T Regulatory Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Are They Major Players?

Abstract

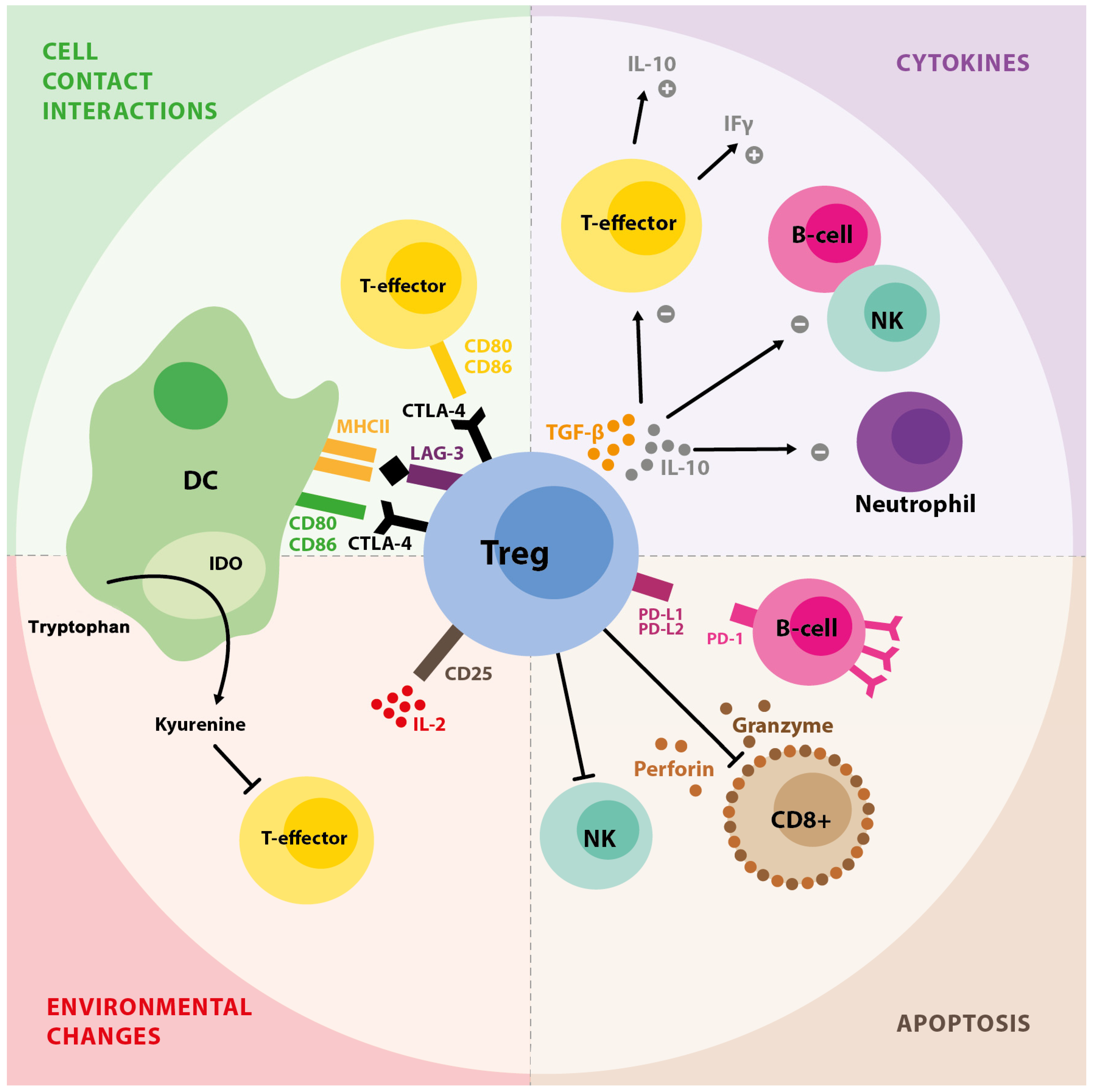

1. T Regulatory Cell Background

2. Tregs in Autoimmune Disorders

3. Tregs in IBD

3.1. Experimental Studies

3.2. Studies in Humans

3.3. Tregs-Based Therapy in IBD

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakaguchi, S.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nomura, T.; Ono, M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell 2008, 133, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L.; Christie, J.; Ramsdell, F.; Brunkow, M.E.; Ferguson, P.J.; Whitesell, L.; Kelly, T.E.; Saulsbury, F.T.; Chance, P.F.; Ochs, H.D. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 20–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildin, R.S.; Ramsdell, F.; Peake, J.; Faravelli, F.; Casanova, J.L.; Buist, N.; Levy-Lahad, E.; Mazzella, M.; Goulet, O.; Perroni, L.; et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat. Genet. 2001, 27, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakaguchi, S.; Sakaguchi, N.; Asano, M.; Itoh, M.; Toda, M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor α-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baecher-Allan, C.; Brown, J.A.; Freeman, G.J.; Hafler, D.A. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, S.; Nomura, T.; Sakaguchi, S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science 2003, 299, 1057–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieckmann, D.; Plottner, H.; Berchtold, S.; Berger, T.; Schuler, G. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 193, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefowicz, S.Z.; Rudensky, A. Control of regulatory T cell lineage commitment and maintenance. Immunity 2009, 30, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, C.; Carter, N. Is there a feudal hierarchy amongst regulatory immune cells? More than just Tregs. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Oberle, N.; Krammer, P.H. Molecular mechanisms of treg-mediated T cell suppression. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Tagami, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Uede, T.; Shimizu, J.; Sakaguchi, N.; Mak, T.W.; Sakaguchi, S. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.; Lelievre, J.D.; Carriere, M.; Bensussan, A.; Lévy, Y. Regulatory T cells differentially modulate the maturation and apoptosis of human CD8+ T-cell subsets. Blood 2009, 113, 4556–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iikuni, N.; Lourenço, E.V.; Hahn, B.H.; La Cava, A. Cutting edge: Regulatory T cells directly suppress B cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1518–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotot, J.; Dhana, E.; Yagita, H.; Kaiser, R.; Ludwig-Portugall, I.; Kurts, C. Antigen-specific Helios-, Neuropilin-1− Tregs induce apoptosis of autoreactive B cells via PD-L1. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2018, 96, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sojka, D.; Huang, Y.H.; Fowell, D. Mechanisms of regulatory T-cell suppression—A diverse arsenal for a moving target. Immunology 2008, 124, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.T.; Workman, C.; Flies, D.; Pan, X.; Marson, A.; Zhou, G.; Hipkiss, E.L.; Ravi, S.; Kowalski, J.; Levitsky, H.I.; et al. Role of LAG-3 in regulatory T cells. Immunity 2004, 21, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempkes, R.W.M.; Joosten, I.; Koenen, H.J.P.M.; He, X. Metabolic pathways involved in regulatory T cell functionality. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.G.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Gray, J.D.; Horwitz, D.A. IL-2 is essential for TGF-beta to convert naive CD4+CD25-cells to CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and for expansion of these cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 2018–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Stephan, S.; Bluestone, J.A. Peripherally induced Tregs—Role in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyss, L.; Stadinski, B.D.; King, C.G.; Schallenberg, S.; McCarthy, N.I.; Lee, J.Y.; Kretschmer, K.; Terracciano, L.M.; Aderson, G.; Surh, C.D.; et al. Affinity for self-antigen selects Treg cells with distinct functional properties. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1093–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevyrev, D.; Tereshchenko, V. Treg Heterogeneity, Function, and Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10, 3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Z. Inducing tolerance to pregnancy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1159–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, T.; Dhar, S.; Sa, G. Tumor-infiltrating T-regulatory cells adapt to altered metabolism to promote tumor-immune escape. Curr. Res. Immunol. 2021, 2, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.W. The Increasing Prevalence of Autoimmunity and Autoimmune Diseases: An Urgent Call to Action for Improved Understanding, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2022, 80, 102266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblum, M.D.; Remedios, K.A.; Abbas, A.K. Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2228–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere-Ortells, J.M.; Pérez-García, V.; Marín-Alberca, G.; Peris-Pertusa, A.; Benito, J.M.; Marco, F.M.; Zubcoff, J.J.; Navarro-Blasco, F.J. Quantification and phenotype of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis according to disease activity Score-28. Autoimmunity 2009, 42, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, C.A.; Brown, A.K.; Bejarano, V.; Douglas, S.H.; Burgoyne, C.H.; Greenstein, A.S.; Boylston, A.W.; Emery, P.; Ponchel, F.; Isaacs, J.D. Early rheumatoid arthritis is associated with a deficit in the CD4+CD25high regulatory T cell population in peripheral blood reactive. Rheumatology 2006, 45, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Z. A study on relationship among apoptosis rates, number of peripheral T cell subtypes and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2016, 19, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.M.; Baecher-Allan, C.; Hafler, D.A. Multiple sclerosis and regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Immunol. 2008, 28, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.M.; O’Neil-Andersen, N.J.; Zurier, R.B.; Lawrence, D.A. CD4+CD25high T cell numbers are enriched in the peripheral blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Immunol. 2008, 253, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourreza, E.; Shahbazi, M.; Mirzakhani, M.; Yousefghahari, B.; Akbari, R.; Oliaei, F.; Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, M. Increased frequency of activated regulatory T cells in patients with lupus nephritis. Hum. Immunol. 2022, 7, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczyńska, I.; Baskiewicz-Masiuk, M.; Ratajczek-Stefanska, V.; Seranow, K.; Maleszka, R.; Kurpisz, M.; Giedrys-Kalemba, S. CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells and CD4+CD69+ T cells in peripheral blood of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Centr. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 34, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayne, C.G.; Williams, C.B. Induced and Natural Regulatory T Cells in the Development of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2013, 19, 1772–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W.; Fuss, I.; Mannon, P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 117, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, F.; Martin, M.; Kesselring, R.; Schiechl, G.; Geissler, E.K.; Schlitt, H.J.; Fichtner-Feigl, S. Deletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in genetically targeted mice supports development of intestinal inflammation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 31, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hontecillas, R.; Bassaganya-Riera, J. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ Is Required for Regulatory CD4+ T Cell-Mediated Protection against Colitis. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 2940–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, S.M.; Staley, E.M.; Lorenz, R.G. Altered generation of induced regulatory T cells in the FVB.mdr1a|[minus]|/|[minus]| mouse model of colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2012, 6, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.B.; Aherne, C.M.; McNamee, E.N.; Lebsack, M.D.; Eltzschig, H.; Jedlicka, P.; Rivera-Nieves, J. Flt3 ligand expands CD103+ dendritic cells and FoxP3+ T regulatory cells, and attenuates Crohn’s-like murine ileitis. Gut 2012, 61, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powrie, F.; Leach, M.W.; Mauze, S.; Caddle, L.B.; Coffman, R.L. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C. B-17 scid mice. Int. Immunol. 1993, 5, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haribhai, D.; Lin, W.; Edwards, B.; Ziegelbauer, J.; Salzman, N.; Carlson, M.R.; Li, S.H.; Simpson, P.M.; Chatila, T.B.; Williams, C.B. A central role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance induction in experimental colitis. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 3461–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Saini, S.; Tandel, N.; Sahu, K.; Mishra, R.; Tyagi, R.K. Translating Treg Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Humanized Mice. Cells 2021, 10, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maul, J.; Loddenkemper, C.; Mundt, P.; Stallmach, A.; Zeitz, M.; Duchmann, R. Peripheral and intestinal regulatory CD4+ CD25(high) T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Nakamura, K.; Honda, K.; Kitamura, Y.; Mizutani, T.; Araki, Y.; Kabemura, T.; Chijiiwa, Y.; Harada, N.; Nawata, H. An inverse correlation of human peripheral blood regulatory T cell frequency with the disease activity of ulcerative colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2006, 51, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saruta, M.; Yu, Q.T.; Fleshner, P.R.; Mantel, P.-Y.; Schmidt-Weber, C.; Banham, A.H.; Papadakis, K.A. Characterization of FOXP3+CD4+ regulatory T cells in Crohn’s disease. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 125, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Fukunaga, K.; Fukuda, Y.; Tozawa, K.; Kamikozuru, K.; Ohnishi, K.; Kusaka, T.; Kosaka, T.; Hida, N.; Ohda, Y.; et al. Demonstration of low-regulatory CD25High+CD4+ and high-pro-inflammatory CD28-CD4+ T-Cell subsets in patients with ulcerative colitis: Modified by selective granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2007, 52, 2725–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamouard, P.; Monneaux, F.; Richert, Z.; Voegeli, A.C.; Lavaux, T.; Gaub, M.P.; Baumann, R.; Oudet, P.; Muller, S. Diminution of Circulating CD4+CD25 high T cells in naïve Crohn’s disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2009, 54, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamikozuru, K.; Fukunaga, K.; Hirota, S.; Hida, N.; Ohda, Y.; Yoshida, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Tozawa, K.; Kawa, K.; Iimuro, M.; et al. The expression profile of functional regulatory T cells, CD4+CD25high+/forkhead box protein P3+, in patients with ulcerative colitis during active and quiescent disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009, 156, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, G.; Nancey, S.; Sardi, F.; Roblin, X.; Flourié, B.; Kaiserlian, D. Therapy with anti-TNFalpha antibody enhances number and function of Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.P.; Zhao, Z.B.; Chen, J.H.; Yu, C.G. Expression of CD4+ forkhead box P3 (FOXP3)+ regulatory T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. J. Dig. Dis. 2011, 12, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, J.; Karczewski, M. Possible defect of regulatory T cells in patients with ulcerative colitis. Centr. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 36, 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, K.; Zhang, S.; Yao, J.; He, Y.; Chen, B.; Zeng, Z.; Zhong, B.; Chen, M. Imbalances of CD4(+) T-cell subgroups in Crohn’s disease and their relationship with disease activity and prognosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 29, 1808–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadnia-Afrouzi, M.; Zavaran Hosseini, A.; Khalili, A.; Abediankenari, S.; Hosseini, V.; Maleki, I. Decrease of CD4+ CD25+ CD127low FoxP3+ regulatory T cells with impaired suppressive function in untreated ulcerative colitis patients. Autoimmunity 2015, 48, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, N.; He, X.; Lu, A.; Wei, W.; Jiang, M. The Th17/Treg Immune Imbalance in Ulcerative Colitis Disease in a Chinese Han Population. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 7089137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.; Ebrahimpour, S.; Maleki, I.; Abediankenari, S.; Mohammadnia Afrouzi, M. CD4+CD25+CD127low FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in Crohn’s disease. Rom. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 56, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.R.; Xia, X.P.; Cai, X.N.; Hu, D.Y.; Shao, X.X.; Xia, S.L.; Jiang, Y. Association of Breg cells and Treg cells with the clinical effects of Infliximab in the treatment of Chinese patients with Crohn’s disease. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020, 100, 3303–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, L.; Felice, C.; Procoli, A.; Bonanno, G.; Martinelli, E.; Marzo, M.; Mocci, G.; Pugliese, D.; Andrisani, G.; Danese, S.; et al. FOXP3(+) T regulatory cell modifications in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with anti-TNFalpha agents. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 286368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sabatino, A.; Biancheri, P.; Piconese, S.; Rosado, M.M.; Ardizzone, S.; Rovedatti, L.; Ubezio, C.; Massari, A.; Sampietro, G.M.; Foschi, D.; et al. Peripheral regulatory T cells and serum transforming growth factor-beta: Relationship with clinical response to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Scaleia, R.; Morrone, S.; Stoppacciaro, A.; Scarpino, S.; Antonelli, M.; Bianchi, E.; Nardo, G.; Oliva, S.; Viola, F.; Cucchiara, S.; et al. Peripheral and intestinal CD4+ T cells with a regulatory phenotype in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 51, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznurkowska, K.; Żawrocki, A.; Sznurkowski, J.; Zieliński, M.; Landowski, P.; Plata-Nazar, K.; Iżycka-Świeszewska, E.; Trzonkowski, P.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A.; Kamińska, B. Peripheral and intestinal T-regulatory cells are upregulated in children with inflammatory bowel disease at onset of disease. Immunol. Investig. 2016, 45, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sznurkowska, K.; Luty, J.; Bryl, E.; Witkowski, J.; Hermann-Okoniewska, B.; Landowski, P.; Kosek, M.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A. Enhancement of Circulating and Intestinal T Regulatory Cells and Their Expression of Helios and Neuropilin-1 in Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Inflamm. Res. 2020, 26, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Strisciuglio, C.; Vitale, S.; Santopaolo, M.; Bruzzese, D.; Micillo, T.; Scarpato, E.; Miele, E.; Staiano, A.; Troncone, R.; et al. Increased frequency of regulatory T cells in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis: A compensative role? Pediatr. Res. 2020, 87, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Cao, Y.; Chen, P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Circulating and intestinal regulatory T cells in inflammatory bowel disease: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 43, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kugathasan, S.; Saubermann, L.J.; Smith, L.; Kou, D.; Itoh, J.; Binion, D.G.; Levine, A.D.; Blumberg, R.S.; Fiocchi, C. Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2006, 56, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makita, S.; Kanai, T.; Oshima, S.; Uraushihara, K.; Totsuka, T.; Sawada, T.; Nakamura, T.; Koganei, K.; Fukushima, T.; Watanabe, M. CD4+CD25bright T cells in human intestinal lamina propria as regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmén, N.; Lundgren, A.; Lundin, S.; Bergin, A.M.; Rudin, A.; Sjovall, H.; Ohman, L. Functional CD4+CD25highregulatory T cells are enriched in the colonic mucosa of patients with active ulcerative colitis and increase with disease activity. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2006, 12, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Arijs, I.; De Hertogh, G.; Vermeire, S.; Noman, M.; Bullens, D.; Coorevits, L.; Sagaert, X.; Schuit, F.; Rutgeerts, P.; et al. Reciprocal changes of Foxp3 expression in blood and intestinal mucosa in IBD patients responding to infliximab. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2010, 16, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reikvam, D.; Perminow, G.; Lyckander, L.; Gran, J.G.; Brandtzaeg, P.; Vatn, M.; Carlsen, H.S. Increase of regulatory T cells in ileal mucosa of untreated pediatric Crohn’s disease patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznurkowska, K.; Żawrocki, A.; Sznurkowski, J.; Iżycka-Świeszewska, E.; Landowski, P.; Szlagatys-Sidorkiewicz, A.; Plata-Nazar, K.; Kamińska, B. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and regulatory T cells in intestinal mucosa in children with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2017, 31, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlig, H.H.; Coombes, J.; Mottet, C.; Izcue, A.; Thompson, C.; Fanger, A.; Tannapfel, A.; Fontenot, J.D.; Ramsdell, F.; Powrie, F. Characterization of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ and IL-10-secreting CD4+CD25+ T cells during cure of colitis. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 5852–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsen, J.; Agnholt, J.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Rømer, J.L.; Hvas, C.L.; Dahlerup, J.F. FOXP3(+)CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties can be cultured from colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005, 141, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.T.; Saruta, M.; Avanesyan, A.; Fleshner, P.R.; Banham, A.H.; Papadakis, K.A. Expression and functional characterization of FOXP3+ CD4+ regulatory T cells in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2007, 13, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Park, Y.W.; Park, M.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Rhee, I. Regulatory T cells and their role in inflammatory bowel disease: Molecular targets, therapeutic strategies and translational advances. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 239, 117087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeppli, R.E.; Wu, D.; Cook, L.; Levings, M.K. The Environment of Regulatory T Cell Biology: Cytokines, Metabolites, and the Microbiome. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, E.R.; Lorenz, U.M. Breaking Free of Control: How Conventional T Cells Overcome Regulatory T Cell Suppression. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, A.; Long, S.A.; Cerosaletti, K.; Ni, C.T.; Samuels, P.; Kita, M.; Buckner, J.H. In active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, effector T cell resistance to adaptive T(regs) involves IL-6-mediated signaling. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 170ra15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Rieck, M.; Sanda, S.; Pihoker, C.; Greenbaum, C.; Buckner, J.H. The effector T cells of diabetic subjects are resistant to regulation via CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 7350–7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, A.M.; Shevach, E.M. Helios: Still Behind the Clouds. Immunology 2019, 158, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurek, E.; Cebula, A.; Wojciech, L.; Pietrzak, M.; Rempala, G.; Kisielow, P.; Ignatowicz, L. Differences in Expression Level of Helios and Neuropilin-1 do Not Distinguish Thymus-Derived From Extrathymically-Induced CD4+Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandwaskar, R.; Dalal, R.; Gupta, S.; Sharma, A.; Parashar, D.; Kashyap, V.K.; Sohal, J.S.; Tripathi, S.K. Dysregulation of T cell response in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Immunol. 2024, 100, e13412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Zhou, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liang, T.; Shi, L.; Long, J.; Yuan, D. Regulatory T Cell Plasticity and Stability and Autoimmune Diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluestone, J.A.; McKenzie, B.S.; Beilke, J.; Ramsdell, F. Opportunities for Treg cell therapy for the treatment of human disease. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1166135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek-Trzonkowska, N.; Myśliwiec, M.; Dobyszuk, A.; Grabowska, M.; Derkowska, I.; Juścińska, J.; Owczuk, R.; Szadkowska, A.; Witkowski, P.; Młynarski, W.; et al. Therapy of type 1 diabetes with CD4(+)CD25(high)CD127-regulatory T cells prolongs survival of pancreatic islets—Results of one year follow-up. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 153, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek-Trzonkowska, N.; Mysliwiec, M.; Dobyszuk, A.; Grabowska, M.; Techmanska, I.; Juscinska, J.; Wujtewicz, M.A.; Witkowski, P.; Mlynarski, W.; Balcerska, A.; et al. Administration of CD4+CD25highCD127-regulatory T cells preserves β-cell function in type 1 diabetes in children. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, 1817–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desreumaux, P.; Foussat, A.; Allez, M.; Beaugerie, L.; Hébuterne, X.; Bouhnik, Y.; Nachury, M.; Brun, V.; Bastian, H.; Belmonte, N.; et al. Safety and efficacy of antigen-specific regulatory T-cell therapy for patients with refractory Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1207–1217.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamo, T.; Hippen, K.L.; MacMillan, M.L.; Brunstein, C.G.; Miller, J.S.; Wagner, J.E.; Blazar, B.R.; McKenna, D.H. Regulatory T Cells: A Review of Manufacturing and Clinical Utility. Transfusion 2022, 62, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elinav, E.; Waks, T.; Eshhar, Z. Redirection of regulatory T cells with predetermined specificity for the treatment of experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 2014–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierini, A.; Iliopoulou, B.P.; Peiris, H.; Pérez-Cruz, M.; Baker, J.; Hsu, K.; Gu, X.; Zheng, P.-P.; Erkers, T.; Tang, S.-W.; et al. T Cells expressing chimeric antigen receptor promote immune tolerance. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e92865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication | Disease, Studied Population | Crucial Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Maul J. et al. (2005) [43] | Adults, N = 46, no information about previous treatment | Decreased number of peripheral blood Tregs in IBD patients, which increase during remission, lower in active disease. Proper function of circulating Tregs. |

| Takahashi M. et al. (2006) [44] | Adults, UC, previously treated | The number of peripheral blood Tregs lower in IBD patients than in HC, the number of Tregs inversely correlated with disease activity. |

| Saruta, M. et al. (2007) [45] | Adults, N = 30, CD, previously treated | The number of peripheral blood Tregs decreased and was inversely correlated with the activity of the disease. |

| Yokoyama Y et al. (2007) [46] | Adults, N = 23, UC, previously treated | Lower number of peripheral blood CD25High+CD4 lymphocytes compared to healthy controls, lower number in active compared to quiescent disease. |

| Chamouard P et al. (2009) [47] | Adults N = 85, CD/UC, naïve patients | The number of peripheral blood Tregs lower in IBD patients than in healthy controls. |

| Kamikozuru K et al. (2009) [48] | Adults = 31, UC, previously treated, non-responders | Decreased levels of Tregs in UC patients not responding to conventional therapy compared to healthy controls. |

| La Scaleia et al. (2010) [59] | Children, N = 43, UC/CD, naïve patients | Increased number of peripheral blood and intestinal Tregs in active disease. Normalization of intestinal Tregs in remission, peripheral Tregs remained increased. |

| Di Sabatino et al. (2010) [58] | Adults, N = 20, CD, previously treated | No significant difference between CD patients and healthy controls. Responders to infliximab presented higher rates of Tregs. |

| Boschetti G et al. (2011) [49] | Adults, N = 25, CU/CD, previously treated | The number of peripheral blood Tregs lower in IBD patients than in healthy controls, but it increased after anti TNFalpha therapy. |

| Wang Y et al. (2011) [50] | Adults, N = 139, UC/CD, previously treated | Decrease in CD4+FOXP3+ Treg cells in peripheral blood and an accumulation of Treg cells in inflamed mucosae. |

| Karczewski J et al. (2011) [51] | Adults, N = 40, UC, previously treated | Decreased frequency of peripheral blood Tregs compared to healthy controls. |

| Guidi L et al. (2013) [56] | Adults N = 32, UC and CD, previously treated | No difference in peripheral blood Tregs between IBD patients and healthy controls. |

| Chao K et al. (2014) [52] | Adults = 46, CD, not treated for 3 mths | Lower rate of peripheral blood Tregs in CD patients. |

| Mohammadnia-Afrouzi M et al. (2015) [53] | Adults, N = 32, UC, naïve patients | Decreased rate of peripheral blood Tregs in UC patients, inversely correlated with disease activity. |

| Sznurkowska K et al. (2016) [60] | Children; N = 24; UC/CD, UC, and CD; naïve patients | Increased number of peripheral blood and intestinal Tregs in naïve IBD patients. |

| Gong Y et al. (2016) [54] | Adults, N = 90, UC, treatment history not described | Decreased rate of peripheral blood Tregs in UC patients. |

| Khalili A et al. (2018) [55] | Adults, N = 23, CD | Decreased rate of peripheral blood Tregs in CD patients, proper Tregs, function. |

| Sznurkowska K et al. (2020) [61] | Children, N = 15, UC and CD, naïve patients | Increased number of intestinal and circulating Tregs, the rate of Tregs in bowel mucosae higher than in the blood. |

| Vitale A et al. (2020) [62] | Children, N = 35, UC/CD, naïve patients | Increased number of circulating and intestinal Tregs in naïve IBD patients. |

| Lin QR et al. (2020) [56] | Adults, N = 32, CD, previously treated | Decreased rate of peripheral blood g Tregs in CD patients before Infliximab therapy. |

| Publication | Disease, Studied Population | Crucial Findings, Method Used |

|---|---|---|

| Makita et al. (2004) [65] | Adults, N = 49, CU/CD, previously treated | Increased number of intestinal Tregs compared to healthy controls, proper function of Tregs isolated from colonic biopsies. Cytometry. |

| Maul J. et al. (2005) [43] | Adults, N = 46 (24 active disease), no information about previous treatment | Increased number of intestinal Tregs compared to healthy controls, but lower than in acute diverticulitis. Immunochemistry. |

| Holmen N et al. (2006) [66] | Adults, N = 39, UC, no information about previous treatment | Increased amounts of Tregs in inflamed mucosae, correlation with disease activity, proper function. Cytometry. |

| Saruta, M. et al. (2007) [45] | Adults, N = 30, CD previously treated | Inflamed mucosae enriched in Tregs, proper function ex vivo. Cytometry. |

| Li et al. (2010) [67] | Adults, N = 40, CU/CD, previously treated | Increased density of Tregs in inflamed mucosae. Immunochemistry. |

| Reikvam, D et al. (2011) [68] | Adults, N = 12, children, N = 14, CD naïve patients | Increased density of Tregs in inflamed mucosae. The number of Tregs higher in children than in adults. Immunochemistry. |

| Wang Y et al. (2011) [50] | Adults, N = 139, UC/CD, previously treated | Accumulation of Treg cells in inflamed mucosae. Immunochemistry. |

| K Sznurkowska et al. (2017) [69] | Children, N = 66, UC/CD Naïve patients | Increased density of Tregs in inflamed mucosae compared to IBS patients. Immunochemistry. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sznurkowska, K. T Regulatory Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Are They Major Players? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411944

Sznurkowska K. T Regulatory Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Are They Major Players? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411944

Chicago/Turabian StyleSznurkowska, Katarzyna. 2025. "T Regulatory Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Are They Major Players?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411944

APA StyleSznurkowska, K. (2025). T Regulatory Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Are They Major Players? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11944. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411944