The Frog Skin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Suppresses Atherosclerosis by Modulating the KLF12/p300 Axis Through miR-590-5p

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Discovering Differentially Expressed miRNA Profiles by Sequencing in ox-LDL-Induced THP-1 Macrophages

2.2. miR-590-5p Suppresses the Foam Cell Formation in ox-LDL-Induced PMA-THP-1 Macrophages

2.3. miR-590-5p Alleviates Inflammatory Responses by Targeting KLF12

2.4. AMP C-1b(3-13) Alleviates Inflammatory Responses in ox-LDL-Induced Foam Cells by Upregulating the Expression of miR-590-5p

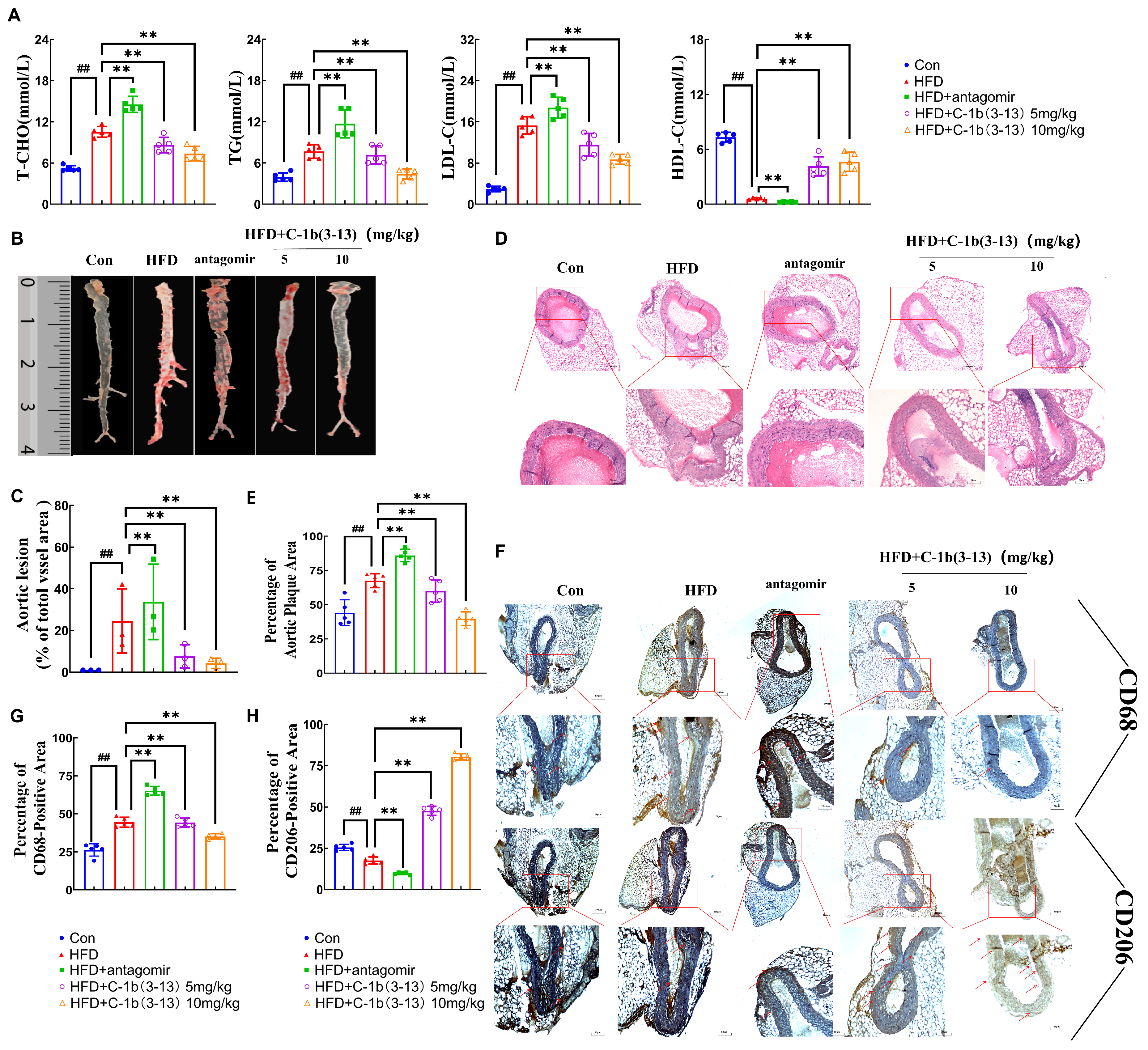

2.5. AMP C-1b(3-13) Inhibits AS in ApoE−/− Mice via the miR-590-5p/KLF12/p300 Axis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Peptide Synthesis

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. MicroRNA Sequencing (miRNA-Seq) and Data Analysis

4.4. Cell Transfection

4.5. Cholesterol Detection

4.6. Oil Red O Staining

4.7. ELISA Detection

4.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

4.9. Western Blot

4.10. miRNA Target Prediction and Bioinformatics Analyses

4.11. Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

4.12. RNA Immunoprecipitation

4.13. Animal Model

4.14. ORO Staining of the Mouse Aorta

4.15. Immunohistochemical Staining

4.16. Histopathological Analysis

4.17. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMP | antimicrobial peptide |

| CE | cholesterol ester |

| DEMs | differential expression miRNAs |

| FATP | fatty acid transport protein |

| FC | free cholesterol |

| GO | gene ontology |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin |

| HDL-C | high-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HFD | high-fat diet |

| KEGG | Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes |

| KLF12 | Krüppel-like factor 12 |

| LDL-C | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LPL | lipoprotein lipase |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| miRNAs | microRNAs |

| miRNA-Seq | MicroRNA sequencing |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| ORO staining | oil red O staining |

| ox-LDL | oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| PMA | phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| RIP | RNA immunoprecipitation |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| T-CHO | total cholesterol |

| TG | triglyceride |

References

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Corr, E.M.; Erbay, E.; Moore, K.J. Regulation of macrophage immunometabolism in atherosclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.H.; Fu, Y.C.; Zhang, D.W.; Yin, K.; Tang, C.K. Foam cells in atherosclerosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 424, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reustle, A.; Torzewski, M. Role of p38 MAPK in Atherosclerosis and Aortic Valve Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.H.; Zheng, X.L.; Tang, C.K. Nuclear Factor-κB Activation as a Pathological Mechanism of Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerosis. Adv. Clin. Chem. 2015, 70, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Tzvetkov, N.T.; Liu, X.; Yeung, A.W.K.; Xu, S.; Atanasov, A.G. Targeting Foam Cell Formation in Atherosclerosis: Therapeutic Potential of Natural Products. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019, 71, 596–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebari-Benslaiman, S.; Galicia-García, U.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Olaetxea, J.R.; Alloza, I.; Vandenbroeck, K.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, W.; Lacey, B.; Sherliker, P.; Armitage, J.; Lewington, S. Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K.; Horie, T.; Nishino, T.; Baba, O.; Kuwabara, Y.; Kimura, T. MicroRNAs and High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Metabolism. Int. Heart J. 2015, 56, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Moya, J.M.; Vilella, F.; Simón, C. MicroRNA: Key gene expression regulators. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, J.F.; Chen, W.J.; Tang, S.L.; Mo, Z.C.; Tang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Peng, J.; et al. MicroRNA-27a/b regulates cellular cholesterol efflux, influx and esterification/hydrolysis in THP-1 macrophages. Atherosclerosis 2014, 234, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotllan, N.; Zhang, X.; Canfrán-Duque, A.; Goedeke, L.; Griñán, R.; Ramírez, C.M.; Suárez, Y.; Fernández-Hernando, C. Antagonism of miR-148a attenuates atherosclerosis progression in APOBTGApobec−/−Ldlr+/− mice: A brief report. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Ni, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y. Exosomes from nicotine-stimulated macrophages accelerate atherosclerosis through miR-21-3p/PTEN-mediated VSMC migration and proliferation. Theranostics 2019, 9, 6901–6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.; Enrick, M.; Diaz, A.; Yin, L. Is miR-21 A Therapeutic Target in Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Drug Discov. Pharm. 2023, 2, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Zhao, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, M.; Han, Y. MiR-125b-5p ameliorates ox-LDL-induced vascular endothelial cell dysfunction by negatively regulating TNFSF4/TLR4/NF-κB signaling. BMC Biotechnol. 2025, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, B.; He, S.; Li, P.; Jiang, S.; Li, D.; Lin, J.; Feinberg, M.W. MicroRNA-181 in cardiovascular disease: Emerging biomarkers and therapeutic targets. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem Büyükkiraz, M.; Kesmen, Z. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): A promising class of antimicrobial compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1573–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucataru, C.; Ciobanasu, C. Antimicrobial peptides: Opportunities and challenges in overcoming resistance. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 286, 127822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Song, Y. Mechanism of Antimicrobial Peptides: Antimicrobial, Anti-Inflammatory and Antibiofilm Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, D.G. Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs) with Dual Mechanisms: Membrane Disruption and Apoptosis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Dong, Z.; Mao, X.; Sun, Y.; Li, F.; Shang, D. Structure-activity analysis and biological studies of chensinin-1b analogues. Acta Biomater. 2016, 37, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Duan, X.; Ma, X.; Liu, C.; Shang, D. Chensinin-1b Alleviates DSS-Induced Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Inducing Macrophage Switching from the M1 to the M2 Phenotype. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Qu, W.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Y.; Shang, D. The antimicrobial peptide chensinin-1b alleviates the inflammatory response by targeting the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway and inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and LPS-mediated sepsis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 165, 115227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.F.; Hao, Z.M.; Cui, X.Y.; Liu, W.Q.; Li, M.M.; Shang, D.J. Frog Skin Antimicrobial Peptide 3-13 and Its Analogs Alleviate Atherosclerosis Cholesterol Accumulation in Foam Cells via PPARγ Signaling Pathway. Cells 2025, 14, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anilkumar, S.; Wright-Jin, E. NF-κB as an Inducible Regulator of Inflammation in the Central Nervous System. Cells 2024, 13, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiernan, R.; Brès, V.; Ng, R.W.; Coudart, M.P.; El Messaoudi, S.; Sardet, C.; Jin, D.Y.; Emiliani, S.; Benkirane, M. Post-activation turn-off of NF-kappa B-dependent transcription is regulated by acetylation of p65. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2758–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pietrantonio, N.; Di Tomo, P.; Mandatori, D.; Formoso, G.; Pandolfi, A. Diabetes and Its Cardiovascular Complications: Potential Role of the Acetyltransferase p300. Cells 2023, 12, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Lin, L.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; Ren, J. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology and mechanisms. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzon, J.F.; Otsuka, F.; Virmani, R.; Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1852–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, D.; Rayner, K.J. Macrophage miRNAs in atherosclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1861 Pt B, 2087–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávalos, A.; Goedeke, L.; Smibert, P.; Ramírez, C.M.; Warrier, N.P.; Andreo, U.; Cirera-Salinas, D.; Rayner, K.; Suresh, U.; Pastor-Pareja, J.C.; et al. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9232–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, L.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H. miR-122/PPARβ axis is involved in hypoxic exercise and modulates fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle of obese rats. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazari-Jahantigh, M.; Wei, Y.; Noels, H.; Akhtar, S.; Zhou, Z.; Koenen, R.R.; Heyll, K.; Gremse, F.; Kiessling, F.; Grommes, J.; et al. MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in macrophages. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 4190–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, J.; Deng, Q.; Deng, X.; Zhong, W.; Liu, S.; Zhong, Z. MicroRNA-146a-5p alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced NLRP3 inflammasome injury and pro-inflammatory cytokine production via the regulation of TRAF6 and IRAK1 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwal, T.S.; Singh, N.; Sharma, U.; Bazala, S.; Rani, M.; Behera, A.; Kumawat, R.K.; Kumar, P.; Uttam, V.; Khandelwal, A.; et al. miR-590-5p: A double-edged sword in the oncogenesis process. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2022, 32, 100593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Luo, Y.; Cong, Z.; Mu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhong, M. MicroRNA-590-5p Inhibits Intestinal Inflammation by Targeting YAP. J. Crohns Colitis 2018, 12, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Su, H.; He, J.B.; Li, H.Q.; Sha, J.J. MiR-590-5p alleviates intracerebral hemorrhage-induced brain injury through targeting Peli1 gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 504, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, A.; Zou, Y.; Ge, J. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ Antagonizes LOX-1-Mediated Endothelial Injury by Transcriptional Activation of miR-590-5p. PPAR Res. 2019, 2019, 2715176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Mao, X.; Guan, Y.; Kang, Y.; Shang, D. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activities of three chensinin-1 peptides containing mutation of glycine and histidine residues. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Fu, L.; Wen, W.; Dong, N. The dual antimicrobial and immunomodulatory roles of host defense peptides and their applications in animal production. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantic, J.M.; Jovanovic, I.P.; Radosavljevic, G.D.; Arsenijevic, N.N.; Conlon, J.M.; Lukic, M.L. The Potential of Frog Skin-Derived Peptides for Development into Therapeutically-Valuable Immunomodulatory Agents. Molecules 2017, 22, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, V.; Bojarska, J.; Chai, T.T.; Elnagdy, S.; Kaczmarek, K.; Matsoukas, J.; New, R.; Parang, K.; Lopez, O.P.; Parhiz, H.; et al. A Global Review on Short Peptides: Frontiers and Perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvinen, T.A.; May, U.; Prince, S. Systemically Administered, Target Organ-Specific Therapies for Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23556–23571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa, J.M. Immunogenicity in biologic therapy: Implications for dermatology. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013, 104, 471–479, (In English and Spanish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Meng, X.; Zhang, D.; Kou, Z. Antibacterial activity of chensinin-1b, a peptide with a random coil conformation, against multiple-drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 143, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, F.; Li, M.-M.; Qiu, Z.-P.; Li, Z.-J.; Shang, D.-J. The Frog Skin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Suppresses Atherosclerosis by Modulating the KLF12/p300 Axis Through miR-590-5p. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311497

Fan F, Li M-M, Qiu Z-P, Li Z-J, Shang D-J. The Frog Skin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Suppresses Atherosclerosis by Modulating the KLF12/p300 Axis Through miR-590-5p. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311497

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Fan, Meng-Miao Li, Zhong-Peng Qiu, Zhen-Jia Li, and De-Jing Shang. 2025. "The Frog Skin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Suppresses Atherosclerosis by Modulating the KLF12/p300 Axis Through miR-590-5p" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311497

APA StyleFan, F., Li, M.-M., Qiu, Z.-P., Li, Z.-J., & Shang, D.-J. (2025). The Frog Skin-Derived Antimicrobial Peptide Suppresses Atherosclerosis by Modulating the KLF12/p300 Axis Through miR-590-5p. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11497. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311497