Enhancing Secondary Metabolite Production in Actinobacteria Through Over-Expression of a Medium-Sized SARP Regulator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

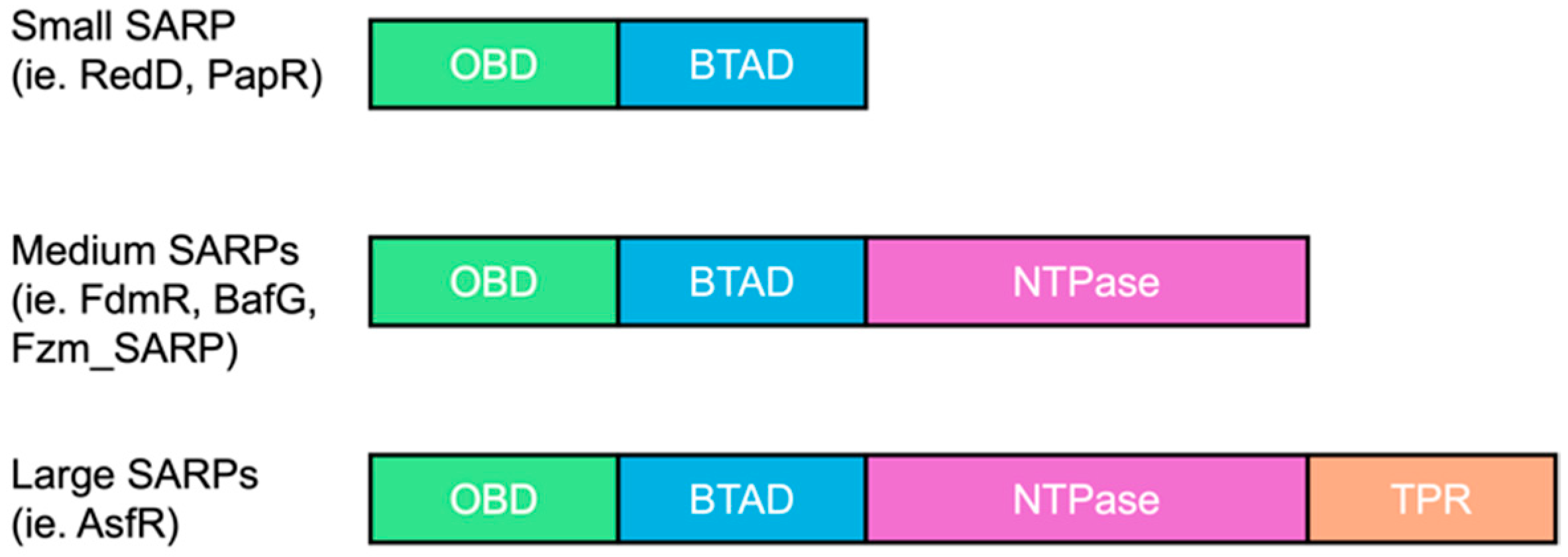

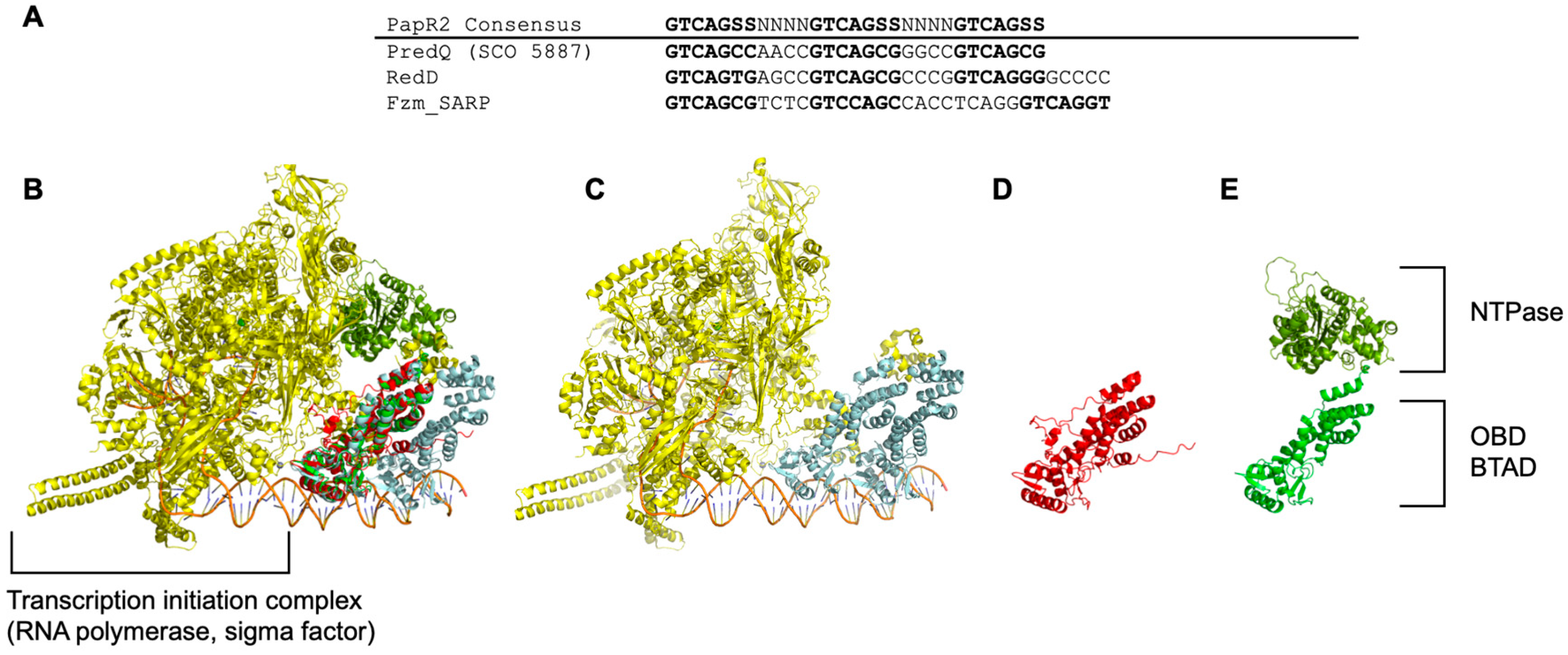

2.1. In Silico SARP Comparisons

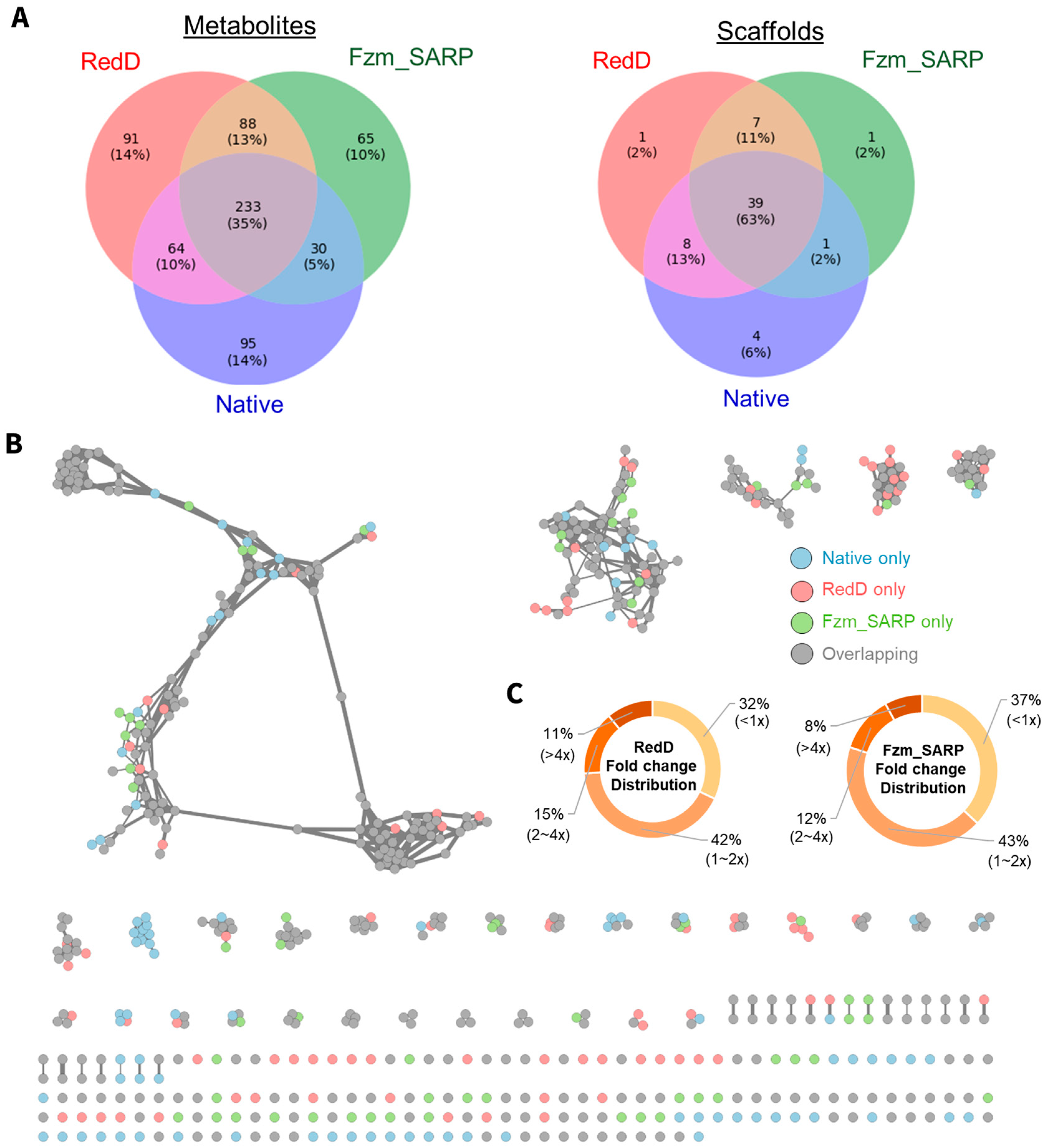

2.2. Comparison of Activation Potentials Across Actinobacteria

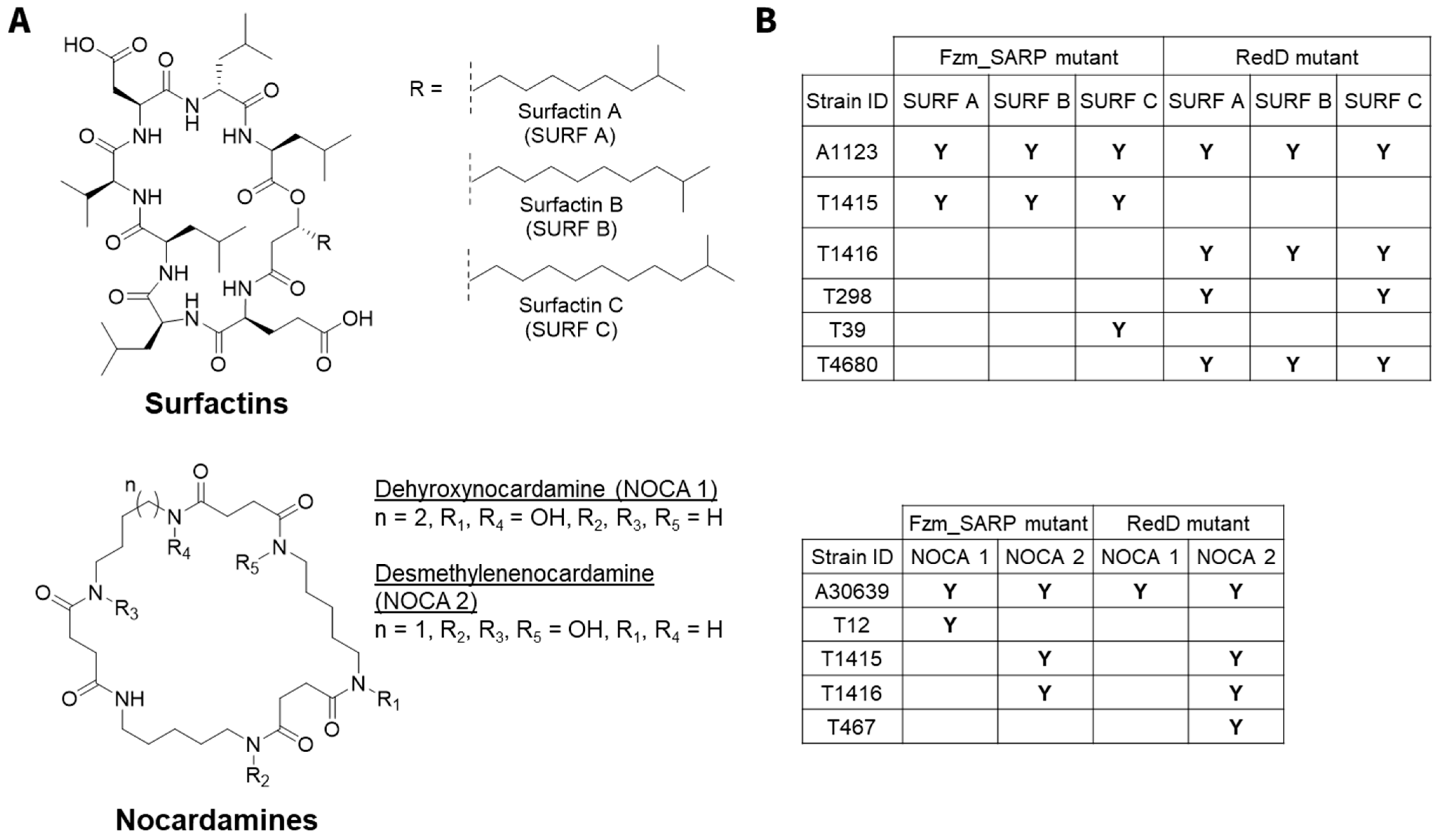

2.3. Case Study: Surfactins and Nocardamines

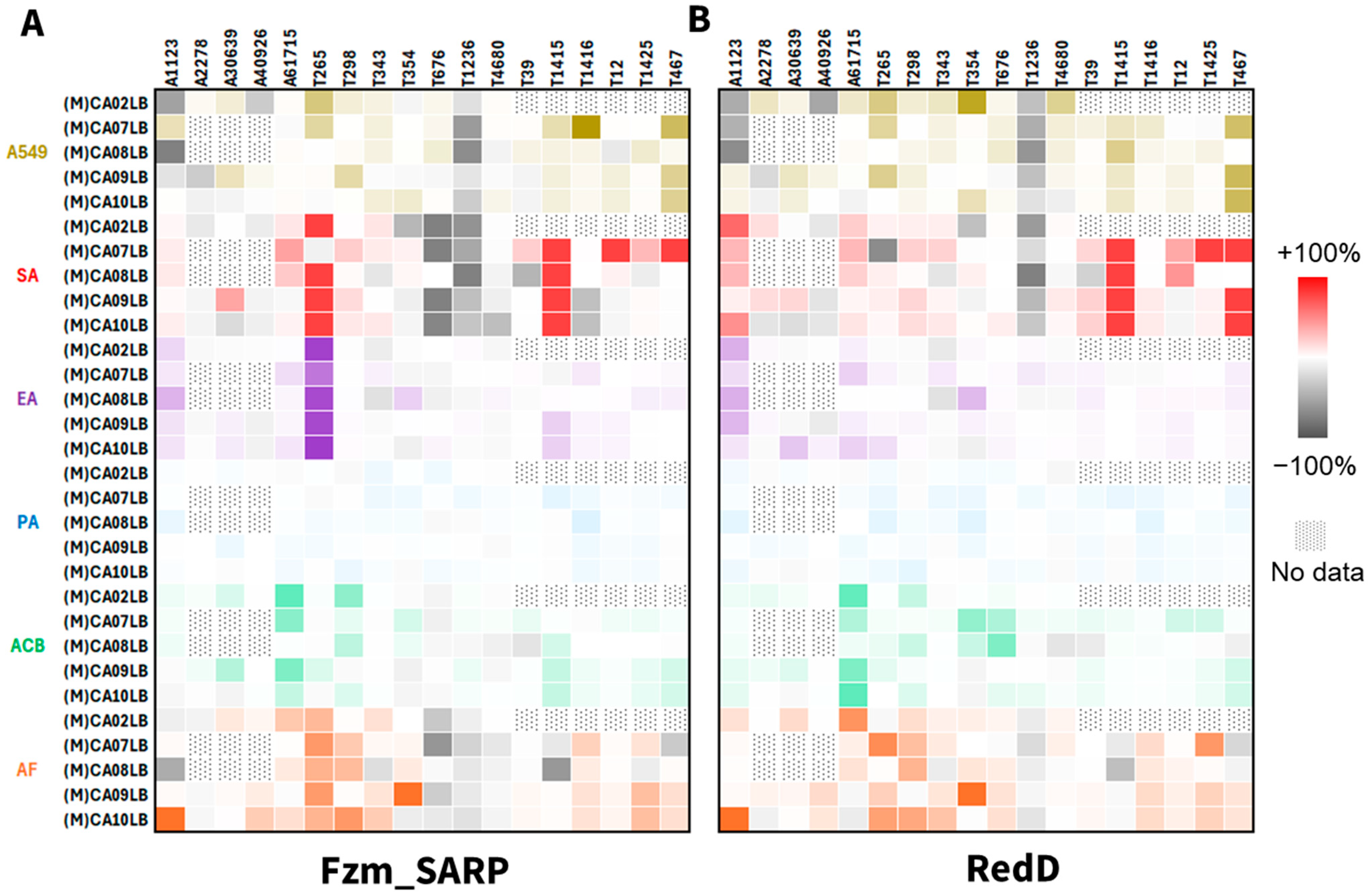

2.4. Bioactivity Comparison

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mutant Generation

4.2. Cultivation

4.3. Liquid Chromatography—Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Analysis

4.4. Metabolite and Bioactivity Comparisons

4.5. Molecular Networking Analysis

4.6. Comparison of Metabolite Production Fold Change Between Wild-Type and Mutant Strains

4.7. Biological Assays

4.8. Binding Motif Prediction

4.9. Structure Modeling and Alignment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; International Natural Product Sciences Taskforce; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B. A New Golden Age of Natural Products Drug Discovery. Cell 2015, 163, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbal, L.; Marques, F.; Nadmid, S.; Mendes, M.V.; Luzhetskyy, A. Secondary metabolites overproduction through transcriptional gene cluster refactoring. Metab. Eng. 2018, 49, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Liu, X.; Tang, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Liang, S. CRISETR: An efficient technology for multiplexed refactoring of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 11378–11393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, J.; Yoshikuni, Y. Multi-chassis engineering for heterologous production of microbial natural products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 62, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Zhu, T.F. Targeted isolation and cloning of 100-kb microbial genomic sequences by Cas9-assisted targeting of chromosome segments. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 960–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Maclntyre, L.W.; Brady, S.F. Refactoring biosynthetic gene clusters for heterologous production of microbial natural products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 69, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, B.; Kim, D.G.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.U.; Oh, M.K. Heterologous overproduction of oviedomycin by refactoring biosynthetic gene cluster and metabolic engineering of host strain Streptomyces coelicolor. Microb. Cell Factories 2023, 22, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, L.; Hemu, X.; Tan, N.H.; Wang, Z. OSMAC Strategy: A promising way to explore microbial cyclic peptides. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 268, 116175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Choe, D.; Palsson, B.O.; Cho, B. Machine-Learning Analysis of Streptomyces coelicolor Transcriptomes Reveals a Transcription Regulatory Network Encompassing Biosynthetic Gene Clusters. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2403912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Sigrist, R.; Petrov, M.S.; Marcussen, N.; Gren, T.; Palsson, B.O.; Yang, L.; Özdemir, E. Machine Learning Uncovers the Transcriptional Regulatory Network for the Production Host Streptomyces albidoflavus. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.H.; Wong, F.T.; Yeo, W.L.; Ching, K.C.; Lim, Y.W.; Heng, E.; Chen, S.; Tsai, D.; Lauderdale, T.; Shia, K.; et al. Auroramycin: A Potent Antibiotic from Streptomyces roseosporus by CRISPR-Cas9 Activation. ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 1716–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.M.; Wong, F.T.; Wang, Y.; Luo, S.; Lim, Y.H.; Heng, E.; Yeo, W.L.; Cobb, R.E.; Enghiad, B.; Ang, E.L.; et al. CRISPR–Cas9 strategy for activation of silent Streptomyces biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 607–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, D.W.P.; Tan, L.L.; Heng, E.; Zulkarnain, N.; Ching, K.C.; Wibowo, M.; Chin, E.J.; Tan, Z.Y.Q.; Leong, C.Y.; Ng, V.W.P.; et al. Exploring a general multi-pronged activation strategy for natural product discovery in Actinomycetes. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Grkovic, T.; Liu, X.; Han, J.; Zhang, L.; Quinn, R.J. A systems approach using OSMAC, Log P and NMR fingerprinting: An approach to novelty. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2017, 2, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, S.; Jackson, S.A.; Patry, S.; Dobson, A.D.W. Extending the “one strain many compounds” (OSMAC) principle to marine microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, J.; Hubmann, G.; Rosenthal, K.; Lütz, S. Triaging of culture conditions for enhanced secondary metabolite diversity from different bacteria. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, N.; Choe, D.; Lee, Y.; Kim, W.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, G.; Kim, H.; Ahn, N.-H.; Lee, B.-H.; et al. System-Level Analysis of Transcriptional and Translational Regulatory Elements in Streptomyces griseus. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 844200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Xia, H. The roles of SARP family regulators involved in secondary metabolism in Streptomyces. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1368809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.; Handayani, I.; Blin, K.; Kulik, A.; Mast, Y. Disclosing the Potential of the SARP-Type Regulator PapR2 for the Activation of Antibiotic Gene Clusters in Streptomycetes. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chater, K.F.; Chandra, G.; Niu, G.; Tan, H. Molecular Regulation of Antibiotic Biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 112–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Ye, Z.; Feng, Z.; Wen, A.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L.; Song, Q.; Wang, F.; Liu, T.; et al. Structural insights into transcription activation of the Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein, AfsR. iScience 2024, 27, 110421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ju, K.S.; Yu, X.; Velasquez, J.E.; Mukherjee, S.; Lee, J.; Zhao, C.; Evans, B.S.; Doroghazi, J.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; et al. Use of a phosphonate methyltransferase in the identification of the fosfazinomycin biosynthetic gene cluster. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 1334–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, B. NPDC Portal. 2024. Available online: https://npdc.rc.ufl.edu/home (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Wendt-Pienkowski, E.; Shen, B. Identification and utility of FdmR1 as a Streptomyces antibiotic regulatory protein activator for fredericamycin production in Streptomyces griseus ATCC 49344 and heterologous hosts. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5587–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash: Fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, S.B.; Kanagasundaram, Y.; Fan, H.; Arumugam, P.; Eisenhaber, B.; Eisenhaber, F. The 160K Natural Organism Library, a unique resource for natural products research. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzatto-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, D.; Tan, L.L.; Heng, E. Training old dogs to do new tricks: A general multi-pronged activation approach for natural product discovery in Actinomycetes. Res. Sq. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, D.W.P.; Tan, L.L.; Heng, E.; Zulkarnain, N.; Chin, E.J.; Tan, Z.Y.Q.; Leong, C.Y.; Ng, V.W.P.; Yang, L.K.; Seow, D.C.S.; et al. Tandem mass spectral metabolic profiling of 54 actinobacterial strains and their 459 mutants. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Yu, F.; Deng, Z.; Lin, S.; Zheng, J. Structural and functional characterization of AfsR, an SARP family transcriptional activator of antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leipe, D.D.; Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. STAND, a class of P-loop NTPases including animal and plant regulators of programmed cell death: Multiple, complex domain architectures, unusual phyletic patterns, and evolution by horizontal gene transfer. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 343, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltz-2 Model by MIT. Available online: https://build.nvidia.com/mit/boltz2 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Lin, Z.; Akin, H.; Rao, R.; Hie, B.; Zhu, Z.; Lu, W.; Smetanin, N.; Verkuil, R.; Kabeli, O.; Shmueli, Y.; et al. Evolutionary-scale prediction of atomic-level protein structure with a language model. Science 2023, 379, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DIAMOND-BLASTP Outputs from NPDC Database a | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Top MiBIG Hit | BGCs (GCFs) | Main PKS Class (%) | Genomes (Mash Clusters b) | Main Species | Sequence Identity (%) to RedD | Sequence Identity (%) to Fzm_SARP |

| Fzm_SARP (WP_078621770.1) | Fosfazinomycin A | 251 (36) | T1PKS (31%) | 246 (52) | Streptomyces Kitasatospora | 33.6 | 100 |

| BafG [19] | Bafilomycin B1 | 768 (132) | T1PKS (18%) | 553 (126) | Streptomyces Kitasatospora | 30.65 | 40.61 |

| FdmR [25] | Fredericamycin A | 1043 (168) | T2PKS/butyrolactone (10%) | 870 (199) | Streptomyces Kitasatospora | 36.12 | 34.78 |

| RedD [20] | Undecylprodigiosin | 89 (5) | NRPS-like/T1PKS (84%) | 89 (8) | Streptomyces | 100 | 33.6 |

| PapR2 [20] | Fogacin A | 878 (122) | T2PKS/butyrolactone (10%) | 794 (175) | Streptomyces | 41.96 | 36.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heng, E.; Tan, L.L.; Lim, Y.W.; Koh, W.; Ng, S.B.; Lim, Y.H.; Tay, D.W.P.; Wong, F.T. Enhancing Secondary Metabolite Production in Actinobacteria Through Over-Expression of a Medium-Sized SARP Regulator. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311723

Heng E, Tan LL, Lim YW, Koh W, Ng SB, Lim YH, Tay DWP, Wong FT. Enhancing Secondary Metabolite Production in Actinobacteria Through Over-Expression of a Medium-Sized SARP Regulator. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311723

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeng, Elena, Lee Ling Tan, Yi Wee Lim, Winston Koh, Siew Bee Ng, Yee Hwee Lim, Dillon W. P. Tay, and Fong Tian Wong. 2025. "Enhancing Secondary Metabolite Production in Actinobacteria Through Over-Expression of a Medium-Sized SARP Regulator" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311723

APA StyleHeng, E., Tan, L. L., Lim, Y. W., Koh, W., Ng, S. B., Lim, Y. H., Tay, D. W. P., & Wong, F. T. (2025). Enhancing Secondary Metabolite Production in Actinobacteria Through Over-Expression of a Medium-Sized SARP Regulator. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311723