Elevated MMP9 Expression—A Potential In Vitro Biomarker for COMPopathies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. D469del COMP HT1080 Cells Are an In Vitro Model of COMPopathy

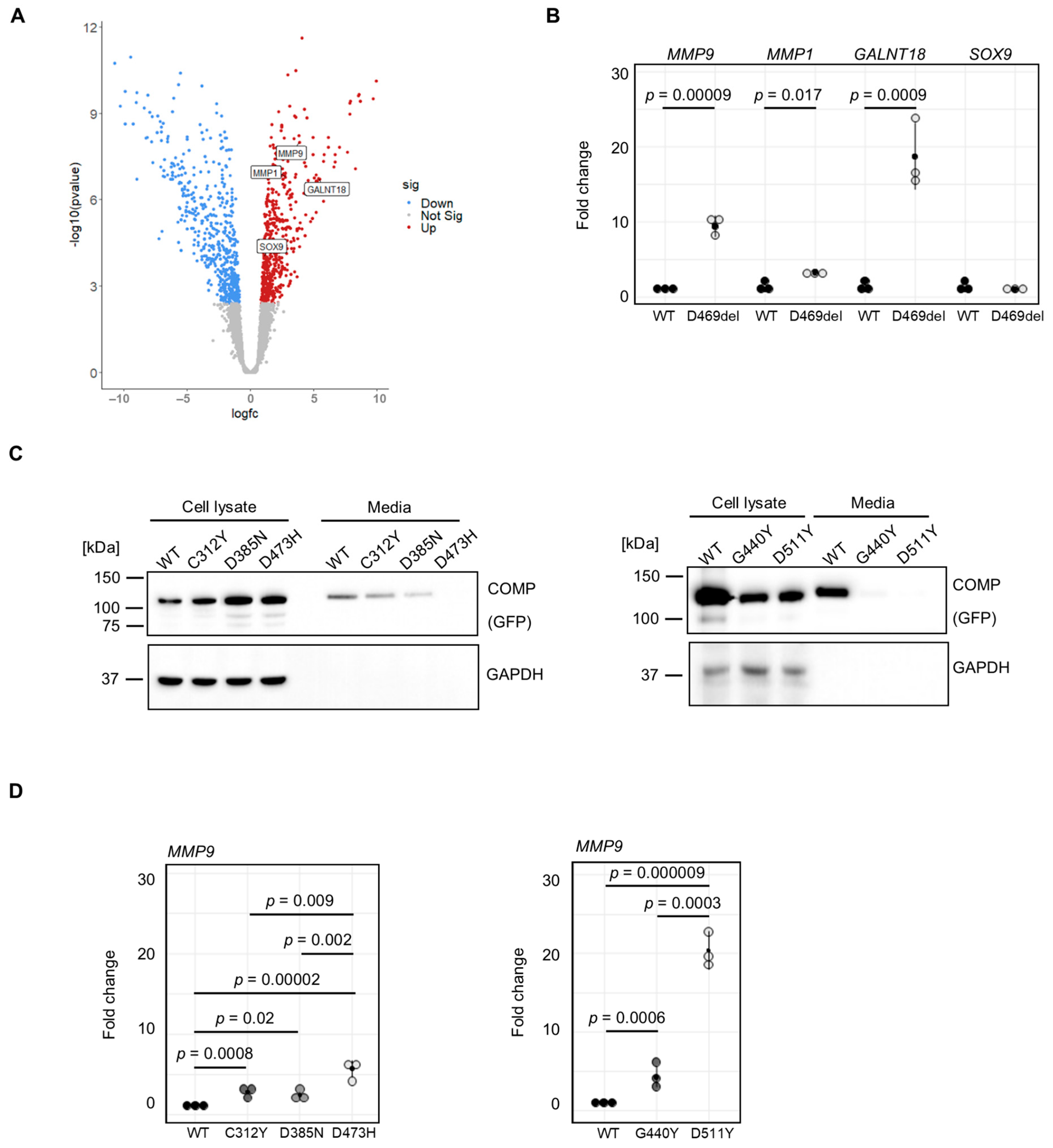

2.2. Transcriptomic Analysis of COMPopathy Cell Model

2.3. MMP9 Is Upregulated in Multiple COMPopathy Cell Models

2.4. A Disease-Causing Matrilin-3 Mutation Does Not Cause Increased MMP9 Expression

2.5. MMP9 Serum Levels in D469del COMP PSACH Mouse Model Are Not Altered

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Generation and Culture of Wild-Type and Mutant COMP Cell Lines

4.2. SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

4.3. TUNEL Assay

4.4. RNA Sequencing

4.5. Gene Expression Analysis by qRT-PCR

4.6. In-Gel Zymography

4.7. Serum MMP9 ELISA

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dodge, G.R.; Hawkins, D.; Boesler, E.; Sakai, L.; Jimenez, S.A. Production of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) by cultured human dermal and synovial fibroblasts. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 1998, 6, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedbom, E.; Antonsson, P.; Hjerpe, A.; Aeschlimann, D.; Paulsson, M.; Rosa-Pimentel, E.; Sommarin, Y.; Wendel, M.; Oldberg, A.; Heinegård, D. Cartilage matrix proteins. An acidic oligomeric protein (COMP) detected only in cartilage. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 6132–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K.; Zunino, L.; Webbon, P.M.; Heinegård, D. The distribution of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) in tendon and its variation with tendon site, age and load. Matrix Biol. 1997, 16, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haudenschild, D.R.; Hong, E.; Yik, J.H.; Chromy, B.; Mörgelin, M.; Snow, K.D.; Acharya, C.; Takada, Y.; Di Cesare, P.E. Enhanced activity of transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) bound to cartilage oligomeric matrix protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 43250–43258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, P.; Meadows, R.S.; Chapman, K.L.; Grant, M.E.; Kadler, K.E.; Briggs, M.D. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein interacts with type IX collagen, and disruptions to these interactions identify a pathogenetic mechanism in a bone dysplasia family. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6046–6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Acharya, C.; Christiansen, B.A.; Yik, J.H.; DiCesare, P.E.; Haudenschild, D.R. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein enhances osteogenesis by directly binding and activating bone morphogenetic protein-2. Bone 2013, 55, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.H.; Ozbek, S.; Engel, J.; Paulsson, M.; Wagener, R. Interactions between the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and matrilins. Implications for matrix assembly and the pathogenesis of chondrodysplasias. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 25294–25298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, K.; Olsson, H.; Mörgelin, M.; Heinegård, D. Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein shows high affinity zinc-dependent interaction with triple helical collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 20397–20403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, U.; Platz, N.; Becker, A.; Bruckner, P.; Paulsson, M.; Zaucke, F. A secreted variant of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein carrying a chondrodysplasia-causing mutation (p.H587R) disrupts collagen fibrillogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 63, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.D.; Hoffman, S.M.; King, L.M.; Olsen, A.S.; Mohrenweiser, H.; Leroy, J.G.; Mortier, G.R.; Rimoin, D.L.; Lachman, R.S.; Gaines, E.S.; et al. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia due to mutations in the cartilage oligomeric matrix protein gene. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.T.; Nelson, L.D.; Crowder, E.; Wang, Y.; Elder, F.F.; Harrison, W.R.; Francomano, C.A.; Prange, C.K.; Lennon, G.G.; Deere, M.; et al. Mutations in exon 17B of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) cause pseudoachondroplasia. Nat. Genet. 1995, 10, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.D.; Brock, J.; Ramsden, S.C.; Bell, P.A. Genotype to phenotype correlations in cartilage oligomeric matrix protein associated chondrodysplasias. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 22, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bönnemann, C.G.; Cox, G.F.; Shapiro, F.; Wu, J.J.; Feener, C.A.; Thompson, T.G.; Anthony, D.C.; Eyre, D.R.; Darras, B.T.; Kunkel, L.M. A mutation in the alpha 3 chain of type IX collagen causes autosomal dominant multiple epiphyseal dysplasia with mild myopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, K.L.; Mortier, G.R.; Chapman, K.; Loughlin, J.; Grant, M.E.; Briggs, M.D. Mutations in the region encoding the von Willebrand factor A domain of matrilin-3 are associated with multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Nat. Genet. 2001, 28, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarny-Ratajczak, M.; Lohiniva, J.; Rogala, P.; Kozlowski, K.; Perälä, M.; Carter, L.; Spector, T.D.; Kolodziej, L.; Seppänen, U.; Glazar, R.; et al. A mutation in COL9A1 causes multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: Further evidence for locus heterogeneity. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muragaki, Y.; Mariman, E.C.; van Beersum, S.E.; Perälä, M.; van Mourik, J.B.; Warman, M.L.; Olsen, B.R.; Hamel, B.C. A mutation in the gene encoding the alpha 2 chain of the fibril-associated collagen IX, COL9A2, causes multiple epiphyseal dysplasia (EDM2). Nat. Genet. 1996, 12, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paassilta, P.; Lohiniva, J.; Annunen, S.; Bonaventure, J.; Le Merrer, M.; Pai, L.; Ala-Kokko, L. COL9A3: A third locus for multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999, 64, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thur, J.; Rosenberg, K.; Nitsche, D.P.; Pihlajamaa, T.; Ala-Kokko, L.; Heinegård, D.; Paulsson, M.; Maurer, P. Mutations in cartilage oligomeric matrix protein causing pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia affect binding of calcium and collagen I, II, and IX. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 6083–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterill, S.L.; Jackson, G.C.; Leighton, M.P.; Wagener, R.; Mäkitie, O.; Cole, W.G.; Briggs, M.D. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia mutations in MATN3 cause misfolding of the A-domain and prevent secretion of mutant matrilin-3. Hum. Mutat. 2005, 26, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, C.L.; Edwards, S.; Mullan, L.; Bell, P.A.; Fresquet, M.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; Briggs, M.D. Armet/Manf and Creld2 are components of a specialized ER stress response provoked by inappropriate formation of disulphide bonds: Implications for genetic skeletal diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 5262–5275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, B.K.; Keene, D.R.; Sakai, L.Y.; Charbonneau, N.L.; Morris, N.P.; Ridgway, C.C.; Boswell, B.A.; Sussman, M.D.; Horton, W.A.; Bächinger, H.P.; et al. The fate of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein is determined by the cell type in the case of a novel mutation in pseudoachondroplasia. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 30993–30997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.L.; Posey, K.L.; Hecht, J.T.; Vertel, B.M. COMP mutations: Domain-dependent relationship between abnormal chondrocyte trafficking and clinical PSACH and MED phenotypes. J. Cell Biochem. 2008, 103, 778–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M.; Becker, A.; Schmitz, A.; Weirich, C.; Paulsson, M.; Zaucke, F.; Dinser, R. Disruption of extracellular matrix structure may cause pseudoachondroplasia phenotypes in the absence of impaired cartilage oligomeric matrix protein secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 32587–32595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L.H.; Rajpar, M.H.; Preziosi, R.; Briggs, M.D.; Boot-Handford, R.P. Increased classical endoplasmic reticulum stress is sufficient to reduce chondrocyte proliferation rate in the growth plate and decrease bone growth. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualeni, B.; Rajpar, M.H.; Kellogg, A.; Bell, P.A.; Arvan, P.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; Briggs, M.D. A novel transgenic mouse model of growth plate dysplasia reveals that decreased chondrocyte proliferation due to chronic ER stress is a key factor in reduced bone growth. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kaufman, R.J. Protein misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum as a conduit to human disease. Nature 2016, 529, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, M.D.; Dennis, E.P.; Dietmar, H.F.; Pirog, K.A. New developments in chondrocyte ER stress and related diseases. F1000Research 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, M.P.; Nundlall, S.; Starborg, T.; Meadows, R.S.; Suleman, F.; Knowles, L.; Wagener, R.; Thornton, D.J.; Kadler, K.E.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; et al. Decreased chondrocyte proliferation and dysregulated apoptosis in the cartilage growth plate are key features of a murine model of epiphyseal dysplasia caused by a matn3 mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007, 16, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nundlall, S.; Rajpar, M.H.; Bell, P.A.; Clowes, C.; Zeeff, L.A.; Gardner, B.; Thornton, D.J.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; Briggs, M.D. An unfolded protein response is the initial cellular response to the expression of mutant matrilin-3 in a mouse model of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Cell Stress Chaperones 2010, 15, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, P.A.; Wagener, R.; Zaucke, F.; Koch, M.; Selley, J.; Warwood, S.; Knight, D.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; Thornton, D.J.; Briggs, M.D. Analysis of the cartilage proteome from three different mouse models of genetic skeletal diseases reveals common and discrete disease signatures. Biol. Open 2013, 2, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Posey, K.L.; Coustry, F.; Veerisetty, A.C.; Liu, P.; Alcorn, J.L.; Hecht, J.T. Chop (Ddit3) is essential for D469del-COMP retention and cell death in chondrocytes in an inducible transgenic mouse model of pseudoachondroplasia. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 180, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, F.; Gualeni, B.; Gregson, H.J.; Leighton, M.P.; Piróg, K.A.; Edwards, S.; Holden, P.; Boot-Handford, R.P.; Briggs, M.D. A novel form of chondrocyte stress is triggered by a COMP mutation causing pseudoachondroplasia. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, K.L.; Coustry, F.; Veerisetty, A.C.; Hossain, M.; Alcorn, J.L.; Hecht, J.T. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory agents mitigate pathology in a mouse model of pseudoachondroplasia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 3918–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, L.A.; Mularczyk, E.J.; Kung, L.H.; Forouhan, M.; Wragg, J.M.; Goodacre, R.; Bateman, J.F.; Swanton, E.; Briggs, M.D.; Boot-Handford, R.P. Increased intracellular proteolysis reduces disease severity in an ER stress-associated dwarfism. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 3861–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tan, Z.; Niu, B.; Tsang, K.Y.; Tai, A.; Chan, W.C.W.; Lo, R.L.K.; Leung, K.K.H.; Dung, N.W.F.; Itoh, N.; et al. Inhibiting the integrated stress response pathway prevents aberrant chondrocyte differentiation thereby alleviating chondrodysplasia. eLife 2018, 7, e37673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.P.; Greenhalgh-Maychell, P.L.; Briggs, M.D. Multiple epiphyseal dysplasia and related disorders: Molecular genetics, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic avenues. Dev. Dyn. 2021, 250, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.P.; Watson, R.N.; McPate, F.; Briggs, M.D. Curcumin Reduces Pathological Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress through Increasing Proteolysis of Mutant Matrilin-3. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, A.; Lu, J.; Xu, Z.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, F.; Yang, F.; Sato, T.; Narimatsu, H.; et al. Polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase 18 non-catalytically regulates the ER homeostasis and O-glycosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, H.; Chaboissier, M.C.; Martin, J.F.; Schedl, A.; de Crombrugghe, B. The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 2813–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, J.T.; Veerisetty, A.C.; Wu, J.; Coustry, F.; Hossain, M.G.; Chiu, F.; Gannon, F.H.; Posey, K.L. Primary Osteoarthritis Early Joint Degeneration Induced by Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Is Mitigated by Resveratrol. Am. J. Pathol. 2021, 191, 1624–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Girolamo, N.; Indoh, I.; Jackson, N.; Wakefield, D.; McNeil, H.P.; Yan, W.; Geczy, C.; Arm, J.P.; Tedla, N. Human mast cell-derived gelatinase B (matrix metalloproteinase-9) is regulated by inflammatory cytokines: Role in cell migration. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; March, L.; Sambrook, P.N.; Jackson, C.J. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 by activated protein C: Relevance to inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 56, 2864–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, G.C.; Mittaz-Crettol, L.; Taylor, J.A.; Mortier, G.R.; Spranger, J.; Zabel, B.; Le Merrer, M.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Hall, C.M.; Offiah, A.; et al. Pseudoachondroplasia and multiple epiphyseal dysplasia: A 7-year comprehensive analysis of the known disease genes identify novel and recurrent mutations and provides an accurate assessment of their relative contribution. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duran, I.; Zieba, J.; Csukasi, F.; Martin, J.H.; Wachtell, D.; Barad, M.; Dawson, B.; Fafilek, B.; Jacobsen, C.M.; Ambrose, C.G.; et al. 4-PBA Treatment Improves Bone Phenotypes in the Aga2 Mouse Model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheiber, A.L.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Suzuki, A.; Enomoto-Iwamoto, M.; Kaito, T.; Cheah, K.S.; Iwamoto, M.; Leikin, S.; Otsuru, S. 4PBA reduces growth deficiency in osteogenesis imperfecta by enhancing transition of hypertrophic chondrocytes to osteoblasts. JCI Insight 2022, 7, e149636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, A.; Bal, B.S.; Ray, B.K. Transcriptional induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the chondrocyte and synoviocyte cells is regulated via a novel mechanism: Evidence for functional cooperation between serum amyloid A-activating factor-1 and AP-1. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 4039–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxfield, A.; Munkley, J.; Briggs, M.D.; Dennis, E.P. CRELD2 is a novel modulator of calcium release and calcineurin-NFAT signalling during osteoclast differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuleshov, M.V.; Jones, M.R.; Rouillard, A.D.; Fernandez, N.F.; Duan, Q.; Wang, Z.; Koplev, S.; Jenkins, S.L.; Jagodnik, K.M.; Lachmann, A.; et al. Enrichr: A comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W90–W97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dietmar, H.F.; Dennis, E.P.; Johnson de Sousa Brito, F.M.; Reynard, L.N.; Young, D.A.; Briggs, M.D. Elevated MMP9 Expression—A Potential In Vitro Biomarker for COMPopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412070

Dietmar HF, Dennis EP, Johnson de Sousa Brito FM, Reynard LN, Young DA, Briggs MD. Elevated MMP9 Expression—A Potential In Vitro Biomarker for COMPopathies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412070

Chicago/Turabian StyleDietmar, Helen F., Ella P. Dennis, Francesca M. Johnson de Sousa Brito, Louise N. Reynard, David A. Young, and Michael D. Briggs. 2025. "Elevated MMP9 Expression—A Potential In Vitro Biomarker for COMPopathies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412070

APA StyleDietmar, H. F., Dennis, E. P., Johnson de Sousa Brito, F. M., Reynard, L. N., Young, D. A., & Briggs, M. D. (2025). Elevated MMP9 Expression—A Potential In Vitro Biomarker for COMPopathies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412070