Ovarian Tumor Biomarkers: Correlation Between Tumor Type and Marker Expression, and Their Role in Guiding Therapeutic Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Classification of Ovarian Tumors and Associated Biomarkers

2.1. Epithelial Carcinomas

2.2. Biomarker Class Performance by Epithelial Carcinoma Subtypes

2.3. Germ Cell Tumors

2.4. Sex Cord–Stromal Tumors

3. Novel Potential Biomarkers

3.1. MiRNAs in Ovarian Cancer

3.2. Lipid Metabolism Alterations, Metabolomic and Proteomic Biomarkers

3.3. ctDNA

3.4. Transcriptomic Biomarkers

4. Clinical Applications of Biomarkers

5. Challenges, Limitations, and Future Perspectives

- Take-home messages:

- -

- CA-125 and HE4 remain the most commonly used biomarkers in clinical practice due to their wide availability. They provide essential diagnostic, prognostic, and monitoring information, particularly when combined within the ROMA algorithm.

- -

- Modern molecular biomarkers—including miRNAs, circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), proteomics, metabolomics, and gene expression profiles—hold significant potential for the development of personalized treatment strategies.

- -

- However, their current use remains largely confined to research settings and specialized centers. The implementation of novel biomarkers into routine clinical practice is limited by high costs, lack of standardization, and restricted accessibility, underscoring the need for further validation studies prior to their widespread global adoption.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCA2 | ATP-binding Cassette Sub-family A Member 2 |

| AFP | Alpha-Fetoprotein |

| AGCT | Adult-Type Granulosa Cell Tumor |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AMH | Anti-Mullerian Hormone |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BCAT1 | Branched-Chain Aminotransferase 1 |

| BRAF | B-Raf Proto-oncogene |

| BRCA | Breast Cancer Gene |

| CA-125 | Cancer Antigen 125 |

| CA19-9 | Cancer Antigen 19-9 |

| CCOC | Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer |

| CK20 | Cytokeratin 20 |

| CK7 | Cytokeratin 7 |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| DLL1 | Delta-Like Ligand 1 |

| DOCK4 | Dedicator of Cytokinesis 4 |

| DUSP | Dual-Specificity Phosphatase |

| EOC | Endometrioid Ovarian Cancer |

| FGFR2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| FSH | Follicle-Stimulating Hormone |

| GADD45B | Growth Arrest and DNA Damage-Inducible Beta |

| GCT | Granulosa Cell Tumor |

| GPC-3 | Glypican-3 |

| HE4 | Human Epididymis Protein 4 |

| HELLQ | Helicase Q |

| HER2 | Receptor Tyrosine-Protein Kinase erbB-2 |

| HES1 | Hairy and Enhancer of Split-1 |

| HGSOC | High-Grade Serous Carcinoma |

| HNF-1β | Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 1-beta |

| HOXA9 | Homeobox A9 |

| HPF | High-Power Field |

| IFITM1 | Interferon-Induced Transmembrane Protein 1 |

| IMP3 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor 2 mRNA-Binding Protein 3 |

| JAG2 | Jagged 2 |

| Ki67 | Antigen Kiel 67 |

| KLF4 | Krüppel-Like Factor 4 |

| KRAS | Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Virus |

| KRT19 | Keratin 19 |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LGSC | Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma |

| lncRNA | Long Non-coding RNA |

| LPC | Lysophosphatidylcholine |

| MCM4 | Maintenance complex component 4 |

| MOC | Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MUC1 | Mucin-1 |

| MUC5B | Mucin 5B |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| NRAS | Neuroblastoma RAS Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| P53 | Tumor protein 53 |

| PARP | Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase |

| PAX8 | Paired Box Gene 8 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PLAP | Placental Alkaline Phosphatase |

| PPA1 | Inorganic Pyrophosphatase 1 |

| PR | Progesterone receptor |

| PUMA | p53 Upregulated Modulator of Apoptosis |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RBFOX3 | RNA Binding Fox-1 Homolog 3 |

| ROMA | Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm |

| SALL4 | Spalt-Like Transcription Factor 4 |

| SATB2 | Special AT-Rich Sequence-Binding Protein 2 |

| SF1 | Steroidogenic Factor 1 |

| SLC4A1 | Solute Carrier Family 4 Member 1 |

| SLCT | Ovarian Sertoli–Leydig Cell Tumor |

| TNXB | Tenascin-XB |

| USP9X | Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 9 |

| WFDC2 | WAP Four-Disulfide Core Domain Protein 2 |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WT1 | Wilms Tumor 1 |

| YST | Yolk Sac Tumor |

| β-hCG | Beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

References

- Kant, R.H.; Rather, S.; Rashid, S. Clinical and Histopathological Profile of Patients with Ovarian Cyst Presenting in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Kashmir, India. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 5, 2696–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.S.; Ahmed, A.G.; Mohammed, S.N.; Qadir, A.A.; Bapir, N.M.; Fatah, G.M. Benign Tumor Publication in One Year (2022): A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ 2023, 2, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saani, I.; Raj, N.; Sood, R.; Ansari, S.; Mandviwala, H.A.; Sanchez, E.; Boussios, S. Clinical Challenges in the Management of Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Cai, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Z.; Chen, Q. Prognosis and Postoperative Surveillance of Benign Ovarian Tumors in Children: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J. Pediatr. 2025, 101, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlDakhil, L.; Aljuhaimi, A.; AlKhattabi, M.; Alobaid, S.; Mattar, R.E.; Alobaid, A. Ovarian Neoplasia in Adolescence: A Retrospective Chart Review of Girls with Neoplastic Ovarian Tumors in Saudi Arabia. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Feng, H.; Gu, X. Association Between Benign Ovarian Tumors and Ovarian Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Ten Epidemiological Studies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 895618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.T.; Al-Ani, O.; Al-Ani, F. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Ovarian Cancer. Menopause Rev. 2023, 22, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, P.M.; Jordan, S.J. Global Epidemiology of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 21, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Bi, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zheng, Z.-J. Global Incidence of Ovarian Cancer According to Histologic Subtype: A Population-Based Cancer Registry Study. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2024, 10, e2300393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, Y.; Su, L.; Su, J. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Ovarian Cancer in Women Aged 45+ from 1990 to 2021 and Projections for 2050: A Systematic Analysis Based on the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Zheng, C.B.; Gao, J.N.; Ren, S.S.; Nie, G.Y.; Li, Z.Q. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Imaging Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Ovarian Tumors. Gland Surg. 2022, 11, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bast, R.C.; Lu, Z.; Han, C.Y.; Lu, K.H.; Anderson, K.S.; Drescher, C.W.; Skates, S.J. Biomarkers and Strategies for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev 2020, 29, 2504–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluz, T.; Bogaczyk, A.; Wita-Popów, B.; Habało, P.; Kluz-Barłowska, M. Giant Ovarian Tumor. Medicina 2023, 59, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Kim, T.; Han, M.R.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Lee, S.; Choi, Y.J. Ovarian Tumor Diagnosis Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and a Denoising Convolutional Autoencoder. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17024, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dundr, P.; Singh, N.; Nožičková, B.; Němejcová, K.; Bártů, M.; Stružinská, I. Primary Mucinous Ovarian Tumors vs. Ovarian Metastases from Gastrointestinal Tract, Pancreas and Biliary Tree: A Review of Current Problematics. Diagn. Pathol. 2021, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangaribuan, M.T.M.; Razali, R.R.; Darmawi, D. Diagnostic Accuracy of CA-125 Levels for Ovarian Tumor Patients with Suspected Malignancy. Indones. J. Cancer 2025, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, Z.G.; Colak, A.; Dogan, P.; Tuncer, S.; Akbiyik, F. Diagnostic Performances of CA 125, HE4, and ROMA Index in Ovarian Cancer. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2015, 36, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Liu, T.; Han, C.; Zhang, C.; Kong, W. Differential Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Ovarian Tumors with Combined Tumor and Systemic Inflammation-Related Markers. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 3192–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köbel, M.; Kang, E.Y. The Evolution of Ovarian Carcinoma Subclassification. Cancers 2022, 14, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Rand, H.; Edey, K. Nonepithelial Ovarian Cancers. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 23, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Muinao, T.; Boruah, H.P.D.; Mahindroo, N. Current Advances in Prognostic and Diagnostic Biomarkers for Solid Cancers: Detection Techniques and Future Challenges. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Cheng, X.; Peng, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, F.; Wenting, L. Visual Analysis of Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy: A Bibliometric Analysis from 2010 to 2025. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1573512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Normanno, N.; Apostolidis, K.; Wolf, A.; Al Dieri, R.; Deans, Z.; Fairley, J.; Maas, J.; Martinez, A.; Moch, H.; Nielsen, S.; et al. Access and Quality of Biomarker Testing for Precision Oncology in Europe. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 176, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ethier, J.-L.; Fuh, K.C.; Arend, R.; Konecny, G.E.; Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Odunsi, K.; Swisher, E.M.; Kohn, E.C.; Zamarin, D. State of the Biomarker Science in Ovarian Cancer: A National Cancer Institute Clinical Trials Planning Meeting Report. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2200355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, J. Pathology of Borderline and Invasive Cancers. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 41, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat, J.; D’Angelo, E.; Espinosa, I. Ovarian Carcinomas: At Least Five Different Diseases with Distinct Histological Features and Molecular Genetics. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 80, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 53, 16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, N.; Prasad, S.R.; Vikram, R.; Shanbhogue, A.K.; Huettner, P.C.; Fasih, N. Histologic, Molecular, and Cytogenetic Features of Ovarian Cancers: Implications for Diagnosis and Treatment. Radiographics 2011, 31, 625–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberto, J.M.; Chen, S.Y.; Shih, I.M.; Wang, T.H.; Wang, T.L.; Pisanic, T.R. Current and Emerging Methods for Ovarian Cancer Screening and Diagnostics: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polajžer, S.; Černe, K. Precision Medicine in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Targeted Therapies and the Challenge of Chemoresistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torre, L.A.; Trabert, B.; DeSantis, C.E.; Miller, K.D.; Samimi, G.; Runowicz, C.D.; Gaudet, M.M.; Jemal, A.; Siegel, R.L. Ovarian Cancer Statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstein, J.; Budden, T.; Goode, E.L.; Anglesio, M.S.; Talhouk, A.; Intermaggio, M.P.; Leong, H.S.; Chen, S.; Elatre, W.; Gilks, B.; et al. Prognostic Gene Expression Signature for High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1240–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowtell, D.D.; Böhm, S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Aspuria, P.J.; Bast, R.C.; Beral, V.; Berek, J.S.; Birrer, M.J.; Blagden, S.; Bookman, M.A.; et al. Rethinking Ovarian Cancer II: Reducing Mortality from High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisio, M.A.; Fu, L.; Goyeneche, A.; Gao, Z.H.; Telleria, C. High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: Basic Sciences, Clinical and Therapeutic Standpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dochez, V.; Caillon, H.; Vaucel, E.; Dimet, J.; Winer, N.; Ducarme, G. Biomarkers and Algorithms for Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer: CA125, HE4, RMI and ROMA, a Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.; McCann, L.; Makker, S.; Mukherjee, U.; Gullapalli, S.V.N.; Erekkath, J.; Shih, S.; Mahajan, I.; Sanchez, E.; Uccello, M.; et al. Diagnostic Biomarkers in Ovarian Cancer: Advances beyond CA125 and HE4. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2024, 16, 17588359241233225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Cai, P.; Huang, Y. Clinical Analysis of Four Serum Tumor Markers in 458 Patients with Ovarian Tumors: Diagnostic Value of the Combined Use of HE4, CA125, CA19-9, and CEA in Ovarian Tumors. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.G.; McMeekin, D.S.; Brown, A.K.; DiSilvestro, P.; Miller, M.C.; Allard, W.J.; Gajewski, W.; Kurman, R.; Bast, R.C.; Skates, S.J. A Novel Multiple Marker Bioassay Utilizing HE4 and CA125 for the Prediction of Ovarian Cancer in Patients with a Pelvic Mass. Gynecol. Oncol. 2009, 112, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, A.J.; Dwight, T.; Gill, A.J.; Dickson, K.A.; Zhu, Y.; Clarkson, A.; Gard, G.B.; Maidens, J.; Valmadre, S.; Clifton-Bligh, R.; et al. Assessing Mutant P53 in Primary High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Using Immunohistochemistry and Massively Parallel Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischof, K.; Knappskog, S.; Hjelle, S.M.; Stefansson, I.; Woie, K.; Salvesen, H.B.; Gjertsen, B.T.; Bjorge, L. Influence of P53 Isoform Expression on Survival in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancers. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, S.K.; Martinez, J.D. The Significance of P53 Isoform Expression in Serous Ovarian Cancer. Future Oncol. 2012, 8, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstetter, G.; Berger, A.; Schuster, E.; Wolf, A.; Hager, G.; Vergote, I.; Cadron, I.; Sehouli, J.; Braicu, E.I.; Mahner, S.; et al. Δ133p53 Is an Independent Prognostic Marker in P53 Mutant Advanced Serous Ovarian Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2011, 105, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaker, N.; Chen, W.; Sinclair, W.; Parwani, A.V.; Li, Z. Identifying SOX17 as a Sensitive and Specific Marker for Ovarian and Endometrial Carcinomas. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Qian, L.; Deng, S.; Liu, L.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, Y. A Review of the Clinical Characteristics and Novel Molecular Subtypes of Endometrioid Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 668151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nonneville, A.; Kalbacher, E.; Cannone, F.; Guille, A.; Adelaïde, J.; Finetti, P.; Cappiello, M.; Lambaudie, E.; Ettore, G.; Charafe, E.; et al. Endometrioid Ovarian Carcinoma Landscape: Pathological and Molecular Characterization. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 2586–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard-Fortier, G.; Panzarella, T.; Rosen, B.; Chapman, W.; Gien, L.T. Endometrioid Carcinoma of the Ovary: Outcomes Compared to Serous Carcinoma After 10 Years of Follow-Up. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, R.T.; Trewin-Nybråten, C.B.; Paulsen, T.; Langseth, H. Characterization of Ovarian Cancer Survival by Histotype and Stage: A Nationwide Study in Norway. Int. J. Cancer 2023, 153, 969–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Hu, W. CA125 and HE4: Measurement Tools for Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2016, 81, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.R.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, Q. The Clinical Significance of the Combined Detection of Serum Smac, HE4 and CA125 in Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 21, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.K.; Teoh, D.; Hu, J.M.; Shin, J.Y.; Osann, K.; Kapp, D.S. Do Clear Cell Ovarian Carcinomas Have Poorer Prognosis Compared to Other Epithelial Cell Types? A Study of 1411 Clear Cell Ovarian Cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 109, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Zhu, J.; Qian, L.; Liu, H.; Shen, Z.; Wu, D.; Zhao, W.; Xiao, W.; Zhou, Y. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, Y.; Okamoto, A.; Hollis, R.L.; Gourley, C.; Herrington, C.S. Clear Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary: A Clinical and Molecular Perspective. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarfone, G.; Bergamini, A.; Noli, S.; Villa, A.; Cipriani, S.; Taccagni, G.; Vigano’, P.; Candiani, M.; Parazzini, F.; Mangili, G. Characteristics of Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer Arising from Endometriosis: A Two Center Cohort Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermsirisakpong, W.; Tuipae, S. Survival Outcomes Between Clear Cell and Non-Clear Cell Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Thai J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 21, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.W.; Bae, J.; Ha, J.; Jung, K.W. Conditional Relative Survival of Ovarian Cancer: A Korean National Cancer Registry Study. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 639839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.; Saulat, O.; Guinn, B.A. Identification of Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Targets for Therapy in Patients with Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Carcinogenesis 2022, 43, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.F.; Shen, M.R.; Huang, Y.F.; Cheng, Y.M.; Lin, S.H.; Chow, N.H.; Cheng, S.W.; Chou, C.Y.; Ho, C.L. Overexpression of the RNA-Binding Proteins Lin28B and IGF2BP3 (IMP3) Is Associated with Chemoresistance and Poor Disease Outcome in Ovarian Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Nagasaka, T.; Naiki-Ito, A.; Sato, S.; Suzuki, S.; Toyokuni, S.; Ito, M.; Takahashi, S. Napsin A Is a Specific Marker for Ovarian Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, T.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kondoh, H.; Amano, Y.; Baba, T.; Hamanishi, J.; Abiko, K.; Kosaka, K.; et al. Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-1β (HNF-1β) Promotes Glucose Uptake and Glycolytic Activity in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Carcinog. 2015, 54, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Naggar, A.M.; Li, Y.; Turgu, B.; Ding, Y.; Wei, L.; Chen, S.Y.; Trigo-Gonzalez, G.; Kalantari, F.; Vallejos, R.; Lynch, B.; et al. Cystathionine Gamma-lyase-mediated Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1-alpha Expression Drives Clear Cell Ovarian Cancer Progression. J. Pathol. 2025, 266, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.H.; Sung, H.Y.; Choi, E.N.; Lyu, D.; Choi, H.J.; Ju, W.; Ahn, J.H. Aberrant DNA Methylation in the IFITM1 Promoter Enhances the Metastatic Phenotype in an Intraperitoneal Xenograft Model of Human Ovarian Cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, L.; Gong, T.; Jiang, W.; Qian, L.; Gong, W.; Sun, Y.; Cai, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, F.; Wang, H.; et al. Proteomic Profiling of Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinomas Identifies Prognostic Biomarkers for Chemotherapy. Proteomics 2024, 24, e2300242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perren, T.J. Mucinous Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, J.; Marko, K.I.; Pachigolla, S.L.; Crothers, B.A.; Mattu, R.; Wolfman, D.J. Mucinous Neoplasms of the Ovary: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics 2019, 39, 982–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, R.L.; Stillie, L.J.; Hopkins, S.; Bartos, C.; Churchman, M.; Rye, T.; Nussey, F.; Fegan, S.; Nirsimloo, R.; Inman, G.J.; et al. Clinicopathological Determinants of Recurrence Risk and Survival in Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yu, J.; Zhang, S.; Shan, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. A Prognostic Model of Patients with Ovarian Mucinous Adenocarcinoma: A Population-Based Analysis. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, S.D.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Müller, V.; Wölber, L.; Witzel, I.; Paluchowski, P.; von Leffern, I.; Heilenkötter, U.; Jacobsen, F.; Bernreuther, C.; et al. MUC5AC Expression Is Linked to Mucinous/Endometroid Subtype, Absence of Nodal Metastasis and Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Ovarian Cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2021, 224, 153533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelariu-Raicu, A.; Holley, E.; Mayr, D.; Klauschen, F.; Wehweck, F.; Rottmann, M.; Kessler, M.; Kaltofen, T.; Czogalla, B.; Trillsch, F.; et al. A Combination of Immunohistochemical Markers, MUC1, MUC5AC, PAX8 and Growth Pattern for Characterization of Mucinous Neoplasm of the Ovary. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meagher, N.S.; Wang, L.; Rambau, P.F.; Intermaggio, M.P.; Huntsman, D.G.; Wilkens, L.R.; El-Bahrawy, M.A.; Ness, R.B.; Odunsi, K.; Steed, H.; et al. A Combination of the Immunohistochemical Markers CK7 and SATB2 Is Highly Sensitive and Specific for Distinguishing Primary Ovarian Mucinous Tumors from Colorectal and Appendiceal Metastases. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 1834–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, S.; Wasserman, J.K.; Giassi, A.; Djordjevic, B.; Parra-Herran, C. Immunohistochemistry in the Diagnosis of Mucinous Neoplasms Involving the Ovary: The Added Value of SATB2 and Biomarker Discovery Through Protein Expression Database Mining. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2016, 35, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaoud, N.; Erashdi, M.; Alkhatib, S.; Abdo, N.; Al-Mohtaseb, A.; Graboski-Bauer, A. The Utility of PAX8 and SATB2 Immunohistochemical Stains in Distinguishing Ovarian Mucinous Neoplasms from Colonic and Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner Rönnerman, E.; Pettersson, D.; Nemes, S.; Dahm-Kähler, P.; Kovács, A.; Karlsson, P.; Parris, T.Z.; Helou, K. Trefoil Factor Family Proteins as Potential Diagnostic Markers for Mucinous Invasive Ovarian Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1112152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorringe, K.L.; Cheasley, D.; Wakefield, M.J.; Ryland, G.L.; Allan, P.E.; Alsop, K.; Amarasinghe, K.C.; Ananda, S.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; Christie, M.; et al. Therapeutic Options for Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dundr, P.; Bártů, M.; Bosse, T.; Bui, Q.H.; Cibula, D.; Drozenová, J.; Fabian, P.; Fadare, O.; Hausnerová, J.; Hojný, J.; et al. Primary Mucinous Tumors of the Ovary: An Interobserver Reproducibility and Detailed Molecular Study Reveals Significant Overlap Between Diagnostic Categories. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.L.; Lee, M.Y.; Chao, W.R.; Han, C.P. The Status of Her2 Amplification and Kras Mutations in Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma. Hum. Genom. 2016, 10, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglesio, M.S.; Kommoss, S.; Tolcher, M.C.; Clarke, B.; Galletta, L.; Porter, H.; Damaraju, S.; Fereday, S.; Winterhoff, B.J.; Kalloger, S.E.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Mucinous Ovarian Tumours Supports a Stratified Treatment Approach with HER2 Targeting in 19% of Carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2013, 229, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

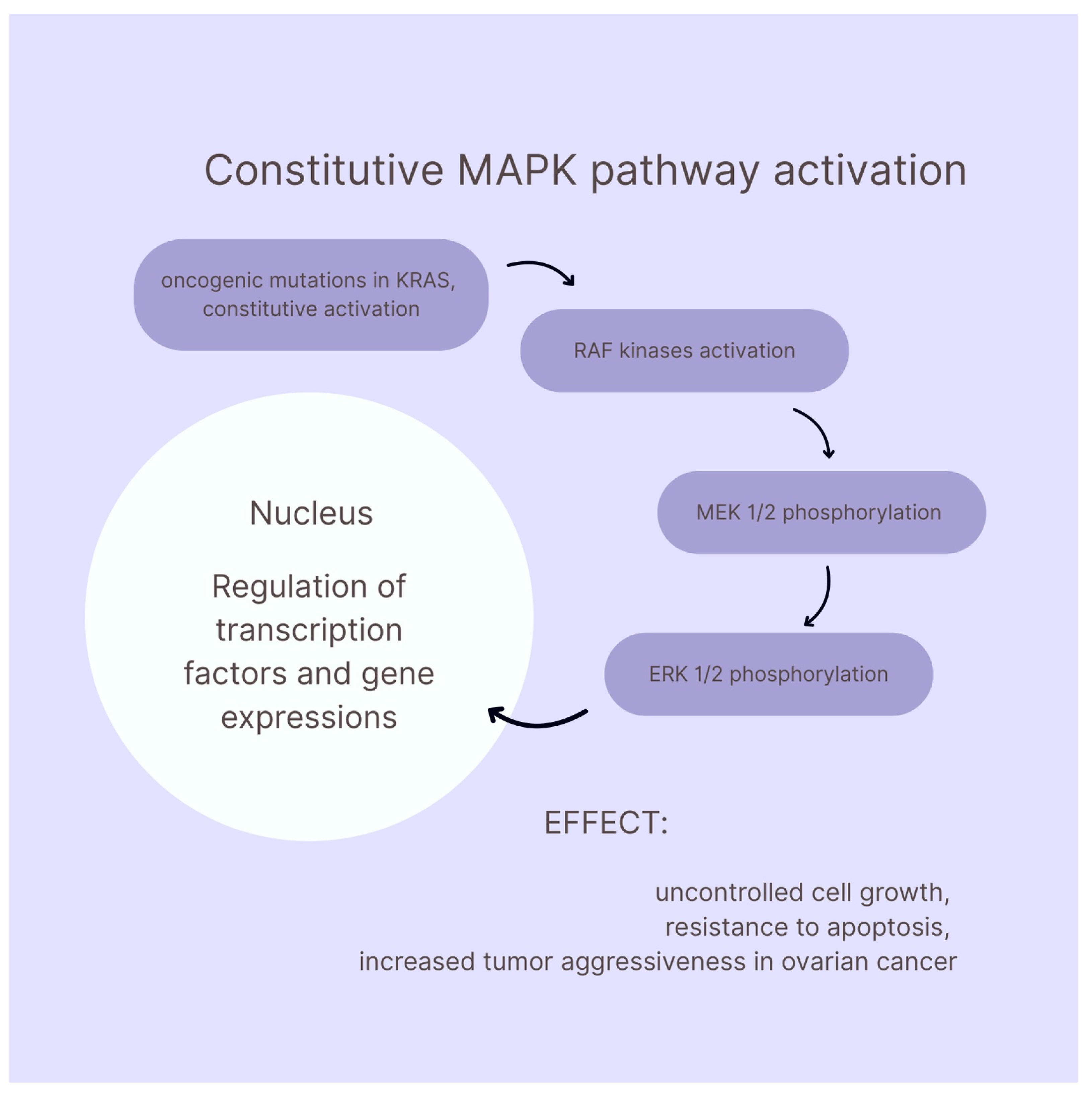

- Hendrikse, C.; Theelen, P.; van der Ploeg, P.; Westgeest, H.; Boere, I.; Thijs, A.; Ottevanger, P.; van de Stolpe, A.; Lambrechts, S.; Bekkers, R.; et al. The Potential of RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK (MAPK) Signaling Pathway Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 171, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Therachiyil, L.; Anand, A.; Azmi, A.; Bhat, A.; Korashy, H.M. Role of RAS Signaling in Ovarian Cancer. F1000Research 2022, 11, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning-Geist, B.; Gordhandas, S.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Mandelker, D.; Roche, K.L.; Zivanovic, O.; Maio, A.; et al. MAPK Pathway Genetic Alterations Are Associated with Prolonged Overall Survival in Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4456–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryland, G.L.; Hunter, S.M.; Doyle, M.A.; Caramia, F.; Li, J.; Rowley, S.M.; Christie, M.; Allan, P.E.; Stephens, A.N.; Bowtell, D.D.L.; et al. Mutational Landscape of Mucinous Ovarian Carcinoma and Its Neoplastic Precursors. Genome Med. 2015, 7, 87, Erratum in Genome Med. 2017, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J.J.; Schlappe, B.A.; Kumar, R.; Olvera, N.; Dao, F.; Abu-Rustum, N.; Aghajanian, C.; DeLair, D.; Hussein, Y.R.; Soslow, R.A.; et al. Massively Parallel Sequencing Analysis of Mucinous Ovarian Carcinomas: Genomic Profiling and Differential Diagnoses. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldawy, A.; Segev, Y.; Lavie, O.; Auslender, R.; Sopik, V.; Narod, S.A. Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 143, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaier, A.; Mal, H.; Alselwi, W.; Ghatage, P. Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma of the Ovary: The Current Status. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadducci, A.; Cosio, S. Therapeutic Approach to Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma: State of Art and Perspectives of Clinical Research. Cancers 2020, 12, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Decker, K.; Wenzel, H.H.B.; Bart, J.; van der Aa, M.A.; Kruitwagen, R.F.P.M.; Nijman, H.W.; Kruse, A.J. Stage, Treatment and Survival of Low-grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma in the Netherlands: A Nationwide Study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T.; Bernardini, M.; Lheureux, S.; Aben, K.K.H.; Bandera, E.V.; Beckmann, M.W.; Benitez, J.; Berchuck, A.; Bjørge, L.; Carney, M.E.; et al. Clinical Parameters Affecting Survival Outcomes in Patients with Low-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma: An International Multicentre Analysis. Can. J. Surg. 2023, 66, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheasley, D.; Nigam, A.; Zethoven, M.; Hunter, S.; Etemadmoghadam, D.; Semple, T.; Allan, P.; Carey, M.S.; Fernandez, M.L.; Dawson, A.; et al. Genomic Analysis of Low-grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma to Identify Key Drivers and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. J. Pathol. 2021, 253, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, J.P.; Hollis, R.L.; van Baal, J.; Ilenkovan, N.; Churchman, M.; van de Vijver, K.; Dijk, F.; Meynert, A.M.; Bartos, C.; Rye, T.; et al. Whole Exome Sequencing of Low Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma Identifies Genomic Events Associated with Clinical Outcome. Gynecol. Oncol. 2023, 174, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stružinská, I.; Hájková, N.; Hojný, J.; Krkavcová, E.; Michálková, R.; Bui, Q.H.; Matěj, R.; Laco, J.; Drozenová, J.; Fabian, P.; et al. Somatic Genomic and Transcriptomic Characterization of Primary Ovarian Serous Borderline Tumors and Low-Grade Serous Carcinomas. J. Mol. Diagn. 2024, 26, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollis, R.L.; Thomson, J.P.; van Baal, J.; Ilenkovan, N.; Churchman, M.; van de Vijver, K.; Dijk, F.; Meynert, A.M.; Bartos, C.; Rye, T.; et al. Distinct Histopathological Features Are Associated with Molecular Subtypes and Outcome in Low Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Němejcová, K.; Šafanda, A.; Bártů, M.K.; Michálková, R.; Drozenová, J.; Fabian, P.; Hausnerová, J.; Laco, J.; Matěj, R.; Méhes, G.; et al. A Comprehensive Immunohistochemical Analysis of 26 Markers in 250 Cases of Serous Ovarian Tumors. Diagn. Pathol. 2023, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisham, R.N.; Manning-Geist, B.L.; Chui, M.H. Beyond the Estrogen Receptor: In Search of Predictive Biomarkers for Low-grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 1305–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallum; Andrade, L.; Ramalho, S.; Ferracini, A.C.; Natal, R.d.A.; Carvalho Brito, A.B.; Sarian, L.O.; Derchain, S. WT1, P53 and P16 Expression in the Diagnosis of Low- and High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinomas and Their Relation to Prognosis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 15818–15827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Bellone, S.; Siegel, E.R.; Altwerger, G.; Menderes, G.; Bonazzoli, E.; Egawa-Takata, T.; Pettinella, F.; Bianchi, A.; Riccio, F.; et al. A Novel Multiple Biomarker Panel for the Early Detection of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 149, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muinao, T.; Deka Boruah, H.P.; Pal, M. Multi-Biomarker Panel Signature as the Key to Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Będkowska, G.E.; Ławicki, S.; Gacuta, E.; Pawłowski, P.; Szmitkowski, M. M-CSF in a New Biomarker Panel with HE4 and CA 125 in the Diagnostics of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients. J. Ovarian Res. 2015, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsas, A.; Stefanoudakis, D.; Troupis, T.; Kontzoglou, K.; Eleftheriades, M.; Christopoulos, P.; Panoskaltsis, T.; Stamoula, E.; Iliopoulos, D.C. Tumor Markers and Their Diagnostic Significance in Ovarian Cancer. Life 2023, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieters-Castator, D.Z.; Rambau, P.F.; Kelemen, L.E.; Siegers, G.M.; Lajoie, G.A.; Postovit, L.M.; Kobel, M. Proteomics-Derived Biomarker Panel Improves Diagnostic Precision to Classify Endometrioid and High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4309–4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.I.; Jung, M.; Dan, K.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.; Kim, H.S.; Chung, H.H.; Kim, J.W.; Park, N.H.; Song, Y.S.; et al. Proteomic Discovery of Biomarkers to Predict Prognosis of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, S.; Alli-Shaik, A.; Gunaratne, J. Machine Learning-Enhanced Extraction of Biomarkers for High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer from Proteomics Data. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Joung, J.G.; Park, H.; Choi, M.C.; Koh, D.; Jeong, J.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.Y.; Jung, D.; Hwang, S.; et al. Identification of Prognostic Biomarkers of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma: A Preliminary Study Using Spatial Transcriptome Analysis and Multispectral Imaging. Cells 2025, 14, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, C.A.; Gale, D.; Piskorz, A.M.; Biggs, H.; Hodgkin, C.; Addley, H.; Freeman, S.; Moyle, P.; Sala, E.; Sayal, K.; et al. Exploratory Analysis of TP53 Mutations in Circulating Tumour DNA as Biomarkers of Treatment Response for Patients with Relapsed High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, J.S.; Gard, G.B.; Yang, J.; Maidens, J.; Valmadre, S.; Soon, P.S.; Marsh, D.J. Combining Serum MicroRNA and CA-125 as Prognostic Indicators of Preoperative Surgical Outcome in Women with High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, J.E.; Choi, E.K. Prospective Study of the Efficacy and Utility of TP53 Mutations in Circulating Tumor DNA as a Non-Invasive Biomarker of Treatment Response Monitoring in Patients with High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 30, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.; Berezhnoy, G.; Koch, A.; Cannet, C.; Schäfer, H.; Kommoss, S.; Brucker, S.; Beziere, N.; Trautwein, C. Stratification of Ovarian Cancer Borderline from High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Patients by Quantitative Serum NMR Spectroscopy of Metabolites, Lipoproteins, and Inflammatory Markers. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1158330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Jones, L. Ovary: Germ Cell Tumors. Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 2011, 7, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshal Toppo, S.; Santram Chavan, S. Study of 92 Cases of Ovarian Germ Cell Tumour at Tertiary Health Care Centre. Indian J. Pathol. Oncol. 2019, 6, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, F.; Amant, F.; Chiappa, V.; Paolini, B.; Bergamini, A.; Fruscio, R.; Corso, G.; Raspagliesi, F.; Bogani, G. Malignant Germ Cells Tumor of the Ovary. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 36, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euscher, E.D. Germ Cell Tumors of the Female Genital Tract. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019, 12, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Wang, S.; Yeung, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.S.; Chung, J.P.W.; Chan, D.Y.L. Mature Cystic Teratoma: An Integrated Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outwater, E.K.; Siegelman, E.S.; Hunt, J.L. Ovarian Teratomas: Tumor Types and Imaging Characteristics. Radiographics 2001, 21, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Bhosale, P.; Menias, C.O.; Ramalingam, P.; Jensen, C.; Iyer, R.; Ganeshan, D. Ovarian Teratomas: Clinical Features, Imaging Findings and Management. Abdom. Radiol. 2021, 46, 2293–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, P.; Vallecillo, M.; Urga, M.; Kim, H.; Napoli, M.; Wernicke, A.; Chacon, C.; Nicola, R. Ovarian Teratomas: A Spectrum of Disease. An Approximation for Radiologists in Training. Med. Res. Arch. 2022, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Yin, M.; Cao, D.; Xiang, Y.; Yang, J. Prognostic Factors for Pure Ovarian Immature Teratoma and the Role of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage I Diseases. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2273984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.K.; Gardner, A.B.; Chan, J.E.; Guan, A.; Alshak, M.; Kapp, D.S. The Influence of Age and Other Prognostic Factors Associated with Survival of Ovarian Immature Teratoma—A Study of 1307 Patients. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 446–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, S.; Jones, N.L.; Chen, L.; Hou, J.Y.; Tergas, A.I.; Burke, W.M.; Ananth, C.V.; Neugut, A.I.; Herhshman, D.L.; Wright, J.D. Characteristics, Treatment and Outcomes of Women with Immature Ovarian Teratoma, 1998–2012. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 142, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abouelnazar, F.A.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Yu, D.; Zang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, Q.; et al. The New Advance of SALL4 in Cancer: Function, Regulation, and Implication. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2023, 37, e24927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miettinen, M.; Wang, Z.; Mccue, P.A.; Sarlomo-Rikala, M.; Rys, J.; Biernat, W.; Lasota, J.; Lee, Y.S. SALL4 Expression in Germ Cell and Non–Germ Cell Tumors: A Systematic Immunohistochemical Study of 3215 Cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Xu, L.; Bi, W.; Ou, W. Bin SALL4 Oncogenic Function in Cancers: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Relevance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, X.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; et al. Maternal Sall4 Is Indispensable for Epigenetic Maturation of Mouse Oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.L.; La, H.M.; Legrand, J.M.D.; Mäkelä, J.A.; Eichenlaub, M.; De Seram, M.; Ramialison, M.; Hobbs, R.M. Germline Stem Cell Activity Is Sustained by SALL4-Dependent Silencing of Distinct Tumor Suppressor Genes. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 9, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bîcă, O.; Ciongradi, C.I.; Benchia, D.; Sârbu, I.; Alecsa, M.; Cristofor, A.E.; Bîcă, D.E.; Lozneanu, L. Assessment of Molecular Markers in Pediatric Ovarian Tumors: Romanian Single-Center Experience. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Guo, S.; Allan, R.W.; Molberg, K.H.; Peng, Y. SALL4 Is a Novel Sensitive and Specific Marker of Ovarian Primitive Germ Cell Tumors and Is Particularly Useful in Distinguishing Yolk Sac Tumor From Clear Cell Carcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; Ali, A.; Younis, F.M. Ovarian Dysgerminoma. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2022, 32, 1490–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Sun, F.; Bao, L.; Chu, C.; Li, H.; Yin, Q.; Guan, W.; Wang, D. Pure Dysgerminoma of the Ovary: CT and MRI Features with Pathological Correlation in 13 Tumors. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Xia, C.; Krailo, M.; Amatruda, J.F.; Arul, S.G.; Billmire, D.F.; Brady, W.E.; Covens, A.; Gershenson, D.M.; Hale, J.P.; et al. Is Carboplatin-Based Chemotherapy as Effective as Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy in the Treatment of Advanced-Stage Dysgerminoma in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults? Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 150, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.A.; Park, H.J.; Park, B.K.; Lim, M.C.; Park, S.Y.; Won, Y.J. Incidence and Outcomes of Malignant Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors in Korea, 1999–2017. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 163, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Sun, F.; Li, Y. Long-Term Outcomes and Factors Related to the Prognosis of Pure Ovarian Dysgerminoma: A Retrospective Study of 107 Cases. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2022, 86, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Konishi, I.; Suzuki, A.; Okamura, H.; Okazaki, T.; Mori, T. Analysis of Serum Lactic Dehydrogenase Levels and Its Isoenzymes in Ovarian Dysgerminoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 1985, 22, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pode, D.; Kopolovic, S.; Gimmon, Z. Serum Lactic Dehydrogenase: A Tumor Marker of Ovarian Dysgerminoma in a Female Pseudohermaphrodite. Gynecol. Oncol. 1984, 19, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amante, S.; Félix, A.; Cunha, T.M.; Amante, S.; Félix, A.; Cunha, T.M. Ovarian Dysgerminoma: Clues to the Radiological Diagnosis. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 29, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Thomas, A.; Roth, L.M.; Zheng, W.; Michael, H.; Karim, F.W.A. OCT4: A Novel Biomarker for Dysgerminoma of the Ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004, 28, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehans, G.A.; Manivel, J.C.; Copland, G.T.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Wick, M.R. Immunohistochemistry of Germ Cell and Trophoblastic Neoplasms. Cancer 1988, 62, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, R.B.; Bianchi, M.V.; Ribeiro, P.R.; Argenta, F.F.; Vielmo, A.; de Sousa, F.A.B.; Piva, M.M.; Pohl, C.B.; Daoualibi, Y.; Cony, F.G.; et al. Comparison of Immunohistochemical Profiles of Ovarian Germ Cells in Dysgerminomas of a Captive Maned Wolf and Domestic Dogs. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2021, 33, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.-Y.; Xu, Y.-H. Clinicopathological Significance of Plap, NSE and WT1 Detection in Ovarian Dysgerminoma. CJCR 2003, 15, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, M.R.; Swanson, P.E.; Manivel, J.C. Placental-like Alkaline Phosphatase Reactivity in Human Tumors: An Immunohistochemical Study of 520 Cases. Hum. Pathol. 1987, 18, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Aihara, Y.; Kikuno, A.; Sato, T.; Komoda, T.; Kubo, O.; Amano, K.; Okada, Y.; Koyamaishi, Y. A Highly Sensitive and Specific Chemiluminescent Enzyme Immunoassay for Placental Alkaline Phosphatase in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Intracranial Germinomas. Pediatr. Neurosurg. 2013, 48, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbatoghli, M.; Shamshiripour, P.; Fattahi, F.; Kalantari, E.; Habibi Shams, Z.; Panahi, M.; Totonchi, M.; Asadi-Lari, Z.; Madjd, Z.; Saeednejad Zanjani, L. Co-Expression of Cancer Stem Cell Markers, SALL4/ALDH1A1, Is Associated with Tumor Aggressiveness and Poor Survival in Patients with Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. J. Ovarian Res. 2022, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.H.; Wong, A.; Stall, J.N. Yolk Sac Tumor of the Ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2022, 46, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasioudis, D.; Mastroyannis, S.A.; Haggerty, A.F.; Ko, E.M.; Latif, N.A. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig and Granulosa Cell Tumor: Comparison of Epidemiology and Survival Outcomes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyraz, G.; Durmus, Y.; Cicin, I.; Kuru, O.; Bostanci, E.; Comert, G.K.; Sahin, H.; Ayik, H.; Ureyen, I.; Karalok, A.; et al. Prognostic Factors and Oncological Outcomes of Ovarian Yolk Sac Tumors: A Retrospective Multicentric Analysis of 99 Cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2019, 300, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawa, A.; Obata, N.; Kikkawa, F.; Kawai, M.; Nagasaka, T.; Goto, S.; Nishimori, K.; Nakashima, N. Prognostic Factors of Patients with Yolk Sac Tumors of the Ovary. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 184, 1182–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.-L.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Zhu, J.-Q. Prognostic Value of Serum α-Fetoprotein in Ovarian Yolk Sac Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 3, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dällenbach, P.; Bonnefoi, H.; Pelte, M.F.; Vlastos, G. Yolk Sac Tumours of the Ovary: An Update. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2006, 32, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Wu, Z.; Hu, C.; Xie, W.; He, J.; Liu, H.; Cao, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Gong, W. Alpha Fetoprotein (AFP)-Producing Gastric Cancer: Clinicopathological Features and Treatment Strategies. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lin, B.; Li, M. The Role of Alpha-Fetoprotein in the Tumor Microenvironment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1363695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Li, M. Inhibition of Autophagy and Immune Response: Alpha-Fetoprotein Stimulates Initiation of Liver Cancer. J. Cancer Immunol. 2020, 2, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teilum, G.; Albrechtsen, R.; Nørgaard-Pedersen, B. The histogenetic-embryologic basis for reappearance of alpha-fetoprotein in endodermal sinus tumors (yolk sac tumors) and teratomas. APMIS 1975, 83A, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, Y.H.; Lee, Y.-T.; Tseng, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; You, S.; Agopian, V.G.; Yang, J.D. Alpha-Fetoprotein: Past, Present, and Future. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Fankhauser, C.; Hermanns, T.; Beyer, J.; Christiansen, A.; Moch, H.; Bode, P.K. HNF1β Is a Sensitive and Specific Novel Marker for Yolk Sac Tumor: A Tissue Microarray Analysis of 601 Testicular Germ Cell Tumors. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, P.; Malpica, A.; Silva, E.G.; Gershenson, D.M.; Liu, J.L.; Deavers, M.T. The Use of Cytokeratin 7 and EMA in Differentiating Ovarian Yolk Sac Tumors From Endometrioid and Clear Cell Carcinomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2004, 28, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadare, O.; Shaker, N.; Alghamdi, A.; Ganesan, R.; Hanley, K.Z.; Hoang, L.N.; Hecht, J.L.; Ip, P.P.; Shaker, N.; Roma, A.A.; et al. Endometrial Tumors with Yolk Sac Tumor-like Morphologic Patterns or Immunophenotypes: An Expanded Appraisal. Mod. Pathol. 2019, 32, 1847–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esheba, G.E.; Pate, L.L.; Longacre, T.A. Oncofetal Protein Glypican-3 Distinguishes Yolk Sac Tumor From Clear Cell Carcinoma of the Ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008, 32, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zynger, D.L.; Everton, M.J.; Dimov, N.D.; Chou, P.M.; Yang, X.J. Expression of Glypican 3 in Ovarian and Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumors. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2008, 130, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zynger, D.L.; McCallum, J.C.; Luan, C.; Chou, P.M.; Yang, X.J. Glypican 3 Has a Higher Sensitivity than Alpha-fetoprotein for Testicular and Ovarian Yolk Sac Tumour: Immunohistochemical Investigation with Analysis of Histological Growth Patterns. Histopathology 2010, 56, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, D.; Ota, S.; Takazawa, Y.; Aburatani, H.; Nakagawa, S.; Yano, T.; Taketani, Y.; Kodama, T.; Fukayama, M. Glypican-3 Expression in Clear Cell Adenocarcinoma of the Ovary. Mod. Pathol. 2009, 22, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rougemont, A.L.; Tille, J.C. Role of HNF1β in the Differential Diagnosis of Yolk Sac Tumor from Other Germ Cell Tumors. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 81, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, A.; Peng, Y.; Rakheja, D.; Wei, L.; Xue, D.; Allan, R.W.; Molberg, K.H.; Li, J.; Cao, D. Diagnostic Utility of SALL4 in Extragonadal Yolk Sac Tumors: An Immunohistochemical Study of 59 Cases With Comparison to Placental-like Alkaline Phosphatase, Alpha-Fetoprotein, and Glypican-3. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 1529–1539, Erratum in Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Luo, R.; Sun, B.; Zhao, J.; Xu, Q.; Feng, S.; Chen, X.; Wang, C. SALL4 Is a Useful Marker for Pediatric Yolk Sac Tumors. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2020, 36, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Pang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, P. Clinicopathological Factors and Prognosis Analysis of 39 Cases of Non-Gestational Ovarian Choriocarcinoma. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 301, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishino, K.; Yamamoto, E.; Ikeda, Y.; Niimi, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Kajiyama, H. A Poor Prognostic Metastatic Nongestational Choriocarcinoma of the Ovary: A Case Report and the Literature Review. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H.O.; Qualls, C.R.; Prairie, B.A.; Padilla, L.A.; Rayburn, W.F.; Key, C.R. Trends in Gestational Choriocarcinoma: A 27-Year Perspective. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Pan, B.; Wan, X.; Yang, J.; Feng, F.; Ren, T.; Zhao, J. Clinical Features of a Chinese Female Nongestational Choriocarcinoma Cohort: A Retrospective Study of 37 Patients. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serno, J.; Zeppernick, F.; Jäkel, J.; Schrading, S.; Maass, N.; Meinhold-Heerlein, I.; Bauerschlag, D.O. Primary Pulmonary Choriocarcinoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2012, 74, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenache, D.G. Current Practices When Reporting Quantitative Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Test Results. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020, 5, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Du, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y. Pure Primary Non-Gestational Choriocarcinoma Originating in the Ovary: A Case Report and Literature Review. Rare Tumors 2021, 13, 20363613211052506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, P.; Shivam, G. Pure Ovarian Non-Gestational Choriocarcinoma in a 10-Year Female. Indian J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2024, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.T. Rare Occurrence of Ovarian Choriocarcinoma: Ultrasound Evaluation. J. Ultrasound 2025, 28, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.E.; Fallat, M.E.; Hewitt, G.; Hertweck, P.; Onwuka, A.; Afrazi, A.; Bence, C.; Burns, R.C.; Corkum, K.S.; Dillon, P.A.; et al. Understanding the Value of Tumor Markers in Pediatric Ovarian Neoplasms. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, G.L.; Slater, E.D.; Sanders, G.K.; Prichard, J.G. Serum Tumor Markers. Am. Fam. Physician 2003, 68, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paramita, P.; Preeti, A.; Mili, J.; Ridhi, J.; Mala, S.; Mm, G. Spectrum of Germ Cell Tumor (GCT): 5 Years’ Experience in a Tertiary Care Center and Utility of OCT4 as a Diagnostic Adjunct. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 13, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrazzoli, P.; Rosti, G.; Soresini, E.; Ciani, S.; Secondino, S. Serum Tumour Markers in Germ Cell Tumours: From Diagnosis to Cure. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2021, 159, 103224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabban, J.T.; Zaloudek, C.J. A Practical Approach to Immunohistochemical Diagnosis of Ovarian Germ Cell Tumours and Sex Cord–Stromal Tumours. Histopathology 2013, 62, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieckmann, K.P.; Radtke, A.; Spiekermann, M.; Balks, T.; Matthies, C.; Becker, P.; Ruf, C.; Oing, C.; Oechsle, K.; Bokemeyer, C.; et al. Serum Levels of MicroRNA MiR-371a-3p: A Sensitive and Specific New Biomarker for Germ Cell Tumours. Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, 213–220, Erratum in Eur. Urol. 2017, 71, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, K.Z.; Mosunjac, M.B. Practical Review of Ovarian Sex Cord–Stromal Tumors. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2019, 12, 587–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, N.; Bhatia, R.N. Ovarian Fibroma: A Diagnostic Dilemma. Int. J. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 7, 174–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, S.Y.; Song, T.; Seong, S.J.; Kim, M. La Ovarian-Sparing Local Mass Excision for Ovarian Fibroma/Fibrothecoma in Premenopausal Women. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 185, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, M.; Borzyszkowska, D.; Golara, A.; Lubikowski, J.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. The Role of MicroRNA in the Prognosis and Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Barner, R.; Vinh, T.N.; McManus, K.; Dabbs, D.; Vang, R. SF-1 Is a Diagnostically Useful Immunohistochemical Marker and Comparable to Other Sex cord–stromal Tumor Markers for the Differential Diagnosis of Ovarian Sertoli Cell Tumor. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2008, 27, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Senturk, B.Z.; Parkash, V. Inhibin Immunohistochemical Staining: A Practical Approach for the Surgical Pathologist in the Diagnoses of Ovarian Sex cord–stromal Tumors. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2003, 10, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şakirahmet Şen, D.; Gökmen Karasu, A.F.; Özgün Geçer, M.; Karadayı, N.; Ablan Yamuç, E. Utilization of Wilms’ Tumor 1 Antigen in a Panel for Differential Diagnosis of Ovarian Carcinomas. Turk. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 13, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deavers, M.T.; Malpica, A.; Liu, J.; Broaddus, R.; Silva, E.G. Ovarian Sex cord–stromal Tumors: An Immunohistochemical Study Including a Comparison of Calretinin and Inhibin. Mod. Pathol. 2003, 16, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahedi-Lankarani, S.; Kurman, R.J. Calretinin, a More Sensitive but Less Specific Marker Than α-Inhibin for Ovarian Sex cord–stromal Neoplasms. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002, 26, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Yang, R.; Xu, T.; Li, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts-Derived FMO2 as a Biomarker of Macrophage Infiltration and Prognosis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 167, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnr, G.A.; Das, N.; Singh, K.L. EP766 Clinico-Pathological Features of Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumours. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29, A425–A426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Choi, C.H.; Hong, D.G.; Song, J.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, K.T.; Lee, K.W.; Park, I.S.; Bae, D.S.; Kim, T.J. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Granulosa Cell Tumors of the Ovary: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2011, 22, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.P.; Köbel, M.; Senz, J.; Morin, R.D.; Clarke, B.A.; Ch, B.; Wiegand, K.C.; Leung, G.; Zayed, A.; Mehl, E.; et al. Mutation of FOXL2 in Granulosa-Cell Tumors of the Ovary. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2719–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.T.H.; Fuller, P.J.; Chu, S. Impact of FOXL2 Mutations on Signaling in Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 72, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayoun, B.A.; Caburet, S.; Dipietromaria, A.; Georges, A.; D’Haene, B.; Pandaranayaka, P.J.E.; L’Hôte, D.; Todeschini, A.L.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Fellous, M.; et al. Functional Exploration of the Adult Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumor-Associated Somatic FOXL2 Mutation p.Cys134Trp (c.402C>G). PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, E.; Todeschini, A.L.; Felipe-Medina, N.; Corte-Torres, M.D.; Condezo, Y.B.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; López-Tamargo, S.; Astudillo, A.; Puente, X.S.; Pendas, A.M.; et al. The Oncogenic FOXL2 C134W Mutation Is a Key Driver of Granulosa Cell Tumors. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyubimova, N.V.; Beishembaev, A.M.; Timofeev, Y.S.; Kushlinskii, N.E. Inhibin B in Stromal-Cell Ovarian Tumors. Adv. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 7, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mom, C.H.; Engelen, M.J.A.; Willemse, P.H.B.; Gietema, J.A.; Ten Hoor, K.A.; de Vries, E.G.E.; van der Zee, A.G.J. Granulosa Cell Tumors of the Ovary: The Clinical Value of Serum Inhibin A and B Levels in a Large Single Center Cohort. Gynecol. Oncol. 2007, 105, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portuesi, R.; Loppini, A.; Mancari, R.; Filippi, S.; Colombo, N. Role of Inhibin B in Detecting Recurrence of Granulosa Cell Tumors of the Ovary in Postmenopausal Patients. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, B.; Fan, J. Diagnostic Value of Anti-Mullerian Hormone in Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumor: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2020, 253, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färkkilä, A.; Koskela, S.; Bryk, S.; Alfthan, H.; Bützow, R.; Leminen, A.; Puistola, U.; Tapanainen, J.S.; Heikinheimo, M.; Anttonen, M.; et al. The Clinical Utility of Serum Anti-Müllerian Hormone in the Follow-up of Ovarian Adult-type Granulosa Cell Tumors—A Comparative Study with Inhibin B. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 1661–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, I.; Vergote, I.; Neven, P.; Billen, J. The Role of Inhibins B and Antimüllerian Hormone for Diagnosis and Follow-up of Granulosa Cell Tumors. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, A.; Tate, S.; Nishikimi, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Otsuka, S.; Shozu, M. Serum FSH as a Useful Marker for the Differential Diagnosis of Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14, 4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haltia, U.M.; Pihlajoki, M.; Andersson, N.; Mäkinen, L.; Tapper, J.; Cervera, A.; Horlings, H.M.; Turpeinen, U.; Anttonen, M.; Bützow, R.; et al. Functional Profiling of FSH and Estradiol in Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumors. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvaa034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, G.A.; Hamdy, O.; Ragab, D.; Farouk, B.; Allam, M.M.; Abo Asy, R.; Denewar, F.A.; Ezat, M. Fibrothecoma of the Ovary; Clinical and Imaging Characteristics. Womens Health Rep. 2025, 6, 315–324. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, W. [THECOMA]. An. Paul. Med. Cir. 2020, 86, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duragkar, S.S.; Tayade, S.A.; Dhurve, K.P.; Khandelwal, S. Silent Thecoma of Ovary—A Rare Case. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2020, 9, 2490–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigismondi, C.; Gadducci, A.; Lorusso, D.; Candiani, M.; Breda, E.; Raspagliesi, F.; Cormio, G.; Marinaccio, M.; Mangili, G. Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors. a Retrospective MITO Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, P.; Miland-Samuelsen, A.R.; Smerdel, M.P.; Schnack, T.H.; Lauszus, F.F.; Karstensen, S.H. Sertoli–Leydig Cell Tumor: A Clinicopathological Analysis in a Comprehensive, National Cohort. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2023, 33, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Kock, L.; Terzic, T.; McCluggage, W.G.; Stewart, C.J.R.; Shaw, P.; Foulkes, W.D.; Clarke, B.A. DICER1 Mutations Are Consistently Present in Moderately and Poorly Differentiated Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017, 41, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, K.A.P.; Harris, A.K.; Finch, M.; Dehner, L.P.; Brown, J.B.; Gershenson, D.M.; Young, R.H.; Field, A.; Yu, W.; Turner, J.; et al. DICER1-Related Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor and Gynandroblastoma: Clinical and Genetic Findings from the International Ovarian and Testicular Stromal Tumor Registry. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 147, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paolis, E.; Paragliola, R.M.; Concolino, P. Spectrum of DICER1 Germline Pathogenic Variants in Ovarian Sertoli–Leydig Cell Tumor. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishi, M.; Howard, L.N.; Bratthauer, G.L.; Tavassoli, F.A. Use of Monoclonal Antibody against Human Inhibin as a Marker for Sex cord–stromal Tumors of the Ovary. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1997, 21, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzia, E.; Galiano, V.; Guarnerio, P.P.; Marconi, A.M. Diagnostic Pitfalls in Ovarian Androgen-Secreting Tumors in Postmenopausal Women with Rapidly Progressed Severe Hyperandrogenism. Post. Reprod. Health 2025, 31, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, A.A. The Role of SF1 in Stromal Tumors. J. Med. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 4, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Němejcová, K.; Hájková, N.; Krkavcová, E.; Kendall Bártů, M.; Michálková, R.; Šafanda, A.; Švajdler, M.; Shatokhina, T.; Laco, J.; Matěj, R.; et al. A Molecular and Immunohistochemical Study of 37 Cases of Ovarian Sertoli-Leydig Cell Tumor. Virchows Arch. 2025, 487, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabban, J.T.; Karnezis, A.N.; Devine, W.P. Practical Roles for Molecular Diagnostic Testing in Ovarian Adult Granulosa Cell Tumour, Sertoli–Leydig Cell Tumour, Microcystic Stromal Tumour and Their Mimics. Histopathology 2020, 76, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brink, G.J.; Hami, N.; Nijman, H.W.; Piek, J.M.J.; van Lonkhuijzen, L.R.C.W.; Roes, E.M.; Hofhuis, W.; Lok, C.A.R.; de Kroon, C.D.; Gort, E.H.; et al. The Prognostic Value of FOXL2 Mutant Circulating Tumor DNA in Adult Granulosa Cell Tumor Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.; Oliva, E. Ovarian Sex cord–stromal Tumours: An Update in Recent Molecular Advances. Pathology 2018, 50, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeneweg, J.W.; Roze, J.F.; Peters, E.D.J.; Sereno, F.; Brink, A.G.J.; Paijens, S.T.; Nijman, H.W.; van Meurs, H.S.; van Lonkhuijzen, L.R.C.W.; Piek, J.M.J.; et al. FOXL2 and TERT Promoter Mutation Detection in Circulating Tumor DNA of Adult Granulosa Cell Tumors as Biomarker for Disease Monitoring. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 162, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Vinh, T.N.; McManus, K.; Dabbs, D.; Barner, R.; Vang, R. Identification of the Most Sensitive and Robust Immunohistochemical Markers in Different Categories of Ovarian Sex cord–stromal Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2009, 33, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.; Davey, M.G.; Miller, N. The Potential of MicroRNAs as Clinical Biomarkers to Aid Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Genes 2022, 13, 2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.N.; Chang, R.; Lin, L.-T.; Chern, C.U.; Tsai, H.W.; Wen, Z.H.; Li, Y.H.; Li, C.J.; Tsui, K.H. MicroRNA in Ovarian Cancer: Biology, Pathogenesis, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirahmadi, Y.; Nabavi, R.; Taheri, F.; Samadian, M.M.; Ghale-Noie, Z.N.; Farjami, M.; Samadi-Khouzani, A.; Yousefi, M.; Azhdari, S.; Salmaninejad, A.; et al. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Targeting of Ovarian Cancer. J. Oncol. 2021, 2021, 3408937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biamonte, F.; Santamaria, G.; Sacco, A.; Perrone, F.M.; Di Cello, A.; Battaglia, A.M.; Salatino, A.; Di Vito, A.; Aversa, I.; Venturella, R.; et al. MicroRNA Let-7g Acts as Tumor Suppressor and Predictive Biomarker for Chemoresistance in Human Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, P.W.; Ng, S.W. The Functions of MicroRNA-200 Family in Ovarian Cancer: Beyond Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsaki, M.; Spandidos, D.A.; Zaravinos, A. Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition-Associated MiRNAs in Ovarian Carcinoma, with Highlight on the MiR-200 Family: Prognostic Value and Prospective Role in Ovarian Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Lett. 2014, 351, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanale, D.; Corsini, L.R.; Bono, M.; Randazzo, U.; Barraco, N.; Brando, C.; Cancelliere, D.; Contino, S.; Giurintano, A.; Magrin, L.; et al. Clinical Relevance of Exosome-Derived MicroRNAs in Ovarian Cancer: Looking for New Tumor Biological Fingerprints. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 193, 104220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoi, A.; Matsuzaki, J.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoneoka, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Shimizu, H.; Uehara, T.; Ishikawa, M.; Ikeda, S.-I.; Sonoda, T.; et al. Integrated Extracellular MicroRNA Profiling for Ovarian Cancer Screening. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, B. MicroRNAs as Biomarkers of Ovarian Cancer. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2020, 20, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Wang, H.; Yung, M.M.H.; Chen, F.; Chan, W.S.; Chan, Y.S.; Tsui, S.K.W.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Chan, K.K.L.; Chan, D.W. SCD1/FADS2 Fatty Acid Desaturases Equipoise Lipid Metabolic Activity and Redox-Driven Ferroptosis in Ascites-Derived Ovarian Cancer Cells. Theranostics 2022, 12, 3534–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Lee, S. Fatty Acid Metabolism in Ovarian Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Condello, S.; Thomes-Pepin, J.; Ma, X.; Xia, Y.; Hurley, T.D.; Matei, D.; Cheng, J.X. Lipid Desaturation Is a Metabolic Marker and Therapeutic Target of Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 303–314.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.-S.; Yeom, J.; Yu, J.; Kwon, Y.-I.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, K. Convergence of Plasma Metabolomics and Proteomics Analysis to Discover Signatures of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvo, M.; De Santiago, I.; Gopalacharyulu, P.; Schmitt, W.D.; Budczies, J.; Kuhberg, M.; Dietel, M.; Aittokallio, T.; Markowetz, F.; Denkert, C.; et al. Accumulated Metabolites of Hydroxybutyric Acid Serve as Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Salim, Y.; Galazis, N.; Bracewell-Milnes, T.; Phelps, D.L.; Jones, B.P.; Chan, M.; Munoz-Gonzales, M.D.; Matsuzono, T.; Smith, J.R.; Yazbek, J.; et al. The Application of Metabolomics in Ovarian Cancer Management: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2021, 31, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S.; Mohamed, A.; Krzyslak, H.; Al-Kaabi, L.; Abuhaweeleh, M.; Moustafa, A.-E.; Ghabreau, L.; Vranic, S.; Honoré, B. Proteomic Analysis Reveals Potential Biomarker Candidates in Serous Ovarian Tumors—A Preliminary Study. Contemp. Oncol. 2025, 29, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Sun, R.; Xue, Z.; Guo, T. Mass Spectrometry–Based Proteomics of Epithelial Ovarian Cancers: A Clinical Perspective. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivansson, E.; Hedlund Lindberg, J.; Stålberg, K.; Sundfeldt, K.; Gyllensten, U.; Enroth, S. Large-Scale Proteomics Reveals Precise Biomarkers for Detection of Ovarian Cancer in Symptomatic Women. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sundfeldt, K.; Borrebaeck, C.A.K.; Jakobsson, M.E. Comprehending the Proteomic Landscape of Ovarian Cancer: A Road to the Discovery of Disease Biomarkers. Proteomes 2021, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, T.J.; Erickson, B.K.; Thomas, S.N. Opportunities for Predictive Proteogenomic Biomarkers of Drug Treatment Sensitivity in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1503107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, A.; Arad, G.; Kovalerchik, D.; Manor, A.; Simchi, N.; Daitchman, D.; Pevzner, K.; Seger, E. Abstract 1855: Proteomics Driven Biomarker Discovery for High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma from Archived Tissue Specimens. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Payne, S.H.; Zhang, B.; McDermott, J.E.; Zhou, J.Y.; Petyuk, V.A.; Chen, L.; Ray, D.; et al. Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization of Human High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cell 2016, 166, 755–765, Erratum in Cell 2025, 188, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.Y.; Chapman, J.S.; Kalashnikova, E.; Pierson, W.; Smith-McCune, K.; Pineda, G.; Vattakalam, R.M.; Ross, A.; Mills, M.; Suarez, C.J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Monitoring for Early Recurrence Detection in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2022, 167, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, D.B.; Tierno, D.; Grassi, G.; Scaggiante, B. Circulating Tumour DNA for Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Monitoring: What Perspectives for Clinical Use? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, R.; Ribeiro, I.P.; Figueiredo-Dias, M.; Gourley, C.; Carreira, I.M. Current Applications and Challenges of Next-Generation Sequencing in Plasma Circulating Tumour DNA of Ovarian Cancer. Biology 2024, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Guo, Y.; He, Y.; Cheng, S.; Sun, L.; Teng, J. Value of CtDNA-Based Molecular Residual Disease (MRD) in Evaluating the Adjuvant Therapy Effect in Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 5525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golara, A.; Kozłowski, M.; Cymbaluk-Płoska, A. The Role of Circulating Tumor DNA in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Tang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Xiang, Y. Circulating Tumor DNA: A Noninvasive Biomarker for Tracking Ovarian Cancer. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2021, 19, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharbatoghli, M.; Vafaei, S.; Aboulkheyr Es, H.; Asadi-Lari, M.; Totonchi, M.; Madjd, Z. Prediction of the Treatment Response in Ovarian Cancer: A CtDNA Approach. J. Ovarian Res. 2020, 13, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thusgaard, C.F.; Korsholm, M.; Koldby, K.M.; Kruse, T.A.; Thomassen, M.; Jochumsen, K.M. Epithelial Ovarian Cancer and the Use of Circulating Tumor DNA: A Systematic Review. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaicekauskaitė, I.; Kazlauskaitė, P.; Gineikaitė, R.; Čiurlienė, R.; Lazutka, J.R.; Sabaliauskaitė, R. Integrative Analysis of Gene Expression and Promoter Methylation to Differentiate High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer from Benign Tumors. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbromski, P.J.; Pawlik, P.; Bogacz, A.; Sajdak, S. Identification of New Molecular Biomarkers in Ovarian Cancer Using the Gene Expression Profile. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalfa, F.; Perrone, M.G.; Ferorelli, S.; Laera, L.; Pierri, C.L.; Tolomeo, A.; Dimiccoli, V.; Perrone, G.; De Grassi, A.; Scilimati, A. Genome-Wide Identification and Validation of Gene Expression Biomarkers in the Diagnosis of Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhan, X. Identification of Clinical Trait–Related LncRNA and MRNA Biomarkers with Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis as Useful Tool for Personalized Medicine in Ovarian Cancer. EPMA J. 2019, 10, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talijanovic, M.; Lopacinska-Jørgensen, J.; Høgdall, E.V. Gene Expression Profiles in Ovarian Cancer Tissues as a Potential Tool to Predict Platinum-Based Chemotherapy Resistance. Anticancer Res. 2025, 45, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Liu, L.; Deng, X.; Xing, X.; Zhang, Y.; Djouda Rebecca, Y.; Han, L. Exosomal Biomarkers in the Differential Diagnosis of Ovarian Tumors: The Emerging Roles of CA125, HE4, and C5a. J. Ovarian Res. 2024, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, Y.J.; Saad, R.; Mahdi, M.A.; Jumaa, A.H. Evaluation of LDH, AFP, b-HCG and Tumour Markers CEA and CA-125 in Sera of Iraqi Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Scr. Med. 2025, 56, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, C.E.; Predescu, D.V.; Rusu, C.M.; Radu, B.M.; Cretoiu, D.; Suciu, N.; Crețoiu, S.M.; Voinea, S.C. Role of MicroRNAs as Clinical Cancer Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer: A Short Overview. Cells 2020, 9, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.W.; Charkhchi, P.; Akbari, M.R. Potential Clinical Utility of Liquid Biopsies in Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Siu, M.K.Y.; Ngan, H.Y.S.; Chan, K.K.L. Molecular Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Bi, M.; Guo, H.; Li, M. Multi-Omics Approaches for Biomarker Discovery in Early Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis. eBioMedicine 2022, 79, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terp, S.K.; Stoico, M.P.; Dybkær, K.; Pedersen, I.S. Early Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer Based on Methylation Profiles in Peripheral Blood Cell-Free DNA: A Systematic Review. Clin. Epigenetics 2023, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.L.; Li, X.Y.; Jia, M.Q.; Ma, Q.P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Liu, F.H.; Qin, Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.Y.; et al. AI-Derived Blood Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e67922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abul Rub, F.; Moursy, N.; Alhedeithy, N.; Mohamed, J.; Ifthikar, Z.; Elahi, M.A.; Mir, T.A.; Rehman, M.U.; Tariq, S.; Alabudahash, M.; et al. Modern Emerging Biosensing Methodologies for the Early Diagnosis and Screening of Ovarian Cancer. Biosensors 2025, 15, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, A.; Perumal, V.; Ammalli, P.; Suryan, V.; Bansal, S.K. Diagnostic Measures Comparison for Ovarian Malignancy Risk in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Musalhi, K.; Al Kindi, M.; Al Aisary, F.; Ramadhan, F.; Al Rawahi, T.; Al Hatali, K.; Mula-Abed, W.A. Evaluation of HE4, CA-125, Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) and Risk of Malignancy Index (RMI) in the Preoperative Assessment of Patients with Adnexal Mass. Oman Med. J. 2016, 31, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.M.; Cardenas, C.; Tedja, R. The Role of Intra-Tumoral Heterogeneity and Its Clinical Relevance in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Recurrence and Metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajapaksha, W.; Khetan, R.; Johnson, I.R.D.; Blencowe, A.; Garg, S.; Albrecht, H.; Gillam, T.A. Future Theranostic Strategies: Emerging Ovarian Cancer Biomarkers to Bridge the Gap between Diagnosis and Treatment. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 4, 1339936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagden, S.P. Harnessing Pandemonium: The Clinical Implications of Tumor Heterogeneity in Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2015, 5, 147970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, D.G.; Kumar, K.V.N.; Reddy, K.L.; Charani, M.S.; Gowthami, Y. Biomarkers for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer: A Review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Biol. 2024, 9, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, C.; Carvalho, F.M.; Oliveira, E.I.; Maciel, G.A.R.; Baracat, E.C.; Carvalho, J.P. A Comparison of CA125, HE4, Risk Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA), and Risk Malignancy Index (RMI) for the Classification of Ovarian Masses. Clinics 2012, 67, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Tang, Y.; Deng, M.; Huang, C.; Lan, D.; Nong, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Q. A Combined Biomarker Panel Shows Improved Sensitivity and Specificity for Detection of Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinelli, A.; Vergara, D.; Martignago, R.; Leo, G.; Malvasi, A.; Tinelli, R.; Marsigliante, S.; Maffia, M.; Lorusso, V. Ovarian Cancer Biomarkers: A Focus on Genomic and Proteomic Findings. Curr. Genom. 2007, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arad, G.; Geiger, T. Functional Impact of Protein–RNA Variation in Clinical Cancer Analyses. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2023, 22, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, M.; Colombo, N.; Cerana, N. Precision Medicine in Ovarian Cancer: Disparities and Inequities in Access to Predictive Biomarkers. Pathologica 2024, 116, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.K.; Ding, D.C. Early Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer: A Comprehensive Review of the Advances, Challenges, and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Deng, F.; Chen, J.; Fu, L.; Lei, J.; Xu, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Gao, Q.; Ding, H. Current Data and Future Perspectives on DNA Methylation in Ovarian Cancer (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2024, 64, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffitt, L.R.; Karimnia, N.; Wilson, A.L.; Stephens, A.N.; Ho, G.Y.; Bilandzic, M. Challenges in Implementing Comprehensive Precision Medicine Screening for Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 8023–8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzizadeh, N.; Zarepour, A.; Khosravi, A.; Iravani, S.; Zarrabi, A. Advancing Ovarian Cancer Care: Recent Innovations and Challenges in the Use of MXenes and Their Composites for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 5807–5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtype | Serum Markers | IHC Panels | Genetic/Transcriptomic | Circulating Biomarkers | Proteomic/Metabolomic | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGSOC | Moderate (improved in panels) | High (WT1, p53, multimarker) | High (TP53, BRCA1/2, miRNAs) | High (ctDNA, miRNAs) | High (panels, metabolomics) | [95,96,97,98,101,103,104] |

| CCOC | Low | High (Napsin A, HNF-1β) | Moderate (ARID1A, methylation) | Emerging | Emerging | [98,106] |

| MOC | Low | Moderate (CK7, CK20) | Moderate (KRAS) | Emerging | Emerging | [96,98] |

| EOC | Moderate (best in panels) | High (multimarker) | High (methylation, gene panels) | Moderate | High (panels) | [96,98,106] |

| LGSC | Low | Moderate (WT1, ER, PR) | Moderate (KRAS, BRAF) | Emerging | Emerging | [96,99,106] |

| Subtype | Best Serum Biomarker(s) | Key IHC Marker(s) | Molecular/Genetic | Circulating miRNA | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dysgerminoma | LDH | SALL4, OCT4, PLAP | KIT (subset) | miR-371a-3p | [123,124,172,173,174] |

| Yolk Sac Tumor | AFP | SALL4, GPC3, HNF-1β | Isochromosome 12p | miR-371a-3p | [123,124,151,172,173,174] |

| Choriocarcinoma | β-hCG | SALL4 | - | miR-371a-3p | [173,175] |

| Teratoma | None | SALL4 (immature only) | - | Not expressed | [123,124,172,175] |

| Subtype | Key Serum Markers | Key IHC Markers | Key Genetic Alterations | Diagnostic/Prognostic Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult GCT | Inhibin B, AMH | SF-1, inhibin-α, calretinin, FOXL2 | FOXL2 C134W, TERT promoter | FOXL2 mutation is diagnostic; inhibin B/AMH best for monitoring; TERT mutation = worse prognosis | [180,193,212,213,214,215] |

| Juvenile GCT | Inhibin B, AMH | SF-1, inhibin-α, calretinin | DICER1 (some cases) | DICER1 mutations in subset; similar IHC to AGCT | [206,207,214] |

| SLCT | Inhibin B | SF-1, inhibin-α, calretinin, FOXL2 | DICER1 (most), FOXL2 (rare), TERT (rare) | DICER1 mutations in most; IHC panel highly sensitive | [180,206,207,211,212,216] |

| Thecoma | Inhibin B (variable) | SF-1, inhibin-α, calretinin | Non-specific | IHC confirms diagnosis; serum markers less reliable | [214] |

| Biomarker | Tumor Type | Implication | Sensitivity/Specificity | Clinical Significance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA-125 | HGSOC, EOC | For screening and disease monitoring | 63–83%/71–83% | Well-established, used alone shows limited value, enhanced in combination with HE4 | [36,37,49,98] |

| HE4 | HGSOC, EOC | Most effective for differentiating between benign and malignant masses | 64–75% | A superior tool compared with CA-125, though the combination of both and Smac protein yields optimal sensitivity, but low specificity | [36,37,49,50,98] |

| WT1, PAX8 | HGSOC | For screening | >90%/low specificity | Beneficial in the process of diagnostic differentiation | [44] |

| IMP3, Napsin A, HNF-1β | CCOC | Compromised as a panel | >80%/>80% | Beneficial in the process of diagnostic differentiation | [57] |

| IFITM1 | CCOC | For disease monitoring/prognostic | - | It is one of the proteins that is correlated with recurrence-free survival | [63] |

| CK7+, SATB2- | MOC | Role in distinguishing primary ovarian mucinous tumors from colorectal and appendiceal metastases | 78%/99% | The most critical panel in MOC that outperforms traditional panels | [70,71,72] |

| SALL4 | GCT | For disease detection and diagnostic differentiation | 73%/high specificity | It is consistently expressed in germ cell tumors, only rarely observed in non-germ cell tumors, and absent in mature teratomas | [119,124] |

| OCT4 | Most dysgerminomas | For disease detection and diagnostic differentiation | - | OCT4 is highly specific, because all or nearly all dysgerminomas are OCT4-positive | [133,134,135] |

| AFP | YST | For disease detection and diagnostic differentiation. | Moderate/97.7% | All ovarian YSTs show markedly elevated serum AFP levels, while they are rarely positive in other ovarian tumors | [144,145,152,153] |

| GPC3 | YST | For disease detection and diagnostic differentiation. | - | especially valuable for distinguishing YST from clear cell carcinoma and other germ cell tumors, as it is negative in teratomas, embryonal carcinomas, and germinomas | [154,155,156,157] |

| β-hCG | choriocarcinoma | For diagnosis, treatment monitoring, and recurrence detection | - | Elevated β-hCG, in combination with imaging findings, strongly suggests choriocarcinoma | [167,168,169] |

| Inhibin B | GCT, thecoma | For diagnosis and disease monitoring | 89–98%/81–93% | Beneficial in the process of diagnostic differentiation, both Inhibin B and AMH together further improve detection rates for recurrent disease | [192,193,195,196] |

| Marker Category | Specific Marker/Feature | Biological Role/Correlation | Clinical Application | References |