Cross-Study Meta-Analysis of Blood Transcriptomes in Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

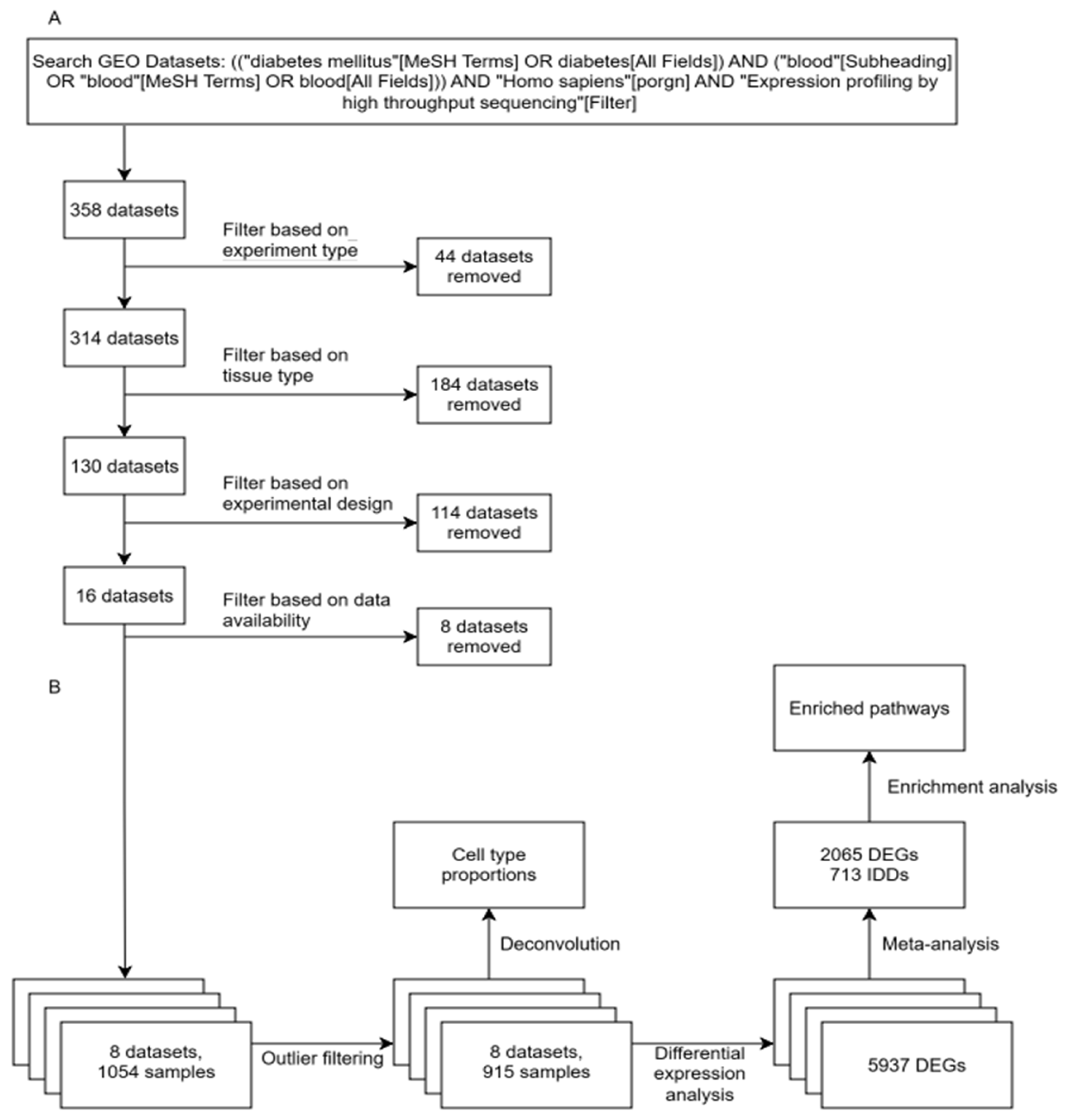

2.1. Differential Expression Analysis Across Cohorts

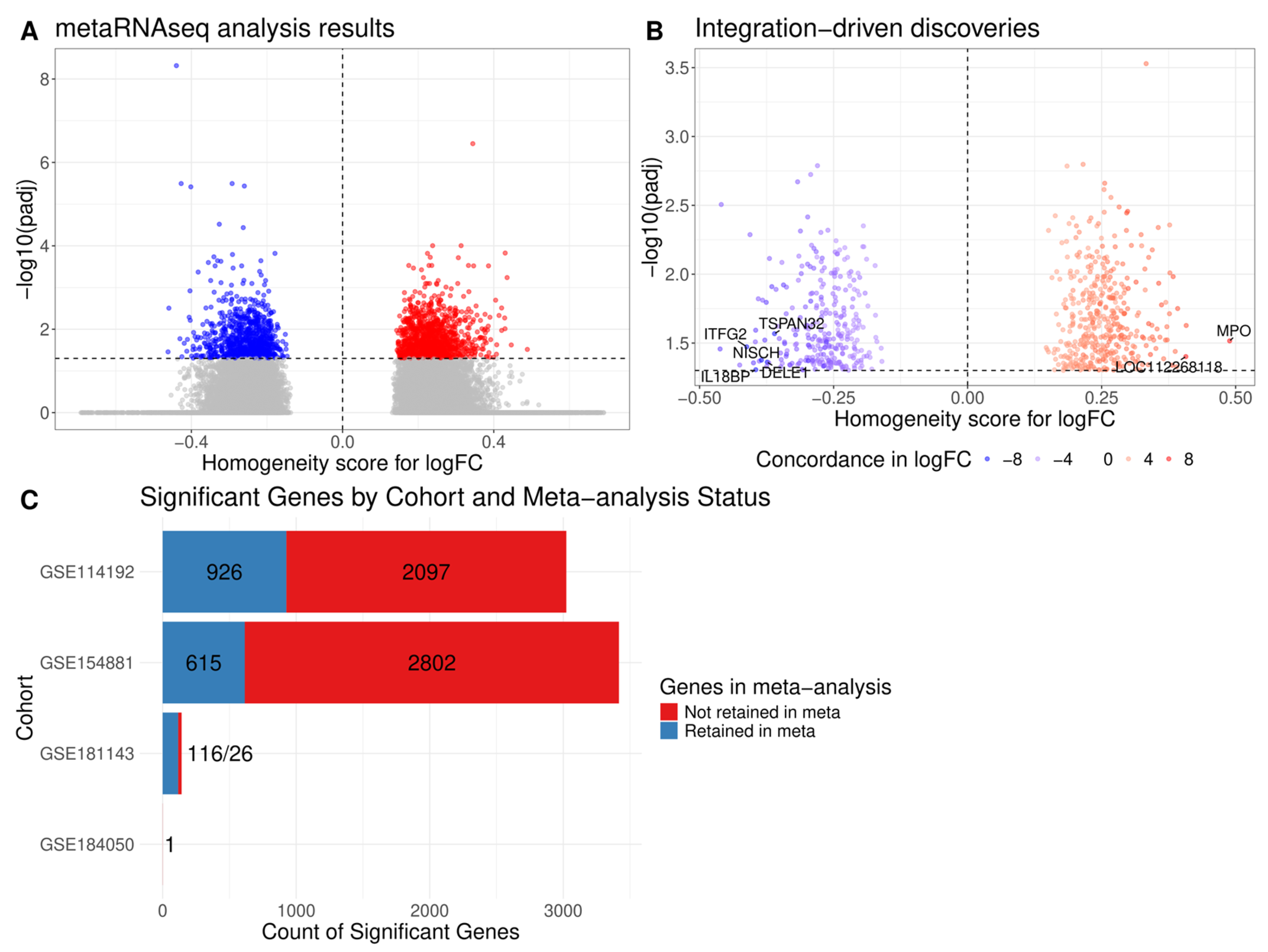

2.2. Meta-Analysis of Differential Expression Analysis Results

2.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Cohorts and Participants

4.2. Blood Sample Collection

4.3. Total RNA Isolation

4.4. RNA-Seq Library Preparation

4.5. Sequencing

4.6. Gene Expression Omnibus Datasets

4.7. Bulk RNA-Seq Data Analysis

4.8. Data Availability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| DEG | Differentially expressed gene |

| IDD | Integration-driven discovery |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| ERAD | Endoplasmic-reticulum-associated protein degradation |

| FBG | Fasting blood glucose |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| HCA | Hierarchical cluster analysis |

| CCC | Cophenetic correlation coefficient |

References

- Worldwide trends in diabetes since 1980: A pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet 2016, 387, 1513–1530. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.L.; Pavkov, M.E.; Magliano, D.J.; Shaw, J.E.; Gregg, E.W. Global trends in diabetes complications: A review of current evidence. Diabetologia 2019, 62, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.-H.; Petty, L.E.; North, K.E.; McCormick, J.B.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Gamazon, E.R.; Below, J.E. Novel Diabetes Gene Discovery through Comprehensive Characterization and Integrative Analysis of Longitudinal Gene Expression Changes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 31, 3191–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.-Y.; Chen, S.-L.; Qin, X.-R.; Lin, S.-L.; Xu, Y.; Lu, L.-N.; Zou, H.-D. Changes and Related Factors of Blood CCN1 Levels in Diabetic Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1131993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Z.; Chen, Y.-M.; Gong, W.-K.; Lai, J.-B.; Yao, B.-B.; Zhao, Z.-J.; Lu, Q.-K.; Ye, K.; Ji, L.-D.; Xu, J. Shared and Specific Biological Signalling Pathways for Diabetic Retinopathy, Peripheral Neuropathy and Nephropathy by High-Throughput Sequencing Analysis. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2022, 19, 14791641221122918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinhaes, C.L.; Fukutani, E.R.; Santana, G.C.; Arriaga, M.B.; Barreto-Duarte, B.; Araújo-Pereira, M.; Maggitti-Bezerril, M.; Andrade, A.M.S.; Figueiredo, M.C.; Milne, G.L.; et al. An Integrative Multi-Omics Approach to Characterize Interactions between Tuberculosis and Diabetes Mellitus. iScience 2024, 27, 109135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckold, C.; Kumar, V.; Weiner, J.; Alisjahbana, B.; Riza, A.-L.; Ronacher, K.; Coronel, J.; Kerry-Barnard, S.; Malherbe, S.T.; Kleynhans, L.; et al. Impact of Intermediate Hyperglycemia and Diabetes on Immune Dysfunction in Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Lim, J.; Han, K.Y.; Seo, I.-H.; Jee, J.H.; Cho, S.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Choi, S.C.; Koh, J.H.; Lee, J.-Y.; et al. Single-Cell Analysis of Human PBMCs in Healthy and Type 2 Diabetes Populations: Dysregulated Immune Networks in Type 2 Diabetes Unveiled through Single-Cell Profiling. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1397661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, N.P.; Song, J.; Nita-Lazar, A. EnsMOD: A Software Program for Omics Sample Outlier Detection. J. Comput. Biol. 2023, 30, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glotov, A.S.; Zelenkova, I.E.; Vashukova, E.S.; Shuvalova, A.R.; Zolotareva, A.D.; Polev, D.E.; Barbitoff, Y.A.; Glotov, O.S.; Sarana, A.M.; Shcherbak, S.G.; et al. RNA Sequencing of Whole Blood Defines the Signature of High Intensity Exercise at Altitude in Elite Speed Skaters. Genes 2022, 13, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quach, H.Q.; Goergen, K.M.; Grill, D.E.; Haralambieva, I.H.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Poland, G.A.; Kennedy, R.B. Virus-Specific and Shared Gene Expression Signatures in Immune Cells after Vaccination in Response to Influenza and Vaccinia Stimulation. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1168784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, H.; Shannon, C.P.; Fishbane, N.; Ruan, J.; Zhou, M.; Balshaw, R.; Wilson-McManus, J.E.; Ng, R.T.; McManus, B.M.; Tebbutt, S.J. Variation in RNA-Seq Transcriptome Profiles of Peripheral Whole Blood from Healthy Individuals with and without Globin Depletion. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheerin, D.; Lakay, F.; Esmail, H.; Kinnear, C.; Sansom, B.; Glanzmann, B.; Wilkinson, R.J.; Ritchie, M.E.; Coussens, A.K. Identification and Control for the Effects of Bioinformatic Globin Depletion on Human RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelking, L.R. Chapter 37—Gluconeogenesis. In Textbook of Veterinary Physiological Chemistry; Third, E., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 225–230. ISBN 978-0-12-391909-0. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, M.J.; Longacre, M.J.; Langberg, E.-C.; Tibell, A.; Kendrick, M.A.; Fukao, T.; Ostenson, C.-G. Decreased Levels of Metabolic Enzymes in Pancreatic Islets of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 1087–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Liu, Y.Q. Reduction of Islet Pyruvate Carboxylase Activity Might Be Related to the Development of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Agouti-K Mice. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 204, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, K.K.Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, J.-K.; Wang, B.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Hallenborg, P.; Hoo, R.L.C.; Lam, K.S.L.; et al. The MDM2-P53-Pyruvate Carboxylase Signalling Axis Couples Mitochondrial Metabolism to Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Pancreatic β-Cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; Dong, H.; Lin, H.; Ho, M.Y.; Hu, K.; Zhang, N.; Ma, J.; Xie, R.; Cheng, K.K.; et al. The Mitochondrial Enzyme Pyruvate Carboxylase Restricts Pancreatic β-Cell Senescence by Blocking P53 Activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401218121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, X. Pyruvate Carboxylase as a Moonlighting Metabolic Enzyme Protects β-Cell From Senescence. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, J.; Long, Y.S.; Epstein, P.N.; Liu, Y.Q. The Role of Pyruvate Carboxylase in Insulin Secretion and Proliferation in Rat Pancreatic Beta Cells. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.M.; Longacre, M.J.; Stoker, S.W.; Boonsaen, T.; Jitrapakdee, S.; Kendrick, M.A.; Wallace, J.C.; MacDonald, M.J. Impaired Anaplerosis and Insulin Secretion in Insulinoma Cells Caused by Small Interfering RNA-Mediated Suppression of Pyruvate Carboxylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 28048–28059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Han, J.; Epstein, P.N.; Long, Y.S. Enhanced Rat Beta-Cell Proliferation in 60% Pancreatectomized Islets by Increased Glucose Metabolic Flux through Pyruvate Carboxylase Pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 288, E471–E478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, A.; Alvarez-Perez, J.C.; Avizonis, D.; Kin, T.; Ficarro, S.B.; Choi, D.W.; Karakose, E.; Badur, M.G.; Evans, L.; Rosselot, C.; et al. Glucose-Dependent Partitioning of Arginine to the Urea Cycle Protects β-Cells from Inflammation. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 432–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, A.; van Rooyen, L.; Evans, L.; Armstrong, N.; Avizonis, D.; Kin, T.; Bird, G.H.; Reddy, A.; Chouchani, E.T.; Liesa-Roig, M.; et al. Glucose Metabolism and Pyruvate Carboxylase Enhance Glutathione Synthesis and Restrict Oxidative Stress in Pancreatic Islets. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 110037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Sabet, S.; El-Ghor, A.A.; Kamel, N.; Anis, S.E.; Morris, J.S.; Stein, T. Fibulin-2 Is Required for Basement Membrane Integrity of Mammary Epithelium. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhang, F.; Gu, W.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X. FBLN2 Is Associated with Goldenhar Syndrome and Is Essential for Cranial Neural Crest Cell Development. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1537, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WalyEldeen, A.A.; Sabet, S.; Anis, S.E.; Stein, T.; Ibrahim, A.M. FBLN2 Is Associated with Basal Cell Markers Krt14 and ITGB1 in Mouse Mammary Epithelial Cells and Has a Preferential Expression in Molecular Subtypes of Human Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 208, 673–686, Correction in Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 208, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Nenkov, M.; Schröder, D.C.; Abubrig, M.; Gassler, N.; Chen, Y. Fibulin 2 Is Hypermethylated and Suppresses Tumor Cell Proliferation through Inhibition of Cell Adhesion and Extracellular Matrix Genes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Duan, M.; He, J.; Halizere, S.; Chen, N.; Chen, X.; Jiao, Y.; He, W.; Dyar, K.A.; et al. Multi-Omics Reveals Different Signatures of Obesity-Prone and Obesity-Resistant Mice. iMetaOmics 2025, 2, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; Goda, T.; Mochizuki, K. In Vivo Evidence of Enhanced Di-Methylation of Histone H3 K4 on Upregulated Genes in Adipose Tissue of Diabetic Db/Db Mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 404, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasinska, M.A.; Drzewoski, J.; Sliwinska, A. Epigenetic Modifications in Adipose Tissue—Relation to Obesity and Diabetes. Arch. Med. Sci. 2016, 12, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Dong, X.-P.; Samie, M.; Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Goschka, A.; Shen, D.; Zhou, Y.; Harlow, J.; et al. TPC Proteins Are Phosphoinositide- Activated Sodium-Selective Ion Channels in Endosomes and Lysosomes. Cell 2012, 151, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arredouani, A.; Ruas, M.; Collins, S.C.; Parkesh, R.; Clough, F.; Pillinger, T.; Coltart, G.; Rietdorf, K.; Royle, A.; Johnson, P.; et al. Nicotinic Acid Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NAADP) and Endolysosomal Two-Pore Channels Modulate Membrane Excitability and Stimulus-Secretion Coupling in Mouse Pancreatic β Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 21376–21392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cane, M.C.; Parrington, J.; Rorsman, P.; Galione, A.; Rutter, G.A. The Two Pore Channel TPC2 Is Dispensable in Pancreatic β-Cells for Normal Ca2+ Dynamics and Insulin Secretion. Cell Calcium 2016, 59, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lear, P.V.; González-Touceda, D.; Porteiro Couto, B.; Viaño, P.; Guymer, V.; Remzova, E.; Tunn, R.; Chalasani, A.; García-Caballero, T.; Hargreaves, I.P.; et al. Absence of Intracellular Ion Channels TPC1 and TPC2 Leads to Mature-Onset Obesity in Male Mice, Due to Impaired Lipid Availability for Thermogenesis in Brown Adipose Tissue. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, L.D.; Farrell, C.; Hale, C.; Rubbi, L.; Rinaldi, A.; Civelek, M.; Pan, C.; Lam, L.; Montoya, D.; Edillor, C.; et al. Epigenome-Wide Association in Adipose Tissue from the METSIM Cohort. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1830–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaar, A.; Sun, Y.; Sukumaran, P.; Rosenberger, T.A.; Krout, D.; Roemmich, J.N.; Brinbaumer, L.; Claycombe-Larson, K.; Singh, B.B. Ca(2+) Entry via TRPC1 Is Essential for Cellular Differentiation and Modulates Secretion via the SNARE Complex. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs231878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, M.; Kim, E. The Shank Family of Scaffold Proteins. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113 Pt 11, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeisser, M.J.; Verpelli, C. Chapter 10—SHANK Mutations in Intellectual Disability and Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Neuronal and Synaptic Dysfunction in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Intellectual Disability; Sala, C., Verpelli, C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 151–160. ISBN 978-0-12-800109-7. [Google Scholar]

- May, H.J.; Jeong, J.; Revah-Politi, A.; Cohen, J.S.; Chassevent, A.; Baptista, J.; Baugh, E.H.; Bier, L.; Bottani, A.; Carminho, A.; et al. Truncating Variants in the SHANK1 Gene Are Associated with a Spectrum of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 1912–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltau, M.; Richter, D.; Kreienkamp, H.-J. The Insulin Receptor Substrate IRSp53 Links Postsynaptic Shank1 to the Small G-Protein Cdc42. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2002, 21, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, F.; Gong, Y.; Lippa, C.F. The Potential Role of Insulin on the Shank-Postsynaptic Platform in Neurodegenerative Diseases Involving Cognition. Am. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Other Dement. 2014, 29, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossa, A.; Pagano, J.; Ponzoni, L.; Tozzi, A.; Vezzoli, E.; Sciaccaluga, M.; Costa, C.; Beretta, S.; Francolini, M.; Sala, M.; et al. Developmental Impaired Akt Signaling in the Shank1 and Shank3 Double Knock-out Mice. Mol. Psychiatry 2021, 26, 1928–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. The PI3K/AKT Pathway in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1483–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Peng, L.; Huang, D.; Gavin, A.; Luan, F.; Tran, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, X.; Matteson, J.; Wilson, I.A.; et al. Structural and Mechanistic Insights into Disease-Associated Endolysosomal Exonucleases PLD3 and PLD4. Structure 2024, 32, 766–779.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claire Lee, J.; Shirey, R.J.; Turner, L.D.; Park, H.; Lairson, L.L.; Janda, K.D. Discovery of PLD4 Modulators by High-Throughput Screening and Kinetic Analysis. Results Chem. 2024, 7, 101349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalamandris, S.; Antonopoulos, A.S.; Oikonomou, E.; Papamikroulis, G.-A.; Vogiatzi, G.; Papaioannou, S.; Deftereos, S.; Tousoulis, D. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetes: Current Concepts and Future Perspectives. Eur. Cardiol. 2019, 14, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xing, K.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Ding, X. Using Machine Learning to Identify Biomarkers Affecting Fat Deposition in Pigs by Integrating Multisource Transcriptome Information. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 10359–10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovenzana, A.; Carnovale, D.; Phillips, B.; Petrelli, A.; Giannoukakis, N. Neutrophils and Their Role in the Aetiopathogenesis of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. Metab. Res. Rev. 2022, 38, e3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Deng, K.-Y.; Singh, R.; Tian, Q.; Gong, Y.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Q.; Boisclair, Y.R.; et al. Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation (ERAD) Has a Critical Role in Supporting Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion in Pancreatic β-Cells. Diabetes 2019, 68, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, N.; Liu, T.; Ji, Y.; Reinert, R.B.; Torres, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, M.; Tang, C.-H.A.; Hu, C.-C.A.; Liu, C.; et al. Sel1L-Hrd1 ER-Associated Degradation Maintains β Cell Identity via TGF-β Signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 3499–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Kim, G.H.; Pan, L.; Qi, L. Regulation of Leptin Signaling and Diet-Induced Obesity by SEL1L-HRD1 ER-Associated Degradation in POMC Expressing Neurons. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, U.; Cao, Q.; Yilmaz, E.; Lee, A.-H.; Iwakoshi, N.N.; Ozdelen, E.; Tuncman, G.; Görgün, C.; Glimcher, L.H.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Links Obesity, Insulin Action, and Type 2 Diabetes. Science 2004, 306, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z.; Bhatt, K.; Oh, H.J.; Lanting, L.; Deshpande, S.; Jia, Y.; Lai, J.Y.C.; O’Connor, C.L.; et al. An Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Regulated LncRNA Hosting a MicroRNA Megacluster Induces Early Features of Diabetic Nephropathy. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, M.; Kato, M.; Lanting, L.; Wang, M.; Tunduguru, R.; Natarajan, R. Role of MiR-379 in High-Fat Diet-Induced Kidney Injury and Dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2022, 323, F686–F699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Ji, Y.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, C.; Sun, Q.; Lei, S. Identification and Validation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Diagnostic Biomarkers for Type 1 Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Based on Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1478139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveros-Mckay, F.; Roberts, D.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Yu, B.; Soranzo, N.; Danesh, J.; Selvin, E.; Butterworth, A.S.; Barroso, I. An Expanded Genome-Wide Association Study of Fructosamine Levels Identifies RCN3 as a Replicating Locus and Implicates FCGRT as the Effector Transcript. Diabetes 2022, 71, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Bukhari, S.A.; Ali, M.; Lee, H.-W. Upstream Signalling of MTORC1 and Its Hyperactivation in Type 2 Diabetes (T2D). BMB Rep. 2017, 50, 601–609, Correction in BMB Rep. 2018, 51, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, P.; Qin, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Sun, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Multi-Omic Insight into the Causal Networks of Arsenic-Related Genes in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 305, 119195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virginia, D.M.; Dwiprahasto, I.; Wahyuningsih, M.S.H.; Nugrahaningsih, D.A.A. The Effect of PRKAA2 Variation on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in the Asian Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 29, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razooqi, O.A.; Ghazi, H.F.; Khudair, M.S. Evaluation of Serum IL 18/IL 18 Binding Protein Ratio and Their Relation with IL- 18 Gene Polymorphisms in Sample of Iraqi Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. A Case Control Study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2024, 74, S181–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y. Biomarker Signatures Distinguish Diabetic Retinopathy and Diabetic Nephropathy. Diabetol. Int. 2025, 16, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Cao, Y.; Hao, J.; Yu, Y.; Lu, W.; Guo, T.; Yuan, S. Investigation and Validation of Genes Associated with Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Diabetic Retinopathy Using Various Machine Learning Algorithms. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 254, 110317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsay, A.; Wang, J.-C. The Role of PIK3R1 in Metabolic Function and Insulin Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Miura, A.; Abu Saleh, M.M.; Shimizu, K.; Mita, Y.; Tanida, R.; Hirako, S.; Shioda, S.; Gmyr, V.; Kerr-Conte, J.; et al. The NERP-4-SNAT2 Axis Regulates Pancreatic β-Cell Maintenance and Function. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, K.; Fairweather, S.J. Amino Acid Transporters in the Regulation of Insulin Secretion and Signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozzi, F.; Eizirik, D.L. ER Stress and the Decline and Fall of Pancreatic Beta Cells in Type 1 Diabetes. Ups. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 121, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Luo, J.; Xie, H. High Glucose-Induced Alternative Splicing of MEF2D in Macrophages Promotes Vascular Chronic Inflammation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Mediating M1 Macrophage Polarization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 758, 151657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, E.; De Vas, M.G.; Balboa, D.; Cuenca-Ardura, M.; Bonàs-Guarch, S.; Planas-Fèlix, M.; Mollandin, F.; Torrens-Dinarès, M.; Maestro, M.A.; García-Hurtado, J.; et al. HNF1A and A1CF Coordinate a Beta Cell Transcription-Splicing Axis That Is Disrupted in Type 2 Diabetes. Cell Metab. 2025, 37, 1870–1889.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Kim, N.H.; Kwon, M.; Park, J.; Lim, D.; Kim, Y.; Gil, W.; Cheong, Y.H.; Park, S.-A. The Inhibitory Effect of Gremlin-2 on Adipogenesis Suppresses Breast Cancer Cell Growth and Metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2023, 25, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Chen, Y.; Gu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Luo, Y.; et al. Association Between Circulating Gremlin 2 and β-Cell Function Among Participants With Prediabetes and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes 2025, 17, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Kumar, V.; Mishra, A.; Song, S.; Aslam, R.; Hussain, A.; Wang, H.; Zhou, X.; He, X.; Wu, G.; et al. Grem2 Mediates Podocyte Apoptosis in High Glucose Milieu. Biochimie 2019, 160, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, M.S.; Yun, J.-Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, M.-O.; Go, S.-H.; Jin, H.J.; Koh, E.H. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Mediated Suppression of GREM2 Inhibits Renal Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Attenuates the Progression of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Stem Cells 2025, 18, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Tang, S.-G.; Yuan, Z.-M. Gremlin 2 Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation through Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5891–5896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Li, D.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, N.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, S.; et al. GREM2 Is Associated with Human Central Obesity and Inhibits Visceral Preadipocyte Browning. EBioMedicine 2022, 78, 103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Navarrete, J.M. Gremlin 2 Could Explain the Reduced Capacity of Browning of Visceral Adipose Tissue. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, C. Identification of Key Genes and Biological Pathways Associated with Vascular Aging in Diabetes Based on Bioinformatics and Machine Learning. Aging 2024, 16, 9369–9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, K.; Ishikawa, A. Genetic Identification of Ly75 as a Novel Quantitative Trait Gene for Resistance to Obesity in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Zeng, L.-T.; Wang, J.-J.; Liu, Z.; Fan, G.-Q.; Li, J.; Cai, J.-P. Long-Term High-Fat High-Fructose Diet Induces Type 2 Diabetes in Rats through Oxidative Stress. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițulescu, I.M.; Ciulei, G.; Cozma, A.; Procopciuc, L.M.; Orășan, O.H. From Innate Immunity to Metabolic Disorder: A Review of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in Diabetes Mellitus. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milan, K.L.; Nandhana, N.; Shree, R.A.; Leela, R.; Jahnavi, S.; Anuradha, M.; Ramkumar, K.M. NEK7-Mediated Activation of NLRP1 and NLRP3 Inflammasomes in the Progression of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Hum. Immunol. 2025, 86, 111331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Lian, C.; Chen, G.; Zou, P.; Qin, B.G. Ginsenoside CK Targets NEK7 to Suppress Inflammasome Activation and Mitigate Diabetes-Induced Muscle Atrophy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 321, 146174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Huneidi, W.; Anjum, S.; Mohammed, A.K.; Unnikannan, H.; Saeed, R.; Bajbouj, K.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Taneera, J. Copine 3 “CPNE3” Is a Novel Regulator for Insulin Secretion and Glucose Uptake in Pancreatic β-Cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Z.; Peterson, J.M.; Lei, X.; Cebotaru, L.; Wolfgang, M.J.; Baldeviano, G.C.; Wong, G.W. C1q/TNF-Related Protein-12 (CTRP12), a Novel Adipokine That Improves Insulin Sensitivity and Glycemic Control in Mouse Models of Obesity and Diabetes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 10301–10315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. MTHFR Gene Polymorphisms in Diabetes Mellitus. Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 561, 119825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, K.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.; Zhao, M.; Guan, M.-X.; Qin, G. Association of MTHFR C677T Polymorphism and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) Susceptibility. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2019, 7, e1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana Bezerra, H.; Severo de Assis, C.; Dos Santos Nunes, M.K.; Wanderley de Queiroga Evangelista, I.; Modesto Filho, J.; Alves Pegado Gomes, C.N.; Ferreira do Nascimento, R.A.; Pordeus Luna, R.C.; de Carvalho Costa, M.J.; de Oliveira, N.F.P.; et al. The MTHFR Promoter Hypermethylation Pattern Associated with the A1298C Polymorphism Influences Lipid Parameters and Glycemic Control in Diabetic Patients. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, N.; Chen, S.; Wu, X.; Li, L. Immune Repertoire and Evolutionary Trajectory Analysis in the Development of Diabetic Nephropathy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1006137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, R.A.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Castañé, H.; Jiménez-Franco, A.; Joven, J.; Burks, D.J.; Galán, A.; García-García, F. Landscape of Sex Differences in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes in Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Transcriptomics Studies. Metabolism 2025, 168, 156241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.K.; Sutherland, J.R.; Elson, G.R.; Piaggi, P.; Kobes, S.; Hanson, R.L.; Clifton, B.I.I.I.; Baier, L. A Low-Frequency Amerindian Specific Variant in PALD1, a Negative Regulator of Insulin Signaling, Associates with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67, 213-LB. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Lai, Y.; He, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhu, X.; Zhuang, S. Lysine Acetyltransferase 5 Contributes to Diabetic Retinopathy by Modulating Autophagy through Epigenetically Regulating Autophagy-Related Gene 7. Cytojournal 2025, 22, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snapes, E.; Astrin, J.J.; Bertheussen Krüger, N.; Grossman, G.H.; Hendrickson, E.; Miller, N.; Seiler, C. Updating International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories Best Practices, Fifth Edition: A New Process for Relevance in an Evolving Landscape. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2023, 21, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI-Generated RNA-Seq Count dataBETA. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/info/rnaseqcounts.html (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Hubert, M.; Reynkens, T.; Schmitt, E.; Verdonck, T. Sparse PCA for High-Dimensional Data With Outliers. Technometrics 2016, 58, 424–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staedtler, F.; Hartmann, N.; Letzkus, M.; Bongiovanni, S.; Scherer, A.; Marc, P.; Johnson, K.J.; Schumacher, M.M. Robust and Tissue-Independent Gender-Specific Transcript Biomarkers. Biomark. Biochem. Indic. Expo. Response Susceptibility Chem. 2013, 18, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, G.E.; Roussos, P. Dream: Powerful Differential Expression Analysis for Repeated Measures Designs. Bioinformatics 2021, 37, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, A.; Marot, G.; Jaffrézic, F. Differential Meta-Analysis of RNA-Seq Data from Multiple Studies. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finotello, F.; Mayer, C.; Plattner, C.; Laschober, G.; Rieder, D.; Hackl, H.; Krogsdam, A.; Loncova, Z.; Posch, W.; Wilflingseder, D.; et al. Molecular and Pharmacological Modulators of the Tumor Immune Contexture Revealed by Deconvolution of RNA-Seq Data. Genome Med. 2019, 11, 34, Correction in Genome Med. 2019, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Huber, W. Differential Expression Analysis for Sequence Count Data. Genome Biol. 2010, 11, R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Parmigiani, G.; Johnson, W.E. ComBat-Seq: Batch Effect Adjustment for RNA-Seq Count Data. NARGenom. Bioinform. 2020, 2, lqaa078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accession | Citation | Samples Healthy | Samples T2D | Samples Healthy After Filtering Outliers | Samples T2D After Filtering Outliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE280402 | this study | 8 | 8 | 7 | 7 |

| GSE154881 | no | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| GSE153315 | no | 10 | 20 | 9 | 14 |

| GSE184050 | [4] | 66 | 50 | 53 | 35 |

| GSE221521 | [5] | 50 | 74 | 45 | 61 |

| GSE185011 | [6] | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| GSE181143 | [7] | 294 | 259 | 259 | 234 |

| GSE114192 | [8] | 82 | 113 | 75 | 99 |

| Total | 520 | 534 | 457 | 458 |

| Accession | Formula | # of DEGs |

|---|---|---|

| GSE280402 | ~0 + condition + sex | 0 |

| GSE154881 | ~0 + condition + sex | 3417 |

| GSE153315 | ~0 + condition + sex | 0 |

| GSE184050 | ~0 + condition + sex + timepoint + (1|individual) | 1 |

| GSE221521 | ~0 + condition + sex | 0 |

| GSE185011 | ~0 + condition + sex | 0 |

| GSE181143 | ~0 + condition + sex + tuberculosis_status + timepoint + site + (1|individual) | 142 |

| GSE114192 | ~0 + condition + sex + tuberculosis_status + site | 3023 |

| Characteristics | T2D (N = 8) | Controls (N = 8) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.3 | 56.6 | 0.35 |

| Female (n) | 5 | 5 | NA |

| Male (n) | 4 | 4 | NA |

| Family history (n) | 1 | 5 | NA |

| Fasting blood glucose * | 8.8 | 4.7 | 0.0096 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.8 | 6.7 | 0.33 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.75 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3 | 4.4 | 0.25 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.14 |

| BMI (kg/m2) * | 32 | 24.5 | 0.0007 |

| WHR * | 1 | 0.76 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tkachenko, A.A.; Tonyan, Z.N.; Nasykhova, Y.A.; Barbitoff, Y.A.; Renev, I.N.; Danilova, M.M.; Basipova, A.A.; Glavnova, O.B.; Polev, D.E.; Chepanov, S.V.; et al. Cross-Study Meta-Analysis of Blood Transcriptomes in Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412046

Tkachenko AA, Tonyan ZN, Nasykhova YA, Barbitoff YA, Renev IN, Danilova MM, Basipova AA, Glavnova OB, Polev DE, Chepanov SV, et al. Cross-Study Meta-Analysis of Blood Transcriptomes in Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412046

Chicago/Turabian StyleTkachenko, Aleksandr A., Ziravard N. Tonyan, Yulia A. Nasykhova, Yury A. Barbitoff, Iaroslav N. Renev, Maria M. Danilova, Anastasiia A. Basipova, Olga B. Glavnova, Dmitrii E. Polev, Sergey V. Chepanov, and et al. 2025. "Cross-Study Meta-Analysis of Blood Transcriptomes in Type 2 Diabetes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412046

APA StyleTkachenko, A. A., Tonyan, Z. N., Nasykhova, Y. A., Barbitoff, Y. A., Renev, I. N., Danilova, M. M., Basipova, A. A., Glavnova, O. B., Polev, D. E., Chepanov, S. V., Selkov, S. A., Golovkin, N. V., Vlasova, M. E., & Glotov, A. S. (2025). Cross-Study Meta-Analysis of Blood Transcriptomes in Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12046. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412046