Spectrum and Clinical Interpretation of TTN Variants in Ecuadorian Patients with Heart Disease: Insights into VUS and Likely Pathogenic Variants

Abstract

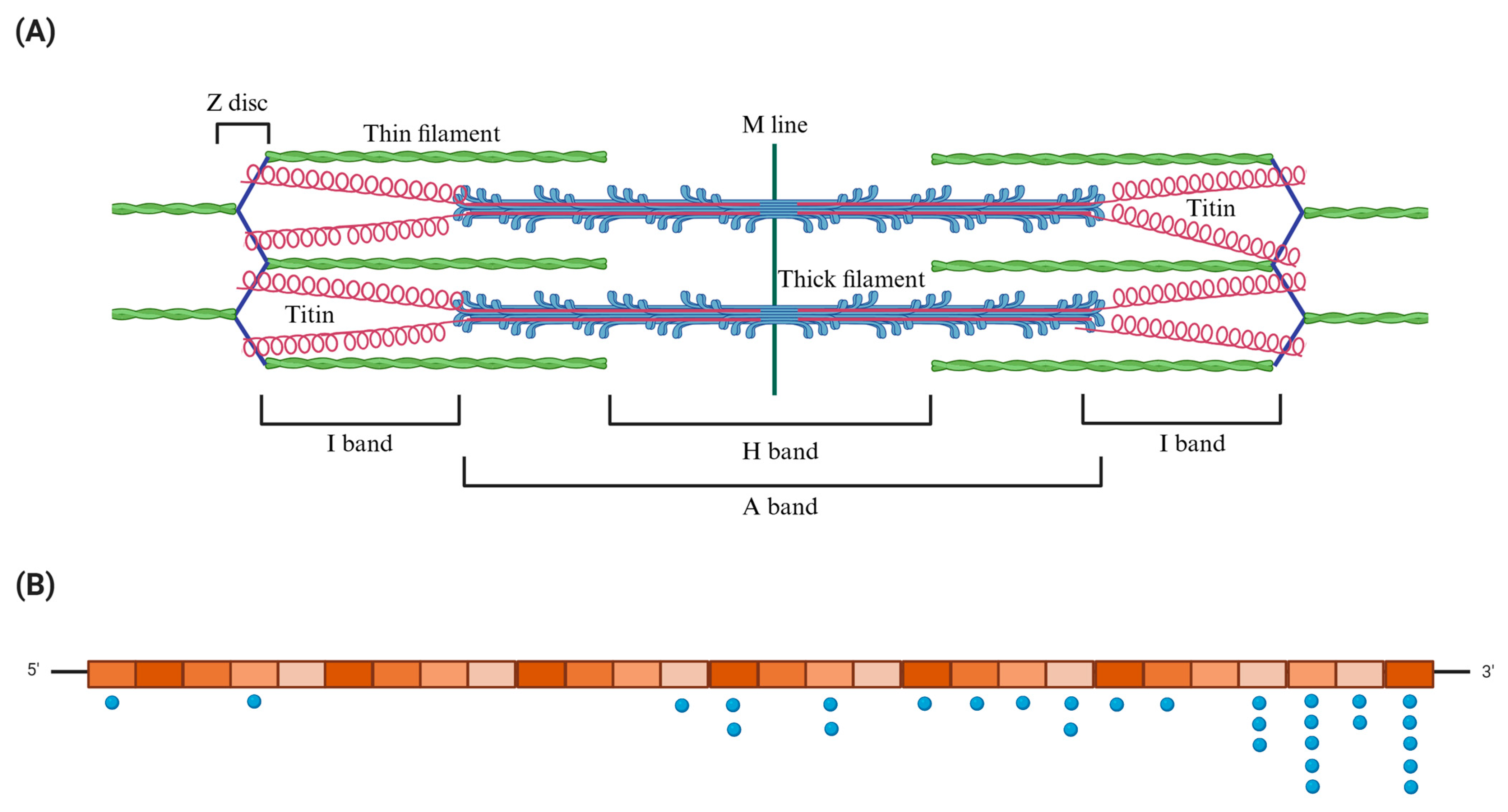

1. Introduction

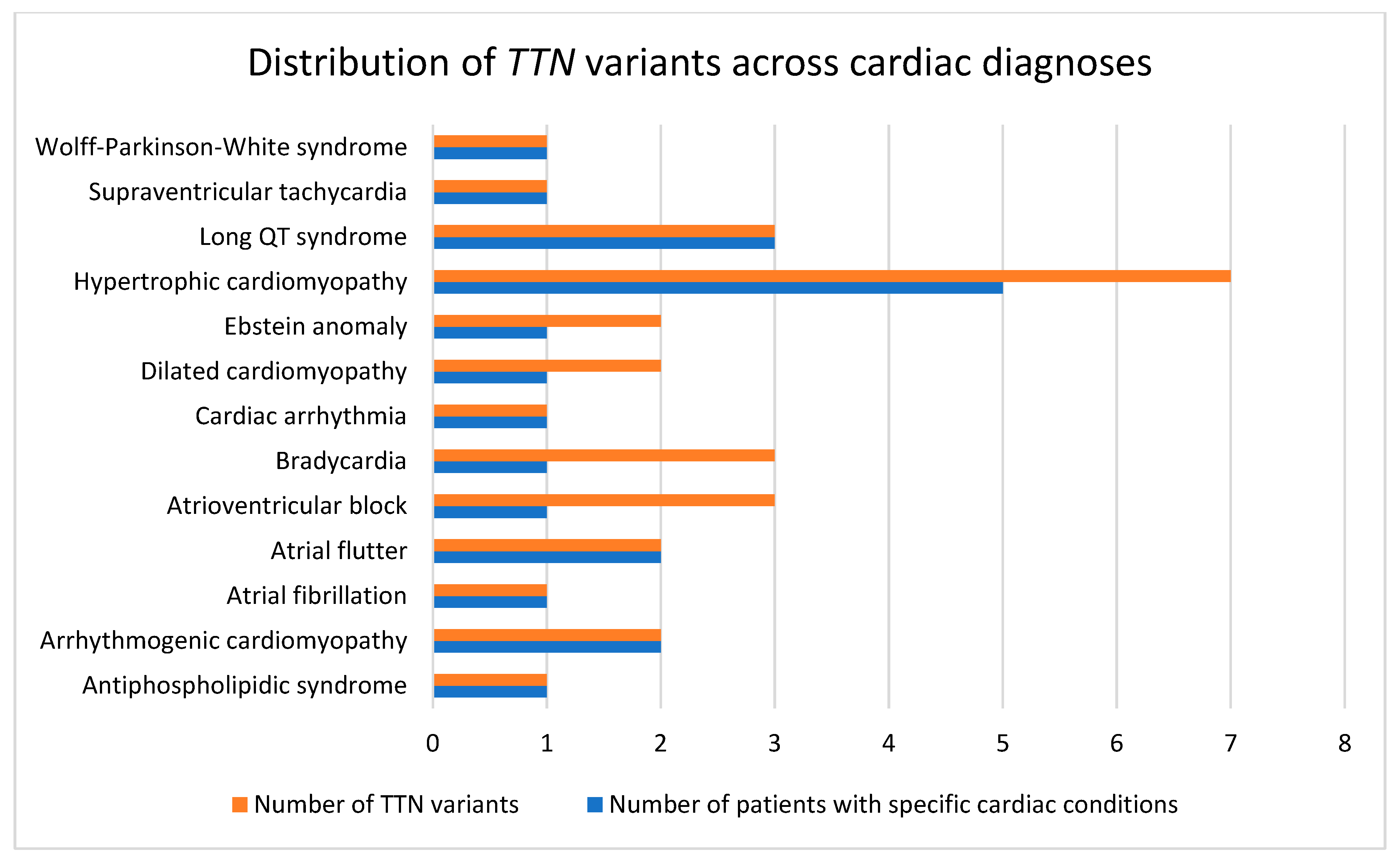

2. Results

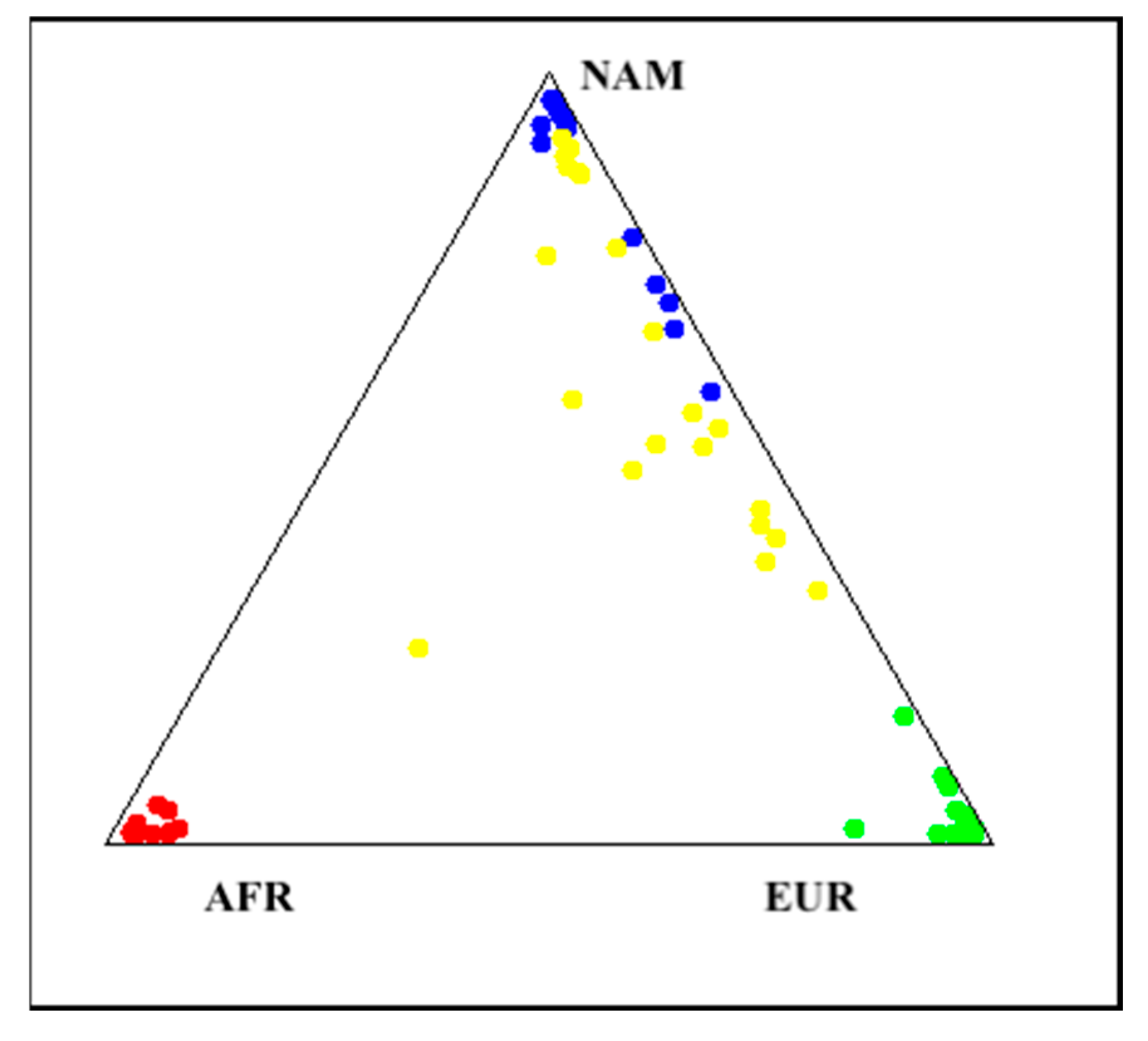

Genetic Ancestry Determination

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Cohort

4.2. Collection of Peripheral Blood and DNA Extraction

4.3. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)

4.4. NGS Data Analysis

4.5. NGS Filtration

4.6. Variant Classification

4.7. Genetic Ancestry Determination

4.8. Ethics Statement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alhuneafat, L.; Al Ta’ani, O.; Arriola-Montenegro, J.; Al-Ajloun, Y.A.; Naser, A.; Chaponan-Lavalle, A.; Ordaya-Gonzales, K.; Pertuz, G.D.R.; Maaita, A.; Jabri, A.; et al. The burden of cardiovascular disease in Latin America and the Caribbean, 1990–2019: An analysis of the global burden of disease study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2025, 428, 133143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Joseph, P.; Lopez-Lopez, J.P.; Lanas, F.; Avezum, A.; Diaz, R.; Camacho, P.A.; Seron, P.; Oliveira, G.; Orlandini, A.; et al. Risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in South America: A PURE substudy. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2841–2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Zha, L. Pathogenesis and Clinical Characteristics of Hereditary Arrhythmia Diseases. Genes 2024, 15, 1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckmann, B.M.; Pfeufer, A.; Kääb, S. Inherited Cardiac Arrhythmias: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2011, 108, 623–633; quiz 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolfayi, A.G.; Kohansal, E.; Ghasemi, S.; Naderi, N.; Hesami, M.; MozafaryBazargany, M.; Moghadam, M.H.; Fazelifar, A.F.; Maleki, M.; Kalayinia, S. Exploring TTN variants as genetic insights into cardiomyopathy pathogenesis and potential emerging clues to molecular mechanisms in cardiomyopathies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Cha, S.; Baek, J.S.; Yu, J.J.; Seo, G.H.; Kang, M.; Do, H.S.; Lee, S.E.; Lee, B.H. Genetic heterogeneity of cardiomyopathy and its correlation with patient care. BMC Med. Genom. 2023, 16, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Guevara-Ramirez, P.; Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Ibarra-Castillo, R.; Laso-Bayas, J.L.; Zambrano, A.K. Exploring Atrial Fibrillation: Understanding the Complex Relation Between Lifestyle and Genetic Factors. J. Med. Cases 2024, 15, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Cruz, E.; Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Guevara-Ramirez, P.; Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Ibarra-Castillo, R.; Laso-Bayas, J.L.; Onofre-Ruiz, P.; Domenech, N.; Ibarra-Rodriguez, A.A.; et al. Associations of MYPN, TTN, SCN5A, MYO6 and ELN Mutations with Arrhythmias and Subsequent Sudden Cardiac Death: A Case Report of an Ecuadorian Individual. Cardiol. Res. 2023, 14, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, O.; Sanchez-Molero, O.; Mademont-Soler, I.; Riuró, H.; Allegue, C.; Coll, M.; Pérez-Serra, A.; Mates, J.; Picó, F.; Iglesias, A.; et al. Rare Titin (TTN) Variants in Diseases Associated with Sudden Cardiac Death. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 25773–25787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, S.R.; Senra, P.d.M.; Linnenkamp, B.D.W.; Vilalva, K.H.; Mizuta, M.H.; dos Santos, B.M.; Stephan, B.d.O.; da Silva, E.A.; Buriti, N.A.; do Val, V.P.; et al. The Role of TTN Gene Variants in Dilated Cardiomyopathy. ABC Heart Fail. Cardiomyopathy 2024, 4, 20240056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroik, D.; Gregorich, Z.R.; Raza, F.; Ge, Y.; Guo, W. Titin: Roles in cardiac function and diseases. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1385821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corden, B.; Jarman, J.; Whiffin, N.; Tayal, U.; Buchan, R.; Sehmi, J.; Harper, A.; Midwinter, W.; Lascelles, K.; Markides, V.; et al. Association of Titin-Truncating Genetic Variants With Life-threatening Cardiac Arrhythmias in Patients With Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Implanted Defibrillators. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubitz, S.A.; Ellinor, P.T. Next-Generation Sequencing for the Diagnosis of Cardiac Arrhythmia Syndromes. Heart Rhythm Off. J. Heart Rhythm Soc. 2015, 12, 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, E.T.; Wang, L.; Conley, A.B.; Rishishwar, L.; Mariño-Ramírez, L.; Valderrama-Aguirre, A.; Jordan, I.K. Genetic ancestry, admixture and health determinants in Latin America. BMC Genom. 2018, 19, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Guevara-Ramirez, P.; Meza-Chico, L.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Laso-Bayas, J.L.; Ibarra-Castillo, R.; Zambrano, A.K. The genomic bases of atrial fibrillation in an Ecuadorian patient: A case report. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1552417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatta, M.; Regalado, E.; Parfenov, M.; Swartzlander, D.; Nagl, A.; Mannello, M.; Lewis, R.; Clemens, D.; Garcia, J.; Ellsworth, R.E.; et al. Analysis of TTN Truncating Variants in >74,000 Cases Reveals New Clinically Relevant Gene Regions. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 2025, 18, e004982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramlich, M.; Michely, B.; Krohne, C.; Heuser, A.; Erdmann, B.; Klaassen, S.; Hudson, B.; Magarin, M.; Kirchner, F.; Todiras, M.; et al. Stress-induced dilated cardiomyopathy in a knock-in mouse model mimicking human titin-based disease. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009, 47, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabish, A.M.; Azzimato, V.; Alexiadis, A.; Buyandelger, B.; Knöll, R. Genetic epidemiology of titin-truncating variants in the etiology of dilated cardiomyopathy. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, Y.; Gramlich, M.; Yoskovitz, G.; Feinberg, M.S.; Afek, A.; Polak-Charcon, S.; Pras, E.; Sela, B.A.; Konen, E.; Weissbrod, O.; et al. Titin Mutation in Familial Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 171, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizawa, M.; Nakagama, Y.; Shindo, T.; Ogawa, S.; Inuzuka, R. Identification of a Novel Titin Variant Underlying Myocardial Involvement in Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Can. J. Cardiol. 2018, 34, 1369.e5–1369.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begay, R.L.; Graw, S.; Sinagra, G.; Merlo, M.; Slavov, D.; Gowan, K.; Jones, K.L.; Barbati, G.; Spezzacatene, A.; Brun, F.; et al. Role of titin missense variants in dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Temaj, G.; Telkoparan-Akillilar, P.; Chichiarelli, S.; Saso, L. An overview of insights and updates on TTN mutations in cardiomyopathies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1668544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Feo, M.F.; Rees, M.; Lillback, V.; Kho, A.L.; Meybatova, A.; Holt, M.; Jungbluth, H.; Muntoni, F.; Baranello, G.; Sarkozy, A.; et al. A comprehensive framework for the interpretation of TTN missense variants. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.M.; Lorenzini, M.; Cicerchia, M.; Ochoa, J.P.; Hey, T.M.; Molina, M.S.; Restrepo-Cordoba, M.A.; Ferro, M.D.; Stolfo, D.; Johnson, R.; et al. Clinical Phenotypes and Prognosis of Dilated Cardiomyopathy Caused by Truncating Variants in the TTN Gene. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, E006832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.G.; Ha, C.; Shin, S.; Park, J.H.; Jang, J.H.; Kim, J.W. Enrichment of titin-truncating variants in exon 327 in dilated cardiomyopathy and its relevance to reduced nonsense-mediated mRNA decay efficiency. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1087359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wei, H.; Hu, D.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Jin, L.; Shi, L.; et al. Clinical Significance of Variants in the TTN Gene in a Large Cohort of Patients With Sporadic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 657689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.O.; Hoque, M.M.; Majid, A.; Gbadegoye, J.O.; Raafat, A.; Lebeche, D. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay: Mechanisms and Recent Implications in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2025, 14, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, M.; Salazar, J.W.; Wojciak, J.; Devine, W.P.; Moffatt, E.; Tseng, Z.H. TTN Variants, Dilated Cardiomyopathy, and Arrhythmic Causes by Autopsy Among Countywide Sudden Deaths. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2025, 11, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, S.; De Marvao, A.; Adami, E.; Fiedler, L.R.; Ng, B.; Khin, E.; Rackham, O.J.L.; Van Heesch, S.; Pua, C.J.; Kui, M.; et al. Titin-truncating variants affect heart function in disease cohorts and the general population. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogan, K. TTN mutations in cardiomyopathy. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, G.; Luo, X.; Zhang, C.; Zou, Y.; Wang, H.; Hui, R.; Wang, J.; Song, L. Titin-Truncating Variants Increase the Risk of Cardiovascular Death in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.; Chin, M.T. Pathogenic Mechanisms of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy beyond Sarcomere Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, M.; Takahashi, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Hiroe, M.; Marumo, F.; Kimura, A. Structural Analysis of the Titin Gene in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Identification of a Novel Disease Gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999, 262, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadmore, K.; Azad, A.J.; Gehmlich, K. The Role of Z-disc Proteins in Myopathy and Cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiabor Barrett, K.M.; Cirulli, E.T.; Bolze, A.; Rowan, C.; Elhanan, G.; Grzymski, J.J.; Lee, W.; Washington, N.L. Cardiomyopathy prevalence exceeds 30% in individuals with TTN variants and early atrial fibrillation. Genet. Med. 2023, 25, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado, E.; Swartzlander, D.; Nagl, A.; Mannello, M.; Lewis, R.; Clemens, D.; Garcia, J.; Morales, A.; Ting, Y.-L.; Vatta, M. P222: TTN truncating variants are enriched in cardiomyopathy/arrhythmia and neuromuscular cases and M-band exon 358 contributes to primary cardiomyopathy/arrhythmia. Genet. Med. Open 2024, 2, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Bian, X.; Lv, J. From genes to clinical management: A comprehensive review of long QT syndrome pathogenesis and treatment. Heart Rhythm O2 2024, 5, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Ibarra-Castillo, R.; Laso-Bayas, J.L.; Guevara-Ramirez, P.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Doménech, N.; Ibarra-Rodríguez, A.A.; Zambrano, A.K. Identifying genomic variant associated with long QT syndrome type 2 in an ecuadorian mestizo individual: A case report. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1395012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akchar, M.; Siddique, M.S. Long QT Syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441860/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Pavel, M.A.; Chen, H.; Hill, M.; Sridhar, A.; Barney, M.; DeSantiago, J.; Owais, A.; Sandu, S.; Darbar, F.A.; Ornelas-Loredo, A.; et al. A Titin Missense Variant Causes Atrial Fibrillation. eLife 2025, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Bakshy, K.; Xu, L.; Nandakumar, P.; Lee, D.; Boerwinkle, E.; Grove, M.L.; Arking, D.E.; Chakravarti, A. Rare coding TTN variants are associated with electrocardiographic QT interval in the general population. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Weng, L.C.; Roselli, C.; Lin, H.; Haggerty, C.M.; Shoemaker, M.B.; Barnard, J.; Arking, D.E.; Chasman, D.I.; Albert, C.M.; et al. Association Between Titin Loss-of-Function Variants and Early-Onset Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2018, 320, 2354–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virk, Z.M.; El-Harasis, M.A.; Yoneda, Z.T.; Anderson, K.C.; Sun, L.; Quintana, J.A.; Murphy, B.S.; Laws, J.L.; Davogustto, G.E.; O’Neill, M.J.; et al. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Pathogenic TTN Variants. Clin. Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 2445–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, Z.; Chen, W.; Xu, J.; Mao, L.; Yu, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, F.; Sun, Y.; et al. Novel missense variant in TTN cosegregating with familial atrioventricular block. Eur. J. Med Genet. 2020, 63, 103752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.Q.; Sun, X.J.; Zhong, L. An uncommon atrioventricular block pattern associated with a novel mutation in TTN. QJM An. Int. J. Med. 2024, 117, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethemiotaki, I. Global prevalence of cardiovascular diseases by gender and age during 2010–2019. Arch. Med. Sci. Atheroscler. Dis. 2023, 8, e196–e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, K.; Gao, W. KLK11 promotes the activation of mTOR and protein synthesis to facilitate cardiac hypertrophy. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, N.; Wang, H.; Zwadlo, C.; Wang, Y.; Grund, A.; Gigina, A.; Hofmann, M.; Kilian, K.; Scharf, G.; Korf-Klingebiel, M.; et al. Anti-androgenic therapy with finasteride improves cardiac function, attenuates remodeling and reverts pathologic gene-expression after myocardial infarction in mice. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 122, 114–124, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.08.011. Erratum in J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2018, 125, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwadlo, C.; Schmidtmann, E.; Szaroszyk, M.; Kattih, B.; Froese, N.; Hinz, H.; Schmitto, J.D.; Widder, J.; Batkai, S.; Bähre, H.; et al. Antiandrogenic therapy with finasteride attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 2015, 131, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Kararigas, G. Mechanistic Pathways of Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Disease. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, A.K.; Gaviria, A.; Cobos-Navarrete, S.; Gruezo, C.; Rodríguez-Pollit, C.; Armendáriz-Castillo, I.; García-Cárdenas, J.M.; Guerrero, S.; López-Cortés, A.; Leone, P.E.; et al. The three-hybrid genetic composition of an Ecuadorian population using AIMs-InDels compared with autosomes, mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Francioli, L.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Collins, R.L.; Kanai, M.; Wang, Q.; Alföldi, J.; Watts, N.A.; Vittal, C.; Gauthier, L.D.; et al. A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature 2024, 625, 92–100, https://doi.org/10.1038/S41586-023-06045-0. Erratum in Nature 2024, 626, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kore, P.; Wilson, M.W.; Tiao, G.; Chao, K.; Darnowsky, P.W.; Watts, N.A.; Mauer, J.H.; Baxter, S.M.; Genome Aggregation Database Consortium; Rehm, H.L.; et al. Improved allele frequencies in gnomAD through local ancestry inference. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadaka, S.; Hishinuma, E.; Komaki, S.; Motoike, I.N.; Kawashima, J.; Saigusa, D.; Inoue, J.; Takayama, J.; Okamura, Y.; Aoki, Y.; et al. jMorp updates in 2020: Large enhancement of multi-omics data resources on the general Japanese population. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D536–D544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiang, W.; Shekhtman, E.; Shao, D.; Revoe, D.; Villamarin, R.; Ivanchenko, E.; Kimura, M.; et al. ALFA: Allele Frequency Aggregator; National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2020; pp. 2–5.

- Karczewski, K.J.; Weisburd, B.; Thomas, B.; Solomonson, M.; Ruderfer, D.M.; Kavanagh, D.; Hamamsy, T.; Lek, M.; Samocha, K.E.; Cummings, B.B.; et al. The ExAC browser: Displaying reference data information from over 60,000 exomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 45, D840–D845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Riley, G.R.; Jang, W.; Rubinstein, W.S.; Church, D.M.; Maglott, D.R. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D980–D985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, S.T.; Ward, M.H.; Kholodov, M.; Baker, J.; Phan, L.; Smigielski, E.M.; Sirotkin, K. dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Alcántara, J.A.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; Martagon, A.J. Biobanking for health in Latin America: A call to action. Lancet Reg. Health-Am. 2025, 41, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlan, E.A.; Malley, K.; Quiroga, G.; Mubarak, E.; Lama, P.; Schutz, A.; Cuevas, A.; Hough, C.L.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Armstrong-Hough, M.; et al. Representation of Hispanic Patients in Clinical Trials for Respiratory Failure: A Systematic Review. Crit. Care Explor. 2025, 7, e1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda, V.; Loesch, D.P.; Guo, B.; Laboulaye, R.; Veliz-Otani, D.; French, J.N.; Leal, T.P.; Gogarten, S.M.; Ikpe, S.; Gouveia, M.H.; et al. Genetics of Latin American Diversity Project: Insights into population genetics and association studies in admixed groups in the Americas. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrell, L.N.; Elhawary, J.R.; Fuentes-Afflick, E.; Witonsky, J.; Bhakta, N.; Wu, A.H.B.; Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Rodríguez-Santana, J.R.; Lenoir, M.A.; Gavin, J.R.; et al. Race and Genetic Ancestry in Medicine—A Time for Reckoning with Racism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Ahmed, R.; Lamri, A.; Anand, S.S. Use of race, ethnicity, and ancestry data in health research. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, C.M.; Damrauer, S.M.; Levin, M.G.; Birtwell, D.; Carey, D.J.; Golden, A.M.; Hartzel, D.N.; Hu, Y.; Judy, R.; Kelly, M.A.; et al. Genomics-First Evaluation of Heart Disease Associated With Titin-Truncating Variants. Circulation 2019, 140, 42–54, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039573. Correction in Ciruclation 2019, 140, e727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.; Kinnamon, D.D.; Haas, G.J.; Hofmeyer, M.; Kransdorf, E.; Ewald, G.A.; Morris, A.A.; Owens, A.; Lowes, B.; Stoller, D.; et al. Genetic Architecture of Dilated Cardiomyopathy in Individuals of African and European Ancestry. JAMA 2023, 330, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.M.; Biesecker, L.G.; Rehm, H.L. Overview of specifications to the ACMG/AMP variant interpretation guidelines. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2019, 103, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, R.; Phillips, C.; Pinto, N.; Santos, C.; Dos Santos, S.E.B.; Amorim, A.; Carracedo, Á.; Gusmão, L. Straightforward inference of ancestry and admixture proportions through ancestry-informative insertion deletion multiplexing. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, N.A. Standardized subsets of the HGDP-CEPH Human Genome Diversity Cell Line Panel, accounting for atypical and duplicated samples and pairs of close relatives. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2006, 70, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SAMPLE | Diagnosis | Exon | HGVSC | HGVSP | Consequence | Zygosity | rs | Allele Frequency | ACMG/AMP Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADN001 | Long QT syndrome | 358/363 | c.103957C>T | p.(Arg34653Cys) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs773002407 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| ADN008 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 326/363 | c.74135T>C | p.(Leu24712Pro) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs570875618 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| 284/363 | c.55195C>T | p.(Pro18399Ser) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs774591174 | <0.01% | PM2 | ||

| 244/363 | c.44986C>T | p.(Arg14996Cys) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs765602798 | <0.01% | PM2 | ||

| BP6 | |||||||||

| ADN013 | Long QT syndrome | 358/363 | c.101959C>T | p.(His33987Tyr) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 |

| ADN014 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 358/363 | c.102827G>A | p.(Arg34276Gln) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs199932621 | 0.02% | PM2 |

| BP6 | |||||||||

| ADN023 | Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy | 325/363 | c.69638G>A | p.(Arg23213His) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs374883884 | 0.02% | PM2 |

| ADN037 | Antiphospholipidic syndrome | 326/363 | c.85286T>A | p.(Val28429Glu) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs747216991 | 0.01% | PM2 |

| ADN050 | Dilated cardiomyopathy | 267/363 | c.50293A>T | p.(Lys16765Ter) | stop_gained | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PVS1 |

| PM2 | |||||||||

| 326/363 | c.78328A>G | p.(Thr26110Ala) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 | ||

| ADN058 | Atrial Flutter | 326/363 | c.73847G>A | p.(Arg24616Gln) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs201694149 | 0.04% | PM2 |

| BP6 | |||||||||

| ADN093 | Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy | 344/363 | c.95540G>A | p.(Arg31847His) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs771179752 | 0.07% | PM2 |

| PP3 | |||||||||

| ADN097 | Atrial flutter | 170/363 | c.36418C>T | p.(Pro12140Ser) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs1225570991 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| BP4 | |||||||||

| ADN099 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 344/363 | c.95464G>A | p.(Glu31822Lys) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs986919717 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| ADN100 | Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome | 169/363 | c.36281T>C | p.(Val12094Ala) | missense_variant, splice_region_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 |

| BP4 | |||||||||

| ADN101 | Atrial fibrillation | 204/363 | c.39250G>A | p.(Val13084Met) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs72650062 | 0% | PM2 |

| BP4 | |||||||||

| ADN103 | Supraventricular tachycardia | 358/363 | c.102839C>T | p.(Thr34280Ile) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs886042505 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| ADN106 | Cardiac arrhythmia | 272/363 | c.51546C>A | p.(Tyr17182Ter) | stop_gained | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PVS1 |

| PM2 | |||||||||

| ADN116 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 3/363 | c.271A>G | p.(Ser91Gly) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 |

| ADN117 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 253/363 | c.47498T>A | p.(Val15833Glu) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs758495958 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| PP3 | |||||||||

| ADN120 | Long QT syndrome | 170/363 | c.36418C>T | p.(Pro12140Ser) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs1225570991 | <0.01% | PM2 |

| BP4 | |||||||||

| ADN130 | Atrioventricular block | 313/363 | c.65672C>T | p.(Pro21891Leu) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs397517662 | 0.02% | PM2 |

| PP3 | |||||||||

| 231/363 | c.42625T>A | p.(Ser14209Thr) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 | ||

| 204/363 | c.39250G>A | p.(Val13084Met) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs72650062 | 0% | PM2 | ||

| BP4 | |||||||||

| ADN146 | Bradycardia | 358/363 | c.101824C>T | p.(Pro33942Ser) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 |

| 326/363 | c.74935T>C | p.(Tyr24979His) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs1364199300 | <0.01% | PM2 | ||

| PP3 | |||||||||

| 315/363 | c.66313G>T | p.(Val22105Phe) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 | ||

| ADN150 | Ebstein anomaly | 287/363 | c.55730T>C | p.(Ile18577Thr) | missense_variant, splice_region_variant | Heterozygous | no rs | N/A | PM2 |

| 49/363 | c.14302G>A | p.(Gly4768Ser) | missense_variant | Heterozygous | rs727503652 | <0.01% | PM2 | ||

| PP3 | |||||||||

| BP6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guevara-Ramírez, P.; Cadena-Ullauri, S.; Tamayo-Trujillo, R.; Ruiz-Pozo, V.A.; Paz-Cruz, E.; Ibarra-Castillo, R.; Laso-Bayas, J.L.; Zambrano, A.K. Spectrum and Clinical Interpretation of TTN Variants in Ecuadorian Patients with Heart Disease: Insights into VUS and Likely Pathogenic Variants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411896

Guevara-Ramírez P, Cadena-Ullauri S, Tamayo-Trujillo R, Ruiz-Pozo VA, Paz-Cruz E, Ibarra-Castillo R, Laso-Bayas JL, Zambrano AK. Spectrum and Clinical Interpretation of TTN Variants in Ecuadorian Patients with Heart Disease: Insights into VUS and Likely Pathogenic Variants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411896

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuevara-Ramírez, Patricia, Santiago Cadena-Ullauri, Rafael Tamayo-Trujillo, Viviana A. Ruiz-Pozo, Elius Paz-Cruz, Rita Ibarra-Castillo, José Luis Laso-Bayas, and Ana Karina Zambrano. 2025. "Spectrum and Clinical Interpretation of TTN Variants in Ecuadorian Patients with Heart Disease: Insights into VUS and Likely Pathogenic Variants" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411896

APA StyleGuevara-Ramírez, P., Cadena-Ullauri, S., Tamayo-Trujillo, R., Ruiz-Pozo, V. A., Paz-Cruz, E., Ibarra-Castillo, R., Laso-Bayas, J. L., & Zambrano, A. K. (2025). Spectrum and Clinical Interpretation of TTN Variants in Ecuadorian Patients with Heart Disease: Insights into VUS and Likely Pathogenic Variants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411896