The Role of Transient Crosslinks in the Chromatin Search Response to DNA Damage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

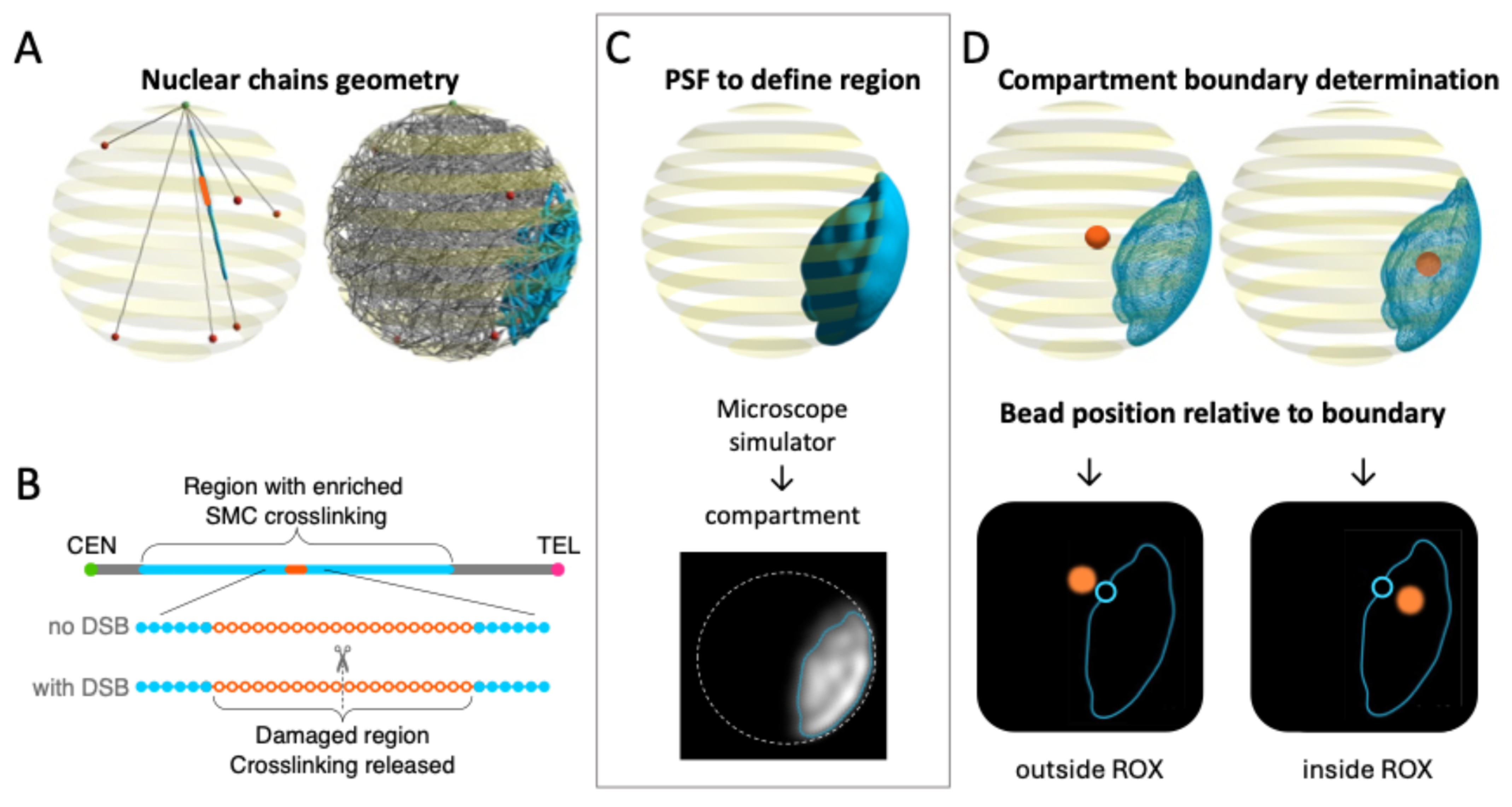

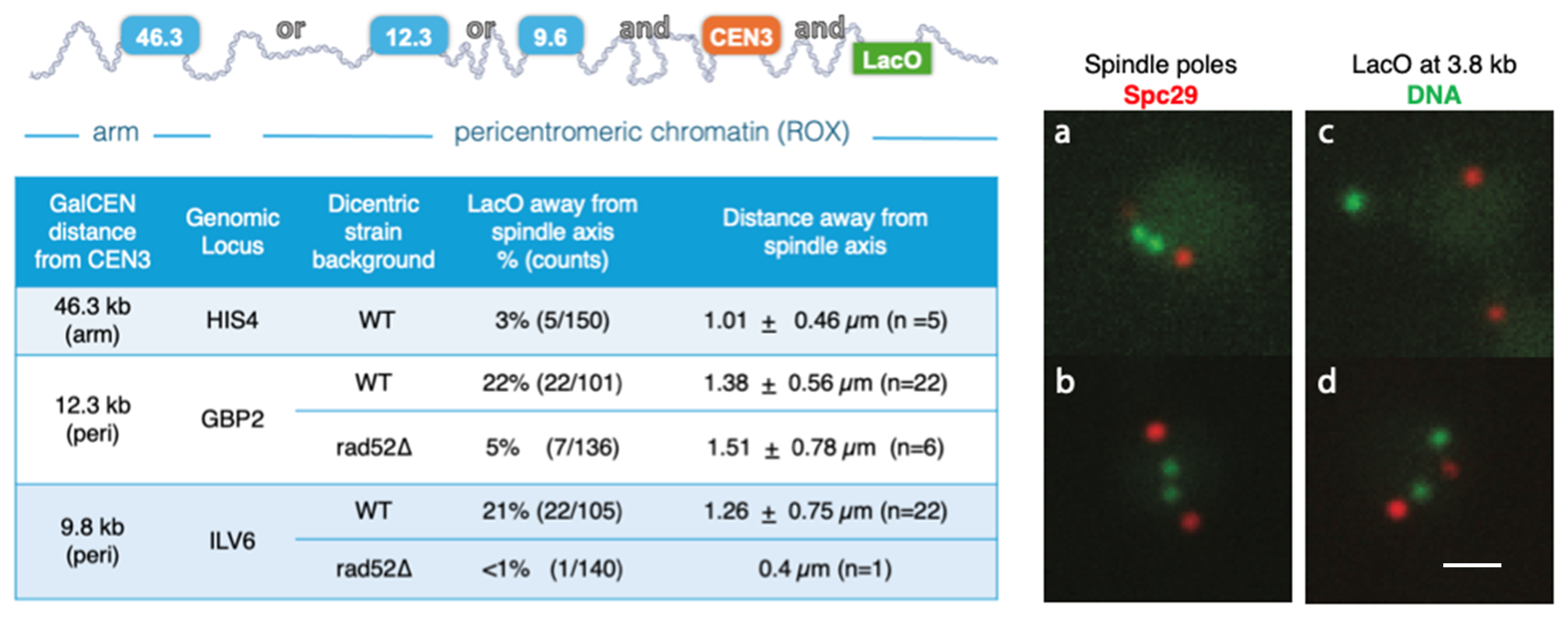

2.1. Determination and Visualization of the ROX Boundary

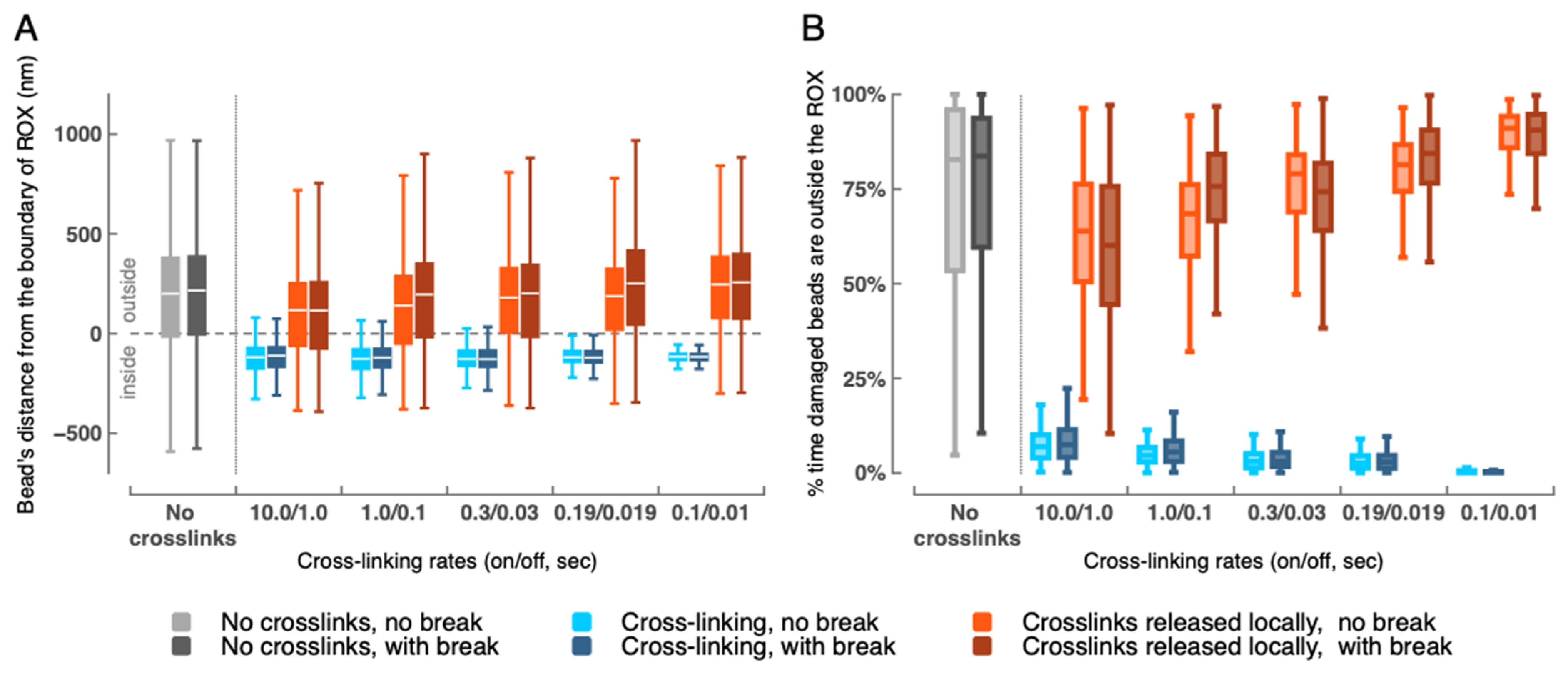

2.2. Depletion of Cross-Links Enables Eviction of the Damaged Region (20 Beads) from the ROX Compartment

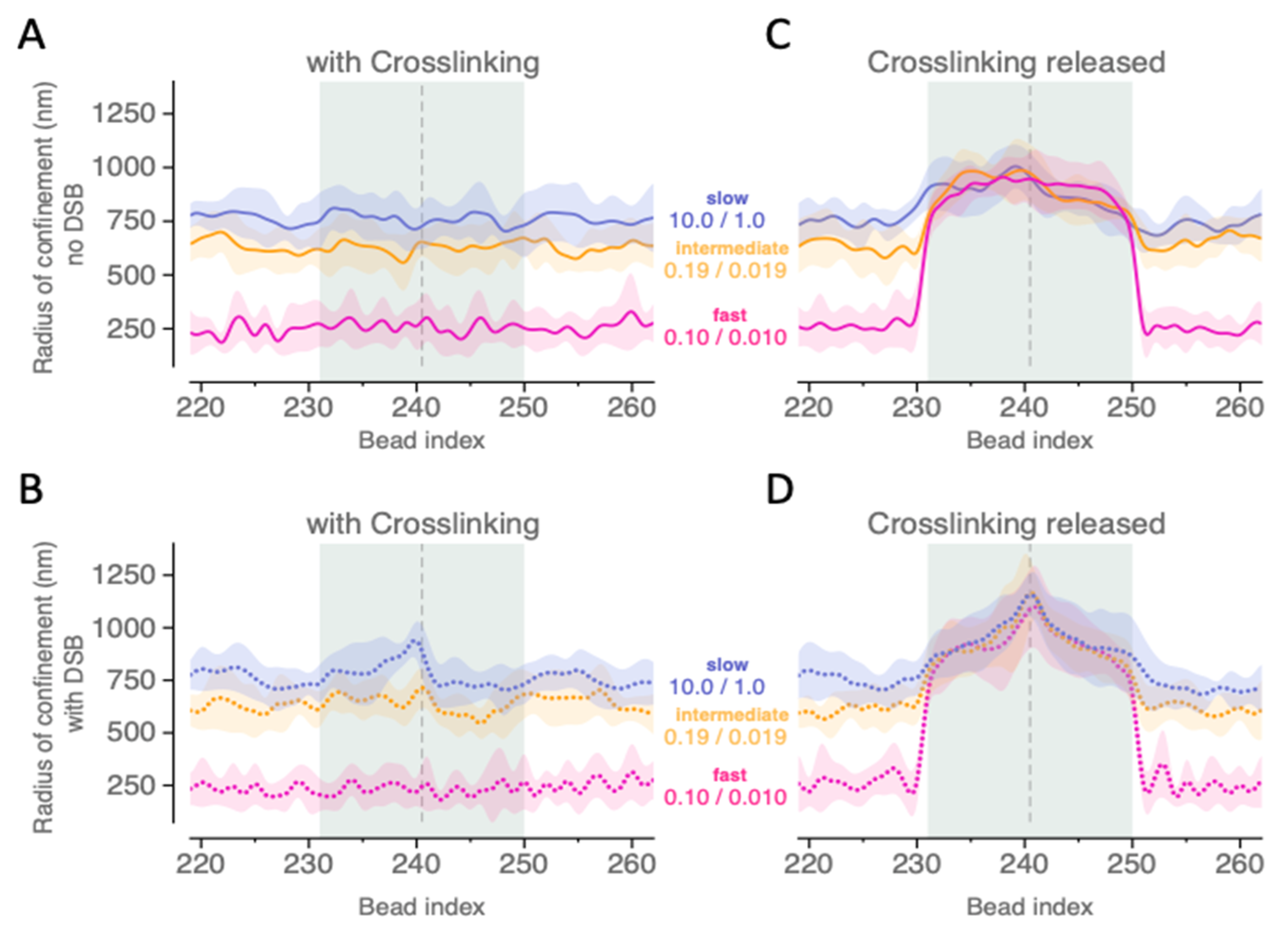

2.3. Depletion of Crosslinks Proximal to the Break Increases the Area of Exploration of Affected Region

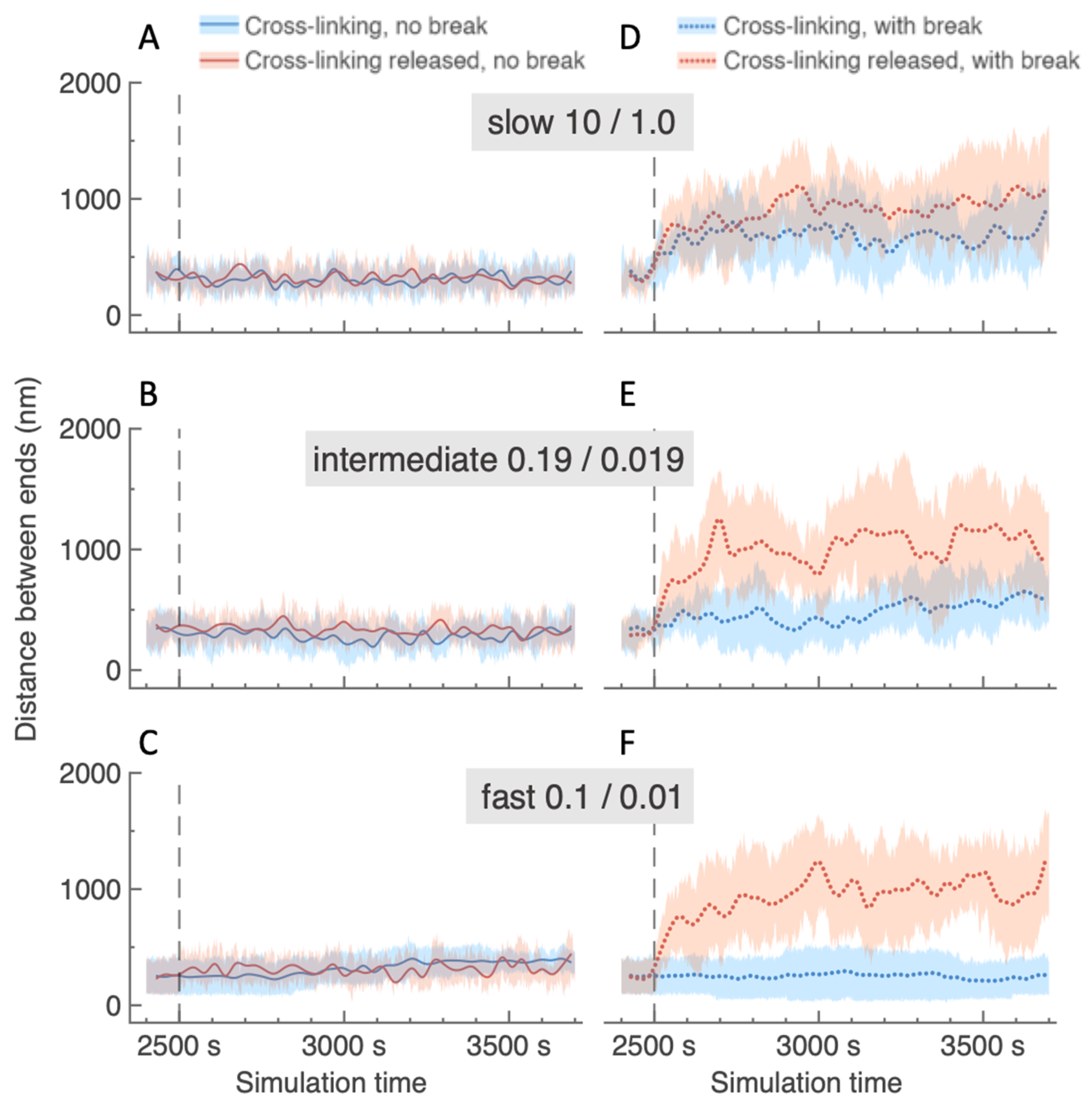

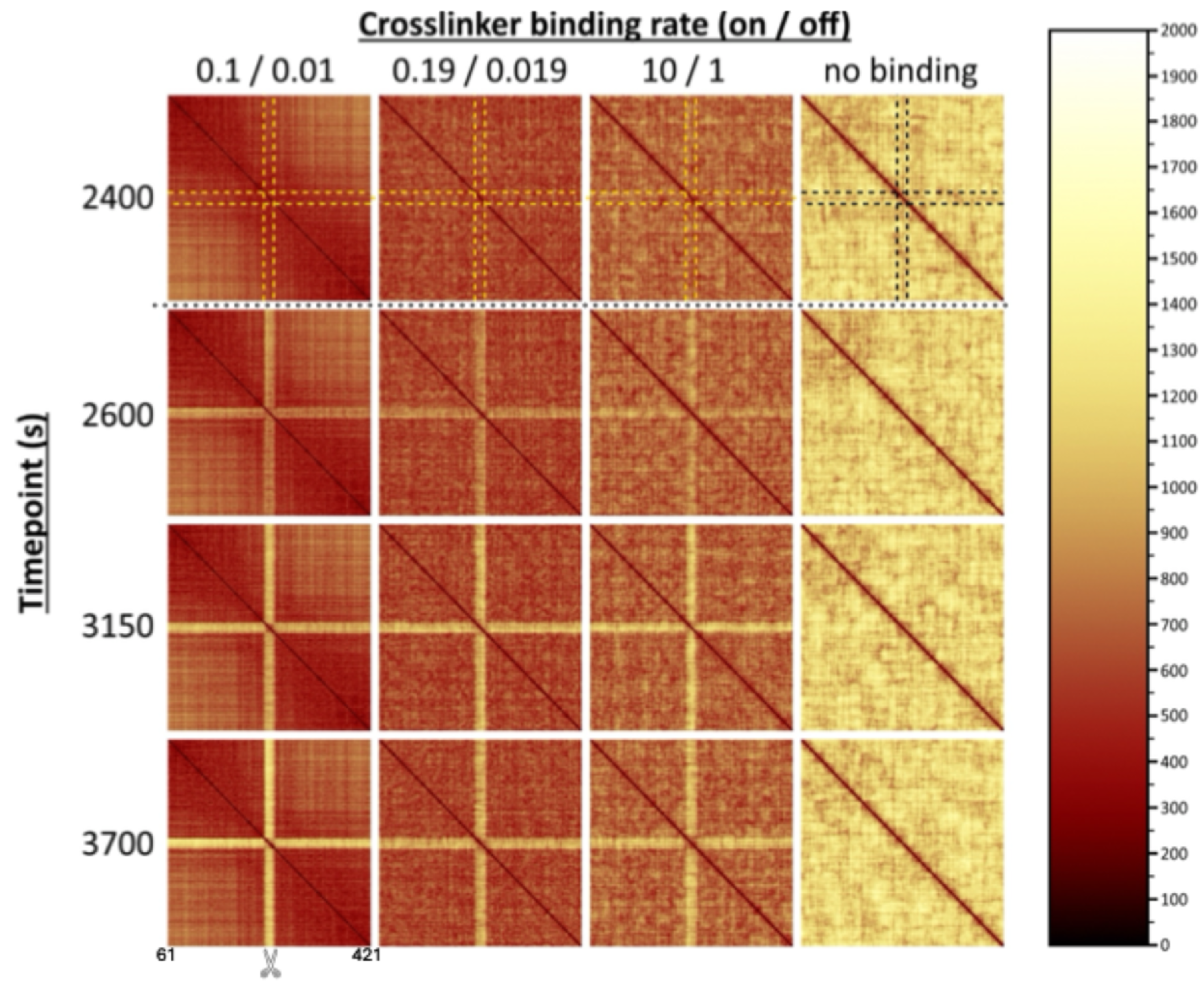

2.4. Local Depletion of Cross-Links Amplifies Distance Between Damaged Ends Following a DSB, Regardless of Crosslinking Rate Elsewhere in the ROX

2.5. Depletion of Cross-Links Has Primarily Local Rather than Global Effects

2.6. Pericentric Chromatin Is Displaced from the Bottlebrush upon DNA Damage

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Materials and Methods

4.2. List of Strains: Yeast Strains Numbers (Genotypes) Used in Experiments

4.3. Simulation Parameters and Data Collection

- (i)

- Double-strand break in the chromosome. In the first approach, we cut or “break” a chromosome arm at a designated point in time by permanently removing the WLC spring that connects two specific neighboring beads. Note that we refer here to the standard, entropic spring force that exists between neighboring beads on the bead-spring chain, not the stronger transient spring force that corresponds to a dynamic crosslink between two beads. We choose a break site near the center of the ROX, as seen in Figure 1B. Beads 61 through 421 of the right arm of chromosome XII (361 beads in total) correspond to the ROX (Figure 1A), and the break occurs between beads 240 and 241 (i.e., ~1.2 Mbps from CEN12).

- (ii)

- Local depletion of SMC proteins. In our second approach, we depleted SMC proteins (protein-mediated cross-links) near the break site. We simulate this depletion in the model by permanently removing selected beads in the ROX from the pool of beads that are able to dynamically cross-link. More specifically, we require that, from a specific point in time onwards, the 20 beads representing the damaged region of the ROX (i.e., the 10 beads on each side of the break site, corresponding to ~50 Kb each, based on the distribution of modified histone (isoform H2AX) at sites of DNA damage [59]) release their cross-links and are no longer eligible to form dynamic cross-links. We set the time of this depletion to be 2500 s after the start of the simulation, i.e., at the same time as the DSB.

4.4. Distance to Edge of ROX Domain

4.5. Radius of Confinement

4.6. Distance Between Cut Ends

4.7. Point Cloud Overlap

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krejci, L.; Altmannova, V.; Spirek, M.; Zhao, X. Homologous Recombination and Its Regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 5795–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pâques, F.; Haber, J.E. Multiple Pathways of Recombination Induced by Double-Strand Breaks in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 349–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccia, A.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA Damage Response: Making It Safe to Play with Knives. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cejka, P.; Symington, L.S. DNA End Resection: Mechanism and Control. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2021, 55, 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borst, P.; Greaves, D.R. Programmed Gene Rearrangements Altering Gene Expression. Science 1987, 235, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, S.M.; Fijen, C.; Rothenberg, E. V(D)J Recombination: Recent Insights in Formation of the Recombinase Complex and Recruitment of DNA Repair Machinery. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 886718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, K. Programmed DNA Elimination. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, R843–R847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Davis, R.E. Programmed DNA Elimination in Multicellular Organisms. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2014, 27, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagoskin, M.V.; Wang, J. Programmed DNA Elimination: Silencing Genes and Repetitive Sequences in Somatic Cells. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 1891–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian, A.B.; Comeron, J.M. The Drosophila Early Ovarian Transcriptome Provides Insight to the Molecular Causes of Recombination Rate Variation across Genomes. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Alani, E.; Kleckner, N. A Pathway for Generation and Processing of Double-Strand Breaks during Meiotic Recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell 1990, 61, 1089–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhler, C.; Borde, V.; Lichten, M. Mapping Meiotic Single-Strand DNA Reveals a New Landscape of DNA Double-Strand Breaks in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e324, Erratum in PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e104 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.R.; Gutiérrez-Velasco, S.; Martín-Castellanos, C.; Smith, G.R. Protein Determinants of Meiotic DNA Break Hot Spots. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Haber, J.E. Mating-Type Gene Switching in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Microbiol. Spectr. 2015, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thon, G.; Maki, T.; Haber, J.E.; Iwasaki, H. Mating-Type Switching by Homology-Directed Recombinational Repair: A Matter of Choice. Curr. Genet. 2019, 65, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.J.; Wolfe, K.H. An Evolutionary Perspective on Yeast Mating-Type Switching. Genetics 2017, 206, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbin, D.; Locatelli, M.; Stanton, J.; Kesselman, K.; Kokkanti, A.; Li, J.; Yeh, E.; Bloom, K. Centromeres Are Stress-Induced Fragile Sites. Curr. Biol. 2025, 35, 1197–1210.E4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsson, L. Chromatin Compaction by Condensin I, Intra-Kinetochore Stretch and Tension, and Anaphase Onset, in Collective Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Interaction. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 26, 155102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lima, L.G.; Guarracino, A.; Koren, S.; Potapova, T.; McKinney, S.; Rhie, A.; Solar, S.J.; Seidel, C.; Fagen, B.L.; Walenz, B.P.; et al. The Formation and Propagation of Human Robertsonian Chromosomes. Nature 2025, 647, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, P.M.; Borovski, T.; Stap, J.; Cijsouw, A.; Ten Cate, R.; Medema, J.P.; Kanaar, R.; Franken, N.A.P.; Aten, J.A. Chromatin Mobility Is Increased at Sites of DNA Double-Strand Breaks. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, M.; Lawrimore, J.; Lin, H.; Sanaullah, S.; Seitz, C.; Segall, D.; Kefer, P.; Salvador Moreno, N.; Lietz, B.; Anderson, R.; et al. DNA Damage Reduces Heterogeneity and Coherence of Chromatin Motions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205166119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miné-Hattab, J.; Recamier, V.; Izeddin, I.; Rothstein, R.; Darzacq, X. Multi-Scale Tracking Reveals Scale-Dependent Chromatin Dynamics after DNA Damage. MBoC 2017, 28, 3323–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maclay, T.M.; Whalen, J.M.; Johnson, M.J.; Freudenreich, C.H. The DNA Replication Checkpoint Targets the Kinetochore to Reposition DNA Structure-Induced Replication Damage to the Nuclear Periphery. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeber, A.; Hauer, M.H.; Gasser, S.M. Chromosome Dynamics in Response to DNA Damage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strecker, J.; Gupta, G.D.; Zhang, W.; Bashkurov, M.; Landry, M.-C.; Pelletier, L.; Durocher, D. DNA Damage Signalling Targets the Kinetochore to Promote Chromatin Mobility. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.J.; Bryant, E.E.; Rothstein, R. Increased Chromosomal Mobility after DNA Damage Is Controlled by Interactions between the Recombination Machinery and the Checkpoint. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miné-Hattab, J.; Rothstein, R. Increased Chromosome Mobility Facilitates Homology Search during Recombination. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, C.; Adalsteinsson, D.; Vasquez, P.A.; Lawrimore, J.; Bennett, M.; York, A.; Cook, D.; Yeh, E.; Forest, M.G.; Bloom, K. Enrichment of Dynamic Chromosomal Crosslinks Drive Phase Separation of the Nucleolus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 11159–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Taylor, D.; Lawrimore, J.; Hult, C.; Adalsteinsson, D.; Bloom, K.; Forest, M.G. Transient Crosslinking Kinetics Optimize Gene Cluster Interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockrell, A.J.; Gerton, J.L. Nucleolar Organizer Regions as Transcription-Based Scaffolds of Nucleolar Structure and Function. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 2022, 70, 551–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rosell, J.; Sunjevaric, I.; De Piccoli, G.; Sacher, M.; Eckert-Boulet, N.; Reid, R.; Jentsch, S.; Rothstein, R.; Aragón, L.; Lisby, M. The Smc5–Smc6 Complex and SUMO Modification of Rad52 Regulates Recombinational Repair at the Ribosomal Gene Locus. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Long, S.; Stanton, J.; Cusick, P.; Lawrimore, C.; Yeh, E.; Grant, S.; Bloom, K. Behavior of Dicentric Chromosomes in Budding Yeast. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, K.; Costanzo, V. Centromere Structure and Function. In Centromeres and Kinetochores: Discovering the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Chromosome Inheritance; Black, B.E., Ed.; Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 515–539. ISBN 978-3-319-58592-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrimore, C.J.; Bloom, K. Common Features of the Pericentromere and Nucleolus. Genes 2019, 10, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paldi, F.; Alver, B.; Robertson, D.; Schalbetter, S.A.; Kerr, A.; Kelly, D.A.; Baxter, J.; Neale, M.J.; Marston, A.L. Convergent Genes Shape Budding Yeast Pericentromeres. Nature 2020, 582, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Gawel, M.; Dominska, M.; Greenwell, P.W.; Hazkani-Covo, E.; Bloom, K.; Petes, T.D. Nonrandom Distribution of Interhomolog Recombination Events Induced by Breakage of a Dicentric Chromosome in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Genetics 2013, 194, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, P.A.; Hult, C.; Adalsteinsson, D.; Lawrimore, J.; Forest, M.G.; Bloom, K. Entropy Gives Rise to Topologically Associating Domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 5540–5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, T.; Cremer, M.; Hübner, B.; Silahtaroglu, A.; Hendzel, M.; Lanctôt, C.; Strickfaden, H.; Cremer, C. The Interchromatin Compartment Participates in the Structural and Functional Organization of the Cell Nucleus. Bioessays 2020, 42, e1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, S.; Tamura, S.; Maeshima, K. Chromatin Behavior in Living Cells: Lessons from Single-Nucleosome Imaging and Tracking. Bioessays 2022, 44, e2200043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Li, W.; Tjong, H.; Hao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, L.; Zhu, B.; Alber, F.; Zhou, X.J. Mining 3D Genome Structure Populations Identifies Major Factors Governing the Stability of Regulatory Communities. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Yu, H. The Smc Complexes in DNA Damage Response. Cell Biosci. 2012, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, T.L.; Uhlmann, F. SMC Complexes: Lifting the Lid on Loop Extrusion. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2022, 74, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenkamp, R.; Rowland, B.D. A Walk through the SMC Cycle: From Catching DNAs to Shaping the Genome. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 1616–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Fernández, F.; Fabre, E. The Dynamic Behavior of Chromatin in Response to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Genes 2022, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haaf, T.; Schmid, M. Chromosome Topology in Mammalian Interphase Nuclei. Exp. Cell Res. 1991, 192, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.; Rippe, K. Repetitive RNAs as Regulators of Chromatin-Associated Subcompartment Formation by Phase Separation. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 4270–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdel, F.; Rippe, K. Formation of Chromatin Subcompartments by Phase Separation. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 2262–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, R.; Hristova, R.; Stoynov, S.; Gospodinov, A. The Chromatin Response to Double-Strand DNA Breaks and Their Repair. Cells 2020, 9, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, C.; Di Nisio, E.; Galli, M.; Colombo, C.V.; Negri, R.; Clerici, M. The Chromatin Landscape around DNA Double-Strand Breaks in Yeast and Its Influence on DNA Repair Pathway Choice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, T.T.; Rogakou, E.P.; Yamazaki, V.; Kirchgessner, C.U.; Gellert, M.; Bonner, W.M. A Critical Role for Histone H2AX in Recruitment of Repair Factors to Nuclear Foci after DNA Damage. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Heidinger-Pauli, J.M.; Koshland, D. DNA Double-Strand Breaks Trigger Genome-Wide Sister-Chromatid Cohesion Through Eco1 (Ctf7). Science 2007, 317, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, E.; Arbel-Eden, A.; Sattler, U.; Shroff, R.; Lichten, M.; Haber, J.E.; Koshland, D. DNA Damage Response Pathway Uses Histone Modification to Assemble a Double-Strand Break-Specific Cohesin Domain. Mol. Cell 2004, 16, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, J.A.; Gasser, S.M. Chromatin Remodeling and Spatial Concerns in DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2024, 90, 102405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Moon, J.; Cai, C.; Hao, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, W.; Zhao, F.; Lou, Z. The Interplay between Chromatin Remodeling and DNA Double-Strand Break Repair: Implications for Cancer Biology and Therapeutics. DNA Repair 2025, 146, 103811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, Ö.Z.; Vermeulen, W.; Lans, H. ISWI Chromatin Remodeling Complexes in the DNA Damage Response. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 3016–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofa, M.G.; Morshed, S.; Shibata, R.; Takeichi, Y.; Rahman, M.A.; Hosoyamada, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Ushimaru, T. rDNA Condensation Promotes rDNA Separation from Nucleolar Proteins Degraded for Nucleophagy after TORC1 Inactivation. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3423–3434.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeshima, K. The Shifting Paradigm of Chromatin Structure: From the 30-Nm Chromatin Fiber to Liquid-like Organization. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2025, 101, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrimore, J.; Kolbin, D.; Stanton, J.; Khan, M.; de Larminat, S.C.; Lawrimore, C.; Yeh, E.; Bloom, K. The rDNA Is Biomolecular Condensate Formed by Polymer-Polymer Phase Separation and Is Sequestered in the Nucleolus by Transcription and R-Loops. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 4586–4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.; Arbel-Eden, A.; Pilch, D.; Ira, G.; Bonner, W.M.; Petrini, J.H.; Haber, J.E.; Lichten, M. Distribution and Dynamics of Chromatin Modification Induced by a Defined DNA Double-Strand Break. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 1703–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdaasdonk, J.S.; Vasquez, P.A.; Barry, R.M.; Barry, T.; Goodwin, S.; Forest, M.G.; Bloom, K. Centromere Tethering Confines Chromosome Domains. Mol. Cell 2013, 52, 819–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crosslinking Rate (on/off) in s | Break Induced | Cross-Links Released Locally | Number of Independent Runs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1/0.01 | no | no | 10 |

| yes | 10 | ||

| yes | no | 10 | |

| yes | 10 | ||

| 0.19/0.019 | no | no | 10 |

| yes | 10 | ||

| yes | no | 10 | |

| yes | 10 | ||

| 0.3/0.03 | no | no | 10 |

| yes | 10 | ||

| yes | no | 10 | |

| yes | 10 | ||

| 1/0.1 | no | no | 10 |

| yes | 10 | ||

| yes | no | 10 | |

| yes | 10 | ||

| 10/1 | no | no | 10 |

| yes | 10 | ||

| yes | no | 10 | |

| yes | 10 | ||

| None (no crosslinking) | no | n/a (not applicable) | 10 |

| yes | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atanasiu, A.T.; Hult, C.; Kolbin, D.; Walker, B.L.; Forest, M.G.; Yeh, E.; Bloom, K. The Role of Transient Crosslinks in the Chromatin Search Response to DNA Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311697

Atanasiu AT, Hult C, Kolbin D, Walker BL, Forest MG, Yeh E, Bloom K. The Role of Transient Crosslinks in the Chromatin Search Response to DNA Damage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311697

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtanasiu, Andrew T., Caitlin Hult, Daniel Kolbin, Benjamin L. Walker, Mark Gregory Forest, Elaine Yeh, and Kerry Bloom. 2025. "The Role of Transient Crosslinks in the Chromatin Search Response to DNA Damage" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311697

APA StyleAtanasiu, A. T., Hult, C., Kolbin, D., Walker, B. L., Forest, M. G., Yeh, E., & Bloom, K. (2025). The Role of Transient Crosslinks in the Chromatin Search Response to DNA Damage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11697. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311697