Gestational and Lactational Exposure to BPS Triggers Microglial Ferroptosis via the SLC7A11/GPX4 Antioxidant Axis and Induces Memory Impairment in Offspring Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Perinatal BPS Exposure Induces Cognitive Deficits and an Anxiety-like Phenotype in Offspring Mice

2.2. Perinatal BPS Exposure Impairs Hippocampal Synaptic Integrity in Offspring Mice

2.3. BPS Exposure During Pregnancy and Lactation Leads to Iron Accumulation and Oxidative Stress in the Brain of Offspring Mice

2.4. Pregnancy and Lactation BPS Exposure Induces Ferroptosis in the Brains of Offspring Mice

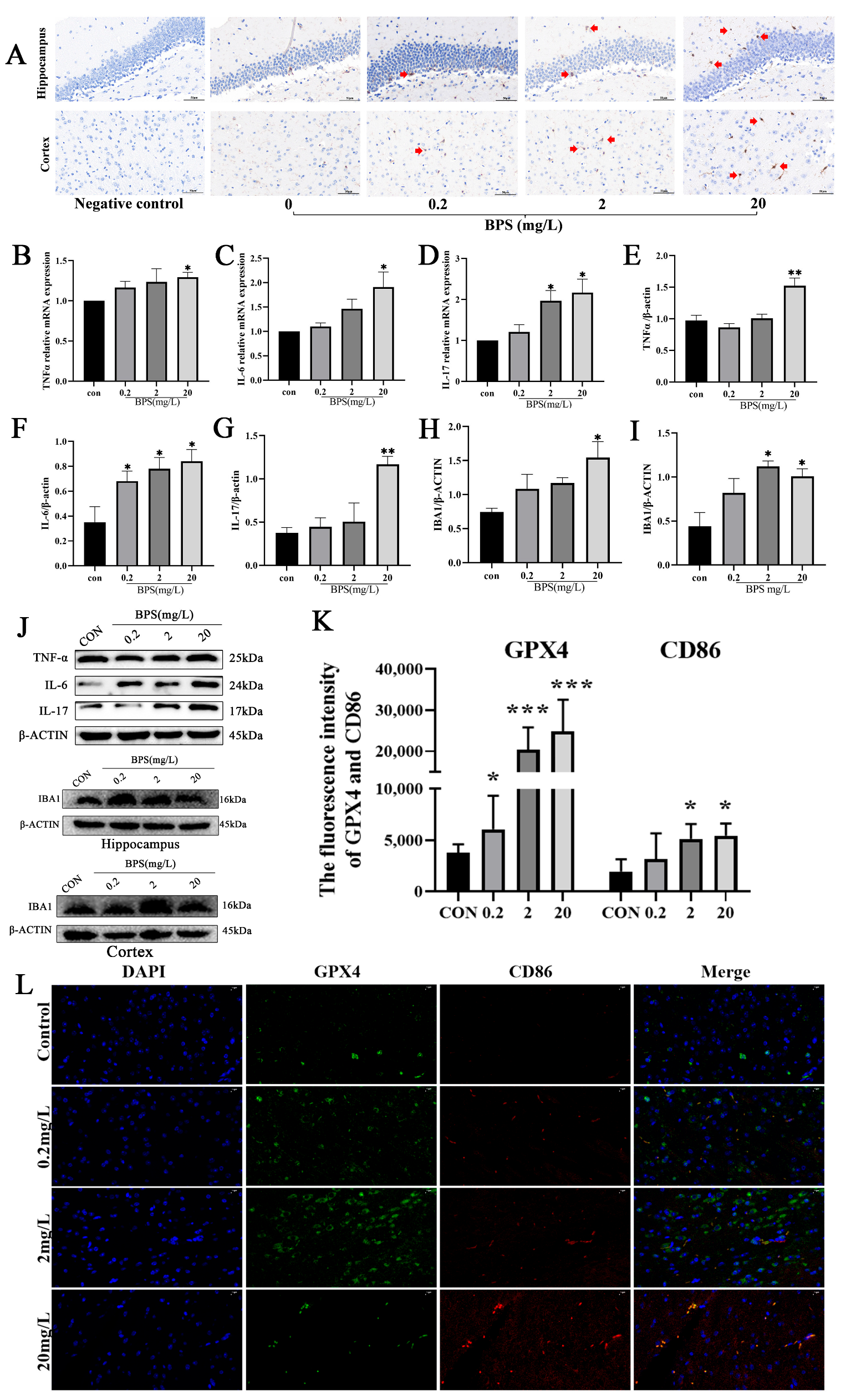

2.5. Pregnancy and Lactation BPS Exposure Induces Ferroptosis and Activates Microglia in Offspring Mice

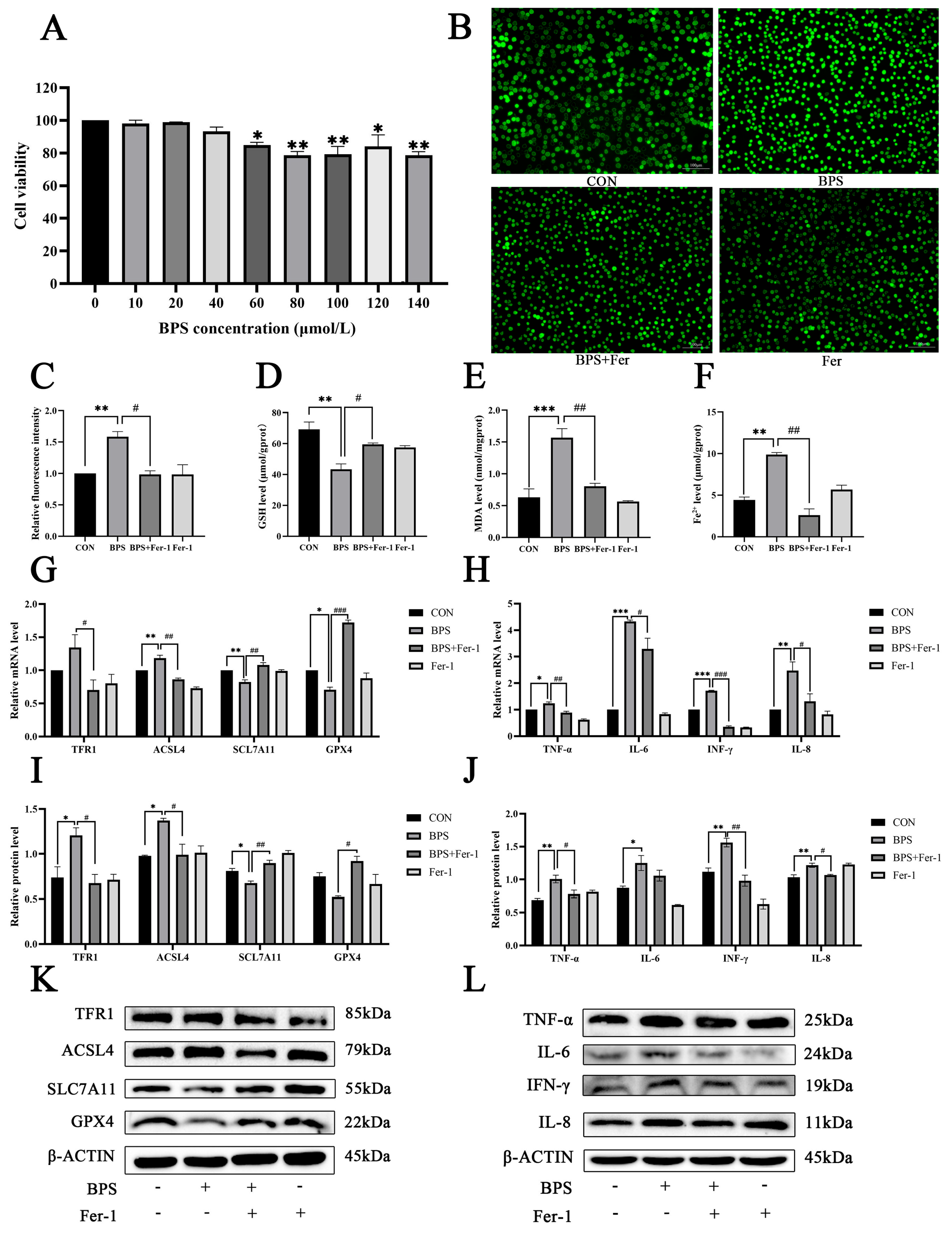

2.6. Fer-1 Inhibited the Release of Inflammatory Factors in BV2 Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Animal Experiments

4.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

4.3. Open Field Test (OFT)

4.4. Morris Water Maze Experiment (MWM)

4.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

4.6. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) Analysis

4.7. Cellular Culture and Viability Assay

4.8. Immunofluorescence

4.9. Determination of Oxidative Stress Index and Iron

4.10. Reactive Oxygen Species Assay

4.11. Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.12. Western Blotting (WB)

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, D.; Kannan, K.; Tan, H.; Zheng, Z.; Feng, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.; Widelka, M. Bisphenol Analogues Other Than BPA: Environmental Occurrence, Human Exposure, and Toxicity—A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 5438–5453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, T.; Fang, M. Revealing Ferroptosis Induction by Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S through Distinct Protein Targets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 21898–21909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Kannan, K. Concentrations and Profiles of Bisphenol A and Other Bisphenol Analogues in Foodstuffs from the United States and Their Implications for Human Exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4655–4662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, L.S. Aerobic Soil Biodegradation of Bisphenol (BPA) Alternatives Bisphenol S and Bisphenol AF Compared to BPA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 13698–13704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Ao, J.; Li, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, Y. Maternal concentrations of environmental phenols during early pregnancy and behavioral problems in children aged 4 years from the Shanghai Birth Cohort. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 933, 172985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y.; Xiong, C.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; et al. Prenatal exposure to bisphenol A and its alternatives and child neurodevelopment at 2 years. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 388, 121774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, B.S.; Pietrobon, C.B.; Bertasso, I.M.; Lopes, B.P.; Carvalho, J.C.; Peixoto-Silva, N.; Santos, T.R.; Claudio-Neto, S.; Manhães, A.C.; Oliveira, E.; et al. Short and long-term effects of bisphenol S (BPS) exposure during pregnancy and lactation on plasma lipids, hormones, and behavior in rats. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, M.; Zhuo, J.; Li, L. An accurate and sensitive method for neurotoxicity assessment of emerging contaminants in zebrafish. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 300, 118438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Li, J.-R.; Yu, H.; Li, S.; Tychhon, B.; Cheng, C.; Weng, Y.-L. Perfluoroalkyl substance pollutants disrupt microglia function and trigger transcriptional and epigenomic changes. Toxicology 2025, 517, 154198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, J.R.; Hilton, J.B.W.; Kysenius, K.; Billings, J.L.; Nikseresht, S.; McInnes, L.E.; Hare, D.J.; Paul, B.; Mercer, S.W.; Belaidi, A.A.; et al. Microglial ferroptotic stress causes non-cell autonomous neuronal death. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: The roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, P.J.; Bórquez, D.A.; Núñez, M.T. Inflaming the Brain with Iron. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, N.; Jiang, H.; Wang, J.; Xie, J. Pro-inflammatory cytokines modulate iron regulatory protein 1 expression and iron transportation through reactive oxygen/nitrogen species production in ventral mesencephalic neurons. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keleş, E.; Aral, L.A.; Elmazoğlu, Z.; Kazan, H.H.; Topa, E.G.A.; Ergün, M.A.; Bolay, H. Phthalate exposure induces cell death and ferroptosis in neonatal microglial cells. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2024, 54, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Zhang, Q.; Siebert, H.-C.; Loers, G.; Wen, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Han, J.; Zhang, N. Semaglutide attenuates Alzheimer’s disease model progression by targeting microglial NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neuroinflammation and ferroptosis. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 396, 115537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cai, X.; Li, R. Ferroptosis Induced by Pollutants: An Emerging Mechanism in Environmental Toxicology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 2166–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, N.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, N. Potential involvement of ferroptosis in BPA-induced neurotoxicity: An in vitro study. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 106, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Sha, M.; Qin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Chen, S. Bisphenol A induces placental ferroptosis and fetal growth restriction via the YAP/TAZ-ferritinophagy axis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 211, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Huang, R.; Sun, F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q. NADPH oxidase regulates paraquat and maneb-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration through ferroptosis. Toxicology 2019, 417, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Gui, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Pang, Q.; Fan, R. Low-dose bisphenols exposure sex-specifically induces neurodevelopmental toxicity in juvenile rats and the antagonism of EGCG. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezak, K.R.; Missig, G.; Carlezon, W.A., Jr. Behavioral methods to study anxiety in rodents. Transl. Res. 2017, 19, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayton, S.; Portbury, S.; Kalinowski, P.; Agarwal, P.; Diouf, I.; Schneider, J.A.; Morris, M.C.; Bush, A.I. Regional brain iron associated with deterioration in Alzheimer’s disease: A large cohort study and theoretical significance. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.P.; Kumar, A.; Prajapati, J.; Bijalwan, V.; Kumar, J.; Amin, P.; Kandoriya, D.; Vidhani, H.; Patil, G.P.; Bishnoi, M.; et al. Sexual dimorphism in neurobehavioural phenotype and gut microbial composition upon long-term exposure to structural analogues of bisphenol-A. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 476, 135178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraguti, G.; Terracina, S.; Micangeli, G.; Lucarelli, M.; Tarani, L.; Ceccanti, M.; Spaziani, M.; D’oRazi, V.; Petrella, C.; Fiore, M. NGF and BDNF in pediatrics syndromes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 145, 105015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wu, M.; Cai, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, M.; Yang, H. Prenatal alcohol exposure impairs offspring cognition through oxidative stress disrupting CREB/BDNF/TrkB signaling and GABAergic neuron deficits. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2025, 207, 115820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, M.; Guo, X.; Xu, N.; Su, Y.; Pan, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zeng, H. Puerarin Attenuates the Cytotoxicity Effects of Bisphenol S in HT22 Cells by Regulating the BDNF/TrkB/CREB Signaling Pathway. Toxics 2025, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-X.; He, Q.-Z.; Li, W.; Long, D.-X.; Pan, X.-Y.; Chen, C.; Zeng, H.-C. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Mediated Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Induced-Neurotoxicity via Epigenetics Regulation in SK-N-SH Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Gu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, M.; Gong, Q.; Xu, J. NSCs promote hippocampal neurogenesis, metabolic changes and synaptogenesis in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Hippocampus 2017, 27, 1250–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coley, A.A.; Gao, W.-J. PSD95: A synaptic protein implicated in schizophrenia or autism? Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 82, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Niu, Q.; Xia, T.; Zhou, G.; Li, P.; Zhao, Q.; Xu, C.; Dong, L.; Zhang, S.; Wang, A. ERK1/2-mediated disruption of BDNF–TrkB signaling causes synaptic impairment contributing to fluoride–induced developmental neurotoxicity. Toxicology 2018, 410, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliegauf, M.; Prinz, M. Too sweet to be savory: How fructose elicits microglia-driven disturbance of neurodevelopment. Cell Res. 2025, 35, 930–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eteng, O.E.; Ugwor, E.I.; James, A.S.; Moses, C.A.; Ogbonna, C.U.; Iwara, I.A.; Akamo, A.J.; Akintunde, J.K.; Blessing, O.A.; Tola, Y.M.; et al. Vanillic acid ameliorates diethyl phthalate and bisphenol S--induced oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of experimental rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e70017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, M.; Bai, S.; Ni, Y.; Xu, Q.; Fan, Y.; Lu, C.; Xu, Z.; Ji, C.; et al. Early-life bisphenol AP exposure impacted neurobehaviors in adulthood through microglial activation in mice. Chemosphere 2023, 317, 137935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.-Y.; Liang, L.-F.; Shi, T.-L.; Shen, Z.-Q.; Yin, S.-Y.; Zhang, J.-R.; Li, W.; Mi, W.-L.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; et al. Microglia-Derived Interleukin-6 Triggers Astrocyte Apoptosis in the Hippocampus and Mediates Depression--Like Behavior. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruol, D.L. IL-6 regulation of synaptic function in the CNS. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Yang, Y.; Lang, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Meng, J.; Wu, J.; Zeng, X.; Li, H.; Ma, H.; et al. SIRT1/FOXO3-mediated autophagy signaling involved in manganese-induced neuroinflammation in microglia. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Guo, Y.; Tao, L.; Fan, X. Ferroptosis-driven neurobehavioral impairment in zebrafish embryos: Mechanistic links to developmental dibutyl phthalate exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 384, 127009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, C.; Li, Z.; Huang, W.; Zheng, S.; Liu, C.; Shi, X.; Ma, Y.; Ni, Q.; Tan, W.; et al. Astaxanthin activates the Nrf2/Keap1/HO-1 pathway to inhibit oxidative stress and ferroptosis, reducing triphenyl phosphate (TPhP)-induced neurodevelopmental toxicity. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 271, 115960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, I.; Barbosa, D.J.; Benfeito, S.; Silva, V.; Chavarria, D.; Borges, F.; Remião, F.; Silva, R. Molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis and their involvement in brain diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 244, 108373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Hansell, A.L.; Granell, R.; Blangiardo, M.; Zottoli, M.; Fecht, D.; Gulliver, J.; Henderson, A.J.; Elliott, P. Prenatal, Early-life and Childhood Exposure to Air Pollution and Lung Function: The ALSPAC Cohort. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, F.D.; Goes, T.C.; Vígaro, M.G.; Teixeira-Silva, F. Automation of the free-exploratory paradigm. J. Neurosci. Methods 2011, 197, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, N.; Yan, C.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Y.; Liu, C.; Gao, W.; Zhu, Y.; et al. TREM1 induces microglial ferroptosis through the PERK pathway in diabetic-associated cognitive impairment. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 383, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genes | Sequences (5′–3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| BDNF | Forward | GCCCATGAAAGAAGTAAACGTCC |

| Reverse | AGTGTCAGCCAGTGATGTCGTC | |

| PSD95 | Forward | TCACATTGGAAAGGGGTAA |

| Reverse | AAGATGGATGGGTCGTCA | |

| SYP | Forward | CTTCGGCGACTTCTACTACTTT |

| Reverse | GGAGCGGATGGATGTTTG | |

| SYN1 | Forward | CTTCTCGTCGCTGTCTAA |

| Reverse | ATGGATCTTCTTCCCTTT | |

| GPX4 | Forward | ATTCTCAGCCAAGGACAT |

| Reverse | ATGCCACAGGATTCCATACC | |

| SCL7A11 | Forward | TTGGAGCCCTGTCCTATGC |

| Reverse | CGAGCAGTTCCACCCAGACC | |

| TFR1 | Forward | GAGTGGCTACCTGGGCTAT |

| Reverse | TGTCTGTCTCCTCCGTTT | |

| ACSL4 | Forward | ACTTTCCACTTGTGACTTTAT |

| Reverse | CTTCAGTTTGCTTTCCAG | |

| IL-17 | Forward | ACTACCTCAACCGTTCCA |

| Reverse | GAGCTTCCCAGATCACAG | |

| IL-6 | Forward | TACCACTCCCAACAGACC |

| Reverse | TTTCCACGATTTCCCAGA | |

| TNF-α | Forward | GCGGTGCCTATGTCTCAG |

| Reverse | TCACCCCGAAGTTCAGTA | |

| INF-γ | Forward | AGCAACAACATAAGCGTC |

| Reverse | CTCAAACTTGGCAATACTC | |

| IL-8 | Forward | GGACACTTTCTTGCTTGC |

| Reverse | ATTACAGATTTATCCCCATT | |

| β-Actin | Forward | GTGCTATGTTGCTCTAGACTTCG |

| Reverse | ATGCCACAGGATTCCATACC |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, N.; Guo, X.; Su, Y.; Pan, M.; Lin, K.; Ma, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zeng, H. Gestational and Lactational Exposure to BPS Triggers Microglial Ferroptosis via the SLC7A11/GPX4 Antioxidant Axis and Induces Memory Impairment in Offspring Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411953

Xu N, Guo X, Su Y, Pan M, Lin K, Ma Z, Zhou H, Zeng H. Gestational and Lactational Exposure to BPS Triggers Microglial Ferroptosis via the SLC7A11/GPX4 Antioxidant Axis and Induces Memory Impairment in Offspring Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411953

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Nuo, Xinxin Guo, Yan Su, Mengfen Pan, Kaixing Lin, Zhensong Ma, Haozhe Zhou, and Huaicai Zeng. 2025. "Gestational and Lactational Exposure to BPS Triggers Microglial Ferroptosis via the SLC7A11/GPX4 Antioxidant Axis and Induces Memory Impairment in Offspring Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411953

APA StyleXu, N., Guo, X., Su, Y., Pan, M., Lin, K., Ma, Z., Zhou, H., & Zeng, H. (2025). Gestational and Lactational Exposure to BPS Triggers Microglial Ferroptosis via the SLC7A11/GPX4 Antioxidant Axis and Induces Memory Impairment in Offspring Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411953