Genome-Wide, High-Density Genotyping Approaches for Plant Germplasm Characterisation (Methods and Applications)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Plant Germplasm Genotyping Approaches

2.1. Reduced Representation Sequencing (RRS) Methods

2.2. Whole Genome Resequencing (WGRS)

2.3. SNP Genotyping Arrays

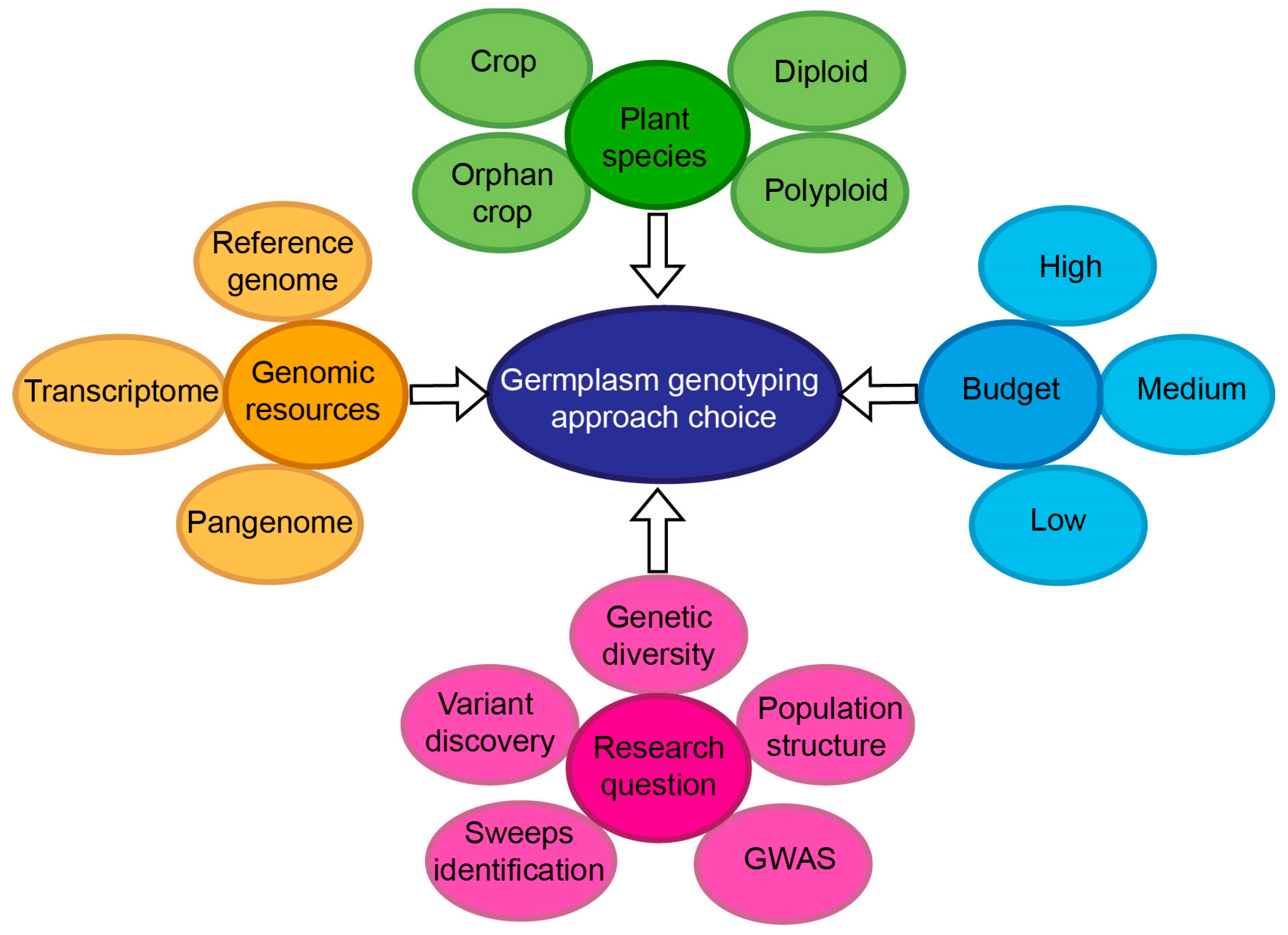

2.4. Choosing the Right Genome-Wide Genotyping Platform and Other Considerations

3. Applications of Genome-Wide Genotyping Data in Germplasm Characterisation

4. Examples of High-Resolution Genotyping Data Applications in Selected Plant Groups

4.1. Cereals

4.2. Pseudocereals

4.3. Tuberous Plants

4.4. Legumes

4.5. Oil Plants

4.6. Vegetables

4.7. Ornamentals

4.8. Fruit and Nut Trees

4.9. Others

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments. The Third Report on The State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; FAO Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 978-92-5-139675-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hedden, P. The Genes of the Green Revolution. Trends Genet. 2003, 19, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, P.L. Green Revolution: Impacts, Limits, and the Path Ahead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12302–12308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, A.; Zamir, D. Unused Natural Variation Can Lift Yield Barriers in Plant Breeding. PLoS Biol. 2004, 2, e245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamuyao, R.; Chin, J.H.; Pariasca-Tanaka, J.; Pesaresi, P.; Catausan, S.; Dalid, C.; Slamet-Loedin, I.; Tecson-Mendoza, E.M.; Wissuwa, M.; Heuer, S. The Protein Kinase Pstol1 from Traditional Rice Confers Tolerance of Phosphorus Deficiency. Nature 2012, 488, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascher, M.; Schreiber, M.; Scholz, U.; Graner, A.; Reif, J.C.; Stein, N. Genebank Genomics Bridges the Gap between the Conservation of Crop Diversity and Plant Breeding. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 1076–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal-Yepes, M.; Ospina, J.A.; Aranzales, E.; Velez-Tobon, M.; Correa Abondano, M.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.C.; Wenzl, P. Identifying Genetically Redundant Accessions in the World’s Largest Cassava Collection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1338377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langridge, P.; Waugh, R. Harnessing the Potential of Germplasm Collections. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 200–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gireesh, C.; Sundaram, R.M.; Anantha, S.M.; Pandey, M.K.; Madhav, M.S.; Rathod, S.; Yathish, K.R.; Senguttuvel, P.; Kalyani, B.M.; Ranjith, E.; et al. Nested Association Mapping (NAM) Populations: Present Status and Future Prospects in the Genomics Era. CRC Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2021, 40, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzebelus, D. Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) Markers for Genetic Diversity. In Genetic Diversity and Erosion in Plants; Sustainable Development and Biodiversity; Ahuja, M.R., Jain, S.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 295–309. ISBN 978-3-319-25637-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai, G.; Shi, A.; Kandel, D.R.; Solís-Gracia, N.; da Silva, J.A.; Avila, C.A. Genome-Wide Simple Sequence Repeats (SSR) Markers Discovered from Whole-Genome Sequence Comparisons of Multiple Spinach Accessions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, M.K.; Bagchi, M.; Nath, U.K.; Biswas, D.; Natarajan, S.; Jesse, D.M.I.; Park, J.I.; Nou, I.S. Transcriptome Wide SSR Discovery Cross-Taxa Transferability and Development of Marker Database for Studying Genetic Diversity Population Structure of Lilium Species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Huang, S.; Pan, G.; Chang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Tang, H.; Chen, A.; Peng, D.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Cannabis Based on the Genome-Wide Development of Simple Sequence Repeat Markers. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy-Trojanowska, M.; Bolibok, H. Characteristics and a Comparison of Three Classes of Microsatellite-Based Markers and Their Application in Plants. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2004, 9, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Shavvon, R.S.; Qi, H.L.; Mafakheri, M.; Fan, P.Z.; Wu, H.Y.; Vahdati, F.B.; Al-Shmgani, H.S.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, J. Unravelling the Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Common Walnut in the Iranian Plateau. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyngkhoi, F.; Saini, N.; Gaikwad, A.B.; Thirunavukkarasu, N.; Verma, P.; Silvar, C.; Yadav, S.; Khar, A. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Onion (Allium cepa L.) Accessions Based on Morphological and Molecular Approaches. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2517–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-J.; Sebastin, R.; Cho, G.-T.; Yoon, M.; Lee, G.-A.; Hyun, D.-Y. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Potato Germplasm in RDA-Genebank: Utilization for Breeding and Conservation. Plants 2021, 10, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, H.; Mir, A.H.; Tyagi, S.; Wani, A.A.; Jan, N.; Yasin, M.; Mir, J.I.; Mondal, B.; Khan, M.A.; Mir, R.R. Assessment of Molecular Genetic Diversity of 384 Chickpea Genotypes and Development of Core Set of 192 Genotypes for Chickpea Improvement Programs. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2022, 69, 1193–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.; van Dooijeweert, W.; Durel, C.E.; Denancé, C.; Rutten, M.; Howard, N.P. SNP Genotyping Dutch Heritage Apple Cultivars Allows for Germplasm Characterization, Curation, and Pedigree Reconstruction Using Genotypic Data from Multiple Collection Sites across the World. Tree Genet. Genomes 2024, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshire, R.J.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Sun, Q.; Poland, J.A.; Kawamoto, K.; Buckler, E.S.; Mitchell, S.E. A Robust, Simple Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) Approach for High Diversity Species. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansaloni, C.; Petroli, C.; Jaccoud, D.; Carling, J.; Detering, F.; Grattapaglia, D.; Kilian, A. Diversity Arrays Technology (DArT) and next-Generation Sequencing Combined: Genome-Wide, High Throughput, Highly Informative Genotyping for Molecular Breeding of Eucalyptus. BMC Proc. 2011, 5, P54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.W.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Etter, P.D.; Boone, J.Q.; Catchen, J.M.; Blaxter, M.L. Genome-Wide Genetic Marker Discovery and Genotyping Using next-Generation Sequencing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, B.K.; Weber, J.N.; Kay, E.H.; Fisher, H.S.; Hoekstra, H.E. Double Digest RADseq: An Inexpensive Method for de Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping in Model and Non-Model Species. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheben, A.; Batley, J.; Edwards, D. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Approaches to Characterize Crop Genomes: Choosing the Right Tool for the Right Application. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiranage, D.S.R.; Rey, E.; Emrani, N.; Wellman, G.; Schmid, K.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Tester, M.; Jung, C. Genome-Wide Association Study in Quinoa Reveals Selection Pattern Typical for Crops with a Short Breeding History. Elife 2022, 11, e66873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan-Rodriguez, D.; Koboyi, B.W.; Werghi, S.; Till, B.J.; Maksymiuk, J.; Shoormij, F.; Hilderlith, A.; Hawliczek, A.; Królik, M.; Bolibok-Brągoszewska, H. Phosphate Transporter Gene Families in Rye (Secale cereale L.)—Genome-Wide Identification, Characterization and Sequence Diversity Assessment via DArTreseq. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1529358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Ge, S.; Jensen, J.D.; Hu, F.; Li, X.; Dong, Y.; Gutenkunst, R.N.; Fang, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Resequencing 50 Accessions of Cultivated and Wild Rice Yields Markers for Identifying Agronomically Important Genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gou, Z.; Lyu, J.; Li, W.; Yu, Y.; Shu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; et al. Resequencing 302 Wild and Cultivated Accessions Identifies Genes Related to Domestication and Improvement in Soybean. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, R.K.; Roorkiwal, M.; Sun, S.; Bajaj, P.; Chitikineni, A.; Thudi, M.; Singh, N.P.; Du, X.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Khan, A.W.; et al. A Chickpea Genetic Variation Map Based on the Sequencing of 3,366 Genomes. Nature 2021, 599, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganal, M.W.; Polley, A.; Graner, E.M.; Plieske, J.; Wieseke, R.; Luerssen, H.; Durstewitz, G. Large SNP Arrays for Genotyping in Crop Plants. J. Biosci. 2012, 37, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josia, C.; Mashingaidze, K.; Amelework, A.B.; Kondwakwenda, A.; Musvosvi, C.; Sibiya, J. SNP-Based Assessment of Genetic Purity and Diversity in Maize Hybrid Breeding. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kang, M.Y.; Shim, E.J.; Oh, J.H.; Seo, K.I.; Kim, K.S.; Sim, S.C.; Chung, S.M.; Park, Y.; Lee, G.P.; et al. Genome-Wide Core Sets of SNP Markers and Fluidigm Assays for Rapid and Effective Genotypic Identification of Korean Cultivars of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawliczek, A.; Bolibok, L.; Tofil, K.; Borzęcka, E.; Jankowicz-Cieślak, J.; Gawroński, P.; Kral, A.; Till, B.J.; Bolibok-Brągoszewska, H. Deep Sampling and Pooled Amplicon Sequencing Reveals Hidden Genic Variation in Heterogeneous Rye Accessions. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Hong, W.; Jiang, C.; Guan, N.; Ma, C.; Zeng, H.; et al. SLAF-Seq: An Efficient Method of Large-Scale De Novo SNP Discovery and Genotyping Using High-Throughput Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamaneh, D.; Laroche, J.; Bastien, M.; Abed, A.; Belzile, F. Fast-GBS: A New Pipeline for the Efficient and Highly Accurate Calling of SNPs from Genotyping-by-Sequencing Data. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaubitz, J.C.; Casstevens, T.M.; Lu, F.; Harriman, J.; Elshire, R.J.; Sun, Q.; Buckler, E.S. TASSEL-GBS: A High Capacity Genotyping by Sequencing Analysis Pipeline. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Lipka, A.E.; Glaubitz, J.; Elshire, R.; Cherney, J.H.; Casler, M.D.; Buckler, E.S.; Costich, D.E. Switchgrass Genomic Diversity, Ploidy, and Evolution: Novel Insights from a Network-Based SNP Discovery Protocol. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchen, J.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Bassham, S.; Amores, A.; Cresko, W.A. Stacks: An Analysis Tool Set for Population Genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 3124–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, E.; Marth, G. Haplotype-Based Variant Detection from Short-Read Sequencing. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1207.3907. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce Framework for Analyzing next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browning, B.L.; Zhou, Y.; Browning, S.R. A One-Penny Imputed Genome from Next-Generation Reference Panels. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 103, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yang, S.; Araya, S.; Quigley, C.; Taliercio, E.; Mian, R.; Specht, J.E.; Diers, B.W.; Song, Q. Genotype Imputation for Soybean Nested Association Mapping Population to Improve Precision of QTL Detection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 1797–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinacci, S.; Delaneau, O.; Marchini, J. Genotype Imputation Using the Positional Burrows Wheeler Transform. PLoS Genet. 2020, 16, e1009049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, B.; Fuchsberger, C.; Stephens, M.; Marchini, J.; Abecasis, G.R. Fast and Accurate Genotype Imputation in Genome-Wide Association Studies through Pre-Phasing. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paril, J.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Malmberg, M.M. Imputef: Imputation of Polyploid Genotype Classes and Allele Frequencies. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.V.; Lipka, A.E.; Sacks, E.J. PolyRAD: Genotype Calling with Uncertainty from Sequencing Data in Polyploids and Diploids. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2019, 9, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarts, K.; Li, H.; Romero Navarro, J.A.; An, D.; Romay, M.C.; Hearne, S.; Acharya, C.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Mitchell, S.; Elshire, R.J.; et al. Novel Methods to Optimize Genotypic Imputation for Low-Coverage, Next-Generation Sequence Data in Crop Plants. Plant Genome 2014, 7, plantgenome2014.05.0023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.R. Variant Calling in Polyploids for Population and Quantitative Genetics. Appl. Plant Sci. 2024, 12, e11607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; Depristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The Variant Call Format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Hao, Y.; Xia, X.; Khan, A.; Xu, Y.; Varshney, R.K.; He, Z. Crop Breeding Chips and Genotyping Platforms: Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fechete, L.I.; Himmelbach, A.; Poehlein, A.; Lohwasser, U.; Börner, A.; Maalouf, F.; Kumar, S.; Khazaei, H.; Stein, N.; et al. Optimization of Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) for Germplasm Fingerprinting and Trait Mapping in Faba Bean. Legume Sci. 2024, 6, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickland, D.P.; Battu, G.; Hudson, K.A.; Diers, B.W.; Hudson, M.E. A Comparison of Genotyping-by-Sequencing Analysis Methods on Low-Coverage Crop Datasets Shows Advantages of a New Workflow, GB-EaSy. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamalutdinov, A.; Boldyrev, S.; Ben, C.; Gentzbittel, L. The Evaluation of Different Combinations of Enzyme Set, Aligner and Caller in GBS Sequencing of Soybean. Plant Methods 2025, 21, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, R.N.; Jacobs, A.; Wilder, A.P.; Therkildsen, N.O. A Beginner’s Guide to Low-Coverage Whole Genome Sequencing for Population Genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 5966–5993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemay, M.A.; Sibbesen, J.A.; Torkamaneh, D.; Hamel, J.; Levesque, R.C.; Belzile, F. Combined Use of Oxford Nanopore and Illumina Sequencing Yields Insights into Soybean Structural Variation Biology. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, A.; Gowda, M.; Nair, S.K.; Hao, Z.; Lu, Y.; et al. Applications of Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS) in Maize Genetics and Breeding. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, J.; Bombarely, A.; Fornell, C.D.; Luque, F.; Fernández-Ocaña, A.M. Comparative Analysis of Genotyping by Sequencing and Whole-Genome Sequencing Methods in Diversity Studies of Olea europaea L. Plants 2021, 10, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.C.T.; Konzen, E.R.; Caldeira, M.V.W.; de Oliveira Godinho, T.; Maluf, L.P.; Moreira, S.O.; da Silva Carvalho, C.; Leal, B.S.S.; dos Santos Azevedo, C.; Momolli, D.R.; et al. Genetic Resources of African Mahogany in Brazil: Genomic Diversity and Structure of Forest Plantations. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, R.; Prabhakaran, S.; Tiwari, A.; Joshi, D.; Chandora, R.; Taj, G.; Jahan, T.; Singh, S.P.; Jaiswal, J.P.; Joshi, R.; et al. Genetic Distances and Genome Wide Population Structure Analysis of a Grain Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) Diversity Panel Using Genotyping by Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Fan, G.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liao, K. Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, and Relationships of Apricot (Prunus) Based on Restriction Site-Associated DNA Sequencing. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdugo-Cely, J.A.; Cortés, A.J.; López-Hernández, F.; Delgadillo-Durán, P.; Cerón-Souza, I.; Reyes-Herrera, P.H.; Navas-Arboleda, A.A.; Yockteng, R. Pleistocene-Dated Genomic Divergence of Avocado Trees Supports Cryptic Diversity in the Colombian Germplasm. Tree Genet. Genomes 2023, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akech, V.; Bengtsson, T.; Ortiz, R.; Swennen, R.; Uwimana, B.; Ferreira, C.F.; Amah, D.; Amorim, E.P.; Blisset, E.; Van den Houwe, I.; et al. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure in Banana (Musa Spp.) Breeding Germplasm. Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, S.G.; Jost, M.; Taketa, S.; Mazón, E.R.; Himmelbach, A.; Oppermann, M.; Weise, S.; Knüpffer, H.; Basterrechea, M.; König, P.; et al. Genebank Genomics Highlights the Diversity of a Global Barley Collection. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanero, B.R.; Kulkarni, K.P.; Vorsa, N.; Reddy, U.K.; Natarajan, P.; Elavarthi, S.; Iorizzo, M.; Melmaiee, K. Genomic and Evolutionary Relationships among Wild and Cultivated Blueberry Species. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.P.; Stamm, M.; Talukder, Z.I.; Fiedler, J.; Horvath, A.P.; Horvath, G.A.; Chao, W.S.; Anderson, J.V. A New Diversity Panel for Winter Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) Genome-Wide Association Studies. Agronomy 2020, 10, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Muñoz, M.A.; López-Hernández, F.; Cortés, A.J.; Roda, F.; Castaño, E.; Montoya, G.; Henao-Rojas, J.C. Pangenomic and Phenotypic Characterization of Colombian Capsicum Germplasm Reveals the Genetic Basis of Fruit Quality Traits. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Hernández, F.; Cortés, A.J. Last-Generation Genome–Environment Associations Reveal the Genetic Basis of Heat Tolerance in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muli, J.K.; Neondo, J.O.; Kamau, P.K.; Michuki, G.N.; Odari, E.; Budambula, N.L.M. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Wild and Cultivated Crotalaria Species Based on Genotyping-by-Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadizadeh, H.; Bahri, B.A.; Qi, P.; Wilde, H.D.; Devos, K.M. Intra- and Interspecific Diversity Analyses in the Genus Eremurus in Iran Using Genotyping-by- Sequencing Reveal Geographic Population Structure. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigita, G.; Dung, T.P.; Pervin, M.N.; Duong, T.T.; Imoh, O.N.; Monden, Y.; Nishida, H.; Tanaka, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Kawazu, Y.; et al. Elucidation of Genetic Variation and Population Structure of Melon Genetic Resources in the NARO Genebank, and Construction of the World Melon Core Collection. Breed. Sci. 2023, 73, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, W.A.; Avni, R.; Birkett, C.L.; Itaya, A.; Wight, C.P.; Bellavance, J.; Brodführer, S.; Canales, F.J.; Carlson, C.H.; Fiebig, A.; et al. Global Genomic Population Structure of Wild and Cultivated Oat Reveals Signatures of Chromosome Rearrangements. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolkafli, S.H.; Marjuni, M.; Abdullah, N.; Singh, R.; Ithnin, M. Exploring Diversity in African Oil Palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) Germplasm Populations via Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 6111–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rispail, N.; Wohor, O.Z.; Osuna-Caballero, S.; Barilli, E.; Rubiales, D. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of a Wide Pisum Spp. Core Collection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Chen, S.Y.; Chiu, S.Y.; Lai, C.Y.; Lai, P.H.; Shehzad, T.; Wu, W.L.; Chen, W.H.; Paterson, A.H.; Chen, H.H. High-Density Genetic Map and Genome-Wide Association Studies of Aesthetic Traits in Phalaenopsis Orchids. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, H.K.; Del Rio, A.H.; Bamberg, J.B.; Shannon, L.M. Potato Soup: Analysis of Cultivated Potato Gene Bank Populations Reveals High Diversity and Little Structure. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1429279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawliczek, A.; Borzęcka, E.; Tofil, K.; Alachiotis, N.; Bolibok, L.; Gawroński, P.; Siekmann, D.; Hackauf, B.; Dušinský, R.; Švec, M.; et al. Selective Sweeps Identification in Distinct Groups of Cultivated Rye (Secale cereale L.) Germplasm Provides Potential Candidate Genes for Crop Improvement. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seay, D.; Szczepanek, A.; De La Fuente, G.N.; Votava, E.; Abdel-Haleem, H. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of a Large USDA Sesame Collection. Plants 2024, 13, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippi, C.V.; Merino, G.A.; Montecchia, J.F.; Aguirre, N.C.; Rivarola, M.; Naamati, G.; Fass, M.I.; Álvarez, D.; Di Rienzo, J.; Heinz, R.A.; et al. Genetic Diversity, Population Structure and Linkage Disequilibrium Assessment among International Sunflower Breeding Collections. Genes 2020, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, N.; Toyoshima, M.; Fujita, M.; Fukuda, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ueno, M.; Tanaka, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishihara, E.; Mizukoshi, H.; et al. The Genotype-Dependent Phenotypic Landscape of Quinoa in Salt Tolerance and Key Growth Traits. DNA Res. 2020, 27, dsaa022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansaloni, C.; Franco, J.; Santos, B.; Percival-Alwyn, L.; Singh, S.; Petroli, C.; Campos, J.; Dreher, K.; Payne, T.; Marshall, D.; et al. Diversity Analysis of 80,000 Wheat Accessions Reveals Consequences and Opportunities of Selection Footprints. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agre, P.; Asibe, F.; Darkwa, K.; Edemodu, A.; Bauchet, G.; Asiedu, R.; Adebola, P.; Asfaw, A. Phenotypic and Molecular Assessment of Genetic Structure and Diversity in a Panel of Winged Yam (Dioscorea alata) Clones and Cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, S.; Delvento, C.; Ricciardi, L.; Lotti, C.; Ciani, E.; D’Agostino, N. Recommendations for Choosing the Genotyping Method and Best Practices for Quality Control in Crop Genome-Wide Association Studies. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, Z.; Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Deng, W.; Wu, J. Leveraging Whole-Genome Resequencing to Uncover Genetic Diversity and Promote Conservation Strategies for Ruminants in Asia. Animals 2025, 15, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. 2010. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and Accurate Short Read Alignment with Burrows—Wheeler Transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast Gapped-Read Alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Heffelfinger, C.; Zhao, H.; Dellaporta, S.L. Benchmarking Variant Identification Tools for Plant Diversity Discovery. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happ, M.M.; Wang, H.; Graef, G.L.; Hyten, D.L. Generating High Density, Low Cost Genotype Data in Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2019, 9, 2153–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Romeral, J.; Castanera, R.; Casacuberta, J.; Domingo, C. Deciphering the Genetic Basis of Allelopathy in Japonica Rice Cultivated in Temperate Regions Using a Genome-Wide Association Study. Rice 2024, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, P.; Platts, A.; Wang, L.L.; Coon, M.; Nguyen, T.; Wang, L.; Land, S.J.; Lu, X.; Ruden, D.M.; Cingolani, P.; et al. A Program for Annotating and Predicting the Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms, SnpEff. Fly 2012, 6, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, R.; Ruano-Rubio, V.; DePristo, M.A.; Fennell, T.J.; Carneiro, M.O.; Van der Auwera, G.A.; Kling, D.E.; Gauthier, L.D.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Roazen, D.; et al. Scaling Accurate Genetic Variant Discovery to Tens of Thousands of Samples. bioRxiv 2017, 1, 201178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.X.; Zheng, P.; Bhamidimarri, S.; Liu, X.P.; Main, D. The Impact of Genotyping-by-Sequencing Pipelines on SNP Discovery and Identification of Markers Associated with Verticillium Wilt Resistance in Autotetraploid Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pook, T.; Mayer, M.; Geibel, J.; Weigend, S.; Cavero, D.; Schoen, C.C.; Simianer, H. Improving Imputation Quality in Beagle for Crop and Livestock Data. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2020, 10, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howie, B.N.; Donnelly, P.; Marchini, J. A Flexible and Accurate Genotype Imputation Method for the next Generation of Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLoS Genet. 2009, 5, e1000529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, E.M.; Bradbury, P.J.; Cinta Romay, M.; Buckler, E.S.; Robbins, K.R. Genome-Wide Imputation Using the Practical Haplotype Graph in the Heterozygous Crop Cassava. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2022, 12, jkab383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonen, S.; Wimmer, V.; Gaynor, R.C.; Byrne, E.; Gorjanc, G.; Hickey, J.M. A Heuristic Method for Fast and Accurate Phasing and Imputation of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism Data in Bi-Parental Plant Populations. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Money, D.; Gardner, K.; Migicovsky, Z.; Schwaninger, H.; Zhong, G.Y.; Myles, S. LinkImpute: Fast and Accurate Genotype Imputation for Nonmodel Organisms. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2015, 5, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Dias, J.; Singh, A.; Graf, C.; Stetter, M.G. Genetic Incompatibilities and Evolutionary Rescue by Wild Relatives Shaped Grain Amaranth Domestication. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2023, 40, msad177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas-Gutiérrez, G.P.; López-Hernández, F.; Cortés, A.J. Whole Genome Resequencing of 205 Avocado Trees Unveils the Genomic Patterns of Racial Divergence in the Americas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, K.; Bostan, H.; Rolling, W.; Turner-Hissong, S.; Macko-Podgórni, A.; Senalik, D.; Liu, S.; Seth, R.; Curaba, J.; Mengist, M.F.; et al. Population Genomics Identifies Genetic Signatures of Carrot Domestication and Improvement and Uncovers the Origin of High-Carotenoid Orange Carrots. Nat. Plants 2023, 9, 1643–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekbib, Y.; Tesfaye, K.; Dong, X.; Saina, J.K.; Hu, G.W.; Wang, Q.F. Whole-Genome Resequencing of Coffea arabica L. (Rubiaceae) Genotypes Identify SNP and Unravels Distinct Groups Showing a Strong Geographical Pattern. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denning-James, K.E.; Chater, C.; Cortés, A.J.; Blair, M.W.; Peláez, D.; Hall, A.; De Vega, J.J. Genome-Wide Association Mapping Dissects the Selective Breeding of Determinacy and Photoperiod Sensitivity in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2025, 15, jkaf090, Erratum in G3 Genes. Genomes Genet. 2025, 15, jkaf141. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkaf141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Hui, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, T. Whole-Genome Resequencing of 240 Gossypium Barbadense Accessions Reveals Genetic Variation and Genes Associated with Fiber Strength and Lint Percentage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3249–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Feng, L.; Deng, H.; Ji, X.; Zhang, J.; Sun, Y.; Lin, P.; Qiao, Y.; Xie, S.; Wang, H.; et al. Genomic Resequencing Reveals Genetic Diversity, Population Structure, and Core Collection of Durian Germplasm. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.I.; Heuberger, M.; Schoen, A.; Koo, D.H.; Quiroz-Chavez, J.; Adhikari, L.; Raupp, J.; Cauet, S.; Rodde, N.; Cravero, C.; et al. Einkorn Genomics Sheds Light on History of the Oldest Domesticated Wheat. Nature 2023, 620, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.P.; Fan, G.; Yin, P.P.; Sun, S.; Li, N.; Hong, X.; Hu, G.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.M.; Han, J.D.; et al. Resequencing 545 Ginkgo Genomes across the World Reveals the Evolutionary History of the Living Fossil. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Duan, S.; Sheng, J.; Zhu, S.; Ni, X.; Shao, J.; Liu, C.; Nick, P.; Du, F.; Fan, P.; et al. Whole-Genome Resequencing of 472 Vitis Accessions for Grapevine Diversity and Demographic History Analyses. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Ridout, K.; Serrano-Serrano, M.L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, A.; Ravikanth, G.; Nawaz, M.A.; Mumtaz, A.S.; et al. Large-Scale Whole-Genome Resequencing Unravels the Domestication History of Cannabis Sativa. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; van Treuren, R.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Dong, S.; Sun, P.; Yang, T.; Lan, T.; et al. Whole-Genome Resequencing of 445 Lactuca Accessions Reveals the Domestication History of Cultivated Lettuce. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 752–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, A.; Lire, H.; Higgins, J.; Olango, T.M.; Habte, E.H.; Negawo, A.T.; Muktar, M.S.; Assefa, Y.; Pereira, J.F.; Azevedo, A.L.S.; et al. Whole-Genome Resequencing of a Global Collection of Napier Grass (Cenchrus purpureus) to Explore Global Population Structure and QTL Governing Yield and Feed Quality Traits. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2025, 15, jkaf113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, J.; Sun, H.; Xiong, C.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jarret, R.; Wang, J.; Tang, B.; et al. Genomes of Cultivated and Wild Capsicum Species Provide Insights into Pepper Domestication and Population Differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zi, H.; Wei, H.; Cao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. Populus Cathayana Genome and Population Resequencing Provide Insights into Its Evolution and Adaptation. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhad255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Shen, E.; Hu, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, Y.; Lao, S.; Dong, C.; Du, T.; Hua, W.; Ye, C.Y.; et al. Population Genomic Analysis Reveals Domestication of Cultivated Rye from Weedy Rye. Mol. Plant 2022, 15, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatybekov, A.; Genievskaya, Y.; Fang, C.; Abugalieva, S.; Turuspekov, Y. Uncovering the Genetic Landscape of Soybean Accessions from Kazakhstan in Comparison with Global Germplasm Using Whole Genome Resequencing. BMC Genom. 2025, 26, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Ding, J.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Jiao, F.; Yang, L. Whole Genome Re-Sequencing in 437 Tobacco Germplasms Identifies Plant Height Candidate Genes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razifard, H.; Ramos, A.; Della Valle, A.L.; Bodary, C.; Goetz, E.; Manser, E.J.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Visa, S.; Tieman, D.; et al. Genomic Evidence for Complex Domestication History of the Cultivated Tomato in Latin America. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.K.; Rathore, A.; Bohra, A.; Yadav, P.; Das, R.R.; Khan, A.W.; Singh, V.K.; Chitikineni, A.; Singh, I.P.; Kumar, C.V.S.; et al. Development and Application of High-Density Axiom Cajanus SNP Array with 56K SNPs to Understand the Genome Architecture of Released Cultivars and Founder Genotypes. Plant Genome 2018, 11, 180005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, Y.; Ferrante, S.P.; Wu, G.A.; Federici, C.T.; Roose, M.L. Development and Assessment of SNP Genotyping Arrays for Citrus and Its Close Relatives. Plants 2024, 13, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wong, D.; Forrest, K.; Allen, A.; Chao, S.; Huang, B.E.; Maccaferri, M.; Salvi, S.; Milner, S.G.; Cattivelli, L.; et al. Characterization of Polyploid Wheat Genomic Diversity Using a High-Density 90 000 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Array. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaFramboise, T. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Arrays: A Decade of Biological, Computational and Technological Advances. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 4181–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burridge, A.J.; Winfield, M.; Przewieslik-Allen, A.; Edwards, K.J.; Siddique, I.; Barral-Arca, R.; Griffiths, S.; Cheng, S.; Huang, Z.; Feng, C.; et al. Development of a next Generation SNP Genotyping Array for Wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2235–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniguti, C.H.; Lau, J.; Hochhaus, T.; Arias, D.C.L.; Hokanson, S.C.; Zlesak, D.C.; Byrne, D.H.; Klein, P.E.; Riera-Lizarazu, O. Exploring Chromosomal Variations in Garden Roses: Insights from High-Density SNP Array Data and a New Tool, Qploidy. Plant Genome 2025, 18, e70044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganal, M.W.; Altmann, T.; Röder, M.S. SNP Identification in Crop Plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2009, 12, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble-Gagnère, G.; Pasam, R.; Forrest, K.L.; Wong, D.; Robinson, H.; Godoy, J.; Rattey, A.; Moody, D.; Mullan, D.; Walmsley, T.; et al. Novel Design of Imputation-Enabled SNP Arrays for Breeding and Research Applications Supporting Multi-Species Hybridization. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 756877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Yang, W.; Yang, Y.; Gong, J.; Yang, Q.Y.; Niu, X. Plant-ImputeDB: An Integrated Multiple Plant Reference Panel Database for Genotype Imputation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D1480–D1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Mauleon, R.; Hu, Z.; Chebotarov, D.; Tai, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, M.; Zheng, T.; Fuentes, R.R.; Zhang, F.; et al. Genomic Variation in 3,010 Diverse Accessions of Asian Cultivated Rice. Nature 2018, 557, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Wen, W.; Warburton, M.L.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Yang, X. Population Genomics of Zea Species Identifies Selection Signatures during Maize Domestication and Adaptation. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, L.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, N.; Chen, F. The Wheat 660K SNP Array Demonstrates Great Potential for Marker-Assisted Selection in Polyploid Wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1354–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, M.; Liang, L.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Liang, J.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, F.; et al. Rice3K56 Is a High-Quality SNP Array for Genome-Based Genetic Studies and Breeding in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Crop. J. 2023, 11, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Hyten, D.L.; Jia, G.; Quigley, C.V.; Fickus, E.W.; Nelson, R.L.; Cregan, P.B. Development and Evaluation of SoySNP50K, a High-Density Genotyping Array for Soybean. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrechtsen, A.; Nielsen, F.C.; Nielsen, R. Ascertainment Biases in SNP Chips Affect Measures of Population Divergence Research Article. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 2534–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geibel, J.; Reimer, C.; Weigend, S.; Weigend, A.; Pook, T.; Simianer, H. How Array Design Creates SNP Ascertainment Bias. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokan, K.; Kawamura, S.; Teshima, K.M. Effects of Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Ascertainment on Population Structure Inferences. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2021, 11, jkab128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Pan, H.; Yin, H. Decoding Hybrid Origins and Genetic Architecture of Leaf Traits Variation in Camellia via High-Density 21 K SNP Array for Genomic Prediction. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiscus, C.J.; Herniter, I.A.; Tchamba, M.; Paliwal, R.; Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Roberts, P.A.; Abberton, M.; Alaba, O.; Close, T.J.; Oyatomi, O.; et al. The Pattern of Genetic Variability in a Core Collection of 2,021 Cowpea Accessions. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2024, 14, jkae071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, T.; You, E.; Bian, H.; Chen, W.; Zhang, B.; Shen, Y. Population Structure Analysis and Genome-Wide Association Study of a Hexaploid Oat Landrace and Cultivar Collection. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1131751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koorevaar, T.; Willemsen, J.H.; Visser, R.G.F.; Arens, P.; Maliepaard, C. Construction of a Strawberry Breeding Core Collection to Capture and Exploit Genetic Variation. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, J.P.; Li, C.; Buell, C.R. The Rice Genome Annotation Project: An Updated Database for Mining the Rice Genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1614–D1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, E.; Schmutzer, T.; Barilar, I.; Mascher, M.; Gundlach, H.; Martis, M.M.; Twardziok, S.O.; Hackauf, B.; Gordillo, A.; Wilde, P.; et al. Towards a Whole-Genome Sequence for Rye (Secale cereale L.). Plant J. 2017, 89, 853–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseneyer, G.; Schmutzer, T.; Seidel, M.; Zhou, R.; Mascher, M.; Schön, C.-C.; Taudien, S.; Scholz, U.; Stein, N.; Mayer, K.F.; et al. From RNA-Seq to Large-Scale Genotyping—Genomics Resources for Rye (Secale cereale L.). BMC Plant Biol. 2011, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.G.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Vetriventhan, M.; Buckler, E.S.; Tom Hash, C.; Ramu, P. The Genetic Makeup of a Global Barnyard Millet Germplasm Collection. Plant Genome 2015, 8, plantgenome2014.10.0067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharajan, T.; Krishna, T.P.A.; Krishnakumar, N.M.; Vetriventhan, M.; Kudapa, H.; Ceasar, S.A. Role of Genome Sequences of Major and Minor Millets in Strengthening Food and Nutritional Security for Future Generations. Agriculture 2024, 14, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renganathan, V.G.; Vanniarajan, C.; Karthikeyan, A.; Ramalingam, J. Barnyard Millet for Food and Nutritional Security: Current Status and Future Research Direction. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clevenger, J.; Chavarro, C.; Pearl, S.A.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Jackson, S.A. Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Identification in Polyploids: A Review, Example, and Recommendations. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limborg, M.T.; Seeb, L.W.; Seeb, J.E. Sorting Duplicated Loci Disentangles Complexities of Polyploid Genomes Masked by Genotyping by Sequencing. Mol. Ecol. 2016, 25, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, P.M.; Voorrips, R.E.; Visser, R.G.F.; Maliepaard, C. Tools for Genetic Studies in Experimental Populations of Polyploids. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucker, B.; Irisarri, I.; De Vries, J.; Xu, B. Plant Genome Sequence Assembly in the Era of Long Reads: Progress, Challenges and Future Directions. Quant. Plant Biol. 2022, 3, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladman, N.; Goodwin, S.; Chougule, K.; Richard McCombie, W.; Ware, D. Era of Gapless Plant Genomes: Innovations in Sequencing and Mapping Technologies Revolutionize Genomics and Breeding. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2023, 79, 102886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della Coletta, R.; Qiu, Y.; Ou, S.; Hufford, M.B.; Hirsch, C.N. How the Pan-Genome Is Changing Crop Genomics and Improvement. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayer, P.E.; Golicz, A.A.; Scheben, A.; Batley, J.; Edwards, D. Plant Pan-Genomes Are the New Reference. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Tian, Z.; Lai, J.; Huang, X. Plant Pan-Genomics and Its Applications. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Goltsman, E.; Goodstein, D.; Wu, G.A.; Rokhsar, D.S.; Vogel, J.P. Plant Pan-Genomics Comes of Age. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, H.S.; Lee, H.T.; Gabur, I.; Vollrath, P.; Tamilselvan-Nattar-Amutha, S.; Obermeier, C.; Schiessl, S.V.; Song, J.M.; Liu, K.; Guo, L.; et al. Long-Read Sequencing Reveals Widespread Intragenic Structural Variants in a Recent Allopolyploid Crop Plant. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, V.; Vetriventhan, M.; Senthil, R.; Geetha, S.; Deshpande, S.; Rathore, A.; Kumar, V.; Singh, P.; Reddymalla, S.; Azevedo, V.C.R. Genome-Wide DArTSeq Genotyping and Phenotypic Based Assessment of Within and Among Accessions Diversity and Effective Sample Size in the Diverse Sorghum, Pearl Millet, and Pigeonpea Landraces. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 587426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano-Duque, L.F.; Bejarano-Garavito, D.; Castillo-Sierra, J.; Torres-Cuesta, D.R.; Cortés, A.J.; Blair, M.W. SNP Genotyping for Purity Assessment of a Forage Oat (Avena sativa L.) Variety from Colombia. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkner, M.O.; Jiang, Y.; Reif, J.C.; Schulthess, A.W. Trait-Customized Sampling of Core Collections from a Winter Wheat Genebank Collection Supports Association Studies. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1451749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, P.; Alachiotis, N. A Survey of Methods and Tools to Detect Recent and Strong Positive Selection. J. Biol. Res. 2017, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhou, A.; Sang, T. Rice Domestication by Reducing Shattering. Science 2006, 311, 1936–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frary, A.; Nesbitt, T.C.; Frary, A.; Grandillo, S.; Van Der Knaap, E.; Cong, B.; Liu, J.; Meller, J.; Elber, R.; Alpert, K.B.; et al. Fw2.2: A Quantitative Trait Locus Key to the Evolution of Tomato Fruit Size. Science 2000, 289, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccaferri, M.; Harris, N.S.; Twardziok, S.O.; Pasam, R.K.; Gundlach, H.; Spannagl, M.; Ormanbekova, D.; Lux, T.; Prade, V.M.; Milner, S.G.; et al. Durum Wheat Genome Highlights Past Domestication Signatures and Future Improvement Targets. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegary, D.; Teklewold, A.; Prasanna, B.M.; Ertiro, B.T.; Alachiotis, N.; Negera, D.; Awas, G.; Abakemal, D.; Ogugo, V.; Gowda, M.; et al. Molecular Diversity and Selective Sweeps in Maize Inbred Lines Adapted to African Highlands. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndjiondjop, M.N.; Alachiotis, N.; Pavlidis, P.; Goungoulou, A.; Kpeki, S.B.; Zhao, D.; Semagn, K. Comparisons of Molecular Diversity Indices, Selective Sweeps and Population Structure of African Rice with Its Wild Progenitor and Asian Rice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semagn, K.; Iqbal, M.; Alachiotis, N.; N’Diaye, A.; Pozniak, C.; Spaner, D. Genetic Diversity and Selective Sweeps in Historical and Modern Canadian Spring Wheat Cultivars Using the 90K SNP Array. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narum, S.R.; Hess, J.E. Comparison of FST Outlier Tests for SNP Loci under Selection. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2011, 11, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Yu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lun, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Genomic Analyses Provide Insights into the History of Tomato Breeding. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca, J.; Montero-Pau, J.; Sauvage, C.; Bauchet, G.; Illa, E.; Díez, M.J.; Francis, D.; Causse, M.; van der Knaap, E.; Cañizares, J. Genomic Variation in Tomato, from Wild Ancestors to Contemporary Breeding Accessions. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Q.; Yang, X.; Peng, Z.; Xu, L.; Wang, J. Development and Applications of a High Throughput Genotyping Tool for Polyploid Crops: Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Array. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, S.F.; Bayer, P.E.; Wells, R.; Snowdon, R.J.; Batley, J.; Varshney, R.K.; Nguyen, H.T.; Edwards, D.; Golicz, A.A. Pangenomics in Crop Improvement—From Coding Structural Variations to Finding Regulatory Variants with Pangenome Graphs. Plant Genome 2022, 15, e20177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, Z.; Li, H.; Lyu, Y.; Zan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, L.; Fang, Y.; Wu, K.; et al. Graph Pangenome Captures Missing Heritability and Empowers Tomato Breeding. Nature 2022, 606, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gage, J.L.; Vaillancourt, B.; Hamilton, J.P.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.C.; Gustafson, T.J.; Barry, K.; Lipzen, A.; Tracy, W.F.; Mikel, M.A.; Kaeppler, S.M.; et al. Multiple Maize Reference Genomes Impact the Identification of Variants by Genome-Wide Association Study in a Diverse Inbred Panel. Plant Genome 2019, 12, 180069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves-Dias, J.; Stetter, M.G. PopAmaranth: A Population Genetic Genome Browser for Grain Amaranths and Their Wild Relatives. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2021, 11, jkab103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Mahato, A.K.; Maurya, A.; Rajkumar, S.; Singh, A.K.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kaushik, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Gupta, V.; Singh, K.; et al. Amaranth Genomic Resource Database: An Integrated Database Resource of Amaranth Genes and Genomics. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1203855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, F.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, P.; Song, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; et al. A Genome Variation Map Provides Insights into the Genetics of Walnut Adaptation and Agronomic Traits. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuno, S.; Ralph, P.; Swarts, K.; Elshire, R.J.; Glaubitz, J.C.; Buckler, E.S.; Hufford, M.B.; Ross-Ibarra, J. Independent Molecular Basis of Convergent Highland Adaptation in Maize. Genetics 2015, 200, 1297–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsoglou, E.A.; Faria, D.; Arend, D.; Arnaud, E.; Athanasiadis, I.N.; Chaves, I.; Coppens, F.; Cornut, G.; Costa, B.V.; Ćwiek-Kupczyńska, H.; et al. Enabling Reusability of Plant Phenomic Datasets with MIAPPE 1.1. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, M.; Iqra, F.; Ambreen, H.; Pravin, K.A.; Ikra, M.; Chung, Y.S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and High-Throughput Phenotyping for Crop Improvement. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 1787–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Yang, W.; Zhao, C. High-Throughput Phenotyping: Breaking through the Bottleneck in Future Crop Breeding. Crop J. 2021, 9, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hao, J.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, F.; Mur, L.A.J.; Han, Y.; Hou, S.; Han, J.; et al. Integrating Dynamic High-Throughput Phenotyping and Genetic Analysis to Monitor Growth Variation in Foxtail Millet. Plant Methods 2024, 20, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.K.; Sarkar, S. Machine Learning for High-Throughput Stress Phenotyping in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmley, K.A.; Higgins, R.H.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Sarkar, S.; Singh, A.K. Machine Learning Approach for Prescriptive Plant Breeding. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X. Single-Cell and Spatial Multi-Omics in the Plant Sciences: Technical Advances, Applications, and Perspectives. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Y.; Pujol, V.; Staut, J.; Pollaris, L.; Seurinck, R.; Eekhout, T.; Grones, C.; Saura-Sanchez, M.; Van Bel, M.; Vuylsteke, M.; et al. A Single-Cell and Spatial Wheat Root Atlas with Cross-Species Annotations Delineates Conserved Tissue-Specific Marker Genes and Regulators. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weckwerth, W.; Ghatak, A.; Bellaire, A.; Chaturvedi, P.; Varshney, R.K. PANOMICS Meets Germplasm. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1507–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genotyping Approach | Platform | Polymorphism Detection Capacity | Type of Polymorphism Detected | Reference Genome Required | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRS * | GBS DArTseq RAD-seq SLAF-seq | Thousands to hundreds of thousands of SNPs | SNPs PAV(some platforms) | No | Cost-effective. No need for prior SNP information. Works across any genome size and any species. Ideal for non-model and orphan species. | Demands higher computational skills and QC than arrays. Mapping bias. Difficulty distinguishing homologous vs. homoeologous loci in high-ploidy species. Reproducibility is protocol-dependent. |

| WGRS | Low-coverage-Illumina based Long-read-sequencing based | Millions to hundreds of millions of SNPs | SNPs InDels CNV SVs PAV | Yes | Discovery of various types of polymorphism (SNPs, InDels, CNV, SVs). Survey of polymorphism across the whole genome. | Requires a reference genome sequence (or transcriptome). Demands specialised bioinformatic skills. More expensive compared to RRS and SNP arrays. |

| SNP arrays | Illumina Infinium (iSelect/BeadChip) Thermofisher Axiom | iSelect HD: 3 k to 90 k iSelect HTS: 90 k to 700 k Up to 2.6 million | SNPs InDels CNV SVs PAV | Yes | Accurate genotyping in polyploid species. Straightforward downstream analysis. High reproducibility and accuracy of genotyping calls. Same SNP calls remain stable across breeding programmes and years | No novel variant discovery. Reduced power to detect marker-trait association Skewed allele frequencies Biased representation of genetic variations |

| Organism | RRS Variant | No. of Accessions | Institution, Country, Where Germplasm Is Kept | No. of Polymorphic Loci | Analyses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African mahogany | GBS | 115 | forest plantations in the Reserva Natural Vale and Viveiro Origem, Brasil | 3.3 k | diversity assessment, population structure | [59] |

| amaranth | GBS | 192 | National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources, India | 42 k | phylogeny, population structure | [60] |

| apricot | RAD-seq | 168 | Luntai National Fruit Germplasm Resources Garden; Yingjisha County Apricot National Forest Germplasm Bank; Xiongyue National Germplasm Resources Garden, China | 418 k | population structure, gene flow selection scan | [61] |

| avocado | GBS | 384 | Colombian Germplasm Bank; Seedling Rootstocks (SR) (n = 240) of commercial orchards from the northwest Andes; Colombia | 4.9 k | diversity assessment, population structure, phylogeny | [62] |

| banana | DArTseq | 856 | International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda; National Agriculture Research Organization, Uganda; Embrapa, Brasil; National Research Centre for Banana, India; International Transit Centre, Belgium | 6.1–19.7 k | diversity assessment, population structure | [63] |

| barley | GBS | 22.6 k | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Germany; National Crop Genebank of China, China; Agroscope, Switzerland | 170 k | population structure GWAS redundancy | [64] |

| blueberry | GBS | 195 | Philip E. Marucci Center for Blueberry & Cranberry Research and Extension, State University of New Jersey, USA | 60.5 k | Population structure, gene flow, section scan | [65] |

| canola | GBS | 433 | Kansas State University, USA | 251.5 k | population structure | [66] |

| Capsicum | GBS | 283 | AGROSAVIA La Selva Research Station, Colombia | 68.5 k; 30 k | population structure, GWAS | [67] |

| cassava | DArTseq | 5.3 k | International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Colombia | 7 k | redundancy | [7] |

| common bean | GBS | 78 | International Center for Tropical Agriculture, Colombia | 23.3 k | kinship, population structure, GWAS | [68] |

| Crotolaria | GBS | 80 | Genetic Resources Research Institute of Kenya, Kenya | 9.8 k | diversity assessment, phylogeny, population structure | [69] |

| faba bean | GBS | 217 | ICARDA genebank, Lebanon | 40 k | linkage mapping GWAS | [52] |

| foxtail lily | GBS | 96 | wild Eremurus populations in Iran | 3 k | phylogeny, population structure | [70] |

| melon | GBS | 755 | National Agriculture and Food Research Organization, Japan | 39.3 k | diversity assessment, population structure, core subset selection | [71] |

| oat | GBS | 9112 | Multiple institutions | 19.9 k | population structure, structural rearrangements | [72] |

| oil palm | GBS | 478 | Malaysian Palm Oil Board Research Station, Malaysia | 7 k | population structure, core subset selection | [73] |

| peas | DArTseq | 325 | Instituto de Agricultura Sostenible, Spain | 35.8 k | phylogeny, population structure LD scan | [74] |

| phalaenopsis | GBS | 116 | National Cheng Kung University, China | 113.5 k | GWAS | [75] |

| potato | GBS | 730 | US potato genebank, Sturgeon Bay, USA | 7.8 k | ploidy estimation, population structure, core subset selection | [76] |

| rye | DArTseq | 478 | Several genebanks, universities and breeding companies | 12.8 k | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan | [77] |

| sesame | GBS | 501 | US Department of Agriculture sesame collection, USDA-ARS Plant Genetic Resources Conservation Unit, USA | 24.7 k | phylogeny, population structure, LD scan | [78] |

| sunflower | RAD seq | 135 | Active Germplasm Bank of Instituto Nacional de Tecnología Agropecuaria Manfredi, Argentina | 11.8 k | diversity assessment, population structure, LD scan | [79] |

| quinoa | GBS | 136 | Germplasm Resources Information Network of the US Department of Agriculture, USA | 5.7 k | phylogeny, population structure, LD scan | [80] |

| wheat | DArTseq | 80 k | International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, Morroco | 40 k | population structure, redundancy, core subset selection, selection scan, GWAS, | [81] |

| yam | DArTseq | 100 | International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Nigeria | 7 k | population structure | [82] |

| Organism | Coverage (Approx.) | No. of Accessions | Institution, Country, Where Germplasm Is Kept | No. of Polymorphic Loci Detected/(Used) | Analyses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| amaranth | not specified | 108 | US Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service genebank, USA | 1.4 M | gene flow, selection scan | [101] |

| avocado | 4.69× | 205 | Avocado ‘Plus Tree’ Collection; Arangro Plant Nursery; Colombian Germplasm Bank, Colombia | 64 M | phylogeny, population structure, racial tracing | [102] |

| carrot | not specified | 630 | Germplasm Resources Information Network of the US Department of Agriculture, USA | 5.4 M (168 k) | population structure, selection scan, GWAS | [103] |

| chickpea | 12× | 3366 | International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, India; International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, Lebanon | 23.5 M | GWAS, LD scan, selection scan | [29] |

| coffee | not specified | 90 | Choche germplasm bank of the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute, Etiopia | 11 M | phylogeny | [104] |

| common bean | not specified | 144 | International Centre for Tropical Agriculture, Colombia; Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Germany; JungleSeeds, Betchworth, UK; Beans and Beans, Horningsham, UK | 20.2 M | population structure, phylogeny, GWAS | [105] |

| cotton | 10.85× | 240 | Zhejiang University, China | 3.8 M | phylogeny, population structure, GWAS | [106] |

| durian | 114 | cultivations sites in Hainan and Yunnan, China | 39 M | diversity assessment, population structure, LD scan, selection scan, core subset selection | [107] | |

| einkorn | not specified | 219 | Wheat Genetics Resource Center, USA | 121 M | phylogeny, population structure | [108] |

| ginkgo | 6.3× | 525 | Trees growing in multiple locations in China, Japan, Korea USA and Europe | 160 M | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan | [109] |

| grapevine | 15.5× | 472 | Chinese Academy of Sciences; Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China; Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany | 38.7 M | phylogeny, population structure, LD scan, pedigree analysis, selection scan, GWAS | [110] |

| hemp | 10× | 110 | Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources, Russia; various companies | 12 M | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan | [111] |

| lettuce | 18.8× | 445 | Centre for Genetic Resources, the Netherlands | 208 M | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan, GWAS | [112] |

| napier grass | 15–20× | 450 | International Livestock Research Institute, Ethiopia; Embrapa, Brasil; US Department of Agriculture, USA; Kenya Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization, Kenya; Lanzhou University, China | 170 M (1 M) | diversity assessment, GWAS | [113] |

| pepper | 14.7× | 500 | U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, USA; Hunan Academy of Agricultural Science, China | 1005 M (29 k) | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan | [114] |

| Populus cathayana | 32.3× | 438 | Chinese Academy of Forestry, China | 12.3 M | population structure, selection scan, GEA analysis | [115] |

| rye | 10× | 116 | Germplasm Resources Information Network, USA; Institute of Crop Science, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, and other collections | 908.6 k | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan | [116] |

| rye | not specified | 94 | Several genebanks, universities and breeding companies | 2.5 M | gene variants | [26] |

| soybean | not specified | 684 | Institute of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Kazakhstan; Guangzhou University, China | 8 M (81 k) | phylogeny, population structure | [117] |

| tobacco | 13× | 437 | Yunnan Academy of Tobacco Agricultural Sciences, China | 2.2 M | phylogeny, population structure, gene flow, GWAS | [118] |

| tomato | not specified | 295 | Polytechnic University of Valencia, Spain | 28 M (18 M; 8.8 M; 162 k) | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan, LD scan, GWAS | [119] |

| quinoa | 7.8× | 303 | Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Germany; U.S. National Plant Germplasm System, USA | 2.9 M | phylogeny, population structure, LD scan, GWAS | [25] |

| Organism | Array Name | No. of Accessions | Institution, Country, Where Germplasm Is Kept | No. of Polymorphic Loci | Analyses | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| camellia | Camelia21K | 69 | Camellia Germplasm 479 Resource Conservation Center of the Research Institute of Subtropical Forestry, China | 19.3 k | phylogeny, population structure, GWAS | [137] |

| citrus | 1.4 M SNP Axiom® HD Citrus genotyping array | 196 | Citrus Variety Collection, USA | 729 k | population structure | [121] |

| citrus | 58 K Axiom® Citrus genotyping array | 871 | Citrus Variety Collection, USA | 43 k | phylogeny, population structure | [121] |

| cowpea | Illumina Cowpea iSelect Consortium Array | 2201 | International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Nigeria | 48 k | population structure, LD scan, GWAS | [138] |

| maize, teosinte | Illumina MaizeSNP50 BeadChip | 1172 | maize breeding programs of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (Mexico), China, USA, Thailand, and Peru | 42.2 k | phylogeny, population structure, selection scan, GWAS | [130] |

| oat | iSelect 6 K-beadchip | 288 | USDA National Small Grain Collection, USA | 2213 | population structure, LD scan, GWAS | [139] |

| pigeonpea | Axiom Cajanus SNP array | 103 | International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, India | 51.2 k | phylogeny, population structure | [120] |

| rice | Rice3K56 | 192 | Anhui Agricultural University, China | not specified | phylogeny, varietal identification, GWAS | [132] |

| soybean | SoySNP50K | 286 | United States Department of Agriculture, USA | 47 k | selection scan | [133] |

| strawberry | Istraw35 | 891 | The strawberry breeding program at Fresh Forward B.V., Huissen, The Netherlands | 30 k | core subset selection | [140] |

| wheat | TaNGv1.1 | 908 | Germplasm Resources Unit at the John Innes Centre, UK; USDA Germplasm Resource Information Network, USA; Nations BioResource Project-Wheat genebank, Japan | 42.5 k | linkage mapping, CNV analysis, GWAS | [124] |

| Factors | Methods | Comments | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRS | WGRS | SNP arrays | ||

| Main research objectives | ||||

| 1. Diversity/population structure | ++++ | ++++ | ++ * | * May not work for genetically diverse populations. |

| 2. Novel variant discovery | ++ * | ++++ | + ** | * RRS enables partial variant discovery. ** SNP arrays enable none. |

| 3. GWAS/Genome prediction | +++ | ++ * | ++++ ** | * Too expensive because a large number of samples are needed for GWAS. ** The best choice due to high reproducibility and low missing data. |

| 4. Selection scans | ++ * | ++++ | + ** | * Weak for haplotype-based scans. ** Ascertainment bias. |

| Available resources | ||||

| 1. Reference genome | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | |

| 2. SNP arrays | ++ * | +++ ** | ++++ | * No reason to choose it over arrays unless you want more discovery. ** Choose it only when full genome resolution is required. |

| 3. None | ++++ | ++ * | - | * A de novo genome assembly is required |

| What is the available budget? | ||||

| 1. Low | ++++ | - | ++++ * | * If SNP arrays are available |

| 2. Medium | ++++ | ++ * | ++++ ** | * Lower coverage WGRS. ** Cost depends on marker density and whether the array is commercial or custom. |

| 3. High | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | When budget is not a concern, the choice of method depends primarily on the study purpose and sample size. |

| What is the species’ ploidy? | ||||

| 1. Diploid | ++++ | ++++ | ++++ | Diploid species tolerate all methods well |

| 2. Polyploid | +++ * | ++++ | ++ ** | * RRS is only reliable with fully aware polyploidy pipelines. ** SNP arrays are reliable only if designed for that ploidy level. |

| Cross-study comparability | ++ * | +++ ** | ++++ *** | * Missing data causes low overlap between SNPs in different studies. ** Only if using the same reference and pipeline. *** Data is consistent across labs, years, and experiments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Werghi, S.; Koboyi, B.W.; Chan-Rodriguez, D.; Bolibok-Brągoszewska, H. Genome-Wide, High-Density Genotyping Approaches for Plant Germplasm Characterisation (Methods and Applications). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411833

Werghi S, Koboyi BW, Chan-Rodriguez D, Bolibok-Brągoszewska H. Genome-Wide, High-Density Genotyping Approaches for Plant Germplasm Characterisation (Methods and Applications). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411833

Chicago/Turabian StyleWerghi, Sirine, Brian Wakimwayi Koboyi, David Chan-Rodriguez, and Hanna Bolibok-Brągoszewska. 2025. "Genome-Wide, High-Density Genotyping Approaches for Plant Germplasm Characterisation (Methods and Applications)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411833

APA StyleWerghi, S., Koboyi, B. W., Chan-Rodriguez, D., & Bolibok-Brągoszewska, H. (2025). Genome-Wide, High-Density Genotyping Approaches for Plant Germplasm Characterisation (Methods and Applications). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11833. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411833