Nonspecific Binding of a Putative S-Layer Protein to Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides—Implication for Growth Competence of Lactobacillus brevis in the Gut Microbiota

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

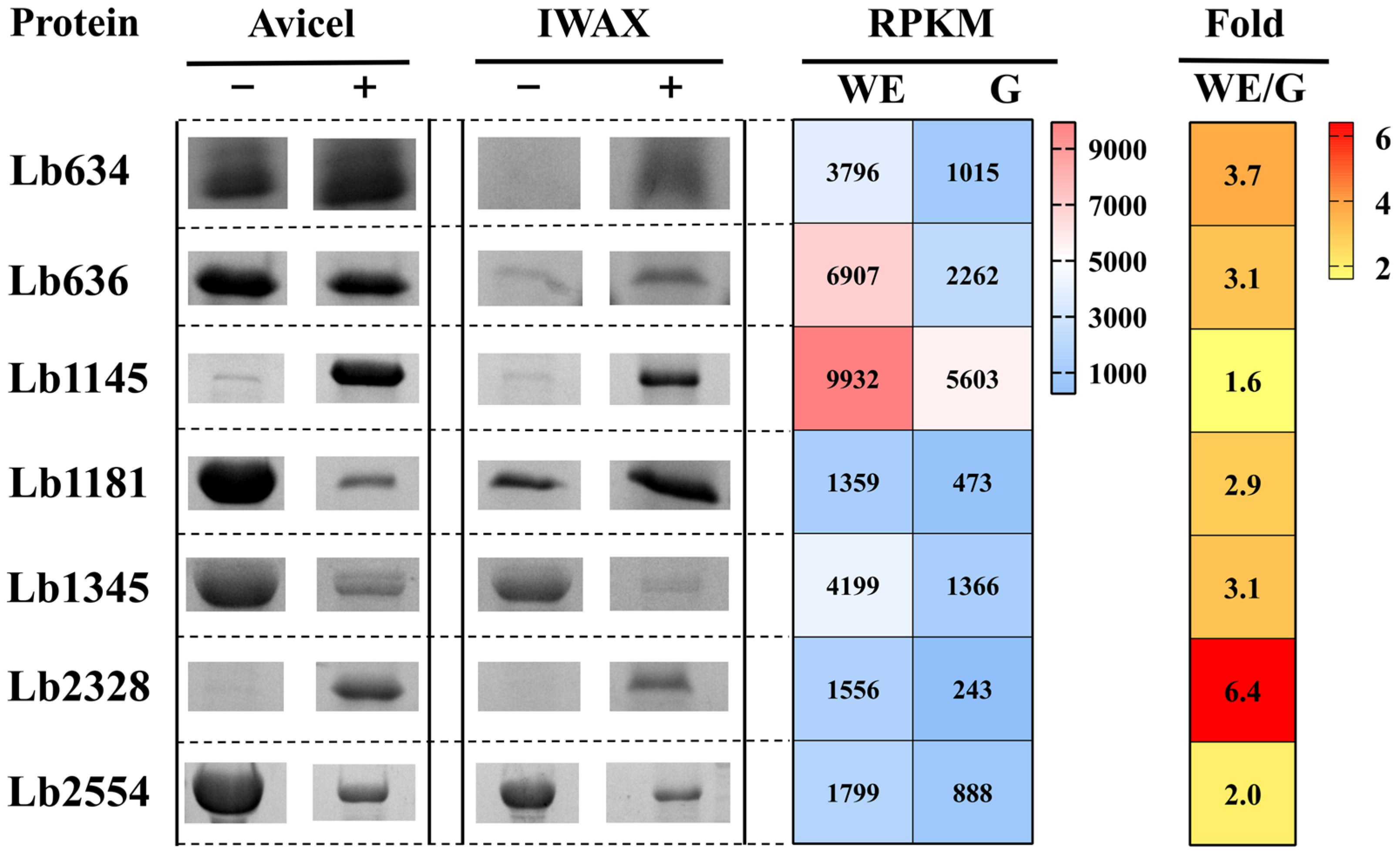

2.1. Identification of Plant Cell Wall-Binding Proteins from L. brevis

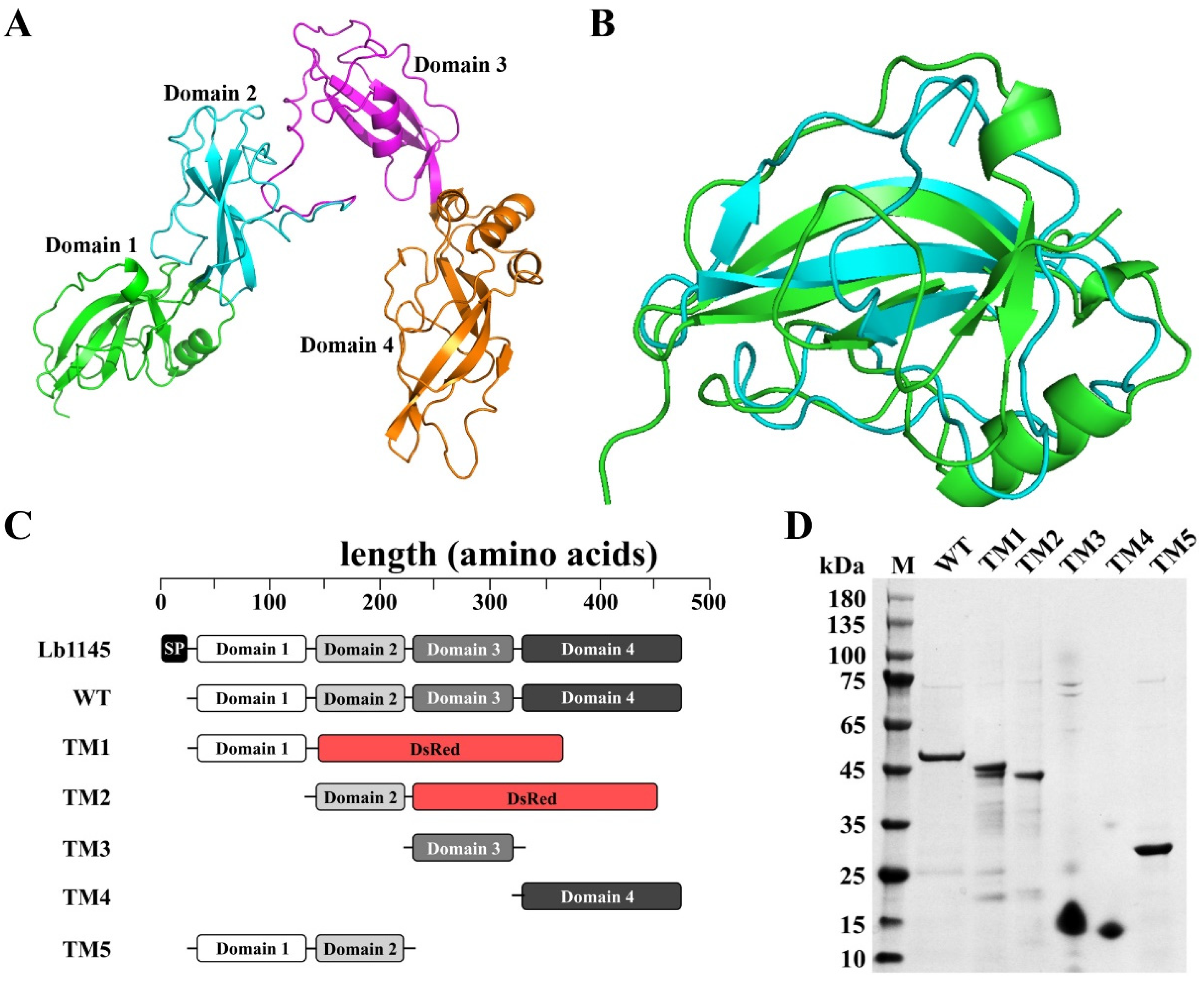

2.2. Delineation of Lb1145 into Four Domains

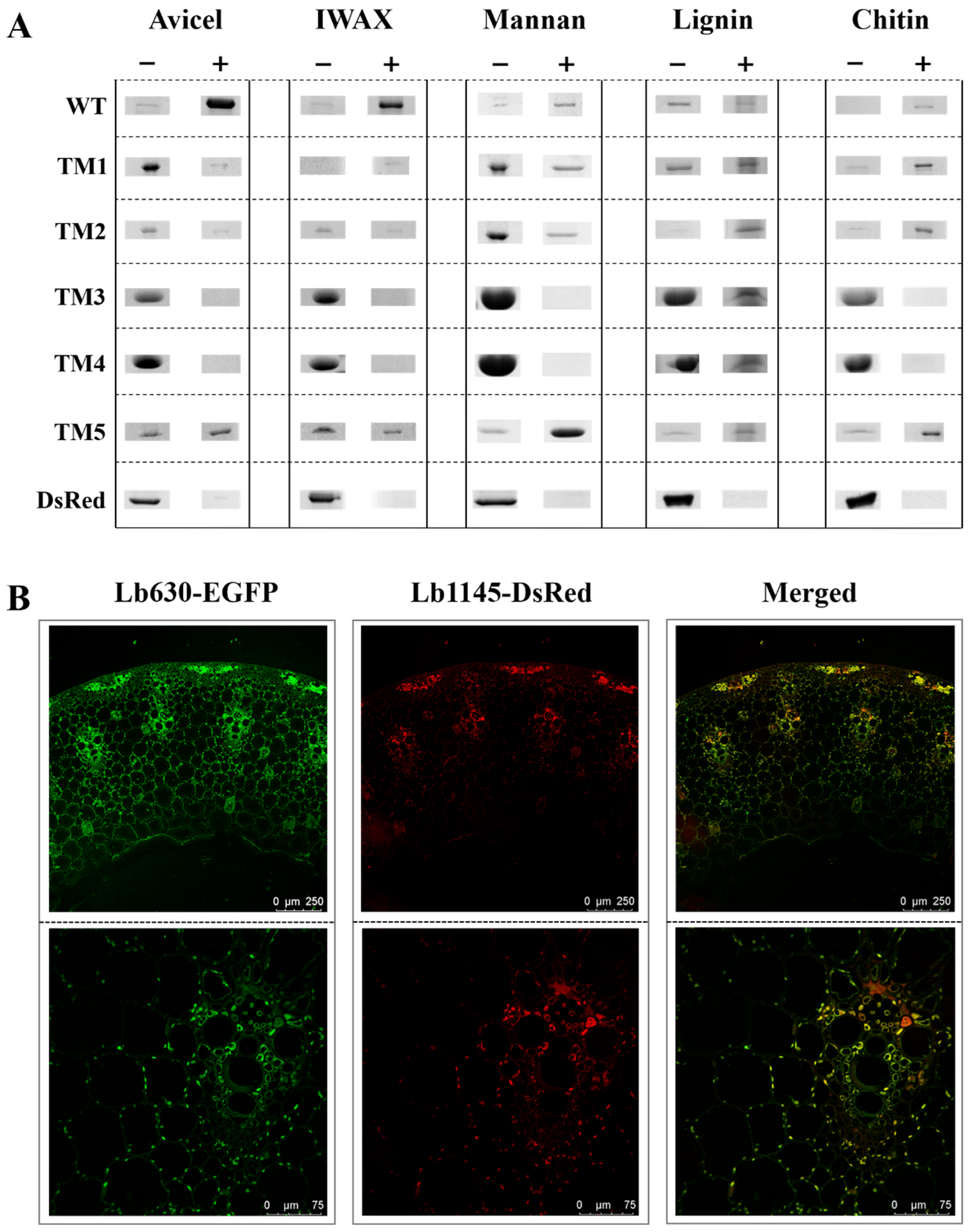

2.3. The Two N-Terminal Domains of Lb1145 Are Responsible for Nonspecific Binding

2.4. Binding of Lb1145 to the Wheat Stem

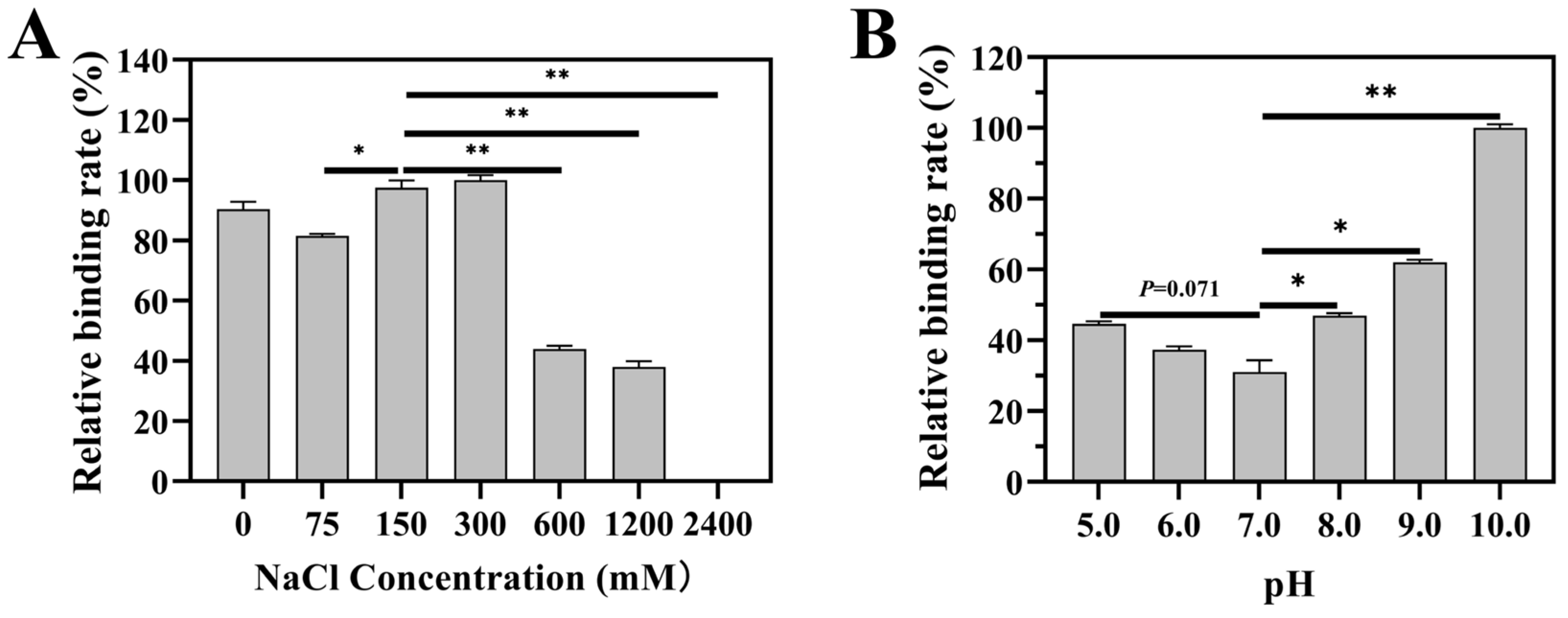

2.5. Involvement of a Non-Enzymatic Glycosylation-like Process in Binding of Lb1145 to PCWPs

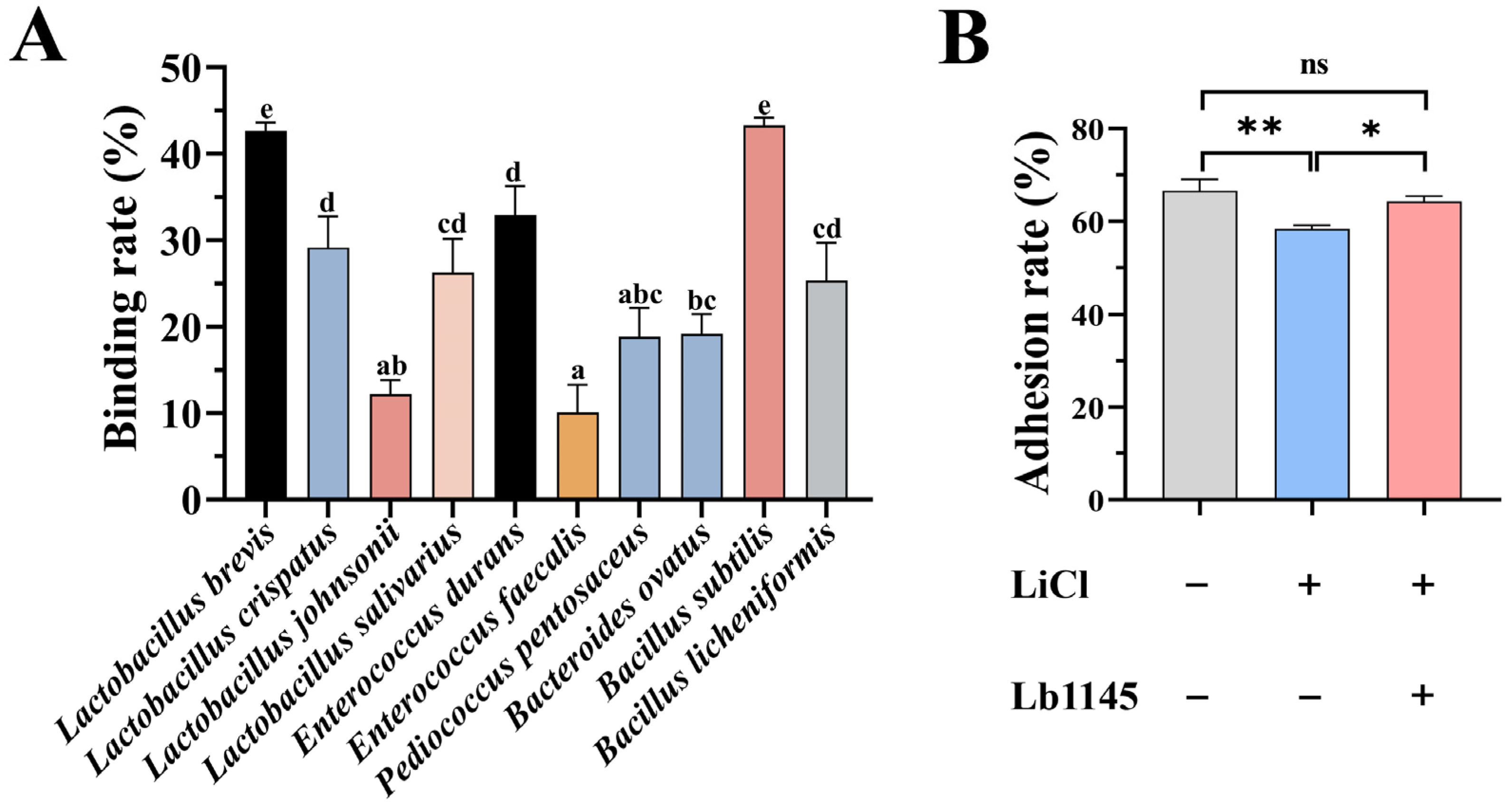

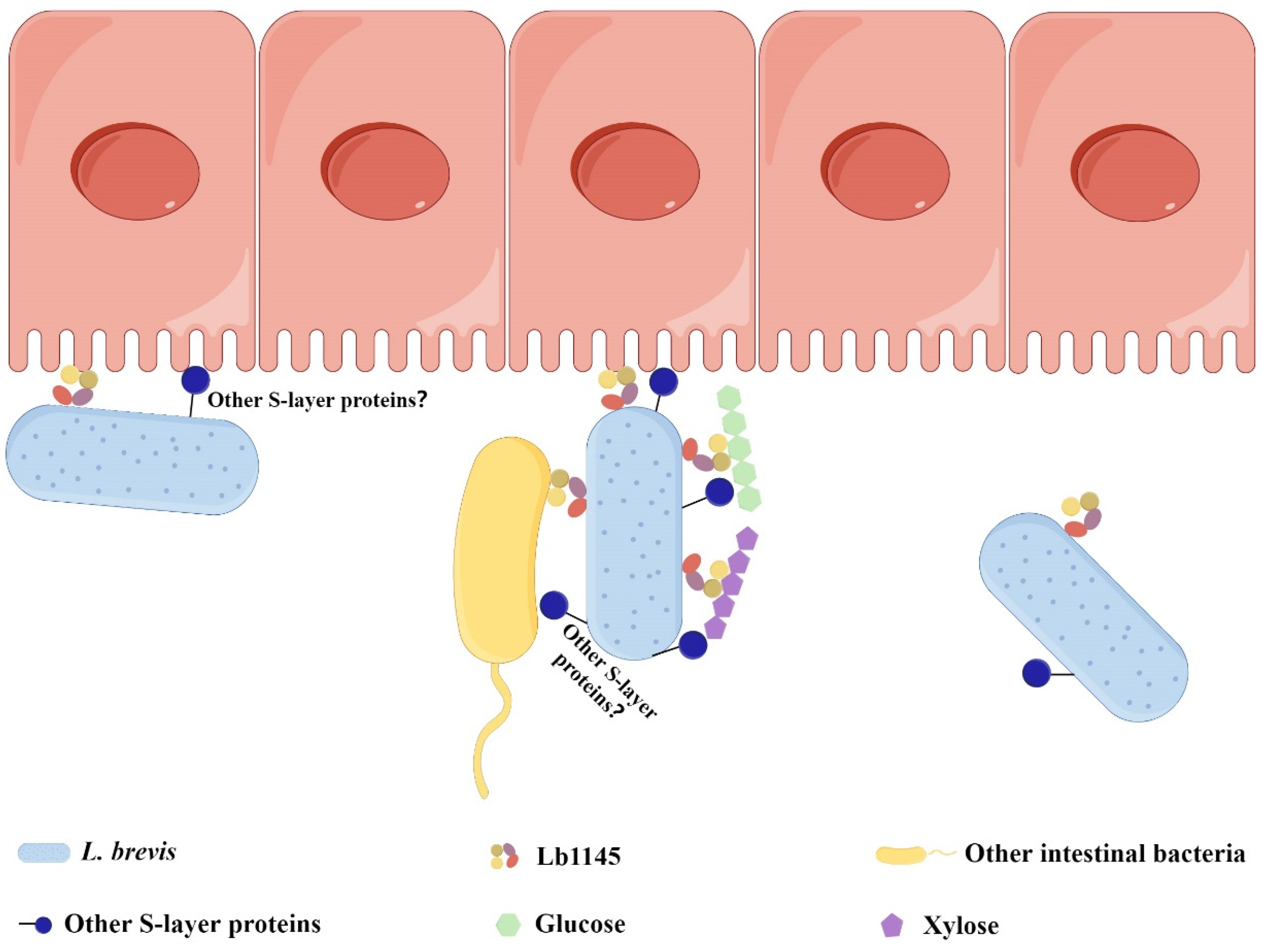

2.6. Binding of Lb1145 to Gut Bacteria

2.7. Lb1145 Partially Restored the Adhesion of LiCl-Treated L. brevis to the Intestinal Epithelial Cell IPEC-J2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Microbial Strains and Culture

4.2. Gene Cloning, Expression, and Protein Purification

4.3. Monitoring Binding of 1145 to L. brevis Using a Confocal Microscope

4.4. Binding of the Recombinant L. brevis Putative Surface Proteins to Insoluble PCWPs, Lignin, and Chitin

4.5. Measuring the Protein–Glucose Amadori Conjugate Using a Nitroblue Tetrazolium Method

4.6. Effect of NaCl and pH on the Binding of the Recombinant Lb1145 TM5 to Cellulose

4.7. Binding of the Recombinant Putative L. brevis Surface Proteins to the Wheat Stem Tissue

4.8. Binding of Lb1145 to Selected Intestinal Bacteria

4.9. Determining Adhesion of L. brevis to the Intestinal Epithelial Cells IPEC-J2

4.10. Statistical Analysis

4.11. Data Availability

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carding, S.; Verbeke, K.; Vipond, D.T.; Corfe, B.M.; Owen, L.J. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 2015, 26, 26191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, K. The burden of chronic disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innov. Qual. Outcomes 2024, 8, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.C.; Lowe, E.C.; Chiang, H.; Pudlo, N.A.; Wu, M.; McNulty, N.P.; Abbott, D.W.; Henrissat, B.; Gilbert, H.J.; Bolam, D.N.; et al. Recognition and degradation of plant cell wall polysaccharides by two human gut symbionts. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1001221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, A.; Briggs, J.A.; Mortimer, J.C.; Tryfona, T.; Terrapon, N.; Lowe, E.C.; Baslé, A.; Morland, C.; Day, A.M.; Zheng, H.; et al. Glycan complexity dictates microbial resource allocation in the large intestine. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7481, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockburn, D.W.; Koropatkin, N.M. Polysaccharide degradation by the intestinal microbiota and its influence on human health and disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3230–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Wang, J.; Guo, Y. Polysaccharides influence human health via microbiota-dependent and -independent pathways. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1030063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makki, K.; Deehan, E.C.; Walter, J.; Bäckhed, F. The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, K.; Martin, J.C.; Marinsek-Logar, R.; Flint, H.J. Degradation and utilization of xylans by the rumen anaerobe Prevotella bryantii (formerly P. ruminicola subsp. brevis) B14. Anaerobe 1997, 3, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapébie, P.; Lombard, V.; Drula, E.; Terrapon, N.; Henrissat, B. Bacteroidetes use thousands of enzyme combinations to break down glycans. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, R.; Saburi, W.; Odaka, R.; Taguchi, H.; Ito, S.; Mori, H.; Matsui, H. Metabolic mechanism of mannan in a ruminal bacterium, Ruminococcus albus, involving two mannoside phosphorylases and cellobiose 2-epimerase: Discovery of a new new carbohydrate phosphorylase, β-1,4-mannooligosaccharide phosphorylase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 42389–42399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P.; Duncan, S.H.; Louis, P.; Forano, E. Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemsworth, G.R.; Déjean, G.; Davies, G.J.; Brumer, H. Learning from microbial strategies for polysaccharide degradation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.C.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Smith, T.J.; Gordon, J.I. Complex glycan catabolism by the human gut microbiota: The Bacteroidetes Sus-like paradigm. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 24673–24677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaoutari, A.E.; Armougom, F.; Gordon, J.I.; Raoult, D.; Henrissat, B. The abundance and variety of carbohydrate-active enzymes in the human gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjana; Tiwari, S.K. Bacteriocin-producing probiotic lactic acid bacteria in controlling dysbiosis of the gut microbiota. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 851140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culp, E.J.; Goodman, A.L. Cross-feeding in the gut microbiome: Ecology and mechanisms. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 485–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Foley, M.H.; Gardill, B.R.; Dejean, G.; Schnizlein, M.; Bahr, C.M.E.; Creagh, L.A.; Petegem, F.V.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Brumer, H. Surface glycan-binding proteins are essential for cereal beta-glucan utilization by the human gut symbiont Bacteroides ovatus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 4319–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Déjean, G.; Tamura, K.; Cabrera, A.; Jain, N.; Pudlo, N.A.; Pereira, G.; Viborg, A.H.; Petegem, F.V.; Martens, E.C.; Brumer, H. Synergy between cell surface glycosidases and glycan-binding proteins dictates the utilization of specific beta(1,3)-glucans by human gut Bacteroides. mBio 2020, 11, e00095-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskin, F.; Lowe, E.C.; Temple, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; Cameron, E.; Pudlo, N.A.; Porter, N.T.; Urs, K.; Thompson, A.J.; Cartmell, A.; et al. Human gut Bacteroidetes can utilize yeast mannan through a selfish mechanism. Nature 2015, 517, 165–169, Erratum in Nature 2015, 520, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, J.M.; Tamura, K.; Déjean, G.; Abbott, D.W.; Brumer, H. Polysaccharide utilization loci: Fueling microbial communities. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199, e00860-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, M.P.; Couto, N.; Karunakaran, E.; Biggs, C.A.; Wright, P.C. Deciphering the unique cellulose degradation mechanism of the ruminal bacterium Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16542, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miron, J.; Morag, E.; Bayer, E.A.; Lamed, R.; Ben-Ghedalia, D. An adhesion-defective mutant of Ruminococcus albus SY3 is impaired in its capability to degrade cellulose. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1998, 84, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirande, C.; Kadlecikova, E.; Matulova, M.; Capek, P.; Bernalier-Donadille, A.; Forano, E.; Béra-Maillet, C. Dietary fibre degradation and fermentation by two xylanolytic bacteria Bacteroides xylanisolvens XB1AT and Roseburia intestinalis XB6B4 from the human intestine. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.H.; Iakiviak, M.; Bauer, S.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Biochemical analyses of multiple endoxylanases from the rumen bacterium Ruminococcus albus 8 and their synergistic activities with accessory hemicellulose-degrading enzymes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5157–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; Lee, K.T.; Baek, J.Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kwon, M.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, M.R.; Ko, H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.S. Isolation and characterization of a novel glycosyl hydrolase family 74 (GH74) cellulase from the black goat rumen metagenomic library. Folia Microbiol. 2017, 62, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Zhou, S.; O’Hair, J.; Nasr, K.A.; Ropelewski, A.; Li, H. Exploring the microbial diversity and characterization of cellulase and hemicellulase genes in goat rumen: A metagenomic approach. BMC Biotechnol. 2023, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorio, M.G.; Pardue, E.J.; Scott, N.E.; Feldman, M.F. Human gut bacteria tailor extracellular vesicle cargo for the breakdown of diet- and host-derived glycans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2306314120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Hatem, A.; Catalyurek, U.V.; Morrison, M.; Yu, Z. Metagenomic insights into the carbohydrate-active enzymes carried by the microorganisms adhering to solid digesta in the rumen of cows. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Summanen, P.H.; Komoriya, T.; Finegold, S.M. In vitro study of the prebiotic xylooligosaccharide (XOS) on the growth of Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactobacillus spp. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 919–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, H.P.; Motherway, M.O.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; Stanton, C.; Paul Ross, R.; Brulc, J.; Menon, R.; O’Toole, P.W.; Sinderen, D.V. Carbohydrate catabolic diversity of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli of human origin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 203, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guergoletto, K.B.; Magnani, M.; Martin, J.S.; Andrade, C.G.T.D.J.; Garcia, S. Survival of Lactobacillus casei (LC-1) adhered to prebiotic vegetal fibers. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. 2010, 11, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michida, H.; Tamalampudi, S.; Pandiella, S.S.; Webb, C.; Fukuda, H.; Kondo, A. Effect of cereal extracts and cereal fiber on viability of Lactobacillus plantarum under gastrointestinal tract conditions. Biochem. Eng. J. 2006, 28, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, X.; Luo, H.; Huang, H.; Su, X. Identification of WxL and S-Layer proteins from Lactobacillus brevis with the ability to bind cellulose and xylan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Nambu, M.; Katakura, Y.; Yamasaki-Yashiki, S. Adhesion mechanisms of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis JCM 10602 to dietary fiber. Biosci. Microbiota Food Health 2020, 40, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, P.L.; Gorbach, S.L.; Goldin, B.R. Survival of lactic acid bacteria in the human stomach and adhesion to intestinal cells. J. Dairy Sci. 1987, 70, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.R.; Thomas, D.; Alger, N.; Ghavidel, A.; Inglis, G.D.; Abbott, D.W. SACCHARIS: An automated pipeline to streamline discovery of carbohydrate active enzyme activities within polyspecific families and de novo sequence datasets. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, E.A.; Shimon, L.J.; Shoham, Y.; Lamed, R. Cellulosomes—Structure and ultrastructure. J. Struct. Biol. 1998, 124, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataeva, I.A.; Seidel, R.D.; Shah, A.; West, L.T.; Li, X.; Ljungdahl, L.G. The fibronectin type 3-like repeat from the Clostridium thermocellum cellobiohydrolase CbhA promotes hydrolysis of cellulose by modifying its surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4292–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.L.; Hart, W.S.; Lunin, V.V.; Alahuhta, M.; Bomble, Y.J.; Himmel, M.E.; Blumer-Schuette, S.E.; Adams, M.W.W.; Kelly, R.M. Comparative biochemical and structural analysis of novel cellulose binding proteins (Tāpirins) from extremely thermophilic Caldicellulosiruptor species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01983-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuello, C.; Foulon, L.; Chabbert, B.; Aguié-Béghin, V.; Molinari, M. Atomic force microscopy reveals how relative humidity impacts the Young’s modulus of lignocellulosic polymers and their adhesion with cellulose nanocrystals at the nanoscale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 147, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, T.; Pambu, A.L.; Higashimura, Y.; Nakano, M.; Nishiuchi, T. Dietary bacterial cellulose modulates gut microbiota and increases bile acid excretion in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Food Hydrocoll. Health 2025, 7, 100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgrén, G.; Palva, I.; Pakkanen, R.; Lounatmaa, K.; Palva, A. S-layer protein gene of Lactobacillus brevis: Cloning by polymerase chain reaction and determination of the nucleotide sequence. J. Bacteriol. 1992, 174, 7419–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Agarwal, V.; Dodd, D.; Bae, B.; Mackie, R.I.; Nair, S.K.; Cann, I.K.O. Mutational insights into the roles of amino acid residues in ligand binding for two closely related family 16 carbohydrate binding modules. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 34665–34676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaklai, N.; Garlick, R.L.; Bunn, H.F. Nonenzymatic glycosylation of human serum albumin alters its conformation and function. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 3812–3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, R.; Bahrami, H.; Zahedi, M.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A.; Sattarahmady, N. A theoretical elucidation of glucose interaction with HSA’s domains. J. Biomol. Stuct. Dyn. 2010, 28, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Fu, R.; Huang, Y.; Lu, J.; Xie, X.; Xue, Z.; Chen, M.; Wu, X.; Yue, H.; Mai, H. Influence and mechanism of NaOH concentration on the dissolution of cellulose and extraction of CNF in alkaline solvents at 15 °C. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 353, 123265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitch, C.A.; Platzer, G.; Okon, M.; Garcia-Moreno, B.E.; McIntosh, L.P. Arginine: Its pKa value revisited. Protein Sci. 2015, 24, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neil, M.J. The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals; Merck & Co., Inc.: Rahway, NJ, USA, 2006; p. 977. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, J.M.D.; Lourenço, M.; Gordo, I. Horizontal gene transfer among host-associated microbes. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Selle, K.; O’Flaherty, S.; Goh, Y.J.; Klaenhammer, T. Identification of extracellular surface-layer associated proteins in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Microbiology 2013, 159, 2269–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynönen, U.; Palva, A. Lactobacillus surface layer proteins: Structure, function and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 5225–5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.F.; Palomino, M.M.; Cutine, A.M.; Modenutti, C.P.; Porto, D.A.F.D.; Allievi, M.C.; Zanini, S.H.; Mariño, K.V.; Barquero, A.A.; Ruzal, S.M. Exploring lectin-like activity of the S-layer protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 4839–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smit, E.; Oling, F.; Demel, R.; Martinez, B.; Pouwels, P.H. The S-layer protein of Lactobacillus acidophilus ATCC 4356: Identification and characterisation of domains responsible for S-protein assembly and cell wall binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, B.; Ohene-Adjei, S.; Kocherginskaya, S.; Mackie, R.I.; Spies, M.A.; Cann, I.K.O.; Nair, S.K. Molecular basis for the selectivity and specificity of ligand recognition by the family 16 carbohydrate-binding modules from thermoanaerobacterium polysaccharolyticum ManA. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 12415–12425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khangwal, I.; Skariyachan, S.; Uttarkar, A.; Muddebihalkar, A.G.; Niranjan, V.; Shukla, P. Understanding the xylooligosaccharides utilization mechanism of Lactobacillus brevis and Bifidobacterium adolescentis: Proteins involved and their conformational stabilities for effectual binding. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejby, M.; Guskov, A.; Pichler, M.J.; Zanten, G.C.; Schoof, E.; Saburi, W.; Slotboom, D.J.; Hachem, M.A. Two binding proteins of the ABC transporter that confers growth of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis ATCC27673 on β-mannan possess distinct manno-oligosaccharide-binding profiles. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, M.; Martens, E.C.; Simsek, S. How fine structural differences of xylooligosaccharides and arabinoxylooligosaccharides regulate differential growth of Bacteroides species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8398–8405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leschonski, K.P.; Mortensen, M.S.; Hansen, L.B.S.; Krogh, K.B.R.M.; Kabel, M.A.; Laursen, M.F. Structure-dependent stimulation of gut bacteria by arabinoxylo-oligosaccharides (AXOS): A review. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2430419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotta, M.A. Utilization of xylooligosaccharides by selected ruminal bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 3557–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, H.; Yamashita, T.; Morioka, R.; Ohmori, H. Extracellular secretion of noncatalytic plant cell wall-binding proteins by the cellulolytic thermophile Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 3784–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Biochemical and domain analyses of FSUAxe6B, a modular acetyl xylan esterase, identify a unique carbohydrate binding module in Fibrobacter succinogenes S85. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Mackie, R.I.; Cann, I.K.O. Biochemical and mutational analyses of a multidomain cellulase/mannanase from Caldicellulosiruptor bescii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2230–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanier, C.; Bueren, A.L.V.; Dumon, C.; Flint, J.E.; Correia, M.A.; Prates, J.A.; Firbank, S.J.; Lewis, R.J.; Grondin, G.G.; Ghinet, M.G.; et al. Evidence that family 35 carbohydrate binding modules display conserved specificity but divergent function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3065–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, C.M.; Bassler, B.L. Quorum sensing: Cell-to-cell communication in bacteria—Annual review of cell and developmental biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 319–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, S.; Liu, L.; Wei, C. Quorum sensing-mediated microbial interactions: Mechanisms, applications, challenges and perspectives. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 273, 127414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åvall-Jääskeläinen, S.; Hynönen, U.; Ilk, N.; Pum, D.; Sleytr, U.B.; Palva, A. Identification and characterization of domains responsible for self-assembly and cell wall binding of the surface layer protein of Lactobacillus brevis ATCC 8287. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bhalla, N. Moonlighting Proteins. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020, 54, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Hao, Z.; Sun, X.; Qin, L.; Zhao, T.; Liu, W.; Luo, H.; Yao, B.; Su, X. A versatile system for fast screening and isolation of Trichoderma reesei cellulase hyperproducers based on DsRed and fluorescence-assisted cell sorting. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, J.; Shi, P.; Ji, W.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, B.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, W. The use of T-DNA insertional mutagenesis to improve cellulase production by the thermophilic fungus Humicola insolens Y1. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, D.G. Enzymatic assembly of overlapping DNA fragments. Methods Enzym. Enzymol. 2011, 498, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voziyan, P.A.; Khalifah, R.G.; Thibaudeau, C.; Yildiz, A.; Jacob, J.; Serianni, A.S.; Hudson, B.G. Modification of proteins in vitro by physiological levels of glucose: Pyridoxamine inhibits conversion of Amadori intermediate to advanced glycation end-products through binding of redox metal ions. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 46616–46624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antikainen, J.; Anton, L.; Sillanpää, J.; Korhonen, T.K. Domains in the S-layer protein CbsA of Lactobacillus crispatus involved in adherence to collagens, laminin and lipoteichoic acids and in self-assembly. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 46, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hymes, J.P.; Johnson, B.R.; Barrangou, R.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Functional analysis of an S-layer-associated fibronectin-binding protein in Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2676–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.R.; Hymes, J.; Sanozky-Dawes, R.; Henriksen, E.D.; Barrangou, R.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Conserved S-layer-associated proteins revealed by exoproteomic survey of S-layer-forming Lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 82, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, C.; O’Flaherty, S.; Goh, Y.J.; Barrangou, R. Investigating the effect of growth phase on the surface-layer associated proteome of Lactobacillus acidophilus using quantitative proteomics. Front Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Gan, J.; Su, M.; Xiong, B.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, T.; Zeng, X.; Wu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Pan, D.; et al. Identification and characterization of domains responsible for cell wall binding, self-assembly, and adhesion of S-layer protein from Lactobacillus acidophilus CICC 6074. J Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 12982–12989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; He, L.; Sun, Z. Bioinformatic survey of S-layer proteins in Bifidobacteria. Comput. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 8, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzeo, M.F.; Reale, A.; Renzo, T.D.; Siciliano, R.A. Surface layer protein pattern of Levilactobacillus brevis strains investigated by proteomics. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podlesny, M.; Jarocki, P.; Komon, E.; Glibowska, A.; Targonski, Z. LC-MS/MS analysis of surface layer proteins as a useful method for the identification of lactobacilli from the Lactobacillus acidophilus group. J Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 21, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.M.; Anderson, D.E.; Bernstein, H.D. Analysis of the outer membrane proteome and secretome of Bacteroides fragilis reveals a multiplicity of secretion mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Anaya, C.; Lewis, J.P. Outer membrane proteome of Prevotella intermedia 17: Identification of thioredoxin and iron-repressible hemin uptake loci. Proteomics 2007, 7, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Ge, J.; Yang, D.; Guo, K.; Wang, Y.; Luo, H.; Huang, H.; Su, X. Nonspecific Binding of a Putative S-Layer Protein to Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides—Implication for Growth Competence of Lactobacillus brevis in the Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311612

Hao Z, Zhang W, Ge J, Yang D, Guo K, Wang Y, Luo H, Huang H, Su X. Nonspecific Binding of a Putative S-Layer Protein to Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides—Implication for Growth Competence of Lactobacillus brevis in the Gut Microbiota. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311612

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Zhenzhen, Wenjing Zhang, Jianzhong Ge, Daoxin Yang, Kairui Guo, Yuan Wang, Huiying Luo, Huoqing Huang, and Xiaoyun Su. 2025. "Nonspecific Binding of a Putative S-Layer Protein to Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides—Implication for Growth Competence of Lactobacillus brevis in the Gut Microbiota" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311612

APA StyleHao, Z., Zhang, W., Ge, J., Yang, D., Guo, K., Wang, Y., Luo, H., Huang, H., & Su, X. (2025). Nonspecific Binding of a Putative S-Layer Protein to Plant Cell Wall Polysaccharides—Implication for Growth Competence of Lactobacillus brevis in the Gut Microbiota. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311612