Expression of New Gene Markers Regulating Protein Metabolism in Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

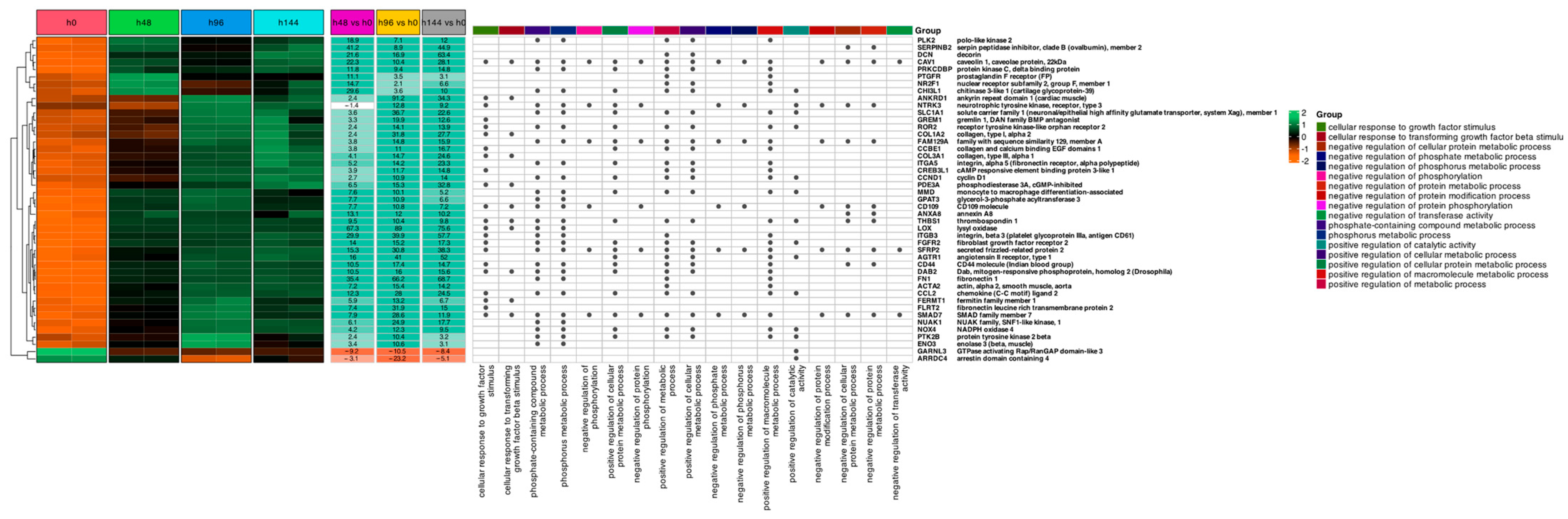

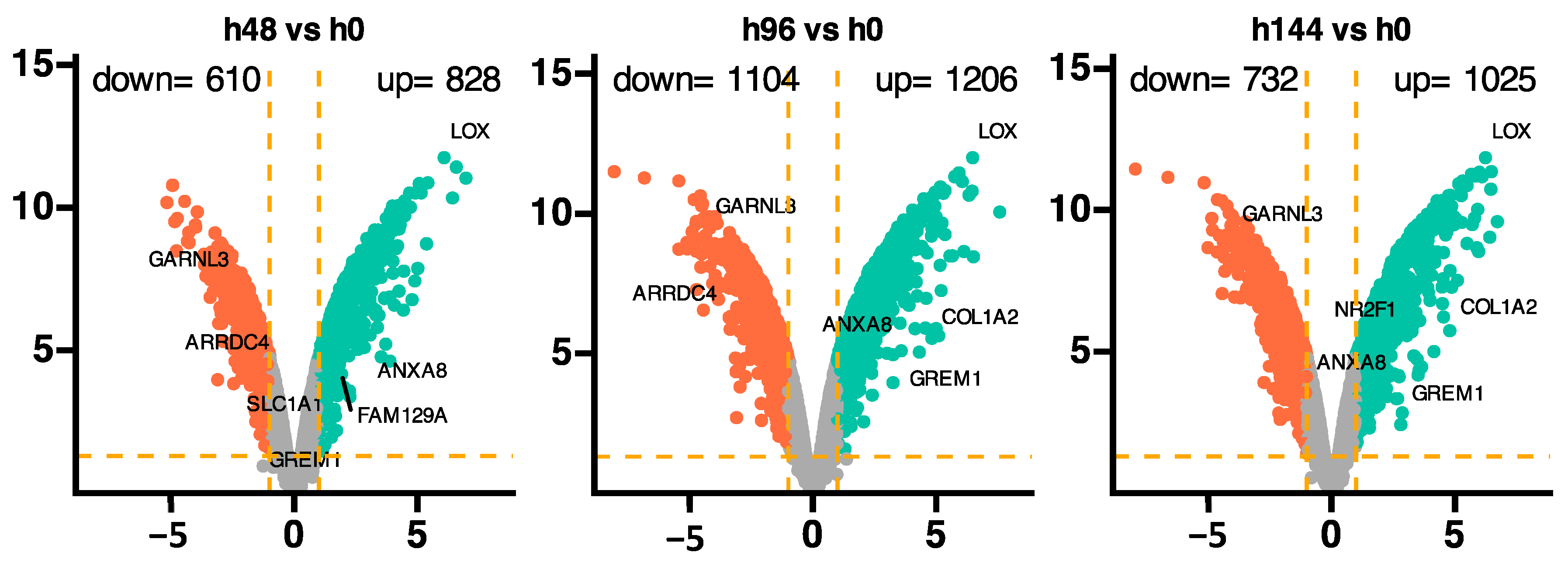

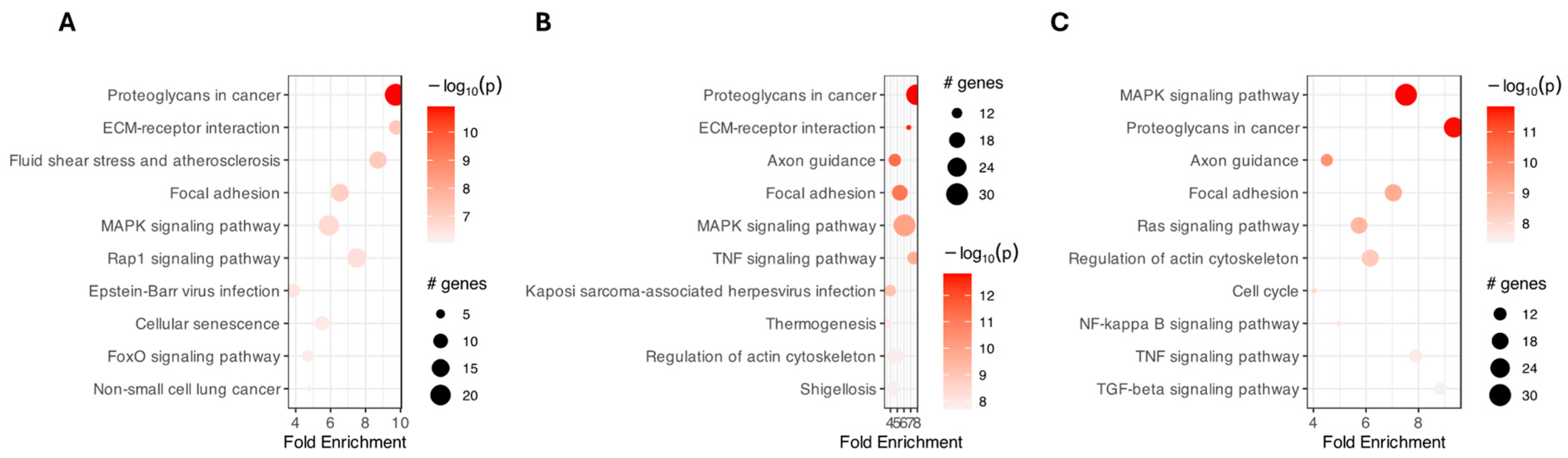

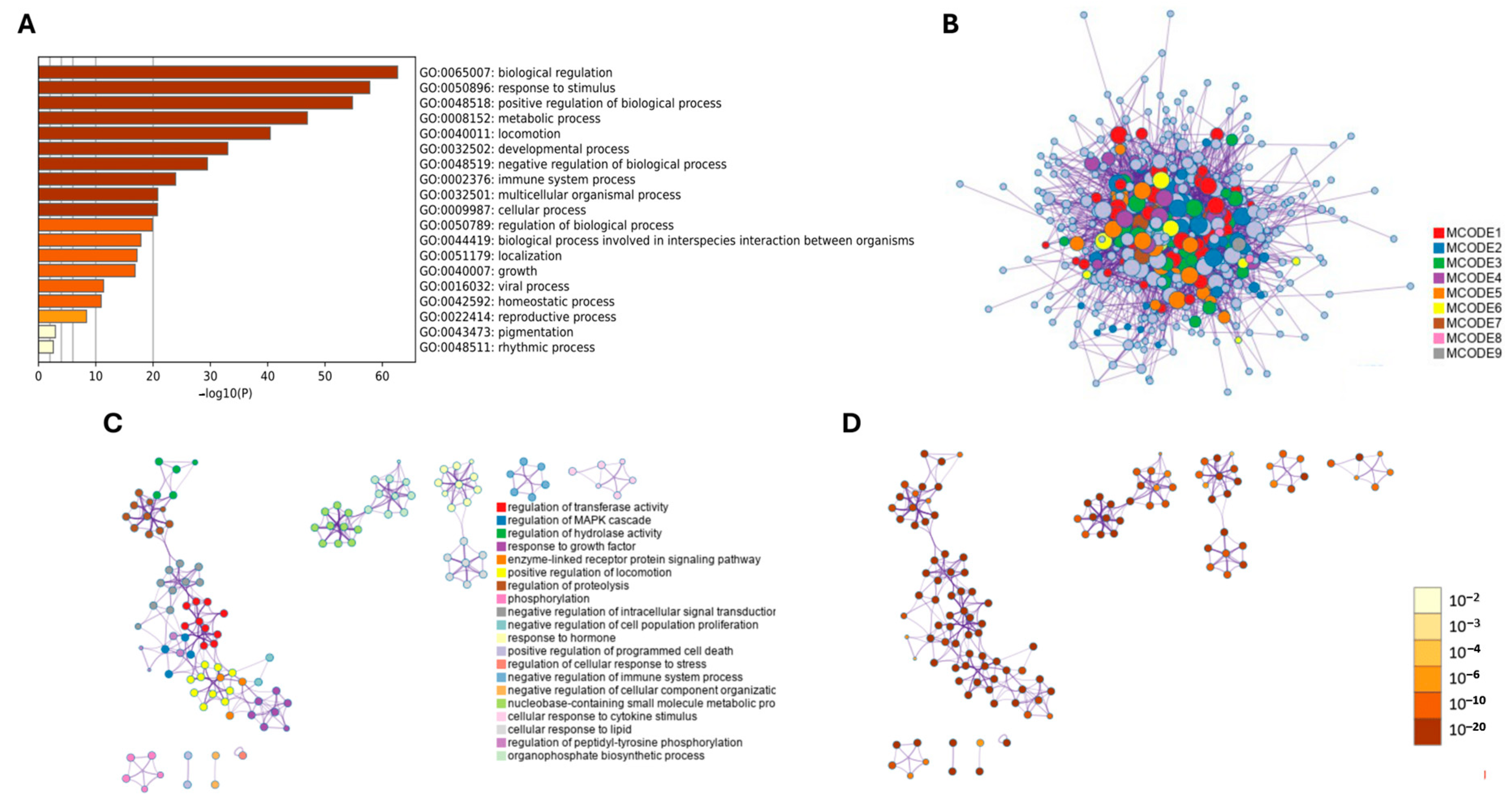

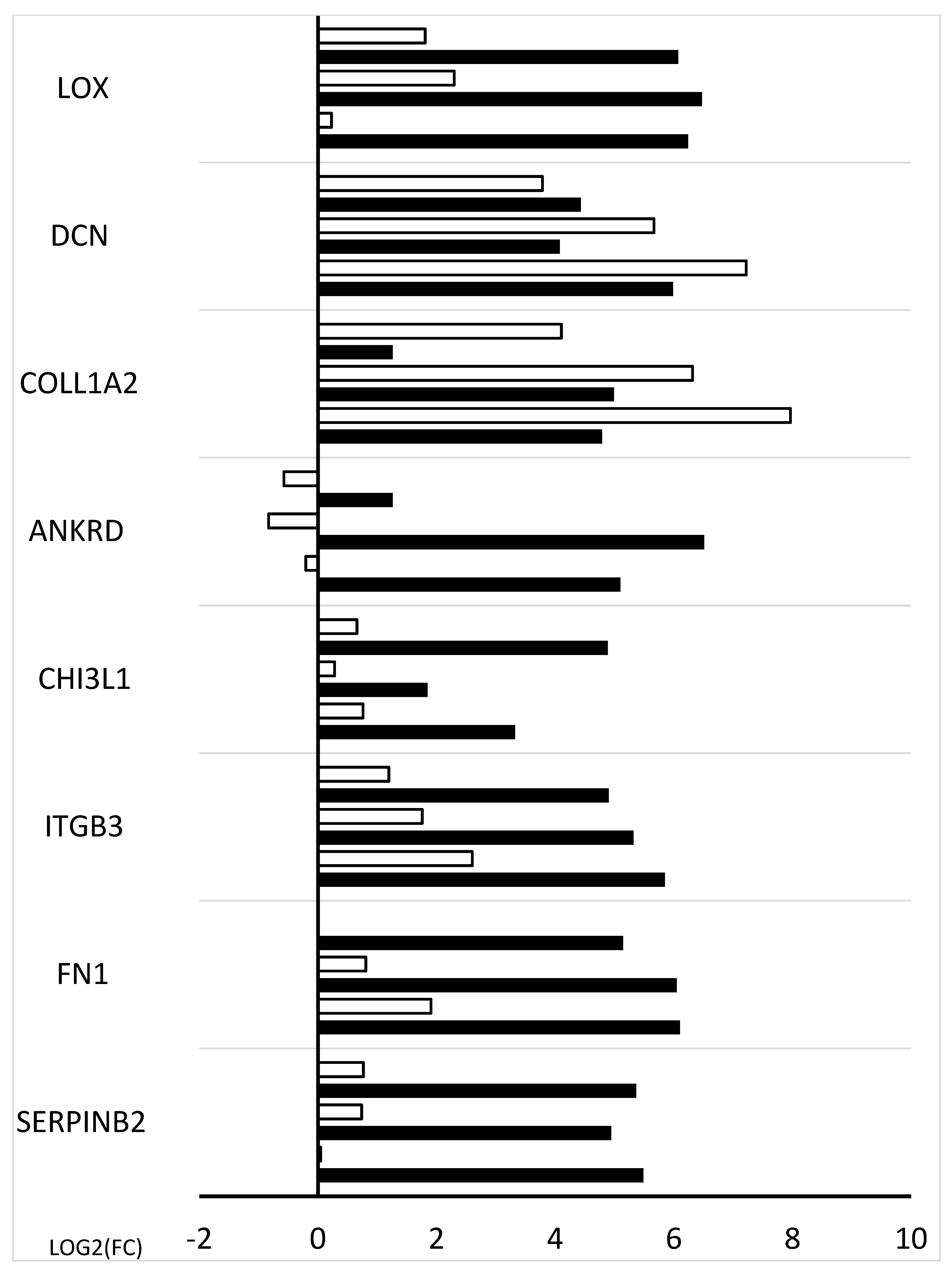

2. Results

3. Discussion

Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. RNA Isolation

4.2. Primers Design

4.3. Reverse Transcription

4.4. Microarray Validation

4.5. Microarray Data Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayes, E.; Winston, N.; Stocco, C. Molecular Crosstalk between Insulin-like Growth Factors and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone in the Regulation of Granulosa Cell Function. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2024, 23, e12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C. The Differentiation Fate of Granulosa Cells and the Regulatory Mechanism in Ovary. Reprod. Sci. 2024, 32, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jia, Y.; Meng, S.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Pan, Z. Mechanisms of and Potential Medications for Oxidative Stress in Ovarian Granulosa Cells: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Liu, D. The Function of Exosomes in Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2023, 394, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.R.; Barbalho, E.C.; Barrozo, L.G.; de Assis, E.I.T.; Costa, F.C.; Silva, J.R.V. The Mechanisms That Control the Preantral to Early Antral Follicle Transition and the Strategies to Have Efficient Culture Systems to Promote Their Growth in vitro. Zygote 2023, 31, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa-Aguirre, A.; Llamosas, R.; Dias, J.A. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Sweetness: How Carbohydrate Structures Impact on the Biological Function of the Hormone. Arch. Med. Res. 2024, 55, 103091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.-C.E.; Brink, G.J.; Poot, A.J.; Braat, A.J.A.T.; Jonges, G.N.; Zweemer, R.P. Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Expression and Its Potential Application for Theranostics in Subtypes of Ovarian Tumors: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.S.K.; Shikanov, A. Follicle Development as an Orchestrated Signaling Network in a 3D Organoid. J. Biol. Eng. 2019, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A.L.; Jaskiewicz, N.M.; Maucieri, A.M.; Townson, D.H. Stimulatory Effects of TGFα in Granulosa Cells of Bovine Small Antral Follicles. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, R.; Kyogoku, H.; Lee, J.; Miyano, T. Oocyte-Derived Growth Factors Promote Development of Antrum-like Structures by Porcine Cumulus Granulosa Cells in vitro. J. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 68, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, A.; Dunning, K.R.; Dinh, D.T.; Akison, L.K.; Robker, R.L.; Russell, D.L. Dynamic Regulation of Semaphorin 7A and Adhesion Receptors in Ovarian Follicle Remodeling and Ovulation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1261038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holesh, J.E.; Bass, A.N.; Lord, M. Physiology, Ovulation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-J.; Chao, Y.-Y.; Huang, W.-K.; Chang, W.-F.; Tzeng, C.-R.; Chuang, C.-H.; Lai, P.-L.; Schuyler, S.C.; Li, L.-Y.; Lu, J. Identification of Apelin/APJ Signaling Dysregulation in a Human iPSC-Derived Granulosa Cell Model of Turner Syndrome. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, H.M.; Mishina, T.; Hayashi, T.; Yoshimura, M.; Kuse, M.; Nikaido, I.; Kitajima, T.S. Transcriptomic Signatures of WNT-Driven Pathways and Granulosa Cell-Oocyte Interactions during Primordial Follicle Activation. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R.N.; Chakravarthi, V.P.; Ratri, A.; Hong, X.; Gossen, J.A.; Christenson, L.K. Granulosa Cell Specific Loss of Adar in Mice Delays Ovulation, Oocyte Maturation and Leads to Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulus, J.; Kulus, M.; Kranc, W.; Jopek, K.; Zdun, M.; Józkowiak, M.; Jaśkowski, J.M.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Bukowska, D.; Antosik, P.; et al. Transcriptomic Profile of New Gene Markers Encoding Proteins Responsible for Structure of Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Biology 2021, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Zhang, H.; Chang, H.-M.; Klausen, C.; Huang, H.-F.; Jin, M.; Leung, P.C.K. Activin A Promotes Hyaluronan Production and Upregulates Versican Expression in Human Granulosa Cells†. Biol. Reprod. 2022, 107, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, K.; Puttabyatappa, M.; Wynn, M.A.; Hannon, P.R.; Al-Alem, L.F.; Rosewell, K.L.; Akin, J.; Curry, T.E. Protease Expression in the Human and Rat Cumulus-Oocyte Complex during the Periovulatory Period: A Role in Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Migration. Biol. Reprod. 2024, 111, 845–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.S.; Lee, J.; Jun, J.H. Decorin: A Multifunctional Proteoglycan Involved in Oocyte Maturation and Trophoblast Migration. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2021, 48, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, M.E.; Irving-Rodgers, H.F.; Byers, S.; Rodgers, R.J. Identification and Immunolocalization of Decorin, Versican, Perlecan, Nidogen, and Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycans in Bovine Small-Antral Ovarian Follicles1. Biol. Reprod. 2000, 63, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, E.; Shibata, S.; Shibata, T.; Sasaki, H.; Singh, D.P. Role of Decorin in the Lens and Ocular Diseases. Cells 2022, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohto-Fujita, E.; Shimizu, M.; Atomi, A.; Hiruta, H.; Hosoda, R.; Horinouchi, S.; Miyazaki, S.; Murakami, T.; Asano, Y.; Hasebe, Y.; et al. Eggshell Membrane and Its Major Component Lysozyme and Ovotransferrin Enhance the Secretion of Decorin as an Endogenous Antifibrotic Mediator from Lung Fibroblasts and Ameliorate Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 39, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, S.; Yang, N.; Tan, R.P.; Moh, E.S.X.; Fu, L.; Packer, N.H.; Whitelock, J.M.; Wise, S.G.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J.; Lord, M.S. Tuning Recombinant Perlecan Domain V to Regulate Angiogenic Growth Factors and Enhance Endothelialization of Electrospun Silk Vascular Grafts. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, e2400855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, T.D.; Bang-Christensen, S.R.; Jørgensen, A.M.; Løppke, C.; Spliid, C.B.; Sand, N.T.; Clausen, T.M.; Salanti, A.; Agerbæk, M.Ø. The Role of Proteoglycans in Cancer Metastasis and Circulating Tumor Cell Analysis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati Zeppa, S.; Agostini, D.; Ferrini, F.; Gervasi, M.; Barbieri, E.; Bartolacci, A.; Piccoli, G.; Saltarelli, R.; Sestili, P.; Stocchi, V. Interventions on Gut Microbiota for Healthy Aging. Cells 2023, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.; Panitch, A. Proteoglycans and Proteoglycan Mimetics for Tissue Engineering. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C754–C761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanaka, S.; Shigetomi, H.; Kobayashi, H. Reprogramming of Glucose Metabolism of Cumulus Cells and Oocytes and Its Therapeutic Significance. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.-H.; Liu, X.-Y.; Wang, J. Essential Role of Granulosa Cell Glucose and Lipid Metabolism on Oocytes and the Potential Metabolic Imbalance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, K.; Gao, L.; Zhu, P.; Shu, L.; Cai, L.; Diao, F.; Mao, Y. Glucose Metabolism Disorder Related to Follicular Fluid Exosomal miR-122-5p in Cumulus Cells of Endometriosis Patients. Reprod. Camb. Engl. 2024, 168, e240028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, G.; Qin, X.; Mo, L.; Xiong, X.; Xiong, Y.; He, H.; Lan, D.; Fu, W.; Li, J.; et al. Molecular Characterization of MSX2 Gene and Its Role in Regulating Steroidogenesis in Yak (Bos grunniens) Cumulus Granulosa Cells. Theriogenology 2025, 231, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammad, A.; Ahmed, T.; Ullah, K.; Hu, L.; Luo, H.; Alphayo Kambey, P.; Faisal, S.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Vitamin C Alleviates the Negative Effects of Heat Stress on Reproductive Processes by Regulating Amino Acid Metabolism in Granulosa Cells. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Voorhis, B.J.; Dunn, M.S.; Falck, J.R.; Bhatt, R.K.; VanRollins, M.; Snyder, G.D. Metabolism of Arachidonic Acid to Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids by Human Granulosa Cells May Mediate Steroidogenesis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 76, 1555–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudon, M.; Ramé, C.; Price, C.; Dupont, J. Irisin Modulates Glucose Metabolism and Inhibits Steroidogenesis in Bovine Granulosa Cells. Reproduction 2023, 165, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, D.; Dimmer, E.; Huntley, R.; Barrell, D.; O’Donovan, C.; Apweiler, R. QuickGO: A Web-Based Tool for Gene Ontology Searching. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 3045–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packa, V.; Howell, T.; Bostan, V.; Furdui, V.I. Phosphorus-Based Metabolic Pathway Tracers in Surface Waters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 29498–29508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rauch, J.; Kolch, W. Targeting MAPK Signaling in Cancer: Mechanisms of Drug Resistance and Sensitivity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-J.; Pan, W.-W.; Liu, S.-B.; Shen, Z.-F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.-L. ERK/MAPK Signalling Pathway and Tumorigenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golikov, M.V.; Valuev-Elliston, V.T.; Smirnova, O.A.; Ivanov, A.V. Physiological Media in Studies of Cell Metabolism. Mol. Biol. 2022, 56, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, K.; Lee, H.J.; Na, K.-S.; Fernandes-Cunha, G.M.; Blanco, I.J.; Djalilian, A.; Myung, D. Characterizing the Impact of 2D and 3D Culture Conditions on the Therapeutic Effects of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome on Corneal Wound Healing in vitro and Ex Vivo. Acta Biomater. 2019, 99, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golkar-Narenji, A.; Antosik, P.; Nolin, S.; Rucinski, M.; Jopek, K.; Zok, A.; Sobolewski, J.; Jankowski, M.; Zdun, M.; Bukowska, D.; et al. Gene Ontology Groups and Signaling Pathways Regulating the Process of Avian Satellite Cell Differentiation. Genes 2022, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, J.; Martínková, S.; Petr, J.; Žalmanová, T.; Trnka, J. Metabolic Cooperation in the Ovarian Follicle. Physiol. Res. 2020, 69, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, D.D.; Gentile, R.; Sallicandro, L.; Biagini, A.; Quellari, P.T.; Gliozheni, E.; Sabbatini, P.; Ragonese, F.; Malvasi, A.; D’Amato, A.; et al. Electro-Metabolic Coupling of Cumulus–Oocyte Complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, G.S.; Carvalho, K.C.; Ferreira, C.d.S.; Alvarez, P.A.C.; Monteleone, P.A.A.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares, J.M. Granulosa Cells and Follicular Development: A Brief Review. Rev. Assoc. Médica Bras. 2023, 69, e20230175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.A.; Rizos, D.; Rodriguez-Martinez, H.; Funahashi, H. Oocyte-Cumulus Cells Crosstalk: New Comparative Insights. Theriogenology 2023, 205, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Yu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, T.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X. Jiawei Qingxin Zishen Decoction mitigates granulosa cell apoptosis and enhances ovarian reserve through Netrin/UNC5B signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2026, 355, 120686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.H.; Miyano, T. Interaction between Growing Oocytes and Granulosa Cells in vitro. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2019, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelcer, E.; Komarowska, H.; Jopek, K.; Żok, A.; Iżycki, D.; Malińska, A.; Szczepaniak, B.; Komekbai, Z.; Karczewski, M.; Wierzbicki, T.; et al. Biological Response of Adrenal Carcinoma and Melanoma Cells to Mitotane Treatment. Oncol. Lett. 2022, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strączyńska, P.; Papis, K.; Morawiec, E.; Czerwiński, M.; Gajewski, Z.; Olejek, A.; Bednarska-Czerwińska, A. Signaling Mechanisms and Their Regulation during in Vivo or in vitro Maturation of Mammalian Oocytes. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharti, D.; Jang, S.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-L.; Rho, G.-J. In vitro Generation of Oocyte Like Cells and Their In Vivo Efficacy: How Far We Have Been Succeeded. Cells 2020, 9, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, M.; Zok, A.; Guidolin, D.; De Caro, R.; Malendowicz, L.K. Expression of Precerebellins in Cultured Rat Calvaria Osteoblast-like Cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 22, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.-Z.; Luo, J.-R.; Cheng, S.-J.; Meng, X.-P.; Li, J.-Y.; Luo, S.-Y.; Zhong, Z.-H.; Jiang, X.-C.; Wang, X.; Ji, Y.-Q.; et al. GARNL3 Identified as a Crucial Target for Overcoming Temozolomide Resistance in EGFRvIII-Positive Glioblastoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 1550–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherfils, J. Small GTPase Signaling Hubs at the Surface of Cellular Membranes in Physiology and Disease. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Chang, H.-M.; Zhu, Y.-M.; Leung, P.C.K. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 Increases Lysyl Oxidase Activity via Up-Regulation of Snail in Human Granulosa-Lutein Cells. Cell. Signal. 2019, 53, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chang, H.-M.; Cheng, J.-C.; Klausen, C.; Leung, P.C.K.; Yang, X. Transforming Growth Factor-Β1 Increases Lysyl Oxidase Expression by Downregulating MIR29A in Human Granulosa Lutein Cells. Reproduction 2016, 152, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laczko, R.; Csiszar, K. Lysyl Oxidase (LOX): Functional Contributions to Signaling Pathways. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Ye, X. The Prognostic and Immune Infiltration Role of ITGB Superfamily Members in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2022, 14, 6445–6466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Budna, J.; Chachuła, A.; Kaźmierczak, D.; Rybska, M.; Ciesiółka, S.; Bryja, A.; Kranc, W.; Borys, S.; Żok, A.; Bukowska, D.; et al. Morphogenesis-Related Gene-Expression Profile in Porcine Oocytes before and after in vitro Maturation. Zygote 2017, 25, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, W.A.; Hirata, T.D.; Le, T.T.; Gardner, J.; Boyle, G.M.; Ellis, J.; Nakayama, E.; Pathirana, D.; Nakaya, H.I.; Suhrbier, A. SerpinB2 Inhibits Migration and Promotes a Resolution Phase Signature in Large Peritoneal Macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Guo, S.; Yan, L.; Zhu, H.; Li, H.; Shi, Z. TNFα-Erk1/2 Signaling Pathway-Regulated SerpinE1 and SerpinB2 Are Involved in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Porcine Granulosa Cell Proliferation. Cell. Signal. 2020, 73, 109702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Gao, J.; Pan, X.; Tang, Q.; Long, H.; Liu, Z. YKL-40 Knockdown Decreases Oxidative Stress Damage in Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2024, 28, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puttabyatappa, M.; Guo, X.; Dou, J.; Dumesic, D.; Bakulski, K.M.; Padmanabhan, V. Developmental Programming: Sheep Granulosa and Theca Cell–Specific Transcriptional Regulation by Prenatal Testosterone. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Henderson, B.R.; Emmanuel, C.; Harnett, P.R.; deFazio, A. Inhibition of ANKRD1 Sensitizes Human Ovarian Cancer Cells to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Apoptosis. Oncogene 2015, 34, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Wu, P.; Fan, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Xu, X. Identification of Candidate Genes Simultaneously Shared by Adipogenesis and Osteoblastogenesis from Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Folia Histochem. Cytobiol. 2022, 60, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Li, K.; Sun, B.; Xu, D.; Tong, L.; Yin, H.; Liao, Y.; Song, H.; Wang, T.; Jing, B.; et al. Dysregulated Glutamate Transporter SLC1A1 Propels Cystine Uptake via Xc− for Glutathione Synthesis in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2021, 81, 552–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.-H.; Zhang, F.-F.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Fang, K.-F.; Sun, W.-X.; Kong, N.; Wu, M.; Liu, H.-O.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; et al. Follicle Stimulating Hormone Controls Granulosa Cell Glutamine Synthesis to Regulate Ovulation. Protein Cell 2024, 15, 512–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Fu, Y.; Li, B.; Cheng, J.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Li, H. TGF-Β1 Induces Type I Collagen Deposition in Granulosa Cells via the AKT/GSK-3β Signaling Pathway-Mediated MMP1 down-Regulation. Reprod. Biol. 2022, 22, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, S.; Xu, S.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, M.; Pan, Q.; Huang, J. Granulosa Cells Improved Mare Oocyte Cytoplasmic Maturation by Providing Collagens. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 914735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Smith, L.R.; Khandekar, G.; Patel, P.; Yu, C.K.; Zhang, K.; Chen, C.S.; Han, L.; Wells, R.G. Distinct Effects of Different Matrix Proteoglycans on Collagen Fibrillogenesis and Cell-Mediated Collagen Reorganization. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, M.; Saller, S.; Ströbl, S.; Hennebold, J.D.; Dissen, G.A.; Ojeda, S.R.; Stouffer, R.L.; Berg, D.; Berg, U.; Mayerhofer, A. Decorin Is a Part of the Ovarian Extracellular Matrix in Primates and May Act as a Signaling Molecule. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 3249–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kedem, A.; Ulanenko-Shenkar, K.; Yung, Y.; Yerushalmi, G.M.; Maman, E.; Hourvitz, A. Elucidating Decorin’s Role in the Preovulatory Follicle. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaniker, E.J.; Babayev, E.; Duncan, F.E. Common Mechanisms of Physiological and Pathological Rupture Events in Biology: Novel Insights into Mammalian Ovulation and Beyond. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2023, 98, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, P.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Wu, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Feng, Y.; Guo, Z.; et al. A New Three-Dimensional Glass Scaffold Increases the in vitro Maturation Efficiency of Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) Oocyte via Remodelling the Extracellular Matrix and Cell Connection of Cumulus Cells. Reprod. Domest. Anim. Zuchthyg. 2020, 55, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, T.; Du, X.; Tao, Z.; Li, G.; Zhong, S.; Wen, J.; Zhou, C.; Xu, X. Transcriptome Analyses of Potential Regulators of Pre- and Post-Ovulatory Follicles in the Pigeon (Columba livia). Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2022, 34, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, X.; Bi, F.; Xiang, H.; Wang, N.; Gao, W.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Li, Y.; Huan, Y. Fibronectin 1 Supports Oocyte in vitro Maturation in Pigs. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, D.; Zeng, B.; Wang, T.; Chen, B.-L.; Li, D.-Y.; Li, Z.-J. Single Nucleus/Cell RNA-Seq of the Chicken Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Offers New Insights into the Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of Ovarian Development. Zool. Res. 2024, 45, 1088–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulus, J.; Kranc, W.; Kulus, M.; Bukowska, D.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Mozdziak, P.; Kempisty, B.; Antosik, P. New Gene Markers of Exosomal Regulation Are Involved in Porcine Granulosa Cell Adhesion, Migration, and Proliferation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowwarote, N.; Chahlaoui, Z.; Petit, S.; Duong, L.T.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Chansaenroj, A.; Kornsuthisopon, C.; Osathanon, T.; Ferre, F.C.; et al. Decellularized Extracellular Matrix Derived from Dental Pulp Stem Cells Promotes Gingival Fibroblast Adhesion and Migration. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeze, G.G.; Wu, L.; Alemu, B.K.; Lee, W.F.; Fung, L.W.Y.; Cheung, E.C.W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, C.C. Proteomics Approach to Discovering Non-Invasive Diagnostic Biomarkers and Understanding the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z. The Signaling Pathways Involved in Ovarian Follicle Development. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 730196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Qin, Q.-Y.; Qu, J.-X.; Wang, H.-Y.; Yan, J. Where Are the Theca Cells from: The Mechanism of Theca Cells Derivation and Differentiation. Chin. Med. J. 2020, 133, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feugang, J.M.; Ishak, G.M.; Eggert, M.W.; Arnold, R.D.; Rivers, O.S.; Willard, S.T.; Ryan, P.L.; Gastal, E.L. Intrafollicular Injection of Nanomolecules for Advancing Knowledge on Folliculogenesis in Livestock. Theriogenology 2022, 192, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkovskaya, A.; Buffone, A.; Žídek, M.; Weaver, V.M. Proteoglycans as Mediators of Cancer Tissue Mechanics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 569377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Yin, H. Zearalenone Induces Apoptosis and Cytoprotective Autophagy in Chicken Granulosa Cells by PI3K-AKT-mTOR and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Toxins 2021, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ke, Y.; Qiu, P.; Gao, J.; Deng, G. LncRNA NEAT1 Inhibits Apoptosis and Autophagy of Ovarian Granulosa Cells through miR-654/STC2-Mediated MAPK Signaling Pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 424, 113473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lin, J.; Chen, C.; Nie, X.; Dou, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Gong, Z. MicroRNA-146b-5p Overexpression Attenuates Premature Ovarian Failure in Mice by Inhibiting the Dab2ip/Ask1/P38-Mapk Pathway and γH2A.X Phosphorylation. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e12954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.-Y.; Liu, Z.; Shimada, M.; Sterneck, E.; Johnson, P.F.; Hedrick, S.M.; Richards, J.S. MAPK3/1 (ERK1/2) in Ovarian Granulosa Cells Are Essential for Female Fertility. Science 2009, 324, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, M.; Wu, N.; Liu, B.; Liu, Q.; Fan, X. TGF-β/Smads Signaling Pathway, Hippo-YAP/TAZ Signaling Pathway, and VEGF: Their Mechanisms and Roles in Vascular Remodeling Related Diseases. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2023, 11, e1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.A.; Perego, M.C.; Schütz, L.F.; Hemple, A.M.; Spicer, L.J. Hormonal Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGFA) Gene Expression in Granulosa and Theca Cells of Cattle1. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 97, 3034–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.; Brännström, M.; Akins, J.W.; Curry, T.E. New Insights into the Ovulatory Process in the Human Ovary. Hum. Reprod. Update 2025, 31, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Peña, A.A.; Petrik, J.J.; Hardy, D.B.; Holloway, A.C. Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol Increases Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Secretion through a Cyclooxygenase-Dependent Mechanism in Rat Granulosa Cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2022, 111, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Gong, S.; Zi, X.; Tan, Y. Effects of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) on the Viability, Apoptosis and Steroidogenesis of Yak (Bos Grunniens) Granulosa Cells. Theriogenology 2023, 207, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Chang, H.-M.; Yi, Y.; Yan, Y.; Thakur, A.; Leung, P.C.K.; Cheng, J.-C.; et al. TGF-Β1 Induces VEGF Expression in Human Granulosa-Lutein Cells: A Potential Mechanism for the Pathogenesis of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silveira, J.C.; Andrade, G.M.; Simas, R.C.; Martins-Júnior, H.A.; Eberlin, M.N.; Smith, L.C.; Perecin, F.; Meirelles, F.V. Lipid Profile of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Relationship with Bovine Oocyte Developmental Competence: New Players in Intra Follicular Cell Communication. Theriogenology 2021, 174, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, C.; Wyse, B.A.; Tsang, B.K.; Librach, C.L. Extracellular Vesicles and Their Content in the Context of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Endometriosis: A Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider, A.P.; Gomes, R.S.; Summers, A.F.; Tenley, S.C.; Abedal-Majed, M.A.; McFee, R.M.; Wood, J.R.; Davis, J.S.; Cupp, A.S. Identification of Lipids and Cytokines in Plasma and Follicular Fluid before and after Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Stimulation as Potential Markers for Follicular Maturation in Cattle. Animals 2023, 13, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lazo, L.; Brisard, D.; Elis, S.; Maillard, V.; Uzbekov, R.; Labas, V.; Desmarchais, A.; Papillier, P.; Monget, P.; Uzbekova, S. Fatty Acid Synthesis and Oxidation in Cumulus Cells Support Oocyte Maturation in Bovine. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 1502–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Andrade Melo-Sterza, F.; Poehland, R. Lipid Metabolism in Bovine Oocytes and Early Embryos under In Vivo, In vitro, and Stress Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vireque, A.A.; Tata, A.; Belaz, K.R.A.; Grázia, J.G.V.; Santos, F.N.; Arnold, D.R.; Basso, A.C.; Eberlin, M.N.; Silva-de-Sá, M.F.; Ferriani, R.A.; et al. MALDI Mass Spectrometry Reveals That Cumulus Cells Modulate the Lipid Profile of in vitro-Matured Bovine Oocytes. Syst. Biol. Reprod. Med. 2017, 63, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Shuangshuang, G.; Jianning, Y.; Zhendan, S. Systemic Analysis of Gene Expression Profiles in Porcine Granulosa Cells during Aging. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 96588–96603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranc, W.; Brązert, M.; Budna, J.; Celichowski, P.; Bryja, A.; Nawrocki, M.J.; Ożegowska, K.; Jankowski, M.; Chermuła, B.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska, M.; et al. Genes Responsible for Proliferation, Differentiation, and Junction Adhesion Are Significantly up-Regulated in Human Ovarian Granulosa Cells during a Long-Term Primary in vitro Culture. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 151, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Abreu, R.; Penalva, L.O.; Marcotte, E.M.; Vogel, C. Global signatures of protein and mRNA expression levels. Mol. Biosyst. 2009, 5, 1512–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynski, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-Step Method of RNA Isolation by Acid Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform Extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.W.; Amode, M.R.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barba, M.; Barnes, I.; Becker, A.; Bennett, R.; Berry, A.; Bhai, J.; et al. Ensembl 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D891–D899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautier, L.; Cope, L.; Bolstad, B.; Irizarry, R. Affy-Analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip Data at the Probe Level. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A.; Mundt, F. Factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses; R Package Version 1.0.7. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=factoextra (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Dennis, G.; Sherman, B.T.; Hosack, D.A.; Yang, J.; Gao, W.; Lane, H.C.; Lempicki, R.A. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003, 4, P3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamini, Y.; Cohen, R. Weighted False Discovery Rate Controlling Procedures for Clinical Trials. Biostatistics 2017, 18, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex Heatmaps Reveal Patterns and Correlations in Multidimensional Genomic Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goesmann, A.; Haubrock, M.; Meyer, F.; Kalinowski, J.; Giegerich, R. PathFinder: Reconstruction and Dynamic Visualization of Metabolic Pathways. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, B.; Pache, L.; Chang, M.; Khodabakhshi, A.H.; Tanaseichuk, O.; Benner, C.; Chanda, S.K. Metascape Provides a Biologist-Oriented Resource for the Analysis of Systems-Level Datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.D.; Hogue, C.W. An Automated Method for Finding Molecular Complexes in Large Protein Interaction Networks. BMC Bioinform. 2003, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Product Size (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOX | F | GTACAACCTGAGATGCGCTG | 208 |

| R | GCTGAATTCGTCCATGCTGT | ||

| DCN | F | CTCTCTGGCCAACACTCCTC | 155 |

| R | GCGGGCAGAAGTCATTAGAG | ||

| COLL1A2 | F | GTCAGACTGGTCCTGCTGGT | 163 |

| R | GTCAGACTGGTCCTGCTGGT | ||

| ANKRD | F | CTGCTTGAGGTGGGGAAGTA | 178 |

| R | GTGTCTCACTGTCTGGGGAA | ||

| CHI3L1 | F | GGATGCAAGTTCCGACAGAT | 202 |

| R | GAGGATCCCTTTCTCCTTGG | ||

| ITGB3 | F | GGATGCAAGTTCCGACAGAT | 175 |

| R | AGTCCTTTTCCGAGCACTCA | ||

| FN1 | F | TGAGCCTGAAGAGACCTGCT | 113 |

| R | CAGCTCCAATGCAGGTACAG | ||

| SERPINB2 | F | GGAAGAATACATTCGACTCTCCA | 170 |

| R | TGGTCTCCGCATCTACAGAA | ||

| ACTB | F | CCCTTGCCGCTCCGCCTTC | 156 |

| R | GCAGCAATATCGGTCATCCAT | ||

| GAPDH | F | CCAGAACATCATCCCTGCCT | 185 |

| R | CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG | ||

| HPRT | F | CCATCACATCGTAGCCCTC | 166 |

| R | ACTTTTATATCGCCCGTTGAC | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Data, K.; Kranc, W.; Blatkiewicz, M.; Domagała, D.; Niebora, J.; Chmielewski, P.P.; Bryja, A.; Berdowska, I.; Żok, A.; Kulus, M.; et al. Expression of New Gene Markers Regulating Protein Metabolism in Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411942

Data K, Kranc W, Blatkiewicz M, Domagała D, Niebora J, Chmielewski PP, Bryja A, Berdowska I, Żok A, Kulus M, et al. Expression of New Gene Markers Regulating Protein Metabolism in Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411942

Chicago/Turabian StyleData, Krzysztof, Wiesława Kranc, Małgorzata Blatkiewicz, Dominika Domagała, Julia Niebora, Piotr P. Chmielewski, Artur Bryja, Izabela Berdowska, Agnieszka Żok, Magdalena Kulus, and et al. 2025. "Expression of New Gene Markers Regulating Protein Metabolism in Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells In Vitro" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411942

APA StyleData, K., Kranc, W., Blatkiewicz, M., Domagała, D., Niebora, J., Chmielewski, P. P., Bryja, A., Berdowska, I., Żok, A., Kulus, M., Kulus, J., Wysocka, T., Spaczyński, R. Z., Piotrowska-Kempisty, H., Mozdziak, P., Kempisty, B., Antosik, P., Bukowska, D., & Skowroński, M. T. (2025). Expression of New Gene Markers Regulating Protein Metabolism in Porcine Ovarian Granulosa Cells In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11942. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411942