A Family with Meester–Loeys Syndrome Caused by a Novel Missense Variant in the BGN Gene

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Data

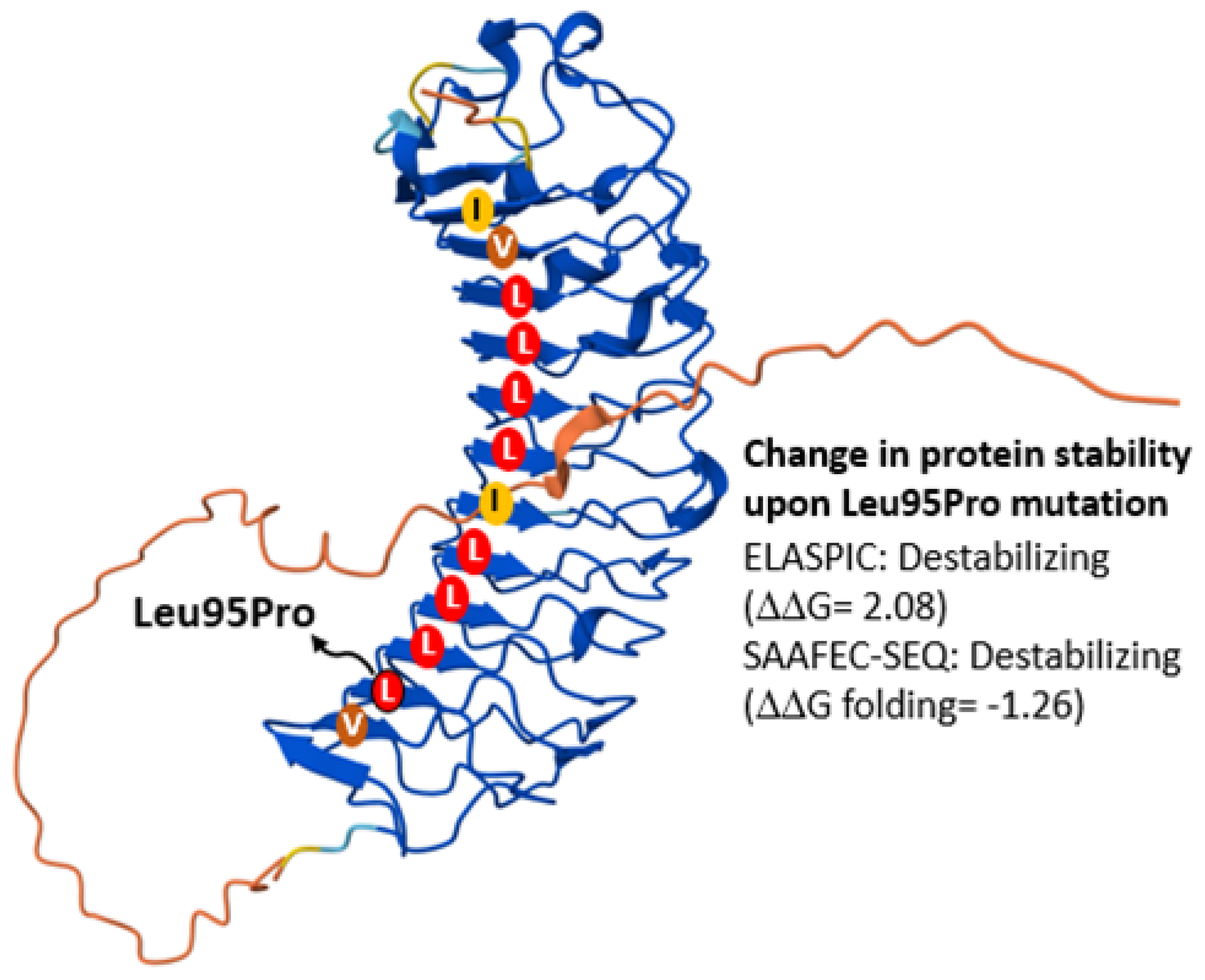

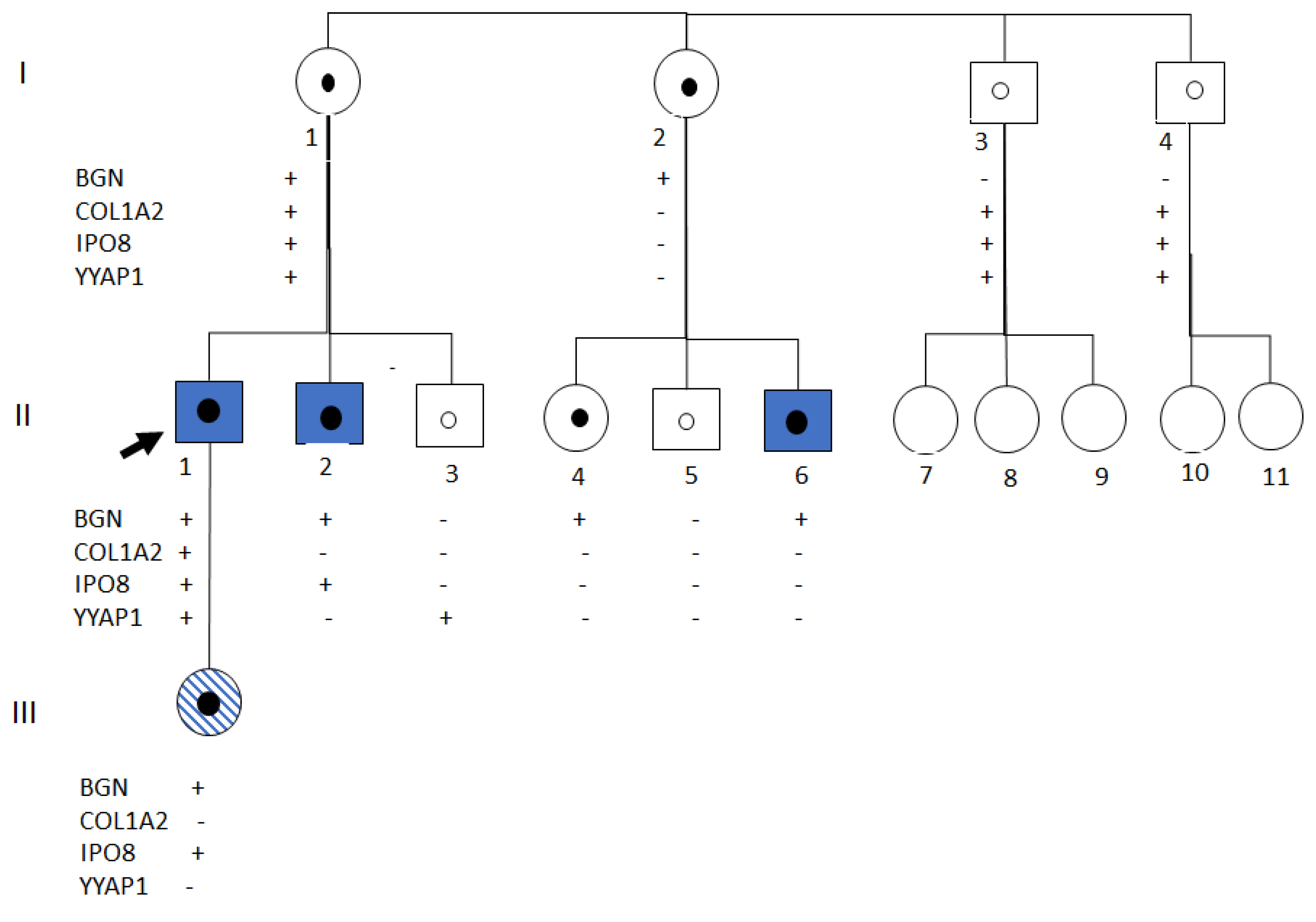

2.2. Genetic Analysis

2.3. Functional Studies

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Clinical Procedures

4.2. Genetic Analyses

4.3. Fibroblast Proliferation

4.4. Cloning and Transfection Experiments

4.5. Western Blot

4.6. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

4.7. Gene Expression

4.8. Artificial Intelligence Tools

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowen, J.M.; Hernandez, M.; Johnson, D.S.; Green, C.; Kammin, T.; Baker, D.; Keigwin, S.; Makino, S.; Taylor, N.; Watson, O.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Vascular Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: Experience of the UK National Diagnostic Service, Sheffield. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2023, 31, 749–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfait, F.; Castori, M.; Francomano, C.A.; Giunta, C.; Kosho, T.; Byers, P.H. The Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meester, J.A.N.; Verstraeten, A.; Schepers, D.; Alaerts, M.; Van Laer, L.; Loeys, B.L. Differences in Manifestations of Marfan Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and Loeys-Dietz Syndrome. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2017, 6, 582–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Jia, P.; Feng, X.; Zhang, D. Marfan Syndrome: Insights from Animal Models. Front. Genet. 2025, 15, 1463318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.C.Y. Pathology and Pathophysiology of the Aortic Root. Ann. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2023, 12, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J.; Sheppard, D. TGF-β Signaling in Health and Disease. Cell 2023, 186, 4007–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Qu, C.; Jia, P.; Zhang, D.D. Therapeutic Opportunities of Marfan Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2025, 19, 7365–7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.B.; Ikonomidis, J.S.; Jones, J.A. Connective Tissue Disorders and Cardiovascular Complications: The Indomitable Role of Transforming Growth Factor-β Signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1348, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, J.A.N.; De Kinderen, P.; Verstraeten, A.; Loeys, B. Meester-Loeys Syndrome. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1348, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez, P.A. Evidence of Biglycan Structure-Function in Bone Homeostasis and Aging. Connect. Tissue Res. 2020, 61, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, E.Y.; Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. The Wnt Pathway: From Signaling Mechanisms to Synthetic Modulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fooks, H.M.; Martin, A.C.R.; Woolfson, D.N.; Sessions, R.B.; Hutchinson, E.G. Amino Acid Pairing Preferences in Parallel β-Sheets in Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 356, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Panday, S.K.; Alexov, E. SAAFEC-SEQ: A Sequence-Based Method for Predicting the Effect of Single Point Mutations on Protein Thermodynamic Stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berliner, N.; Teyra, J.; Çolak, R.; Lopez, S.G.; Kim, P.M. Combining Structural Modeling with Ensemble Machine Learning to Accurately Predict Protein Fold Stability and Binding Affinity Effects upon Mutation. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, A.F.; Demirdas, S.; Fournel-Gigleux, S.; Ghali, N.; Giunta, C.; Kapferer-Seebacher, I.; Kosho, T.; Mendoza-Londono, R.; Pope, M.F.; Rohrbach, M.; et al. The Ehlers-Danlos Syndromes, Rare Types. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2017, 175, 70–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.C.; Duan, X.Y.; Regalado, E.S.; Mellor-Crummey, L.; Kwartler, C.S.; Kim, D.; Lieberman, K.; de Vries, B.B.A.; Pfundt, R.; Schinzel, A.; et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in YY1AP1 Lead to Grange Syndrome and a Fibromuscular Dysplasia-Like Vascular Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 100, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gucht, I.; Meester, J.A.N.; Bento, J.R.; Bastiaansen, M.; Bastianen, J.; Luyckx, I.; Van Den Heuvel, L.; Neutel, C.H.G.; Guns, P.J.; Vermont, M.; et al. A Human Importin-β-Related Disorder: Syndromic Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm Caused by Bi-Allelic Loss-of-Function Variants in IPO8. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 108, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, J.A.N.; Vandeweyer, G.; Pintelon, I.; Lammens, M.; Van Hoorick, L.; De Belder, S.; Waitzman, K.; Young, L.; Markham, L.W.; Vogt, J.; et al. Loss-of-Function Mutations in the X-Linked Biglycan Gene Cause a Severe Syndromic Form of Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meester, J.A.N.; Hebert, A.; Bastiaansen, M.; Rabaut, L.; Bastianen, J.; Boeckx, N.; Ashcroft, K.; Atwal, P.S.; Benichou, A.; Billon, C.; et al. Expanding the Clinical Spectrum of Biglycan-Related Meester-Loeys Syndrome. NPJ Genom. Med. 2024, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Kinderen, P.; Verstraeten, A.; Loeys, B.L.; Meester, J.A.N. The Role of Biglycan in the Healthy and Thoracic Aneurysmal Aorta. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C1214–C1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shainer, R.; Kram, V.; Kilts, T.M.; Li, L.; Doyle, A.D.; Shainer, I.; Martin, D.; Simon, C.G.; Zeng-Brouwers, J.; Schaefer, L.; et al. Biglycan Regulates Bone Development and Regeneration. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1119368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kram, V.; Shainer, R.; Jani, P.; Meester, J.A.N.; Loeys, B.; Young, M.F. Biglycan in the Skeleton. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2020, 68, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.; Bianco, P.; Fisher, L.W.; Longenecker, G.; Smith, E.; Goldstein, S.; Bonadio, J.; Boskey, A.; Heegaard, A.M.; Sommer, B.; et al. Targeted Disruption of the Biglycan Gene Leads to an Osteoporosis-like Phenotype in Mice. Nat. Genet. 1998, 20, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior-Becker, A.; Dai, G.; Ding, Z.; Schäfer, L.; Schrader, J.; Young, M.F.; Fischer, J.W. Deficiency of Biglycan Causes Cardiac Fibroblasts to Differentiate into a Myofibroblast Phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 17365–17375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Bae, J.S.; Kim, N.K.D.; Forzano, F.; Girisha, K.M.; Baldo, C.; Faravelli, F.; Cho, T.J.; Kim, D.; Lee, K.Y.; et al. BGN Mutations in X-Linked Spondyloepimetaphyseal Dysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastase, M.V.; Young, M.F.; Schaefer, L. Biglycan: A Multivalent Proteoglycan Providing Structure and Signals. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2012, 60, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, A.D.; Fisher, L.W.; Kilts, T.M.; Owens, R.T.; Robey, P.G.; Gutkind, J.S.; Younga, M.F. Modulation of Canonical Wnt Signaling by the Extracellular Matrix Component Biglycan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17022–17027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, V.; Huber, L.S.; Trebicka, J.; Wygrecka, M.; Iozzo, R.V.; Schaefer, L. The Role of Decorin and Biglycan Signaling in Tumorigenesis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 801801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, T.; Yoshida, E.; Shinkai, Y.; Yamamoto, C.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Kaji, T. Biglycan Intensifies ALK5-Smad2/3 Signaling by TGF-Β1 and Downregulates Syndecan-4 in Cultured Vascular Endothelial Cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, A.; Spata, E.; Emberson, J.; Davies, K.; Halls, H.; Holland, L.; Wilson, K.; Reith, C.; Child, A.H.; Clayton, T.; et al. Angiotensin Receptor Blockers and β Blockers in Marfan Syndrome: An Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. Lancet 2022, 400, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isselbacher, E.M.; Preventza, O.; Hamilton Black, J.; Augoustides, J.G.; Beck, A.W.; Bolen, M.A.; Braverman, A.C.; Bray, B.E.; Brown-Zimmerman, M.M.; Chen, E.P.; et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, e223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riancho, J.; Castanedo-Vázquez, D.; Gil-Bea, F.; Tapia, O.; Arozamena, J.; Durán-Vían, C.; Sedano, M.J.; Berciano, M.T.; Lopez de Munain, A.; Lafarga, M. ALS-Derived Fibroblasts Exhibit Reduced Proliferation Rate, Cytoplasmic TDP-43 Aggregation and a Higher Susceptibility to DNA Damage. J. Neurol. 2020, 267, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Syndrome | Meester–Loeys | Loeys–Dietz | Vascular Ehlers-Danlos | Marfan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Very rare | Rare | 1:50,000–150,000 | 1:3000–1:5000 |

| Causal Gene(s) | BGN | TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD2, SMAD3, TGFB2, TGFB3 | COL3A1 | FBN1 |

| Heredity | X-linked | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal dominant |

| Organs Affected | Cardiovascular, skeletal, craniofacial, cutaneous, neurological | Cardiovascular, skeletal, craniofacial, cutaneous | Vascular, cutaneous, gastrointestinal | Cardiovascular, ocular, skeletal |

| Main Manifestations |

|

|

|

|

| Prognosis | Severe in males, milder in females | Poor | Poor | Variable, improved with treatment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Riancho, J.A.; Vega, A.I.; del Real, A.; Sañudo, C.; Pérez-Castrillón, J.L.; García-López, R.; Puente, N.; Nistal, J.F.; Fernández-Luna, J.L. A Family with Meester–Loeys Syndrome Caused by a Novel Missense Variant in the BGN Gene. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412044

Riancho JA, Vega AI, del Real A, Sañudo C, Pérez-Castrillón JL, García-López R, Puente N, Nistal JF, Fernández-Luna JL. A Family with Meester–Loeys Syndrome Caused by a Novel Missense Variant in the BGN Gene. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412044

Chicago/Turabian StyleRiancho, José A., Ana I. Vega, Alvaro del Real, Carolina Sañudo, José L. Pérez-Castrillón, Raquel García-López, Nuria Puente, J. Francisco Nistal, and José L. Fernández-Luna. 2025. "A Family with Meester–Loeys Syndrome Caused by a Novel Missense Variant in the BGN Gene" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412044

APA StyleRiancho, J. A., Vega, A. I., del Real, A., Sañudo, C., Pérez-Castrillón, J. L., García-López, R., Puente, N., Nistal, J. F., & Fernández-Luna, J. L. (2025). A Family with Meester–Loeys Syndrome Caused by a Novel Missense Variant in the BGN Gene. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12044. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412044