Region-Specific Expression Patterns of lncRNAs in the Central Nervous System: Cross-Species Comparison and Functional Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Constitutive lncRNA Expression Across the Murine Central Nervous System

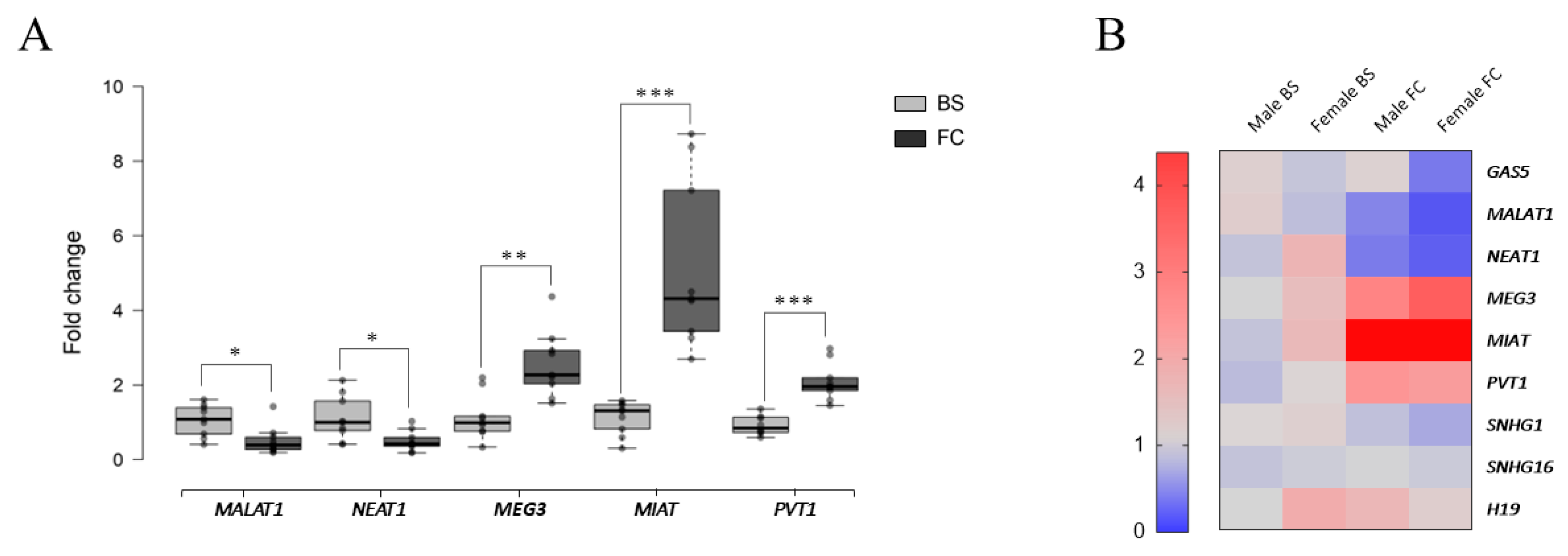

2.2. Conservation of lncRNA Expression Patterns Between Mouse and Human

2.3. Functional and Enrichment Bioinformatic Analysis of lncRNAs Across CNS Regions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human Sample Collection

4.2. Animals

4.3. Mice Sample Collection

4.4. RNA Extraction

4.5. Real-Time PCR

4.6. Functional Enrichment Study

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hangauer, M.J.; Vaughn, I.W.; McManus, M.T. Pervasive Transcription of the Human Genome Produces Thousands of Previously Unidentified Long Intergenic Noncoding RNAs. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, C.P.; Oliver, P.L.; Reik, W. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri-Robles, C.; Amador, R.; Klein, C.C.; Guigó, R.; Corominas, M.; Ruiz-Romero, M. Genomic and functional conservation of lncRNAs: Lessons from flies. Mamm. Genome 2022, 33, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, K.C.; Frith, M.C.; Mattick, J.S. Rapid evolution of noncoding RNAs: Lack of conservation does not mean lack of function. Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulitsky, I.; Shkumatava, A.; Jan, C.H.; Sive, H.; Bartel, D.P. Conserved function of lincRNAs in vertebrate embryonic development despite rapid sequence evolution. Cell 2011, 147, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policarpo, R.; Sierksma, A.; De Strooper, B.; d’Ydewalle, C. From Junk to Function: LncRNAs in CNS Health and Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14, 714768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponjavic, J.; Oliver, P.L.; Lunter, G.; Ponting, C.P. Genomic and transcriptional co-localization of protein-coding and long non-coding RNA pairs in the developing brain. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Bammann, H.; Han, D.; Xie, G. Conserved expression of lincRNA during human and macaque prefrontal cortex development and maturation. RNA 2014, 20, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.B.; Wang, P.P.; Atabay, K.D.; Murphy, E.A.; Doan, R.N.; Hecht, J.L.; Walsh, C.A. Single-cell analysis reveals transcriptional heterogeneity of neural progenitors in human cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.A.; Mattick, J.S.; Mehler, M.F. Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 2010, 1338, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Luo, T.; Zou, S.; Wu, A. The Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Central Nervous System and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.K.; Prasanth, K.V. Functional insights into the role of nuclear-retained long noncoding RNAs in gene expression control in mammalian cells. Chromosom. Res. 2013, 21, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, L.A.; Rinn, J.L. Linking RNA biology to lncRNAs. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazemzadeh, M.; Safaralizadeh, R.; Orang, A.V. LncRNAs: Emerging players in gene regulation and disease pathogenesis. J. Genet. 2015, 94, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.E.; Lim, D.A. Forging our understanding of lncRNAs in the brain. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 371, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, J.A.; Wolvetang, E.J.; Mattick, J.S.; Rinn, J.L.; Barry, G. Mechanisms of Long Non-coding RNAs in Mammalian Nervous System Development, Plasticity, Disease, and Evolution. Neuron 2015, 88, 861–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, T.R.; Qureshi, I.A.; Gokhan, S.; Dinger, M.E.; Li, G.; Mattick, J.S.; Mehler, M.F. Long noncoding RNAs in neuronal-glial fate specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. BMC Neurosci. 2010, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.D.; Diaz, A.; Nellore, A.; Delgado, R.N.; Park, K.-Y.; Gonzales-Roybal, G.; Oldham, M.C.; Song, J.S.; Lim, D.A. Integration of genome-wide approaches identifies lncRNAs of adult neural stem cells and their progeny in vivo. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D.; Zhang, B.; Tian, R.-R.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Yang, L.-M.; Cheng, C.; et al. Annotation and cluster analysis of spatiotemporal- and sex-related lncRNA expression in rhesus macaque brain. Genome Res. 2017, 27, 1608–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navandar, M.; Vennin, C.; Lutz, B.; Gerber, S. Long non-coding RNAs expression and regulation across different brain regions in primates. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakkuzha, B.M.; Liu, X.A.; McCrate, J.; Shankar, G.; Rizzo, V.; Afinogenova, A.; Young, B.; Fallahi, M.; Carvalloza, A.C.; Raveendra, B.; et al. Transcriptome analyses of adult mouse brain reveal enrichment of lncRNAs in specific brain regions and neuronal populations. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Mouse Brain Atlas. [Dataset]. 2004. Available online: https://mouse.brain-map.org/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Human Brain Atlas. [Dataset]. 2013. Available online: https://mouse.brain-map.org/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- López-Royo, T.; Moreno-Martínez, L.; Rada, G.; Macías-Redondo, S.; Calvo, A.C.; García-Redondo, A.; Manzano, R.; Osta, R. LncRNA levels in the central nervous system as novel potential players and biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Noncoding RNA Res. 2025, 14, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen Institute for Brain Science. Allen Human Brain Atlas: Microarray. RRID:SCR_007416. 2010. Available online: https://human.brain-map.org (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Wan, P.; Su, W.; Zhuo, Y. The Role of Long Noncoding RNAs in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liang, Y.; Gareev, I.; Liang, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, N.; Yang, G. LncRNA as potential biomarker and therapeutic target in glioma. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, M. New insights into long noncoding RNAs and their roles in glioma. Mol. Cancer 2018, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Kumar, S. Association of lncRNA with regulatory molecular factors in brain and their role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Metab. Brain Dis. 2021, 36, 849–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, Y.; Bai, L.; Qin, C. Long noncoding RNAs in neurodevelopment and Parkinson’s disease. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2019, 2, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishamdar, M.; Jalali, M.S.; Rashno, M. MALAT1 lncRNA and Parkinson’s Disease: The role in the Pathophysiology and Significance for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 5253–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Safari, M.; Taheri, M.; Samadian, M. Expression of Linear and Circular lncRNAs in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 72, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canseco-Rodriguez, A.; Masola, V.; Aliperti, V.; Meseguer-Beltran, M.; Donizetti, A.; Sanchez-Perez, A.M. Long Non-Coding RNAs, Extracellular Vesicles and Inflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Chen, Y. Long noncoding RNAs and Alzheimer’s disease. Clin. Interv. Aging 2016, 11, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talkowski, M.E.; Maussion, G.; Crapper, L.; Rosenfeld, J.A.; Blumenthal, I.; Hanscom, C.; Chiang, C.; Lindgren, A.; Pereira, S.; Ruderfer, D.; et al. Disruption of a large intergenic noncoding RNA in subjects with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 91, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yu, Y.; Yang, W. Long noncoding RNA and its contribution to autism spectrum disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.J.; Mirnics, K. Neurodevelopment, GABA system dysfunction, and schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2015, 40, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Mao, X.; Zhu, C.; Zou, X.; Peng, F.; Yang, W.; Li, B.; Li, G.; Ge, T.; Cui, R. GABAergic System Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 781327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuail, J.A.; Frazier, C.J.; Bizon, J.L. Molecular aspects of age-related cognitive decline: The role of GABA signaling. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouras, G.K.; Olsson, T.T.; Hansson, O. β-Amyloid peptides and amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, W.; Wei, C.; Jiang, S.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Xu, R. Pathological mechanisms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netzahualcoyotzi, C.; Tapia, R. Degeneration of spinal motor neurons by chronic AMPA-induced excitotoxicity in vivo and protection by energy substrates. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2015, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, A.J.M.; Johnsson, P.; Hagemann-Jensen, M.; Hartmanis, L.; Faridani, O.R.; Reinius, B.; Segerstolpe, Å.; Rivera, C.M.; Ren, B.; Sandberg, R. Genomic encoding of transcriptional burst kinetics. Nature 2019, 565, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oros, D.; Strunk, M.; Breton, P.; Paules, C.; Benito, R.; Moreno, E.; Garcés, M.; Godino, J.; Schoorlemmer, J. Altered gene expression in human placenta after suspected preterm labour. Placenta 2017, 55, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Ji, B.; Shen, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Huang, P.; Yu, R.; Zhang, H.; Dou, X.; Chen, Q.; et al. EVLncRNAs 3.0: An updated comprehensive database for manually curated functional long non-coding RNAs validated by low-throughput experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D98–D106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.Y. ClusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS A J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandrud, C. NetworkD3: D3 JavaScript Network Graphs from R, R Package Version 0.4.1; RStudio Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/networkD3 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

| Tissue | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Brainstem (N = 9) | Frontal Cortex (N = 9) | |

| Gender (n) | Male | 6 (66.67%) | 6 (66.67%) |

| Female | 3 (33.33%) | 3 (33.33%) | |

| Age | 58.78 ± 10.56 | 59.11 ± 10.55 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Royo, T.; Gascón, E.; Moreno-Martínez, L.; Macías-Redondo, S.; Zaragoza, P.; Manzano, R.; Osta, R. Region-Specific Expression Patterns of lncRNAs in the Central Nervous System: Cross-Species Comparison and Functional Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412069

López-Royo T, Gascón E, Moreno-Martínez L, Macías-Redondo S, Zaragoza P, Manzano R, Osta R. Region-Specific Expression Patterns of lncRNAs in the Central Nervous System: Cross-Species Comparison and Functional Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412069

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Royo, Tresa, Elisa Gascón, Laura Moreno-Martínez, Sofía Macías-Redondo, Pilar Zaragoza, Raquel Manzano, and Rosario Osta. 2025. "Region-Specific Expression Patterns of lncRNAs in the Central Nervous System: Cross-Species Comparison and Functional Insights" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412069

APA StyleLópez-Royo, T., Gascón, E., Moreno-Martínez, L., Macías-Redondo, S., Zaragoza, P., Manzano, R., & Osta, R. (2025). Region-Specific Expression Patterns of lncRNAs in the Central Nervous System: Cross-Species Comparison and Functional Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12069. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412069

_Kim.png)