1. Introduction

Adipose tissue serves as a central regulator of systemic energy homeostasis by balancing lipid storage and mobilization. This dynamic equilibrium is maintained through two opposing but coordinated processes: adipogenesis, the differentiation of preadipocytes into lipid-storing adipocytes, and lipolysis, the hydrolysis of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol for energy utilization. Dysregulation of these processes leads to abnormal lipid accumulation and adipocyte hypertrophy, contributing to metabolic dysfunction associated with obesity and insulin resistance [

1,

2]. At the molecular level, adipocyte differentiation and lipid turnover are governed by a complex network of transcriptional and enzymatic regulators. Among them, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα) are master transcription factors that orchestrate the adipogenic gene expression program, whereas adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) catalyze key steps of lipolysis [

3,

4]. Therefore, maintaining the proper balance between adipogenic activation and lipolytic signaling is critical for adipose tissue homeostasis and metabolic health [

5,

6,

7].

Nanosized extracellular vesicles (EVs), typically 30–150 nm in diameter, mediate intercellular communication by transferring bioactive cargos such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [

8]. EVs participate in diverse physiological and pathological processes, including immune modulation, inflammation, and metabolic regulation. Among various sources, EVs derived from probiotic bacteria have gained growing interest for their ability to influence host cellular functions and metabolic homeostasis [

9,

10].

Lactobacillus rhamnosus, a well-characterized probiotic species, is widely recognized for its beneficial effects on gut health and immune regulation [

11]. Recent research has extended this interest to the vesicles secreted by

L. rhamnosus, which are increasingly considered bioactive mediators with functional relevance beyond the gut.

Several studies have demonstrated that

L. rhamnosus-derived EVs can exert regulatory effects on host cells. For example, EVs from

L. rhamnosus GG have been reported to modulate osteoblast–osteoclast balance and regulate bone microenvironment signaling in osteoporosis models, partly through the delivery of functional RNA cargos [

12]. In addition, EVs derived from

L. rhamnosus GG have been shown to carry bioactive molecules such as lipoteichoic acids and cell cycle-regulatory factors, which can influence immune signaling, cellular proliferation, and apoptosis in cancer-related settings [

13]. These findings collectively support the concept that

L. rhamnosus EVs function as postbiotic effectors capable of modulating host signaling pathways and cellular metabolism.

In parallel, emerging evidence suggests that probiotic-derived EVs may contribute more broadly to metabolic regulation. For instance, EVs from

Lactobacillus plantarum were shown to alleviate diet-induced metabolic dysfunction in mice by improving hepatic lipid metabolism and enhancing AMPK signaling [

14]. Together with other emerging reports, these findings suggest that probiotic EVs may broadly contribute to metabolic homeostasis. In this study, we hypothesized that EVs derived from

L. rhamnosus may act directly on adipocytes to regulate adipogenesis and lipid turnover at the cellular level. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of

L. rhamnosus BS-Pro-08-derived EVs (hereafter referred to as Lacto EV) on adipogenic differentiation and lipolysis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and explored their underlying molecular mechanisms through proteomic profiling.

3. Discussion

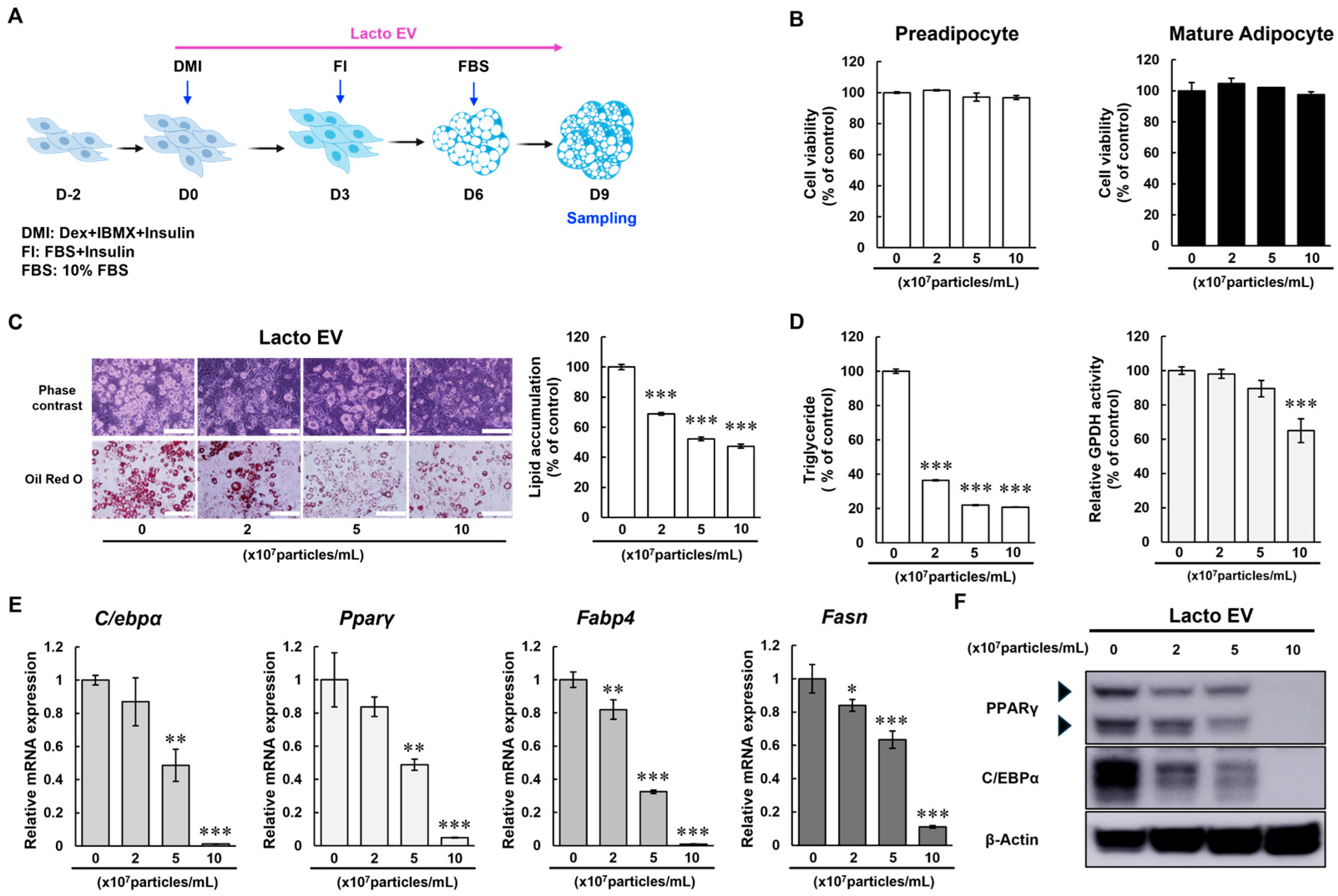

In this study, we investigated the potential of extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from

Lactobacillus rhamnosus BS-Pro-08 (Lacto EV) on adipocyte differentiation and lipid metabolism. Our findings demonstrate that Lacto EV suppresses the early stages of adipogenesis by reducing the expression of C/EBPα and PPARγ, thereby inhibiting the differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes. Both C/EBPα and PPARγ are master transcriptional regulators that initiate and coordinate the gene expression program required for preadipocyte commitment and lipid accumulation, and their downregulation at this early stage is a critical intervention point to prevent subsequent adipose tissue expansion [

19]. Early-stage inhibition is particularly important because it may limit clonal expansion and terminal differentiation, which are largely irreversible steps in adipocyte development [

20]. The concurrent downregulation of downstream adipogenic markers such as fatty acid synthase (FASN) and fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) further supports the inhibitory effect of Lacto EV on the adipogenic pathway.

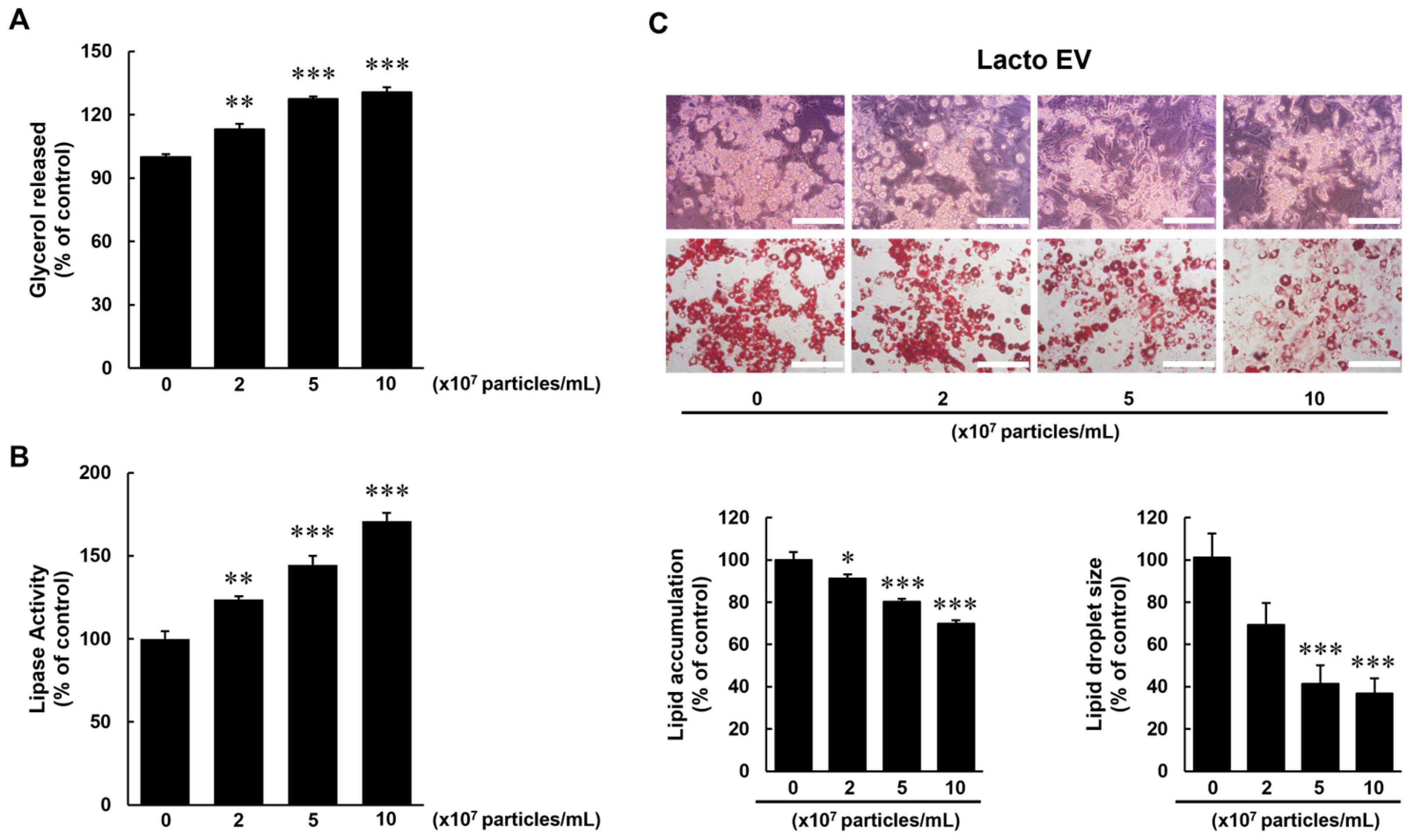

In addition to its anti-adipogenic properties, Lacto EV enhanced lipolysis, as evidenced by a dose-dependent increase in glycerol release and lipase activity, indicating promotion of triglyceride breakdown in mature adipocytes (

Figure 4). Lipolysis plays a central role in energy mobilization and is critical in maintaining metabolic flexibility, both of which are often impaired in obesity [

21]. Enhanced lipolytic activity has also been associated with reduced adiposity [

22]. Interestingly, despite these functional outcomes, the protein levels of endogenous lipolytic markers, including ATGL, total HSL, and phosphorylated HSL, were reduced (

Figure S1). This finding suggests that Lacto EV may promote an EV-enhanced lipolytic response that is not fully explained by classical ATGL/HSL signaling and may involve alternative mechanisms.

Our proteomic analysis identified several EV-associated proteins that could contribute to these effects (

Figure S2). Through the application of tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling and subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis, a total of 1228 proteins were identified. Based on their functional annotations and biological relevance to adipogenic regulation, 11 proteins were selected as potential anti-adipogenic candidates. In particular, the enrichment of GDSL-like lipase and α/β hydrolase proteins within EVs is consistent with the hypothesis that exogenous enzymatic activities may participate in triglyceride hydrolysis, potentially complementing or modulating host lipolytic pathways.

GDSL/SGNH hydrolases are characterized by a conserved GDS(L) motif and a canonical SGNH catalytic fold, exhibiting broad substrate specificity toward neutral lipids and phospholipids. These enzymes underpin microbial lipolytic activities, and bacterial lipases and phospholipases are known to remodel host lipid environments in various contexts, potentially affecting lipid homeostasis [

23,

24,

25,

26]. Similarly, α/β hydrolases comprise a broad class of esterases and lipases capable of hydrolyzing glycerides and reshaping host lipid pools [

24,

27]. Although we did not directly measure the enzymatic activities of these individual proteins in this study, their presence in Lacto EV provides a plausible molecular basis for the observed EV-enhanced lipolytic response in adipocytes.

This dual action—suppressing early adipogenic differentiation while promoting triglyceride breakdown in mature adipocytes—suggests that Lacto EV may influence adipocyte function through complementary molecular pathways. By concurrently attenuating transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis (PPARγ and C/EBPα) and engaging EV-associated hydrolases that could facilitate triglyceride hydrolysis, Lacto EV appears to modulate both lipid storage and mobilization within adipocytes. Such coordinated regulation is consistent with the concept that EVs act as multi-targeted mediators of metabolic signaling rather than acting through a single pathway.

Collectively, these findings indicate that functional proteins carried by Lacto EVs are likely involved in the regulation of adipogenesis and lipolysis, supporting the concept that bacterial EVs act as bioactive effectors capable of modulating host metabolic signaling. These observations align with emerging evidence that

Lactobacillus-derived EVs can affect host metabolic processes [

14]. Our results further expand this understanding by demonstrating the direct cellular actions of

L. rhamnosus EVs on adipocyte differentiation and lipolysis.

Taken together, these findings suggest that probiotic-derived EVs such as Lacto EV may serve as bioactive modulators of adipocyte biology that are relevant to obesity and related metabolic disorders. A limitation of this study is that all experiments were conducted in 3T3-L1 adipocytes, and the in vivo relevance of Lacto EV therefore remains to be established. In addition, because our EV purification workflow did not incorporate cytoplasmic negative markers or density-gradient fractionation, further work implementing these approaches will be required to strengthen EV purity assessment in accordance with MISEV2018 recommendations. Further studies are warranted to identify the specific functional components within Lacto EV responsible for these effects and to evaluate their activities, safety, and mechanisms in appropriate in vivo models. Such investigations will be essential to determine whether these vesicles, or their key molecular constituents, can be developed into practical strategies for managing obesity-associated metabolic dysregulation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain Isolation

Kefir grains were washed with sterilized distilled water, suspended, and diluted in sterilized saline solution. The diluted samples were plated onto MRS agar (BD Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) plates supplemented with 1% CaCO3 and incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 48 h. Colonies producing yellow pigmentation and clear zones were presumed to be lactic acid bacteria and were subsequently isolated in pure culture. The strain was identified using 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and BLAST analysis (BLASTN 2.13.0+) determined the strain as Lactobacillus rhamnosus. The strain was designated as L. rhamnosus BS-Pro-08.

4.2. Preparation of Extracellular Vesicles and Characteristics

L. rhamnosus BS-Pro-08 (accession number: KCTC 15876BP) was subcultured in a modified MRS medium (Biospectrum, Yongin, Republic of Korea) prepared from plant-based ingredients and then inoculated at 1% (v/v). The culture was incubated anaerobically at 37 °C for 60 h. The culture supernatant was harvested following centrifugation at 15,000× g and 4 °C for 25 min and filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane using vacuum filtration to remove large particles. A subsequent filtration with a 0.22 µm membrane was performed to eliminate residual bacteria. The resulting filtrate was concentrated 15-fold using an Amicon® Ultra-15 system (100 kDa MWCO) (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and washed with 0.1 µm filtered distilled water. To further remove residual soluble components and enrich EVs, the sample was then concentrated once more using the same Amicon® Ultra-15 device (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). The purified Lactobacillus-derived extracellular vesicles (Lacto EV) were stored at −80 °C until use.

The concentration and size profile of the Lacto EV were assessed using nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) instrument (ZetaView PMX-120) (Particle Metrix, Inning am Ammersee, Germany). During measurement, optimal camera and laser alignment was ensured, and auto-symmetry adjustments were performed. The Lacto EV sample was serially diluted 1:800 in 0.1 µm filtered purified water to obtain approximately 150–200 particles per frame. The analysis was based on measurements from 11 positions conducted at 23.5 °C. Key instrumental parameters included a camera sensitivity of 80, a shutter speed of 100, 30 fps video capture (medium quality), and a particle detection area gated from 10 to 1000. All data was processed using the ZetaView software (Version 8.06.01 SP1).

For structural characterization, Lacto EV samples were prepared for transmission electron microscopy. Samples were applied to 300-mesh copper grids followed by negative staining with a 2% uranyl acetate solution. A JEM-2100Plus transmission electron microscope (JEOL Inc., Tokyo, Japan) operating at 200 kV was used to capture the electron micrographs.

4.3. Cell Culture and Differentiation

3T3-L1 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The culture media components, including Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), bovine calf serum (BCS), and penicillin-streptomycin (PS), were acquired from Welgene (Welgene, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea). Insulin, dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA). 3T3-L1 fibroblasts were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% BCS at a in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. 3T3-L1 cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well and cultured until confluence, thereby inducing cell cycle arrest. Differentiation was induced with 500 μM IBMX, 2.5 μM dexamethasone, and 10 μg/mL insulin (DMI cocktail) in 10% FBS/DMEM for 3 days. The medium was then replaced with 10% FBS/DMEM containing 10 μg/mL insulin. On day 6, the cells were re-fed with 10% FBS/DMEM without insulin for 3 days. Unless otherwise stated, all in vitro experiments were conducted using Lacto EV at concentrations ranging from 0 to 1 × 108 particles/mL. The specific concentrations applied in each experiment are indicated in the corresponding figure legends.

4.4. MTT Assay

Preadipocytic 3T3-L1 cells and mature adipocytes were exposed to Lacto EV for 72 h and then treated with 100 μg/mL MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) in serum-free DMEM at 37 °C for 3 h. The media was discarded, and the accumulated formazan was solubilized by adding DMSO to the cells. Subsequently, absorbance was quantified at a wavelength of 570 nm using a multi-well plate reader.

4.5. Oil Red O Staining

Differentiated 3T3-L1 cells were washed once with DPBS (Welgene, Gyeongsan, Republic of Korea) and fixed with DPBS containing 4% formaldehyde for at least 30 min. Oil Red O Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA) was mixed with HPLC grade water at a 6:4 ratio to prepare the working solution, which was applied to fixed cells and stained for 45 min at ambient temperature. Once the staining step was completed, residual dye was removed by rinsing the cells five times with distilled water, after which the plates were allowed to dry completely and the bound dye was subsequently eluted with 100% 2-propanol. The absorbance was measured at 540 nm wavelength by using a multi-well plate reader.

4.6. Triglyceride (TG) Measurement

After discarding the medium, cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold DPBS and subsequently harvested in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1mM EDTA. The pellet was sonicated for three cycles of 15 s at 20% amplitude using UP50H with MS7 (Hielscher ultrasonic GmbH, Teltow, Germany). The lysate was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 10 min prior to collecting the supernatant. TG content was measured using a TG colorimetric assay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

4.7. GPDH Activity Assay

Cells were suspended in 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) with 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol. Cells were lysed by sonication and then centrifuged at 12,000× g for 20 min at 4 °C to obtain the supernatant, which was assayed using GPDH assay kit (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan).

4.8. Glycerol Release Assay

3T3-L1 adipocytes were fully differentiated by day 9 (D9) and subsequently incubated in serum-free medium for 16 h. Following overnight incubation, cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of Lacto EV for 24 h. The amount of free glycerol released into the culture supernatant was measured using a Glycerol Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) as directed by the kit manufacturer.

4.9. Lipase Activity Assay

Cells were rinsed twice with ice-cold DPBS, and lipase activity was assessed using the Lipase Activity Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were harvested with 1× assay buffer and homogenized by sonication. After centrifugation at 10,000× g at 4 °C, the supernatant was used for the activity assay.

4.10. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

To evaluate the mRNA expression level of

C/EBPα,

PPARγ,

FASN,

FABP4 and

PPIA, total RNA was prepared using the miniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). A total of 2 μg of the extracted RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using amfiRivert cDNA Synthesis Platinum Master Mix (GenDEPOT, Katy, TX, USA). qRT-PCR was performed using a CronoSTAR

TM (TaKaRa Bio, Shiga, Japan). Normalization was carried out using

PPIA as the internal control. The primer sequences employed throughout this investigation are presented in

Table 1.

4.11. Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysate was prepared with Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) containing 1 mM PMSF. Equal amounts of protein (30 µg per lane) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against OMP-A, LTA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA), TSG101 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), HSL, phospho-HSL, C/EBPα, PPARγ (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), ATGL, β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). Afterwards, membranes were developed using HRP-conjugated IgG secondary antibody and HRP chemiluminescent substrates (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA).

4.12. Proteomic Analysis

Proteomic profiling of EV was performed by Bertis Inc. (Gwacheon, Republic of Korea) using a Nano-LC Ultimate 3000 system/Thermo FAIMS Pro™ Orbitrap Exploris 480 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Data-dependent acquisition performed and processed using SAGE software (version 0.14.7). Protein identification was carried out by matching the acquired mass spectra to L. rhamnosus protein sequences (Organism ID: 47715) in the UniProt database.

4.13. Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SD or SEM, as indicated. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, and differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.