Lysosome as a Chemical Reactor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Lysosomal Chemical Microenvironment in Cancer

2.1. Acidic pH and Protonation Dynamics

2.2. Redox Conditions and Reactive Species

2.3. Metal Ion Sequestration and Catalysis

2.4. Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Acid Hydrolases as Catalysts

3. Lysosomotropic Drug Accumulation and the “Safe House” Effect

3.1. Lysosomal Drug Metabolism and Activation

3.2. Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization: A Double-Edged Sword

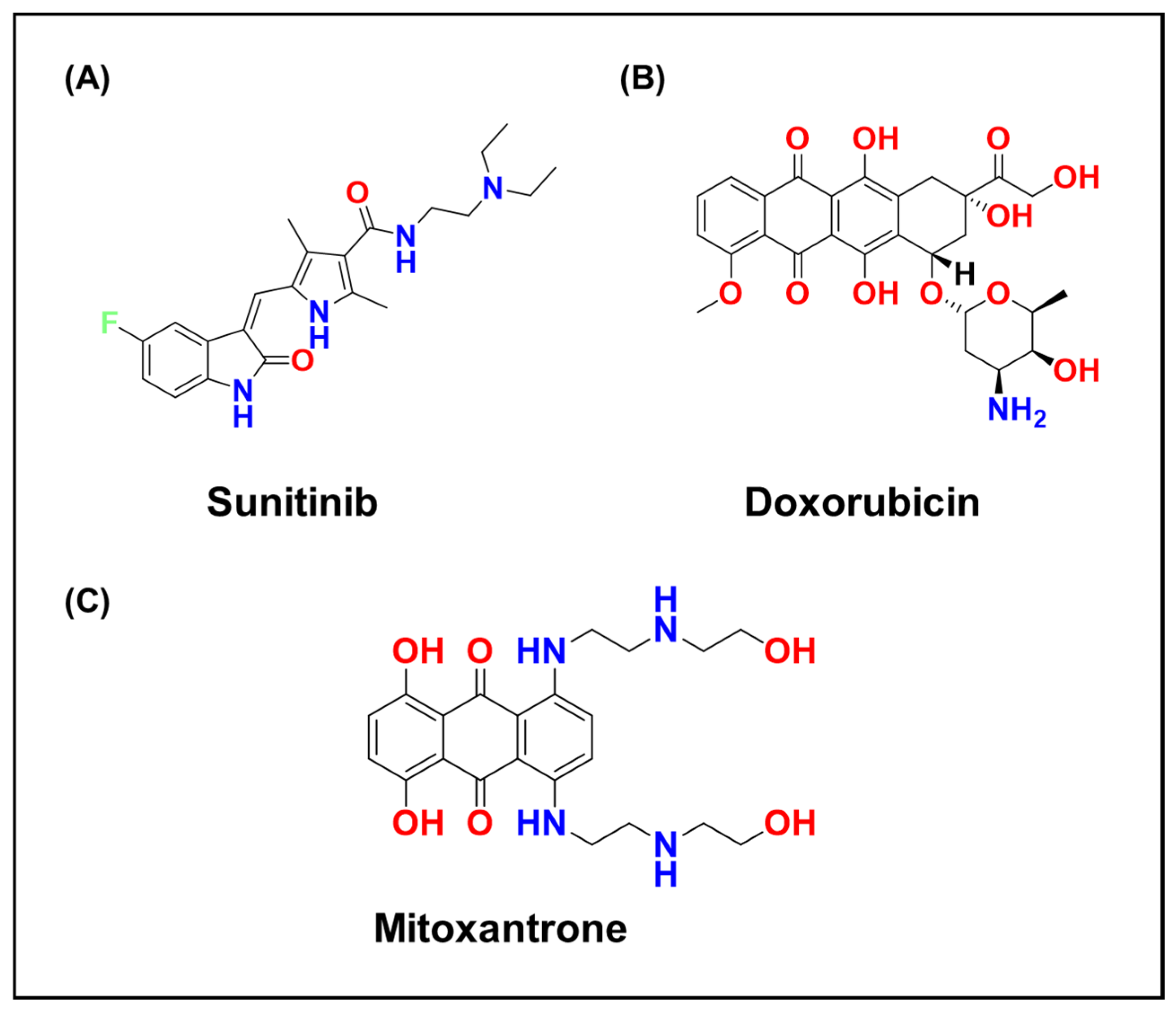

3.3. Lysosomal Inactivation of Drugs and Drug–Drug Interactions

4. Strategies to Exploit Lysosomal Chemistry for Cancer Therapy

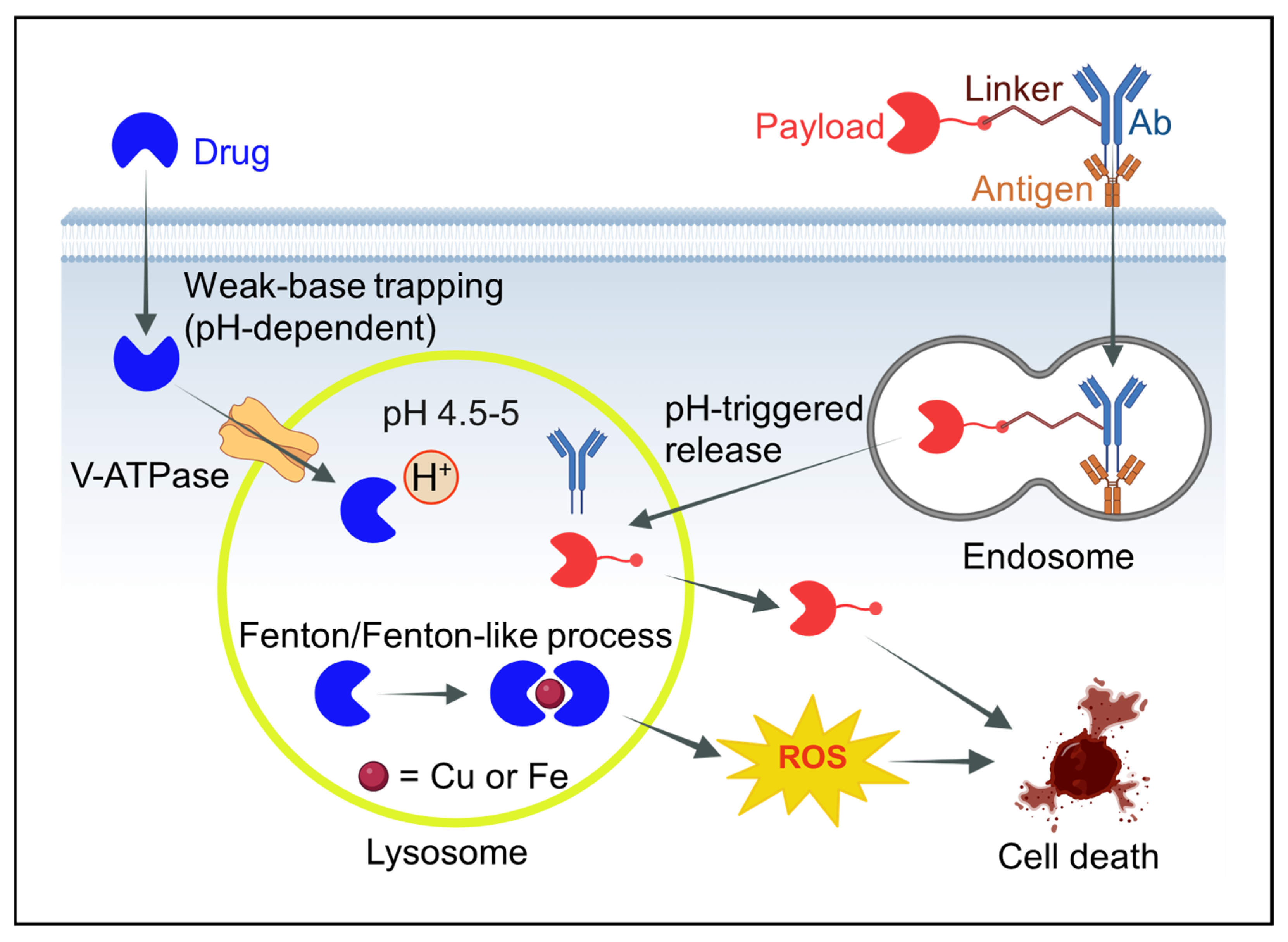

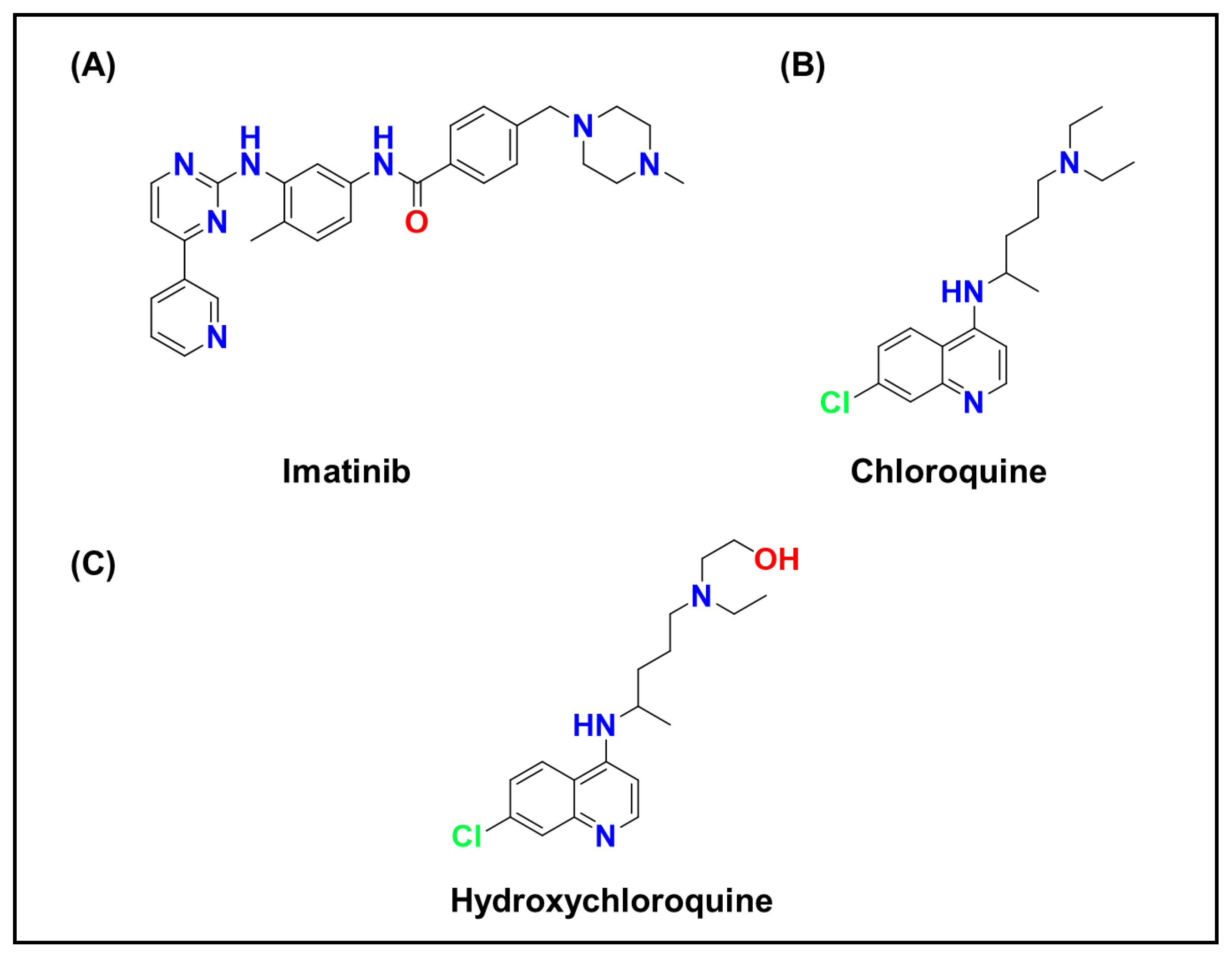

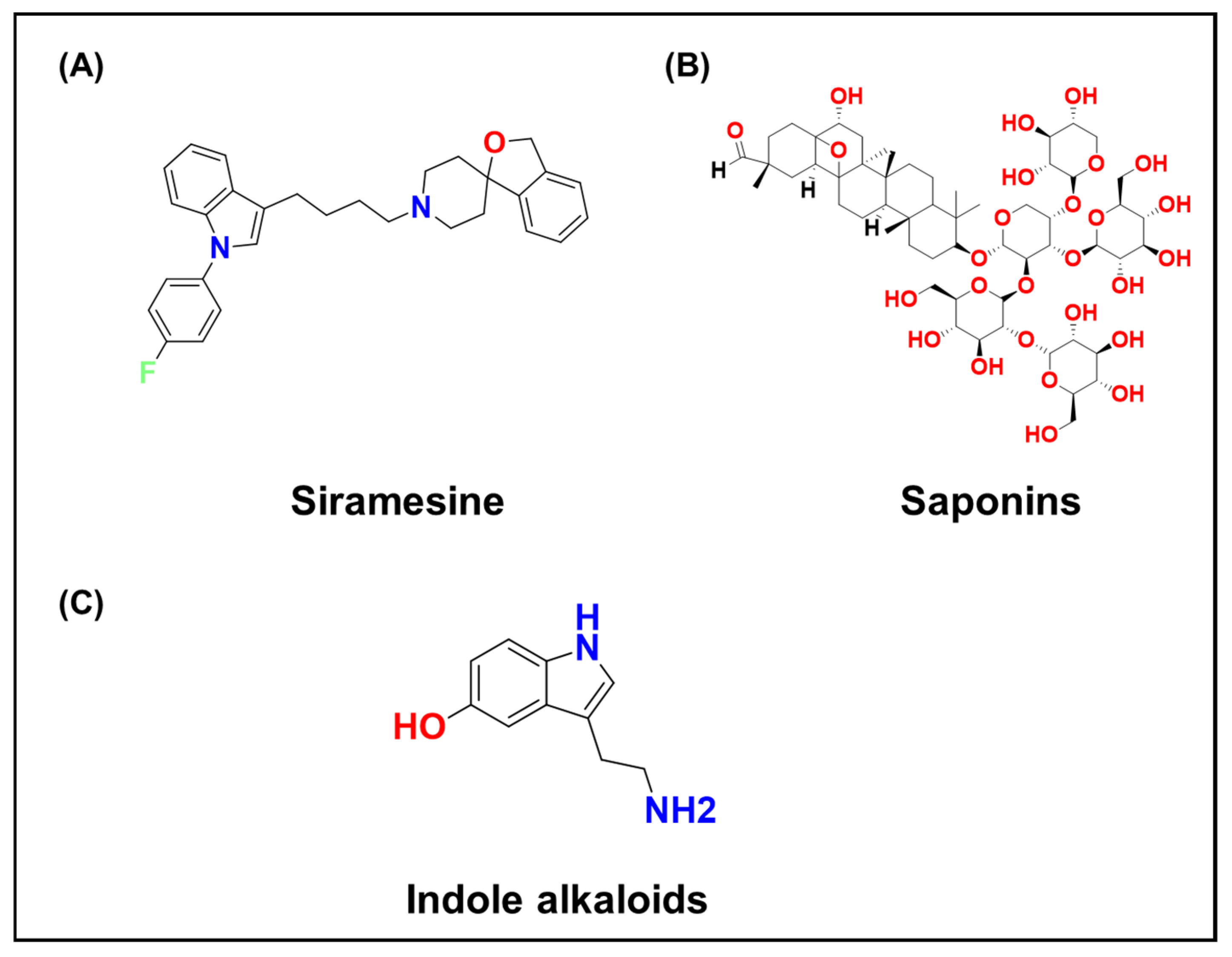

4.1. Weak-Base Trapping as a Targeting Mechanism

4.2. pH-Triggered Release Systems

4.3. Redox-Responsive Drug Release and Action

5. Enzyme-Cleavable Prodrugs and Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

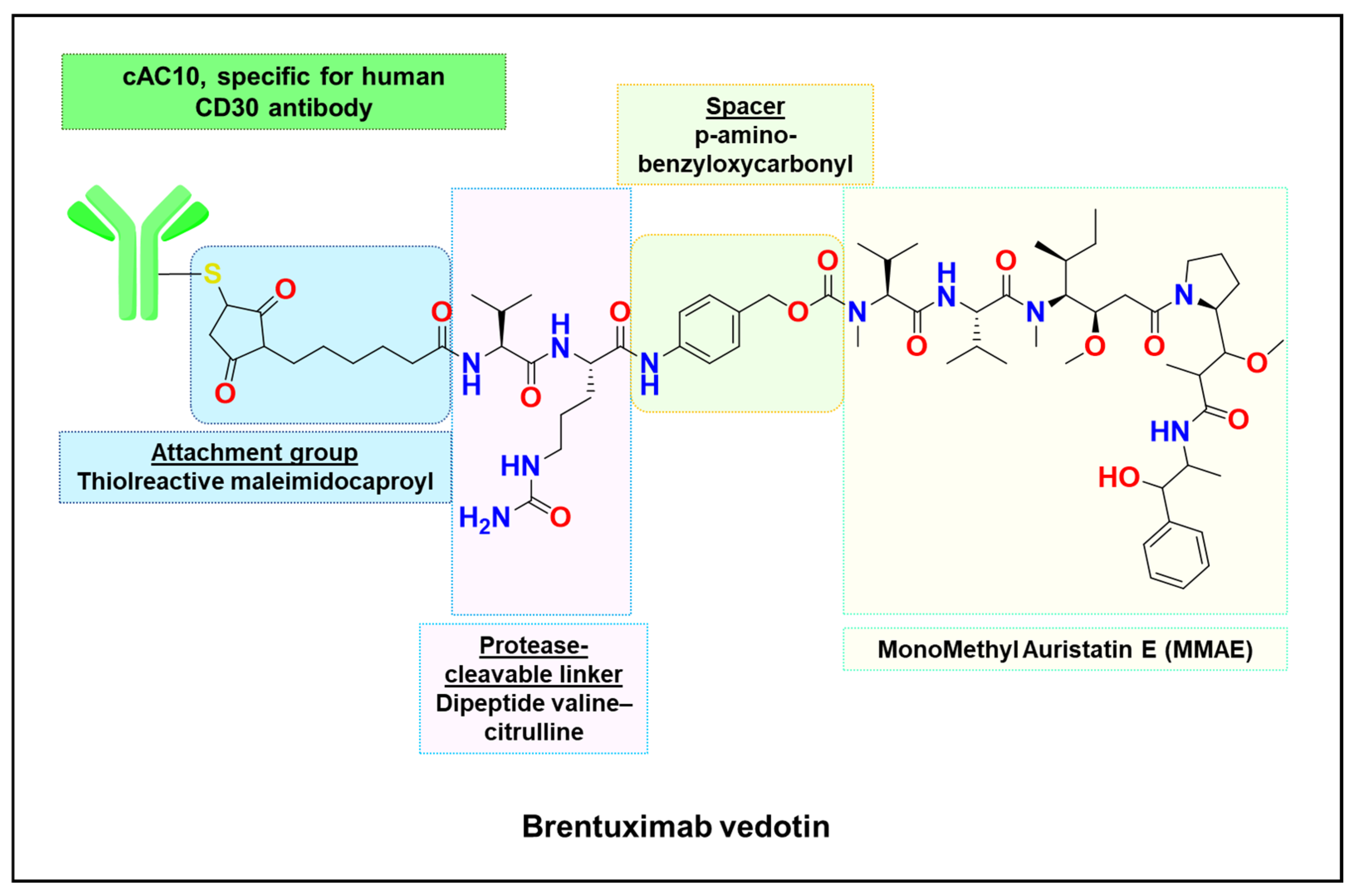

5.1. Antibody–Drug Conjugates

5.2. Peptide- and Polymer–Drug Conjugates: Enzyme-Cleavable Systems and Design Considerations

6. Emerging Concepts in Lysosomal Modulation and Targeted Chimeras

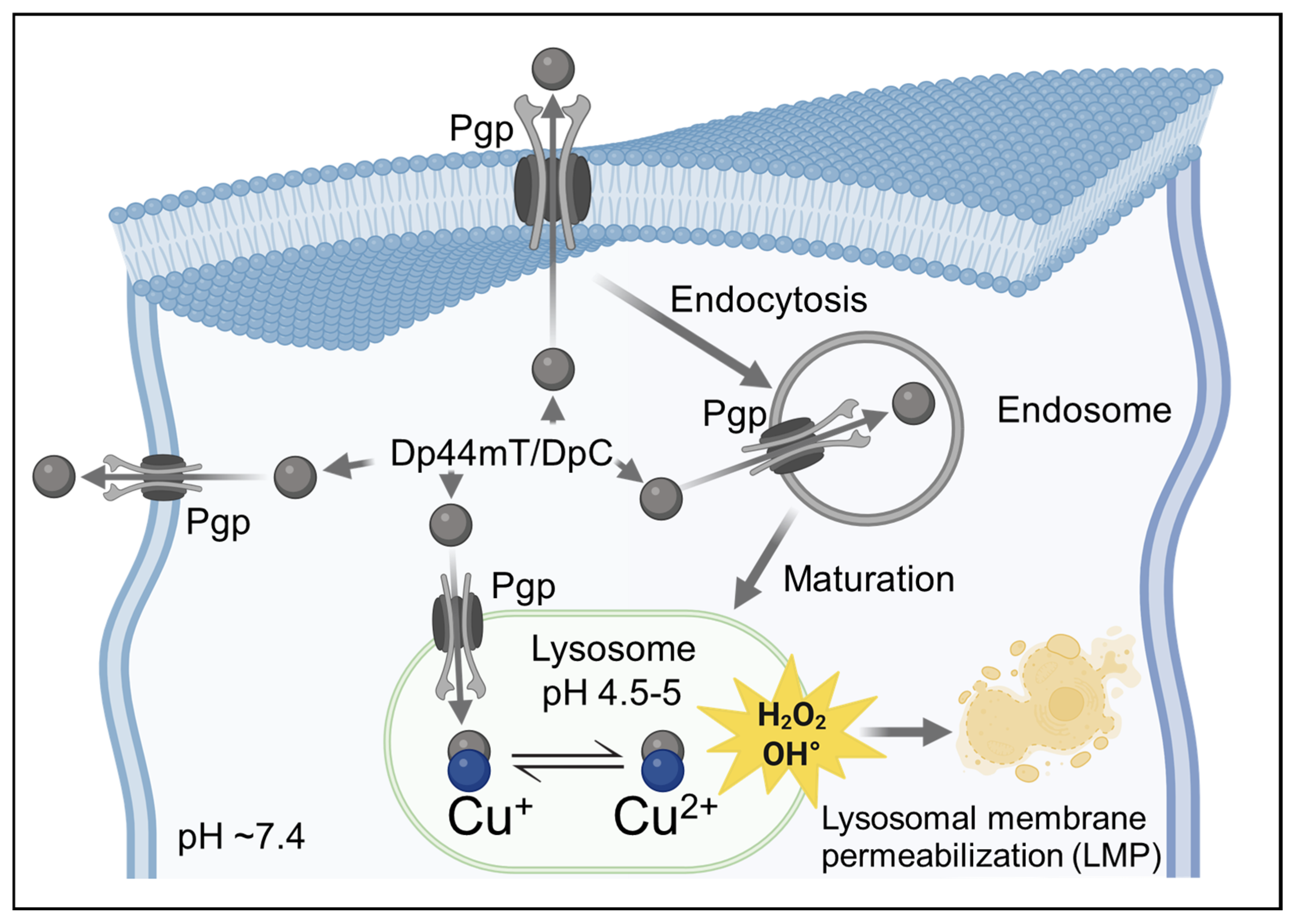

6.1. Overcoming Lysosomal Drug Sequestration and Combination Strategies

6.1.1. Combination Therapy to Release Trapped Drugs

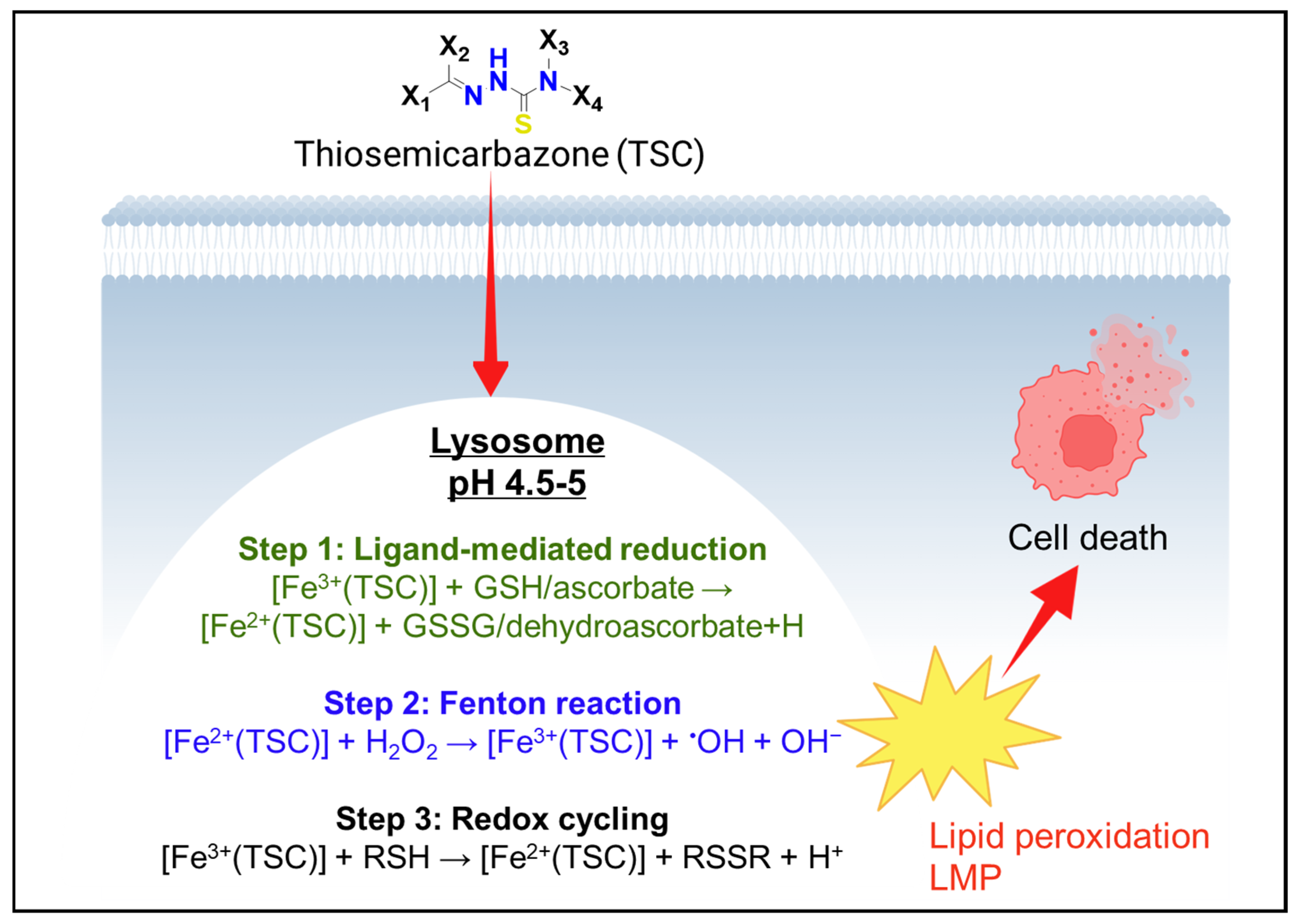

6.1.2. Acridine–Thiosemicarbazone Hybrids: Targeting Lysosomes by Design

6.1.3. Lysosome-Targeted Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapy

6.1.4. Targeting Lysosomal Membrane Proteins

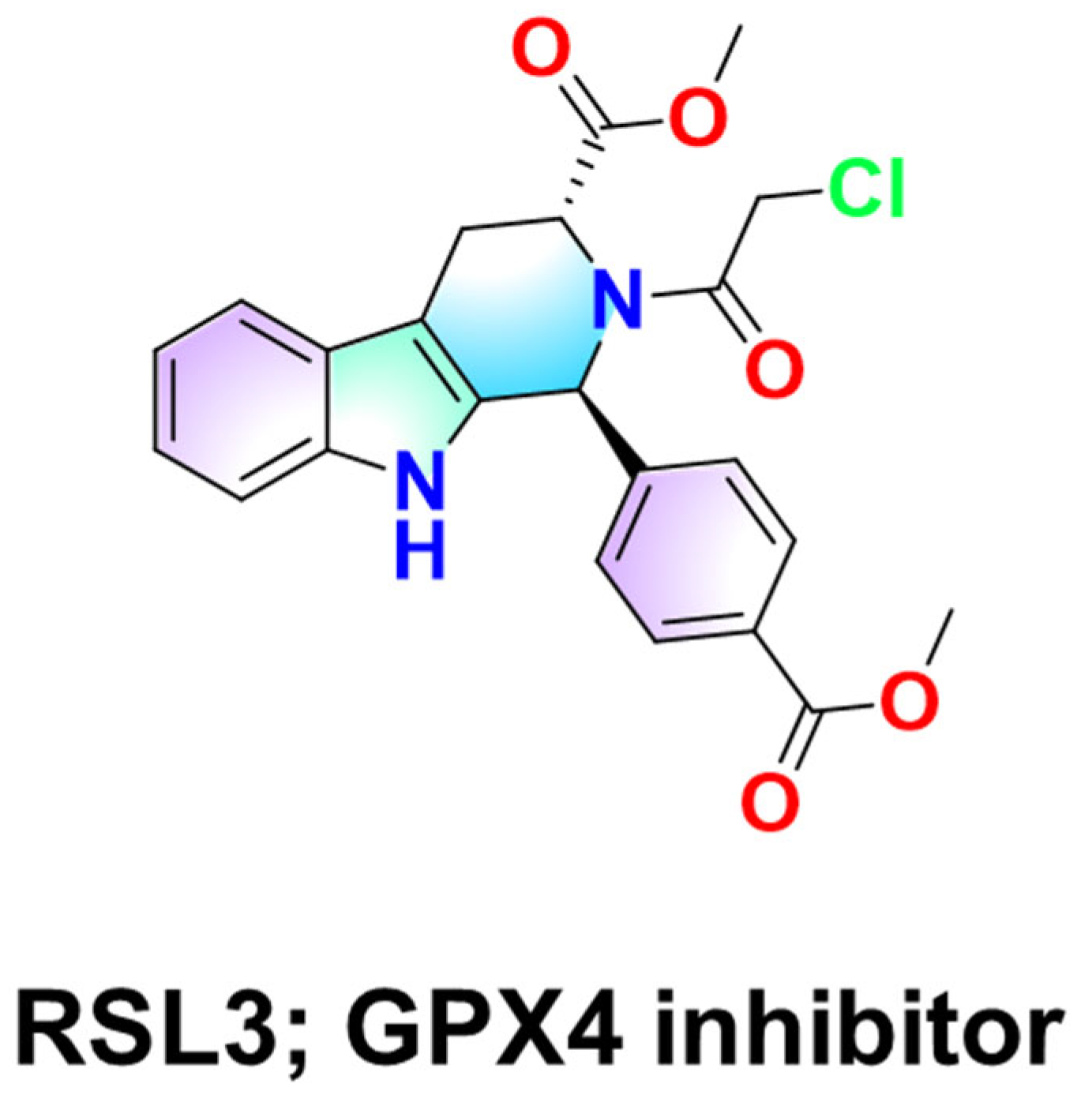

6.1.5. Sensitizing Cells to Ferroptosis via Lysosomal Iron

6.2. Metal-Based Drugs and Lysosomal Redox Mechanisms

6.2.1. Copper Complexes

6.2.2. Gold Compounds

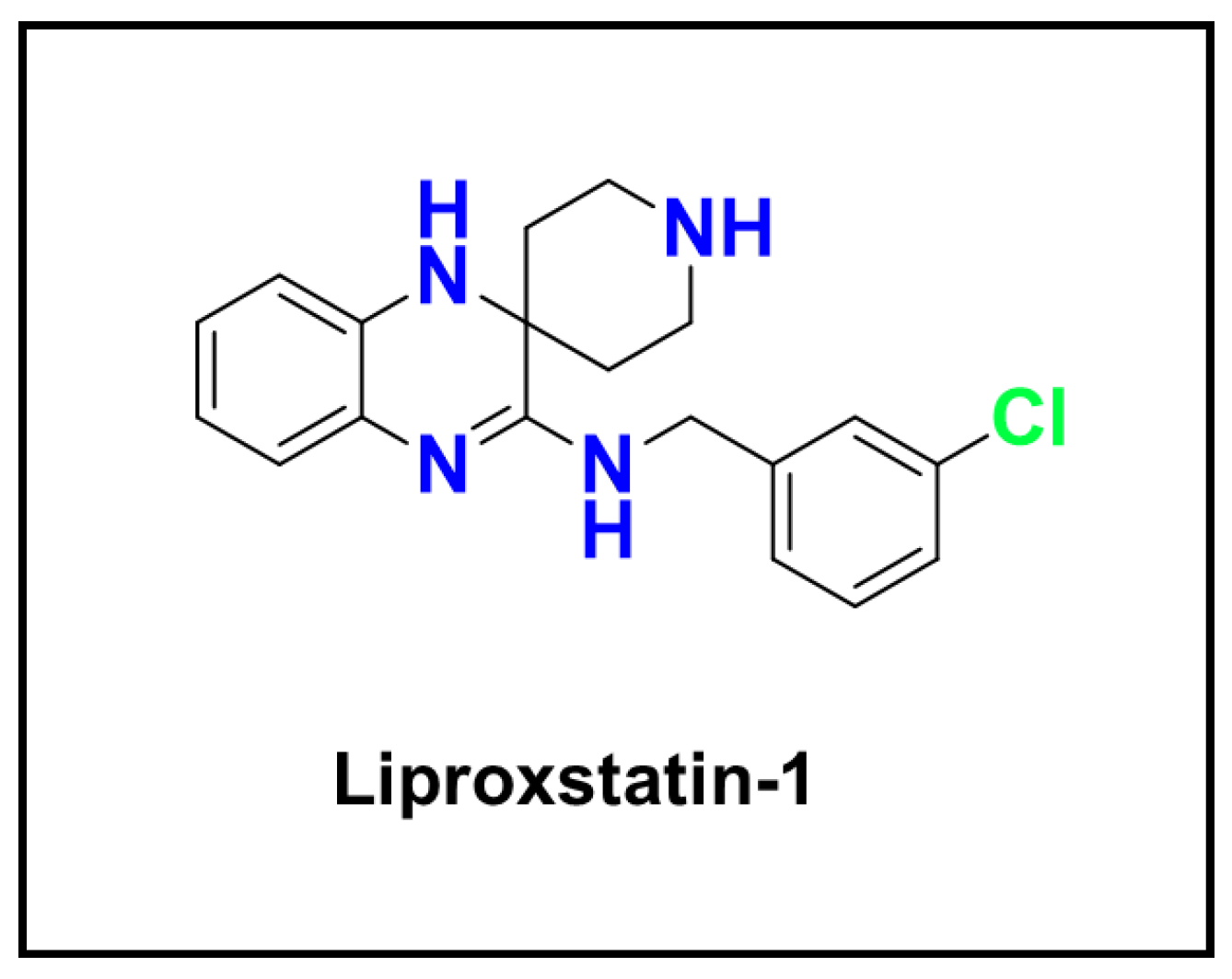

6.2.3. Ferroptosis Inhibitors and Radical-Trapping Antioxidants

6.2.4. Photodynamic Metal Complexes

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Antibody–Drug Conjugate |

| CDT | Chemodynamic Therapy |

| DCF | Dichlorofluorescein |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| DOXIL | Doxorubicin Liposomal Formulation |

| DpC | Di-2-pyridylketone-4-Cyclohexyl-4-Methyl-3-Thiosemicarbazone |

| Dp44mT | Di-2-pyridylketone-4,4-Dimethyl-3-Thiosemicarbazone |

| FDX1 | Ferredoxin 1 |

| FRET | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

| GILT | γ-Interferon-Inducible Lysosomal Thiol Reductase |

| GPX4 | Glutathione Peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| H2DCF-DA | 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HPMA | N-(2-Hydroxypropyl)-Methacrylamide |

| ICP-MS | Inductively Coupled Plasma–Mass Spectrometry |

| LAMP-1 | Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1 |

| LAMP-2 | Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 2 |

| LMP | Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization |

| LYTAC | Lysosome-Targeting Chimera |

| MDR | Multidrug Resistance |

| MMAE | Monomethyl Auristatin E |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 |

| NAT | N-Acridine–Thiosemicarbazone |

| NRF2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| PABC | Para-Aminobenzylcarbamate |

| PDC | Peptide–Drug Conjugate |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| Pgp | P-Glycoprotein |

| PQLC2 | Proline–Glutamine Loop Containing 2 |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RSL3 | RAS-Selective Lethal 3 |

| TFEF | Transcription Factor EB |

| TSC | Thiosemicarbazone |

| Val–Cit | Valine–Citrulline Dipeptide |

| V-ATPase | Vacuolar H+-ATPase Pump |

References

- Xiang, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, M.; Chen, Q.; Long, X.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Nanodrugs Detonate Lysosome Bombs. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 909504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Vooijs, M.A.; Keulers, T.G. Key Mechanisms in Lysosome Stability, Degradation and Repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2025, 45, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matte, U.; Pasqualim, G. Lysosome: The story beyond the storage. J. Inborn Errors Metab. Screen. 2016, 4, 2326409816679431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Griffin, A.; Qiang, Z.; Ren, J. Organelle-targeted therapies: A comprehensive review on system design for enabling precision oncology. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallwitz, L.; Bleibaum, F.; Voss, M.; Schweizer, M.; Spengler, K.; Winter, D.; Zophel, F.; Muller, S.; Lichtenthaler, S.; Damme, M.; et al. Cellular depletion of major cathepsin proteases reveals their concerted activities for lysosomal proteolysis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Duan, D.; Zhao, L. Organelle-Specific Mechanisms in Crosstalk between Apoptosis and Ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2023, 2023, 3400147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Ofengeim, D. A guide to cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Smith, H.; Chen, Y.; Azad, M.G.; Russell, T.M.; Richardson, V.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, D.R. Targeting lysosomes by design: Novel N-acridine thiosemicarbazones that enable direct detection of intracellular drug localization and overcome P-glycoprotein (Pgp)-mediated resistance. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 15109–15124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, N.A.; Richardson, D.R.; Jansson, P.J. A mechanism for overcoming P-glycoprotein-mediated drug resistance: Novel combination therapy that releases stored doxorubicin from lysosomes via lysosomal permeabilization using Dp44mT or DpC. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Chen, J.; Yu, P.; Atherton, M.J.; Gui, J.; Tomar, V.S.; Middleton, J.D.; Sullivan, N.T.; Singhal, S.; George, S.S.; et al. Tumor factors stimulate lysosomal degradation of tumor antigens and undermine their cross-presentation in lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, T.; Hu, X.; Deng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, L.; et al. A dual chemodrug-loaded hyaluronan nanogel for differentiation induction therapy of refractory AML via disrupting lysosomal homeostasis. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eado3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, M.; Silva, T.F.D.; Levin, G.; Machuqueiro, M.; Assaraf, Y.G. The Lysosomotropic Activity of Hydrophobic Weak Base Drugs is Mediated via Their Intercalation into the Lysosomal Membrane. Cells 2020, 9, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahapatra, K.K.; Mishra, S.R.; Behera, B.P.; Patil, S.; Gewirtz, D.A.; Bhutia, S.K. The lysosome as an imperative regulator of autophagy and cell death. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 7435–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, S.; Patil, S.; Klionsky, D.J.; Bhutia, S.K. Lysosome signaling in cell survival and programmed cell death for cellular homeostasis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2023, 238, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, G.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, R.; Qu, J.; Li, W. Survival strategies of cancer cells: The role of macropinocytosis in nutrient acquisition, metabolic reprogramming, and therapeutic targeting. Autophagy 2025, 21, 693–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuesta-Casanovas, L.; Delgado-Martinez, J.; Cornet-Masana, J.M.; Carbo, J.M.; Clement-Demange, L.; Risueno, R.M. Lysosome-mediated chemoresistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Drug Resist. 2022, 5, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, A.-M.; Bach, P.; Jäättelä, M. Targeting cancer lysosomes with good old cationic amphiphilic drugs. In Organelles in Disease; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 107–152. [Google Scholar]

- Geisslinger, F.; Muller, M.; Chao, Y.K.; Grimm, C.; Vollmar, A.M.; Bartel, K. Targeting TPC2 sensitizes acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to chemotherapeutics by impairing lysosomal function. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeda, S.; Kanda, M.; Shimizu, D.; Nakamura, S.; Sawaki, K.; Inokawa, Y.; Hattori, N.; Hayashi, M.; Tanaka, C.; Nakayama, G.; et al. Lysosomal-associated membrane protein family member 5 promotes the metastatic potential of gastric cancer cells. Gastric Cancer 2022, 25, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, B.; Saminathan, A.; Chakraborty, K.; Zajac, M.; Cui, C.; Becker, L.; Krishnan, Y. Tubular lysosomes harbor active ion gradients and poise macrophages for phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2113174118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Xu, W.; Xu, S.; Niu, Q. Impaired V-ATPase leads to increased lysosomal pH, results in disrupted lysosomal degradation and autophagic flux blockage, contributes to fluoride-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 2022, 236, 113500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salto, R.; Giron, M.D.; Paredes, J.M. Genetically encoded red fluorescent pH ratiometric sensor: Application to measuring pH gradient abnormalities in cystic fibrosis cells. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2024, 410, 135673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, W.; Han, Y.; Lee, W.R.; Liou, J.; Jiang, Y. Lysosomal LAMP proteins regulate lysosomal pH by direct inhibition of the TMEM175 channel. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2524–2539.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovejoy, D.B.; Jansson, P.J.; Brunk, U.T.; Wong, J.; Ponka, P.; Richardson, D.R. Antitumor activity of metal-chelating compound Dp44mT is mediated by formation of a redox-active copper complex that accumulates in lysosomes. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 5871–5880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, W.; Noh, M.Y.; Nahm, M.; Kim, Y.S.; Ki, C.S.; Kim, Y.E.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.H. Progranulin haploinsufficiency mediates cytoplasmic TDP-43 aggregation with lysosomal abnormalities in human microglia. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Chen, B.; Xia, H.; Pan, M.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, J.; Yin, Q.; Wan, F.; Yan, Y.; Fu, C.; et al. pH-gated nanoparticles selectively regulate lysosomal function of tumour-associated macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacy, A.E.; Palanimuthu, D.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. Zinc(II)-Thiosemicarbazone Complexes Are Localized to the Lysosomal Compartment Where They Transmetallate with Copper Ions to Induce Cytotoxicity. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4965–4984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anees, P. Quantitative Strategies for Decoding Organelle Ion Dynamics. Chembiochem 2025, 26, e202500557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Yu, M.; Jiang, M.; Gao, Z.; Zheng, D.; Shi, W.; Cheng, D.; Zhao, X. Lysosomal Acidification: A New Perspective on the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Compr. Physiol. 2025, 15, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leray, X.; Hilton, J.K.; Nwangwu, K.; Becerril, A.; Mikusevic, V.; Fitzgerald, G.; Amin, A.; Weston, M.R.; Mindell, J.A. Tonic inhibition of the chloride/proton antiporter ClC-7 by PI(3,5)P2 is crucial for lysosomal pH maintenance. Elife 2022, 11, e74136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, R.; Barth, A.; Wong, H.; Marik, J.; Shen, J.; Lade, J.; Grove, K.; Durk, M.R.; Parrott, N.; Rudewicz, P.J.; et al. Design and Measurement of Drug Tissue Concentration Asymmetry and Tissue Exposure-Effect (Tissue PK-PD) Evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8713–8734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, A.F.; Merkulova, M.; Brown, D. The H(+)-ATPase (V-ATPase): From proton pump to signaling complex in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C392–C414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settembre, C.; Perera, R.M. Lysosomes as coordinators of cellular catabolism, metabolic signalling and organ physiology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinn, J.; Kwon, N.; Lee, S.A.; Lee, Y. Smart pH-responsive nanomedicines for disease therapy. J. Pharm. Investig. 2022, 52, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaohua, L.; Miao, X.; Dou, L. Crosstalk of physiological pH and chemical pKa under the umbrella of physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2021, 17, 1103–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Qu, Y.; Tang, F.; Wang, H.; Ding, A.; Li, L. Advances in Small-Molecule Fluorescent pH Probes for Monitoring Mitophagy. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2024, 2, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barral, D.C.; Staiano, L.; Guimas Almeida, C.; Cutler, D.F.; Eden, E.R.; Futter, C.E.; Galione, A.; Marques, A.R.A.; Medina, D.L.; Napolitano, G.; et al. Current methods to analyze lysosome morphology, positioning, motility and function. Traffic 2022, 23, 238–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirbhate, E.; Singh, V.; Mishra, A.; Jahoriya, V.; Veerasamy, R.; Tiwari, A.K.; Rajak, H. Targeting Lysosomes: A Strategy Against Chemoresistance in Cancer. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 1449–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.L.; Rowson-Hodel, A.; Wheeler, M.R.; Hu, M.; Free, S.; Carraway, K.L., III. Engaging the lysosome and lysosome-dependent cell death in cancer. In Breast Cancer; Exon Publications: Brisbane, AU, USA, 2022; pp. 195–230. [Google Scholar]

- Gronkowska, K.; Michlewska, S.; Robaszkiewicz, A. Activity of Lysosomal ABCC3, ABCC5 and ABCC10 is Responsible for Lysosomal Sequestration of Doxorubicin and Paclitaxel-Oregongreen488 in Paclitaxel-Resistant Cancer Cell Lines. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 57, 360–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elblova, P.; Anthi, J.; Liu, M.; Lunova, M.; Jirsa, M.; Stephanopoulos, N.; Lunov, O. DNA Nanostructures for Rational Regulation of Cellular Organelles. JACS Au 2025, 5, 1591–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.V.; Reichel, A.; Liu, X.; Fricker, G.; Lienau, P. Extension of the Mechanistic Tissue Distribution Model of Rodgers and Rowland by Systematic Incorporation of Lysosomal Trapping: Impact on Unbound Partition Coefficient and Volume of Distribution Predictions in the Rat. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2021, 49, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.Y.; Schouten, W.M.; Mavoko, H.M.; Tshiongo, J.K.; Yobi, D.M.; Kabasele, F.A.; Kasereka, G.; Maketa, V.; Sevene, E.; Vala, A.; et al. Importance of Lysosomal Trapping and Plasmodium Parasite Infection on the Pharmacokinetics of Pyronaridine: A Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model-Based Study. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Sbirkov, Y.; Kazakova, M.; Sarafian, V. Lysosomes and LAMPs as Autophagy Drivers of Drug Resistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Qian, L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, F.; Zheng, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Yuan, H.; Lou, H. Targeting of VPS18 by the lysosomotropic agent RDN reverses TFE3-mediated drug resistance. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, J.; Liu, H.; Guan, L.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, H.; Peng, L.; Men, X. Ajugol enhances TFEB-mediated lysosome biogenesis and lipophagy to alleviate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 174, 105964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauck, A.V.; Komforth, P.; Erlenbusch, J.; Stickdorn, J.; Radacki, K.; Braunschweig, H.; Besenius, P.; Van Herck, S.; Nuhn, L. Aliphatic polycarbonates with acid degradable ketal side groups as multi-pH-responsive immunodrug nanocarriers. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Pandey, T. Mechanistic understanding of pH as a driving force in cancer therapeutics. J. Mater. Chem. B 2025, 13, 2640–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parshad, B.; Arora, S.; Singh, B.; Pan, Y.; Tang, J.; Hu, Z.; Patra, H.K. Towards precision medicine using biochemically triggered cleavable conjugation. Commun. Chem. 2025, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesundara, Y.H.; Howlett, T.S.; Kumari, S.; Gassensmith, J.J. The Promise and Potential of Metal-Organic Frameworks and Covalent Organic Frameworks in Vaccine Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3013–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsel, H.; Winkelmann, G. Iron chelation and siderophores. In Transition Metals in Microbial Metabolism; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, K.; Li, M.; Luo, Z. A protein-based cGAS-STING nanoagonist enhances T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune responses. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Khalique, A.; Sun, Z.; Chen, R.; Wei, J.; Li, H.; et al. Nanozyme-Powered Giant Unilamellar Vesicles for Mimicry and Modulation of Intracellular Oxidative Stress. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 21087–21096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Sebag, S.C.; Qian, Q.; Yang, L. Lysosomal physiology and pancreatic lysosomal stress in diabetes mellitus. eGastroenterology 2024, 2, e100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, A.; Kurz, T. Lysosomal iron, iron chelation, and cell death. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 888–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Eaton, J.W.; Brunk, U.T. Redox activity within the lysosomal compartment: Implications for aging and apoptosis. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, R.; Muller, S.; Colombeau, L.; Solier, S.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Caneque, T. Metal Ion Signaling in Biomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2025, 125, 660–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, D.E. Hydrogen peroxide produced by mitochondrial monoamine oxidase catalysis: Biological implications. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, R.K.; Lee, J.N.; Maharjan, Y.; Park, C.; Choe, S.K.; Ho, Y.S.; Kwon, H.M.; Park, R. Catalase-deficient mice induce aging faster through lysosomal dysfunction. Cell Commun. Signal. 2022, 20, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, G.; Kim, C.; Cho, U.M.; Hwang, E.T.; Hwang, H.S.; Min, J. Melanin-Decolorizing Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes, Glutathione Peroxidase, Thiol Peroxidase, and Catalase. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoryk, O.; Horila, M. Oxidative stress and disruption of the antioxidant defense system as triggers of diseases. Regul. Mech. Biosyst. 2023, 14, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Boudagh, G.; Eskelinen, E.L.; Klionsky, D.J.; Malek, S.N. Follicular lymphoma-associated mutations in the V-ATPase chaperone VMA21 activate autophagy creating a targetable dependency. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1982–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alder, A.; Sanchez, C.P.; Russell, M.R.G.; Collinson, L.M.; Lanzer, M.; Blackman, M.J.; Gilberger, T.W.; Matz, J.M. The role of Plasmodium V-ATPase in vacuolar physiology and antimalarial drug uptake. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2306420120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chakrabarty, R.; Paira, P. Harnessing Photodynamic Therapy for Programmed Cell Death: The Central Role and Contributions of Metal Complexes as Next Generation Photosensitizers. RSC Med. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewanchuk, B.W.; Yates, R.M. The phagosome and redox control of antigen processing. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 125, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poreba, M. Protease-activated prodrugs: Strategies, challenges, and future directions. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 1936–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wolter, T.; Hu, Q. Intracellular metal ion-based chemistry for programmed cell death. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 1552–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, L.C.; Lo, K.K. Leveraging the Photofunctions of Transition Metal Complexes for the Design of Innovative Phototherapeutics. Small Methods 2024, 8, e2400563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ma, Q.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Guo, Q.; Tao, L.; Shen, X. Boosting ROS-Mediated Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization for Cancer Ferroptosis Therapy. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2023, 12, e2202150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Jin, M.; Yang, K.; Chen, B.; Xiong, M.; Li, X.; Cao, G. Fenton/Fenton-like metal-based nanomaterials combine with oxidase for synergistic tumor therapy. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, M.; Liu, S.B. Research progress on morphology and mechanism of programmed cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. Fe3+ reducing power as the most common assay for understanding the biological functions of antioxidants. Processes 2025, 13, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwozdzinski, K.; Pieniazek, A.; Gwozdzinski, L. Reactive Oxygen Species and Their Involvement in Red Blood Cell Damage in Chronic Kidney Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6639199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, E.; Ritacca, A.G.; Hager, S.; Schueffl, H.; Vileno, B.; El Khoury, Y.; Hellwig, P.; Kowol, C.R.; Heffeter, P.; Sicilia, E.; et al. Copper-Catalyzed Glutathione Oxidation is Accelerated by the Anticancer Thiosemicarbazone Dp44mT and Further Boosted at Lower pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14758–14768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Redox-manipulating nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery: A systematic review. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; E, J.; Zhao, X.; Xie, R.; Wu, J.; Feng, L.; Ding, H.; He, F.; Yang, P. Hetero-Trimetallic Atom Catalysts Enable Targeted ROS Generation and Redox Signaling for Intensive Apoptosis and Ferroptosis. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2417198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Fu, H.; Lin, J.; Zhao, M.; Chen, C.; Liao, H.; Duan, Y. Harnessing the Biological Responses Induced by Nanomaterials for Enhanced Cancer Therapy. Aggregate 2025, 6, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Guo, Y.; Wu, F.G. Chemodynamic Therapy via Fenton and Fenton-Like Nanomaterials: Strategies and Recent Advances. Small 2022, 18, e2103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: Outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boya, P.; Kroemer, G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6434–6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulovic, M.; Yang, C.; Stenmark, H. Lysosomal membrane homeostasis and its importance in physiology and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caneque, T.; Baron, L.; Muller, S.; Carmona, A.; Colombeau, L.; Versini, A.; Solier, S.; Gaillet, C.; Sindikubwabo, F.; Sampaio, J.L.; et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature 2025, 642, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, C.; Jiang, J.; Li, Y.; Peng, Z. ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death outcome: Mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadian, K. Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and coenzyme Q10 cooperatively suppress ferroptosis. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Cai, L.; Deng, K.; Zhou, C.; Qiu, G.; Lian, J.; Xu, Q. FSP1 reduces exogenous coenzyme Q10 and inhibits ferroptosis to alleviate intestinal ischemia–reperfusion injury. J. Adv. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wang, T.; Yang, R.; Zhu, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Guo, Y.; He, Y. α-Tocopherol ameliorates allergic airway inflammation by regulating ILC2 ferroptosis in an LKB1-dependent manner. Mol. Ther. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lou, H.; Ou, Z.; Liu, J.; Duan, W.; Wang, H.; Ge, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. GPX4 and vitamin E cooperatively protect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saimoto, Y.; Kusakabe, D.; Morimoto, K.; Matsuoka, Y.; Kozakura, E.; Kato, N.; Tsunematsu, K.; Umeno, T.; Kiyotani, T.; Matsumoto, S.; et al. Lysosomal lipid peroxidation contributes to ferroptosis induction via lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Mailloux, R.J.; Jakob, U. Fundamentals of redox regulation in biology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 701–719, Correction in Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Herve, V.; Ben Khedher, M.R.; Rabanel, J.M.; Ramassamy, C. Glutathione: An Old and Small Molecule with Great Functions and New Applications in the Brain and in Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 35, 270–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelmann, C.H.; Venkatachalam, A.; Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Germana, S.; Harry, S.A.; Rosen, P.C.; Herron, J.; Tien, P.C.; Bar-Peled, L.; et al. Lysosomal reduced thiols are essential for mouse embryonic development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2427125122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, D.A.; Laqtom, N.N.; Alchemy, G.; Dong, W.; Morrow, D.; Poltorack, C.D.; Nathanson, D.A.; Abu-Remalieh, M.; Dixon, S.J. Ferroptosis inhibition by lysosome-dependent catabolism of extracellular protein. Cell Chem. Biol. 2022, 29, 1588–1600.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rausch, M.P.; Hastings, K.T. Diverse cellular and organismal functions of the lysosomal thiol reductase GILT. Mol. Immunol. 2015, 68, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, K.T.; Cresswell, P. Disulfide reduction in the endocytic pathway: Immunological functions of gamma-interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Yang, Z.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Dongbang, S.; Kang, C.; Kim, J.S. Disulfide-cleavage-triggered chemosensors and their biological applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5071–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Moosavi Basri, S.M.; Vossoughi, M.; Pakchin, P.S.; Mirshekari, H.; Hamblin, M.R. Redox-sensitive smart nanosystems for drug and gene delivery. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016, 20, 2949–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchikama, K.; An, Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondal, M.; Swetman, W.S.; Karim, S.-U.; Shrestha, S.; Davis, A.M.; Bai, F.; Huang, F.; Clemons, T.D.; Rangachari, V. Disulfide cross-linked redox-sensitive peptide condensates are efficient cell delivery vehicles of molecular cargo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2515427122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, D.; Tao, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; He, H.; Shen, X.; Sang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Nie, Z. Efficient Cytosolic Delivery of Single-Chain Polymeric Artificial Enzymes for Intracellular Catalysis and Chemo-Dynamic Therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 998–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Terman, A.; Gustafsson, B.; Brunk, U.T. Lysosomes in iron metabolism, ageing and apoptosis. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 129, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W.; Moulis, J.-M. The bioinorganic chemistry of cadmium in the context of its toxicity. In Cadmium: From Toxicity to Essentiality; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templeton, D. Therapeutic use of chelating agents in iron overload. In Toxicology of Metals: Biochemical Aspects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995; pp. 305–331. [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow, K. Role of iron in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, D.H.; Blanchette, N.L.; Paul, B.T.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Iron and cancer: Recent insights. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2016, 1368, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Eaton, J.W.; Brunk, U.T. The role of lysosomes in iron metabolism and recycling. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011, 43, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.T.; Hamai, A.; Hienzsch, A.; Caneque, T.; Muller, S.; Wicinski, J.; Cabaud, O.; Leroy, C.; David, A.; Acevedo, V.; et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat. Chem. 2017, 9, 1025–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.e.; Wu, G.; Feng, L.; Li, J.; Xia, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhao, K. Harnessing Antioxidants in Cancer Therapy: Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Directions. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallorini, M.; Carradori, S.; Panieri, E.; Sova, M.; Saso, L. Modulation of NRF2: Biological dualism in cancer, targets and possible therapeutic applications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2024, 40, 636–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoncu, R.; Perera, R.M. Built to last: Lysosome remodeling and repair in health and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Różanowska, M.B. Lipofuscin, its origin, properties, and contribution to retinal fluorescence as a potential biomarker of oxidative damage to the retina. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Q.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, X. Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2175–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishchuk, E.V.; Concilli, M.; Iacobacci, S.; Chesi, G.; Pastore, N.; Piccolo, P.; Paladino, S.; Baldantoni, D.; Van Ijzendoorn, S.C.D.; Chan, J.; et al. Wilson disease protein ATP7B utilizes lysosomal exocytosis to maintain copper homeostasis. Dev. Cell 2014, 29, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Pu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, B.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J. The pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in Wilson’s disease: Hepatocyte injury and regulation mediated by copper metabolism dysregulation. Biometals 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, L.; Vogt, S.; Fukai, T.; Glesne, D. Copper and angiogenesis: Unravelling a relationship key to cancer progression. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009, 36, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Peng, Z.; Sang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Ding, H.; Yuan, H.; Hu, K. Copper in Cancer: From transition metal to potential target. Hum. Cell 2024, 37, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Lee, K.M.; Kim, T.; Lee, D.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, C. Trivalent Copper Ion-Mediated Dual Oxidation in the Copper-Catalyzed Fenton-Like System in the Presence of Histidine. Env. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10852–10862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, S.C.; Sasmal, D.; Datta, S.; Ram, M.; Haldar, K.K.; Mekki, A.; Sen, S. Enhancing Fenton-like Photo-degradation and Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution Reaction (OER) in Fe-doped Copper Oxide (CuO) Catalysts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05637. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Zhu, J.; Xiong, W.; Feng, J.; Yang, J.; Lu, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, P.; Feng, Y.; et al. Tumor-Generated Reactive Oxygen Species Storm for High-Performance Ferroptosis Therapy. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 11492–11506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, H.; Yang, Z.; Pang, X.; Zhao, C.; Tian, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X. Self-sufficient copper peroxide loaded pKa-tunable nanoparticles for lysosome-mediated chemodynamic therapy. Nano Today 2022, 42, 101337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yong, K. Exposure to zinc induces lysosomal-mitochondrial axis-mediated apoptosis in PK-15 cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 241, 113716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuajungco, M.P.; Kiselyov, K. The mucolipin-1 (TRPML1) ion channel, transmembrane-163 (TMEM163) protein, and lysosomal zinc handling. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2017, 22, 1330–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Su, P.; Zhao, F.; Yu, K.; Yang, X.; Lv, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J. The role of TFEB-mediated autophagy-lysosome dysfunction in manganese neurotoxicity. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2024, 7, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteiza, P.I. Zinc and the modulation of redox homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, J.Y.; Kim, H.N.; Hwang, J.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, S.E. Lysosomal dysfunction in proteinopathic neurodegenerative disorders: Possible therapeutic roles of cAMP and zinc. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Evans, E.; Platt, F.M. Lysosomal Ca2+ homeostasis: Role in pathogenesis of lysosomal storage diseases. Cell Calcium 2011, 50, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; Caler, E.V.; Andrews, N.W. Plasma membrane repair is mediated by Ca2+-regulated exocytosis of lysosomes. Cell 2001, 106, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meindl, C.; Kueznik, T.; Bosch, M.; Roblegg, E.; Frohlich, E. Intracellular calcium levels as screening tool for nanoparticle toxicity. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasivam, M.; Kaya, B.; Wijesinghe, T.; Gholam Azad, M.; Gonzalvez, M.A.; Hussaini, M.; Chekmarev, J.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Richardson, D.R. Designing tailored thiosemicarbazones with bespoke properties: The styrene moiety imparts potent activity, inhibits heme center oxidation, and results in a novel “Stealth Zinc (II) Complex”. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 1426–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmasivam, M.; Kaya, B.; Wijesinghe, T.P.; Richardson, V.; Harmer, J.R.; Gonzalvez, M.A.; Lewis, W.; Azad, M.G.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Richardson, D.R. Differential transmetallation of complexes of the anti-cancer thiosemicarbazone, Dp4e4mT: Effects on anti-proliferative efficacy, redox activity, oxy-myoglobin and oxy-hemoglobin oxidation. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 974–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, B.; Gholam Azad, M.; Suleymanoglu, M.; Harmer, J.R.; Wijesinghe, T.P.; Richardson, V.; Zhao, X.; Bernhardt, P.V.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, D.R. Isosteric Replacement of Sulfur to Selenium in a Thiosemicarbazone: Promotion of Zn(II) Complex Dissociation and Transmetalation to Augment Anticancer Efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 12155–12183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, C.; Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, S.; Shen, X.C.; Liang, H. Lysosome-Targeted Gold Nanotheranostics for In Situ SERS Monitoring pH and Multimodal Imaging-Guided Phototherapy. Langmuir 2021, 37, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.X.; Gao, Y.J.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, Z.Y.; Fan, G.; Qiao, S.L.; Zhang, R.X.; Wang, L.; Wang, H. pH-Sensitive Polymeric Nanoparticles with Gold(I) Compound Payloads Synergistically Induce Cancer Cell Death through Modulation of Autophagy. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 2869–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeage, M.J.; Maharaj, L.; Berners-Price, S.J. Mechanisms of cytotoxicity and antitumor activity of gold (I) phosphine complexes: The possible role of mitochondria. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002, 232, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, X.; Chang, X.; Liang, Z.; Lv, L.; Shan, M.; Lu, Q.; Wen, Z.; Gust, R.; Liu, W. Recent development of gold(I) and gold(III) complexes as therapeutic agents for cancer diseases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5518–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castineiras, A.; Dehnen, S.; Fuchs, A.; Garcia-Santos, I.; Sevillano, P. Stabilization of gold(I) and gold(III) complexes by pyridil bis3-hexamethylene-iminylthiosemicarbazone: Spectroscopic, structural and computational study. Dalton Trans. 2009, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Kim, D.; Seo, H.; Cho, S.W.; Ahn, K.H. Fluorescence sensing systems for gold and silver species. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 4367–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.N.; Zhang, W.X.; Gao, Y.R.; Wei, Y.N.; Shu, Y.; Wang, J.H. State-of-the-art advances of copper-based nanostructures in the enhancement of chemodynamic therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.; Miranda, M.R.; Amodio, G.; Ciaglia, T.; Bertamino, A.; Campiglia, P.; Remondelli, P.; Vestuto, V.; Moltedo, O. The Link Between Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Lysosomal Dysfunction Under Oxidative Stress in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, E.J.; Griffiths, G.M. Secretory lysosomes. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonovic, M.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins and extracellular matrix degradation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1840, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.; Lin, X.; Gao, X.; Khan, R.U.; Liao, J.Y.; Du, S.; Ge, J.; Zeng, S.; Yao, S.Q. The Dawn of a New Era: Targeting the “Undruggables” with Antibody-Based Therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7782–7853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatima, S.W.; Khare, S.K. Benefits and challenges of antibody drug conjugates as novel form of chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Taie, A.; Ozcan Bulbul, E. A paradigm use of monoclonal antibodies-conjugated nanoparticles in breast cancer treatment: Current status and potential approaches. J. Drug Target. 2024, 32, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefiasl, S.; Zare, I.; Ghovvati, M.; Ghomi, M. Enzyme-responsive materials: Properties, design, and applications. In Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Biomedical Applications; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 203–229. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, A.M.; Abdullah, N.; Rani, N.; Ahmad, N.; Amin, M. Endosomal Escape of Bioactives Deployed via Nanocarriers: Insights Into the Design of Polymeric Micelles. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 1047–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xing, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, D.; Wu, W.; Guo, J.; Mitragotri, S. Nanocarrier-mediated cytosolic delivery of biopharmaceuticals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamkundu, S.; Liu, C.F. Lysosomal-Cleavable Peptide Linkers in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzen, O.; Lecka, M.; Cwilichowska-Puslecka, N.; Majchrzak, M.; Horbach, N.; Wisniewski, J.; Jakimowicz, P.; Szpot, P.; Zawadzki, M.; Dolega-Kozierowski, B.; et al. Engineering unnatural amino acids in peptide linkers enables cathepsin-selective antibody-drug conjugates for HER2-positive breast cancer. J. Control. Release 2025, 387, 114269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheyi, R.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Linkers: An Assurance for Controlled Delivery of Antibody-Drug Conjugate. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doronina, S.O.; Bovee, T.D.; Meyer, D.W.; Miyamoto, J.B.; Anderson, M.E.; Morris-Tilden, C.A.; Senter, P.D. Novel peptide linkers for highly potent antibody-auristatin conjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 2008, 19, 1960–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemhild, K.; Besse, H.C.; Wang, B.; Pena, Q.; Sun, Q.; Omata, D.; Ozbakir, B.; Bos, C.; Scheeren, H.W.; Storm, G.; et al. Ultrasound-directed enzyme-prodrug therapy (UDEPT) using self-immolative doxorubicin derivatives. Theranostics 2022, 12, 4791–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, A.V.R.; Kumari, G.K.; Krishnamurthy, P.T.; Khaydarov, R.R. Tumor microenvironment and nanotherapeutics: Intruding the tumor fort. Biomater. Sci. 2021, 9, 7667–7704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechincha, C.; Groessl, S.; Kalis, R.; de Almeida, M.; Zanotti, A.; Wittmann, M.; Schneider, M.; de Campos, R.P.; Rieser, S.; Brandstetter, M.; et al. Lysosomal enzyme trafficking factor LYSET enables nutritional usage of extracellular proteins. Science 2022, 378, eabn5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caculitan, N.G.; Dela Cruz Chuh, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, D.; Kozak, K.R.; Liu, Y.; Pillow, T.H.; Sadowsky, J.; Cheung, T.K.; Phung, Q.; et al. Cathepsin B Is Dispensable for Cellular Processing of Cathepsin B-Cleavable Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 7027–7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisha, G.S. Biopharmaceutical applications of alpha-galactosidases. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2023, 70, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, N.; Han, H.; Guo, S.; Murthy, N. Advances in acid-degradable and enzyme-cleavable linkers for drug delivery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2025, 84, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Wang, G.; Feng, L.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ouyang, L. Targeting Lysosomal Degradation Pathways: New Strategies and Techniques for Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 3493–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndolo, R.A.; Luan, Y.; Duan, S.; Forrest, M.L.; Krise, J.P. Lysosomotropic properties of weakly basic anticancer agents promote cancer cell selectivity in vitro. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybus, W.; Trybus, E.; Krol, T. Lysosomes as a Target of Anticancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrabeta, J.; Belhajova, M.; Subrtova, H.; Merlos Rodrigo, M.A.; Heger, Z.; Eckschlager, T. Drug Sequestration in Lysosomes as One of the Mechanisms of Chemoresistance of Cancer Cells and the Possibilities of Its Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Tam, A.; Santi, S.A.; Parissenti, A.M. Role of autophagy and lysosomal drug sequestration in acquired resistance to doxorubicin in MCF-7 cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.L.; Wang, Z.V.; Ding, G.; Tan, W.; Luo, X.; Criollo, A.; Xie, M.; Jiang, N.; May, H.; Kyrychenko, V.; et al. Doxorubicin Blocks Cardiomyocyte Autophagic Flux by Inhibiting Lysosome Acidification. Circulation 2016, 133, 1668–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Kim, J.H.; Amaya, C.N.; Witcher, C.; Khammanivong, A.; Korpela, D.M.; Brown, D.R.; Taylor, J.; Bryan, B.A.; Dickerson, E.B. Propranolol Sensitizes Vascular Sarcoma Cells to Doxorubicin by Altering Lysosomal Drug Sequestration and Drug Efflux. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 614288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H.; den Dekker, A.T.; Segeletz, S.; Boersma, A.W.; de Bruijn, P.; Debiec-Rychter, M.; Taguchi, T.; Sleijfer, S.; Sparreboom, A.; Mathijssen, R.H.; et al. Lysosomal Sequestration Determines Intracellular Imatinib Levels. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, N.J.; Mancuso, R.V.; Sanvee, G.M.; Bouitbir, J.; Krahenbuhl, S. Imatinib disturbs lysosomal function and morphology and impairs the activity of mTORC1 in human hepatocyte cell lines. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 162, 112869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krchniakova, M.; Skoda, J.; Neradil, J.; Chlapek, P.; Veselska, R. Repurposing Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors to Overcome Multidrug Resistance in Cancer: A Focus on Transporters and Lysosomal Sequestration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, S.; Cormerais, Y.; Dufies, M.; Grepin, R.; Colosetti, P.; Belaid, A.; Parola, J.; Martin, A.; Lacas-Gervais, S.; Mazure, N.M.; et al. Resistance to sunitinib in renal clear cell carcinoma results from sequestration in lysosomes and inhibition of the autophagic flux. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1891–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotink, K.J.; Broxterman, H.J.; Labots, M.; de Haas, R.R.; Dekker, H.; Honeywell, R.J.; Rudek, M.A.; Beerepoot, L.V.; Musters, R.J.; Jansen, G.; et al. Lysosomal sequestration of sunitinib: A novel mechanism of drug resistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 7337–7346, Correction in Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, K.; Pahwa, S.; Wang, X.; Zhang, P.; Ding, K.; Abuznait, A.H.; Li, L.; Yue, W. Downregulation of Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide (OATP) 1B1 Transport Function by Lysosomotropic Drug Chloroquine: Implication in OATP-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, M.; Orhon, I.; Rocchi, C.; Zhou, X.; Luhr, M.; Hijlkema, K.J.; Coppes, R.P.; Engedal, N.; Mari, M.; Reggiori, F. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1435–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L.E.; Radhi, O.A.; Abdullah, M.O.; McCluskey, A.G.; Boyd, M.; Chan, E.Y.W. Lysosomotropism depends on glucose: A chloroquine resistance mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N.; Gaur, R.; Shahabuddin, S.; Chandra, P. Recent progress in lysosome-targetable fluorescent BODIPY probes for bioimaging applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 7082–7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, S.M.; Jansson, P.J.; Kalinowski, D.S.; Anjum, R.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, D.R. The growing evidence for targeting P-glycoprotein in lysosomes to overcome resistance. Future Med. Chem. 2020, 12, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhitomirsky, B.; Assaraf, Y.G. Lysosomes as mediators of drug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updat. 2016, 24, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizutani, T.; Masuda, M.; Nakai, E.; Furumiya, K.; Togawa, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Nakahira, K.; Shinkai, S.; Takahashi, K. Genuine functions of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1). Curr. Drug Metab. 2008, 9, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, T.; Wu, F.; Li, N.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, Y.M.; Zhang, J.Q.; Ma, B.L. Subcellular drug distribution: Mechanisms and roles in drug efficacy, toxicity, resistance, and targeted delivery. Drug Metab. Rev. 2018, 50, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, S.; Yang, R.; Friedlander, G.; Laouari, D. Glucose depletion enhances P-glycoprotein expression in hepatoma cells: Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 7284–7290. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Akra, L.; Bae, D.H.; Sahni, S.; Huang, M.L.H.; Park, K.C.; Lane, D.J.R.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. Tumor stressors induce two mechanisms of intracellular P-glycoprotein-mediated resistance that are overcome by lysosomal-targeted thiosemicarbazones. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 3562–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, T.; Sahni, S.; Sharp, D.M.; Arvind, A.; Jansson, P.J.; Richardson, D.R. P-glycoprotein mediates drug resistance via a novel mechanism involving lysosomal sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 31761–31771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlejnek, P. Lysosomal Drug Sequestration Mediated by ABC Transporters and Drug Resistance. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marceau, F.; Bawolak, M.T.; Lodge, R.; Bouthillier, J.; Gagne-Henley, A.; Gaudreault, R.C.; Morissette, G. Cation trapping by cellular acidic compartments: Beyond the concept of lysosomotropic drugs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 259, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcrow, P.W.; Geiger, J.D.; Chen, X. Overcoming Chemoresistance: Altering pH of Cellular Compartments by Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, P.; Strambi, A.; Zipoli, C.; Hagg-Olofsson, M.; Buoncervello, M.; Linder, S.; De Milito, A. Acidic extracellular pH neutralizes the autophagy-inhibiting activity of chloroquine: Implications for cancer therapies. Autophagy 2014, 10, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, J.V. The endosomal-lysosomal system in ADC design and cancer therapy. Expert. Opin. Biol. Ther. 2023, 23, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, P.L.; Reid, E.E.; Archer, K.E.; Harris, L.; Maloney, E.K.; Wilhelm, A.J.; Miller, M.L.; Chari, R.V.J.; Keating, T.A.; Singh, R. Optimizing Lysosomal Activation of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) by Incorporation of Novel Cleavable Dipeptide Linkers. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 4817–4825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonawane, S.J.; Kalhapure, R.S.; Govender, T. Hydrazone linkages in pH responsive drug delivery systems. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 99, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradishar, W.J. Albumin-bound paclitaxel: A next-generation taxane. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2006, 7, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadh, M.J.; Ahmed, H.H.; Kareem, R.A.; Kyada, A.; Malathi, H.; Nathiya, D.; Bhanot, D.; Taher, W.M.; Alwan, M.; Jawad, M.J.; et al. Engineered Extracellular Vesicles for Targeted Paclitaxel Delivery in Cancer Therapy: Advances, Challenges, and Prospects. Cell Mol. Bioeng. 2025, 18, 213–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonam, S.R.; Mastrippolito, D.; Georgel, P.; Muller, S. Pharmacological targets at the lysosomal autophagy-NLRP3 inflammasome crossroads. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repnik, U.; Hafner Cesen, M.; Turk, B. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death: Concepts and challenges. Mitochondrion 2014, 19 Pt A, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashima, T. Lysosomal Membrane-Permeabilization (LMP) and-Rupture (LMR) are distinct for Cell Death. Front. Cell Death 2025, 4, 1669955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iulianna, T.; Kuldeep, N.; Eric, F. The Achilles’ heel of cancer: Targeting tumors via lysosome-induced immunogenic cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbo, O.L.; Sjaastad, K.; Radomski, M.W.; Volkov, Y.; Prina-Mello, A. Magnetic Nanoparticles in Cancer Theranostics. Theranostics 2015, 5, 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, Y.S.; Pang, B.; Hyun, D.C.; Yang, M.; Xia, Y. Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. In Nanomaterials and Neoplasms; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 31–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lunov, O.; Uzhytchak, M.; Smolkova, B.; Lunova, M.; Jirsa, M.; Dempsey, N.M.; Dias, A.L.; Bonfim, M.; Hof, M.; Jurkiewicz, P.; et al. Remote Actuation of Apoptosis in Liver Cancer Cells via Magneto-Mechanical Modulation of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Cancers 2019, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostenfeld, M.S.; Hoyer-Hansen, M.; Bastholm, L.; Fehrenbacher, N.; Olsen, O.D.; Groth-Pedersen, L.; Puustinen, P.; Kirkegaard-Sorensen, T.; Nylandsted, J.; Farkas, T.; et al. Anti-cancer agent siramesine is a lysosomotropic detergent that induces cytoprotective autophagosome accumulation. Autophagy 2008, 4, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefnia, S. Mechanistic effects of arsenic trioxide on acute promyelocytic leukemia and other types of leukemias. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, R.; Nair, C.S.; Eissa, N.; Cheng, H.; Ge, P.; Ren, M.; Jaleel, A. Therapeutic Potential of Solanum Alkaloids with Special Emphasis on Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2024, 18, 3063–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Shao, R.; Wang, N.; Zhou, N.; Du, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ye, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Sulforaphane Activates a lysosome-dependent transcriptional program to mitigate oxidative stress. Autophagy 2021, 17, 872–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhowyan, A.A.; Harisa, G.I. From Molecular Therapies to Lysosomal Transplantation and Targeted Drug Strategies: Present Applications, Limitations, and Future Prospects of Lysosomal Medications. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlejnek, P.; Havlasek, J.; Pastvova, N.; Dolezel, P.; Dostalova, K. Lysosomal sequestration of weak base drugs, lysosomal biogenesis, and cell cycle alteration. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, P.M.P.; Sousa, R.W.R.; Ferreira, J.R.O.; Militao, G.C.G.; Bezerra, D.P. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in antitumor therapies based on autophagy-related mechanisms. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 168, 105582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, C.V.; Ayobami, O.J.; Ogbu, J.I.; Rosemberg, D.B.; Fajemiroye, J.O. Drugs and Interaction Attributes. In Fundamentals of Drug and Non-Drug Interactions: Physiopathological Perspectives and Clinical Approaches; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 143–176. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Sinha, K.; Sil, P.C. Cytochrome P450s: Mechanisms and biological implications in drug metabolism and its interaction with oxidative stress. Curr. Drug Metab. 2014, 15, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabanal-Ruiz, Y.; Korolchuk, V.I. mTORC1 and Nutrient Homeostasis: The Central Role of the Lysosome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, R.; Bonifacino, J.S. Lysosome Positioning Influences mTORC2 and AKT Signaling. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 26–38.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sironi, J.; Aranda, E.; Nordstrom, L.U.; Schwartz, E.L. Lysosome Membrane Permeabilization and Disruption of the Molecular Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)-Lysosome Interaction Are Associated with the Inhibition of Lung Cancer Cell Proliferation by a Chloroquinoline Analog. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 95, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Liu, X.; Tang, G. Carbon-11 and Fluorine-18 Labeled Amino Acid Tracers for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Tumors. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, A.H. Are basic and lipophilic chain groups highly required in leishmanicidal quinolines to favor the phagolysosome accumulation? Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1655979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rychahou, P.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rychagov, N.; Zaytseva, Y.Y.; Weiss, H.L.; Evers, B.M.; Guo, P. pH-responsive bond as a linker for the release of chemical drugs from RNA-drug complexes in endosome or lysosome. RNA Nanomed. 2024, 1, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Ellah, H.S.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, Y.; Baell, J.B. Unlocking pH-responsive dual payload release through hydrazone linkage chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2025, 123, 118172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alradwan, I.A.; Alnefaie, M.K.; Al Fayez, N.; Aodah, A.H.; Majrashi, M.A.; Alturki, M.; Fallatah, M.M.; Almughem, F.A.; Tawfik, E.A.; Alshehri, A.A. Strategic and Chemical Advances in Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Zheng, M.; Chen, P.; Seng Ng, C.; Peng Loh, T.; Liu, H. Linker Design for the Antibody Drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Review. ChemMedChem 2025, 20, e202500262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Rana, D.; Salave, S.; Benival, D.; Khunt, D.; Prajapati, B.G. Achieving Endo/Lysosomal Escape Using Smart Nanosystems for Efficient Cellular Delivery. Molecules 2024, 29, 3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Eslami, M.; Sahandi-Zangabad, P.; Mirab, F.; Farajisafiloo, N.; Shafaei, Z.; Ghosh, D.; Bozorgomid, M.; Dashkhaneh, F.; Hamblin, M.R. pH-Sensitive stimulus-responsive nanocarriers for targeted delivery of therapeutic agents. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 8, 696–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balce, D.R.; Allan, E.R.O.; McKenna, N.; Yates, R.M. gamma-Interferon-inducible lysosomal thiol reductase (GILT) maintains phagosomal proteolysis in alternatively activated macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 31891–31904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxon, E.; Peng, X. Recent Advances in Hydrogen Peroxide Responsive Organoborons for Biological and Biomedical Applications. Chembiochem 2022, 23, e202100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapeinos, C.; Pandit, A. Physical, chemical, and biological structures based on ROS-sensitive moieties that are able to respond to oxidative microenvironments. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5553–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Duan, S.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Y.; Yin, L. Recent Advances on Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Delivery and Diagnosis System. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 2441–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, R.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, X.; Lu, Y.; Shen, J. Functional supramolecular polymers for biomedical applications. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 498–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodic, S.; Vincent, M.D. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a key determinant of cancer’s metabolic phenotype. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Che, J.; Dai, H.; Dong, X. Recent Advances in Peptide Linkers for Antibody-Drug Conjugates. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 19871–19892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammood, M.; Craig, A.W.; Leyton, J.V. Impact of endocytosis mechanisms for the receptors targeted by the currently approved antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)—A necessity for future ADC research and development. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doronina, S.O.; Toki, B.E.; Torgov, M.Y.; Mendelsohn, B.A.; Cerveny, C.G.; Chace, D.F.; DeBlanc, R.L.; Gearing, R.P.; Bovee, T.D.; Siegall, C.B.; et al. Development of potent monoclonal antibody auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 778–784, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, S.C.; Andreyka, J.B.; Bernhardt, S.X.; Kissler, K.M.; Kline, T.; Lenox, J.S.; Moser, R.F.; Nguyen, M.T.; Okeley, N.M.; Stone, I.J.; et al. Development and properties of beta-glucuronide linkers for monoclonal antibody-drug conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2006, 17, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, W.; Yang, N.; Liu, Y. Learn from antibody-drug conjugates: Consideration in the future construction of peptide-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartak, D.G.; Gemeinhart, R.A. Matrix metalloproteases: Underutilized targets for drug delivery. J. Drug Target. 2007, 15, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rica, R.; Aili, D.; Stevens, M.M. Enzyme-responsive nanoparticles for drug release and diagnostics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubowchik, G.M.; Firestone, R.A.; Padilla, L.; Willner, D.; Hofstead, S.J.; Mosure, K.; Knipe, J.O.; Lasch, S.J.; Trail, P.A. Cathepsin B-labile dipeptide linkers for lysosomal release of doxorubicin from internalizing immunoconjugates: Model studies of enzymatic drug release and antigen-specific in vitro anticancer activity. Bioconjug Chem. 2002, 13, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, S.M.; Pedram, K.; Wisnovsky, S.; Ahn, G.; Riley, N.M.; Bertozzi, C.R. Lysosome-targeting chimaeras for degradation of extracellular proteins. Nature 2020, 584, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, G.; Riley, N.M.; Kamber, R.A.; Wisnovsky, S.; Moncayo von Hase, S.; Bassik, M.C.; Banik, S.M.; Bertozzi, C.R. Elucidating the cellular determinants of targeted membrane protein degradation by lysosome-targeting chimeras. Science 2023, 382, eadf6249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, H. Small-Molecule Ligands Targeting Lysosome-Shuttling Receptors and the Emerging Landscape of Lysosome-Targeting Chimeras. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 18040–18063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Deng, Q.; Qin, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Biomarker-activated multifunctional lysosome-targeting chimeras mediated selective degradation of extracellular amyloid fibrils. Chem 2023, 9, 2016–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Byun, I.; Kim, D.Y.; Joh, H.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, M.J. Targeted protein degradation directly engaging lysosomes or proteasomes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 3253–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormio Nunes, J.H.; Hager, S.; Mathuber, M.; Posa, V.; Roller, A.; Enyedy, E.A.; Stefanelli, A.; Berger, W.; Keppler, B.K.; Heffeter, P.; et al. Cancer Cell Resistance Against the Clinically Investigated Thiosemicarbazone COTI-2 Is Based on Formation of Intracellular Copper Complex Glutathione Adducts and ABCC1-Mediated Efflux. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13719–13732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Wu, Y.; Jin, S.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Liang, X.J. Gold nanoparticles induce autophagosome accumulation through size-dependent nanoparticle uptake and lysosome impairment. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8629–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Regar, R.; Soppina, P.; Soppina, V.; Kanvah, S. Imaging of mitochondria/lysosomes in live cells and C. elegans. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leray, X.; Conti, R.; Li, Y.; Debacker, C.; Castelli, F.; Fenaille, F.; Zdebik, A.A.; Pusch, M.; Gasnier, B. Arginine-selective modulation of the lysosomal transporter PQLC2 through a gate-tuning mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025315118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, T.; Wu, S.; Lai, Y.; Wang, H.; Hou, P.; Huang, Y.; Chen, H.H.; Su, W. CD44-hyaluronan mediating endocytosis of iron-platinum alloy nanoparticles induces ferroptotic cell death in mesenchymal-state lung cancer cells with tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance. Acta Biomater. 2024, 186, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graf, N.; Lippard, S.J. Redox activation of metal-based prodrugs as a strategy for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitambar, C.R.; Antholine, W.E. Iron-targeting antitumor activity of gallium compounds and novel insights into triapine((R))-metal complexes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 956–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lou, Q.-m.; Lai, F.-f.; Li, J.-w.; Mao, K.-j.; Wan, H.-t.; He, Y. Mechanisms of cuproptosis and its relevance to distinct diseases. Apoptosis 2024, 29, 981–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polishchuk, E.V.; Polishchuk, R.S. The emerging role of lysosomes in copper homeostasis. Metallomics 2016, 8, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, R.T.; Gukathasan, S.; Arojojoye, A.S.; Olelewe, C.; Awuah, S.G. Next Generation Gold Drugs and Probes: Chemistry and Biomedical Applications. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 6612–6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Westhuizen, D.; Bezuidenhout, D.I.; Munro, O.Q. Cancer molecular biology and strategies for the design of cytotoxic gold(I) and gold(III) complexes: A tutorial review. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 17413–17437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.C.; Lok, C.N.; Wan, P.K.; Hu, D.; Fung, Y.M.E.; Chang, X.Y.; Huang, S.; Jiang, H.; Che, C.M. An anticancer gold(III)-activated porphyrin scaffold that covalently modifies protein cysteine thiols. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunde-Dada, G.O. Ferroptosis: Role of lipid peroxidation, iron and ferritinophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2017, 1861, 1893–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Cao, F.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Cao, J.; Song, J.; Ma, Y.; Mi, W.; et al. The Ferroptosis Inhibitor Liproxstatin-1 Ameliorates LPS-Induced Cognitive Impairment in Mice. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, J.; Chen, X. In Response to Precision Medicine: Current Subcellular Targeting Strategies for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2209529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Chemical Basis | Biological/Pharmacological Implication |

|---|---|---|

| pH (~4.5–5.0) | Maintained by V-ATPase proton pump [62]. | Promotes weak-base drug trapping and hydrolysis of acid-labile bonds [63]. |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing environment with Fe2+/Cu+ cycling and low GSH | Enables Fenton chemistry; supports ROS-driven damage and ferroptosis [64]. |

| Thiol Reductase (GILT) | Cys–His–Asp catalytic triad active at pH ~5 | Catalyzes disulfide reduction; crucial for MHC class II antigen processing [65]. |

| Hydrolases | >60 enzymes (cathepsins, lipases, phosphatases, etc.) | Catalyze degradation or prodrug activation (e.g., ADCs) [66]. |

| Metal Ions (Fe, Cu, Zn) | Accumulate via autophagy and protein turnover | Drive redox reactions, ferroptosis, and chemodynamic therapy [67]. |

| Reactive Oxygen Species | H2O2 and •OH generated via Fenton/Haber–Weiss | Cause lipid peroxidation and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) [68]. |

| Strategy | Mechanism | Representative Example | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH-Triggered Release | Acid-labile linkers (hydrazone, acetal) cleave at pH ≤ 6 | Hydrazone-linked doxorubicin nanocarriers | Controlled drug release in lysosomes |

| Redox-Responsive Systems | Disulfide or ROS-sensitive bonds activated by GILT or H2O2 | Disulfide-linked prodrugs, peroxalate esters | Selective activation in oxidative lysosomes |

| Enzyme-Cleavable Linkers | Cathepsin or β-glucuronidase-mediated cleavage | ADCs with Val–Cit linker | Site-specific payload release |

| Weak-Base Trapping | Exploiting tumor lysosomal acidity and volume | Chloroquine, acridine hybrids | Preferential tumor accumulation |

| LMP-Inducing Combinations | Trigger lysosomal rupture to release trapped drugs | DpC + Doxorubicin | Overcomes Pgp-mediated resistance |

| Metal-Based Lysosomal Drugs | Redox-active metal complexes generate ROS | Cu(II)– or Au(III)–thiosemicarbazones | Induce lysosomal oxidative damage |

| Therapeutic + Diagnostic (Theranostic) Approach | Fluorescent or radiolabeled lysosomotropic drugs | Acridine–TSC hybrids, LysoRhoNox-M | Real-time tracking and dual therapy |

| Compound | Cancer Type/Population | Intervention Description | Trial Phase | Status | Clinical Identifier/ Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroquine (CQ) | Glioblastoma, pancreatic, and breast cancers | CQ as autophagy/lysosome inhibitor in combination with chemotherapy or radiotherapy | Phase II–III | Active/ completed | NCT02378532, NCT01446016 |

| Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) | Pancreatic and lung cancers | HCQ used to inhibit autophagy and enhance chemotherapy response | Phase I–II | Active/ completed | NCT01506973, NCT01273805 |

| Triapine | Cervical, ovarian, and hematologic malignancies | Ribonucleotide-reductase inhibitor with redox-active metal coordination and lysosomal accumulation | Phase II | Active/ recruiting | NCT02466971 |

| DpC | Advanced and drug-resistant solid tumors | Lysosomotropic metal-binding thiosemicarbazone inducing ROS via redox cycling | Phase I (NCT02688101) | Completed | NCT02688101 |

| COTI-2 | Head and neck, gynecologic, and brain tumors | Thiosemicarbazone analog targeting mutant p53 and lysosomal pathways | Phase I | Active | NCT02433626 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dharmasivam, M.; Kaya, B. Lysosome as a Chemical Reactor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311581

Dharmasivam M, Kaya B. Lysosome as a Chemical Reactor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311581

Chicago/Turabian StyleDharmasivam, Mahendiran, and Busra Kaya. 2025. "Lysosome as a Chemical Reactor" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311581

APA StyleDharmasivam, M., & Kaya, B. (2025). Lysosome as a Chemical Reactor. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311581