Genotoxicity Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Produced via HVAD: Examination of Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Chinchilla lanigera Blood Lymphocytes In Vitro

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

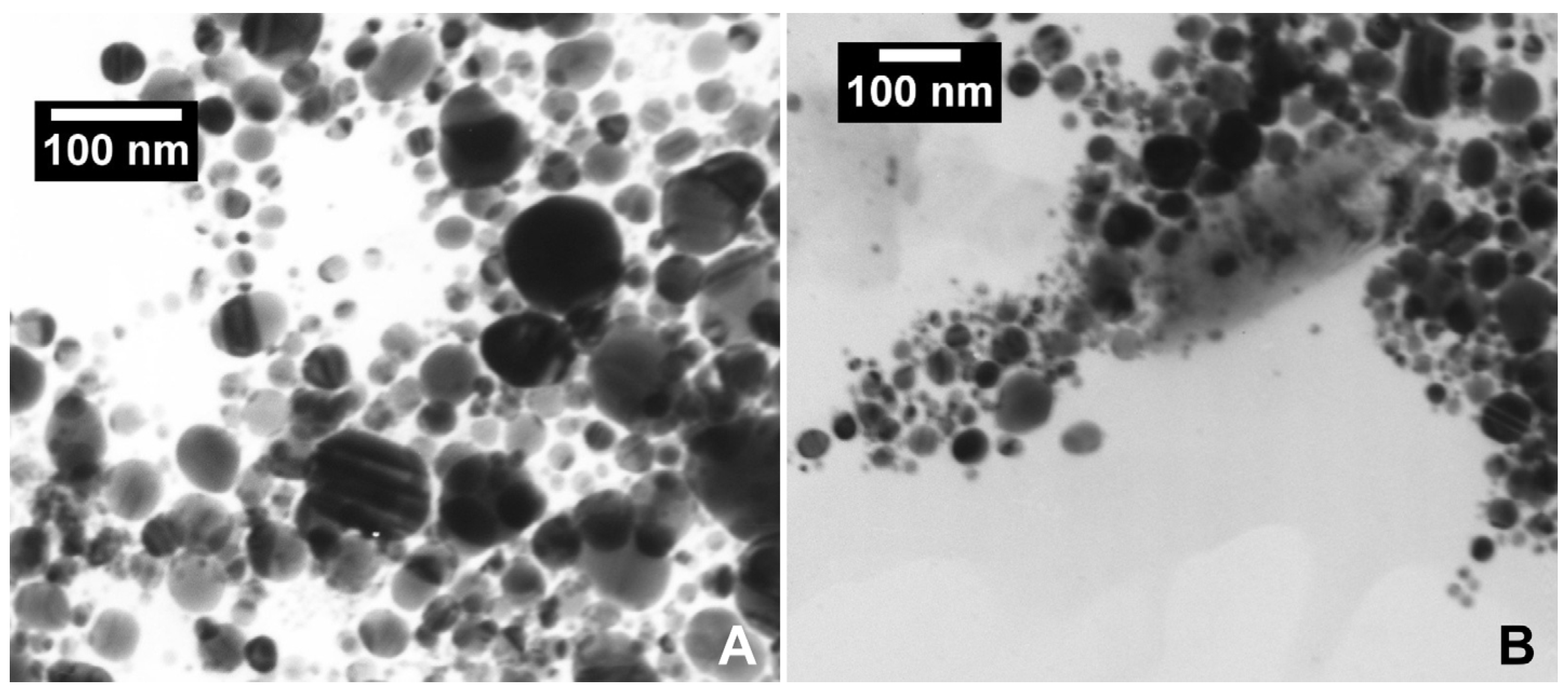

2.1. Silver Nanoparticles

2.2. Sister Chromatid Exchange

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Material—Animals

4.2. Material—Silver Nanoparticles

4.3. Methods—Cell Exposure to Silver Nanoparticles

4.4. Methods—Cell Cultures for Cytogenetic Assay

4.5. Methods—Sister Chromatid Exchange Assay

4.6. Microscopic Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dobrzyńska, M.M.; Gajowika, A.; Radzikowska, J.; Lankoff, A.; Dusinská, M.; Kruszewski, M. Genotoxicity of silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in bone marrow cells of rats in vivo. Toxicology 2014, 315, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, K.K.; Verma, R.; Awasthi, A.; Awasthi, K.; Soni, I.; John, J.P. In vivo genotoxic assessment of silver nanoparticles in liver cells of Swiss albino mice using comet assay. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2015, 6, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, L.; Zhao, J.; Skonieczna, M.; Zhou, P.-K.; Huang, R. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: Applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm 2023, 4, e327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Tikoo, K. Evaluating cell specific cytotoxicity of differentially charged silver nanoparticles. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruszewski, M.; Brzoska, K.; Brunborg, G.; Asare, N.; Dobrzyńska, M.; Dušinská, M.; Fjellsbø, L.M.; Georgantzopoulou, A.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Gutleb, A.C.; et al. Toxicity of Silver Nanomaterials in Higher Eucaryotes. Adv. Mol. Toxicol. 2011, 5, 179–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pulit-Prociak, J.; Banach, M. Silver nanoparticles—A material of the future…? Open Chem. 2016, 14, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okur, E.E.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Comprehensive Review of Silver Nanoparticles in Food Packaging Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.J.M.; Sinhaa, S.; Chakrabortyc, A.; Mallick, A.K.; Bandyopadhyaye, M.; Mukherjeea, A. In vitro and in vivo genotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2012, 749, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliga, A.R.; Skoglund, S.; Wallinder, I.O.; Fadeel, B.; Karlsson, H.L. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in human lung cells: The role of cellular uptake, agglomeration and Ag release. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Azawi, R.S.A.; Alneamah, G.A.A.; Shakir, A.J.; Shakir, A.A. In vivo: Toxicopathological and cytogenetical study of silver nanoparticles (agnps) toxicity in female rats. Biochem. Cell. Arch. 2020, 20, 171–174. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353851651_IN_VIVO_TOXICOPATHOLOGICAL_AND_CYTOGENETICAL_STUDY_OF_SILVER_NANOPARTICLES_AgNPS_TOXICITY_IN_FEMALE_RATS#fullTextFileContent (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Güzel, D.; Güneş, M.; Yalçın, B.; Akarsu, E.; Rencüzoğulları, E.; Kaya, B. Genotoxic potential of different nano-silver halides in cultured human lymphocyte cells. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 46, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świdwińska-Gajewska, A.M.; Czerczak, S. Nanocząstki ditlenku tytanu—Działanie biologiczne. Med. Pr. 2014, 65, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Yao, C.; Ding, L.; Lei, Z.; Wu, M. Techniques for Investigating Molecular Toxicology of Nanomaterials. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2016, 12, 1115–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzawa-Zegota, M.; Sharma, V.; Najafzadeh, M.; Reynolds, P.D.; Davies, J.P.; Shukla, R.K.; Dhawan, A.; Andreson, D. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Induce DNA Damage in Peripheral Blood Lymphocytes from Polyposis coli, Colon Cancer Patients and Healthy Individuals: An Ex Vivo/In Vitro Study. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 17, 9274–9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battal, D.; Celik, A.; Guler, G.; Aktas, A.; Yildirimcan, S.; Ocakoglu, K. SiO2 Nanoparticule-induced size-dependent genotoxicity—An in vitro study using sister chromatid exchange, micronucleus and comet assay. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 38, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, M.; Bidgoli, S.A.; Khoei, S.; Mahmoudzadeh, A.; Sorkhabadi, S.M.R. Cytotoxicity and genooxicity of silver nanoparticles in Chinese Hamster ovary cell line (CHO-K1) cells. Nucleus 2019, 62, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, T.; Su, X.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Gan, J.; Wu, T.; Kong, L.; Zhang, T.; Tang, M.; et al. Genotoxic effect of silver nanoparticles with/without coating in human liver HepG2 cells and in mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackenberg, S.; Scherzed, A.; Kessler, M.; Hummel, S.; Technau, A.; Froelich, K.; Ginzkey Ch Koehler Ch Hagen, R.; Kleinsasser, N. Silver nanoparticles: Evaluation of DNA damage, toxicity and functional impairment in human mesenchymal stem cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2011, 201, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magdolenova, Z.; Collins, A.; Kumar, A.; Dhawan, A.; Stone, V.; Dusinska, M. Mechanisms of genotoxicity. A review of in vitro and in vivo studies with engineered nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology 2013, 8, 233–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rija, I.S.; Lee, J.H.; Hong, S.W.; Shin, D.-M.; Lee, J.H.; Han, D.-W. A critical review on genotoxicity potential of low dimensional nanomaterials. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchta-Gładysz, M.; Wójcik, E.; Szeleszczukl, O.; Niedbała, P.; Tyblewska, K. Spontaneous sister chromatyd exchange in mitotic chromosomes of chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera). Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 95, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevino, M.; Lobarinas, E.; Maulden, A.C.; Heinz, M.G. The chinchilla animal model for hearing science and noise-induced hearing loss. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 27, 3710–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilhofer, E.M.; Hebesberger, D.V.; Waiblinger, S.; Künzel, F.; Rouha-Mülleder, C.; Mariti, C.; Windschnurer, I. Husbandry Condition and Welfare State of Pet Chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera) and Caretakers’ Perception of Stress and Emotional Closeness to their Animals. Animals 2024, 14, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchta-Gładysz, M.; Grabowska-Joachimiak, A.; Szeleszczuk, O.; Szczerbal, I.; Kociucka, B.; Niedbała, P. Karyotyping of Chinchilla lanigera Mol. (Rodentia, Chinchillidae). Caryologia 2015, 68, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchta, M.; Szeleszczuk, O.; Łysek, B. Profile of chromosome X in chinchilla (Chinchilla lanigera Mol.) karyotype. Scientifur 2008, 32, 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Manshian, B.; Jenkins, G.J.S.; Griffiths, S.M.; Williams, P.M.; Maffeis, T.G.G.; Wright, C.J.; Doak, S.H. NanoGenotoxicology: The DNA damaging potential of engineered nanomaterials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3891–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekh, K.; Ansari, R.A.; Omidi, Y.; Shakil, S.A. Chapter 2. Molecular Impacts of Advanced Nanomaterials at Genomic and Epigenomic Levels. In Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials in Genomics and Epigenomics, 1st ed.; Sahu, S.C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Asharani, P.V.; Wu, Y.L.; Gong, Z.; Valiyaveettil, S. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles in zebrafish models. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asharani, P.V.; Prakash Hande, M.; Valiyaveettil, S. Anti-proliferative activity of silver nanoparticles. BMC Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Rim, K.-T.; Kim, J.-K.; Kim, H.-Y.; Yang, J.-S. Evaluation of Genotoxic Toficity of Cyclopentane and Ammonium Nitrate—In Vitro Mammalian Chromosomal Aberration Assay in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells. Saf. Health Work 2011, 2, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.R.H. Studies on the Genotoxicity Behavior of Silver Nanoparticles in The Presence of Heavy Metal Cadmium Chloride in Mice. J. Nanomater. 2016, 3, 5283162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; Badiye, A.; Vajpayee, K.; Kapoor, N. Genotoxic Potential of Nanoparticles: Structural and Functional Modification in DNA. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 728250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecwan, M.; Das, M.; Thakore, S.; Bakshi, S.R. In-Vitro Study on Genotoxicity of Green Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2021, 13, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzesiakowska, A.; Kasprowicz, M.J.; Kuchta-Gładysz, M.; Rymuza, K.; Szeleszczuk, O. Genotoxicity of physical silver nanoparticles, produced by the HVAD method, for Chinchilla lanigera genome. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasprowicz, M.J.; Kozioł, M.; Gorczyca, A. The effect of silver nanoparticles on phytopathogenic spores of Fusarium culmorum. Can. J. Microbiol. 2010, 56, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprowicz, M.J.; Gorczyca, A.; Janas, P. Production of silver nanoparticles using High Voltage Arc Discharge method. Curr. Nanosci. 2016, 12, 747–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Berardino, D.; Jovino, V.; Lioi, B.M.; Scarfi, M.R.; Burguete, I. Spontaneous rate of sister chromatid exchange (SCEs) and BrdU dose—Response in mitotic chromosomes of goat (Capra hircus). Hereditas 1996, 124, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlman, B.A.; Kronborg, D. Sister chromatid exchanges in Vicia faba. I. Demonstration by a modified fluorescent plus Giemsa (FPG) technique. Chromosoma 1975, 51, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS. SAS/STAT 13.2 User’s Guide; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

| Number of SCEs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions | Time [h] | Concentration [μg/L] | Mean Values for the Solution | ||

| 5 | 10 | 20 | |||

| AgNP-HVAD | 3 | 5.84 ± 2.69 | 5.10 ± 3.19 | 5.84 ± 2.67 | 5.59 ± 2.85 |

| 6 | 4.84 ± 2.75 | 7.24 ± 4.22 | 5.62 ± 2.06 | 5.90 ± 3.01 | |

| 24 | 6.00 ± 2.96 | 4.36 ± 2.37 | 4.12 ± 2.52 | 4.83 ± 2.62 | |

| mean | 5.56 ± 2.73 | 5.57 ± 3.26 | 5.19 ± 2.42 | - | |

| AgNP+C | 3 | 7.32 ± 3.28 | 5.39 ± 3.68 | 4.77 ± 2.98 | 5.83 ± 3.31 |

| 6 | 5.36 ± 3.36 | 6.57 ± 2.34 | 5.71 ± 1.96 b | 5.88 ± 2.55 | |

| 24 | 6.46 ± 3.34 a | 6.02 ± 2.80 | 3.39 ± 1.13 ab | 5.29 ± 2.42 | |

| mean | 6.38 ± 3.33 | 6.00 ± 2.94 | 4.62 ± 2.02 | - | |

| AgNO3 | 3 | 6.21 ± 3.25 a | 5.54 ± 2.95 | 4.91 ± 2.07 | 5.55 ± 2.76 |

| 6 | 3.80 ± 1.75 ab | 6.21 ± 2.33 | 5.00 ± 2.18 | 5.00 ± 2.09 | |

| 24 | 5.73 ± 2.22 b | 5.40 ± 2.13 | 6.11 ± 3.27 | 5.74 ± 2.54 | |

| mean | 5.25 ± 2.41 | 5.72 ± 2.47 | 5.34 ± 2.51 | - | |

| Control | 1.57 ± 1.10 | ||||

| Terminal SCE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions | Time [h] | Concentration [μg/L] | Mean Values for the Solution | ||

| 5 | 10 | 20 | |||

| AgNP-HVAD | 3 | 3.45 ± 1.58 | 2.67 ± 2.14 | 3.40 ± 2.42 | 3.17 ± 2.05 |

| 6 | 3.02 ± 1.89 | 4.35 ± 3.17 | 3.69 ± 1.70 | 3.69 ± 2.25 | |

| 24 | 3.03 ± 1.95 | 2.46 ± 1.74 | 1.94 ± 1.78 | 2.48 ± 1.82 | |

| mean | 3.17 ± 1.81 | 3.16 ± 2.35 | 3.01 ± 1.97 | - | |

| AgNP+C | 3 | 3.94 ± 1.74 | 2.89 ± 2.18 | 3.00 ± 1.69 | 3.28 ± 1.87 |

| 6 | 3.19 ± 2.01 | 4.50 ± 1.70 | 3.18 ± 1.53 | 3.62 ± 1.75 | |

| 24 | 3.49 ± 1.56 | 3.73 ± 2.45 | 1.44 ± 1.18 | 2.89 ± 1.73 | |

| mean | 3.54 ± 1.77 | 3.71 ± 2.11 | 2.54 ±1.47 | - | |

| AgNO3 | 3 | 3.87 ± 2.17 | 2.48 ± 1.88 | 3.36 ± 1.21 | 3.24 ± 1.75 |

| 6 | 2.13 ± 1.01 | 1.89 ± 1.54 | 2.73 ± 1.16 | 2.25 ± 1.24 | |

| 24 | 3.49 ± 1.53 | 2.85 ± 1.63 | 3.15 ± 1.85 | 3.16 ± 1.67 | |

| mean | 3.16 ± 1.57 | 2.41 ± 1.68 | 3.08 ± 1.41 | - | |

| Control | 0.96 ± 0.87 | ||||

| Centromere SCE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions | Time [h] | Concentration [μg/L] | Mean Values for the Solution | ||

| 5 | 10 | 20 | |||

| AgNP-HVAD | 3 | 2.18 ± 1.78 | 2.27 ± 1.81 | 2.08 ± 1.04 | 2.18 ± 1.54 |

| 6 | 1.63 ± 1.34 | 2.80 ± 1.63 | 1.94 ± 0.68 | 2.12 ± 1.22 | |

| 24 | 2.63 ± 1.78 | 1.84 ± 1.54 | 1.88 ± 1.32 | 2.12 ± 1.55 | |

| mean | 6.44 ± 1.63 | 2.28 ± 1.66 | 1.97 ± 1.01 | - | |

| AgNP+C | 3 | 3.28 ± 2.57 | 2.46 ± 2.18 | 1.61 ± 1.56 | 2.45 ± 2.10 |

| 6 | 2.13 ± 1.89 | 2.00 ± 0.88 | 2.41 ± 1.16 | 2.18 ± 1.31 | |

| 24 | 2.79 ± 2.30 | 2.29 ± 0.93 | 1.89 ± 1.17 | 2.32 ± 1.47 | |

| mean | 2.73 ± 2.25 | 2.25 ± 1.33 | 1.97 ± 1.30 | - | |

| AgNO3 | 3 | 2.23 ± 1.73 | 2.62 ± 1.78 | 1.55 ± 1.04 | 2.13 ± 1.52 |

| 6 | 1.67 ± 1.18 | 2.33 ± 1.61 | 2.27 ± 1.45 | 2.09 ± 1.41 | |

| 24 | 2.10 ± 1.24 | 2.26 ± 1.56 | 2.82 ± 2.02 | 2.39 ± 1.61 | |

| mean | 2.00 ± 1.38 | 2.40 ± 1.65 | 2.21 ± 1.50 | - | |

| Control | 0.60 ± 0.76 | ||||

| Interstitial SCE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions | Time [h] | Concentration [μg/L] | Mean Values for the Solution | ||

| 5 | 10 | 20 | |||

| AgNP-HVAD | 3 | 0.21 ± 0.41 | 0.18 ± 0.43 | 0.24 ± 0.52 | 0.21 ± 0.45 |

| 6 | 0.22 ± 0.42 | 0.09 ± 0.29 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.10 ± 0.24 | |

| 24 | 0.28 ± 0.61 | 0.10 ± 0.30 | 0.29 ± 0.59 | 0.22 ± 0.50 | |

| mean | 0.23 ± 0.48 | 0.12 ± 0.34 | 0.18 ± 0.37 | - | |

| AgNP+C | 3 | 0.11 ± 0.31 | 0.04 ± 0.19 | 0.16 ± 0.43 | 0.10 ± 0.31 |

| 6 | 0.03 ± 0.18 | 0.07 ± 0.27 | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.07 ± 0.26 | |

| 24 | 0.18 ± 0.39 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.06 ± 0.23 | 0.08 ± 0.21 | |

| mean | 0.11 ± 0.29 | 0.04 ± 0.15 | 0.11 ± 0.33 | - | |

| AgNO3 | 3 | 0.11 ± 0.32 | 0.46 ± 0.58 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.19 ± 0.30 |

| 6 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.33 ± 0.60 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.11 ± 0.60 | |

| 24 | 0.12 ± 0.33 | 0.31 ± 0.54 | 0.15 ± 0.46 | 0.19 ± 0.44 | |

| mean | 0.08 ± 0.22 | 0.37 ± 0.41 | 0.05 ± 0.15 | - | |

| Control | 0.01 ± 0.12 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grzesiakowska-Dul, A.; Kasprowicz, M.J.; Jarnecka, O.; Kuchta-Gładysz, M. Genotoxicity Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Produced via HVAD: Examination of Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Chinchilla lanigera Blood Lymphocytes In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311703

Grzesiakowska-Dul A, Kasprowicz MJ, Jarnecka O, Kuchta-Gładysz M. Genotoxicity Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Produced via HVAD: Examination of Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Chinchilla lanigera Blood Lymphocytes In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311703

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrzesiakowska-Dul, Anna, Marek J. Kasprowicz, Olga Jarnecka, and Marta Kuchta-Gładysz. 2025. "Genotoxicity Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Produced via HVAD: Examination of Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Chinchilla lanigera Blood Lymphocytes In Vitro" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311703

APA StyleGrzesiakowska-Dul, A., Kasprowicz, M. J., Jarnecka, O., & Kuchta-Gładysz, M. (2025). Genotoxicity Assessment of Silver Nanoparticles Produced via HVAD: Examination of Sister Chromatid Exchanges in Chinchilla lanigera Blood Lymphocytes In Vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11703. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311703