A New Perspective on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis-Mediated Allergic Rhinitis: From the Mechanism of Immune Microenvironment Remodeling to Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. The Composition of Nasal Tract Microorganisms

4. Characteristics of Nasal Tract Microbial Dysbiosis in Allergic Rhinitis

4.1. Characteristics of the Nasal Tract Microbiome in Pediatric Allergic Rhinitis

4.2. Characteristics of the Nasal Tract Microbiome in Adults with Allergic Rhinitis

4.3. Regulatory Effects of Environmental and Clinical Factors on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis in Allergic Rhinitis

| Population | Sample Site | Actinobacteria | Bacteroidetes | Firmicutes | Proteobacteria | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults with AR | Middle meatus | ↑ Propionibacterium | ↑

parvimonas ↑ Staphylococcus ↑ Lactococcus ↑ Enterococcus | ↓

Ralstonia ↑ unclassified Enterobacteriaceae | [16,63] | |

| Adults with AR | Inferior turbinate | ↑

Pseudomonas ↓ Serratia ↓ Ralstonia | [64] | |||

| Adults with AR + asthma | Nasal lavage solution | ↓

Prevotella ↓ Rothia | ↑ Faecalibacterium ↑ lactobacillus ↑ clostridium_IV ↑ blautia ↑ butyricicoccus | ↑

Escherichia ↑ pelomonas | [65] | |

| Adults with AR | Nasal extracellular vesicles | ↑

Acetobacter ↓ Streptococcus | ↑

Escherichia ↑ Halomonas ↓ Zoogloea ↓ Burkholderia ↓ Pseudomonas | [43] |

5. Potential Mechanisms Linking URT Microbiome to Allergic Rhinitis

5.1. The Role of Bacteria

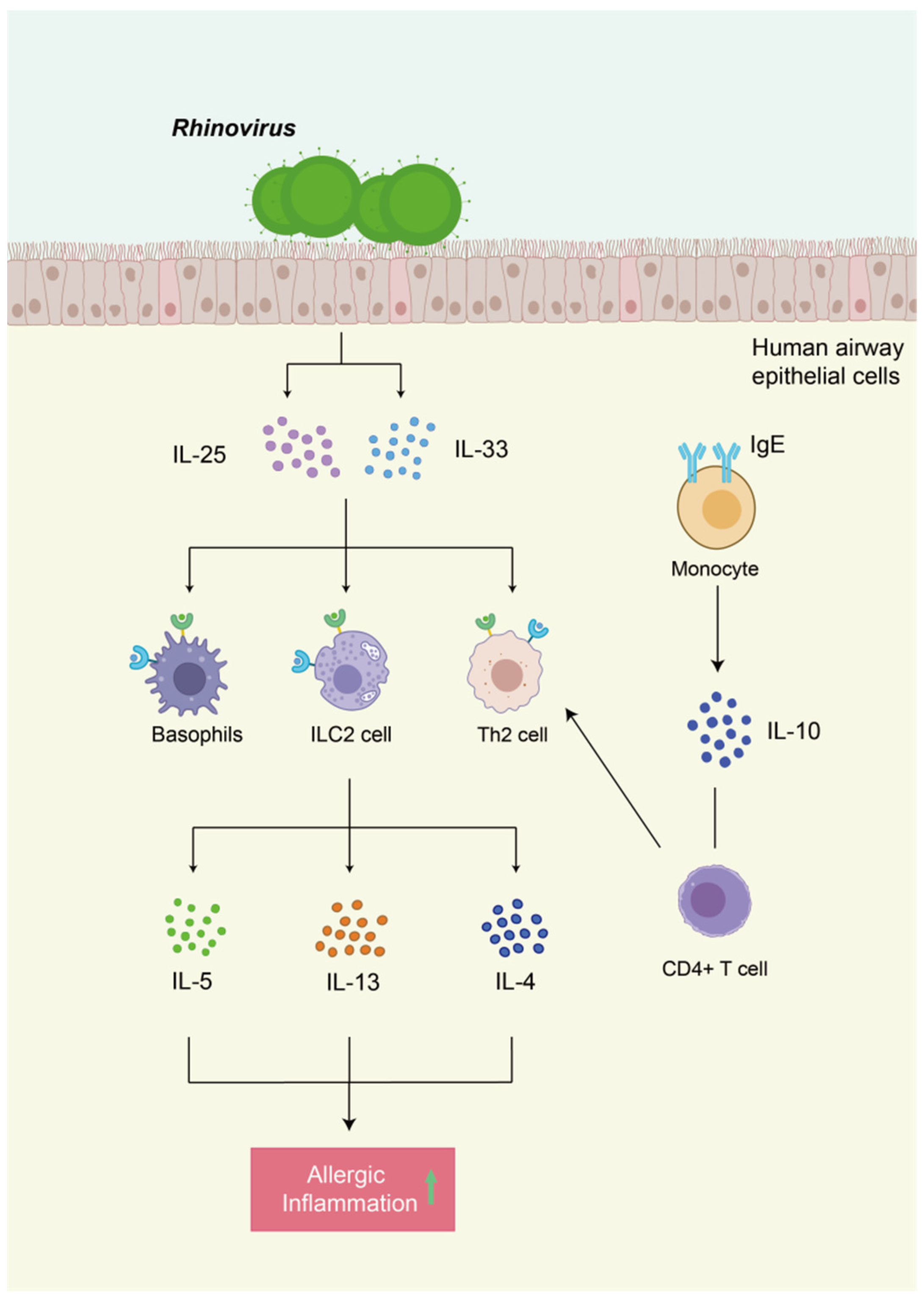

5.2. The Role of Viruses

5.3. The Roles of Other Microorganisms

5.4. The Role and Potential of the Gut-Lung Axis and Gut-Nasal Axis in Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis and Allergic Rhinitis (AR)

6. Modulation of the Nasal Microbiota May Serve as a Novel Therapeutic Approach for Allergic Rhinitis

7. Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHR | Airway Hyperresponsiveness |

| ALA | α-Linolenic Acid |

| AR | Allergic Rhinitis |

| ARC | Allergic Rhinoconjunctivitis |

| ASV | Amplicon Sequence Variant |

| CCL11 | Chemokine Eotaxin-1 |

| CFU | Colony-Forming Unit |

| CRS | Chronic Rhinosinusitis |

| DCs | Dendritic Cells |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic Acid |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FEAST | Fast Expectation-Maximization for Microbial Source Tracking |

| FFAs | Free Fatty Acids |

| GUSTO | Growing Up in Singapore toward Healthy Outcomes |

| HDM | House Dust Mites |

| HNEC | Human Nasal Epithelial Cells |

| HRV | Human Rhinovirus |

| HBD-2 | Human β-Defensin 2 |

| IAV | Influenza A Virus |

| ILC2 | Type 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells |

| LDA | Linear Discriminant Analysis |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LPC | Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| LTA | Lipoteichoic Acid |

| MC | Mast Cell |

| Mini-RQLQ | Mini Rhinoconjunctivitis Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| MRSA | Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| OTU | Operational Taxonomic Unit |

| PAR | Perennial Allergic Rhinitis |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RV | Rhinovirus |

| RSV | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| SEA | Staphylococcal Enterotoxin A |

| SEB | Staphylococcal Enterotoxin B |

| SA | Staphylococcus aureus |

| SAR | Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

| SPT | Skin Prick Test |

| TAGs | Triacylglycerols |

| Th1 | T Helper 1 Cells |

| Th2 | T Helper 2 Cells |

| TLR2 | Toll-Like Receptor 2 |

| TNSS | Total Nasal Symptom Score |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| TSLP | Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin |

| UAT | Upper Airway Tract |

References

- Greiner, A.N.; Hellings, P.W.; Rotiroti, G.; Scadding, G.K. Allergic rhinitis. Lancet 2011, 378, 2112–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, J.; Fu, Q.; He, S.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Tan, G.; Tao, Z.; Wang, D.; Wen, W.; et al. Chinese Society of Allergy Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 300–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, E.O. Allergic Rhinitis: Burden of Illness, Quality of Life, Comorbidities, and Control. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2016, 36, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stróżek, J.; Samoliński, B.K.; Kłak, A.; Gawińska-Drużba, E.; Izdebski, R.; Krzych-Fałta, E.; Raciborski, F. The indirect costs of allergic diseases. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2019, 32, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberbier, T.; Lötvall, J.; Simoens, S.; Subramanian, S.V.; Church, M.K. Economic burden of inadequate management of allergic diseases in the European Union: A GA(2) LEN review. Allergy 2014, 69, 1275–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scadding, G. Cytokine profiles in allergic rhinitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morjaria, J.B.; Caruso, M.; Emma, R.; Russo, C.; Polosa, R. Treatment of Allergic Rhinitis as a Strategy for Preventing Asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018, 18, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shi, J.; Xu, Y.; Yao, S.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. The role of the oral microbiota in allergic diseases: Current understandings and future trends. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 299, 128254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J.; Han, M.S.; Kwak, J.; Kim, T.H. Association Between Microbiota and Nasal Mucosal Diseases in terms of Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, C.J.X.; Ta, L.D.H.; Ow Yeong, Y.X.; Yap, G.C.; Chu, J.J.H.; Lee, B.W.; Tham, E.H. Role of Upper Respiratory Microbiota and Virome in Childhood Rhinitis and Wheeze: Collegium Internationale Allergologicum Update 2021. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.P. Human nasal microbiota. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R1118–R1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.T.; Frank, D.N.; Ramakrishnan, V. Microbiome of the paranasal sinuses: Update and literature review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2016, 30, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnmacht, C.; Park, J.H.; Cording, S.; Wing, J.B.; Atarashi, K.; Obata, Y.; Gaboriau-Routhiau, V.; Marques, R.; Dulauroy, S.; Fedoseeva, M.; et al. MUCOSAL IMMUNOLOGY. The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORγt⁺ T cells. Science 2015, 349, 989–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.A.; Siracusa, M.C.; Abt, M.C.; Kim, B.S.; Kobuley, D.; Kubo, M.; Kambayashi, T.; LaRosa, D.F.; Renner, E.D.; Orange, J.S.; et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cait, A.; Cardenas, E.; Dimitriu, P.A.; Amenyogbe, N.; Dai, D.; Cait, J.; Sbihi, H.; Stiemsma, L.; Subbarao, P.; Mandhane, P.J.; et al. Reduced genetic potential for butyrate fermentation in the gut microbiome of infants who develop allergic sensitization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 144, 1638–1647.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, D.; Keim, P.; Delisle, J.; Barker, B.; Rank, M.A.; Chia, N.; Schupp, J.M.; Gillece, J.D.; Cope, E.K. Mapping and comparing bacterial microbiota in the sinonasal cavity of healthy, allergic rhinitis, and chronic rhinosinusitis subjects. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2017, 7, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, A.C.; Hilário, S.; Gonçalves, M.F.M. Microbiome in Nasal Mucosa of Children and Adolescents with Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review. Children 2023, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, A.; McKennan, C.G.; Pedersen, C.T.; Stokholm, J.; Chawes, B.L.; Malby Schoos, A.M.; Naughton, K.A.; Thorsen, J.; Mortensen, M.S.; Vercelli, D.; et al. Epigenetic landscape links upper airway microbiota in infancy with allergic rhinitis at 6 years of age. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 146, 1358–1366, Correction in J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 150, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubags, N.D.J.; Marsland, B.J. Mechanistic insight into the function of the microbiome in lung diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassis, C.M.; Tang, A.L.; Young, V.B.; Pynnonen, M.A. The nasal cavity microbiota of healthy adults. Microbiome 2014, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stearns, J.C.; Davidson, C.J.; McKeon, S.; Whelan, F.J.; Fontes, M.E.; Schryvers, A.B.; Bowdish, D.M.; Kellner, J.D.; Surette, M.G. Culture and molecular-based profiles show shifts in bacterial communities of the upper respiratory tract that occur with age. ISME J. 2015, 9, 1246–1259, Erratum in ISME J. 2015, 9, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilts, M.H.; Rosas-Salazar, C.; Tovchigrechko, A.; Larkin, E.K.; Torralba, M.; Akopov, A.; Halpin, R.; Peebles, R.S.; Moore, M.L.; Anderson, L.J.; et al. Minimally Invasive Sampling Method Identifies Differences in Taxonomic Richness of Nasal Microbiomes in Young Infants Associated with Mode of Delivery. Microb. Ecol. 2016, 71, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Mihindukulasuriya, K.A.; Gao, H.; La Rosa, P.S.; Wylie, K.M.; Martin, J.C.; Kota, K.; Shannon, W.D.; Mitreva, M.; Sodergren, E.; et al. Exploration of bacterial community classes in major human habitats. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, R66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Pamp, S.J.; Fukuyama, J.; Hwang, P.H.; Cho, D.Y.; Holmes, S.; Relman, D.A. Nasal microenvironments and interspecific interactions influence nasal microbiota complexity and S. aureus carriage. Cell Host Microbe 2013, 14, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Steenhuijsen Piters, W.A.; Sanders, E.A.; Bogaert, D. The role of the local microbial ecosystem in respiratory health and disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140294. [Google Scholar]

- Man, W.H.; de Steenhuijsen Piters, W.A.; Bogaert, D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: Gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpitsch, C.; Koskinen, K.; Schöpf, V.; Moissl-Eichinger, C. The microbiome of the upper respiratory tract in health and disease. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, D.M.; Relman, D.A. The Landscape Ecology and Microbiota of the Human Nose, Mouth, and Throat. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Abu-Ali, G.; Huttenhower, C. The healthy human microbiome. Genome Med. 2016, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, E.K.; Lauber, C.L.; Hamady, M.; Fierer, N.; Gordon, J.I.; Knight, R. Bacterial community variation in human body habitats across space and time. Science 2009, 326, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazzato, M.; Zicari, A.M.; Aleandri, M.; Conte, A.L.; Longhi, C.; Vitanza, L.; Bolognino, V.; Zagaglia, C.; De Castro, G.; Brindisi, G.; et al. 16S Metagenomics Reveals Dysbiosis of Nasal Core Microbiota in Children With Chronic Nasal Inflammation: Role of Adenoid Hypertrophy and Allergic Rhinitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brindisi, G.; Marazzato, M.; Brunetti, F.; De Castro, G.; Loffredo, L.; Carnevale, R.; Cinicola, B.; Palamara, A.T.; Conte, M.P.; Zicari, A.M. Allergic rhinitis, microbiota and passive smoke in children: A pilot study. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33 (Suppl. 27), 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Feng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, Y. Microbiota Composition in Upper Respiratory Tracts of Healthy Children in Shenzhen, China, Differed with Respiratory Sites and Ages. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6515670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castranova, V.; Huffman, L.J.; Judy, D.J.; Bylander, J.E.; Lapp, L.N.; Weber, S.L.; Blackford, J.A.; Dey, R.D. Enhancement of nitric oxide production by pulmonary cells following silica exposure. Env. Health Perspect. 1998, 106 (Suppl. 5), 1165–1169. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Schenck, L.P.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M. Composition and immunological significance of the upper respiratory tract microbiota. FEBS Lett. 2016, 590, 3705–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, F.J.; Verschoor, C.P.; Stearns, J.C.; Rossi, L.; Luinstra, K.; Loeb, M.; Smieja, M.; Johnstone, J.; Surette, M.G.; Bowdish, D.M.E. The loss of topography in the microbial communities of the upper respiratory tract in the elderly. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoğlu, E.; Kalkancı, A.; Kılıç, E.; Kızıl, Y.; Aydil, U.; Diker, K.S.; Uslu, S.S. Bacterial and fungal communities in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304634. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Hauser, L.J.; Feazel, L.M.; Ir, D.; Robertson, C.E.; Frank, D.N. Sinus microbiota varies among chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes and predicts surgical outcome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 136, 334–342.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Wu, W.J.; Li, L.; Qin, H.; Li, S.N.; Zheng, G.L.; Hou, D.-M.; Huang, Q.; Cheng, L.; Jie, H.-Q.; et al. Characteristics of the microbiota in the nasopharynx and nasal cavity of healthy children before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Pediatr. 2025, 21, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Yang, F.; Meng, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Xian, J. Comparing the nasal bacterial microbiome diversity of allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis and control subjects. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 711–718. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, J.W.; Hou, J.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Leung, T.F.; Cheng, N.S.; Yam, J.C.; Kam, K.W.; Jhanji, V.; Hon, K.L. Characterization of ocular and nasopharyngeal microbiome in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 30, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.Y.; Chan, Y.L.; Tsai, Y.S.; Chen, S.A.; Wang, C.J.; Chen, K.F.; Chung, I.-F. Airway Microbial Diversity is Inversely Associated with Mite-Sensitized Rhinitis and Asthma in Early Childhood. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.Y.; Yang, Y.R.; Zhuo, M.Y.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Y.F.; Fu, C.H.; Lee, T.-J.; Chung, W.-H.; Chen, L.; Chang, C.-J. Microbiome profiling of nasal extracellular vesicles in patients with allergic rhinitis. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ta, L.D.H.; Yap, G.C.; Tay, C.J.X.; Lim, A.S.M.; Huang, C.H.; Chu, C.W.; De Sessions, P.F.; Shek, L.P.; Goh, A.; Van Bever, H.P.; et al. Establishment of the nasal microbiota in the first 18 months of life: Correlation with early-onset rhinitis and wheezing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitri-Pinheiro, S.; Soares, R.; Barata, P. The Microbiome of the Nose-Friend or Foe? Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 11, 2152656720911605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peroni, D.G.; Nuzzi, G.; Trambusti, I.; Di Cicco, M.E.; Comberiati, P. Microbiome Composition and Its Impact on the Development of Allergic Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Ren, F.; Dai, D.; Sun, N.; Qian, Y.; Song, P. The causality between intestinal flora and allergic diseases: Insights from a bi-directional two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1121273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, H.; Hermansen, M.N.; Buchvald, F.; Loland, L.; Halkjaer, L.B.; Bønnelykke, K.; Brasholt, M.; Heltberg, A.; Vissing, N.H.; Thorsen, S.V.; et al. Childhood asthma after bacterial colonization of the airway in neonates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 1487–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.M.; Mok, D.; Pham, K.; Kusel, M.; Serralha, M.; Troy, N.; Holt, B.J.; Hales, B.J.; Walker, M.L.; Hollams, E.; et al. The infant nasopharyngeal microbiome impacts severity of lower respiratory infection and risk of asthma development. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamash, D.F.; Mongodin, E.F.; White, J.R.; Voskertchian, A.; Hittle, L.; Colantuoni, E.; Milstone, A.M. The Association Between the Developing Nasal Microbiota of Hospitalized Neonates and Staphylococcus aureus Colonization. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisgaard, H.; Hermansen, M.N.; Bønnelykke, K.; Stokholm, J.; Baty, F.; Skytt, N.L.; Aniscenko, J.; Kebadze, T.; Johnston, S.L. Association of bacteria and viruses with wheezy episodes in young children: Prospective birth cohort study. BMJ 2010, 341, c4978, Correction in BMJ 2011, 343, d8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Linstow, M.L.; Schønning, K.; Hoegh, A.M.; Sevelsted, A.; Vissing, N.H.; Bisgaard, H. Neonatal airway colonization is associated with troublesome lung symptoms in infants. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 1041–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.H.F.; Lang, A.; Teo, S.M.; Judd, L.M.; Gangnon, R.; Evans, M.D.; Lee, K.E.; Vrtis, R.; Holt, P.G.; Lemanske, R.F.; et al. Developmental patterns in the nasopharyngeal microbiome during infancy are associated with asthma risk. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDade, T.W. Early environments and the ecology of inflammation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109 (Suppl. 2), 17281–17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, H.; Potaczek, D.P.; Pfefferle, P.I. The Hygiene Hypothesis and New Perspectives-Current Challenges Meeting an Old Postulate. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 637087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Guo, X.; Jiang, S.; Zuo, X.; Wang, X.; Hsu, A.C.-Y.; Qi, M.; Wang, F. Airway Microbiome and Serum Metabolomics Analysis Identify Differential Candidate Biomarkers in Allergic Rhinitis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 771136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.T.; Kim, C.M.; Ramakrishnan, V. Microbiome and disease in the upper airway. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, D.W.; Min, H.J.; Kim, M.S.; Whon, T.W.; Shin, N.R.; Kim, P.S.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kang, W.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. Dysbiosis of Inferior Turbinate Microbiota Is Associated with High Total IgE Levels in Patients with Allergic Rhinitis. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00934-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.Z.; Duan, B.Y.; Xin, F.J.; Qu, Z.H. Assessment of the bidirectional causal association between Helicobacter pylori infection and allergic diseases by mendelian randomization analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Pu, X. Regular nasal irrigation modulates nasal microbiota and improves symptoms in allergic rhinitis patients: A retrospective study. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2025, 17, 5152–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambika Manirajan, B.; Hinrichs, A.K.; Ratering, S.; Rusch, V.; Schwiertz, A.; Geissler-Plaum, R.; Eichner, G.; Cardinale, M.; Kuntz, S.; Schnell, S. Bacterial Species Associated with Highly Allergenic Plant Pollen Yield a High Level of Endotoxins and Induce Chemokine and Cytokine Release from Human A549 Cells. Inflammation 2022, 45, 2186–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, H.; Wang, Y.; Norbäck, D.; Zhao, Z.; Fu, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. Environmental impacts on childhood rhinitis: The role of green spaces, air pollutants, and indoor microbial communities in Taiyuan, a city in Northern China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Han, S.A.; Kim, W. Compositional Alterations of the Nasal Microbiome and Staphylococcus aureus-Characterized Dysbiosis in the Nasal Mucosa of Patients With Allergic Rhinitis. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 15, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Gu, S.; Fu, J. Characterization of dysbiosis of the conjunctival microbiome and nasal microbiome associated with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and allergic rhinitis. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1079154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; He, S.; Miles, P.; Li, C.; Ge, Y.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; Huang, W.; Kong, X.; Ma, S.; et al. Nasal Bacterial Microbiome Differs Between Healthy Controls and Those With Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 841995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez Ayala, A.; Hsu, C.Y.; Oles, R.E.; Matsuo, K.; Loomis, L.R.; Buzun, E.; Terrazas, M.C.; Gerner, R.R.; Lu, H.-H.; Kim, S.; et al. Commensal bacteria promote type I interferon signaling to maintain immune tolerance in mice. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20230063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, P.; Jiang, Y.; Jian, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y.; Piewngam, P.; Zheng, Y.; Cheung, G.Y.C.; Liu, Q.; Otto, M.; et al. Exacerbation of allergic rhinitis by the commensal bacterium Streptococcus salivarius. Nat. Microbiol. 2023, 8, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A. A clinical perspective of IL-1β as the gatekeeper of inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich, P.C.; Behrmann, I.; Haan, S.; Hermanns, H.M.; Müller-Newen, G.; Schaper, F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem. J. 2003, 374 Pt 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdis, M.; Aab, A.; Altunbulakli, C.; Azkur, K.; Costa, R.A.; Crameri, R.; Duan, S.; Eiwegger, T.; Eljaszewicz, A.; Ferstl, R.; et al. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor β, and TNF-α: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 984–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Dong, C. IL-25 in allergic inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 278, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, M.F.; Postigo, I.; Tomaz, C.T.; Martínez, J. Alternaria alternata allergens: Markers of exposure, phylogeny and risk of fungi-induced respiratory allergy. Environ. Int. 2016, 89–90, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, J.M.; Oh, B.M.; Kim, J.Y.; Jung, H.J.; Kim, B.S.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, D.W. Potential Immunoinflammatory Role of Staphylococcal Enterotoxin A in Atopic Dermatitis: Immunohistopathological Analysis and in vitro Assay. Ann. Dermatol. 2013, 25, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandron, M.; Ariès, M.F.; Brehm, R.D.; Tranter, H.S.; Acharya, K.R.; Charveron, M.; Davrinche, C. Human dendritic cells conditioned with Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B promote TH2 cell polarization. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 117, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Gao, J.; Ji, W. Patho-immunological mechanisms of atopic dermatitis: The role of the three major human microbiomes. Scand. J. Immunol. 2024, 100, e13403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorski, S.A.; Hahn, Y.S.; Braciale, T.J. Group 2 innate lymphoid cell production of IL-5 is regulated by NKT cells during influenza virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitkauskiene, B.; Johansson, A.K.; Sergejeva, S.; Lundin, S.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lötvall, J. Regulation of bone marrow and airway CD34+ eosinophils by interleukin-5. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004, 30, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. IL-13 effector functions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 21, 425–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, N.; Zheng, X.; Liu, J.; Che, Y.; Wang, J. Altered Nasal Microbiota-Metabolome Interactions in Allergic Rhinitis: Implications for Inflammatory Dysregulation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 9919–9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; van Putten, J.P.M.; Wösten, M. Biological functions of bacterial lysophospholipids. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2023, 82, 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- de Steenhuijsen Piters, W.A.; Bogaert, D. Unraveling the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Nasopharyngeal Bacterial Community Structure. mBio 2016, 7, e00009–e00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menberu, M.A.; Cooksley, C.; Ramezanpour, M.; Bouras, G.; Wormald, P.J.; Psaltis, A.J.; Vreugde, S. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of probiotic properties of Corynebacterium accolens isolated from the human nasal cavity. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 255, 126927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.L.; Marzahn, M.R.; Valdespino, E.L.; Patel, R.; Cole, A.M. Nasal microbiome inhabitants with anti-Staphylococcus aureus activity. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanders, R.L.; Gomez, H.M.; Hsu, A.C.; Daly, K.; Wark, P.A.B.; Horvat, J.C.; Hansbro, P.M. Inflammatory and antiviral responses to influenza A virus infection are dysregulated in pregnant mice with allergic airway disease. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2023, 325, L385–L398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, M.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Mao, Y.; Ma, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Guo, L. Characteristics of upper respiratory tract rhinovirus in children with allergic rhinitis and its role in disease severity. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0385323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, S.; Calvo, C.; Pozo, F.; Casas, I.; García-García, M.L. Lung function, allergic sensitization and asthma in school-aged children after viral-coinfection bronchiolitis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, J.; Jayaraman, A.; Jackson, D.J.; Macintyre, J.D.R.; Edwards, M.R.; Walton, R.P.; Zhu, J.; Ching, Y.M.; Shamji, B.; Edwards, M.; et al. Rhinovirus-induced IL-25 in asthma exacerbation drives type 2 immunity and allergic pulmonary inflammation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 256ra134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, R.K.; Pyle, D.M.; Farrar, J.D.; Gill, M.A. IgE-mediated regulation of IL-10 and type I IFN enhances rhinovirus-induced Th2 differentiation by primary human monocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2020, 50, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ahmad, M.; Jusufovic, E.; Arifhodzic, N.; Rodriguez, T.; Nurkic, J. Association of molds and metrological parameters to frequency of severe asthma exacerbation. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2019, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, V.P.; Shen, H.D.; Banerjee, B. Respiratory fungal allergy. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Rojas, I.G.; Edgerton, M. Candida albicans Sap6 Initiates Oral Mucosal Inflammation via the Protease Activated Receptor PAR2. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 912748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, S.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Lin, X.; Chen, C.; Lin, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. Fecal and serum metabolomic signatures and gut microbiota characteristics of allergic rhinitis mice model. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1150043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsland, B.J.; Trompette, A.; Gollwitzer, E.S. The Gut-Lung Axis in Respiratory Disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2015, 12 (Suppl. 2), S150–S156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieërs, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Khoury, G.; Hajjar, C.; Geitani, R.; Karam Sarkis, D.; Butel, M.J.; Barbut, F.; Abifadel, M.; Kapel, N. Gut microbiota and viral respiratory infections: Microbial alterations, immune modulation, and impact on disease severity: A narrative review. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1605143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, A.M.; West, N.P.; Zhang, P.; Smith, P.K.; Cripps, A.W.; Cox, A.J. The Gut Microbiome of Adults with Allergic Rhinitis Is Characterised by Reduced Diversity and an Altered Abundance of Key Microbial Taxa Compared to Controls. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.S.; Zhang, B.; Gao, Z.L.; Zheng, R.P.; Marcellin, D.; Saro, A.; Pan, J.; Chu, L.; Wang, T.S.; Huang, J.F. Altered diversity and composition of gut microbiota in patients with allergic rhinitis. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 161 Pt A, 105272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Tanaka, K.; Ohya, Y.; Miyamoto, S.; Matsunaga, I.; Yoshida, T.; Hirota, Y.; Oda, H. Fish and fat intake and prevalence of allergic rhinitis in Japanese females: The Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, J.C.; Koestler, D.C.; Stanton, B.A.; Davidson, L.; Moulton, L.A.; Housman, M.L.; Moore, J.H.; Guill, M.F.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L.; et al. Serial analysis of the gut and respiratory microbiome in cystic fibrosis in infancy: Interaction between intestinal and respiratory tracts and impact of nutritional exposures. mBio 2012, 3, e00251-00212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Singer, B.H.; Newstead, M.W.; Falkowski, N.R.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Standiford, T.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. Enrichment of the lung microbiome with gut bacteria in sepsis and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, O. Various effects of different probiotic strains in allergic disorders: An update from laboratory and clinical data. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 160, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wise, S.K.; Lin, S.Y.; Toskala, E.; Orlandi, R.R.; Akdis, C.A.; Alt, J.A.; Azar, A.; Baroody, F.M.; Bachert, C.; Canonica, G.W.; et al. International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Allergic Rhinitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 108–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårtensson, A.; Nordström, F.U.; Cervin-Hoberg, C.; Lindstedt, M.; Sakellariou, C.; Cervin, A.; Greiff, L. Nasal administration of a probiotic assemblage in allergic rhinitis: A randomised placebo-controlled crossover trial. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2022, 52, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellaton, C.; Nutten, S.; Thierry, A.C.; Boudousquié, C.; Barbier, N.; Blanchard, C.; Corthésy, B.; Mercenier, A.; Spertini, F. Intragastric and Intranasal Administration of Lactobacillus paracasei NCC2461 Modulates Allergic Airway Inflammation in Mice. Int. J. Inflam. 2012, 2012, 686739. [Google Scholar]

- Spacova, I.; Petrova, M.I.; Fremau, A.; Pollaris, L.; Vanoirbeek, J.; Ceuppens, J.L.; Seys, S.; Lebeer, S. Intranasal administration of probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG prevents birch pollen-induced allergic asthma in a murine model. Allergy 2019, 74, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożek-Mądry, E.; Ziuzia-Januszewska, L.; Misztal, O.; Burska, Z.; Sosnowska-Turek, E.; Sierdziński, J. Nasal Rinsing with Probiotics-Microbiome Evaluation in Patients with Inflammatory Diseases of the Nasal Mucosa. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Peng, S.; Li, M.; Ao, X.; Liu, Z. The Efficacy and Safety of Probiotics for Allergic Rhinitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 848279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghi, O.; Dumitru, M.; Cergan, R.; Musat, G.; Serboiu, C.; Vrinceanu, D. Local Allergic Rhinitis-A Challenge for Allergology and Otorhinolaryngology Cooperation (Scoping Review). Life 2024, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, P.; Canonica, G.W. Local Allergic Rhinitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2024, 12, 1430–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, A.T.; Edwards, H.A. Review of probiotic use in otolaryngology. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lue, K.H.; Sun, H.L.; Lu, K.H.; Ku, M.S.; Sheu, J.N.; Chan, C.H.; Wang, Y.-H. A trial of adding Lactobacillus johnsonii EM1 to levocetirizine for treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis in children aged 7-12 years. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2012, 76, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Li, A.; Yu, L.; Qin, G. The role of probiotics in prevention and treatment for patients with allergic rhinitis: A systematic review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2015, 29, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.F.; Lin, H.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Hsu, C.H. Treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis with lactic acid bacteria. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2004, 15, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.C.; Hsu, C.H. The efficacy and safety of heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei for treatment of perennial allergic rhinitis induced by house-dust mite. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2005, 16, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Healthy Population | Sampling Site and Collection Method | Identification Techniques | Detected Bacteria | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants | Anterior nares, Nasal swab | 16S rDNA gene sequencing | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Dolosigranulum, Moraxella | [33] |

| Nasopharynx, Nasopharyngeal swab | 16S rDNA gene sequencing | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Staphylococcus, Faecalibacterium, Streptococcus, Moraxella | [33] | |

| Oropharynx, Oropharyngeal swab | 16S rDNA gene sequencing | Prevotella, Streptococcus, Vaillonella, Haemophilus, Moraxella, Neisseria | [33] | |

| Adults | Anterior nares, Nasal swab | 16S rDNA pyrosequencing; bacterial culture | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Prevotella, Dolosigranulum, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Moraxella, Escherichia shigella | [24] |

| Middle meatus, Middle meatus swab | 16S rDNA pyrosequencing; bacterial culture; 16S rRNA and ITS next-generation sequencing | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Prevotella, Dolosigranulum, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Moraxella, Escherichia shigella | [24,37] | |

| Sinus swab | 16S rDNA gene sequencing | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Prevotella, Staphylococcus, Anaerococcus, Peptoniphilus, Ralstonia | [34,38] | |

| Nasopharynx, Nasopharyngeal swab | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, Sphingobacterium, Staphylococcus, Faecalibacterium, Streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Haemophilus | [35] | |

| Oropharynx, Oropharyngeal swab | 16S rRNA pyrosequencing; bacterial culture | Corynebacterium, Rothia, Prevotella, Porphyromonas, Streptococcus, Vaillonella, Haemophilus, Moraxella | [35] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, L.; Cheng, X.; Liu, B.; Hao, Y.; Long, Z.; Hu, Q.; Huo, B.; Xie, T.; Cheng, Q.; Zhou, Y.; et al. A New Perspective on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis-Mediated Allergic Rhinitis: From the Mechanism of Immune Microenvironment Remodeling to Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412061

Du L, Cheng X, Liu B, Hao Y, Long Z, Hu Q, Huo B, Xie T, Cheng Q, Zhou Y, et al. A New Perspective on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis-Mediated Allergic Rhinitis: From the Mechanism of Immune Microenvironment Remodeling to Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412061

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Lijun, Xiangning Cheng, Bo Liu, Yuzhe Hao, Ziyi Long, Qianxue Hu, Bingyue Huo, Tianjian Xie, Qing Cheng, Yue Zhou, and et al. 2025. "A New Perspective on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis-Mediated Allergic Rhinitis: From the Mechanism of Immune Microenvironment Remodeling to Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412061

APA StyleDu, L., Cheng, X., Liu, B., Hao, Y., Long, Z., Hu, Q., Huo, B., Xie, T., Cheng, Q., Zhou, Y., & Chen, J. (2025). A New Perspective on Nasal Microbiota Dysbiosis-Mediated Allergic Rhinitis: From the Mechanism of Immune Microenvironment Remodeling to Microbiota-Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12061. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412061