St. John’s Wort for Depression: From Neurotransmitters to Membrane Plasticity

Abstract

1. On the Origin of Depression: Integrating Psychosocial and Biological Perspectives

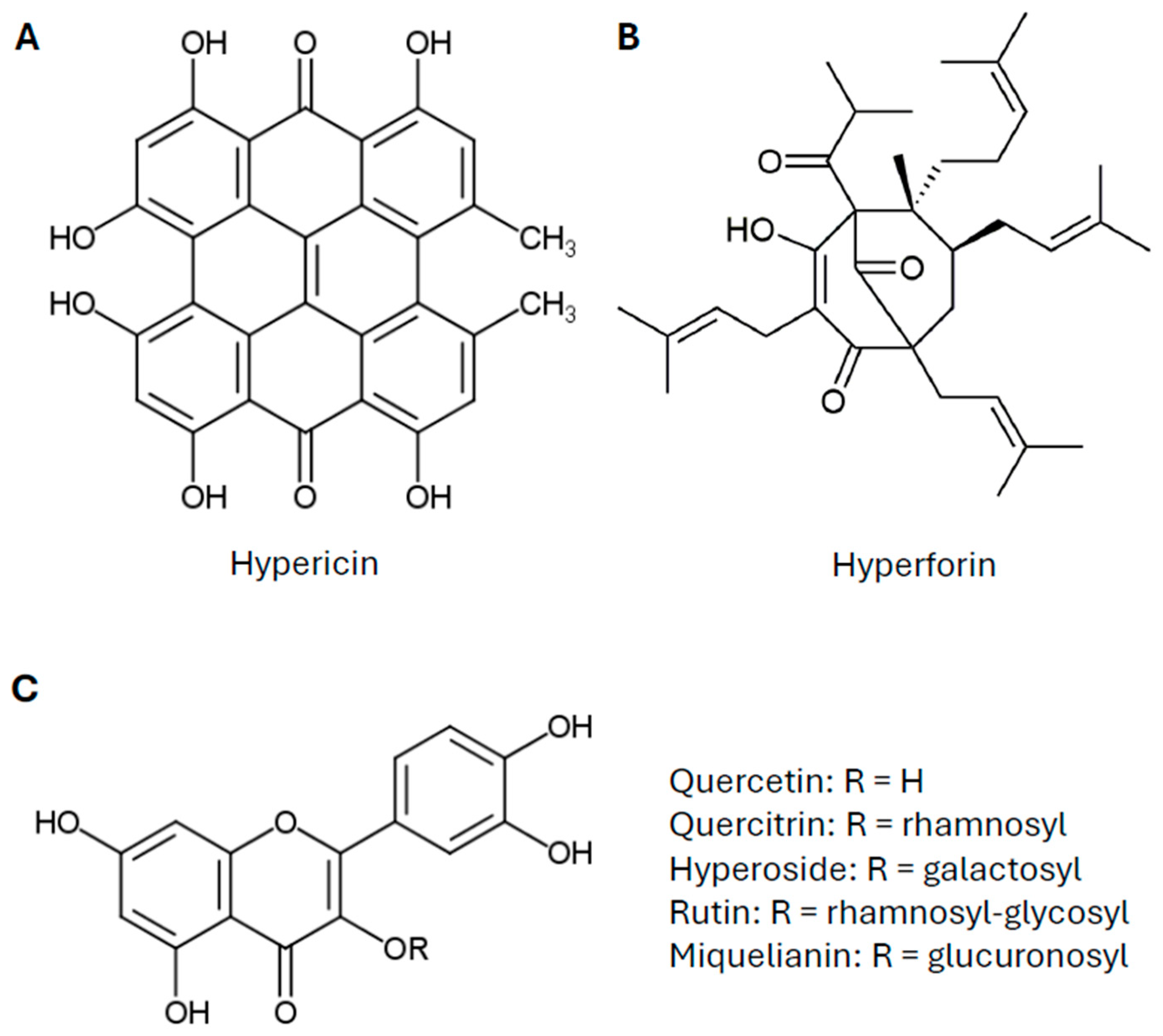

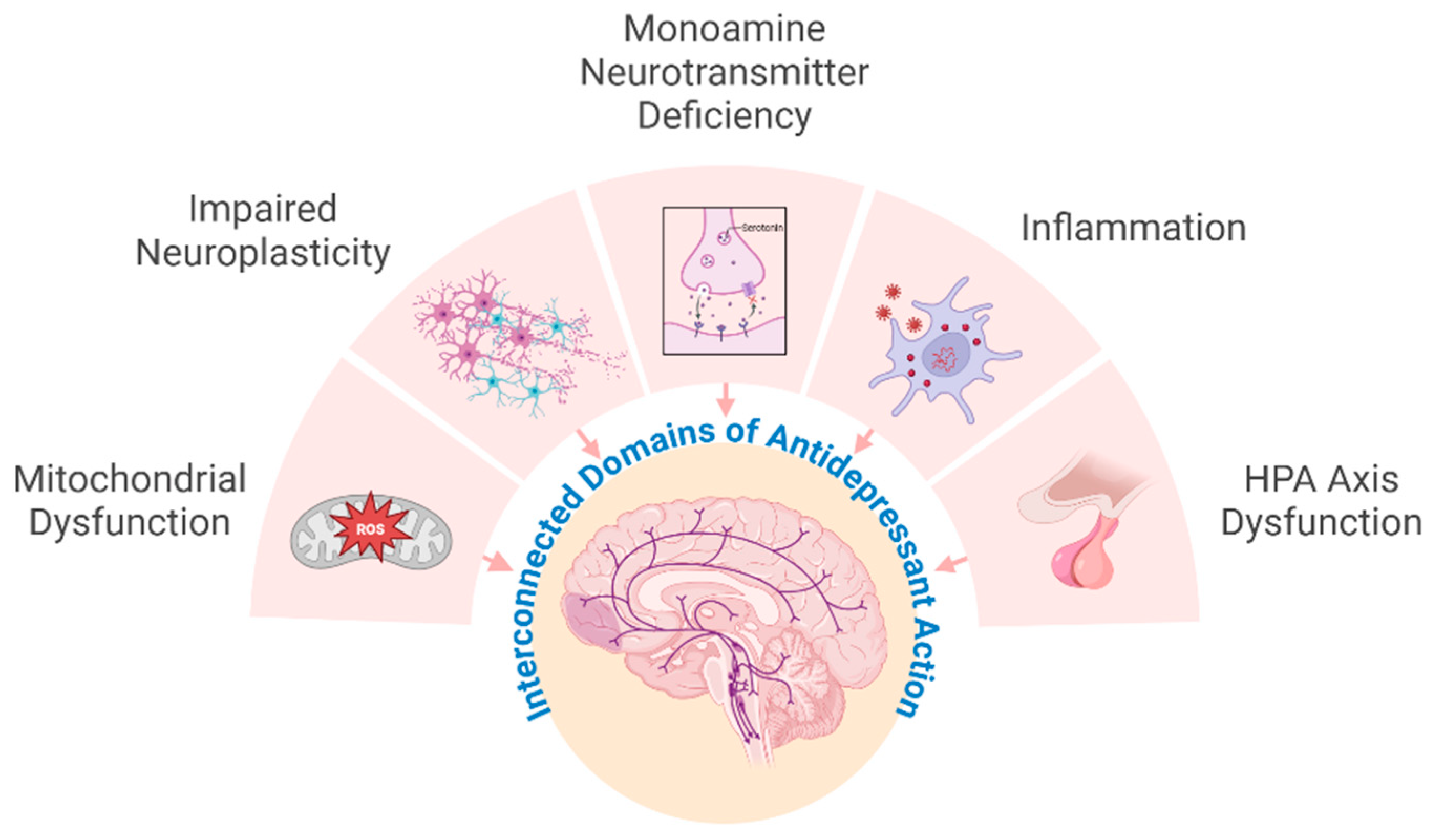

2. St. John’s Wort: A Traditional Antidepressant—From Historical Use to Clinical Evidence

3. Current Concepts in the Mechanisms of Antidepressants and St. John’s Wort

4. Beyond Synaptic Neurotransmission: The Role of Brain Lipids in Antidepressant Efficacy

5. St. John’s Wort and Membrane Plasticity: Bridging Classical Neurotransmission and Novel Mechanisms

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-HT1A | Serotonin 1A receptor |

| ACTH | Adrenocorticotropic hormone |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CE | Cholesteryl esters |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CRH | Corticotropin releasing hormone |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| CYP450 | Cytochrome P450 |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| EMA | European Medical Agency |

| FKBP5 | FK506 binding protein 5 |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| HMPC | Herbal Medicinal Products Committee |

| HPA | Hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LPEs | Lysophosphatidylethanolamines |

| mTORC1 | Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| PC | Phosphatidylcholine |

| PC-O | Phosphatidylcholine ethers |

| PE | Phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PS | Phosphatidylserine |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PXR | Pregnane-x-receptor |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCD1 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 |

| SJW | St John’s wort |

| SSRI | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| TAG | Triacylglycerols |

| TCAs | Tricyclic antidepressants |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| TrkB | Tropomyosin receptor kinase B |

| TRPC6 | Transient receptor potential canonical 6 |

References

- Dean, J.; Keshavan, M. The Neurobiology of Depression: An Integrated View. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 27, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major Depressive Disorder: Hypothesis, Mechanism, Prevention and Treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filatova, E.V.; Shadrina, M.I.; Slominsky, P.A. Major Depression: One Brain, One Disease, One Set of Intertwined Processes. Cells 2021, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, S. Mourning and Melancholia. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume Xiv (1914–1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works; The Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1917; pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T. The Evolution of the Cognitive Model of Depression and Its Neurobiological Correlates. Am. J. Psychiatry 2008, 165, 969–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, A.G.; Moos, R.H. Psychosocial Theory and Research on Depression: An Integrative Framework and Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1982, 2, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.F.; Neale, M.C.; Kendler, K.S. Genetic Epidemiology of Major Depression: Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. Psychiatr. Publ. 2000, 157, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, R.M. History and Evolution of the Monoamine Hypothesis of Depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2000, 61, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pastis, I.M.; Santos, G.; Paruchuri, A. Exploring the Role of Inflammation in Major Depressive Disorder: Beyond the Monoamine Hypothesis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1282242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindmarch, I. Expanding the Horizons of Depression: Beyond the Monoamine Hypothesis. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2001, 16, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartt, A.N.; Mariani, M.B.; Hen, R.; Mann, J.J.; Boldrini, M. Dysregulation of Adult Hippocampal Neuroplasticity in Major Depression: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Implications. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2689–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yirmiya, R. The Inflammatory Underpinning of Depression: An Historical Perspective. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 122, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, L.N.; Kuhlman, K.R.; Robles, T.F.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Craske, M.G.; Bower, J.E. The Role of Inflammation in Core Features of Depression: Insights from Paradigms Using Exogenously-Induced Inflammation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 94, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Derry, H.M.; Fagundes, C.P. Inflammation: Depression Fans the Flames and Feasts on the Heat. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.H.; Raison, C.L. The Role of Inflammation in Depression: From Evolutionary Imperative to Modern Treatment Target. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.; Lightman, S. The Human Stress Response. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, V.A.; Mercer, E.M.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Arrieta, M.C. Evolutionary Significance of the Neuroendocrine Stress Axis on Vertebrate Immunity and the Influence of the Microbiome on Early-Life Stress Regulation and Health Outcomes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The Hpa Axis in Major Depression: Classical Theories and New Developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuipers, S.D.; Bramham, C.R.; Cameron, H.A.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Korosi, A.; Lucassen, P.J. Environmental Control of Adult Neurogenesis: From Hippocampal Homeostasis to Behavior and Disease. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 808643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerry, J.D.; Hastings, P.D. In Search of Hpa Axis Dysregulation in Child and Adolescent Depression. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanson, N.K.; Herman, J.P.; Sakai, R.R.; Krause, E.G. Nongenomic Actions of Adrenal Steroids in the Central Nervous System. J. Neuroendocr. 2010, 22, 846–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, J.T.; Kuriyan, J. Molecular Mechanisms in Signal Transduction at the Membrane. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandam, L.S.; Brazel, M.; Zhou, M.; Jhaveri, D.J. Cortisol and Major Depressive Disorder-Translating Findings from Humans to Animal Models and Back. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, R.; Santana, M.M.; Aveleira, C.A.; Simoes, C.; Maciel, E.; Melo, T.; Santinha, D.; Oliveira, M.M.; Peixoto, F.; Domingues, P.; et al. Alterations in Phospholipidomic Profile in the Brain of Mouse Model of Depression Induced by Chronic Unpredictable Stress. Neuroscience 2014, 273, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Oliveira, T.G. Lipids under Stress—A Lipidomic Approach for the Study of Mood Disorders. Bioessays 2015, 37, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donoso, F.; Schverer, M.; Rea, K.; Pusceddu, M.M.; Roy, B.L.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Schellekens, H. Neurobiological Effects of Phospholipids in Vitro: Relevance to Stress-Related Disorders. Neurobiol. Stress 2020, 13, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Michaelis, E.K. Selective Neuronal Vulnerability to Oxidative Stress in the Brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhivaki, D.; Kagan, J.C. Innate Immune Detection of Lipid Oxidation as a Threat Assessment Strategy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Hezghia, A.; Shaikh, S.R.; Cenido, J.F.; Stark, R.E.; Mann, J.J.; Sublette, M.E. Regulation of Monoamine Transporters and Receptors by Lipid Microdomains: Implications for Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 2165–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschek, W. Wichtl—Teedrogen Und Phytopharmaka; Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, R.; Gloning, T. (Eds.) Hildegard Von Bingen: Physica. Liber Subtilitatum Diversarum Naturarum Creaturarum; Textkritische Ausgabe. 2 Bde; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, G. (Ed.) Das Lorscher Arzneibuch; (Handschrift Msc. Med. 1 der Staatsbibliothek Bamberg); Band 2: Übersetzung von Ulrich Stoll und Gundolf Keil Unter Mitwirkung von Altabt Albert Ohlmeyer; Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft: Stuttgart, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Butterweck, V.; Schmidt, M. St. John’s Wort: Role of Active Compounds for Its Mechanism of Action and Efficacy. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2007, 157, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linde, K.; Berner, M.M.; Kriston, L. St John’s Wort for Major Depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2008, 2008, CD000448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, S.; Caraci, F.; Forti, B.; Drago, F.; Aguglia, E. Efficacy and Tolerability of Hypericum Extract for the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 20, 747–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, U.I.; Büschel, B.; Kirch, W. Unwanted Pregnancy on Self-Medication with St John’s Wort Despite Hormonal Contraception. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Q.Y.; Bergquist, C.; Gerden, B. Safety of St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum). Lancet 2000, 355, 576–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johne, A.; Brockmöller, J.; Bauer, S.; Maurer, A.; Langheinrich, M.; Roots, I. Pharmacokinetic Interaction of Digoxin with an Herbal Extract from St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum). Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 66, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolussi, S.; Drewe, J.; Butterweck, V.; zu Schwabedissen, H.E.M. Clinical Relevance of St. John’s Wort Drug Interactions Revisited. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 1212–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.; Price, A. The Effect of Cytochrome P450 Metabolism on Drug Response, Interactions, and Adverse Effects. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 76, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, L.B.; Goodwin, B.; Jones, S.A.; Wisely, B.G.; Serabjit-Singh, C.J.; Willson, T.M.; Collins, J.L.; Kliewer, S.A. St. John’s Wort Induces Hepatic Drug Metabolism through Activation of the Pregnane X Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7500–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahner, C.; Kruttschnitt, E.; Uricher, J.; Lissy, M.; Hirsch, M.; Nicolussi, S.; Krahenbuhl, S.; Drewe, J. No Clinically Relevant Interactions of St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 Low in Hyperforin with Cytochrome P450 Enzymes and P-Glycoprotein. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 106, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Will-Shahab, L.; Bauer, S.; Kunter, U.; Roots, I.; Brattstrom, A. St John’s Wort Extract (Ze 117) Does Not Alter the Pharmacokinetics of a Low-Dose Oral Contraceptive. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S. Effect of St John’s Wort Dose and Preparations on the Pharmacokinetics of Digoxin. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 75, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.M.; Potterat, O.; Seibert, I.; Fertig, O.; zu Schwabedissen, H.E.M. Hyperforin-Induced Activation of the Pregnane X Receptor Is Influenced by the Organic Anion-Transporting Polypeptide 2b1. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 95, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Izzo, A.A. Herb-Drug Interactions with St John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): An Update on Clinical Observations. AAPS J. 2009, 11, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Assessment Report on Hypericum perforatum L., Herba; EMA/HMPC/244315/2016; Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC): Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen, N.; Damkier, P.; Pedersen, S.A. Serotonin Syndrome-a Focused Review. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 133, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmer, C.J.; Duman, R.S.; Cowen, P.J. How Do Antidepressants Work? New Perspectives for Refining Future Treatment Approaches. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkholm, C.; Monteggia, L.M. Bdnf—A Key Transducer of Antidepressant Effects. Neuropharmacology 2016, 102, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapia-Arancibia, L.; Rage, F.; Givalois, L.; Arancibia, S. Physiology of Bdnf: Focus on Hypothalamic Function. Front. Neuroendocr. 2004, 25, 77–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H. Synaptic Plasticity and Depression: New Insights from Stress and Rapid-Acting Antidepressants. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Butterweck, V. The Mechanisms of Action of St. John’s Wort: An Update. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. (1946) 2015, 165, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.S.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Wonnemann, M.; Singer, A.; Müller, W.E. Hyperforin as a Possible Antidepressant Component of Hypericum Extracts. Life Sci. 1998, 63, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, W.E.; Singer, A.; Wonnemann, M.; Hafner, U.; Rolli, M.; Schäfer, C. Hyperforin Represents the Neurotransmitter Reuptake Inhibiting Constituent of Hypericum Extract. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998, 31, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neary, J.T.; Bu, Y. Hypericum Li 160 Inhibits Uptake of Serotonin and Norepinephrine in Astrocytes. Brain Res. 1999, 816, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovic, S.; Müller, W.E. Pharmacological Profile of Hypericum Extract. Effect on Serotonin Uptake by Postsynaptic Receptors. Arzneim. Forsch. 1995, 45, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Ruedeberg, C.; Wiesmann, U.N.; Brattstroem, A.; Honegger, U.E. Hypericum perforatum L. (St John’s Wort) Extract Ze 117 Inhibits Dopamine Re-Uptake in Rat Striatal Brain Slices. An Implication for Use in Smoking Cessation Treatment? Phytother. Res. PTR 2010, 24, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonnemann, M.; Singer, A.; Siebert, B.; Müller, W.E. Evaluation of Synaptosomal Uptake Inhibition of Most Relevant Constituents of St. John’s Wort. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001, 34, 148–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, A.; Wonnemann, M.; Müller, W.E. Hyperforin, a Major Antidepressant Constituent of St. John’s Wort, Inhibits Serotonin Uptake by Elevating Free Intracellular Na+1. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999, 290, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M.; Valle, F.D.; Ciapparelli, C.; Diomede, L.; Morazzoni, P.; Verotta, L.; Caccia, S.; Cervo, L.; Mennini, T. Hypericum perforatum L. Extract Does Not Inhibit 5-Ht Transporter in Rat Brain Cortex. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1999, 360, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterweck, V.; Böckers, T.; Korte, B.; Wittkowski, W.; Winterhoff, H. Long-Term Effects of St. John’s Wort and Hypericin on Monoamine Levels in Rat Hypothalamus and Hippocampus. Brain Res. 2002, 930, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baureithel, K.H.; Büter, K.B.; Engesser, A.; Burkard, W.; Schaffner, W. Inhibition of Benzodiazepine Binding in Vitro by Amentoflavone, a Constituent of Various Species of Hypericum. Pharm. Acta Helv. 1997, 72, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cott, J.M. In Vitro Receptor Binding and Enzyme Inhibition by Hypericum perforatum Extract. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997, 30 (Suppl. S2), 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterweck, V.; Nahrstedt, A.; Evans, J.; Hufeisen, S.; Rauser, L.; Savage, J.; Popadak, B.; Ernsberger, P.; Roth, B.L. In Vitro Receptor Screening of Pure Constituents of St. John’s Wort Reveals Novel Interactions with a Number of Gpcrs. Psychopharmacology 2002, 162, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, M.; Moia, M.; Pirona, L.; Morizzoni, P.; Mennini, T. In Vitro Binding Studies with Two Hypericum perforatum Extracts--Hyperforin, Hypericin and Biapigenin--on 5-Ht6, 5-Ht7, Gaba(a)/Benzodiazepine, Sigma, Npy-Y1/Y2 Receptors and Dopamine Transporters. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001, 34 (Suppl. S1), S45–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, W.E.; Schäfer, C. Johanniskraut: In-Vitro Studie Über Hypericum-Extrakt (Li 160), Hypericin Und Kämpferol Als Antidepressiva. Dtsch. Apoth. Ztg. 1996, 136, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rolli, M.; Schäfer, C.; Müller, W.E. Effect of Hypericum Extract (Li 160) on Neurotransmitter Receptor Binding and Synaptosomal Uptake Systems. Pharmacopsychiatry 1995, 28, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Simmen, U.; Higelin, J.; Berger-Büter, K.; Schaffner, W.; Lundstrom, K. Neurochemical Studies with St. John’s Wort in Vitro. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001, 34 (Suppl. S1), S137–S142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirz, A.; Simmen, U.; Heilmann, J.; Calis, I.; Meier, B.; Sticher, O. Bisanthraquinone Glycosides of Hypericum perforatum with Binding Inhibition to Crh-1 Receptors. Phytochemistry 2000, 55, 941–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonnemann, M.; Schafer, C.; Müller, W.E. Effects of Hypericum Extracts on Glutaminergic and Gabaergic Receptor Systems. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997, 30, 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kientsch, U.; Bürgi, S.; Ruedeberg, S.C.; Probst, S.; Honegger, U.E. St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 (Hypericum perforatum) Inhibits Norepinephrine and Serotonin Uptake into Rat Brain Slices and Reduces ß-Adrenoceptor Numbers on Cultured Rat Brain Cells. Pharmacopsychiatry 2001, 34 (Suppl. S1), S56–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbrey, K.; Winterhoff, H.; Butterweck, V. Extracts of St. John’s Wort and Various Constituents Affect Beta-Adrenergic Binding in Rat Frontal Cortex. Life Sci. 2004, 74, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, W.E.; Rolli, M.; Schäfer, C.; Hafner, U. Effects of Hypericum Extract (Li 160) in Biochemical Models of Antidepressant Activity. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997, 30 (Suppl. S2), 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterweck, V.; Winterhoff, H.; Herkenham, M. St John’s Wort, Hypericin, and Imipramine: A Comparative Analysis of Mrna Levels in Brain Areas Involved in Hpa Axis Control Following Short-Term and Long-Term Administration in Normal and Stressed Rats. Mol. Psychiatry 2001, 6, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valvassori, S.S.; Borges, C.; Bavaresco, D.V.; Varela, R.B.; Resende, W.R.; Peterle, B.R.; Arent, C.O.; Budni, J.; Quevedo, J. Hypericum perforatum Chronic Treatment Affects Cognitive Parameters and Brain Neurotrophic Factor Levels. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2018, 40, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterweck, V.; Winterhoff, H.; Herkenham, M. Hyperforin-Containing Extracts of St John’s Wort Fail to Alter Gene Transcription in Brain Areas Involved in Hpa Axis Control in a Long-Term Treatment Regimen in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verjee, S.; Weston, A.; Kolb, C.; Kalbhenn-Aziz, H.; Butterweck, V. Hyperforin and Miquelianin from St. john’s Wort Attenuate Gene Expression in Neuronal Cells after Dexamethasone-Induced Stress. Planta Med. 2018, 84, 696–703. [Google Scholar]

- Menke, A. Is the Hpa Axis as Target for Depression Outdated, or Is There a New Hope? Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, B.; Brink, I.; Ploch, M. Modulation of Cytokine Expression by Hypericum Extract. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 1994, 7 (Suppl. S1), S60–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaterra, G.A.; Schwendler, A.; Huther, J.; Schwarzbach, H.; Schwarz, A.; Kolb, C.; Abdel-Aziz, H.; Kinscherf, R. Neurotrophic, Cytoprotective, and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of St. John’s Wort Extract on Differentiated Mouse Hippocampal Ht-22 Neurons. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Beffy, P.; Menegazzi, M.; De Tata, V.; Martino, L.; Sgarbossa, A.; Porozov, S.; Pippa, A.; Masini, M.; Marchetti, P.; et al. St. John’s Wort Extract and Hyperforin Protect Rat and Human Pancreatic Islets against Cytokine Toxicity. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, M.S.; Cardoso, R.D.; Fattori, V.; Arakawa, N.S.; Tomaz, J.C.; Lopes, N.P.; Casagrande, R.; Verri, W.A., Jr. Hypericum perforatum Reduces Paracetamol-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Lethality in Mice by Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. Phytother. Res. 2015, 29, 1097–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jungke, P.; Ostrow, G.; Li, J.L.; Norton, S.; Nieber, K.; Kelber, O.; Butterweck, V. Profiling of Hypothalamic and Hippocampal Gene Expression in Chronically Stressed Rats Treated with St. John’s Wort Extract (Stw 3-Vi) and Fluoxetine. Psychopharmacology 2011, 213, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hamdaoui, Y.; Zheng, F.; Fritz, N.; Ye, L.; Tran, M.A.; Schwickert, K.; Schirmeister, T.; Braeuning, A.; Lichtenstein, D.; Hellmich, U.A.; et al. Analysis of Hyperforin (St. John’s Wort) Action at Trpc6 Channel Leads to the Development of a New Class of Antidepressant Drugs. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 5070–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterweck, V.; Wall, A.; Liefländer-Wulf, U.; Winterhoff, H.; Nahrstedt, A. Effects of the Total Extract and Fractions of Hypericum perforatum in Animal Assays for Antidepressant Activity. Pharmacopsychiatry 1997, 30 (Suppl. S2), 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterweck, V.; Petereit, F.; Winterhoff, H.; Nahrstedt, A. Solubilized Hypericin and Pseudohypericin from Hypericum perforatum Exert Antidepressant Activity in the Forced Swimming Test. Planta Med. 1998, 64, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterweck, V.; Jürgenliemk, G.; Nahrstedt, A.; Winterhoff, H. Flavonoids from Hypericum perforatum Show Antidepressant Activity in the Forced Swimming Test. Planta Med. 2000, 66, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vry, J.; Maurel, S.; Schreiber, R.; de Beun, R.; Jentzsch, K.R. Comparison of Hypericum Extracts with Imipramine and Fluoxetine in Animal Models of Depression and Alcoholism. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999, 9, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.K.; Chakrabarti, A.; Chatterjee, S.S. Activity Profiles of Two Hyperforin-Containing Hypericum Extracts in Behavioral Models. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998, 31 (Suppl. S1), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarana, C.; Ghiglieri, O.; Taddei, I.; Tagliamonte, A.; De Montis, M.G. Imipramine and Fluoxetine Prevent the Stress-Induced Escape Deficits in Rats through a Distinct Mechanism of Action. Behav. Pharmacol. 1995, 6, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambarana, C.; Masi, F.; Tagliamonte, A.; Scheggi, S.; Ghiglieri, O.; De Montis, M.G. A Chronic Stress That Impairs Reactivity in Rats Also Decreases Dopaminergic Transmission in the Nucleus Accumbens: A Microdialysis Study. J. Neurochem. 1999, 72, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulke, A.; Nöldner, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M.; Wurglics, M. St. John’s Wort Flavonoids and Their Metabolites Show Antidepressant Activity and Accumulate in Brain after Multiple Oral Doses. Pharmazie 2008, 63, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, J.; Guo, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, H. Antidepressant-Like Activity of Adhyperforin, a Novel Constituent of Hypericum perforatum L. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Dawood, S. Serotonergic Mediation Effects of St John’s Wort in Rats Subjected to Swim Stress. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 21, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Hernandez, R.; Rodríguez-Landa, J.F.; Hernández-Figueroa, J.F.; Saavedra, M.; Ramos-Morales, F.R.; Cruz-Sánchez, J.S. Antidepressant-Like Effects of Two Commercially Available Products of Hypericum perforatum in the Forced Swim Test: A Long-Term Study. J. Med. Plant Res. 2010, 4, 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- Scheggi, S.; Marandino, A.; Del Monte, D.; De Martino, L.; Pelliccia, T.; Fusco, M.d.R.; Petenatti, E.M.; Gambarana, C.; De Feo, V. The Protective Effect of Hypericum Connatum on Stress-Induced Escape Deficit in Rat Is Related to Its Flavonoid Content. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimiuk, E.; Braszko, J.J. Alleviation by Hypericum perforatum of the Stress-Induced Impairment of Spatial Working Memory in Rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2008, 376, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimiuk, E.; Holownia, A.; Braszko, J.J. St. John’s Wort May Relieve Negative Effects of Stress on Spatial Working Memory by Changing Synaptic Plasticity. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2011, 383, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, D.G.; Bettio, L.E.; Cunha, M.P.; Santos, A.R.; Pizzolatti, M.G.; Brighente, I.M.; Rodrigues, A.L. Antidepressant-Like Effect of Rutin Isolated from the Ethanolic Extract from Schinus molle L. In Mice: Evidence for the Involvement of the Serotonergic and Noradrenergic Systems. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 587, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.P.; Reichel, M.; Mühle, C.; Rhein, C.; Gulbins, E.; Kornhuber, J. Brain Membrane Lipids in Major Depression and Anxiety Disorders. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1851, 1052–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.-X.; Ernst, A.M.; Haberkant, P.; Björkholm, P.; Lindahl, E.; Gönen, B.; Tischer, C.; Elofsson, A.; von Heijne, G.; Thiele, C.; et al. Molecular Recognition of a Single Sphingolipid Species by a Protein’s Transmembrane Domain. Nature 2012, 481, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhu, Z.; Delafield, D.G.; Rigby, M.J.; Lu, G.; Braun, M.; Puglielli, L.; Li, L. Spatially and Temporally Probing Distinctive Glycerophospholipid Alterations in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Brain Via High-Resolution Ion Mobility-Enabled Sn-Position Resolved Lipidomics. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Meer, G.; Voelker, D.R.; Feigenson, G.W. Membrane Lipids: Where They Are and How They Behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachowicz, K. The Role of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Neuronal Signaling in Depression and Cognitive Processes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 737, 109555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vance, J.E. Dysregulation of Cholesterol Balance in the Brain: Contribution to Neurodegenerative Diseases. Dis. Model. Mech. 2012, 5, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinichenko, L.S.; Kornhuber, J.; Sinning, S.; Haase, J.; Müller, C.P. Serotonin Signaling through Lipid Membranes. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1298–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, M.; Gonzalez-Gonzalez, I.M.; Smejkalova, T.; Hajdukovic, D.; Skrenkova, K.; Krusek, J.; Horak, M.; Vyklicky, L. Cholesterol Modulates Presynaptic and Postsynaptic Properties of Excitatory Synaptic Transmission. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posse de Chaves, E.; Sipione, S. Sphingolipids and Gangliosides of the Nervous System in Membrane Function and Dysfunction. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Ehehalt, R. Cholesterol, Lipid Rafts, and Disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Blitterswijk, W.J.; van der Luit, A.H.; Veldman, R.J.; Verheij, M.; Borst, J. Ceramide: Second Messenger or Modulator of Membrane Structure and Dynamics? Biochem. J. 2003, 369 Pt 2, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.G.; Chan, R.B.; Bravo, F.V.; Miranda, A.; Silva, R.R.; Zhou, B.; Marques, F.; Pinto, V.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Di Paolo, G.; et al. The Impact of Chronic Stress on the Rat Brain Lipidome. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.S. Sphingolipids in Neuroinflammation: A Potential Target for Diagnosis and Therapy. BMB Rep. 2019, 53, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, A.M.; Bravo, F.V.; Chan, R.B.; Sousa, N.; Di Paolo, G.; Oliveira, T.G. Differential Lipid Composition and Regulation Along the Hippocampal Longitudinal Axis. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracia-Garcia, P.; Rao, V.; Haughey, N.J.; Bandaru, V.V.; Smith, G.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Lobo, A.; Lyketsos, C.G.; Mielke, M.M. Elevated Plasma Ceramides in Depression. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 23, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udagawa, J.; Hino, K. Plasmalogen in the Brain: Effects on Cognitive Functions and Behaviors Attributable to Its Properties. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 188, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.-Y.; Huang, S.-Y.; Su, K.-P. A Meta-Analytic Review of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Compositions in Patients with Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillwell, W.; Wassall, S.R. Docosahexaenoic Acid: Membrane Properties of a Unique Fatty Acid. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2003, 126, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skowronska-Krawczyk, D.; Budin, I. Aging Membranes: Unexplored Functions for Lipids in the Lifespan of the Central Nervous System. Exp. Gerontol. 2020, 131, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keksel, N.; Bussmann, H.; Unger, M.; Drewe, J.; Boonen, G.; Haberlein, H.; Franken, S. St John’s Wort Extract Influences Membrane Fluidity and Composition of Phosphatidylcholine and Phosphatidylethanolamine in Rat C6 Glioblastoma Cells. Phytomedicine 2019, 54, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, H.; Haberlein, H.; Boonen, G.; Drewe, J.; Butterweck, V.; Franken, S. Effect of St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 on the Lateral Mobility of Beta(1)-Adrenergic Receptors in C6 Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussmann, H.; Bremer, S.; Haberlein, H.; Boonen, G.; Drewe, J.; Butterweck, V.; Franken, S. Impact of St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 on Stress Induced Changes in the Lipidome of Pbmc. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremer, S.; Weitkemper, E.; Haberlein, H.; Franken, S. St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 Alters the Membrane Fluidity of C6 Glioma Cells by Influencing Cellular Cholesterol Metabolism. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussmann, H.; Bremer, S.; Hernier, A.M.; Drewe, J.; Häberlein, H.; Franken, S.; Freytag, V.; Boonen, G.; Butterweck, V. St. John’s Wort Extract Ze 117 and Escitalopram Alter Plasma and Hippocampal Lipidome in a Rat Model of Chronic-Stress-Induced Depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, K.; Liu, P.; Lagerholm, B.C. The Lateral Organization and Mobility of Plasma Membrane Components. Cell 2019, 177, 806–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Pasenkiewicz-Gierula, M.; Widomska, J.; Mainali, L.; Raguz, M. High Cholesterol/Low Cholesterol: Effects in Biological Membranes: A Review. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 75, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, B.; Conde, T.; Domingues, I.; Domingues, M.R. Adaptation of Lipid Profiling in Depression Disease and Treatment: A Critical Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merk, V.M.; Boonen, G.; Butterweck, V. St. John’s Wort for Depression: From Neurotransmitters to Membrane Plasticity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411925

Merk VM, Boonen G, Butterweck V. St. John’s Wort for Depression: From Neurotransmitters to Membrane Plasticity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411925

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerk, Verena M., Georg Boonen, and Veronika Butterweck. 2025. "St. John’s Wort for Depression: From Neurotransmitters to Membrane Plasticity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411925

APA StyleMerk, V. M., Boonen, G., & Butterweck, V. (2025). St. John’s Wort for Depression: From Neurotransmitters to Membrane Plasticity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11925. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411925