Synthesis of Novel Anion Recognition Molecules as Quinazoline Precursors

Abstract

1. Introduction

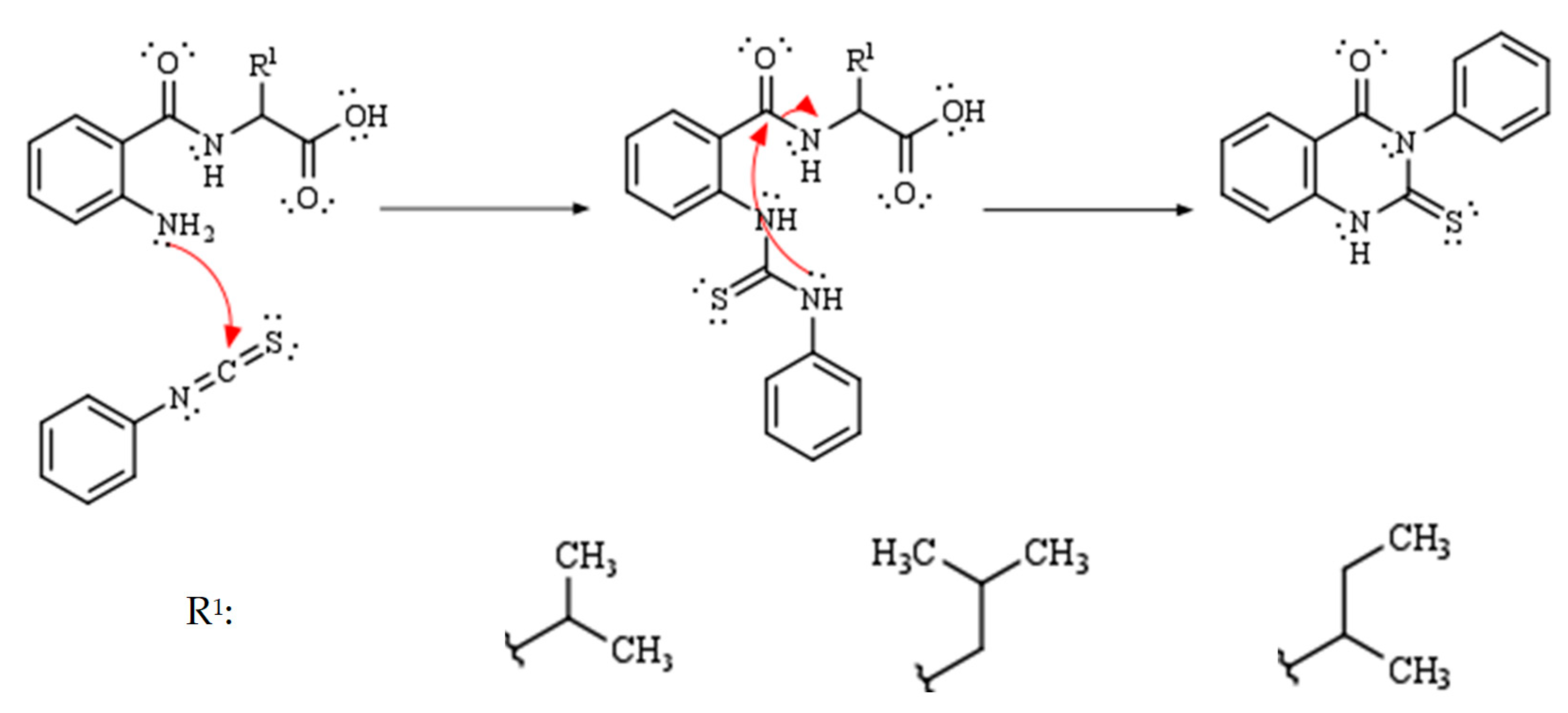

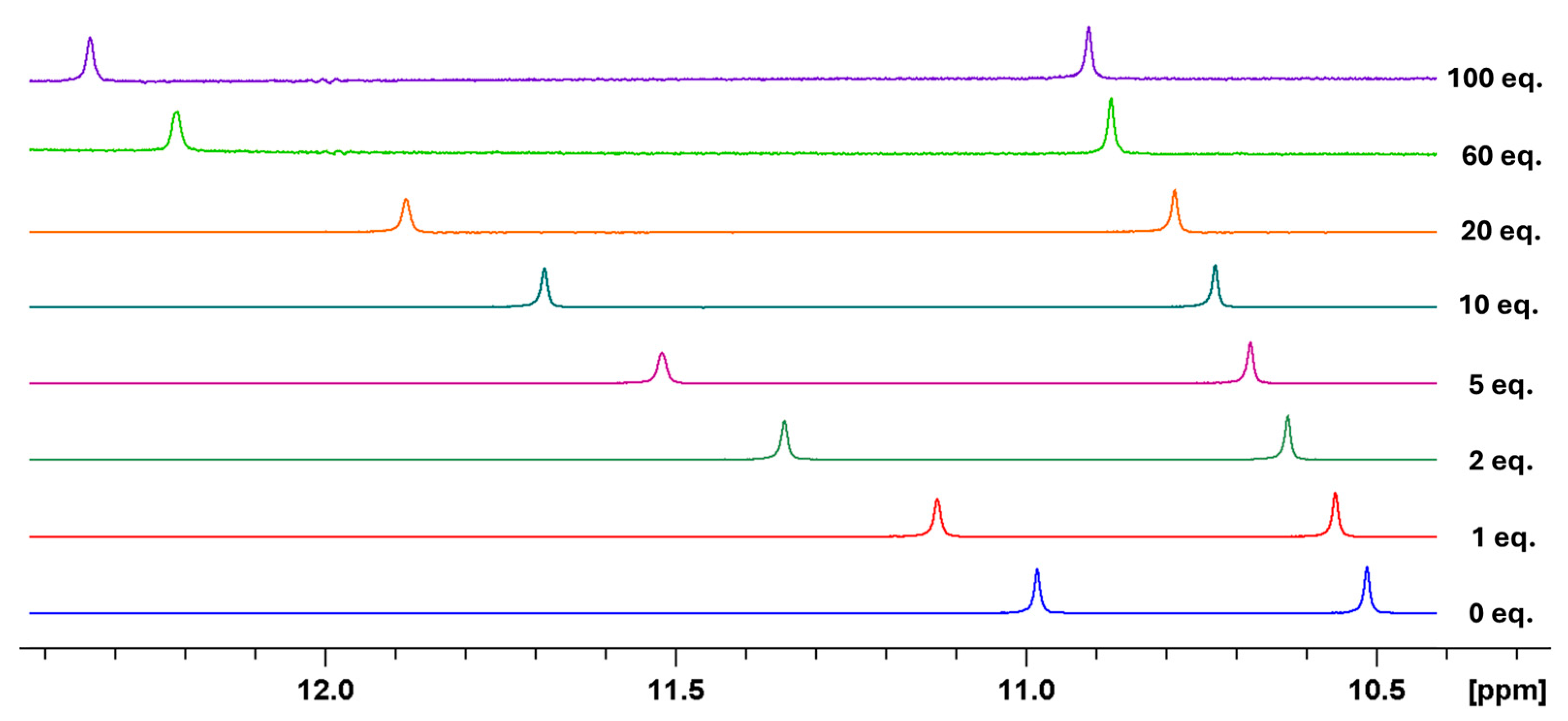

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Data

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gale, P. From Anion Receptors to Transporters. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valkenier, H.; Haynes, C.J.E.; Herniman, J.; Gale, P.; Davis, A.P. Lipophilic balance—A new design for transmembrane anion carriers. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, N.; Gale, P.; Haynes, C.; Light, M.; Moore, S.; Tong, C.; Harrell, W. Tripodal transmembrane transporters for bicarbonate. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 6252–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, N.; Karagiannidis, L.; Wenzel, M.; Haynes, C.; Wells, N.; Young, P.; Gale, P. Synthetic transporters for sulfate: A new method for the direct detection of lipid bilayer sulfate transport. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, L.; Ricci, A.; Wu, X.; Howe, E.; Gale, P. Investigating the influence of steric hindrance on selective anion transport. Molecules 2019, 24, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, H.; Johnson, T.; Docker, A.; Langton, M.; Beer, P. Exploiting the catenane mechanical bond effect for selective halide anion transmembrane transport. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202312745. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, W. Synthesis, anion recognition, and transmembrane anionophoric activity of tripodal diaminocholoyl conjugates. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 13368–13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busschaert, N.; Wenzel, M.; Light, M.; Iglesias-Hernandez, P.; Pérez-Tomás, R.; Gale, P. Structure–activity relationships in tripodal transmembrane anion transporters: The effect of fluorination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14136–14148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, N.; Cuartero, M.; Jowett, L.; Howe, E.; Gale, P.; Bakker, E.; Crespo, G. Fluorinated tripodal receptors for potentiometric chloride detection in biological fluids. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 99, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, P.; Madhavan, N. Macrocyclic transmembrane anion transporters via a one-pot condensation reaction. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 5104–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, H.; Martínez-Crespo, L.; Webb, S.; Dryfe, R. Electrochemical assessment of a tripodal thiourea-based anion receptor at the liquid|liquid interface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25, 18121–18131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Moeini-Naghani, I.; Zhong, S.; Li, F.; Bian, S.; Sigworth, F.; Navaratnam, D. Current carried by the slc26 family member prestin does not flow through the transporter pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, N.; Conthagamage, U.; Bucher, S.; Abdulsalam, Z.; Davis, M.; Beavers, W.; García-López, V. Thiourea-based rotaxanes: Anion transport across synthetic lipid bilayers and antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 8534–8545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Devereux, R.; Russel, A.; Langton, M. Near-infrared triggered anion transport induces cancer cell death. ChemRxiv, 2025; submitted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, N.; Gabbaï, F. Bismuthenium cations for the transport of chloride anions via pnictogen bonding. Angew. Chem. 2024, 137, e202414699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Howe, E.; Gale, P. Supramolecular transmembrane anion transport: New assays and insights. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 1870–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.C. Permeability of membranes to amino acids and modified amino acids: Mechanisms involved in translocation. Amino Acids 1994, 6, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

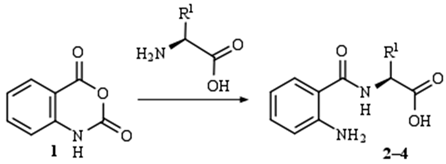

- Bakavoli, M.; Davoodnia, A.; Shahnaee, R. Convenient synthesis of some optically active 1,4-benzodiazepin-2,5-diones. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2008, 19, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresha, G.P.; Suhas, R.; Kapfo, W.; Channe, G.D. Urea/thiourea derivatives of quinazolinone–lysine conjugates: Synthesis and structure–activity relationships of a new series of antimicrobials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.-R.; Lai, N.C.-H.; Kung, K.K.-Y.; Yang, B.; Chung, S.-F.; Leung, A.S.-L.; Choi, M.-C.; Leung, Y.-C.; Wong, M.-K. N-Terminal selective modification of peptides and proteins using 2-ethynylbenzaldehydes. Commun. Chem. 2020, 3, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandão-Lima, L.; Silva, F.; Costa, P.; Alves-Júnior, E.; Viseras, C.; Osajima, J.; Bezerra, L.; Moura, J.; Silva, A.; Fonseca, M.; et al. Clay Mineral Minerals as a Strategy for Biomolecule Incorporation: Amino Acids Approach. Materials 2021, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddick, J.A.; Bunger, W.B.; Sakano, T.K. Organic Solvents: Physical Properties and Methods of Purification, 4th ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1986; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- Feigel, M.; Lugert, G.; Manero, J.; Bremer, M. Konformation von Anthranilsäurepeptiden, 3 [1]: Konformationen kleiner Anthranilsäure-Prolinpeptide im Kristall, in Lösung und eine semiempirische (AM 1) Beschreibung der Prolin-Ramachandran-Hyperflächen. Z. Naturforsch. B 1990, 45, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

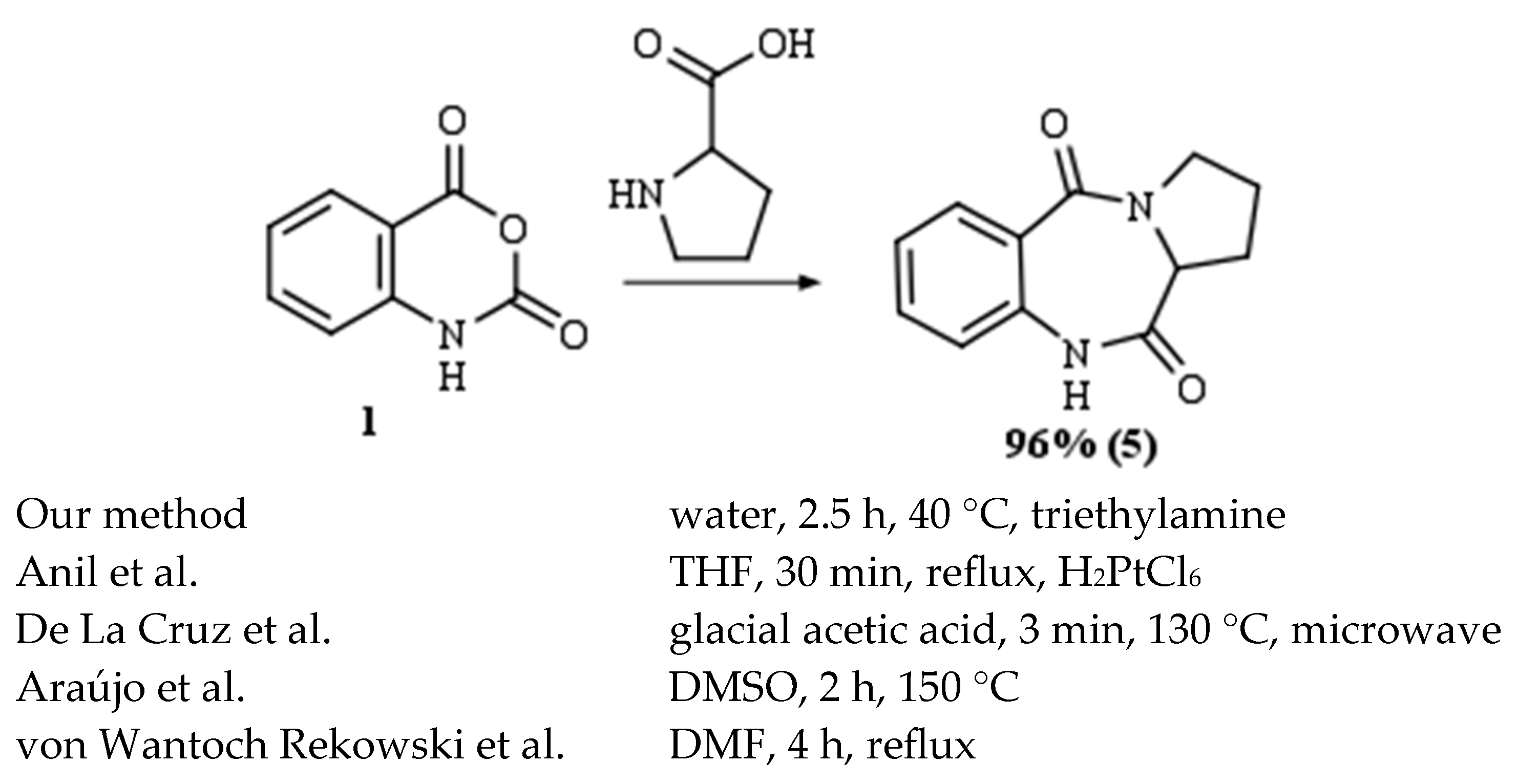

- Anil, S.M.; Shobith, R.; Kiran, K.R.; Swaroop, T.R.; Mallesha, N.; Sadashiva, M.P. Facile synthesis of 1,4-benzodiazepine-2,5-diones and quinazolinones from amino acids as anti-tubercular agents. New. J. Chem. 2019, 43, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz, A.; Vega-Acevedo, C.A.; Rivero, I.A.; Chávez, D. Improved method for microwave-assisted synthesis of benzodiazepine-2, 5-diones from isatoic anhydrides mediated by glacial acetic acid. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2018, 29, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.C.; Rauter, A.P.; Nicotra, F.; Airold, C.; Costa, B.; Cipolla, L. Sugar-Based Enantiomeric and Conformationally Constrained Pyrrolo[2,1-c][1,4]-Benzodiazepines as Potential GABAA Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- von Wantoch Rekowski, M.; Pyriochou, A.; Papapetropoulos, N.; Stößel, A.; Papapetropoulos, A.; Giannis, A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of oxadiazole derivatives as inhibitors of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamara, B.; Kamara, H.; Phambu, N. pH-Dependent Ion Binding Studies on 2-Mercaptopyrimidine. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 5, 2380–2391. [Google Scholar]

- Piros, L.; Krajsovszky, G.; Bogdán, D.; Gáti, T.; Szabó, P.; Horváth, P.; Mándity, I.M. Energy-Efficient Synthesis of Haloquinazolines and Their Suzuki Cross-Coupling Reactions in Propylene Carbonate. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202304969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Crich, D. Facile Amide Bond Formation from Carboxylic Acids and Isocyanates. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2256–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigier, J.; Gao, M.; Jubault, P.; Lebel, H.; Besset, T. Divergent process for the catalytic decarboxylative thiocyanation and isothiocyanation of carboxylic acids promoted by visible light. Chem. Comm. 2024, 60, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Gupta, S.V.; Lee, K.-D.; Amidon, G.L. Chemical and Enzymatic Stability of Amino Acid Prodrugs Containing Methoxy, Ethoxy and Propylene Glycol Linkers. Mol. Pharm. 2009, 6, 1604–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagarsamy, V.; Raja Solomon, V.; Dhanabal, K. Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of some 3-phenyl-2-substituted-3H-quinazolin-4-one as analgesic, anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobinath, M.; Subramanian, N.; Alagarsamy, V.; Nivedhitha, S.; Solomon, V.R. Design and Synthesis of 1-Substituted-4-(4-Nitrophenyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinazolin-5(4H)-ones as a New Class of Antihistaminic Agents. Russ. J. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 46, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Jonathan, E.; Marcel, K.; Reto, B.; John, L.; Colin, B.; Ian, H. Analogues of thiolactomycin as potential antimalarial agents. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5932–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gondi, S.R.; Bera, A.K.; Westover, K.D. Green Synthesis of Substituted Anilines and Quinazolines from Isatoic Anhydride-8-amide. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14258, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20379.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.A. One-pot Syntheses of Some New 2,4(1H,3H)-quinazolinedione Derivatives in the Absence of Catalyst. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 2075–2078. [Google Scholar]

- van Zyl, E.F. A survey of reported synthesis of methaqualone and some positional and structural isomers. Forensic Sci. Int. 2001, 122, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Song, Z.; Tang, Z. Facile and efficient synthesis and biological evaluation of 4-anilinoquinazoline derivatives as EGFR inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2589–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Süsse, M.; Johne, S. Chinazolincarbonsäuren. VII. Mitteilung. Ein einfacher Zugang zu (4-Oxo-3,4-dihydrochinazolin-3-yl)-alkansäuren, (4-Oxo-3,4-dihydro-1,2,3-benzotriazin-3-yl)-alkansäuren und deren Estern. Helv. Chim. Acta 1985, 68, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Joshi, A.; Rawat, D.; Adimurthy, S. Synthesis of thiazolidinimines/thiazinan-2-imines via three-component coupling of amines, vic-dihalides and isothiocyanates under metal-free conditions. Synth. Commun. 2021, 51, 1340–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Sudan, S.; Chen, D.W.; Berton, C.; Fadaei-Tirani, F.; Severin, K. Synthetic Receptors with Micromolar Affinity for Chloride in Water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202218072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picci, G.; Montis, R.; Lippolis, V.; Caltagirone, C. Squaramide-based receptors in anion supramolecular chemistry: Insights into anion binding, sensing, transport and extraction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 3952–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plais, R.; Gouarin, G.; Bournier, A.; Zayene, O.; Mussard, V.; Bourdreux, F.; Marrot, J.; Brosseau, A.; Gaucher, A.; Clavier, G.; et al. Chloride Binding Modulated by Anion Receptors Bearing Tetrazine and Urea. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2023, 24, e202200524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindfit. Available online: http://app.supramolecular.org/bindfit/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

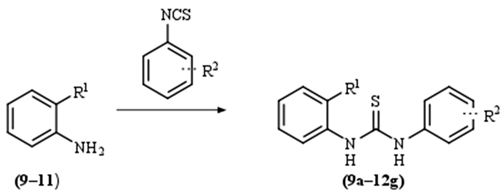

| |||

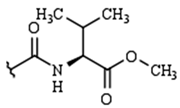

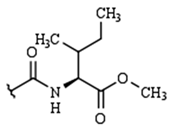

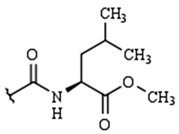

| R1: |  |  |  |

| 79% (2) | 83% (3) | 81% (4) | |

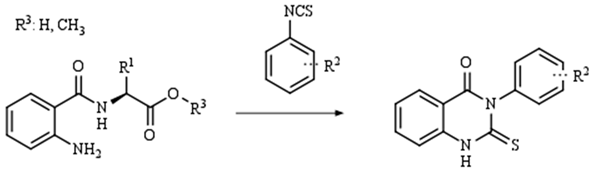

| |||

| R1: |  |  |  |

| R2: | H (6) | 4-NO2 (7) | 3,5-diCF3 (8) |

| |||

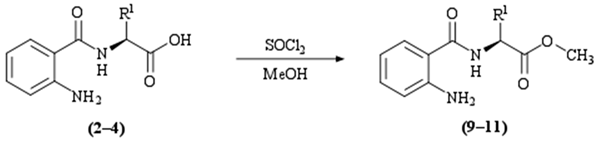

| R1: |  |  |  |

| 68% (9) | 85% (10) | 76% (11) | |

| |||||

| R2: |  |  |  | H | |

| R1: | |||||

| H | 9a | 10a | 11a | 12a | |

| 24 h (DMF) 52% | 22 h (DMF) 73% | 9 h (DMF) 54% | 7 h 84% | ||

| 4.0 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.4 | ||

| 4-NO2 | 9b | 10b | 11b | 12b | |

| 7 h 93% | 5 h 80% | 6 h 82% | 2 h 98% | ||

| 8.1 ± 0.5 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 146.6 ± 8.9 | ||

| 3,5-di-CF3 | 9c | 10c | 11c | 12c | |

| 6h 90% | 2 h 63% | 4 h 90% | 1 h 88% | ||

| 7.1 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 7.7 ± 0.4 | 38.4 ± 0.4 | ||

| 4-CH3O | 9d | 10d | 11d | 12d | |

| 120 h (DMF) 42% | 82 h (DMF) 74% | 76 h (DMF) 74% | 6 h 68% | ||

| 2.7 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 15.9 ± 0.5 | ||

| 4-F | 9e | 10e | 11e | 12e | |

| 22 h (DMF) 81% | 100 h 54% | 24 h (DMF) 36% | 2 h 88% | ||

| 4.9 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 28.6 ± 0.7 | ||

| 3,5-di-F | 9f | 10f | 11f | 12f | |

| 8 h 97% | 9 h 77% | 3 h 84% | 2 h 91% | ||

| 6.9 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 42.4 ± 0.7 | ||

| 2,6-di-F | 9g | 10g | 11g | 12g | |

| 24 h 91% | 20 h 65% | 22 h 75% | 2 h 83% | ||

| 2.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 19.8 ± 0.4 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Krajsovszky, G.; Piros, L.; Bogdán, D.; Kalydi, E.; Gáti, T.; Szabó, P.; Horváth, P.; Mándity, I.M. Synthesis of Novel Anion Recognition Molecules as Quinazoline Precursors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411975

Krajsovszky G, Piros L, Bogdán D, Kalydi E, Gáti T, Szabó P, Horváth P, Mándity IM. Synthesis of Novel Anion Recognition Molecules as Quinazoline Precursors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411975

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrajsovszky, Gábor, László Piros, Dóra Bogdán, Eszter Kalydi, Tamás Gáti, Pál Szabó, Péter Horváth, and István M. Mándity. 2025. "Synthesis of Novel Anion Recognition Molecules as Quinazoline Precursors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411975

APA StyleKrajsovszky, G., Piros, L., Bogdán, D., Kalydi, E., Gáti, T., Szabó, P., Horváth, P., & Mándity, I. M. (2025). Synthesis of Novel Anion Recognition Molecules as Quinazoline Precursors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411975