Development and Characterization of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion for Oral Mucosal Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

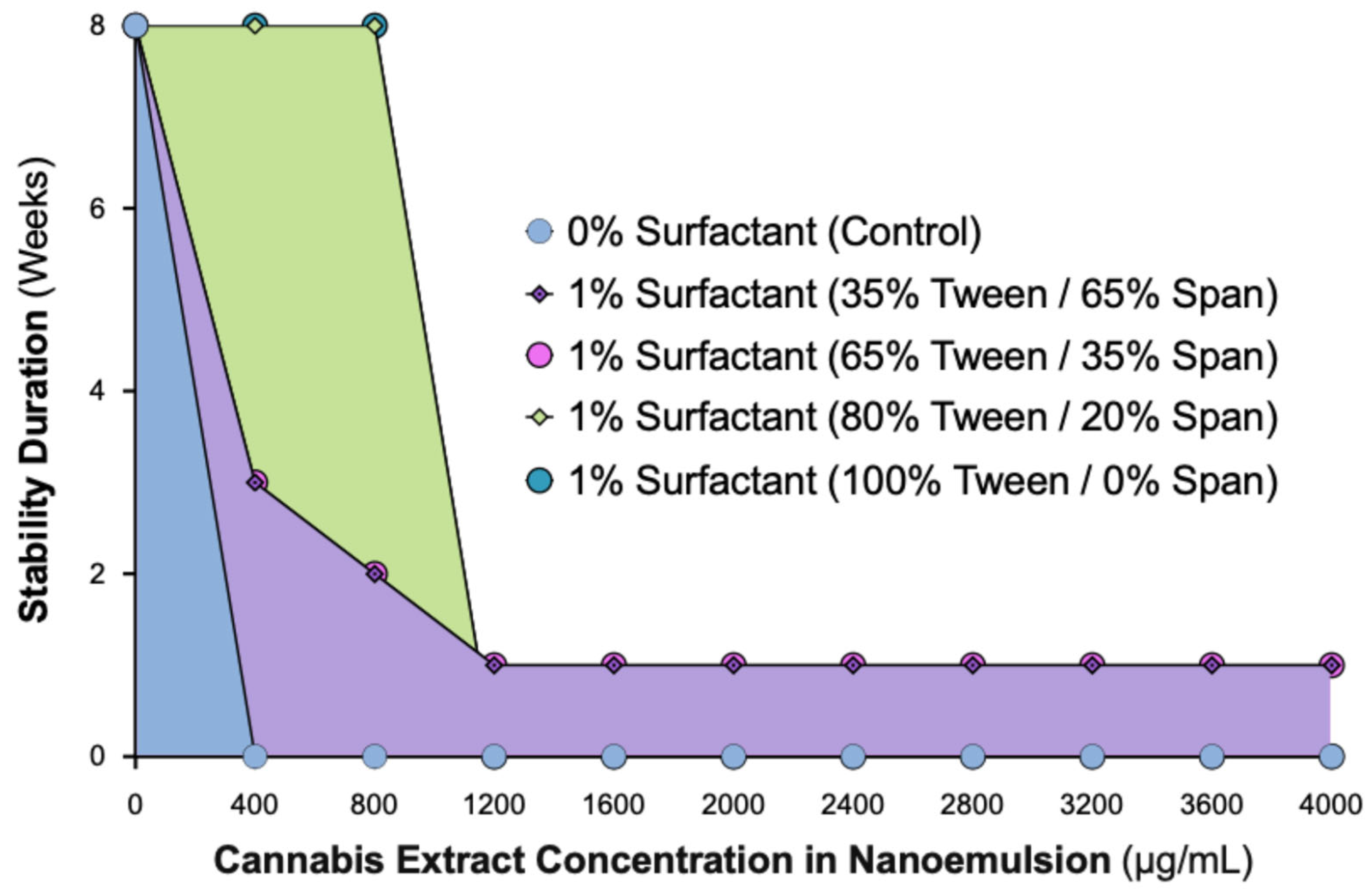

2.1. Cannabis Nanoemulsions with up to 800 µg/mL Load Are Stabilized by 1% Surfactant Containing ≥80% Tween

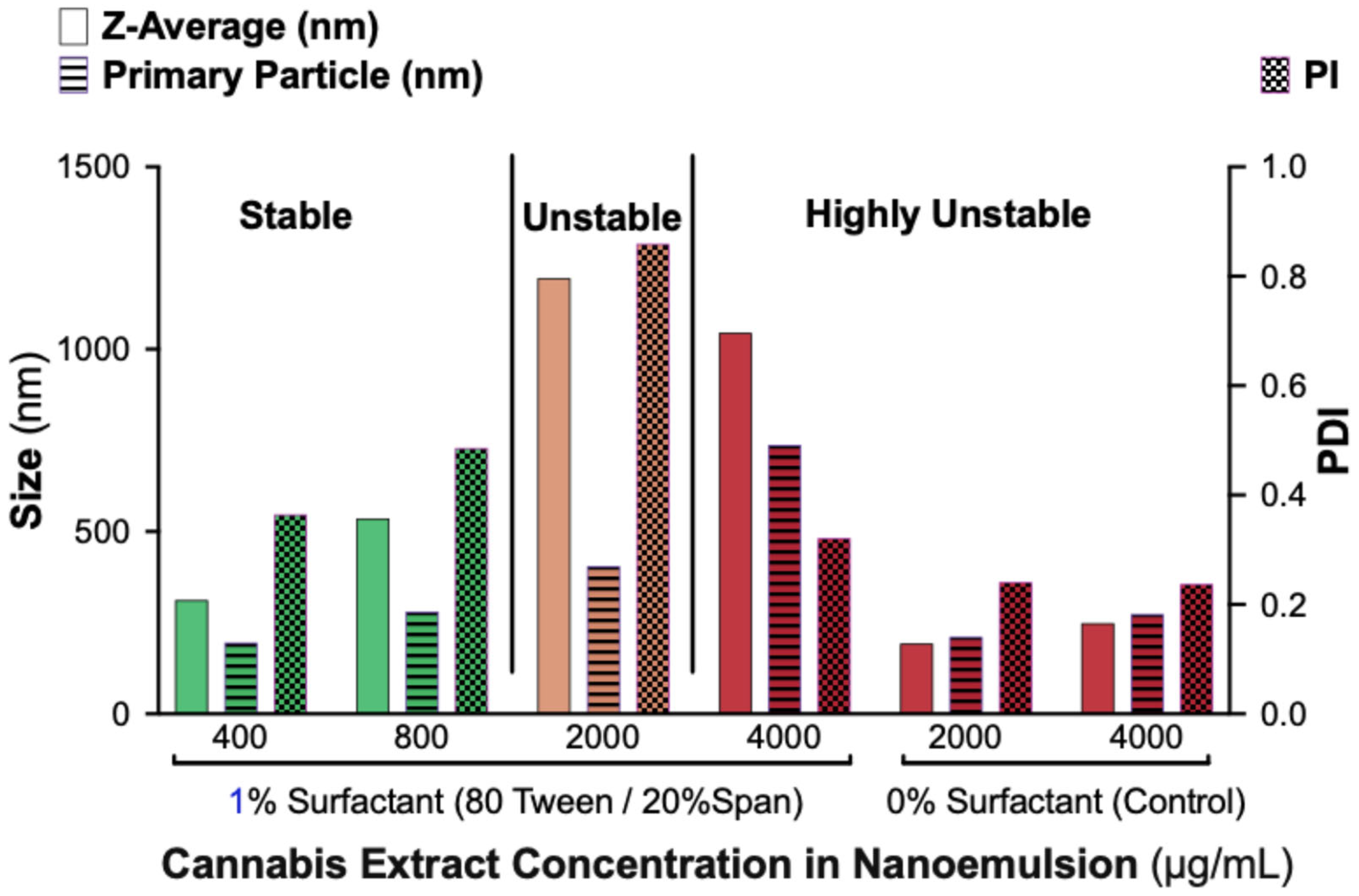

2.2. Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis Confirms Stability Limit of 800 µg/mL Cannabis in 1% Surfactant Nanoemulsions with ≥80% Tween

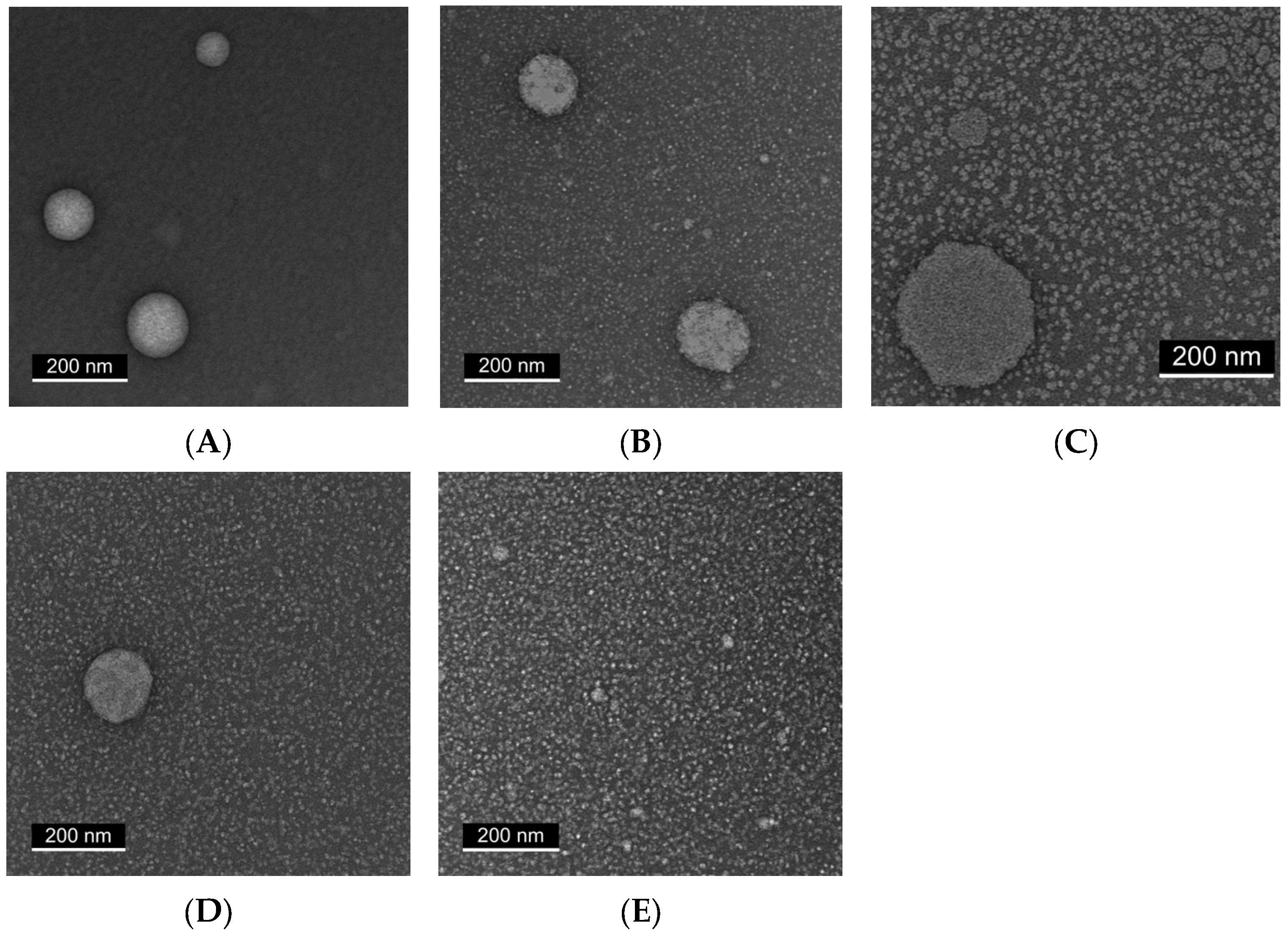

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Reveals Progressive Particle Homogeneity with Increasing Tween Content

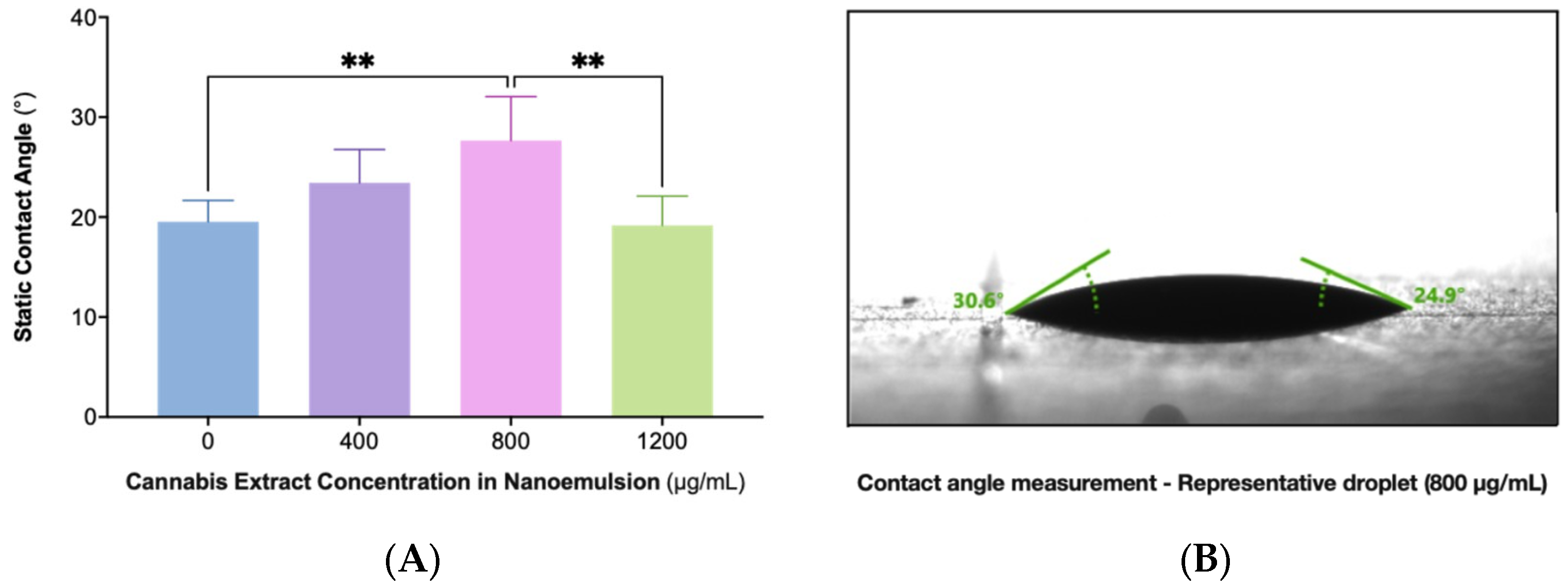

2.4. Static Contact Angle (SCA) Measurements Reveal Nonlinear Wettability with Maximal Cohesion at 800 µg/mL

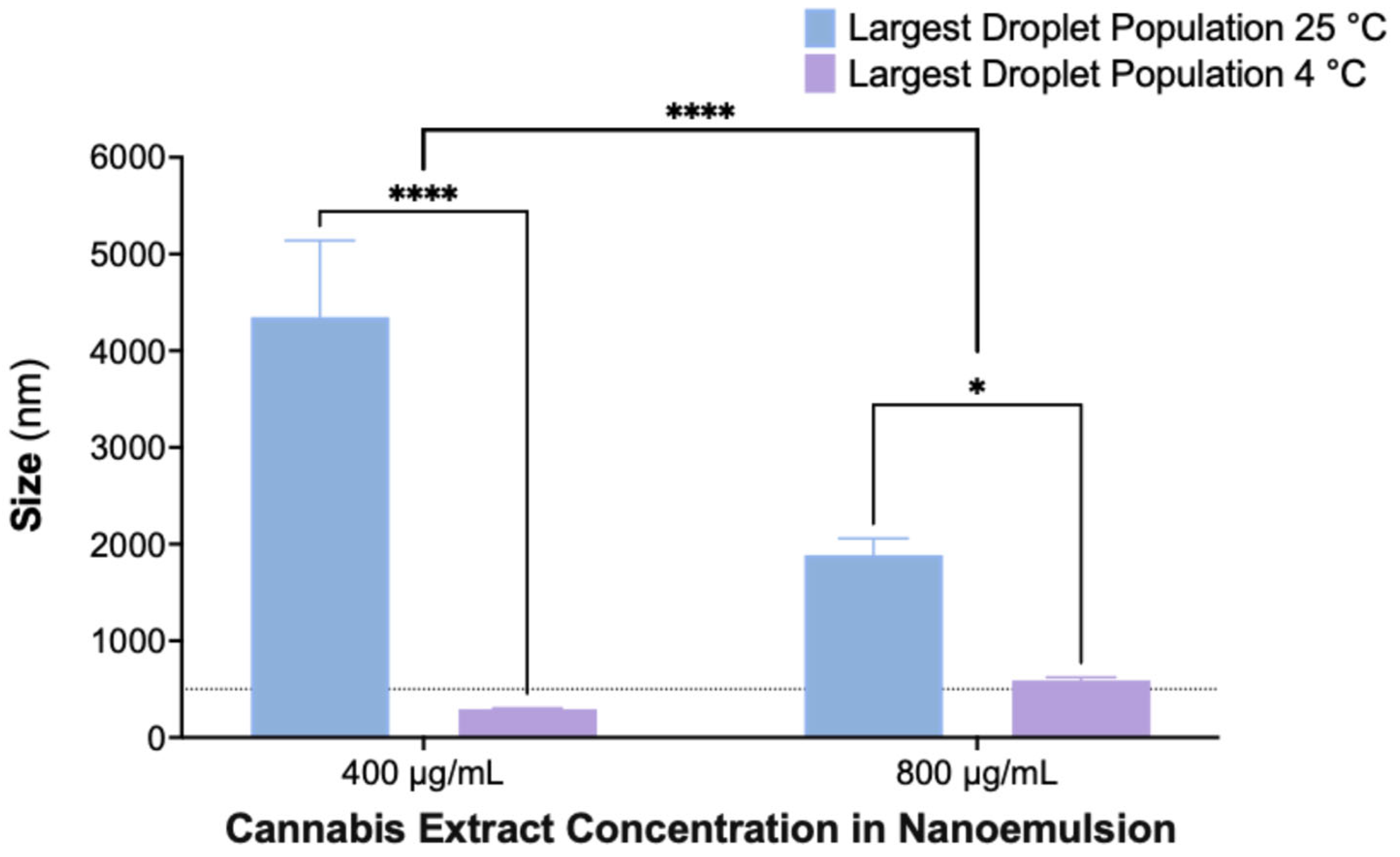

2.5. Enhanced Stability of Nanoemulsions at 4 °C Compared to Room Temperature After 30 Days

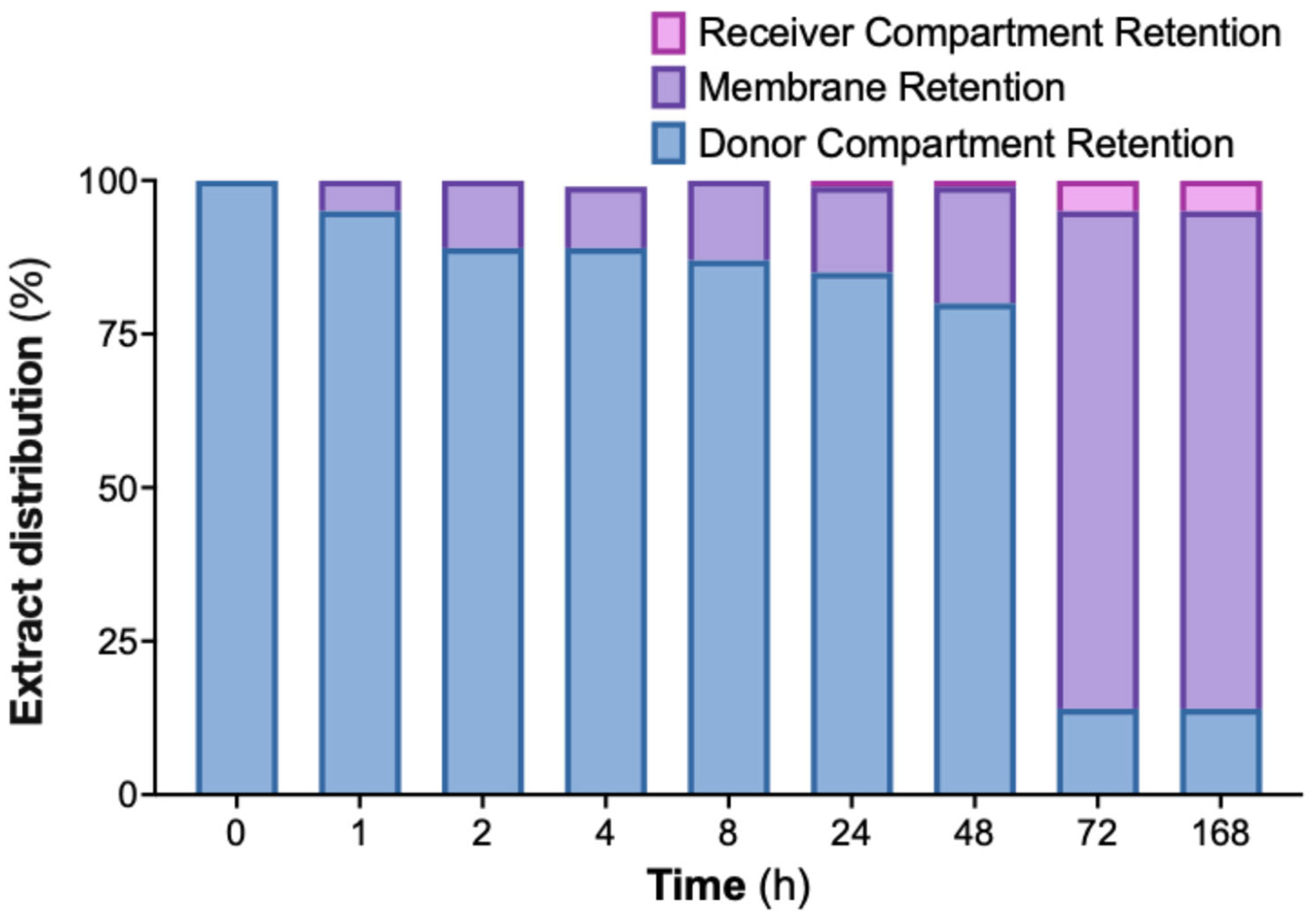

2.6. Significant In Vitro Retention of Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion on Dialysis Membrane Suggests Mucoadhesive Potential

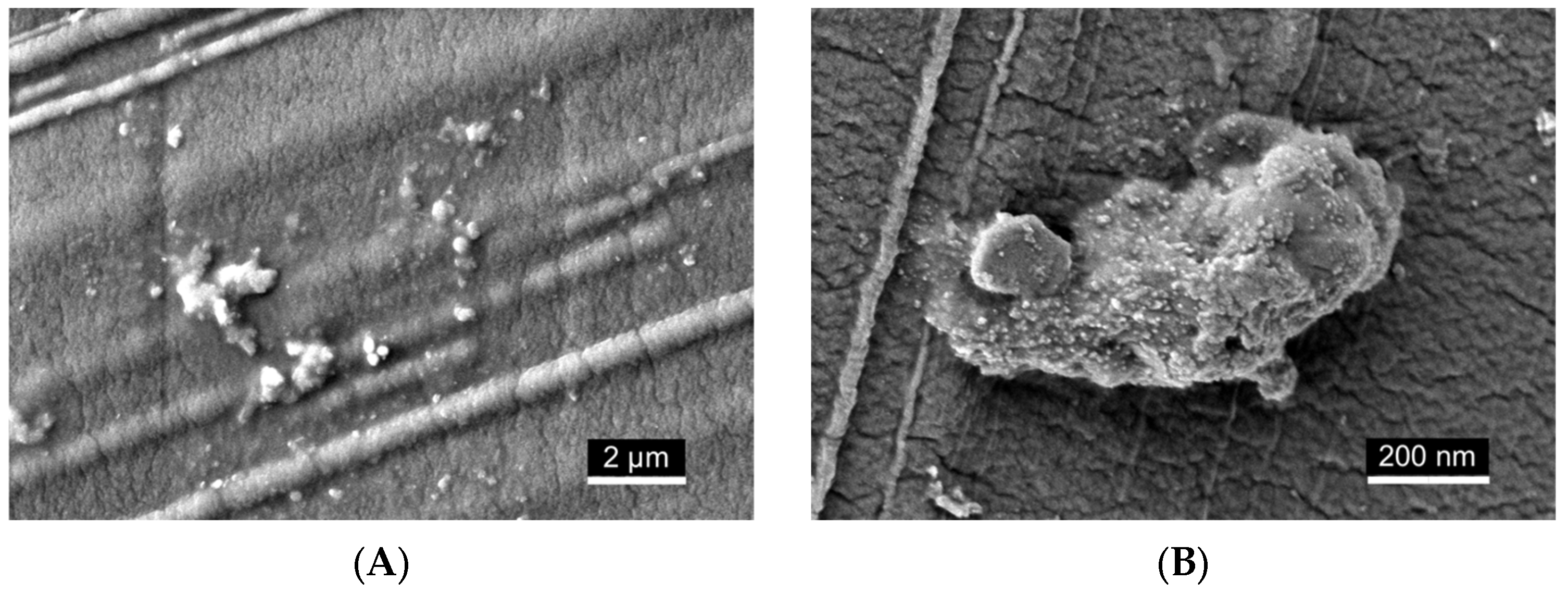

2.7. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Visualization of Nanoemulsion Aggregates on Dialysis Membrane Surface

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phytocannabinoid Extraction and Sample Preparation

4.2. Formulation Preparation

4.3. Stability Evaluation of Nanoemulsions by Visual Inspection

4.4. Dynamic Light Scattering Analysis

4.5. TEM Imaging

4.6. SCA Measurement

4.7. Phytocannabinoid Identification and Quantification

4.8. In Vitro Release Kinetics Using a Dialysis Membrane System

4.9. SEM Imaging

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2-AG | 2-arachidonoylglycerol |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AEA | N-arachidonoylethanolamine (anandamide) |

| CAN296 | CBD-rich cannabis extract (Type III strain) |

| CB1 | Cannabinoid receptor type 1 |

| CB2 | Cannabinoid receptor type 2 |

| CBC | Cannabichromene |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CD4+ | Cluster of differentiation 4 helper T cells |

| CD8+ | Cluster of differentiation 8 cytotoxic T cells |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| DSA | Drop shape analyzer |

| ECS | Endocannabinoid system |

| GVHD | Graft-versus-host disease |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HSCT | Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-2 | Interleukin-2 |

| oGVHD | Oral graft-versus-host disease |

| OLP | Oral lichen planus |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PDI | Polydispersity index |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| SCA | Static contact angle |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TAC | Tacrolimus |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| THC | Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TRP | Transient receptor potential |

| UHPLC | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

References

- Nichols, J.M.; Kaplan, B.L.F. Immune Responses Regulated by Cannabidiol. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020, 5, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, S. Cannabidiol (CBD) and its analogs: A review of their effects on inflammation. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisanti, S.; Malfitano, A.M.; Ciaglia, E.; Lamberti, A.; Ranieri, R.; Cuomo, G.; Abate, M.; Faggiana, G.; Proto, M.C.; Fiore, D.; et al. Cannabidiol: State of the art and new challenges for therapeutic applications. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 175, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blal, K.; Besser, E.; Procaccia, S.; Schwob, O.; Lerenthal, Y.; Abu Tair, J.; Meiri, D.; Benny, O. The Effect of Cannabis Plant Extracts on Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and the Quest for Cannabis-Based Personalized Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 497, Erratum in Cancers 2023, 15, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massi, P.; Solinas, M.; Cinquina, V.; Parolaro, D. Cannabidiol as potential anticancer drug. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; Pagano, S.; Pancrazi, G.L.; Valenti, C.; Bruscoli, S.; Di Michele, A.; Febo, M.; Grignani, F.; Marinucci, L. DNA damage and cell death in human oral squamous cell carcinoma cells: The potential biological effects of cannabidiol. Arch. Oral Biol. 2025, 169, 106110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 153, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, J.M.; Duncan, M.; Di Marzo, V.; Pertwee, R.G. Are cannabidiol and Δ(9)-tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blal, K.; Rosenblum, R.; Novak-Kotzer, H.; Procaccia, S.; Abu Tair, J.; Casap, N.; Meiri, D.; Benny, O. Immunomodulatory Effects of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract: A Comparative Analysis with Conventional Therapies for Oral Lichen Planus and Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozela, E.; Lev, N.; Kaushansky, N.; Eilam, R.; Rimmerman, N.; Levy, R.; Ben-Nun, A.; Juknat, A.; Vogel, Z. Cannabidiol inhibits pathogenic T cells, decreases spinal microglial activation and ameliorates multiple sclerosis-like disease in C57BL/6 mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecha, M.; Feliú, A.; Iñigo, P.M.; Mestre, L.; Carrillo-Salinas, F.J.; Guaza, C. Cannabidiol provides long-lasting protection against the deleterious effects of inflammation in a viral model of multiple sclerosis: A role for A2A receptors. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 59, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieder, S.A.; Chauhan, A.; Singh, U.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P. Cannabinoid-induced apoptosis in immune cells as a pathway to immunosuppression. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuolo, F.; Abreu, S.C.; Michels, M.; Xisto, D.G.; Blanco, N.G.; Hallak, J.E.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.; Reis, C.; Bahl, M.; et al. Cannabidiol reduces airway inflammation and fibrosis in experimental allergic asthma. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 843, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malfait, A.M.; Gallily, R.; Sumariwalla, P.F.; Malik, A.S.; Andreakos, E.; Mechoulam, R.; Feldmann, M. The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9561–9566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Almeida, V.I.; Costola-de-Souza, C.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Vitoretti, L.B.; Gimenes-Junior, J.A.; Akamine, A.T.; Crippa, J.A.; Tavares-de-Lima, W.; et al. Cannabidiol improves lung function and inflammation in mice submitted to LPS-induced acute lung injury. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 37, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donvito, G.; Nass, S.R.; Wilkerson, J.L.; Curry, Z.A.; Schurman, L.D.; Kinsey, S.G.; Lichtman, A.H. The Endogenous Cannabinoid System: A Budding Source of Targets for Treating Inflammatory and Neuropathic Pain. Neuropsychopharmacology 2018, 43, 52–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Mousawy, K.; Nagarkatti, M.; Nagarkatti, P. Endocannabinoids and immune regulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 60, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G.; Howlett, A.C.; Abood, M.E.; Alexander, S.P.; Di Marzo, V.; Elphick, M.R.; Greasley, P.J.; Hansen, H.S.; Kunos, G.; Mackie, K.; et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: Beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 588–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P.; Bátkai, S.; Kunos, G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 389–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPartland, J.M. Phylogenomic and chemotaxonomic analysis of the endocannabinoid system. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2004, 45, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis, L.; Ligresti, A.; Moriello, A.S.; Allarà, M.; Bisogno, T.; Petrosino, S.; Stott, C.G.; Di Marzo, V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 1479–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.E. An update on PPAR activation by cannabinoids. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 1899–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacology of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 74, 129–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertwee, R.G. GPR55: A new member of the cannabinoid receptor clan? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 152, 984–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, E.; Cavic, M.; Krivokuca, A.; Casadó, V.; Canela, E. The Endocannabinoid System as a Target in Cancer Diseases: Are We There Yet? Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledziński, P.; Zeyland, J.; Słomski, R.; Nowak, A. The current state and future perspectives of cannabinoids in cancer biology. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 765–775, Erratum in Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangal, N.; Erridge, S.; Habib, N.; Sadanandam, A.; Reebye, V.; Sodergren, M.H. Cannabinoids in the landscape of cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 147, 2507–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugerman, P.B.; Savage, N.W.; Walsh, L.J.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Zhou, X.J.; Khan, A.; Seymour, G.J.; Bigby, M. The pathogenesis of oral lichen planus. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2002, 13, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashimi, I.; Schifter, M.; Lockhart, P.B.; Wray, D.; Brennan, M.; Migliorati, C.A.; Axéll, T.; Bruce, A.J.; Carpenter, W.; Eisenberg, E.; et al. Oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2007, 103, S25.e1–S25.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, C.; Carrozzo, M. Oral mucosal disease: Lichen planus. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2008, 46, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, Y.; Rathi, S.K.; Joshi, A.; Das, S. Oral Lichen Planus: An Updated Review of Etiopathogenesis, Clinical Presentation, and Management. Indian. Dermatol. Online J. 2024, 15, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Ramos-García, P. Malignant transformation risk of oral lichen planus: A systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Kujan, O.; Aguirre-Urizar, J.M.; Bagan, J.V.; González-Moles, M.; Kerr, A.R.; Lodi, G.; Mello, F.W.; Monteiro, L.; Ogden, G.R.; et al. Oral potentially malignant disorders: A consensus report from an international seminar on nomenclature and classification, convened by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1862–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imanguli, M.M.; Alevizos, I.; Brown, R.; Pavletic, S.Z.; Atkinson, J.C. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuten-Shorrer, M.; Woo, S.B.; Treister, N.S. Oral graft-versus-host disease. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 58, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawardi, H.; Elad, S.; Correa, M.E.; Stevenson, K.; Woo, S.B.; Almazrooa, S.; Haddad, R.; Antin, J.H.; Soiffer, R.; Treister, N. Oral epithelial dysplasia and squamous cell carcinoma following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Clinical presentation and treatment outcomes. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2011, 46, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.E.; Travis, L.B.; Rowlings, P.A.; Socié, G.; Kingma, D.W.; Banks, P.M.; Jaffe, E.S.; Sale, G.E.; Horowitz, M.M.; Witherspoon, R.P.; et al. Risk of lymphoproliferative disorders after bone marrow transplantation: A multi-institutional study. Blood 1999, 94, 2208–2216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nosratzehi, T. Oral Lichen Planus: An Overview of Potential Risk Factors, Biomarkers and Treatments. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2018, 19, 1161–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, G.; Scully, C.; Carrozzo, M.; Griffiths, M.; Sugerman, P.B.; Thongprasom, K. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: Report of an international consensus meeting. Part 2. Clinical management and malignant transformation. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2005, 100, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlomchik, W.D. Graft-versus-host disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiser, R.; Blazar, B.R. Pathophysiology of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease and Therapeutic Targets. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2565–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payeras, M.R.; Cherubini, K.; Figueiredo, M.A.; Salum, F.G. Oral lichen planus: Focus on etiopathogenesis. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignogna, M.D.; Lo Muzio, L.; Lo Russo, L.; Fedele, S.; Ruoppo, E.; Bucci, E. Oral lichen planus: Different clinical features in HCV-positive and HCV-negative patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2000, 39, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Parkin, D.M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Bray, F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 149, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongprasom, K.; Carrozzo, M.; Furness, S.; Lodi, G. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, 7, Cd001168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Carrozzo, M.; Furness, S.; Thongprasom, K. Interventions for treating oral lichen planus: A systematic review. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 166, 938–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, M.; Conrotto, D.; Carrozzo, M.; Broccoletti, R.; Gandolfo, S.; Scully, C. Topical corticosteroids in association with miconazole and chlorhexidine in the long-term management of atrophic-erosive oral lichen planus: A placebo-controlled and comparative study between clobetasol and fluocinonide. Oral Dis. 1999, 5, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoodian, B.; Lo, J.; Lin, A. Efficacy of Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors in Oral Lichen Planus. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2015, 19, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couriel, D.; Caldera, H.; Champlin, R.; Komanduri, K. Acute graft-versus-host disease: Pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Cancer 2004, 101, 1936–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flowers, M.E.; Martin, P.J. How we treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood 2015, 125, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, B.D. Cyclosporine: A revolution in transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 1999, 31, 14s–15s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, C.M.; Goa, K.L.; Gillis, J.C. Tacrolimus. An update of its pharmacology and clinical efficacy in the management of organ transplantation. Drugs 1997, 54, 925–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, R.A.; Antin, J.H.; Karanes, C.; Fay, J.W.; Avalos, B.R.; Yeager, A.M.; Przepiorka, D.; Davies, S.; Petersen, F.B.; Bartels, P.; et al. Phase 3 study comparing methotrexate and tacrolimus with methotrexate and cyclosporine for prophylaxis of acute graft-versus-host disease after marrow transplantation from unrelated donors. Blood 2000, 96, 2062–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, P.J.; Rizzo, J.D.; Wingard, J.R.; Ballen, K.; Curtin, P.T.; Cutler, C.; Litzow, M.R.; Nieto, Y.; Savani, B.N.; Schriber, J.R.; et al. First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: Recommendations of the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012, 18, 1150–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancellor, M.B. Rationale for the Use of Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors in the Management of Oral Lichen Planus and Mucosal Inflammatory Diseases. Cureus 2024, 16, e74570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Vogelsang, G.; Flowers, M.E. Chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2003, 9, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grof, C.P.L. Cannabis, from plant to pill. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 2463–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. Non-psychotropic plant cannabinoids: New therapeutic opportunities from an ancient herb. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 515–527, Erratum in Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shabat, S.; Fride, E.; Sheskin, T.; Tamiri, T.; Rhee, M.H.; Vogel, Z.; Bisogno, T.; De Petrocellis, L.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. An entourage effect: Inactive endogenous fatty acid glycerol esters enhance 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol cannabinoid activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 353, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhao, P.Y.; Yang, X.P.; Li, H.; Hu, S.D.; Xu, Y.X.; Du, X.H. Cannabidiol regulates apoptosis and autophagy in inflammation and cancer: A review. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1094020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, K.C.R.; Miranda, G.B.A.; Dias, A.L.; Carneiro, J.R.I.; Bozza, P.T.; da Fonseca, A.C.P.; Silva, T. The endocannabinoid system in cancer biology: A mini-review of mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Oncol. Rev. 2025, 19, 1573797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blázquez, C.; González-Feria, L.; Alvarez, L.; Haro, A.; Casanova, M.L.; Guzmán, M. Cannabinoids inhibit the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in gliomas. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5617–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, S.; An, J.; Qu, G.; Song, S.; Cao, Q. Research Progress on the Mechanism of the Antitumor Effects of Cannabidiol. Molecules 2024, 29, 1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakshi, H.A.; Faruck, H.L.; Ravesh, Z.; Ansari, P.; Hannan, J.M.A.; Hashimoto, R.; Takayama, K.; Farzand, R.; Nasef, M.M.; Mensah, A.; et al. Therapeutic Potential of Cannabinoids on Tumor Microenvironment: A Molecular Switch in Neoplasia Transformation. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 15347354221096766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iozzo, M.; Sgrignani, G.; Comito, G.; Chiarugi, P.; Giannoni, E. Endocannabinoid System and Tumour Microenvironment: New Intertwined Connections for Anticancer Approaches. Cells 2021, 10, 3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.; Sadat, S.; Ebisumoto, K.; Al-Msari, R.; Miyauchi, S.; Roy, S.; Mohammadzadeh, P.; Lips, K.; Nakagawa, T.; Saddawi-Konefka, R.; et al. CBD promotes antitumor activity by modulating tumor immune microenvironment in HPV associated head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1528520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, B.; Baratta, F.; Della Pepa, C.; Arpicco, S.; Gastaldi, D.; Dosio, F. Cannabinoid Formulations and Delivery Systems: Current and Future Options to Treat Pain. Drugs 2021, 81, 1513–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Kong, Y.; Peng, J.; Sun, J.; Fan, B. Enhanced oral bioavailability of cannabidiol by flexible zein nanoparticles: In vitro and pharmacokinetic studies. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1431620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermush, V.; Mizrahi, N.; Brodezky, T.; Ezra, R. Enhancing cannabinoid bioavailability: A crossover study comparing a novel self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system and a commercial oil-based formulation. J. Cannabis Res. 2025, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brako, F.; Boateng, J. Transmucosal drug delivery: Prospects, challenges, advances, and future directions. Expert. Opin. Drug Deliv. 2025, 22, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moniruzzaman, M.; Janjua, T.I.; Martin, J.H.; Begun, J.; Popat, A. Cannabidiol-Help and hype in targeting mucosal diseases. J. Control. Release 2024, 365, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibtag, S.; Peshkovsky, A. Cannabis extract nanoemulsions produced by high-intensity ultrasound: Formulation development and scale-up. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 101953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Binder, J.; Salama, R.; Trant, J.F. Synthesis, characterization and stress-testing of a robust quillaja saponin stabilized oil-in-water phytocannabinoid nanoemulsion. J. Cannabis Res. 2021, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawin-Mikołajewicz, A.; Nawrot, U.; Malec, K.H.; Krajewska, K.; Nartowski, K.P.; Karolewicz, B.L. The Effect of High-Pressure Homogenization Conditions on the Physicochemical Properties and Stability of Designed Fluconazole-Loaded Ocular Nanoemulsions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.E.; Jensen, S.S.; Kolli, A.R.; Nikolajsen, G.N.; Bruun, H.Z.; Hoeng, J. Strategies to Improve Cannabidiol Bioavailability and Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Mei, H.C.; White, D.J.; Busscher, H.J. On the wettability of soft tissues in the human oral cavity. Arch. Oral Biol. 2004, 49, 671–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Zieliński, P.; Jelińska, A.; Gostyńska-Stawna, A. Novel Intravenous Nanoemulsions Based on Cannabidiol-Enriched Hemp Oil—Development and Validation of an HPLC-DAD Method for Cannabidiol Determination. Molecules 2025, 30, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koroleva, M.; Nagovitsina, T.; Yurtov, E. Nanoemulsions stabilized by non-ionic surfactants: Stability and degradation mechanisms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 10369–10377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, T.; Izquierdo, P.; Esquena, J.; Solans, C. Formation and stability of nano-emulsions. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2004, 108–109, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modell, J.G.; Taylor, J.P.; Lee, J.Y. Breath alcohol values following mouthwash use. JAMA 1993, 270, 2955–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, H.E.; Said, Z.; Santocildes-Romero, M.E.; Baker, S.R.; D’Apice, K.; Hansen, J.; Madsen, L.S.; Thornhill, M.H.; Hatton, P.V.; Murdoch, C. Pre-clinical evaluation of novel mucoadhesive bilayer patches for local delivery of clobetasol-17-propionate to the oral mucosa. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, M.T.; Madsen, L.S.; Saunders, D.P.; Napenas, J.J.; McCreary, C.; Ni Riordain, R.; Pedersen, A.M.L.; Fedele, S.; Cook, R.J.; Abdelsayed, R.; et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel mucoadhesive clobetasol patch for treatment of erosive oral lichen planus: A phase 2 randomized clinical trial. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2022, 51, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, A.; Pham, J.T.; Wang, D.; Brownlow, B.; Elbayoumi, T.A. Layered nanoemulsions as mucoadhesive buccal systems for controlled delivery of oral cancer therapeutics. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 1569–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, P.; Futoran, K.; Lewitus, G.M.; Mukha, D.; Benami, M.; Shlomi, T.; Meiri, D. A new ESI-LC/MS approach for comprehensive metabolic profiling of phytocannabinoids in Cannabis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blal, K.; Maroukian, G.; Shapira, A.; Procaccia, S.; Meiri, D.; Benny, O. Development and Characterization of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion for Oral Mucosal Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311525

Blal K, Maroukian G, Shapira A, Procaccia S, Meiri D, Benny O. Development and Characterization of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion for Oral Mucosal Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311525

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlal, Kifah, Georgette Maroukian, Anna Shapira, Shiri Procaccia, David Meiri, and Ofra Benny. 2025. "Development and Characterization of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion for Oral Mucosal Delivery" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311525

APA StyleBlal, K., Maroukian, G., Shapira, A., Procaccia, S., Meiri, D., & Benny, O. (2025). Development and Characterization of a High-CBD Cannabis Extract Nanoemulsion for Oral Mucosal Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311525