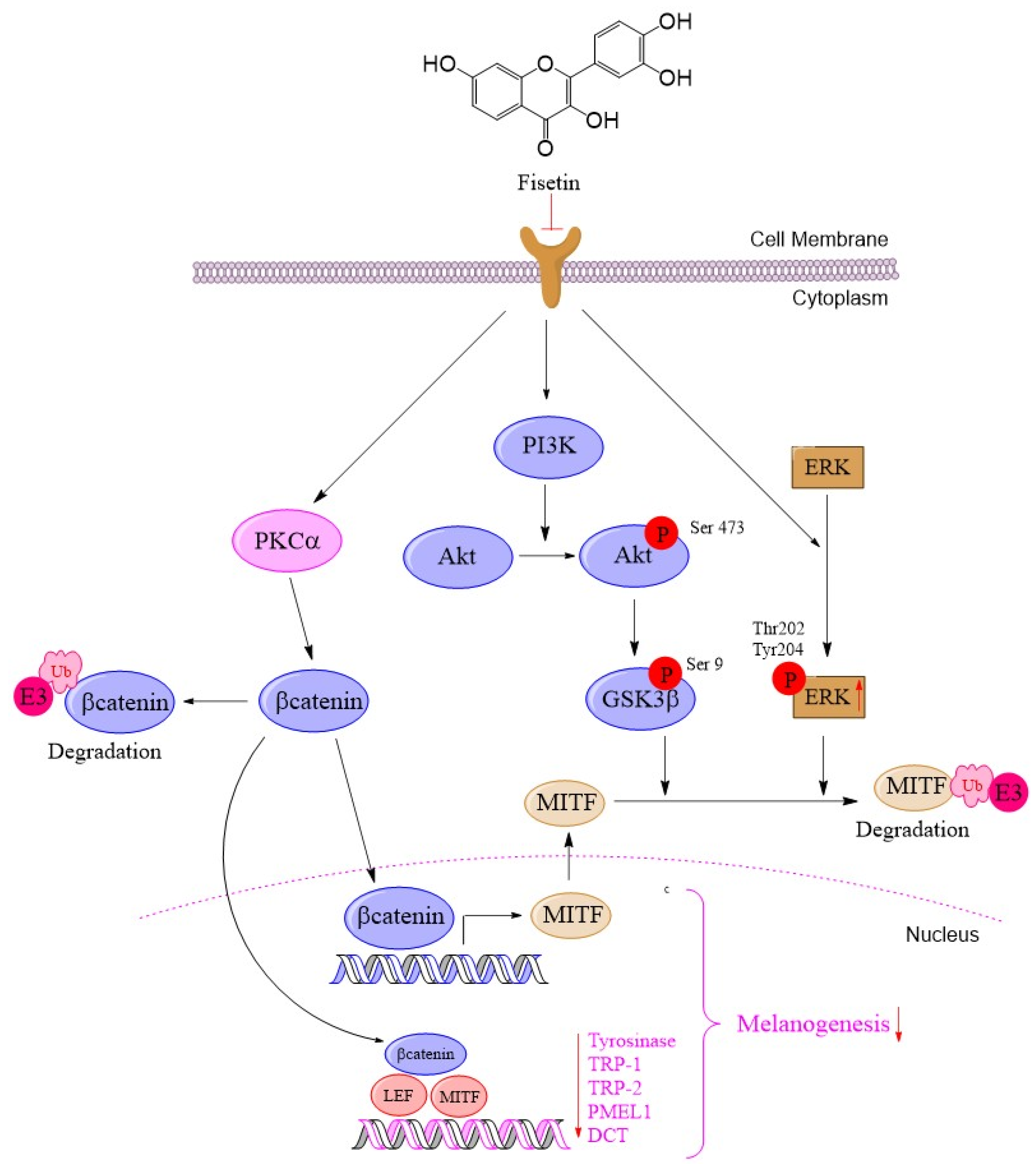

Mechanistic Insights into Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Fisetin: PKCα-Induced β-Catenin Degradation, ERK/MITF Inhibition, and Direct Tyrosinase Suppression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fisetin Reduces Melanin Synthesis in Human Melanoma Cells

2.2. Reduced Cellular Tyrosinase Activity, Melanogenesis-Related Proteins, and mRNA Level in Fisetin-Treated Human Melanoma Cells

2.3. Fisetin Inhibited Melanogenesis Through the Activation of the PKCα Pathway for Induced β-Catenin Degradation

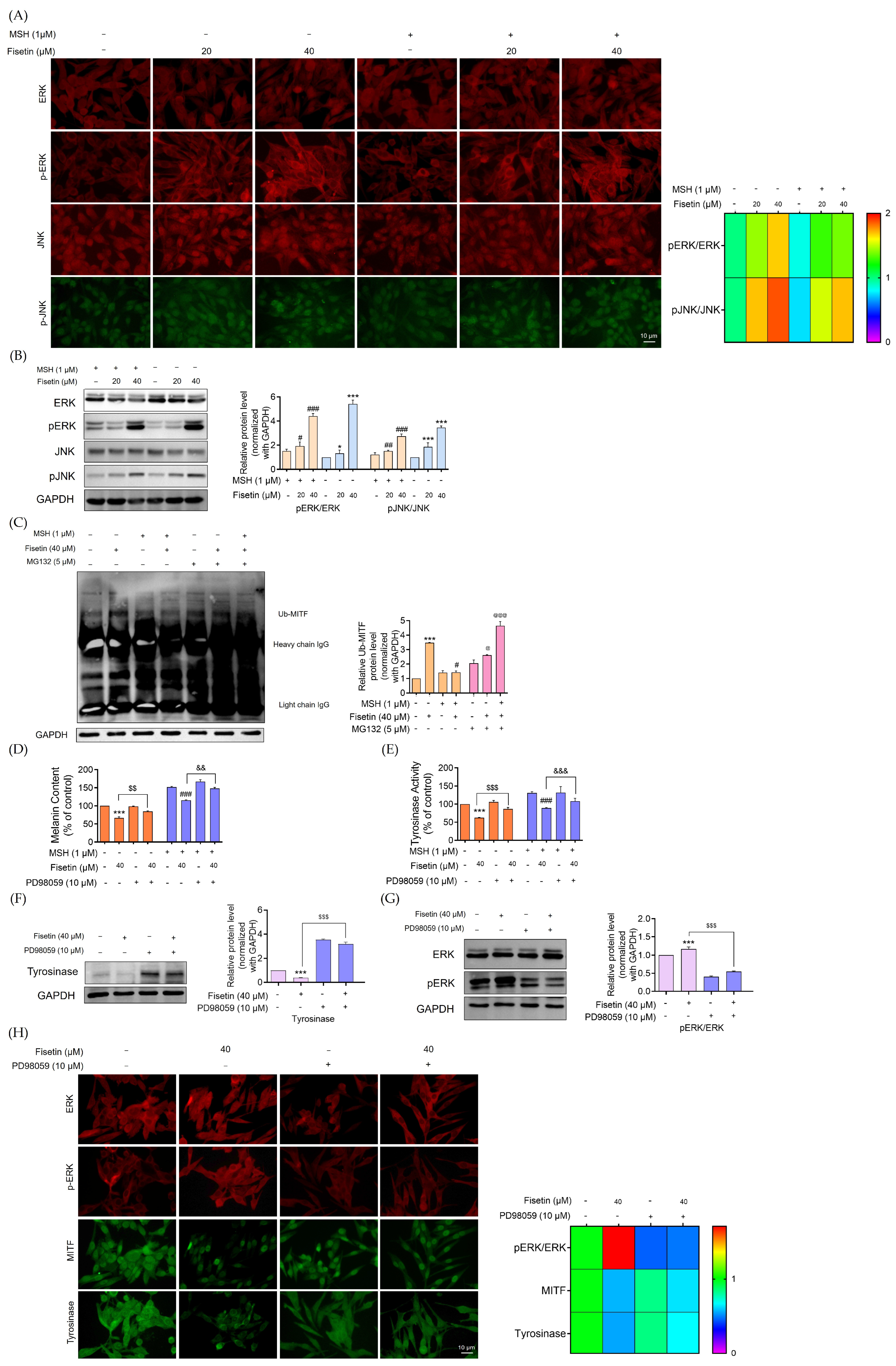

2.4. Fisetin Suppressed Melanogenesis Through the ERK Signaling Pathway, Leading to a Reduction in MITF Degradation

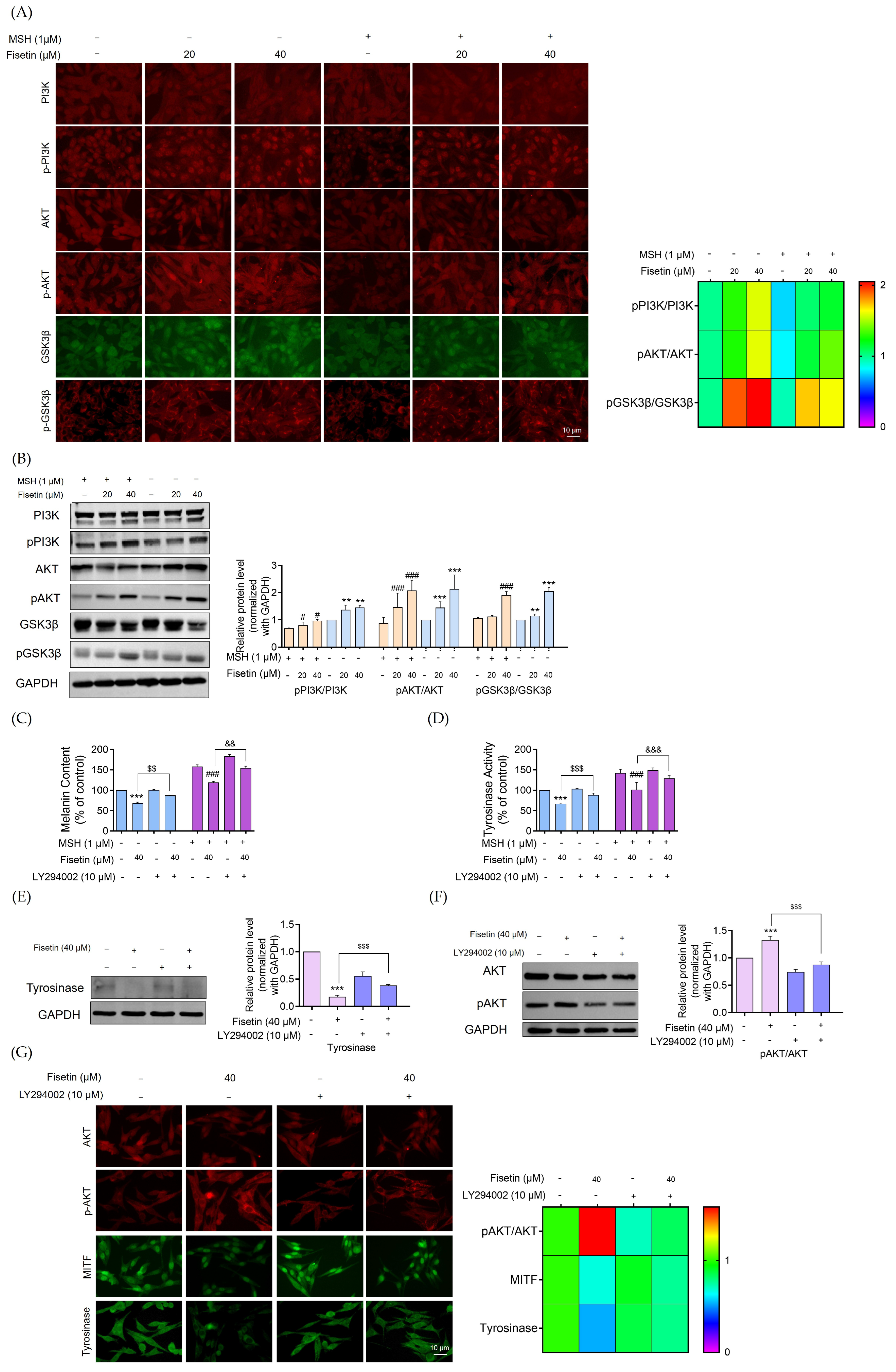

2.5. Fisetin Inhibited Melanogenesis Through the Activation of the AKT/GSK3β Signaling Pathway

2.6. Molecular Docking of Fisetin with Target Proteins

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Reagents and Chemicals

4.3. Preparation of Stock Solution for Fisetin

4.4. Cell Viability Assay

4.5. Cellular Melanin Content Measurement

4.6. Cell-Free Tyrosinase Activity Assay

4.7. Evaluation of Cellular Tyrosinase Activity

4.8. Immunofluorescence

4.9. Quantitative Analysis for Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.10. Western Blot Analysis

4.11. Immunoprecipitation

4.12. Computational Analysis

4.13. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bento-Lopes, L.; Cabaço, L.C.; Charneca, J.; Neto, M.V.; Seabra, M.C.; Barral, D.C. Melanin’s Journey from Melanocytes to Keratinocytes: Uncovering the Molecular Mechanisms of Melanin Transfer and Processing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, F. Melanins: Skin pigments and much more—Types, structural models, biological functions, and formation routes. New J. Sci. 2014, 2014, 498276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mei, H.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, F. The main causes and corresponding solutions of skin pigmentation in the body. J. Dermatol. Sci. Cosmet. Technol. 2024, 1, 100020, Correction in J. Dermatol. Sci. Cosmet. Technol. 2025, 100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ma, W.; Fan, D.; Hu, J.; An, X.; Wang, Z. The biochemistry of melanogenesis: An insight into the function and mechanism of melanogenesis-related proteins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1440187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Hammer, J.A. Melanosome transfer: It is best to give and receive. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahrous, M.H.; Abdel-Dayem, S.I.A.; Adel, I.M.; El-Dessouki, A.M.; El-Shiekh, R.A. Efficacy of Natural Products as Tyrosinase Inhibitors in Hyperpigmentation Therapy: Anti-Melanogenic or Anti-Browning Effects. Chem. Biodivers. 2025, 22, e202403324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, K.U.; Ali, S.A.; Ali, A.S.; Naaz, I. Natural Tyrosinase Inhibitors: Role of Herbals in the Treatment of Hyperpigmentary Disorders. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, G.; Fabrice, J. Tyrosinase related protein 1 (TYRP1/gp75) in human cutaneous melanoma. Mol. Oncol. 2011, 5, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, B.J.; Ben-David, Y. The Role of DCT/TYRP2 in Resistance of Melanoma Cells to Drugs and Radiation. In From Melanocytes to Melanoma: The Progression to Malignancy; Hearing, V.J., Leong, S.P.L., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 577–589. [Google Scholar]

- Widlund, H.R.; Fisher, D.E. Microphthalamia-associated transcription factor: A critical regulator of pigment cell development and survival. Oncogene 2003, 22, 3035–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-S. Natural Melanogenesis Inhibitors Acting Through the Down-Regulation of Tyrosinase Activity. Materials 2012, 5, 1661–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, J.; Cho, M.; Gong, S.-J.; Won, J.; Kim, D.-E.; Kim, E.-Y.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, T.K.; Shin, J.-G.; et al. Protein-kinase-C-mediated beta-catenin phosphorylation negatively regulates the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 4702–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; Kazi, J.U. Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of WNT/Beta-catenin signaling. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 858782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, B.; Pitisci, A.; Catricalà, C.; Larue, L.; Picardo, M. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is stimulated by α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone in melanoma and melanocyte cells: Implication in cell differentiation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011, 24, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellei, B.; Pitisci, A.; Izzo, E.; Picardo, M. Inhibition of melanogenesis by the pyridinyl imidazole class of compounds: Possible involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.A.; Cho, S.K. Phytol suppresses melanogenesis through proteasomal degradation of MITF via the ROS-ERK signaling pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 286, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, J.; Hu, N.; Wang, H. Petanin potentiated JNK phosphorylation to negatively regulate the ERK/CREB/MITF signaling pathway for anti-melanogenesis in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.S.; Cho, J.H.; Lee, H.; Jeong, H.-S.; Kim, M.-K.; Yun, H.-Y.; Kwon, N.S.; Kim, D.-S. Dual hypopigmentary effects of punicalagin via the ERK and Akt pathways. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 92, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhao, L.; Su, Q.; Fan, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Chan, C.B.; Liu, Z. Phosphorylation of MITF by AKT affects its downstream targets and causes TP53-dependent cell senescence. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 80, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Syed, D.N.; Ahmad, N.; Mukhtar, H. Fisetin: A dietary antioxidant for health promotion. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 19, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavenier, J.; Nehlin, J.O.; Houlind, M.B.; Rasmussen, L.J.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; Andersen, O.; Rasmussen, L.J.H. Fisetin as a senotherapeutic agent: Evidence and perspectives for age-related diseases. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2024, 222, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takekoshi, S.; Nagata, H.; Kitatani, K. Flavonoids enhance melanogenesis in human melanoma cells. Tokai J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2014, 39, 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- Molagoda, I.M.N.; Karunarathne, W.A.H.M.; Park, S.R.; Choi, Y.H.; Park, E.K.; Jin, C.-Y.; Yu, H.; Jo, W.S.; Lee, K.T.; Kim, G.-Y. GSK-3β-targeting Fisetin promotes melanogenesis in B16F10 melanoma cells and zebrafish larvae through β-catenin activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, M.S.; Kim, R.H.; Kwon, O.J.; Roh, S.S.; Kim, G.N. Beneficial role and function of Fisetin in skin health via regulation of the CCN2/TGF-β signaling pathway. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25 (Suppl. 1), 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, D.N.; Afaq, F.; Maddodi, N.; Johnson, J.J.; Sarfaraz, S.; Ahmad, A.; Setaluri, V.; Mukhtar, H. Inhibition of human melanoma cell growth by the dietary flavonoid Fisetin is associated with disruption of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and decreased Mitf levels. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1291–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promden, W.; Viriyabancha, W.; Monthakantirat, O.; Umehara, K.; Noguchi, H.; De-Eknamkul, W. Correlation between the potency of flavonoids on mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory activity and melanin synthesis in melanocytes. Molecules 2018, 23, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Hyun, C.G. Imperatorin Positively Regulates Melanogenesis through Signaling Pathways Involving PKA/CREB, ERK, AKT, and GSK3β/β-Catenin. Molecules 2022, 27, 6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhu, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, Q. Recent advances in PKC inhibitor development: Structural design strategies and therapeutic applications. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 287, 117290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, D.; Mayer, M.; Zahn, S.K.; Zeeb, M.; Wöhrle, S.; Bergner, A.; Bruchhaus, J.; Ciftci, T.; Dahmann, G.; Dettling, M.; et al. Getting a Grip on the Undrugged: Targeting β-Catenin with Fragment-Based Methods. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1420–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Shang, C.; Han, M.; Chen, C.; Tang, W.; Liu, W. Inhibitory mechanism of scutellarein on tyrosinase by kinetics, spectroscopy and molecular simulation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 296, 122644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, M.; Hearing, V.J. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 2008, 84, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, D.; Fang, Z.; Zhang, P. The melanin inhibitory effect of plants and phytochemicals: A systematic review. Phytomedicine 2022, 107, 154449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Włoch, A.; Strugała-Danak, P.; Pruchnik, H.; Krawczyk-Łebek, A.; Szczecka, K.; Janeczko, T.; Kostrzewa-Susłow, E. Interaction of 4′-methylflavonoids with biological membranes, liposomes, and human albumin. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 16003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, R.; Soni, P.; Sharma, M.; Prasher, P.; Kaverikana, R.; Mangalpady, S.S.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Calina, D. Fisetin as a chemoprotective and chemotherapeutic agent: Mechanistic insights and future directions in cancer therapy. Med. Oncol. 2025, 42, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denat, L.; Kadekaro, A.L.; Marrot, L.; Leachman, S.A.; Abdel-Malek, Z.A. Melanocytes as instigators and victims of oxidative stress. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, Y.; Hariu, A.; Kato, C.; Seiji, M. Radical production during tyrosinase reaction, dopa-melanin formation, and photoirradiation of dopa-melanin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1984, 82, 573–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land, E.J.; Ramsden, C.A.; Riley, P.A. Quinone chemistry and melanogenesis. Methods Enzym. 2004, 378, 88–109. [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Smith, F.; Meyskens, F.L. Molecular mechanisms of flavonoids in melanin synthesis and the potential for the prevention and treatment of melanoma. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 1264–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelmi, M.C.; Houtzagers, L.E.; Strub, T.; Krossa, I.; Jager, M.J. MITF in Normal Melanocytes, Cutaneous and Uveal Melanoma: A Delicate Balance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Mello, S.A.; Finlay, G.J.; Baguley, B.C.; Askarian-Amiri, M.E. Signaling Pathways in Melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Hemesath, T.J.; Takemoto, C.M.; Horstmann, M.A.; Wells, A.G.; Price, E.R.; Fisher, D.Z.; Fisher, D.E. c-Kit triggers dual phosphorylations, which couple activation and degradation of the essential melanocyte factor Mi. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B.; Singh, S.K.; Sarkar, C.; Bera, R.; Ratha, J.; Tobin, D.J.; Bhadra, R. Activation of the Mitf promoter by lipid-stimulated activation of p38-stress signalling to CREB. Pigment Cell Res. 2006, 19, 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirasugi, I.; Kamada, M.; Matsui, T.; Sakakibara, Y.; Liu, M.C.; Suiko, M. Sulforaphane inhibited melanin synthesis by regulating tyrosinase gene expression in B16 mouse melanoma cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2010, 74, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oka, M.; Nagai, H.; Ando, H.; Fukunaga, M.; Matsumura, M.; Araki, K.; Ogawa, W.; Miki, T.; Sakaue, M.; Tsukamoto, K.; et al. Regulation of melanogenesis through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway in human G361 melanoma cells. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2000, 115, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Hong, A.R.; Kim, Y.H.; Yoo, H.; Kang, S.W.; Chang, S.E.; Song, Y. JNK suppresses melanogenesis by interfering with CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 3-dependent MITF expression. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.; Nikolakaki, E.; Plyte, S.E.; Totty, N.F.; Woodgett, J.R. Modulation of the glycogen synthase kinase-3 family by tyrosine phosphorylation. Embo J. 1993, 12, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frame, S.; Cohen, P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem. J. 2001, 359, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, M.; Larribere, L.; Bille, K.; Aberdam, E.; Ortonne, J.-P.; Ballotti, R.; Bertolotto, C. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta is activated by cAMP and plays an active role in the regulation of melanogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 33690–33697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, M.; Yu, X.; Teng, B.; Schroder, P.; Haller, H.; Eschenburg, S.; Schiffer, M. Protein kinase C ϵ stabilizes β-catenin and regulates its subcellular localization in podocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 12100–12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, M.L.; Czyz, M. MITF in melanoma: Mechanisms behind its expression and activity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picq, M.; Dubois, M.; Munari-Silem, Y.; Prigent, A.F.; Pacheco, H. Flavonoid modulation of protein kinase C activation. Life Sci. 1989, 44, 1563–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, J.; Ramani, R.; Suraju, M.O. Polyphenol compounds and PKC signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860, 2107–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Thampi, A.; Puranik, M. Kinetics of melanin polymerization during enzymatic and nonenzymatic oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 2047–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, X.T.; Park, S.H.; Lee, Y.G.; Jeong, H.Y.; Moon, J.H.; Jeon, T.I. Protocatechuic Acid from Pear Inhibits Melanogenesis in Melanoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Fu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Yang, Y.; Song, G.; Yun, C.; Gao, R. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits melanogenesis, melanocyte dendricity and melanosome transport by regulating ERK-mediated MITF degradation. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; von Matt, P.; Sedrani, R.; Albert, R.; Cooke, N.; Ehrhardt, C.; Geiser, M.; Rummel, G.; Stark, W.; Strauss, A.; et al. Discovery of 3-(1 H-indol-3-yl)-4-[2-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl) quinazolin-4-yl] pyrrole-2, 5-dione (AEB071), a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C isotypes. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6193–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismaya, W.T.; Rozeboom, H.J.; Weijn, A.; Mes, J.J.; Fusetti, F.; Wichers, H.J.; Dijkstra, B.W. Crystal structure of Agaricus bisporus mushroom tyrosinase: Identity of the tetramer subunits and interaction with tropolone. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 5477–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Wichers, H.J.; Soler-Lopez, M.; Dijkstra, B.W. Structure of human tyrosinase related protein 1 reveals a binuclear zinc active site important for melanogenesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 9812–9815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S.K.; Bhatt, R.; Bhikadiya, C.; Bi, C.; Biester, A.; Biswas, P.; Bittrich, S.; Blaumann, S.; Brown, R.; Chao, H.; et al. Updated resources for exploring experimentally-determined PDB structures and Computed Structure Models at the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D564–D574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E.F.; Goddard, T.D.; Huang, C.C.; Meng, E.C.; Couch, G.S.; Croll, T.I.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D1516–D1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNutt, A.T.; Francoeur, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Masuda, T.; Meli, R.; Ragoza, M.; Sunseri, J.; Koes, D.R. GNINA 1.0: Molecular docking with deep learning. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNutt, A.T.; Li, Y.; Meli, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Koes, D.R. GNINA 1.3: The next increment in molecular docking with deep learning. J. Cheminform. 2025, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ei, Z.Z.; Racha, S.; Zou, H.; Chanvorachote, P. Mechanistic Insights into Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Fisetin: PKCα-Induced β-Catenin Degradation, ERK/MITF Inhibition, and Direct Tyrosinase Suppression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311739

Ei ZZ, Racha S, Zou H, Chanvorachote P. Mechanistic Insights into Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Fisetin: PKCα-Induced β-Catenin Degradation, ERK/MITF Inhibition, and Direct Tyrosinase Suppression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311739

Chicago/Turabian StyleEi, Zin Zin, Satapat Racha, Hongbin Zou, and Pithi Chanvorachote. 2025. "Mechanistic Insights into Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Fisetin: PKCα-Induced β-Catenin Degradation, ERK/MITF Inhibition, and Direct Tyrosinase Suppression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311739

APA StyleEi, Z. Z., Racha, S., Zou, H., & Chanvorachote, P. (2025). Mechanistic Insights into Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Fisetin: PKCα-Induced β-Catenin Degradation, ERK/MITF Inhibition, and Direct Tyrosinase Suppression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11739. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311739