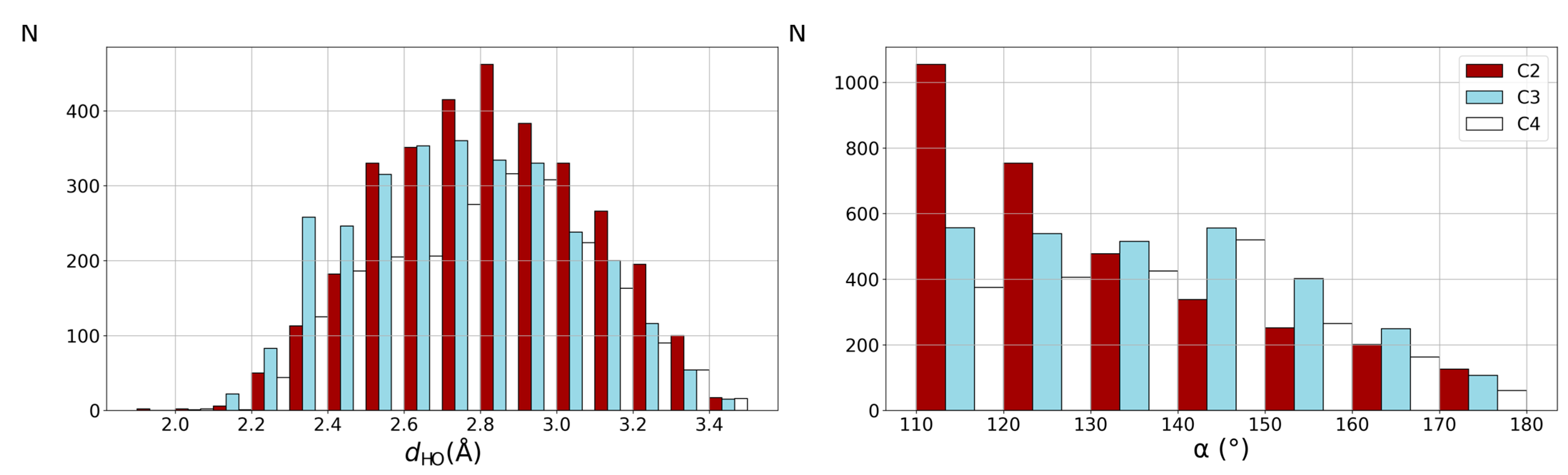

2.1. CSD Search Results

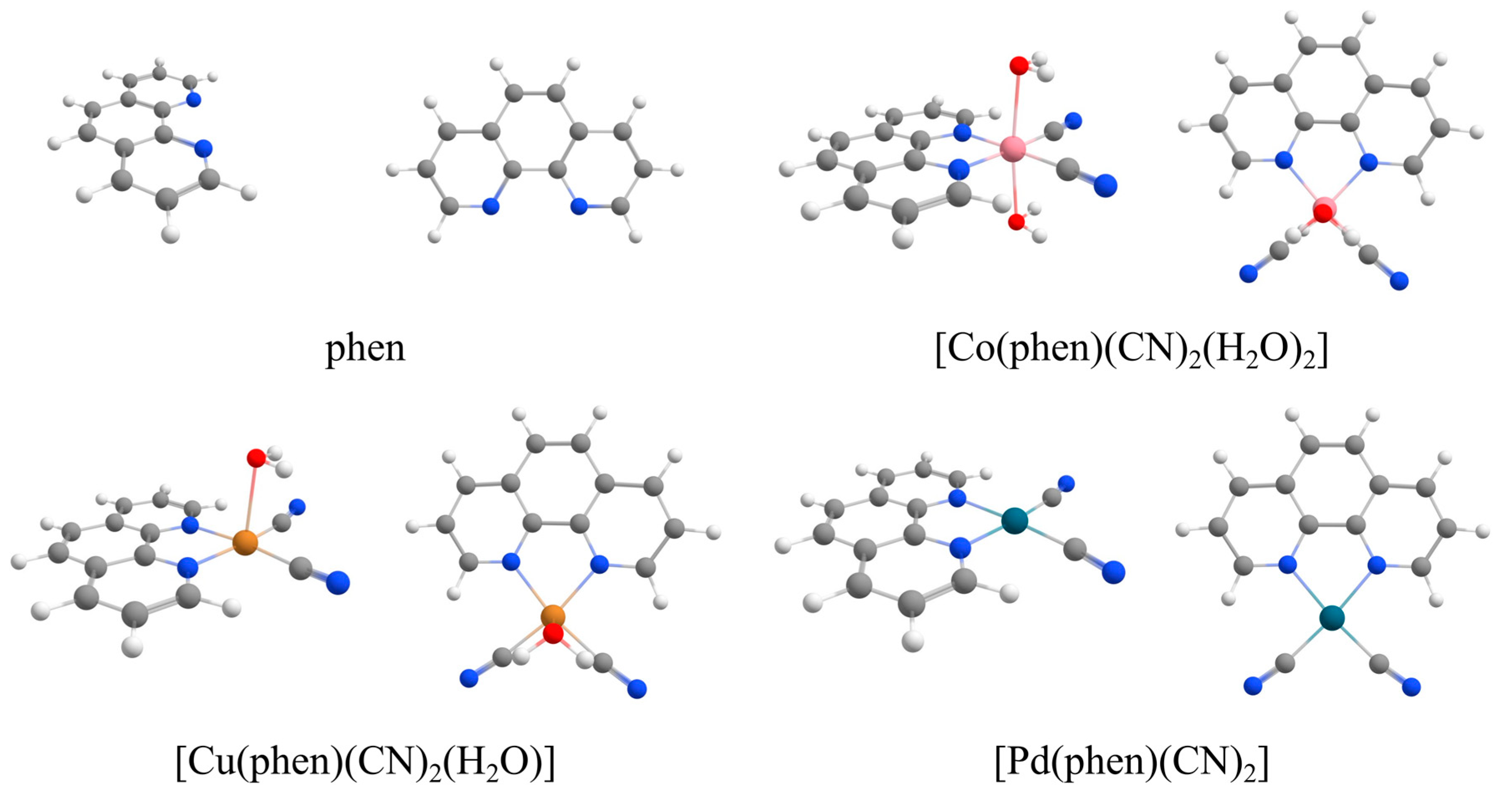

2.2. QM Calculations

3. Discussion

3.1. CSD Discussion

3.2. QM Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. CSD Search

4.2. QM Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| phen | 1,10-phenanthroline |

| bipy | 2,2′-bipyridine |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

| CCSDT | Coupled Cluster with Single, Double, and Triple Excitations |

| CBS | Complete Basis Set |

| DLPNO | Domain-based Local Pair Natural Orbital |

References

- Desiraju, G.R. The C-H···O Hydrogen Bond in Crystals: What Is It? Acc. Chem. Res. 1991, 24, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiraju, G.R. The C-H···O Hydrogen Bond: Structural Implications and Supramolecular Design. Acc. Chem. Res. 1996, 29, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, T. The Hydrogen Bond in the Solid State. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 48–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiraju, G.R.; Steiner, T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond: In Structural Chemistry and Biology; Oxford University Press, Inc.: Providence, RI, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-19-850252-4. [Google Scholar]

- Thirunavukkarasu, M.; Balaji, G.; Muthu, S.; Sakthivel, S.; Prabakaran, P.; Irfan, A. Theoretical Conformations Studies on 2-Acetyl-Gamma-Butyrolactone Structure and Stability in Aqueous Phase and the Solvation Effects on Electronic Properties by Quantum Computational Methods. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2022, 1208, 113534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragelj, J.L.; Janjić, G.V.; Veljković, D.Ž.; Zarić, S.D. Crystallographic and Ab Initio Study of Pyridine CH–O Interactions: Linearity of the Interactions and Influence of Pyridine Classical Hydrogen Bonds. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 10481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S.; Kar, T.; Pattanayak, J. Comparison of Various Types of Hydrogen Bonds Involving Aromatic Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13257–13264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigalov, M.V.; Doronina, E.P.; Sidorkin, V.F. C_(Ar)–H···O Hydrogen Bonds in Substituted Isobenzofuranone Derivatives: Geometric, Topological, and NMR Characterization. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 7718–7725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, V.; Fujii, A.; Mikami, N. A Study on Aromatic C–H···X (X = N, O) Hydrogen Bonds in 1,2,4,5-Tetrafluorobenzene Clusters Using Infrared Spectroscopy and Ab Initio Calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2005, 409, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthika, M.; Senthilkumar, L.; Kanakaraju, R. Theoretical Studies on Hydrogen Bonding in Caffeine–Theophylline Complexes. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2012, 979, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, J.M.; Janjić, G.V.; Ninković, D.B.; Zarić, S.D. The Influence of Water Molecule Coordination to a Metal Ion on Water Hydrogen Bonds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 10896–10898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrić, J.M.; Misini-Ignjatović, M.Z.; Murray, J.S.; Politzer, P.; Zarić, S.D. Hydrogen Bonding between Metal-Ion Complexes and Noncoordinated Water: Electrostatic Potentials and Interaction Energies. Chemphyschem 2016, 17, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malenov, D.P.; Živković, J.M.; Zarić, S.D. Hydrogen Bonds in the Second Coordination Sphere of Metal Complexes in the Gas Phase—Playing by the Rules? Dalt. Trans. 2025, 54, 12754–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živković, J.M.; Milovanović, M.R.; Zarić, S.D. Hydrogen Bonds of Coordinated Ethylenediamine and a Water Molecule: Joint Crystallographic and Computational Study of Second Coordination Sphere. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 5198–5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrilić, S.S.; Živković, J.M.; Zarić, S.D. Hydrogen Bonds of a Water Molecule in the Second Coordination Sphere of Amino Acid Metal Complexes: Influence of Amino Acid Coordination. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2023, 242, 112151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zrilić, S.S.; Živković, J.M.; Zarić, S.D. Computational and Crystallographic Study of Hydrogen Bonds in the Second Coordination Sphere of Chelated Amino Acids with a Free Water Molecule: Influence of Complex Charge and Metal Ion. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 251, 112442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninković, D.B.; Zivkovic, J.; Zarić, S. CH/O Hydrogen Bonds in the Second Coordination Sphere of Bipyridine Complexes with Water: Stronger than Classical Water–Water Hydrogen Bonds. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2025, 181, 115164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queffélec, C.; Pati, P.B.; Pellegrin, Y. Fifty Shades of Phenanthroline: Synthesis Strategies to Functionalize 1,10-Phenanthroline in All Positions. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6700–6902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencini, A.; Lippolis, V. 1,10-Phenanthroline: A Versatile Building Block for the Construction of Ligands for Various Purposes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2096–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreño, A.; Ancede-Gallardo, E.; Suárez, A.G.; Cepeda-Plaza, M.; Duque-Noreña, M.; Arce, R.; Gacitúa, M.; Lavín, R.; Inostroza, O.; Gil, F.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of a New Hydrogen-Bond-Stabilized 1,10-Phenanthroline–Phenol Schiff Base: Integrated Spectroscopic, Electrochemical, Theoretical Studies, and Antimicrobial Evaluation. Chemistry 2025, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boro, M.; Banik, S.; Gomila, R.M.; Frontera, A.; Barcelo-Oliver, M.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Supramolecular Assemblies in Mn(II) and Zn(II) Metal–Organic Compounds Involving Phenanthroline and Benzoate: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Inorganics 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordana, A.; Priola, E.; Mahmoudi, G.; Doustkhah, E.; Gomila, R.M.; Zangrando, E.; Diana, E.; Operti, L.; Frontera, A. Exploring Coinage Bonding Interactions in [Au(CN) 4 ]—Assemblies with Silver and Zinc Complexes: A Structural and Theoretical Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 5395–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, M.K.; Banik, S.; Baishya, T.; Sharma, P.; Dutta, K.K.; Gomila, R.M.; Barcelo-Oliver, M.; Frontera, A. Fascinating Inclusion of Metal–Organic Complex Moieties in Dinuclear Mn(II) and Zn(II) Compounds Involving Pyridinedicarboxylates and Phenanthroline: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Polyhedron 2024, 254, 116947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiekink, E.R.T. On the Coordination Role of Pyridyl-Nitrogen in the Structural Chemistry of Pyridyl-Substituted Dithiocarbamate Ligands. Crystals 2021, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, N.Y.; Okubazghi, T.H.; Abramov, P.A.; Rakhmanova, M.I.; Novikov, A.S.; Sokolov, M.N.; Gushchin, A.L. Asymmetric Coordination Mode of Phenanthroline-like Ligands in Gold(I) Complexes: A Case of the Antichelate Effect. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 3882–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, E.A.; Golubeva, Y.A.; Klyushova, L.S.; Smirnova, K.S.; Savinykh, P.E.; Romashev, N.F.; Gushchin, A.L.; Zaitsev, K.V.; Osik, N.A.; Fedin, M.V.; et al. Copper(II) Complexes Based on 2-Ferrocenyl-1,10-Phenanthroline: Structure, Redox Properties, Cytotoxicity and Apoptosis. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 17882–17894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, F.; Stefàno, E.; Migoni, D.; Iaconisi, G.N.; Muscella, A.; Marsigliante, S.; Benedetti, M.; Fanizzi, F.P. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Activity of Water-Soluble Cationic Organometallic Complexes of the Type [Pt(H1-C2H4OMe)(L)(Phen)]+ (L = NH3, DMSO; Phen = 1,10-Phenanthroline). Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ke, Z.; Yuan, L.; Liang, M.; Zhang, S. Hydrazylpyridine Salicylaldehyde–Copper(II)–1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes as Potential Anticancer Agents: Synthesis, Characterization and Anticancer Evaluation. Dalt. Trans. 2023, 52, 12318–12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinykh, P.E.; Golubeva, Y.A.; Smirnova, K.S.; Klyushova, L.S.; Berezin, A.S.; Lider, E.V. Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Cytotoxic Activity of 2,2′-Bipyridine/1,10-Phenanthroline Based Copper(II) Complexes with Diphenylphosphinic Acid. Polyhedron 2024, 261, 117141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ren, Y.; Jiang, H. Metal-Bipyridine/Phenanthroline-Functionalized Porous Crystalline Materials: Synthesis and Catalysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 438, 213907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionova, V.A.; Dmitrieva, A.V.; Abel, A.S.; Sergeev, A.D.; Evko, G.S.; Yakushev, A.A.; Gontcharenko, V.E.; Nefedov, S.E.; Roznyatovsky, V.A.; Cheprakov, A.V.; et al. Di(Pyridin-2-Yl)Amino-Substituted 1,10-Phenanthrolines and Their Ru(II)–Pd(II) Dinuclear Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization and Application in Cu-Free Sonogashira Reaction. Dalt. Trans. 2024, 53, 17021–17035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, F.N.; Rosko, M.C. Steric and Electronic Influence of Excited-State Decay in Cu(I) MLCT Chromophores. Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 2872–2886, Erratum in Acc. Chem. Res. 2024, 57, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, N.; Sato, K.; Handa, M.; Kataoka, Y. Electrochemical Hydrogen Evolution and Its Reaction Mechanism of Hydroxypyridinate-Bridged Dirhodium(II) Phenanthroline Complex. Catal. Today 2026, 462, 115542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakhvarov, D.G.; Petr, A.; Kataev, V.; Büchner, B.; Gómez-Ruiz, S.; Hey-Hawkins, E.; Kvashennikova, S.V.; Ganushevich, Y.S.; Morozov, V.I.; Sinyashin, O.G. Synthesis, Structure and Electrochemical Properties of the Organonickel Complex [NiBr(Mes)(Phen)] (Mes = 2,4,6-Trimethylphenyl, Phen = 1,10-Phenanthroline). J. Organomet. Chem. 2014, 750, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreja, P.; Kaur, N. Recent Advances in 1,10-Phenanthroline Ligands for Chemosensing of Cations and Anions. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 23169–23217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehleh, A.; Beghidja, A.; Beghidja, C.; Welter, R.; Kurmoo, M. Synthesis, Structures and Magnetic Properties of Dimeric Copper and Trimeric Cobalt Complexes Supported by Bridging Cinnamate and Chelating Phenanthroline. Comptes Rendus. Chim. 2015, 18, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, T.J.; Rujiwatra, A.; Chimupala, Y. [Ni(1,10-Phenanthroline)2(H2O)2](NO3)2: A Simple Coordination Complex with a Remarkably Complicated Structure That Simplifies on Heating. Crystals 2011, 1, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Sharma, R.P.; Ferretti, V.; Rossetti, S.; Venugopalan, P. Anion Binding through Second Sphere Coordination: Synthesis, Characterization and X-Ray Structures of Cationic Carbonato Bis (1, 10-Phenanthroline) Cobalt (III) Complex with Sulphur Oxoanions. J. Mol. Struct. 2009, 927, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Niu, Y.; Song, M.; Feng, Y.; Lu, J.; Tai, X. A Water-Stable Zn-MOF Used as Multiresponsive Luminescent Probe for Sensing Fe3+/Cu2+, Trinitrophenol and Colchicine in Aqueous Medium. Materials 2022, 15, 7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zheng, X.-J.; Jin, L.-P. A Microscale Multi-Functional Metal-Organic Framework as a Fluorescence Chemosensor for Fe (III), Al (III) and 2-Hydroxy-1-Naphthaldehyde. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2016, 471, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Wei, M.; Qi, W.; Li, X.; Niu, Y. A Stable and Highly Luminescent 3D Eu (III)-Organic Framework for the Detection of Colchicine in Aqueous Environment. Environ. Res. 2022, 208, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Yu, R.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, W.; Fu, X. Electrochemiluminescence Properties and Sensing Application of Zn (II)—Metal—Organic Frameworks Constructed by Mixed Ligands of Para Dicarboxylic Acids and 1, 10-Phenanthroline. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 43463–43473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.-H.; Du, M.-H.; Liu, J.; Jin, S.; Wang, C.; Zhuang, G.-L.; Kong, X.-J.; Long, L.-S.; Zheng, L.-S. Photo-Generated Dinuclear Eu (II) 2 Active Sites for Selective CO2 Reduction in a Photosensitizing Metal-Organic Framework. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, D.Ž.; Janjić, G.V.; Zarić, S.D. Are C–H···O Interactions Linear? The Case of Aromatic CH Donors. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, C.R.; Bruno, I.J.; Lightfoot, M.P.; Ward, S.C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, I.J.; Cole, J.C.; Edgington, P.R.; Kessler, M.; Macrae, C.F.; McCabe, P.; Pearson, J.; Taylor, R. New Software for Searching the Cambridge Structural Database and Visualizing Crystal Structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 2002, 58, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, M.R.; Živković, J.M.; Ninković, D.B.; Stanković, I.M.; Zarić, S.D. How Flexible Is the Water Molecule Structure? Analysis of Crystal Structures and the Potential Energy Surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 4138–4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. The ORCA Program System. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software Update: The ORCA Program System—Version 5.0. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Perdew, J.P.; Staroverov, V.N.; Scuseria, G.E. Climbing the Density Functional Ladder: Nonempirical Meta–Generalized Gradient Approximation Designed for Molecules and Solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. An Improvement of the Resolution of the Identity Approximation for the Formation of the Coulomb Matrix. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1740–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boys, S.F.; Bernardi, F. The Calculation of Small Molecular Interactions by the Differences of Separate Total Energies. Some Proced. Reduc. Errors. Mol. Phys. 1970, 19, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossmann, S.; Neese, F. Comparison of Two Efficient Approximate Hartee–Fock Approaches. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 481, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, C.; Neese, F. An Efficient and near Linear Scaling Pair Natural Orbital Based Local Coupled Cluster Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 034106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neese, F. The SHARK Integral Generation and Digestion System. J. Comput. Chem. 2023, 44, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neese, F.; Hansen, A.; Liakos, D.G. Efficient and Accurate Approximations to the Local Coupled Cluster Singles Doubles Method Using a Truncated Pair Natural Orbital Basis. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 064103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F.; Wennmohs, F.; Hansen, A. Efficient and Accurate Local Approximations to Coupled-Electron Pair Approaches: An Attempt to Revive the Pair Natural Orbital Method. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 114108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riplinger, C.; Sandhoefer, B.; Hansen, A.; Neese, F. Natural Triple Excitations in Local Coupled Cluster Calculations with Pair Natural Orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 134101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riplinger, C.; Pinski, P.; Becker, U.; Valeev, E.F.; Neese, F. Sparse Maps—A Systematic Infrastructure for Reduced-Scaling Electronic Structure Methods. II. Linear Scaling Domain Based Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 024109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bistoni, G.; Riplinger, C.; Minenkov, Y.; Cavallo, L.; Auer, A.A.; Neese, F. Treating Subvalence Correlation Effects in Domain Based Pair Natural Orbital Coupled Cluster Calculations: An Out-of-the-Box Approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 3220–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noga, J.; Bartlett, R.J. The Full CCSDT Model for Molecular Electronic Structure. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 7041–7050, Erratum in J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W.; Carroll, M.T.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Chang, C. Properties of Atoms in Molecules: Atomic Volumes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 7968–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, M.R.; Živković, J.M.; Ninković, D.B.; Zarić, S.D. Potential Energy Surfaces of Antiparallel Water-Water Interactions. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 389, 122758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| CH…O Type | Non-Coordinated Phen | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interacting C | dHO | ΔECC | ΔEB3LYP | VS |

| C2 | 2.4 | −2.09 | −2.05 | 18 |

| C3 | 2.3 | −2.57 | −2.53 | 22 |

| C4 | 2.4 | −2.44 | −2.37 | 20 |

| C1-C2 | 2.7 | −2.12 | −2.09 | / |

| C2-C3 | 2.7 | −2.34 | −2.28 | / |

| C3-C4 | 2.5 | −2.94 | −2.94 | / |

| C4-C4 | 2.7 | −2.32 | −2.13 | / |

| CH…O Type | Coordinated Phen | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coordination Number 6 [Co(phen)(CN)2(H2O)2] | Coordination Number 5 [Cu(phen)(CN)2(H2O)] | Coordination Number 4 [Pd(phen)(CN)2] | ||||||||||

| Interacting C | dHO | ΔECC | ΔEB3LYP | VS | dHO | ΔECC | ΔEB3LYP | VS | dHO | ΔECC | ΔEB3LYP | VS |

| C2 | 2.3 | −3.37 | −3.42 | 29 | 2.3 | −3.59 | −3.66 | 31 | 2.2 | −3.91 | −3.96 | 33 |

| C3 | 2.3 | −3.84 | −3.85 | 35 | 2.3 | −4.08 | −4.12 | 38 | 2.3 | −4.42 | −4.36 | 40 |

| C4 | 2.3 | −3.63 | −3.65 | 34 | 2.3 | −3.86 | −3.91 | 37 | 2.3 | −4.17 | −4.16 | 39 |

| C1-C2 | 2.5 | −3.57 | −3.53 | / | 2.5 | −3.77 | −3.82 | / | 2.5 | −4.37 | −4.30 | / |

| C2-C3 | 2.6 | −3.78 | −3.72 | / | 2.6 | −3.98 | −4.01 | / | 2.6 | −4.33 | −4.26 | / |

| C3-C4 | 2.5 | −4.35 | −4.41 | / | 2.5 | −4.61 | −4.70 | / | 2.5 | −4.94 | −4.96 | / |

| C4-C4 | 2.6 | −3.51 | −3.48 | / | 2.6 | −3.74 | −3.75 | / | 2.6 | −4.02 | −4.04 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zrilić, S.S.; Živković, J.M.; Ninković, D.B.; Zarić, S.D. Strong CH…O Interactions in the Second Coordination Sphere of 1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes with Water. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412100

Zrilić SS, Živković JM, Ninković DB, Zarić SD. Strong CH…O Interactions in the Second Coordination Sphere of 1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes with Water. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412100

Chicago/Turabian StyleZrilić, Sonja S., Jelena M. Živković, Dragan B. Ninković, and Snežana D. Zarić. 2025. "Strong CH…O Interactions in the Second Coordination Sphere of 1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes with Water" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412100

APA StyleZrilić, S. S., Živković, J. M., Ninković, D. B., & Zarić, S. D. (2025). Strong CH…O Interactions in the Second Coordination Sphere of 1,10-Phenanthroline Complexes with Water. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12100. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412100