Disease-Free Survival of Patients with Stage II Stroma-Rich Colorectal Adenocarcinomas with Microsatellite Stability

Abstract

1. Introduction

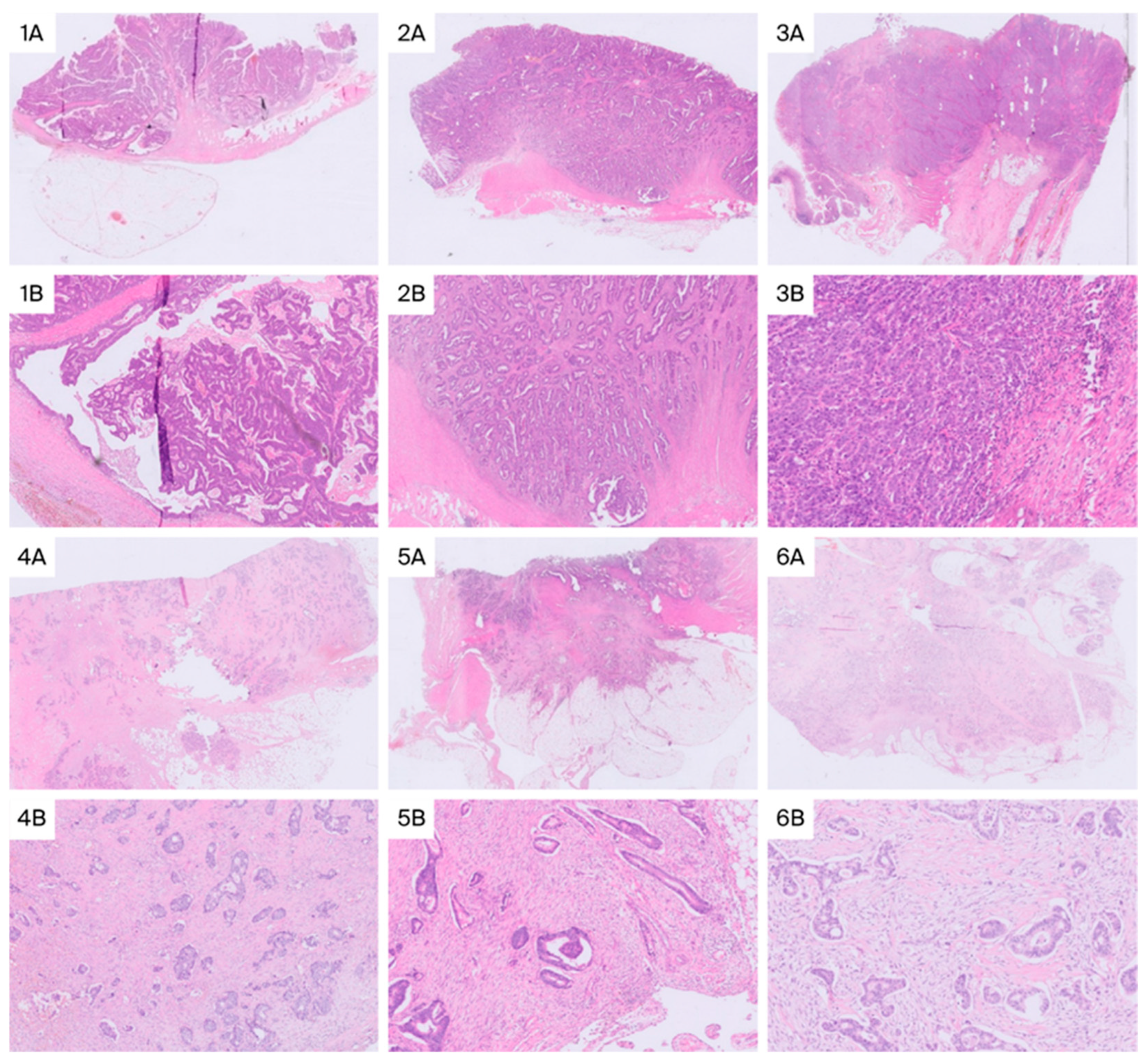

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical Considerations

4.2. Patient Selection

4.3. Study Variables

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Sierra, M.S.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut 2017, 66, 683–691. [Google Scholar]

- Saez De Gordoa, K.; Rodrigo-Calvo, M.T.; Archilla, I.; Lopez-Prades, S.; Diaz, A.; Tarragona, J.; Machado, I.; Martín, J.R.; Zaffalon, D.; Daca-Alvarez, M.; et al. Lymph Node Molecular Analysis with OSNA Enables the Identification of pT1 CRC Patients at Risk of Recurrence: A Multicentre Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 5481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Mercedes, S.; Archilla, I.; Camps, J.; De Lacy, A.; Gorostiaga, I.; Momblan, D.; Ibarzabal, A.; Maurel, J.; Chic, N.; Bombí, J.A.; et al. Budget Impact Analysis of Molecular Lymph Node Staging Versus Conventional Histopathology Staging in Colorectal Carcinoma. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2019, 17, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, G.; Chang, X. Revisiting the survival paradox between stage IIB/C and IIIA colon cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghi, L.; Negri, F.; Gaiani, F.; Cavalleri, T.; Grizzi, F.; Luigi De’ Angelis, G.; Malesci, A. Prognostic and Predictive Cross-Roads of Microsatellite Instability and Immune Response to Colon Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polack, M.; Smit, M.A.; Van Pelt, G.W.; Roodvoets, A.G.H.; Meershoek-Klein Kranenbarg, E.; Putter, H.; Gelderblom, H.; Crobach, A.S.L.P.; Terpstra, V.; Petrushevska, G.; et al. Results from the UNITED study: A multicenter study validating the prognostic effect of the tumor-stroma ratio in colon cancer. ESMO Open 2024, 9, 102988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Union for International Cancer Control. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours, 9th ed.; Brierley, J., Giuliani, M., O’Sullivan, B., Rous, B., Van Eycken, E., Eds.; Union for International Cancer Control: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guinney, J.; Dienstmann, R.; Wang, X.; De Reyniès, A.; Schlicker, A.; Soneson, C.; Marisa, L.; Roepman, P.; Nyamundanda, G.; Angelino, P.; et al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calon, A.; Lonardo, E.; Berenguer-Llergo, A.; Espinet, E.; Hernando-Momblona, X.; Iglesias, M.; Sevillano, M.; Palomo-Ponce, S.; Tauriello, D.V.F.; Byrom, D.; et al. Stromal gene expression defines poor-prognosis subtypes in colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. TGFβ signalling in context. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, M.; Evans, S.R.; Vidal-Vanaclocha, F.; Calvo, A. Role of TGF-β in metastatic colon cancer: It is finally time for targeted therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 370, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurzu, S.; Silveanu, C.; Fetyko, A.; Butiurca, V.; Kovacs, Z.; Jung, I. Systematic review of the old and new concepts in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 6764–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhpazyan, N.; Mikhaleva, L.; Bedzhanyan, A.; Gioeva, Z.; Sadykhov, N.; Mikhalev, A.; Atiakshin, D.; Buchwalow, I.; Tiemann, M.; Orekhov, A. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of the Tumor Stroma in Colorectal Cancer: Insights into Disease Progression and Therapeutic Targets. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridman, W.H.; Miller, I.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Byrne, A.T. Therapeutic Targeting of the Colorectal Tumor Stroma. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukaida, N.; Sasaki, S. Fibroblasts, an inconspicuous but essential player in colon cancer development and progression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 5301–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, J.; Thomas, G. The role of tumour stroma in colorectal cancer invasion and metastasis. Cancers 2011, 3, 2160–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraman, M.; Bambrough, P.J.; Arnold, J.N.; Roberts, E.W.; Magiera, L.; Jones, J.O.; Gopinathan, A.; Tuveson, D.A.; Fearon, D.T. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-α. Science 2010, 330, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, M.; Novitskiy, S.; Moses, H.L. The roles of TGFβ in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takigawa, H.; Kitadai, Y.; Shinagawa, K.; Yuge, R.; Higashi, Y.; Tanaka, S.; Yasui, W.; Chayama, K. Multikinase inhibitor regorafenib inhibits the growth and metastasis of colon cancer with abundant stroma. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeldag, G.; Rice, A.; Del Río Hernández, A. Chemoresistance and the Self-Maintaining Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2018, 10, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strous, M.T.A.; Faes, T.K.E.; Gubbels, A.L.H.M.; van der Linden, R.L.A.; Mesker, W.E.; Bosscha, K.; Bronkhorst, C.M.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Vogelaar, F.J.; de Bruïne, A.P. A high tumour-stroma ratio (TSR) in colon tumours and its metastatic lymph nodes predicts poor cancer-free survival and chemo resistance. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Pelt, G.W.; Kjaer-Frifeldt, S.; Van Krieken, J.H.J.M.; Al Dieri, R.; Morreau, H.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Sørensen, F.B.; Mesker, W.E. Scoring the tumor-stroma ratio in colon cancer: Procedure and recommendations. Virchows Arch. 2018, 473, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomar de Lucas, B.; Heras, B.; Tarazona, N.; Ortega, M.; Huerta, M.; Moro, D.; Roselló, S.; Roda, D.; Pla, V.; Cervantes, A.; et al. Extended tumor area-based stratification score combining tumor budding and stroma identifies a high-risk, immune-depleted group in localized microsatellite-stable colon cancer patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2025, 269, 155871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Li, G.M. DNA mismatch repair in cancer immunotherapy. NAR Cancer 2023, 5, zcad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, D.T.; Uram, J.N.; Wang, H.; Bartlett, B.R.; Kemberling, H.; Eyring, A.D.; Skora, A.D.; Luber, B.S.; Azad, N.S.; Laheru, D.; et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2509–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.P.; Dattani, M.; Mcshane, P.; Hutchins, G.; Grabsch, J.; Mueller, W.; Treanor, D.; Quirke, P.; Grabsch, H. The proportion of tumour cells is an independent predictor for survival in colorectal cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 102, 1519–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, T.; Hashimoto, I.; Oshima, T. The Clinical Impact of the Tumor Stroma Ratio in Gastrointestinal Cancer Treatment. Anticancer Res. 2023, 43, 1877–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheer, R.; Baidoshvili, A.; Zoidze, S.; Elferink, M.A.G.; Berkel, A.E.M.; Klaase, J.M.; van Diest, P.J. Tumor-stroma ratio as prognostic factor for survival in rectal adenocarcinoma: A retrospective cohort study. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017, 9, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, Z.; Yao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Xu, Z.; Wu, L.; Huang, Y.; Liang, C.; Liu, Z. Artificial intelligence quantified tumour-stroma ratio is an independent predictor for overall survival in resectable colorectal cancer. EBioMedicine 2020, 61, 103054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, M.D.; Pickard, K.; Mitter, R.; Sayan, A.E.; Primrose, J.N.; Ivan, C.; Calin, G.A.; Thomas, G.J.; Packham, G.K.; Mirnezami, A.H. Stratifying risk of recurrence in stage II colorectal cancer using deregulated stromal and epithelial microRNAs. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7262–7279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B.S.; Jørgensen, S.; Fog, J.U.; Søkilde, R.; Christensen, I.J.; Hansen, U.; Brünner, N.; Baker, A.; Møller, S.; Nielsen, H.J. High levels of microRNA-21 in the stroma of colorectal cancers predict short disease-free survival in stage II colon cancer patients. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2011, 28, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, A.C.; Sørensen, F.B.; Lindebjerg, J.; Hager, H.; dePont Christensen, R.; Kjær-Frifeldt, S.; Hansen, T.F. The prognostic value of tumour stroma ratio and tumour budding in stage II colon cancer. A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2018, 33, 1115–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengin, M. Tumour Budding and Tumour Stroma Ratio are Reliable Predictors for Death and Recurrence in Elderly Stage I Colon Cancer Patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, M.A.; van Pelt, G.W.; Terpstra, V.; Putter, H.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Mesker, W.E.; van Krieken, J.H.J.M. Tumour-stroma ratio outperforms tumour budding as biomarker in colon cancer: A cohort study. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2729–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, M.; Benek, S. The Proportion of Tumour-Stroma in Metastatic Lymph Nodes is An Accurately Prognostic Indicator of Poor Survival for Advanced-Stage Colon Cancers. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2020, 26, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, L.; Pacheco, R.R.; Kmeid, M.; Chen, A.; Lee, H. Tumor Stroma Ratio and Its Significance in Locally Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 3232–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huijbers, A.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; VPelt, G.W.; Zeestraten, E.C.M.; Dutton, S.; Mcconkey, C.C.; Domingo, E.; Smit, V.T.H.B.M.; Midgley, R.; Warren, B.F.; et al. The proportion of tumor-stroma as a strong prognosticator for stage II and III colon cancer patients: Validation in the VICTOR trial. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 24, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Richards, C.H.; McMillan, D.C.; Horgan, P.G.; Roxburgh, C.S.D. The relationship between tumour stroma percentage, the tumour microenvironment and survival in patients with primary operable colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunder, S.M.; Van Pelt, G.W.; Gelderblom, H.J.; Mancao, C.; Putter, H.; Tollenaar, R.A.; Mesker, W.E. Predictive potential of tumour-stroma ratio on benefit from adjuvant bevacizumab in high-risk stage II and stage III colon cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, T.P.; Oosting, J.; Van Pelt, G.W.; Mesker, W.E.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Morreau, H. Molecular profiling of colorectal tumors stratified by the histological tumor-stroma ratio-Increased expression of galectin-1 in tumors with high stromal content. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 31502–31515, Erratum in Oncotarget 2019, 10, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Yang, L.; Xu, S.; Tan, L.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, T.; Zhou, L.; Feng, L.; Lian, S.; et al. Exploring prognostic values of DNA ploidy, stroma-tumor fraction and nucleotyping in stage II colon cancer patients. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, M.P.; Korsgaard, U.; Timm, S.; Hansen, T.F.; Zlobec, I.; Hager, H.; Kjær-Frifeldt, S. Prognostic Value of Tumor-Stroma Ratio in a Screened Stage II Colon Cancer Population: Intratumoral Site-Specific Assessment and Tumor Budding Synergy. Mod. Pathol. 2025, 38, 100738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strous, M.T.A.; van der Linden, R.L.A.; Gubbels, A.L.H.M.; Faes, T.K.E.; Bosscha, K.; Bronkhorst, C.M.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; de Bruïne, A.P.; Vogelaar, F.J. Node-negative colon cancer: Histological, molecular, and stromal features predicting disease recurrence. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T.; Sameshima, S.; Takeshita, E.; Mitsui, T.; Noro, T.; Ono, Y.; Noie, T.; Ban, S.; Oya, M. Myxoid stroma is associated with postoperative relapse in patients with stage II colon cancer. BMC Cancer 2020, 20, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, H.; van Pelt, G.W.; Haasnoot, K.J.C.; Backes, Y.; Elias, S.G.; Seerden, T.C.J.; Schwartz, M.P.; Spanier, B.W.M.; Cappel, W.H.d.V.T.N.; van Bergeijk, J.D.; et al. Tumour-stroma ratio has poor prognostic value in nonpedunculated T1 colorectal cancer: A multicentre case-cohort study. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 9, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, Z.; Ignat, P.; Resiga, A.C.; Todor, N.; Muntean, A.S.; Resiga, L.; Curcean, S.; Lazar, G.; Gherman, A.; Eniu, D. Unselective Measurement of Tumor-to-Stroma Proportion in Colon Cancer at the Invasion Front—An Elusive Prognostic Factor: Original Patient Data and Review of the Literature. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Banner, B.M.; Schäfer, E.M.; Mayr, P.; Anthuber, M.; Schenkirsch, G.; Märkl, B. Tumor proportion in colon cancer: Results from a semiautomatic image analysis approach. Virchows Arch. 2020, 477, 185–193, Erratum in Virchows Arch. 2021, 478, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.; Grosser, B.; Kempkens, L.; Miller, S.; Bauer, S.; Dhillon, C.; Banner, B.M.; Brendel, E.-M.; Sipos, É.; Vlasenko, D.; et al. Stroma areactive invasion front areas (SARIFA)—A new easily to determine biomarker in colon cancer—Results of a retrospective study. Cancers 2021, 13, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsam, N.G.; Grosser, B.; Enke, J.S.; Mueller, W.; Westwood, A.; West, N.P.; Quirke, P.; Märkl, B.; Grabsch, H. Stroma AReactive Invasion Front Areas (SARIFA): A novel histopathologic biomarker in colorectal cancer patients and its association with the luminal tumour proportion. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 44, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, H.; Enomoto, A.; Woods, S.L.; Burt, A.D.; Takahashi, M.; Worthley, D.L. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastrointestinal cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Torphy, R.J.; Steiger, K.; Hongo, H.; Ritchie, A.J.; Kriegsmann, M.; Horst, D.; Umetsu, S.E.; Joseph, N.M.; McGregor, K.; et al. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression is restrained by stromal matrix. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4704–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, B.C.; Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Carstens, J.L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, C.C.; Simpson, T.R.; Laklai, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Kahlert, C.; Novitskiy, S.V.; et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, A.D.; Oberstein, P.E.; Thomas, D.H.; Mirek, E.T.; Palermo, C.F.; Sastra, S.A.; Dekleva, E.N.; Saunders, T.; Becerra, C.P.; Tattersall, I.W.; et al. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza da Silva, R.M.; Queiroga, E.M.; Paz, A.R.; Neves, F.F.P.; Cunha, K.S.; Dias, E.P. Standardized Assessment of the Tumor-Stroma Ratio in Colorectal Cancer: Interobserver Validation and Reproducibility of a Potential Prognostic Factor. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 14, 2632010X21989686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Pelt, G.W.; Sandberg, T.P.; Morreau, H.; Gelderblom, H.; van Krieken, J.H.J.M.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Mesker, W.E. The tumour-stroma ratio in colon cancer: The biological role and its prognostic impact. Histopathology 2018, 73, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, A.; van Pelt, G.W.; Kerr, R.S.; Johnstone, E.C.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M.; Kerr, D.J.; Mesker, W.E. The value of additional bevacizumab in patients with high-risk stroma-high colon cancer. A study within the QUASAR2 trial, an open-label randomized phase 3 trial. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B.L.; Park, I.J.; Ro, J.S.; Kim, Y.I.; Lim, S.B.; Yu, C.S. Oncologic outcomes and associated factors of colon cancer patients aged 70 years and older. Ann. Coloproctol. 2025, 41, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Low Stroma (n, %) | High Stroma (n, %) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (n = 131) | 115 (87.8) | 16 (12.2) | - |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 37 (32.2) | 5 (31.2) | 0.941 |

| Male | 78 (67.8) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Age | |||

| ≤70 Years | 42 (36.5) | 3 (18.7) | 0.260 * |

| >70 Years | 73 (63.5) | 13 (81.3) | |

| Tumor Location | |||

| Right Colon | 34 (29.6) | 5 (31.2) | 0.890 |

| Left Colon–Rectum | 81 (70.4) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Histology | |||

| NOS | 100 (87) | 14 (87.5) | 1.000 * |

| Others | 15 (13) | 2 (12.5) | |

| pT Stage | |||

| pT3 | 36 (31.3) | 6 (37.5) | 0.619 |

| pT4 (pT4a–pT4b) | 79 (68.7) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Lymphatic Invasion | |||

| Absent | 110 (95.7) | 15 (93.8) | 0.550 * |

| Present | 5 (4.3) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Vascular Invasion | |||

| Absent | 89 (77.4) | 12 (75) | 0.761 * |

| Present | 26 (22.6) | 4 (25) | |

| Perineural Invasion | |||

| Absent | 103 (89.6) | 15 (93.8) | 1.000 * |

| Present | 12 (10.4) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Tumor Budding | |||

| Low–Intermediate (0–9) | 114 (99.1) | 13 (81.3) | 0.006 * |

| High (≥10) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (18.7) | |

| Histologic Grade | |||

| Low (≥50% Glandular) | 105 (91.3) | 15 (93.8) | 1.000 * |

| High (<50% Glandular) | 10 (8.7) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Adjuvant Therapy | |||

| No | 32 (36.8) | 5 (50) | 0.415 |

| Yes | 55 (63.2) | 5 (50) | |

| Recurrence | |||

| No | 82 (71.3) | 6 (37.5) | 0.007 |

| Yes | 33 (28.7) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | Ref. | - | - |

| Male | 1.168 | 0.498–2.741 | 0.722 |

| Age | |||

| ≤70 Years | Ref. | - | - |

| >70 Years | 1.136 | 0.469–2.749 | 0.778 |

| Tumor Location | |||

| Right Colon | Ref. | - | - |

| Left Colon–Rectum | 1.627 | 0.623–4.248 | 0.320 |

| Histology | |||

| NOS | Ref. | - | - |

| Others | 0.947 | 0.296–3.025 | 0.926 |

| pT Stage | |||

| pT3 | Ref. | - | - |

| pT4 (pT4a–pT4b) | 1.217 | 0.514–2.885 | 0.655 |

| Lymphatic Invasion | |||

| Absent | Ref. | - | - |

| Present | 16.513 | 3.506–77.769 | <0.001 |

| Vascular Invasion | |||

| Absent | Ref. | - | - |

| Present | 0.260 | 0.055–1.234 | 0.090 |

| Perineural Invasion | |||

| Absent | Ref. | - | - |

| Present | 2.060 | 0.502–8.447 | 0.316 |

| Tumor Budding | |||

| Low–Intermediate (0–9) | Ref. | - | - |

| High (≥10) | 1.878 | 0.208–16.965 | 0.575 |

| Histologic Grade | |||

| Low (≥50% glandular) | Ref. | - | - |

| High (<50% glandular) | 2.164 | 0.669–6.999 | 0.198 |

| Tumor Stroma | |||

| Low (≤50%) | Ref. | - | - |

| High (>50%) | 4.366 | 1.516–12.576 | 0.006 |

| Adjuvant Therapy | |||

| No | Ref. | - | - |

| Yes | 0.814 | 0.312–2.127 | 0.675 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romo-Navarro, Á.; Ruiz Martín, J.; García-Camacha Gutiérrez, I.; Amo-Salas, M.; Recuero Pradillo, M.; Sánchez-Muñoz, C.; Murillo Lázaro, C.M.; Carabias López, E.; Sánchez Simón, R.; Quimbayo-Arcila, C.; et al. Disease-Free Survival of Patients with Stage II Stroma-Rich Colorectal Adenocarcinomas with Microsatellite Stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411795

Romo-Navarro Á, Ruiz Martín J, García-Camacha Gutiérrez I, Amo-Salas M, Recuero Pradillo M, Sánchez-Muñoz C, Murillo Lázaro CM, Carabias López E, Sánchez Simón R, Quimbayo-Arcila C, et al. Disease-Free Survival of Patients with Stage II Stroma-Rich Colorectal Adenocarcinomas with Microsatellite Stability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411795

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomo-Navarro, Ángel, Juan Ruiz Martín, Irene García-Camacha Gutiérrez, Mariano Amo-Salas, María Recuero Pradillo, César Sánchez-Muñoz, Cristina María Murillo Lázaro, Esperanza Carabias López, Raquel Sánchez Simón, Carlos Quimbayo-Arcila, and et al. 2025. "Disease-Free Survival of Patients with Stage II Stroma-Rich Colorectal Adenocarcinomas with Microsatellite Stability" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411795

APA StyleRomo-Navarro, Á., Ruiz Martín, J., García-Camacha Gutiérrez, I., Amo-Salas, M., Recuero Pradillo, M., Sánchez-Muñoz, C., Murillo Lázaro, C. M., Carabias López, E., Sánchez Simón, R., Quimbayo-Arcila, C., Hernández Martín, Y., Opazo Rodríguez, M.-S., & Campos-Martín, Y. (2025). Disease-Free Survival of Patients with Stage II Stroma-Rich Colorectal Adenocarcinomas with Microsatellite Stability. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11795. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411795