Molecular Crossroads: Shared and Divergent Molecular Signatures in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies

Abstract

1. Introduction

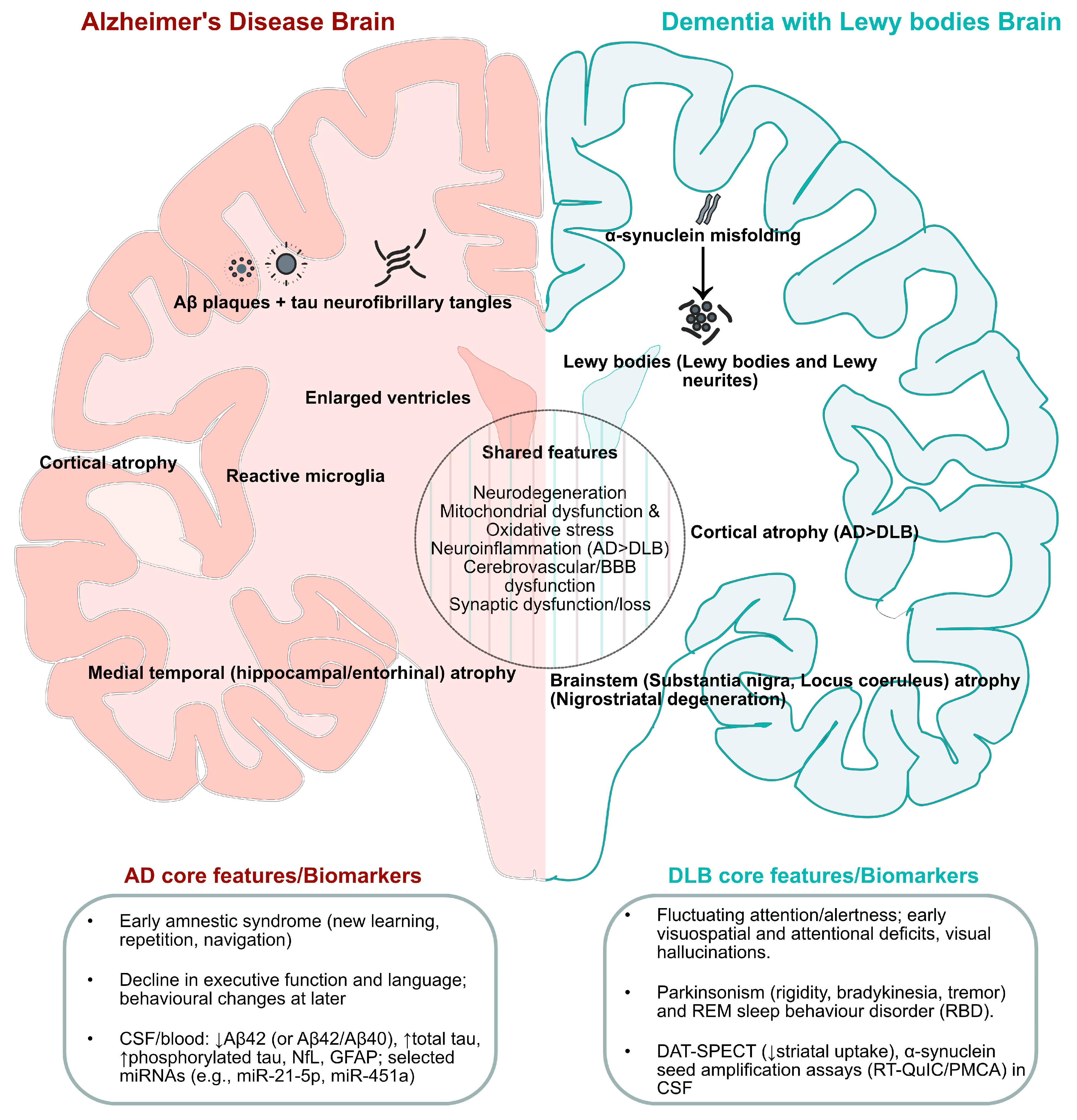

2. Clinical and Neuropathological Overlap Between AD and DLB

2.1. Clinical Features of AD

2.2. Clinical Features of DLB

2.3. Neuropathological Features of AD

2.4. Neuropathological Features of DLB

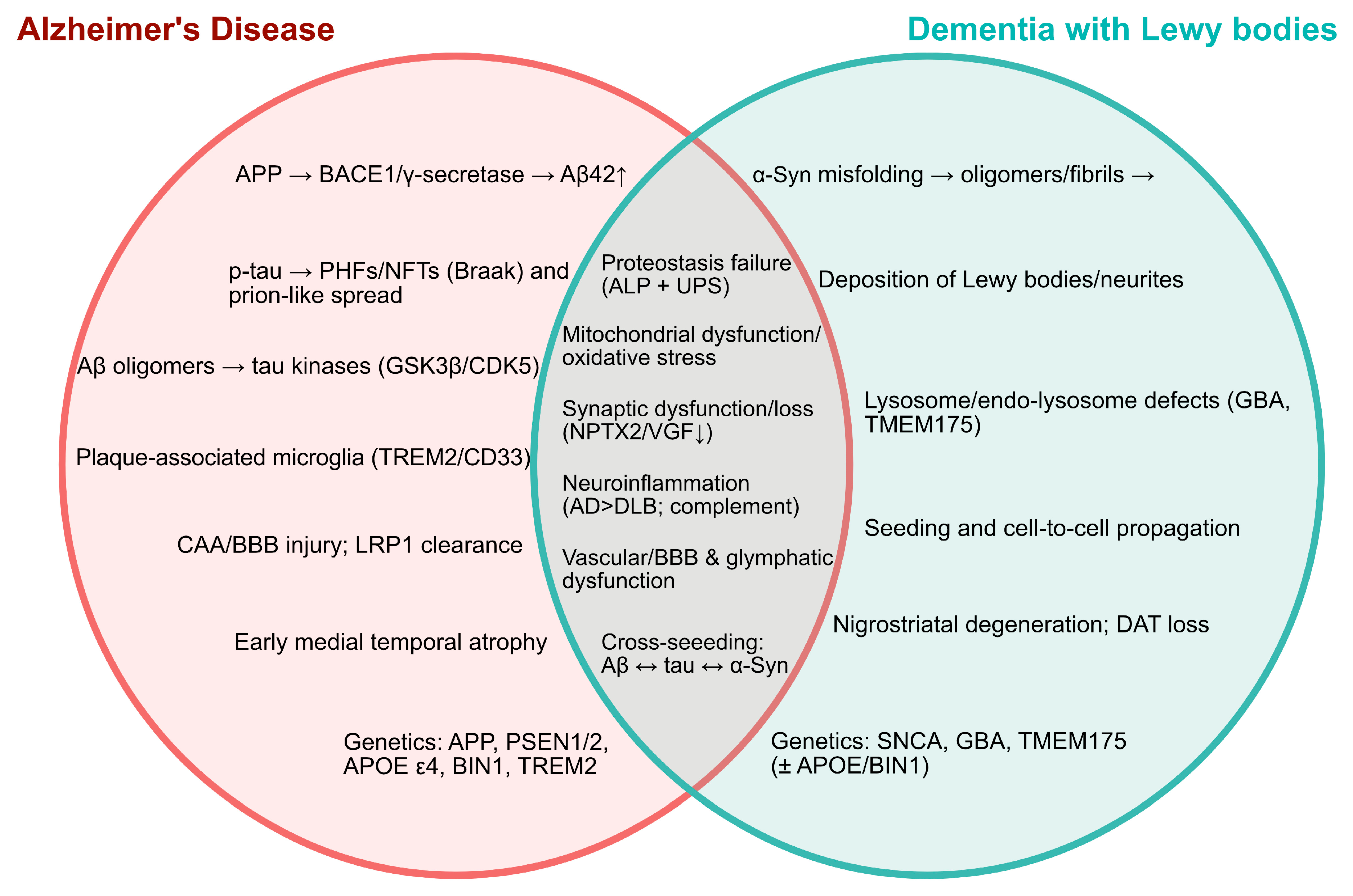

3. Shared and Divergent Molecular Pathways

3.1. From Etiology to Genetics: AD Versus DLB

3.2. Pathogenic Frameworks: Aβ/Tau/Cholinergic Hypotheses in AD and α-Syn Pathology in DLB

3.3. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress in AD Versus DLB

3.4. Neuroinflammation and Cerebrovascular/Endothelial Dysfunction in AD and DLB

3.5. Emerging Pathways from Multi-Omics of AD and DLB

4. Emerging Next-Generation Biomarkers

5. Conclusions and Therapeutic Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 18F-FDG | 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose |

| A/T(N) | amyloid/tau/neurodegeneration |

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADNI | Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative |

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BACE1 | β-site APP cleaving enzyme 1 |

| CAA | cerebral amyloid angiopathy |

| CSF | cerebrospinal fluid |

| CTF99 | C-terminal fragment 99 (of APP) |

| DALY | disability-adjusted life year |

| DAT-SPECT | dopamine transporter single-photon emission computed tomography |

| DLB | dementia with Lewy bodies |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GWAS | genome-wide association studies |

| iPSC | induced pluripotent stem cells |

| LBD | Lewy body disease |

| LBV | Lewy body variant (of Alzheimer’s disease) |

| LMTK2 | Lemur Tyrosine Kinase 2 |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAPT | microtubule-associated protein tau |

| MIBG | metaiodobenzylguanidine |

| miR | microRNA |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MSA | multiple system atrophy |

| NfL | neurofilament light chain |

| NIA–AA | National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association |

| NINCDS–ADRDA | National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PDD | Parkinson’s disease dementia |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PFF | pre-formed fibril |

| PheWASs | phenome-wide association studies |

| PMCA | Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification |

| RBD | REM sleep behaviour disorder |

| REM | rapid eye movement |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| RT-QuIC | real-time quaking-induced conversion |

| SAA(s) | seed amplification assays |

| SPECT | single-photon emission computed tomography |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| TMT-MS | Tandem Mass Tag mass spectrometry |

| α-Syn | alpha-synuclein |

References

- Hippius, H.; Neundörfer, G. The Discovery of Alzheimer’s Disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 5, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakor, V.S.; Tyagi, A.; Lee, J.M., Jr.; Coffman, F.; Mittal, R. Alois Alzheimer (1864–1915): The Father of Modern Dementia Research and the Discovery of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e71731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.D.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.B.; Young, L.D. History of Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Neurocognitive Disord. 2016, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurea, V.A.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Mohan, A.G.; Costin, H.P.; Voicu, V. Alzheimer’s Disease: 120 Years of Research and Progress. JMedLife 2023, 16, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care: 2020 Report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446, Erratum in Lancet 2023, 402, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaopeng, Z.; Jing, Y.; Xia, L.; Xingsheng, W.; Juan, D.; Yan, L.; Baoshan, L. Global Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias in Adults Aged 65 Years and Older, 1991–2021: Population-Based Study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1585711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Seeher, K.M.; Schiess, N.; Nichols, E.; Cao, B.; Servili, C.; Cavallera, V.; Cousin, E.; Hagins, H.; Moberg, M.E.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Disorders Affecting the Nervous System, 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Hou, N.; Han, F.; Liu, Y. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 1990–2019. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 937486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Zhai, Y.-J.; An, H.-H.; Wu, F.; Qiu, H.-N.; Li, J.-B.; Lin, J.-N. Global Trends in Prevalence, Disability Adjusted Life Years, and Risk Factors for Early Onset Dementia from 1990 to 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 13488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.-S.; Li, D.-J.; Yang, F.-C.; Tseng, P.-T.; Carvalho, A.F.; Stubbs, B.; Thompson, T.; Mueller, C.; Shin, J.I.; Radua, J.; et al. Mortality Rates in Alzheimer’s Disease and Non-Alzheimer’s Dementias: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021, 2, e479–e488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.; Dickerson, B.C.; Frost, C.; Jiskoot, L.C.; Wolk, D.; Van Der Flier, W.M. Alzheimer’s Disease First Symptoms Are Age Dependent: Evidence from the NACC Dataset. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015, 11, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Karaman, R. Comprehensive Review on Alzheimer’s Disease: Causes and Treatment. Molecules 2020, 25, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förstl, H.; Kurz, A. Clinical Features of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 249, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvěřová, M. Clinical Aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease. Clin. Biochem. 2019, 72, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trejo-Lopez, J.A.; Yachnis, A.T.; Prokop, S. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igarashi, K.M. Entorhinal Cortex Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Neurosci. 2023, 46, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacikowski, P.; Kalender, G.; Ciliberti, D.; Fried, I. Human Hippocampal and Entorhinal Neurons Encode the Temporal Structure of Experience. Nature 2024, 635, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, R.E.; Bertram, L. Twenty Years of the Alzheimer’s Disease Amyloid Hypothesis: A Genetic Perspective. Cell 2005, 120, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glenner, G.G.; Wong, C.W. Alzheimer’s Disease: Initial Report of the Purification and Characterization of a Novel Cerebrovascular Amyloid Protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984, 120, 885–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Tung, Y.-C.; Wisniewski, H.M. Alzheimer Paired Helical Filaments: Immunochemical Identification of Polypeptides. Acta Neuropathol. 1984, 62, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Tung, Y.C.; Quinlan, M.; Wisniewski, H.M.; Binder, L.I. Abnormal Phosphorylation of the Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau (Tau) in Alzheimer Cytoskeletal Pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4913–4917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capouch, S.D.; Farlow, M.R.; Brosch, J.R. A Review of Dementia with Lewy Bodies’ Impact, Diagnostic Criteria and Treatment. Neurol. Ther. 2018, 7, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedert, M.; Jakes, R.; Spillantini, M.G. The Synucleinopathies: Twenty Years On. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, S51–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outeiro, T.F.; Koss, D.J.; Erskine, D.; Walker, L.; Kurzawa-Akanbi, M.; Burn, D.; Donaghy, P.; Morris, C.; Taylor, J.-P.; Thomas, A.; et al. Dementia with Lewy Bodies: An Update and Outlook. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Crowther, R.A.; Jakes, R.; Hasegawa, M.; Goedert, M. α-Synuclein in Filamentous Inclusions of Lewy Bodies from Parkinson’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 6469–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Neuropathological Spectrum of Synucleinopathies. Mov. Disord. 2003, 18, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellinger, K.A.; Lantos, P.L. Papp–Lantos Inclusions and the Pathogenesis of Multiple System Atrophy: An Update. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Heterogeneity of Multiple System Atrophy: An Update. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvin, J.E.; Chrisphonte, S.; Cohen, I.; Greenfield, K.K.; Kleiman, M.J.; Moore, C.; Riccio, M.L.; Rosenfeld, A.; Shkolnik, N.; Walker, M.; et al. Characterization of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Mild Cognitive Impairment Using the Lewy Body Dementia Module (LBD-MOD). Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1675–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vann Jones, S.A.; O’Brien, J.T. The Prevalence and Incidence of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Systematic Review of Population and Clinical Studies. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakisaka, Y.; Furuta, A.; Tanizaki, Y.; Kiyohara, Y.; Iida, M.; Iwaki, T. Age-Associated Prevalence and Risk Factors of Lewy Body Pathology in a General Population: The Hisayama Study. Acta Neuropathol. 2003, 106, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnavel, A.; Dino, F.R.; Jiang, C.; Azmy, S.; Wyman-Chick, K.A.; Bayram, E. Risk Factors and Predictors for Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review. npj Dement. 2025, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Katta, M.R.; Abhishek, S.; Sridhar, R.; Valisekka, S.S.; Hameed, M.; Kaur, J.; Walia, N. Recent Advances in Lewy Body Dementia: A Comprehensive Review. Dis.-A-Mon. 2023, 69, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trétiakoff, K.N. Contribution à L’étude De L’anatomie Pathologique Du Locus Niger De Soemmering avec Quelques Deductions Relatives A La Pathogenie Des Troubles Du Tonus Musculaire et De La Maladie De Parkinson. Ph.D. Thesis, Universtié de Paris, Paris, France, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, H.; Lipkin, L.E.; Aronson, S.M. Diffuse Intracytoplasmic Ganglionic Inclusions (Lewy Type) Associated with Progressive Dementia and Quadriparesis in Flexion. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1961, 20, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, K.; Iseki, E. Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 1996, 9, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, K. Lewy Bodies in Cerebral Cortex. Report of Three Cases. Acta Neuropathol. 1978, 42, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Galasko, D.; Kosaka, K.; Perry, E.K.; Dickson, D.W.; Hansen, L.A.; Salmon, D.P.; Lowe, J.; Mirra, S.S.; Byrne, E.J.; et al. Consensus Guidelines for the Clinical and Pathologic Diagnosis of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB): Report of the Consortium on DLB International Workshop. Neurology 1996, 47, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C.; Ballard, C.; Corbett, A.; Aarsland, D. Historical Landmarks in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spillantini, M.G.; Schmidt, M.L.; Lee, V.M.-Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M. α-Synuclein in Lewy Bodies. Nature 1997, 388, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan, G.; Laczó, J.; Hort, J.; Minihane, A.-M.; Hornberger, M. Spatial Navigation Deficits—Overlooked Cognitive Marker for Preclinical Alzheimer Disease? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopman, D.S.; Amieva, H.; Petersen, R.C.; Chételat, G.; Holtzman, D.M.; Hyman, B.T.; Nixon, R.A.; Jones, D.T. Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2021, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKhann, G.; Drachman, D.; Folstein, M.; Katzman, R.; Price, D.; Stadlan, E.M. Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Report of the NINCDS—ADRDA Work Group under the Auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1984, 34, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKhann, G.M.; Knopman, D.S.; Chertkow, H.; Hyman, B.T.; Jack, C.R.; Kawas, C.H.; Klunk, W.E.; Koroshetz, W.J.; Manly, J.J.; Mayeux, R.; et al. The Diagnosis of Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association Workgroups on Diagnostic Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Andrews, J.S.; Beach, T.G.; Buracchio, T.; Dunn, B.; Graf, A.; Hansson, O.; Ho, C.; Jagust, W.; McDade, E.; et al. Revised Criteria for Diagnosis and Staging of Alzheimer’s Disease: Alzheimer’s Association Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 5143–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jack, C.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Blennow, K.; Carrillo, M.C.; Dunn, B.; Haeberlein, S.B.; Holtzman, D.M.; Jagust, W.; Jessen, F.; Karlawish, J.; et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a Biological Definition of Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porsteinsson, A.P.; Isaacson, R.S.; Knox, S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; Rubino, I. Diagnosis of Early Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Practice in 2021. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 8, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy, P.C.; McKeith, I.G. The Clinical Characteristics of Dementia with Lewy Bodies and a Consideration of Prodromal Diagnosis. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Komatsu, J.; Nakamura, K.; Sakai, K.; Samuraki-Yokohama, M.; Nakajima, K.; Yoshita, M. Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Updates and Future Directions. J. Mov. Dis. 2020, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Boeve, B.F.; Dickson, D.W.; Halliday, G.; Taylor, J.-P.; Weintraub, D.; Aarsland, D.; Galvin, J.; Attems, J.; Ballard, C.G.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Fourth Consensus Report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2017, 89, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, J.; Seo, W.; Hye, A.; Aarsland, D.; Hortobágyi, T. Dementia with Lewy Bodies—A Clinicopathological Update. Free Neuropathol. 2020, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beach, T.G.; Serrano, G.E.; Zhang, N.; Driver-Dunckley, E.D.; Sue, L.I.; Shill, H.A.; Mehta, S.H.; Belden, C.; Tremblay, C.; Choudhury, P.; et al. Clinicopathological Heterogeneity of Lewy Body Diseases: The Profound Influence of Comorbid Alzheimer’s Disease. medRxiv 2024. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeith, I.G.; Dickson, D.W.; Lowe, J.; Emre, M.; O’Brien, J.T.; Feldman, H.; Cummings, J.; Duda, J.E.; Lippa, C.; Perry, E.K.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Third Report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005, 65, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laczó, M.; Svacova, Z.; Lerch, O.; Martinkovic, L.; Krejci, M.; Nedelska, Z.; Horakova, H.; Matoska, V.; Vyhnalek, M.; Hort, J.; et al. Spatial Navigation Deficits in Early Alzheimer’s Disease: The Role of Biomarkers and APOE Genotype. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, R.; Wong, G.; Huang, X. Lewy Body Dementia: Exploring Biomarkers and Pathogenic Interactions of Amyloid β, Tau, and α-Synuclein. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rongve, A.; Soennesyn, H.; Skogseth, R.; Oesterhus, R.; Hortobágyi, T.; Ballard, C.; Auestad, B.H.; Aarsland, D. Cognitive Decline in Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A 5-Year Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.S.; Saeed, U.; Ramirez, J.; Herrmann, N.; Stuss, D.T.; Black, S.E.; Masellis, M. Effects of White Matter Hyperintensities, Neuropsychiatric Symptoms, and Cognition on Activities of Daily Living: Differences between Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 14, e12306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, L.K.; Lingler, J.; Lindauer, A. Alzheimer’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia: Discerning the Differences. Am. Nurse J. 2022, 16, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, L.L.; Skogseth, R.E.; Hortobagyi, T.; Vik-Mo, A.O.; Ballard, C.; Aarsland, D. Clinical Evolution of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia With Lewy Bodies in a Post-Mortem Cohort. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2025, 40, e70084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, D.P. Neuropathology of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mt. Sinai J. Med. 2010, 77, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, B.C.; Bakkour, A.; Salat, D.H.; Feczko, E.; Pacheco, J.; Greve, D.N.; Grodstein, F.; Wright, C.I.; Blacker, D.; Rosas, H.D.; et al. The Cortical Signature of Alzheimer’s Disease: Regionally Specific Cortical Thinning Relates to Symptom Severity in Very Mild to Mild AD Dementia and Is Detectable in Asymptomatic Amyloid-Positive Individuals. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arriagada, P.V.; Growdon, J.H.; Hedley-Whyte, E.T.; Hyman, B.T. Neurofibrillary Tangles but Not Senile Plaques Parallel Duration and Severiti of Azheimer’s Disease. Neurology 1992, 42 Pt 1, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, D.F.; Smirnov, D.S.; Coughlin, D.G.; Peng, I.; Standke, H.G.; Kim, Y.; Pizzo, D.P.; Unapanta, A.; Andreasson, T.; Hiniker, A.; et al. Early Alzheimer’s Disease with Frequent Neuritic Plaques Harbors Neocortical Tau Seeds Distinct from Primary Age-Related Tauopathy. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-Z.; Xia, Y.-Y.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Abnormal Hyperphosphorylation of Tau: Sites, Regulation, and Molecular Mechanism of Neurofibrillary Degeneration. J. Mov. Dis. 2012, 33, S123–S139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Braak, E. Neuropathological Stageing of Alzheimer-Related Changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991, 82, 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braak, H.; Alafuzoff, I.; Arzberger, T.; Kretzschmar, H.; Del Tredici, K. Staging of Alzheimer Disease-Associated Neurofibrillary Pathology Using Paraffin Sections and Immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006, 112, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-D.; Lu, J.-Y.; Li, H.-Q.; Yang, Y.-X.; Jiang, J.-H.; Cui, M.; Zuo, C.-T.; Tan, L.; Dong, Q.; Yu, J.-T.; et al. Staging Tau Pathology with Tau PET in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Longitudinal Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, D.R.; Rüb, U.; Orantes, M.; Braak, H. Phases of Aβ-Deposition in the Human Brain and Its Relevance for the Development of AD. Neurology 2002, 58, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montine, T.J.; Phelps, C.H.; Beach, T.G.; Bigio, E.H.; Cairns, N.J.; Dickson, D.W.; Duyckaerts, C.; Frosch, M.P.; Masliah, E.; Mirra, S.S.; et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer’s Association Guidelines for the Neuropathologic Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Practical Approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 123, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, J.; Szarka, M.; Bencs, V.; Szabó, R.N.; Smajda, M.; Aarsland, D.; Hortobágyi, T. Neuropathological Characterization of Lemur Tyrosine Kinase 2 (LMTK2) in Alzheimer’s Disease and Neocortical Lewy Body Disease. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelska, Z.; Ferman, T.J.; Boeve, B.F.; Przybelski, S.A.; Lesnick, T.G.; Murray, M.E.; Gunter, J.L.; Senjem, M.L.; Vemuri, P.; Smith, G.E.; et al. Pattern of Brain Atrophy Rates in Autopsy-Confirmed Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Neurobiol. Aging 2015, 36, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, L.; Fumagalli, G.G.; Barkhof, F.; Scheltens, P.; O’Brien, J.T.; Bouwman, F.; Burton, E.J.; Rohrer, J.D.; Fox, N.C.; Ridgway, G.R.; et al. MRI Visual Rating Scales in the Diagnosis of Dementia: Evaluation in 184 Post-Mortem Confirmed Cases. Brain 2016, 139, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attems, J.; Toledo, J.B.; Walker, L.; Gelpi, E.; Gentleman, S.; Halliday, G.; Hortobagyi, T.; Jellinger, K.; Kovacs, G.G.; Lee, E.B.; et al. Neuropathological Consensus Criteria for the Evaluation of Lewy Pathology in Post-Mortem Brains: A Multi-Centre Study. Acta Neuropathol. 2021, 141, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, T.; Uchihara, T.; Takahashi, A.; Nakamura, A.; Orimo, S.; Mizusawa, H. Three-Layered Structure Shared Between Lewy Bodies and Lewy Neurites—Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of Triple-Labeled Sections. Brain Pathol. 2008, 18, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, S.; Sekiya, H.; Kondru, N.; Ross, O.A.; Dickson, D.W. Neuropathology and Molecular Diagnosis of Synucleinopathies. Mol. Neurodegener. 2021, 16, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.; Holmes, C.; Dorey, R.B.; Tommasino, E.; Casal, Y.R.; Williams, D.M.; Dupuy, C.; Nicoll, J.A.R.; Boche, D. Neuroinflammation in Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Human Post-Mortem Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.J.; Karas, G.; Paling, S.M.; Barber, R.; Williams, E.D.; Ballard, C.G.; McKeith, I.G.; Scheltens, P.; Barkhof, F.; O’Brien, J.T. Patterns of Cerebral Atrophy in Dementia with Lewy Bodies Using Voxel-Based Morphometry. NeuroImage 2002, 17, 618–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.J.; Barber, R.; Mukaetova-Ladinska, E.B.; Robson, J.; Perry, R.H.; Jaros, E.; Kalaria, R.N.; O’Brien, J.T. Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy on MRI Differentiates Alzheimer’s Disease from Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Vascular Cognitive Impairment: A Prospective Study with Pathological Verification of Diagnosis. Brain 2009, 132, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, D.G.; Hurtig, H.I.; Irwin, D.J. Pathological Influences on Clinical Heterogeneity in Lewy Body Diseases. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skogseth, R.; Hortobágyi, T.; Soennesyn, H.; Chwiszczuk, L.; Ffytche, D.; Rongve, A.; Ballard, C.; Aarsland, D. Accuracy of Clinical Diagnosis of Dementia with Lewy Bodies versus Neuropathology. J. Mov. Dis. 2017, 59, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhr, S. Making Time for Brain Health: Recognising Temporal Inequity in Dementia Risk Reduction. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2025, 6, 100768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegambaram, M.; Manivannan, B.; Beach, T.; Halden, R. Role of Environmental Contaminants in the Etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review. Cur. Alzheimer Res. 2015, 12, 116–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin-Chan, M.; Navarro-Yepes, J.; Quintanilla-Vega, B. Environmental Pollutants as Risk Factors for Neurodegenerative Disorders: Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, V.V.; Masud, F.; Petronilho, F.; Dal-Pizzol, F.; Barichello, T. Infection-Induced Systemic Inflammation Is a Potential Driver of Alzheimer’s Disease Progression. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, R.E. The Genetics of Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellenguez, C.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Lambert, J.-C. Genetics of Alzheimer’s Disease: Where We Are, and Where We Are Going. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 61, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellenguez, C.; Küçükali, F.; Jansen, I.E.; Kleineidam, L.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Amin, N.; Naj, A.C.; Campos-Martin, R.; Grenier-Boley, B.; Andrade, V.; et al. New Insights into the Genetic Etiology of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias. Nat. Genet. 2022, 54, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korologou-Linden, R.; Bhatta, L.; Brumpton, B.M.; Howe, L.D.; Millard, L.A.C.; Kolaric, K.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Williams, D.M.; Smith, G.D.; Anderson, E.L.; et al. The Causes and Consequences of Alzheimer’s Disease: Phenome-Wide Evidence from Mendelian Randomization. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, S.; Bp, K.; C R, S.; Saikumar, N.V.; Philip, P.; Narayanan, M. Alzheimer’s Disease Rewires Gene Coexpression Networks Coupling Different Brain Regions. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2024, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamatham, P.T.; Shukla, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease: Breaking the Memory Barrier. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härtig, W.; Bauer, A.; Brauer, K.; Grosche, J.; Hortobágyi, T.; Penke, B.; Schliebs, R.; Harkany, T. Functional Recovery of Cholinergic Basal Forebrain Neurons under Disease Conditions: Old Problems, New Solutions? Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 13, 95–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Parkinson’s Disease-Dementia: Current Concepts and Controversies. J. Neural Transm. 2018, 125, 615–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agin, A.; Blanc, F.; Bousiges, O.; Villette, C.; Philippi, N.; Demuynck, C.; Martin-Hunyadi, C.; Cretin, B.; Lang, S.; Zumsteg, J.; et al. Environmental Exposure to Phthalates and Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Contribution of Metabolomics. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2020, 91, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-L.; Qu, Y.; Ou, Y.-N.; Zhang, Y.-R.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. Environmental Factors and Risks of Cognitive Impairment and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Wu, X.; Jia, L.; Gadhave, K.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, H.; Chen, R.; Kumbhar, R.; et al. Lewy Body Dementia Promotion by Air Pollutants. Science 2025, 389, eadu4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, R.; Sabir, M.S.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Saez-Atienzar, S.; Reynolds, R.H.; Gustavsson, E.; Walton, R.L.; Ahmed, S.; Viollet, C.; Ding, J.; et al. Genome Sequencing Analysis Identifies New Loci Associated with Lewy Body Dementia and Provides Insights into Its Genetic Architecture. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivola, K.; Shah, Z.; Chia, R.; International LBD Genomics Consortium; Black, S.E.; Gan-Or, Z.; Keith, J.; Masellis, M.; Rogaeva, E.; Brice, A.; et al. Genetic Evaluation of Dementia with Lewy Bodies Implicates Distinct Disease Subgroups. Brain 2022, 145, 1757–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalls, M.A.; Blauwendraat, C.; Vallerga, C.L.; Heilbron, K.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Chang, D.; Tan, M.; Kia, D.A.; Noyce, A.J.; Xue, A.; et al. Identification of Novel Risk Loci, Causal Insights, and Heritable Risk for Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talyansky, S.; Le Guen, Y.; Kasireddy, N.; Belloy, M.E.; Greicius, M.D. APOE-Ε4 and BIN1 Increase Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology but Not Specifically of Lewy Body Pathology. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2023, 11, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, R.; Ross, O.A.; Kun-Rodrigues, C.; Hernandez, D.G.; Orme, T.; Eicher, J.D.; Shepherd, C.E.; Parkkinen, L.; Darwent, L.; Heckman, M.G.; et al. Investigating the Genetic Architecture of Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Two-Stage Genome-Wide Association Study. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.A.; Higgins, G.A. Alzheimer’s Disease: The Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis. Science 1992, 256, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkoe, D.J.; Hardy, J. The Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease at 25 Years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016, 8, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-Q.; Mobley, W.C. Exploring the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer Disease in Basal Forebrain Cholinergic Neurons: Converging Insights From Alternative Hypotheses. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Luehmann, M.; Spires-Jones, T.L.; Prada, C.; Garcia-Alloza, M.; De Calignon, A.; Rozkalne, A.; Koenigsknecht-Talboo, J.; Holtzman, D.M.; Bacskai, B.J.; Hyman, B.T. Rapid Appearance and Local Toxicity of Amyloid-β Plaques in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2008, 451, 720–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, N.; Cheung, T.T.; Cai, X.-D.; Odaka, A.; Otvos, L.; Eckman, C.; Golde, T.E.; Younkin, S.G. An Increased Percentage of Long Amyloid β Protein Secreted by Familial Amyloid β Protein Precursor (βApp717) Mutants. Science 1994, 264, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P.; LeVine, H. Alzheimer’s Disease and the Amyloid-β Peptide. J. Mov. Dis. 2010, 19, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, P.T.; Palmer, A.M.; Snape, M.; Wilcock, G.K. The Cholinergic Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of Progress. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1999, 66, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.-M.; Cuello, A.C.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Farlow, M.R.; Snyder, P.J.; Giacobini, E.; Khachaturian, Z.S. Revisiting the Cholinergic Hypothesis in Alzheimer’s Disease: Emerging Evidence from Translational and Clinical Research. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 6, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila, J.; Lucas, J.J.; Pérez, M.; Hernández, F. Role of Tau Protein in Both Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.C.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K. Alzheimer’s Disease Hyperphosphorylated Tau Sequesters Normal Tau into Tangles of Filaments and Disassembles Microtubules. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 783–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moloney, C.M.; Lowe, V.J.; Murray, M.E. Visualization of Neurofibrillary Tangle Maturity in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Clinicopathologic Perspective for Biomarker Research. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1554–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguzzi, A.; Lakkaraju, A.K.K. Cell Biology of Prions and Prionoids: A Status Report. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, B.; Stancu, I.-C.; Buist, A.; Bird, M.; Wang, P.; Vanoosthuyse, A.; Van Kolen, K.; Verheyen, A.; Kienlen-Campard, P.; Octave, J.-N.; et al. Heterotypic Seeding of Tau Fibrillization by Pre-Aggregated Abeta Provides Potent Seeds for Prion-like Seeding and Propagation of Tau-Pathology in Vivo. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-β and Tau: The Trigger and Bullet in Alzheimer Disease Pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAleese, K.E.; Walker, L.; Erskine, D.; Thomas, A.J.; McKeith, I.G.; Attems, J. TDP-43 Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Ageing. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.; Soga, T.; Okano, H.J.; Parhar, I. α-Synuclein-Mediated Neurodegeneration in Dementia with Lewy Bodies: The Pathobiology of a Paradox. Cell Biosci. 2021, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupane, S.; De Cecco, E.; Aguzzi, A. The Hidden Cell-to-Cell Trail of α-Synuclein Aggregates. J. Mol. Biol. 2022, 167930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.I.; Lee, J.; Monteiro, O.; Woerman, A.L.; Lazar, A.A.; Condello, C.; Paras, N.A.; Prusiner, S.B. Different α-Synuclein Prion Strains Cause Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Multiple System Atrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2113489119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdiuk, T.; Redeker, V.; Savistchenko, J.; Neupane, S.; Haenseler, W.; Fleischmann, Y.; Reber, V.; Keller, S.; Tiberi, C.; Bachmann-Gagescu, R.; et al. Structure-Function Relationship of Alpha-Synuclein Fibrillar Polymorphs Derived from Distinct Synucleinopathies. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Perren, A.; Gelders, G.; Fenyi, A.; Bousset, L.; Brito, F.; Peelaerts, W.; Van Den Haute, C.; Gentleman, S.; Melki, R.; Baekelandt, V. The Structural Differences between Patient-Derived α-Synuclein Strains Dictate Characteristics of Parkinson’s Disease, Multiple System Atrophy and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2020, 139, 977–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.L.; Covell, D.J.; Daniels, J.P.; Iba, M.; Stieber, A.; Zhang, B.; Riddle, D.M.; Kwong, L.K.; Xu, Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Distinct α-Synuclein Strains Differentially Promote Tau Inclusions in Neurons. Cell 2013, 154, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassil, F.; Brown, H.J.; Pattabhiraman, S.; Iwasyk, J.E.; Maghames, C.M.; Meymand, E.S.; Cox, T.O.; Riddle, D.M.; Zhang, B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Amyloid-Beta (Aβ) Plaques Promote Seeding and Spreading of Alpha-Synuclein and Tau in a Mouse Model of Lewy Body Disorders with Aβ Pathology. Neuron 2020, 105, 260–275.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zempel, H.; Thies, E.; Mandelkow, E.; Mandelkow, E.-M. Aβ Oligomers Cause Localized Ca2+ Elevation, Missorting of Endogenous Tau into Dendrites, Tau Phosphorylation, and Destruction of Microtubules and Spines. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 11938–11950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giasson, B.I.; Forman, M.S.; Higuchi, M.; Golbe, L.I.; Graves, C.L.; Kotzbauer, P.T.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Lee, V.M.-Y. Initiation and Synergistic Fibrillization of Tau and Alpha-Synuclein. Science 2003, 300, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Sorrentino, Z.; Weinrich, M.; Giasson, B.I.; Chakrabarty, P. Differential Cross-Seeding Properties of Tau and α-Synuclein in Mouse Models of Tauopathy and Synucleinopathy. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, L.K.; Blurton-Jones, M.; Myczek, K.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; LaFerla, F.M. Synergistic Interactions between Aβ, Tau, and α-Synuclein: Acceleration of Neuropathology and Cognitive Decline. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 7281–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kukreti, R.; Saso, L.; Kukreti, S. Oxidative Stress: A Key Modulator in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuner, K.; Schütt, T.; Kurz, C.; Eckert, S.H.; Schiller, C.; Occhipinti, A.; Mai, S.; Jendrach, M.; Eckert, G.P.; Kruse, S.E.; et al. Mitochondrion-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species Lead to Enhanced Amyloid Beta Formation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swerdlow, R.H. The Alzheimer’s Disease Mitochondrial Cascade Hypothesis: A Current Overview. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 92, 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.J.; Sagara, Y.; Arroyo, A.; Rockenstein, E.; Sisk, A.; Mallory, M.; Wong, J.; Takenouchi, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Masliah, E. α-Synuclein Promotes Mitochondrial Deficit and Oxidative Stress. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billingsley, K.J.; Barbosa, I.A.; Bandrés-Ciga, S.; Quinn, J.P.; Bubb, V.J.; Deshpande, C.; Botia, J.A.; Reynolds, R.H.; Zhang, D.; Simpson, M.A.; et al. Mitochondria Function Associated Genes Contribute to Parkinson’s Disease Risk and Later Age at Onset. npj Park. Dis. 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spano, M. The Possible Involvement of Mitochondrial Dysfunctions in Lewy Body Dementia: A Systematic Review. Funct. Neurol. 2015, 30, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Dai, X.; Zhang, C.; Duan, Z.; Zhou, G.; Wang, J. Investigating the Causal Relationships between Mitochondrial Proteins and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, 105, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millot, P.; Pujol, C.; Paquet, C.; Mouton-Liger, F. Impaired Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Blood of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, e075795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; Khoury, J.E.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-Y.; Tan, M.-S.; Yu, J.-T.; Tan, L. Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Released from Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 2015, 3, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Griciuc, A.; Patel, S.; Federico, A.N.; Choi, S.H.; Innes, B.J.; Oram, M.K.; Cereghetti, G.; McGinty, D.; Anselmo, A.; Sadreyev, R.I.; et al. TREM2 Acts Downstream of CD33 in Modulating Microglial Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 103, 820–835.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Van Der Flier, W.M.; Jessen, F.; Hoozemanns, J.; Thal, D.R.; Boche, D.; Brosseron, F.; Teunissen, C.; Zetterberg, H.; Jacobs, A.H.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2025, 25, 321–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantone, D.; Pardini, M.; Righi, D.; Manco, C.; Colombo, B.M.; De Stefano, N. The Role of TNF-α in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Cells 2023, 13, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, T.J.; Murray, T.E.; Noyovitz, B.; Narayana, K.; Gray, T.E.; Le, J.; He, J.; Simtchouk, S.; Gibon, J.; Alcorn, J.; et al. Cardiolipin Released by Microglia Can Act on Neighboring Glial Cells to Facilitate the Uptake of Amyloid-β (1–42). Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 124, 103804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A.; Attems, J. Prevalence and Impact of Vascular and Alzheimer Pathologies in Lewy Body Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2008, 115, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellinger, K.A. Alzheimer Disease and Cerebrovascular Pathology: An Update. J. Neural Transm. 2002, 109, 813–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attems, J.; Jellinger, K.A. Only Cerebral Capillary Amyloid Angiopathy Correlates with Alzheimer Pathology? A Pilot Study. Acta Neuropathol. 2004, 107, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, V.; Fann, D.Y.; Dinh, Q.N.; Kim, H.A.; De Silva, T.M.; Lai, M.K.P.; Chen, C.L.-H.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; Arumugam, T.V. Pathophysiology of Blood Brain Barrier Dysfunction during Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion in Vascular Cognitive Impairment. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenaro, E.; Piacentino, G.; Constantin, G. The Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2017, 107, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Magnus, T. Neuroinflammation, Stroke, Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction, and Imaging Modalities. Stroke 2022, 53, 1473–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, T.Y.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, X. Peripheral and Central Neuroimmune Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cechetto, D.F.; Hachinski, V.; Whitehead, S.N. Vascular Risk Factors and Alzheimer’s Disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2008, 8, 743–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendranathan, A.; Rowe, J.B.; O’Brien, J.T. Neuroinflammation in Lewy Body Dementia. Park. Relat. Disord. 2015, 21, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, A.P.; Bidkhori, G.; Shoaie, S.; Clarke, E.; Morrin, H.; Hye, A.; Williams, G.; Ballard, C.; Francis, P.; Aarsland, D. Postmortem Cortical Transcriptomics of Lewy Body Dementia Reveal Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Lack of Neuroinflammation. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2020, 28, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellinger, K.A. Prevalence of Vascular Lesions in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. A Postmortem Study. J. Neural Transm. 2003, 110, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.C.B.; Carter, E.K.; Dammer, E.B.; Duong, D.M.; Gerasimov, E.S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Betarbet, R.; Ping, L.; Yin, L.; et al. Large-Scale Deep Multi-Layer Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Reveals Strong Proteomic Disease-Related Changes Not Observed at the RNA Level. Nat. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, H.; Davila-Velderrain, J.; Peng, Z.; Gao, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Young, J.Z.; Menon, M.; He, L.; Abdurrob, F.; Jiang, X.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2019, 570, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knörnschild, F.; Zhang, E.J.; Ghosh Biswas, R.; Kobus, M.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.X.; Rao, A.; Sun, J.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; et al. Correlations of Blood and Brain NMR Metabolomics with Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, T.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Tsuneyoshi, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Aoshima, K.; Tsugawa, H.; The Alzheimer’s Disease Metabolomics Consortium; Weiner, M.; Aisen, P.; Petersen, R.; et al. Multiomics Analysis to Explore Blood Metabolite Biomarkers in an Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Cohort. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greally, S.; Kumar, M.; Schlaffner, C.; Van Der Heijden, H.; Lawton, E.S.; Biswas, D.; Berretta, S.; Steen, H.; Steen, J.A. Dementia with Lewy Bodies Patients with High Tau Levels Display Unique Proteome Profiles. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goralski, T.M.; Meyerdirk, L.; Breton, L.; Brasseur, L.; Kurgat, K.; DeWeerd, D.; Turner, L.; Becker, K.; Adams, M.; Newhouse, D.J.; et al. Spatial Transcriptomics Reveals Molecular Dysfunction Associated with Cortical Lewy Pathology. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Donaghy, P.C.; Roberts, G.; Chouliaras, L.; O’Brien, J.T.; Thomas, A.J.; Heslegrave, A.J.; Zetterberg, H.; McGuinness, B.; Passmore, A.P.; et al. Plasma Metabolites Distinguish Dementia with Lewy Bodies from Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cross-Sectional Metabolomic Analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1326780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canal-Garcia, A.; Branca, R.M.; Francis, P.T.; Ballard, C.; Winblad, B.; Lehtiö, J.; Nilsson, P.; Aarsland, D.; Pereira, J.B.; Bereczki, E. Proteomic Signatures of Alzheimer’s Disease and Lewy Body Dementias: A Comparative Analysis. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantaraman, A.; Dammer, E.B.; Ugochukwu, O.; Duong, D.M.; Yin, L.; Carter, E.K.; Gearing, M.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; Lee, E.B.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; et al. Network Proteomics of the Lewy Body Dementia Brain Reveals Presynaptic Signatures Distinct from Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habbal, S.; Mian, M.; Imam, M.; Tahiri, J.; Amor, A.; Reddy, P.H. Harnessing Artificial Intelligence for Transforming Dementia Care: Innovations in Early Detection and Treatment. Brain Organoid Syst. Neurosci. J. 2025, 3, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, T.R.; Brookes, K.J.; Sharma, R.; Moemeni, A.; Rajkumar, A.P. Dementia with Lewy Bodies: Genomics, Transcriptomics, and Its Future with Data Science. Cells 2024, 13, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, P.; Guo, Y.; Yu, J. Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease: Emerging Trends and Clinical Implications. Chin. Med. J. 2025, 138, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jellinger, K.A. Criteria for the Neuropathological Diagnosis of Dementing Disorders: Routes out of the Swamp? Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 117, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGettigan, S.; Nolan, Y.; Ghosh, S.; O’Mahony, D. The Emerging Role of Blood Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, G.; Valletta, M.; Rizzuto, D.; Xia, X.; Qiu, C.; Orsini, N.; Dale, M.; Andersson, S.; Fredolini, C.; Winblad, B.; et al. Blood-Based Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease and Incident Dementia in the Community. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2027–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, M.R.; Upadhyaya, P.G.; Hashim, A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Chanu, N.R.; Das, D.; Khanal, P.; Deka, S. Advanced Biomarkers: Beyond Amyloid and Tau: Emerging Non-Traditional Biomarkers for Alzheimer`s Diagnosis and Progression. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 108, 102736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polykretis, P.; Bessi, V.; Banchelli, M.; De Angelis, M.; Cecchi, C.; Nacmias, B.; Chiti, F.; D’Andrea, C.; Matteini, P. Fibrillar Structures Detected by AFM in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients Affected by Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurological Conditions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2025, 770, 110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutrot, A.; Schmidt, S.; Coutrot, L.; Pittman, J.; Hong, L.; Wiener, J.M.; Hölscher, C.; Dalton, R.C.; Hornberger, M.; Spiers, H.J. Virtual Navigation Tested on a Mobile App Is Predictive of Real-World Wayfinding Navigation Performance. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.; Bouter, C.; Müller, S.J.; Van Riesen, C.; Khadhraoui, E.; Ernst, M.; Riedel, C.H.; Wiltfang, J.; Lange, C. New Insights into Potential Biomarkers in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment Occurring in the Prodromal Stage of Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, S.K. Updates in Fluid, Tissue, and Imaging Biomarkers for Dementia with Lewy Bodies and Implications for Biologically Based Disease Definitions. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2024, 26, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Surmeier, D.J.; Simuni, T.; Merchant, K.; Caughey, B.; Soto, C.; Fares, M.-B.; Heym, R.G.; Melki, R. Alpha-Synuclein Seed Amplification Assays: Data Sharing, Standardization Needed for Clinical Use. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt7195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bsoul, R.; McWilliam, O.H.; Waldemar, G.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Simonsen, A.H.; Von Buchwald, C.; Bech, M.; Pinborg, C.H.; Pedersen, C.K.; Baungaard, S.O.; et al. Accurate Detection of Pathologic α-Synuclein in CSF, Skin, Olfactory Mucosa, and Urine with a Uniform Seeding Amplification Assay. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjaelland, N.S.; Gramkow, M.H.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Frederiksen, K.S. Digital Biomarkers for the Assessment of Non-Cognitive Symptoms in Patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies: A Systematic Review. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 100, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Campo, M.; Vermunt, L.; Peeters, C.F.W.; Sieben, A.; Hok-A-Hin, Y.S.; Lleó, A.; Alcolea, D.; Van Nee, M.; Engelborghs, S.; Van Alphen, J.L.; et al. CSF Proteome Profiling Reveals Biomarkers to Discriminate Dementia with Lewy Bodies from Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Comorbid Pathologies and Their Impact on Dementia with Lewy Bodies—Current View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuello, C.; Lim, K.; Nisini, G.; Pokrovsky, V.S.; Conde, J.; Ruggeri, F.S. Nanoscale Analysis beyond Imaging by Atomic Force Microscopy: Molecular Perspectives on Oncology and Neurodegeneration. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2500351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J.; Chiao, P.; Bussière, T.; Weinreb, P.H.; Williams, L.; Maier, M.; Dunstan, R.; Salloway, S.; Chen, T.; Ling, Y.; et al. The Antibody Aducanumab Reduces Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2016, 537, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Nikolić, L.; Maraio, L.; Goiran, T.; Karpilovsky, N.; Sellitto, S.; Bouris, V.; Yin, J.-A.; Melki, R.; Fon, E.A.; et al. Large-Scale Bidirectional Arrayed Genetic Screens Identify OXR1 and EMC4 as Modifiers of α-Synuclein Aggregation. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Khadka, J.; Rayamajhi, S.; Pandey, A.S. Binding Modes of Potential Anti-Prion Phytochemicals to PrPC Structures in Silico. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2023, 14, 100750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacesa, M.; Nickel, L.; Schellhaas, C.; Schmidt, J.; Pyatova, E.; Kissling, L.; Barendse, P.; Choudhury, J.; Kapoor, S.; Alcaraz-Serna, A.; et al. One-Shot Design of Functional Protein Binders with BindCraft. Nature 2025, 646, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neupane, S.; Hortobágyi, T. Molecular Crossroads: Shared and Divergent Molecular Signatures in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411811

Neupane S, Hortobágyi T. Molecular Crossroads: Shared and Divergent Molecular Signatures in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411811

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeupane, Sandesh, and Tibor Hortobágyi. 2025. "Molecular Crossroads: Shared and Divergent Molecular Signatures in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411811

APA StyleNeupane, S., & Hortobágyi, T. (2025). Molecular Crossroads: Shared and Divergent Molecular Signatures in Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11811. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411811