High Blood Levels of Cyclophilin A Increased Susceptibility to Ulcerative Colitis in a Transgenic Mouse Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

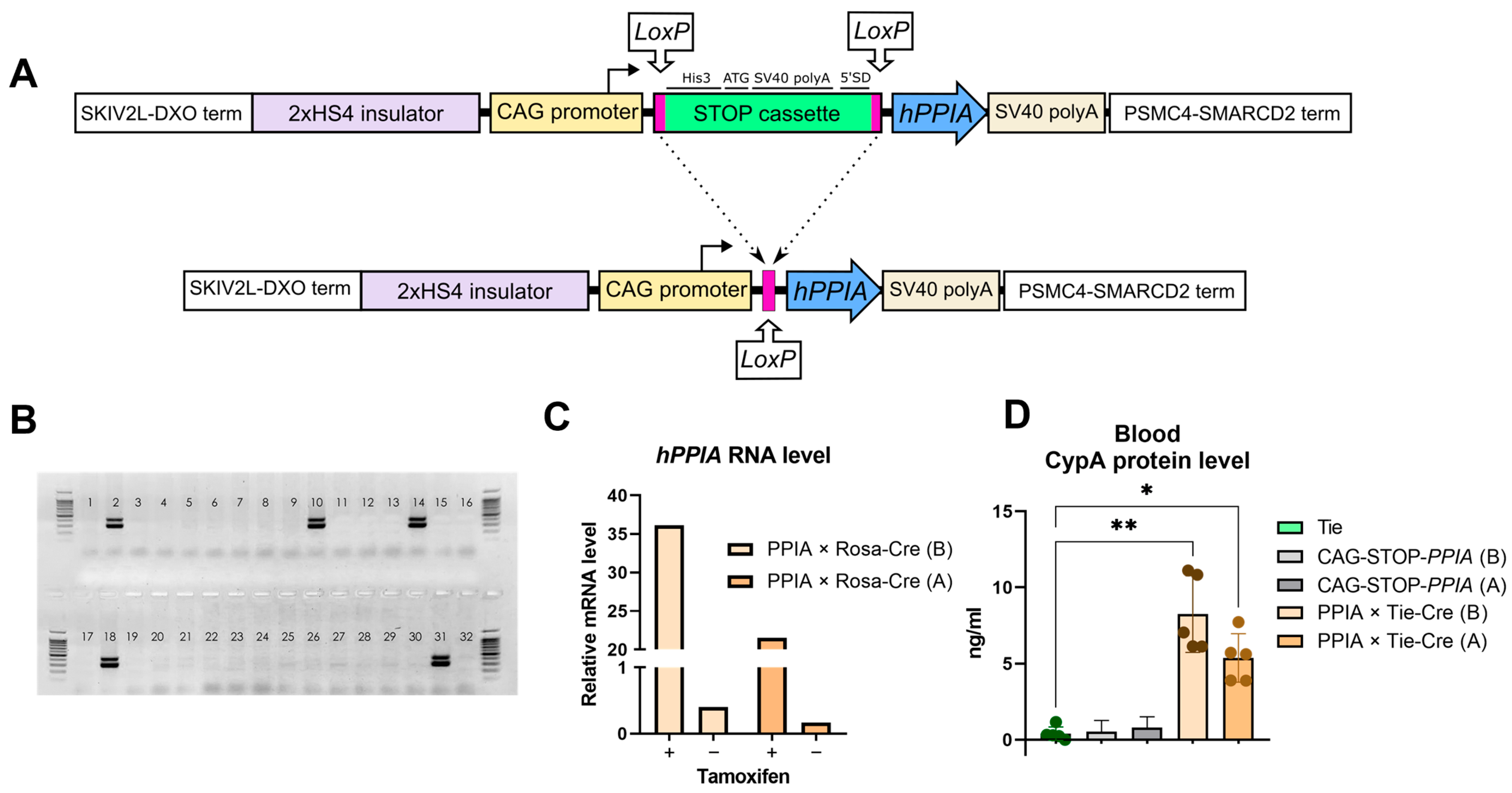

2.1. Transgene Generation and Validation

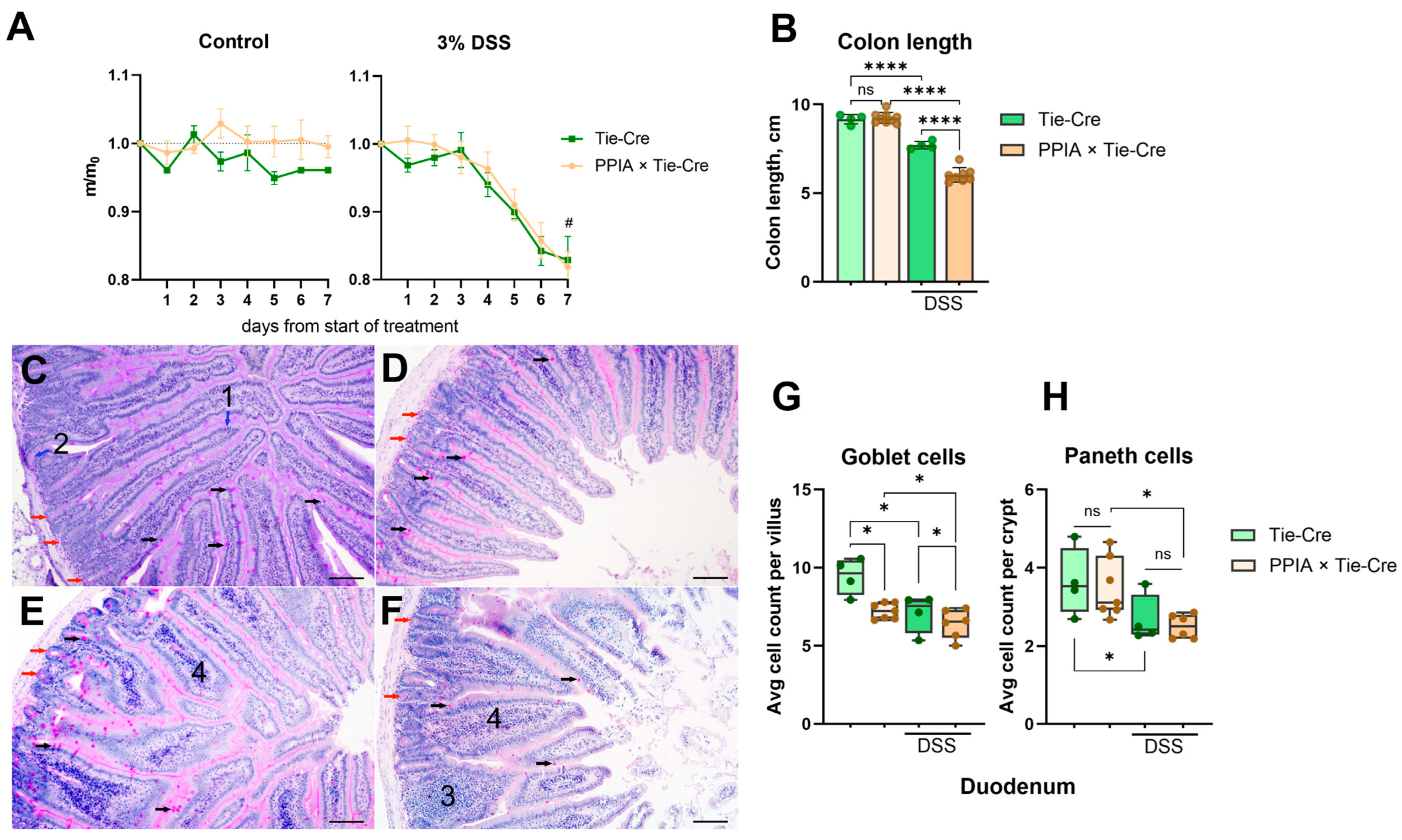

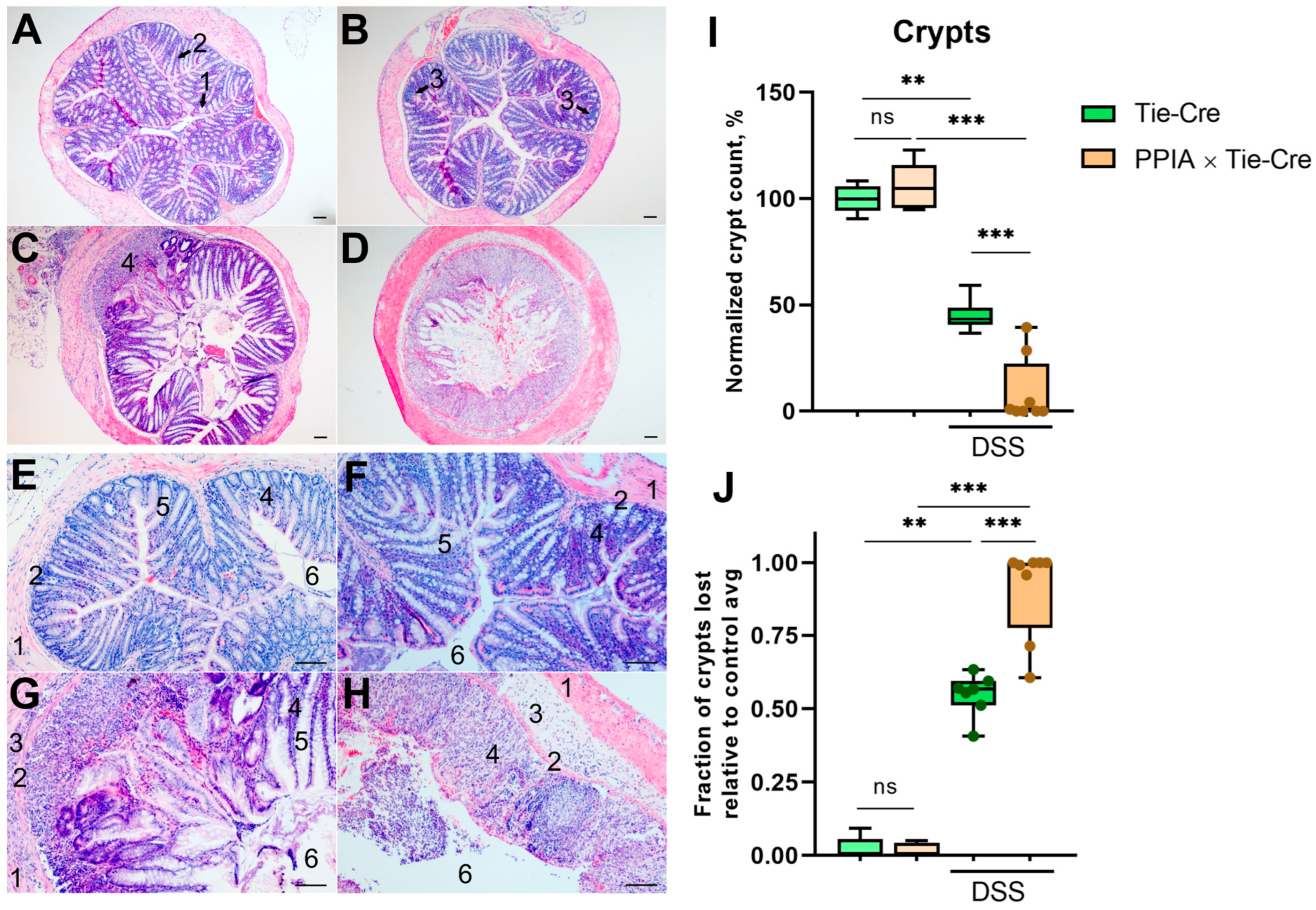

2.2. PPIA×Tie-Cre Mice Exhibited More Severe Symptoms of Ulcerative Colitis When Exposed to DSS

| Treatment | Scheme | Total/Deceased | DAI | Histological Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 7W 1 | 3/0 | 0 | None |

| 1% DSS | 7D + 7W | 5/0 | 0 | Duodenum: none Colon: local infiltration of l.p. 3 |

| 7D + 7W + 7D | 5/0 | 1 = 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 2 | Duodenum: slight l.p. swelling Colon: local infiltration of l.p. Crypt structure unaltered | |

| Water | 7W | 3/0 | 0 | None |

| 3% DSS | 7D + 7W | 5/0 | 3 = 1 + 1.5 + 0.5 + 0 | Duodenum: low Paneth and goblet cell counts, swelling of l.p Colon: chronic inflammation, l.p. infiltration, ⅓ crypts lost |

| 7D + 7W + 7D | 5/3 | 6 = 2 + 2.5 + 1 + 0.5 | Duodenum: low Paneth and goblet cell counts, swelling of l.p Colon: acute inflammation, extensive l.p. infiltration, 2/3 crypts lost | |

| Water | 7W | 3/0 | 0 | None |

| 5% DSS | 7D + 7W | 5/3 | 8 = 3 + 3 + 1 + 1 | Duodenum: low Paneth and goblet cell counts, swelling of l.p. Colon: acute inflammation, full loss of crypts |

| 7D + 7W + 7D | 5/5 | - | - |

| Score | Weight Loss | Stool Consistency | Rectal Bleeding | Anal Prolapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | loss < 1% | Separate hard lumps | No blood in stool | Not visible |

| 1 | 1% ≤ loss < 5% | Sausage-like with cracks | Blood in stool | Externally visible |

| 2 | 5% ≤ loss < 10% | Soft blobs | ||

| 3 | 10% ≤ loss <15% | Watery | ||

| 4 | loss ≥ 15% |

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Generation of Transgenic Mice

4.2. Husbandry

4.3. hPPIA Expression Measurements

4.4. Induction of Colitis

4.5. Histology

4.6. Statistical Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CypA | Cyclophilin A |

| CAG | Cytomegalovirus–actin–globin |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| NBF | Neutral buffered formalin |

| DSS | Dextran sulphate sodium |

References

- Song, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, Y. Evolving Understanding of Autoimmune Mechanisms and New Therapeutic Strategies of Autoimmune Disorders. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hracs, L.; Windsor, J.W.; Gorospe, J.; Cummings, M.; Coward, S.; Buie, M.J.; Quan, J.; Goddard, Q.; Caplan, L.; Markovinović, A.; et al. Global Evolution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across Epidemiologic Stages. Nature 2025, 642, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieujean, S.; Jairath, V.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Dubinsky, M.; Iacucci, M.; Magro, F.; Danese, S. Understanding the Therapeutic Toolkit for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 455, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2025, 22, 371-394.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, C.L.; Lefaudeux, D.; Mathenge, R.; Kishimoto, K.; Zuniga Munoz, A.; Nguyen, M.A.; Meyer, A.S.; Cheng, Q.J.; Hoffmann, A. A Stimulus-contingent Positive Feedback Loop Enables IFN-β Dose-dependent Activation of Pro-inflammatory Genes. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2023, 19, e11294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Sater, K.A. Physiological Positive Feedback Mechanisms. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 3, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutler, B. Microbe Sensing, Positive Feedback Loops, and the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Diseases. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 227, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, H.; Sato, T.; Tomaru, U.; Yoshida, M.; Utsunomiya, A.; Yamauchi, J.; Araya, N.; Yagishita, N.; Coler-Reilly, A.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Positive Feedback Loop via Astrocytes Causes Chronic Inflammation in Virus-Associated Myelopathy. Brain 2013, 136, 2876–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Bai, X.; Luan, X.; Min, J.; Tian, X.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Liu, W.; Fan, W.; et al. Delicate Regulation of IL-1β-Mediated Inflammation by Cyclophilin A. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, X.; Yang, W.; Bai, X.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Fan, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Sun, L. Cyclophilin A Is a Key Positive and Negative Feedback Regulator within Interleukin-6 Trans-signaling Pathway. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, K.; Gwinn, W.M.; Bower, M.A.; Watson, A.; Okwumabua, I.; MacDonald, H.R.; Bukrinsky, M.I.; Constant, S.L. Extracellular Cyclophilins Contribute to the Regulation of Inflammatory Responses. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, P.; Pompilio, G.; Capogrossi, M.C. Cyclophilin A: A Key Player for Human Disease. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, W.-J.; Jeon, S.-T.; Koh, E.-M.; Cha, H.-S.; Ahn, K.-S.; Lee, W.-H. Cyclophilin A May Contribute to the Inflammatory Processes in Rheumatoid Arthritis through Induction of Matrix Degrading Enzymes and Inflammatory Cytokines from Macrophages. Clin. Immunol. 2005, 116, 217–224, Erratum in Clin. Immunol. 2006, 119, 227.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billich, A.; Winkler, G.; Aschauer, H.; Rot, A.; Peichl, P. Presence of Cyclophilin A in Synovial Fluids of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 185, 975–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, M.; Qiao, X. Cyclophilin A: Promising Target in Cancer Therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2425127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota-Polanczyk, A.; Włodarczyk, M.; Sobolewska-Włodarczyk, A.; Jonakowski, M.; Pilarczyk, A.; Stec-Michalska, K.; Wiśniewska-Jarosińska, M.; Fichna, J. Serum Cyclophilin A Correlates with Increased Tissue MMP-9 in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis, but Not with Crohn’s Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 1511–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Lin, R.; Xie, Y.; Lin, H.; Shao, F.; Rui, W.; Chen, H. The Role of Cyclophilins in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2548–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaz, A.M.; Venu, N. Diagnostic Methods and Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, R.; Huang, L.; Xu, Y.; Su, M.; Chen, J.; Geng, L.; Xu, W.; Gong, S. CD147 Aggravated Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Triggering NF-κ B-Mediated Pyroptosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 5341247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, A.; Semenova, M.; Bruter, A.; Varlamova, E.; Kubekina, M.; Pavlenko, N.; Silaeva, Y.; Deikin, A.; Antoshina, E.; Gorkova, T.; et al. Cyclophilin A as a Pro-Inflammatory Factor Exhibits Embryotoxic and Teratogenic Effects during Fetal Organogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, C.; Wong, G.; Dong, W.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Gao, G.F.; Bi, Y.; et al. Cyclophilin A Protects Mice against Infection by Influenza A Virus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, F.; Lee, J.; Piao, Y.J.; Jae, Y.K.; Kim, Y.-J.; Oh, C.; Seo, J.-S.; Yun, Y.S.; Yang, C.W.; Ha, J.; et al. Transgenic Mice Overexpressing Cyclophilin A Are Resistant to Cyclosporin A-Induced Nephrotoxicity via Peptidyl-Prolyl Cis-Trans Isomerase Activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 316, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, K.; Matoba, T.; Suzuki, J.; O’Dell, M.R.; Nigro, P.; Cui, Z.; Mohan, A.; Pan, S.; Li, L.; Jin, Z.-G.; et al. Cyclophilin A Mediates Vascular Remodeling by Promoting Inflammation and Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Circulation 2008, 117, 3088–3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Nigro, P.; Zeidan, A.; Soe, N.N.; Jaffré, F.; Oikawa, M.; O’Dell, M.R.; Cui, Z.; Menon, P.; Lu, Y.; et al. Cyclophilin A Promotes Cardiac Hypertrophy in Apolipoprotein E–Deficient Mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1116–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seizer, P.; Ochmann, C.; Schönberger, T.; Zach, S.; Rose, M.; Borst, O.; Klingel, K.; Kandolf, R.; MacDonald, H.R.; Nowak, R.A.; et al. Disrupting the EMMPRIN (CD147)–Cyclophilin A Interaction Reduces Infarct Size and Preserves Systolic Function After Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, X.; Di, W.; Wang, C. Inhibitors of Cyclophilin A: Current and Anticipated Pharmaceutical Agents for Inflammatory Diseases and Cancers. Molecules 2024, 29, 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Dong, R.; Wang, J.; Pan, Y.; Cao, Y. Establishment of a Mouse Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Using Dextran Sulfate Sodium. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 32, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dan, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Exploration of Berberine Against Ulcerative Colitis via TLR4/NF-κB/HIF-1α Pathway by Bioinformatics and Experimental Validation. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 2847–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałużna, A.; Olczyk, P.; Komosińska-Vassev, K. The Role of Innate and Adaptive Immune Cells in the Pathogenesis and Development of the Inflammatory Response in Ulcerative Colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, U.; Zhang, R.; Yang, H.; Li, M.; Doan, L.X.; Chen, C.; Yao, Q. Effects of Cyclophilin A on Myeloblastic Cell Line KG-1 Derived Dendritic Like Cells (DLC) Through P38 MAP Kinase Activation1,2. J. Surg. Res. 2005, 127, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dongsheng, Z.; Zhiguang, F.; Junfeng, J.; Zifan, L.; Li, W. Cyclophilin A Aggravates Collagen-Induced Arthritis via Promoting Classically Activated Macrophages. Inflammation 2017, 40, 1761–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinina, A.A.; Tilova, L.R.; Kazansky, D.B.; Khromykh, L.M. Secreted Cyclophilin A Regulates the Development of Adaptive Immune Response by Modulating B and T Cell Functional Activity in Experimental Models in Vivo and in Vitro. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2025, 117, qiaf089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsker, J.M.; Bukrinsky, M.I.; Constant, S.L. Preferential Chemotaxis of Activated Human CD4+ T Cells by Extracellular Cyclophilin A. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 82, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 765474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Actis, G.C.; Pellicano, R. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Efficient Remission Maintenance Is Crucial for Cost Containment. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 8, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, O.H.; Ainsworth, M.A. Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizoguchi, A.; Takeuchi, T.; Himuro, H.; Okada, T.; Mizoguchi, E. Genetically Engineered Mouse Models for Studying Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pathol. 2016, 238, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Merlin, D. Unveiling Colitis: A Journey through the Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Model. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaska, J.M.; Balev, M.; Ding, Q.; Heller, B.; Ploss, A. Differences across Cyclophilin A Orthologs Contribute to the Host Range Restriction of Hepatitis C Virus. eLife 2019, 8, e44436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurchenko, V.; Constant, S.; Eisenmesser, E.; Bukrinsky, M. Cyclophilin-CD147 Interactions: A New Target for Anti-Inflammatory Therapeutics. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 160, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts-Thomson, I.C.; Bryant, R.V.; Costello, S.P. Uncovering the Cause of Ulcerative Colitis. JGH Open 2019, 3, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruter, A.V.; Korshunova, D.S.; Kubekina, M.V.; Sergiev, P.V.; Kalinina, A.A.; Ilchuk, L.A.; Silaeva, Y.Y.; Korshunov, E.N.; Soldatov, V.O.; Deykin, A.V. Novel Transgenic Mice with Cre-Dependent Co-Expression of GFP and Human ACE2: A Safe Tool for Study of COVID-19 Pathogenesis. Transgenic Res. 2021, 30, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavskaya, N.; Ilchuk, L.; Okulova, Y.; Kubekina, M.; Varlamova, E.; Silaeva, Y.; Bruter, A. Transgenic Mice for Study of the CDK8/19 Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Kinase-Independent Mechanisms of Action. Bull. RSMU 2022, 6, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruter, A.V.; Varlamova, E.A.; Stavskaya, N.I.; Antysheva, Z.G.; Manskikh, V.N.; Tvorogova, A.V.; Korshunova, D.S.; Khamidullina, A.I.; Utkina, M.V.; Bogdanov, V.P.; et al. Knockout of Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 8 and 19 Leads to Depletion of Cyclin C and Suppresses Spermatogenesis and Male Fertility in Mice. eLife 2025, 13, RP96465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisanuki, Y.Y.; Hammer, R.E.; Miyazaki, J.; Williams, S.C.; Richardson, J.A.; Yanagisawa, M. Tie2-Cre Transgenic Mice: A New Model for Endothelial Cell-Lineage Analysis in Vivo. Dev. Biol. 2001, 230, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A.; Kirsch, D.G.; McLaughlin, M.E.; Tuveson, D.A.; Grimm, J.; Lintault, L.; Newman, J.; Reczek, E.E.; Weissleder, R.; Jacks, T. Restoration of P53 Function Leads to Tumour Regression in Vivo. Nature 2007, 445, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubekina, M.; Kalinina, A.; Korshunova, D.; Bruter, A.; Silaeva, Y. Models of Mitochondrial Dysfunction with Inducible Expression of Polg Pathogenic Mutant Variant. Bull. RSMU 2022, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, S.; Takuma, S.; Morimoto, M. Histological Analysis of Murine Colitis Induced by Dextran Sulfate Sodium of Different Molecular Weights. Exp. Anim. 2000, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.; McKean, E.L.; Hawdon, J.M. Mini-Baermann Funnel, a Simple Device for Cleaning Nematode Infective Larvae. J. Parasitol. 2022, 108, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baikova, I.P.; Ilchuk, L.A.; Kubekina, M.V.; Kalinina, A.A.; Khromykh, L.M.; Okulova, Y.D.; Pavlenko, N.G.; Korshunova, D.S.; Korshunov, E.N.; Bruter, A.V.; et al. High Blood Levels of Cyclophilin A Increased Susceptibility to Ulcerative Colitis in a Transgenic Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412068

Baikova IP, Ilchuk LA, Kubekina MV, Kalinina AA, Khromykh LM, Okulova YD, Pavlenko NG, Korshunova DS, Korshunov EN, Bruter AV, et al. High Blood Levels of Cyclophilin A Increased Susceptibility to Ulcerative Colitis in a Transgenic Mouse Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412068

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaikova, Iuliia P., Leonid A. Ilchuk, Marina V. Kubekina, Anastasiia A. Kalinina, Ludmila M. Khromykh, Yulia D. Okulova, Natalia G. Pavlenko, Diana S. Korshunova, Eugenii N. Korshunov, Alexandra V. Bruter, and et al. 2025. "High Blood Levels of Cyclophilin A Increased Susceptibility to Ulcerative Colitis in a Transgenic Mouse Model" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412068

APA StyleBaikova, I. P., Ilchuk, L. A., Kubekina, M. V., Kalinina, A. A., Khromykh, L. M., Okulova, Y. D., Pavlenko, N. G., Korshunova, D. S., Korshunov, E. N., Bruter, A. V., & Silaeva, Y. Y. (2025). High Blood Levels of Cyclophilin A Increased Susceptibility to Ulcerative Colitis in a Transgenic Mouse Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412068