Mathematical Modeling of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus acidophilus Growth Based on Experimental Mixed Batch Cultivation

Abstract

1. Introduction

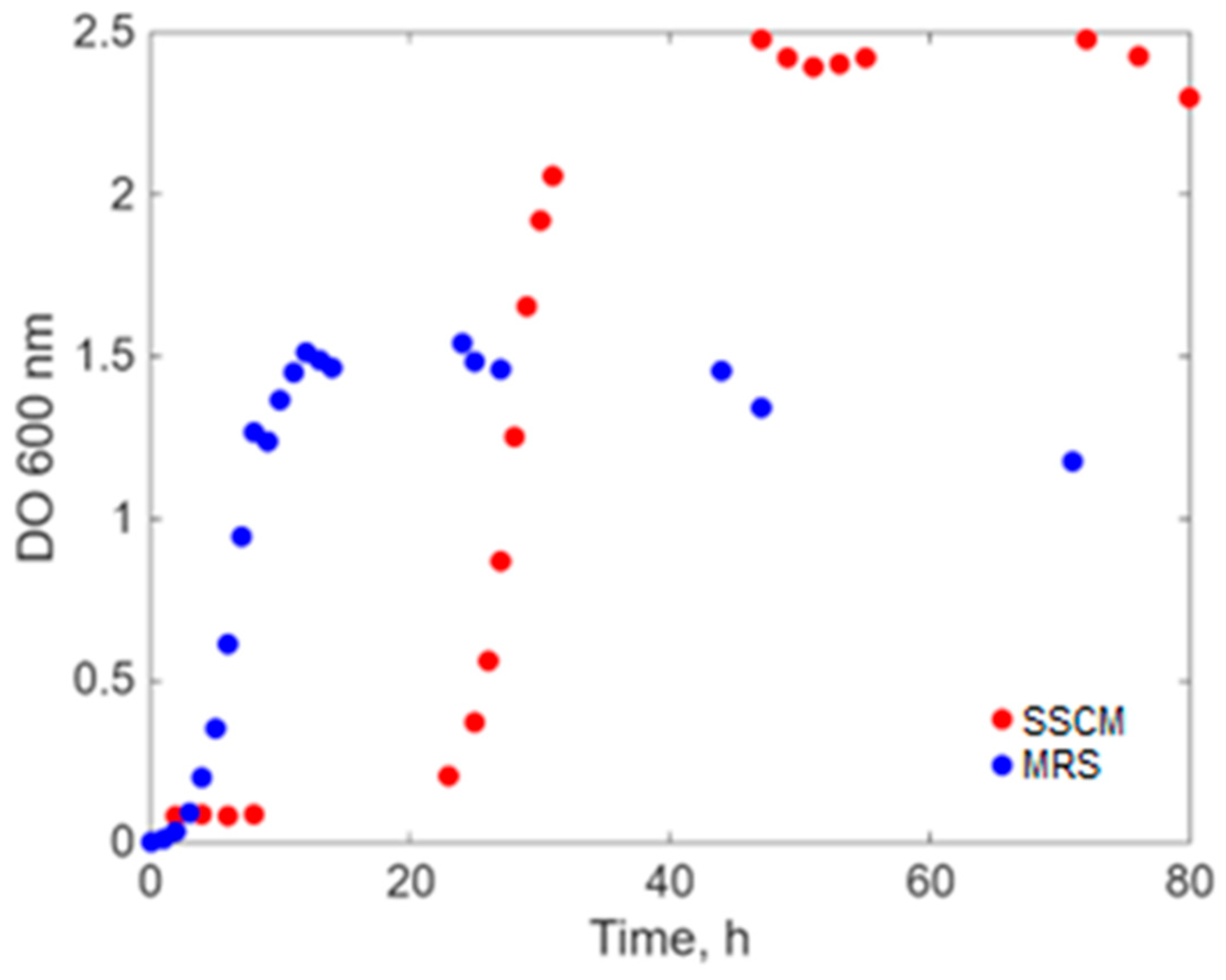

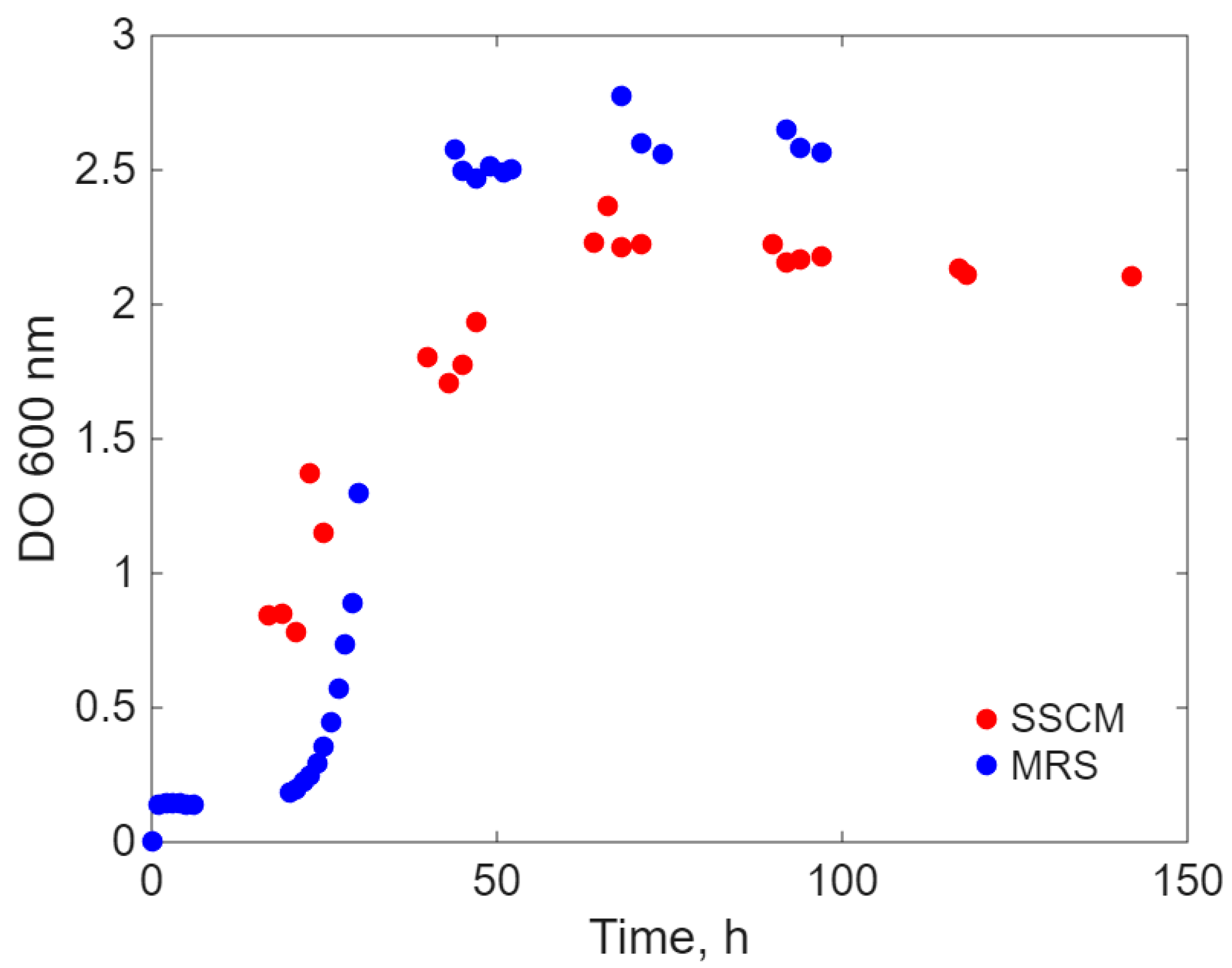

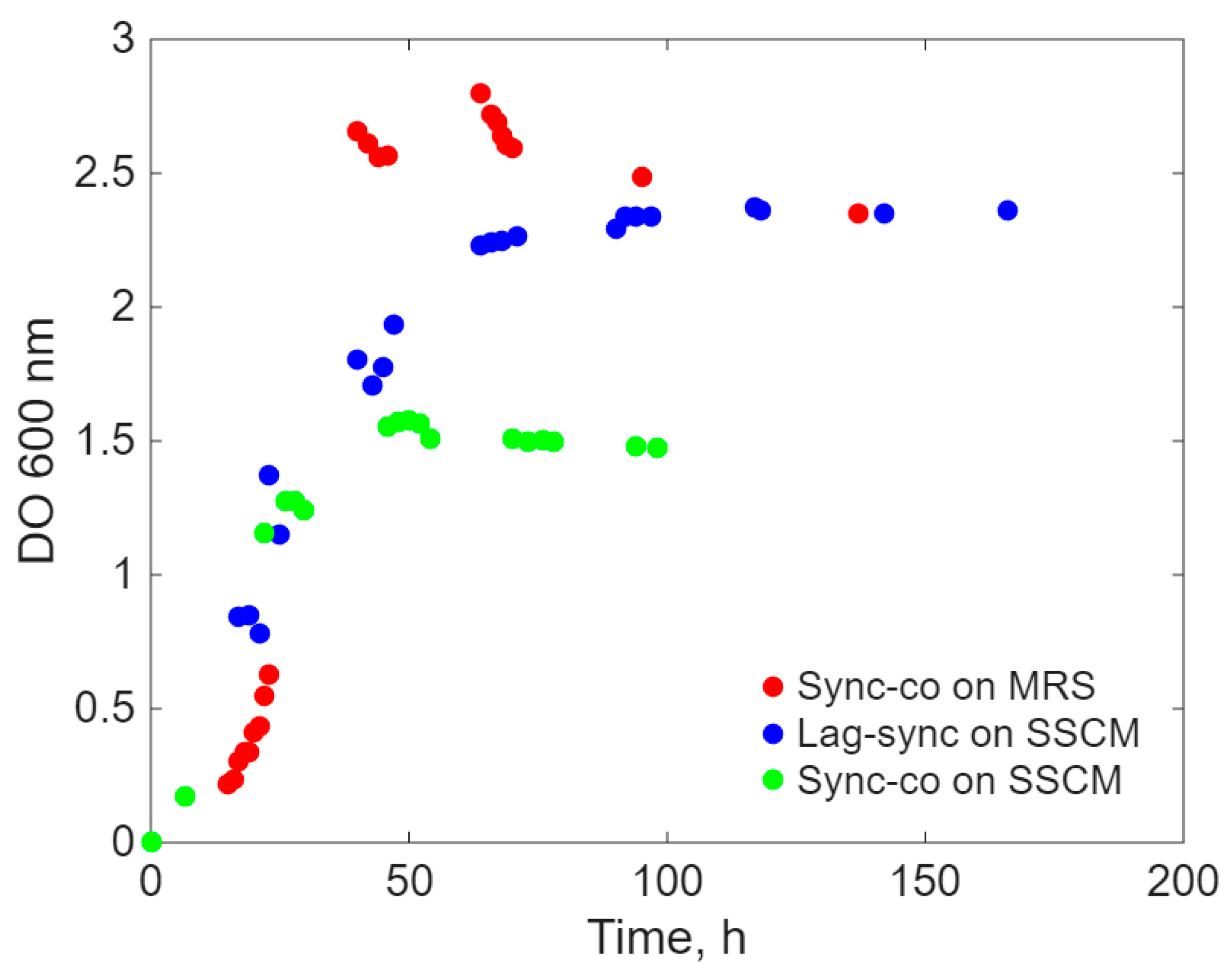

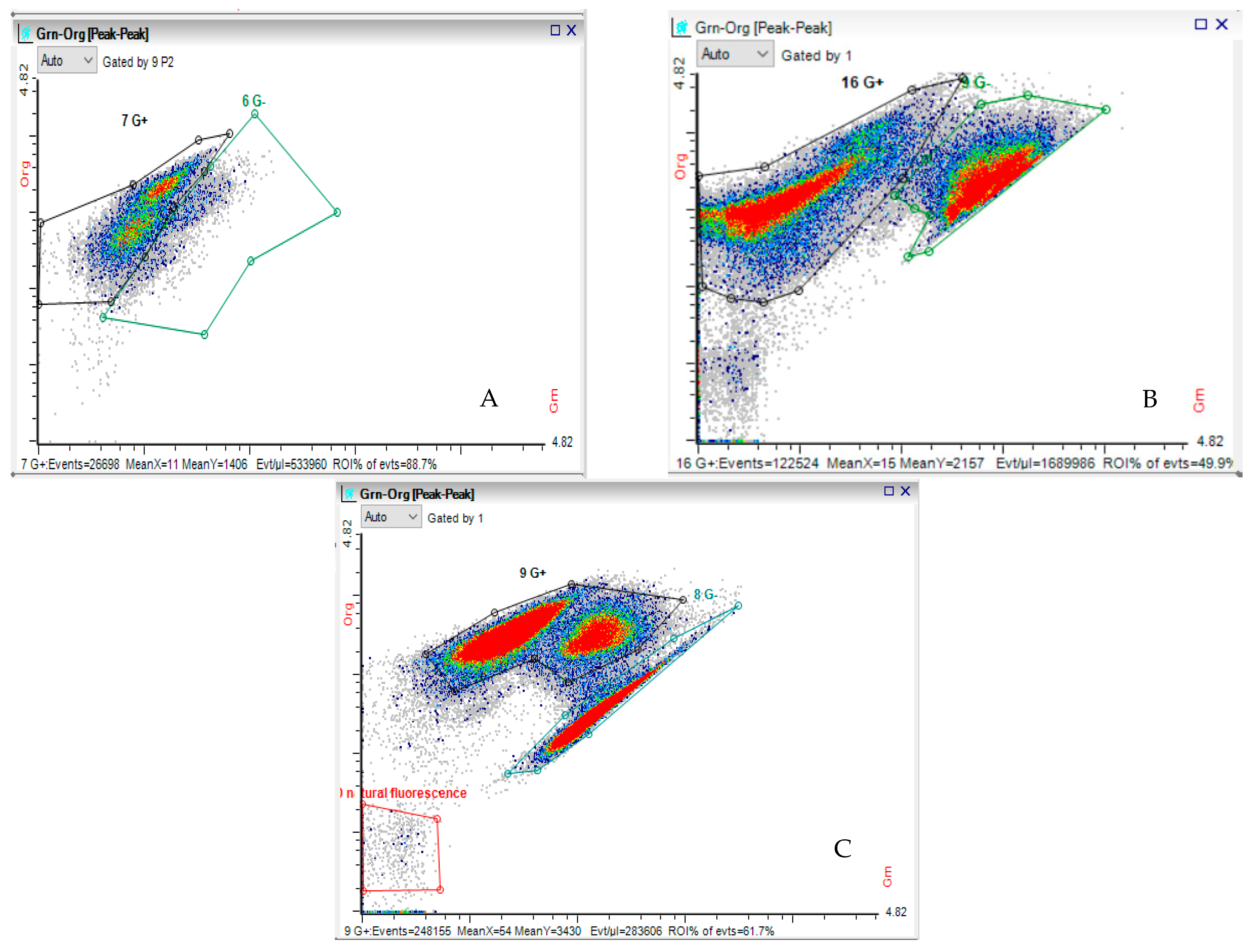

2. Results

- a.

- Simultaneous inoculation and cultivation on the two different culture media (Sync-co), with the same inoculum concentration.

- b.

- Inoculation with E. coli after the lag period (approximately 20 h) of L. acidophilus only on the SSCM culture medium (Lag-Sync) to test the probiotic’s capacity to cope with the proliferation of the pathogenic microorganism on a culture medium favorable to E. coli.

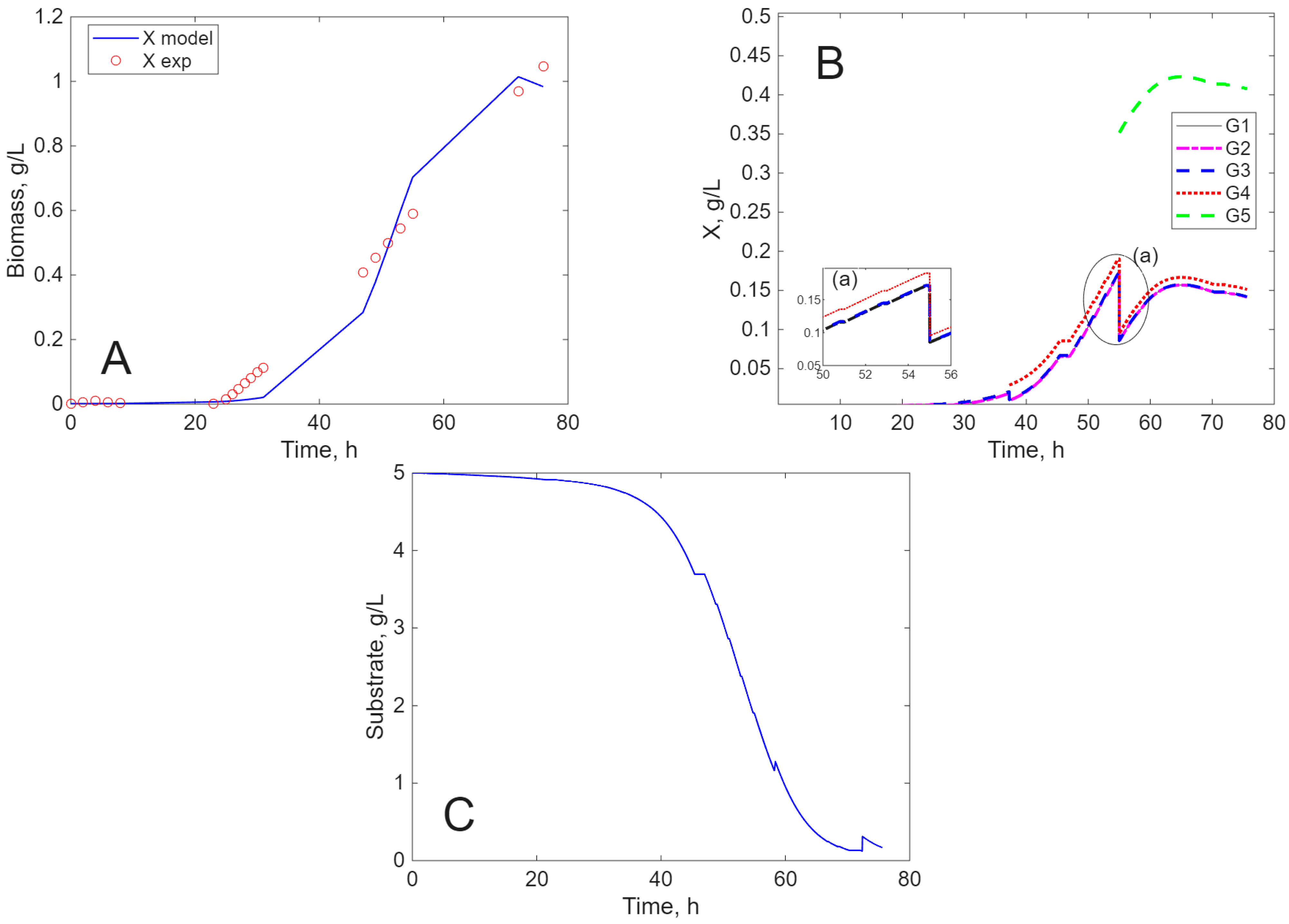

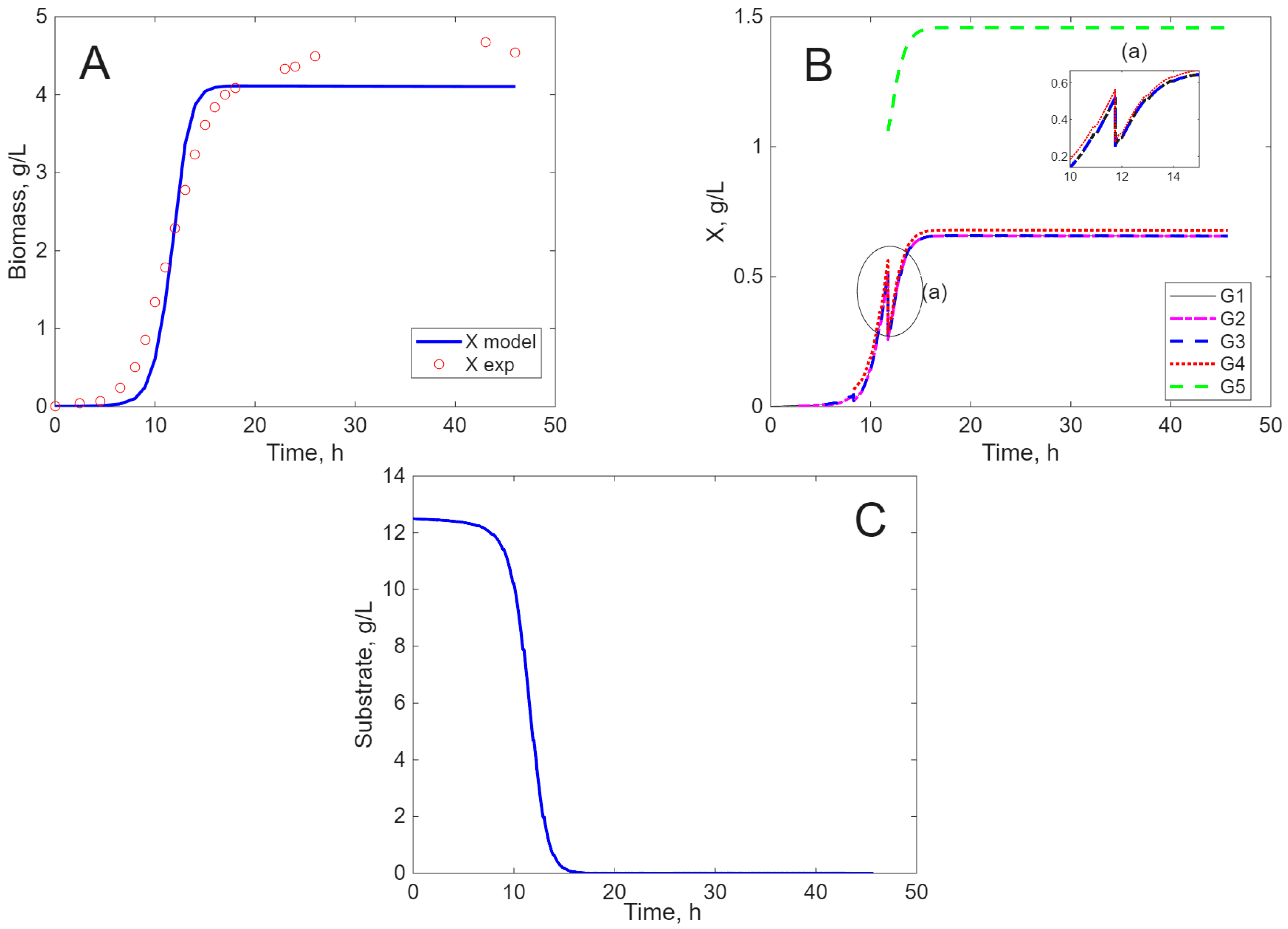

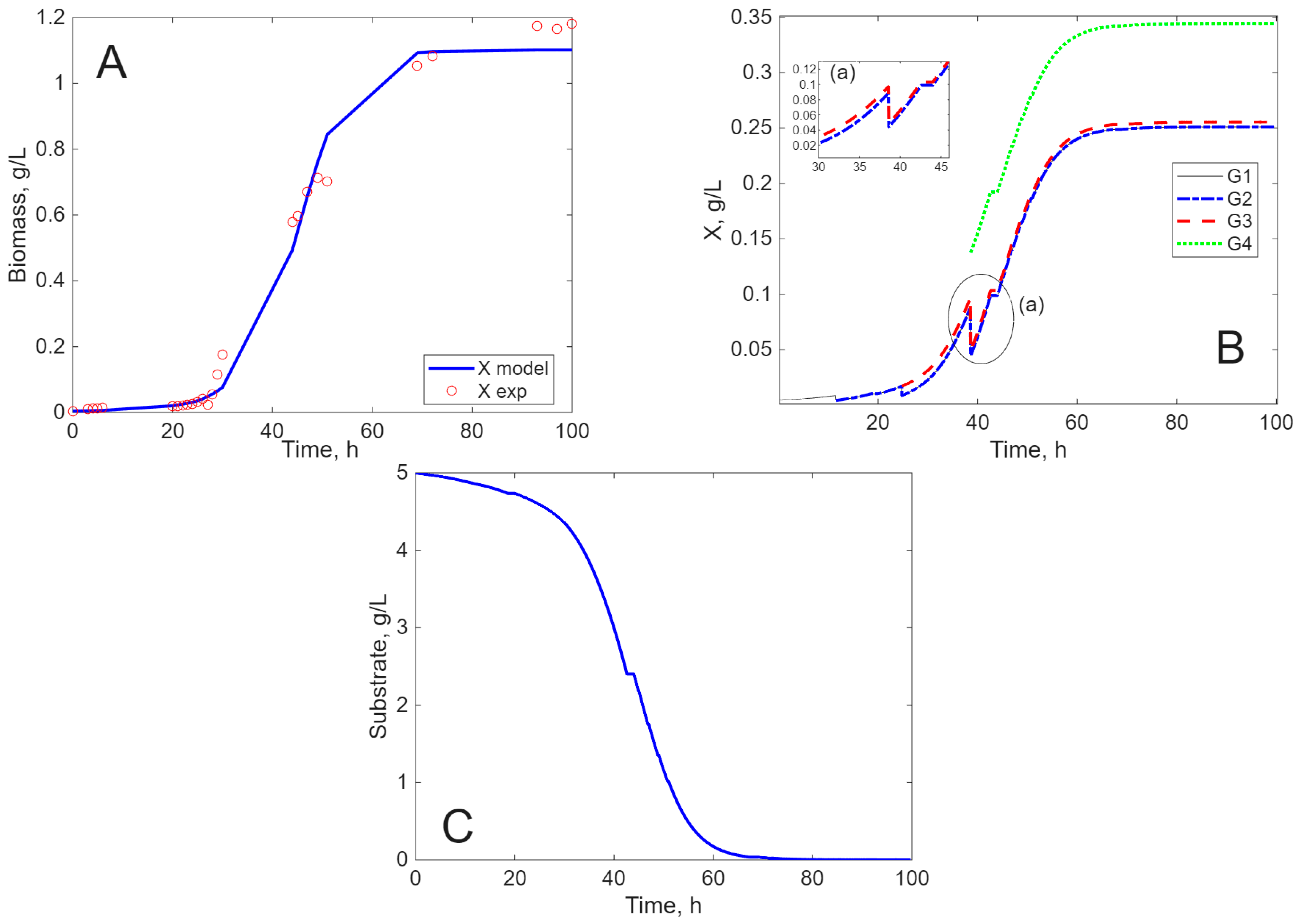

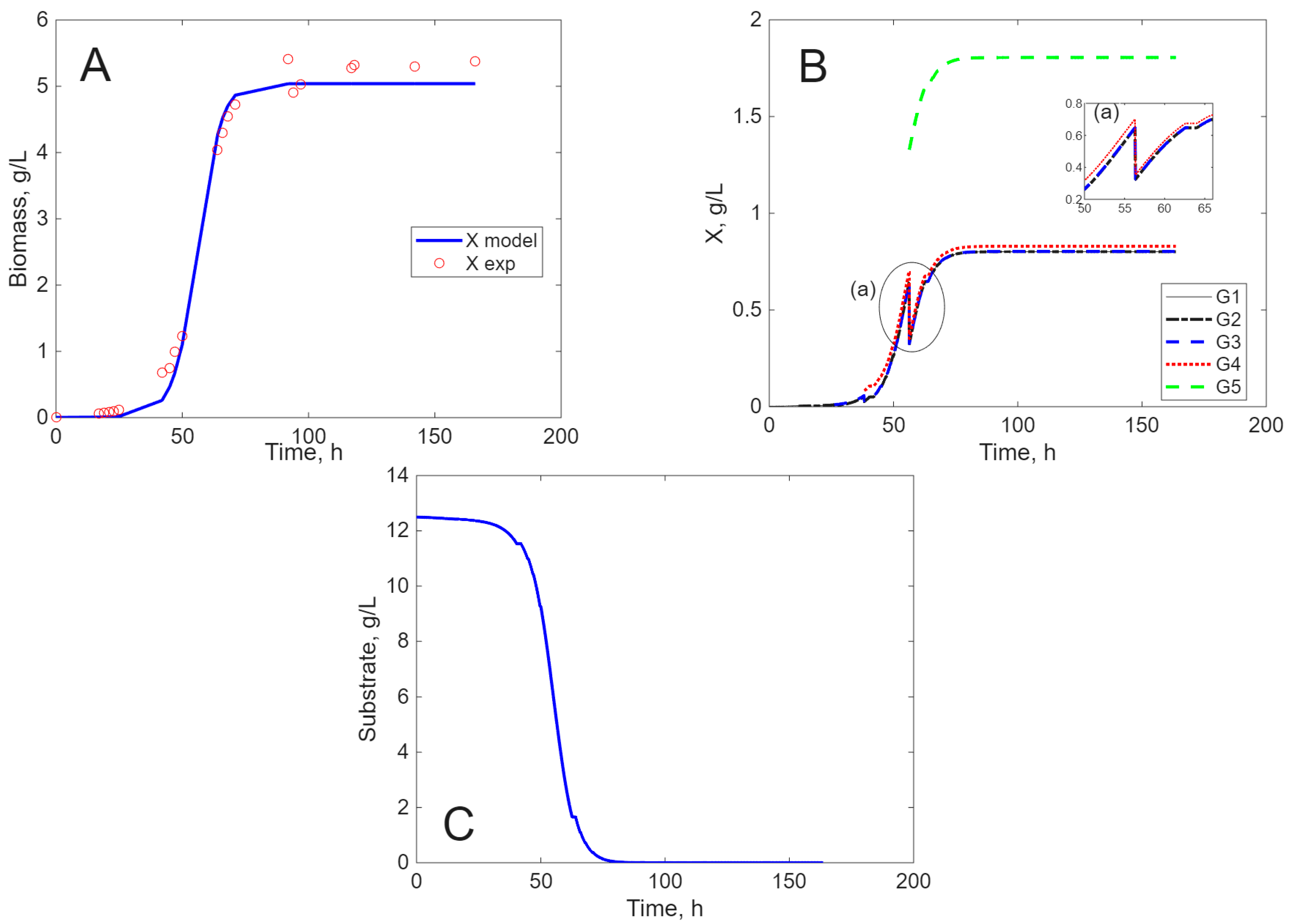

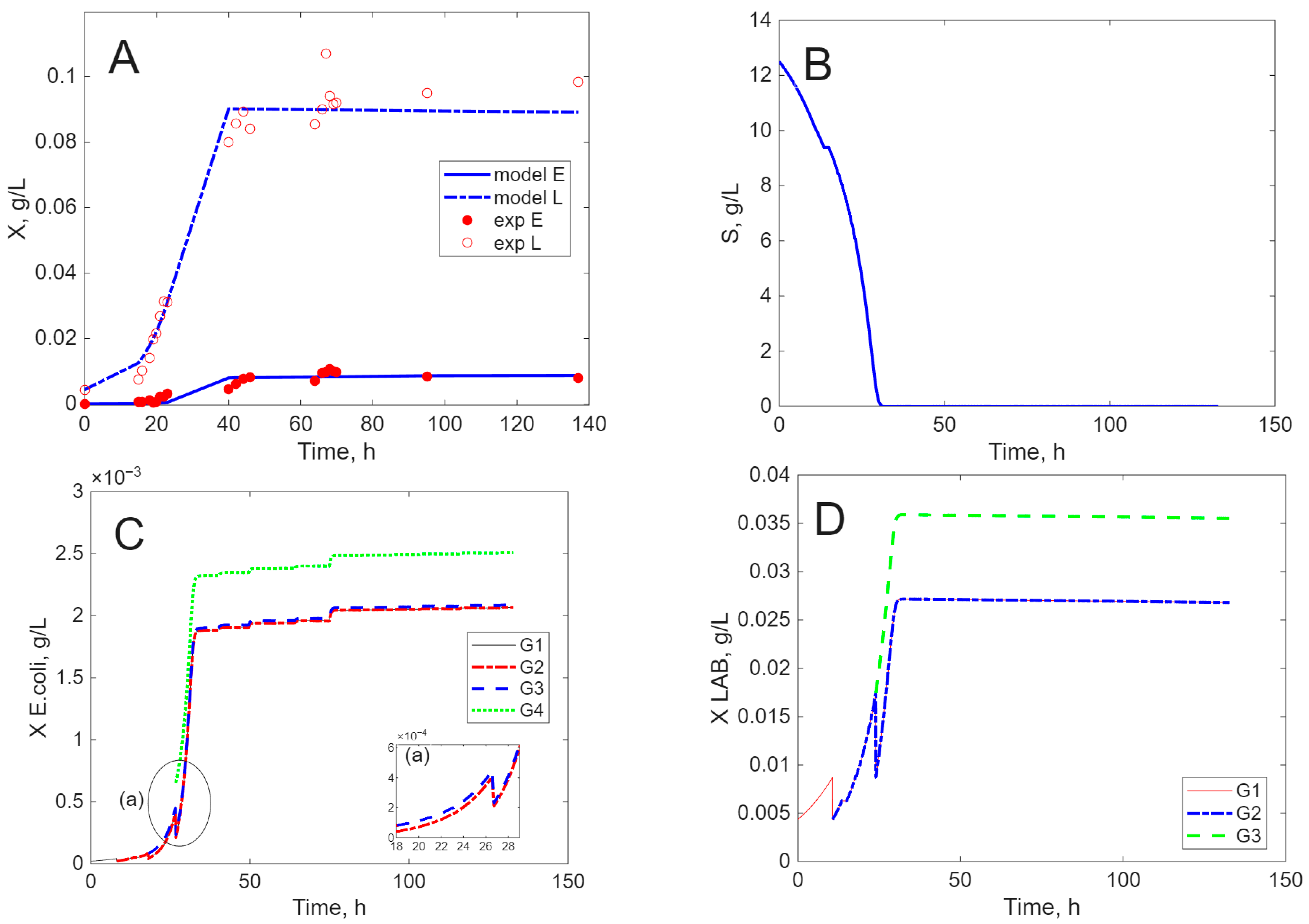

Modeling Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Equipment and Process Parameters

4.3. Methods of Analysis

4.4. Mathematical Modeling

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| K | (g·L−1) affinity constant |

| k | (h−1) velocity constant |

| S | (g·L−1) substrate concentration |

| t | (h) time |

| X | (g·L−1) cell concentration |

| P | (g·L−1) lactic acid concentration |

| YXS | (gcel·g−1substrate) transformation yield |

| Greek Letters | |

| μ | (s−1) specific growth velocity |

| v | (s−1) velocity of dead cell transformation |

| θ | (s) time delay for the dead cell transformation |

| Subscripts | |

| d | dead |

| k, l | current generation |

| n | E. coli population |

| m | L. acidophilus population |

References

- Chen, G.Q. New challenges and opportunities for industrial biotechnology. Microb. Cell Fact. 2012, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitney, R.; Freemont, P. Synthetic biology—The state of play. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, K.; Pozo, M.; Tsao, C.Y.; Hauk, P.; Bentley, W.E. Bacterial co-culture with cell signaling translator and growth controller modules for autonomously regulated culture composition. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidberg, K.; Pilheden, S.; Relloso Ortiz de Uriarte, M.; Jonsson, A.-B. Internalization of Lactobacillus crispatus Through Caveolin-1-Mediated Endocytosis Boosts Cellular Uptake but Blocks the Transcellular Passage of Neisseria meningitidis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amirlo, M.G.; Bayat, M.; Iranbakhsh, A.; Khalilian, M. Effects of Bacteriocin Extracted from Lactobacillus plantarum on Treatment-Resistant Escherichia coli Bacteria Isolated from Humans and Livestock. J. Microbiota 2024, 1, e153862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.R.S.; de Souza de Azevedo, P.O.; Converti, A.; de Souza Oliveira, R.P. Cultivation of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Potential of Partially Purified Bacteriocin-like Inhibitory Substances against Cariogenic and Food Pathogens. Fermentation 2022, 8, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selegato, D.M.; Castro-Gamboa, I. Enhancing chemical and biological diversity by co-cultivation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, G.; Asgari, B.; Smit, B.; Hatje, E.; Kuballa, A.; Katouli, M. The Efficacy of Selected Probiotic Strains and Their Combination to Inhibit the Interaction of Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) with a Co-Culture of Caco-2:HT29-MTX Cells. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.A.; Wang, X. Use of bacterial co-cultures for the efficient production of chemicals. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 53, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Sagastume, F.; Bengtsson, S.; De Grazia, G.; Alexandersson, T.; Quadri, L.; Johansson, P.; Magnusson, P.; Werker, A. Mixed-culture polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production integrated into a food-industry effluent biological treatment: A pilot-scale evaluation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, G.; Afzal, M.; Anwar, F.; Tahseen, R.; Khalid, Z.M. Biodegradation of kerosene in soil by a mixed bacterial culture under different nutrient conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2008, 61, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shong, J.; Jimenez Diaz, M.R.; Collins, C.H. Towards synthetic microbial consortia for bioprocessing. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chian, S.K.; Mateles, R.I. Growth of mixed cultures on mixed substrates. I. Continuous culture. Appl. Microbiol. 1968, 16, 1337–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G. Studying the dynamics of microbial populations during food fermentation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goers, L.; Freemont, P.; Polizzi, K.M. Co-culture systems and technologies: Taking synthetic biology to the next level. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, F.; Leventhal, G.E.; Spalinger, M.R.; Anthamatten, L.; Rogalla von Bieberstein, P.; Menzi, C.; Reichlin, M.; Meola, M.; Rosenthal, F.; Rogler, G.; et al. Co-cultivation is a powerful approach to produce a robust functionally designed synthetic consortium as a live biotherapeutic product (LBP). Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2177486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geria, M.; Caridi, A. Methods to assess lactic acid bacteria diversity and compatibility in food. Acta Aliment. 2014, 43, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierings, L.R.; Braga, C.M.; da Silva, K.M.; Wosiacki, G.; Nogueira, A. Population dynamics of mixed cultures of yeast and lactic acid bacteria in cider conditions. Braz. Arch. Biotechnol. Technol. 2013, 56, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maru, B.T.; López, F.; Kengen, S.W.M.; Constantí, M.; Medina, F. Dark fermentative hydrogen and ethanol production from biodiesel waste glycerol using a co-culture of Escherichia coli and Enterobacter sp. Fuel 2016, 186, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirinutsomboon, B.; Delwiche, M.J.; Young, G.M. Attachment of Escherichia coli on plant surface structures built by microfabrication. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 108, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad-Tahir, Z.; Alocilja, E.C. A Disposable Biosensor for Pathogen Detection in Fresh Produce Samples. Biosyst. Eng. 2004, 88, 145–151, Corrigendum in Biosyst. Eng. 2006, 93, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Karim, A.; Mishra, P.; Dubowski, J.J.; Yousuf, A.; Sarmin, S.; Khan, M.M.R. Microbial synergistic interactions enhanced power generation in co-culture driven microbial fuel cell. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosero-Chasoy, G.; Rodríguez-Jasso, R.M.; Aguilar, C.N.; Buitrón, G.; Chairez, I.; Ruiz, H.A. Microbial co-culturing strategies for the production high value compounds, a reliable framework towards sustainable biorefinery implementation—An overview. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 321, 124458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanitá Lima, M.; Coutinho de Lucas, R. Co-cultivation, Co-culture, Mixed Culture, and Microbial Consortium of Fungi: An Understudied Strategy for Biomass Conversion. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Bao, M.; Su, H.; Xu, P. Microbial Production of Hydrogen by Mixed Culture Technologies: A Review. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 15, e1900297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutinho, T.J., Jr.; Panagides, J.C.; Biggs, M.B.; Medlock, G.L.; Kolling, G.L.; Papin, J.A. Novel co-culture plate enables growth dynamic-based assessment of contact-independent microbial interactions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, A.L.; Weuster-Botz, D. Population heterogeneity in microbial bioprocesses: Origin, analysis, mechanisms, and future perspectives. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 889–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basharat, Z.; Yasmin, A. Survey of compound microsatellites in multiple Lactobacillus genomes. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015, 61, 898–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi Fru, E.; Ofiţeru, I.D.; Lavric, V.; Graham, D.W. Non-linear population dynamics in chemostats associated with live–dead cell cycling in Escherichia coli strain K12-MG1655. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 89, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofiţeru, I.D.; Ferdeş, M.; Knapp, C.W.; Graham, D.W.; Lavric, V. Conditional confined oscillatory dynamics of Escherichia coli strain K12-MG1655 in chemostat systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 94, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreselassie, N.A.; Antoniewicz, M.R. 13C-metabolic flux analysis of co-cultures: A novel approach. Metab. Eng. 2015, 31, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isopencu, G.; Tanase, A.; Josceanu, A.-M.; Lavric, V. Influence of the Operating Parameters on the E. coli BL21 (DE3) Growth in Fedbatch Bioreactor. Rev. Chim. 2014, 65, 1511–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Inglin, R.C.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Meile, L.; Lacroix, C.; Meile, L. High-throughput screening assays for antibacterial and antifungal activities of Lactobacillus species. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 114, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, Y.-C.; Xue, C.; Ng, I.S. Symbiosis culture of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG using lactate utilization protein YkgG. Process Biochem. 2023, 126, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, J.; Iahtisham Ul, H.; Nayik, G.A.; Ramniwas, S.; Mugabi, R.; Ali Alharbi, S.; Ansari, M.J. Studies on the growth of Lactobacillus reuteri, Bifidobacterium and Escherichia coli as affected by prebiotic extracted from citrus peel. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 783–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, F.; Pérez-Carrasco, V.; Rodríguez-Granger, J.; Sampedro-Martínez, A.; García-Salcedo, J.A.; Navarro-Marí, J.M. Differences between bloodstream infections involving Gram-positive and Gram-negative anaerobes. Anaerobe 2023, 81, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, N.C.; Manetsberger, J.; Benomar, N.; Abriouel, H.; Gombossy de Melo Franco, B.D. Co-cultures of lactic acid bacteria from Brazilian foods as inhibitors of Listeria monocytogenes and Escherichia coli O157:H7 biofilm formation. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Aquino, S.; Maldonado Simán, E.J.; Miranda-Romero, L.A.; Alarcón Zuñiga, B. Meat Native Lactic Acid Bacteria Capable to Inhibit Salmonella sp. and Escherichia coli. Biocontrol Sci. 2020, 25, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiousi, D.E.; Panopoulou, M.; Pappa, A.; Galanis, A. Lactobacilli-host interactions inhibit Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli-induced cell death and invasion in a cellular model of infection. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredua-Agyeman, M.; Stapleton, P.; Gaisford, S. Growth assessment of mixed cultures of probiotics and common pathogens. Anaerobe 2023, 84, 102790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.K.; Khanaqa, H.H.; Izzatul, M. Purification and Characterization of Surlactin Produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Al-Anbar Med. J. 2010, 8, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfir, M.; Callewaert, R.; Cornea, P.C.; De Vuyst, L. Production kinetics of acidophilin 801, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus IBB 801. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2000, 190, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavric, V.; Graham, D.W. Birth, growth and death as structuring operators in bacterial population dynamics. J. Theor. Biol. 2010, 264, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roy, K.; Clement, L.; Thas, O.; Wang, Y.; Boon, N. Flow cytometry for fast microbial community fingerprinting. Water Res. 2012, 46, 907–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, K. Application of Flow Cytometry for Enumerating Individual Bacterial Cultures from a Mixed Culture System. Master’s Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberger, R.; Arents, J.; Dekker, H.L.; Pridmore, R.D.; Gysler, C.; Kleerebezem, M.; de Mattos, M.J. H(2)O(2) production in species of the Lactobacillus acidophilus group: A central role for a novel NADH-dependent flavin reductase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooj, A.K.; Kimura, Y.; Buddington, R.K. Metabolites produced by probiotic Lactobacilli rapidly increase glucose uptake by Caco-2 cells. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Altermann, E.; Hoover-Fitzula, R.L.; Cano, R.J.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Identification and inactivation of genetic loci involved with Lactobacillus acidophilus acid tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5315–5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Callewaert, R.; Crabbé, K. Primary metabolite kinetics of bacteriocin biosynthesis by Lactobacillus amylovorus and evidence for stimulation of bacteriocin production under unfavourable growth conditions. Microbiology 1996, 142, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, M.; Shimizu, K.; Nomoto, K.; Tanaka, R.; Hamabata, T.; Yamasaki, S.; Takeda, T.; Takeda, Y. Inhibition of in vitro growth of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 by probiotic Lactobacillus strains due to production of lactic acid. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 68, 135–140, Erratum in Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 74, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Wang, P.; Sun, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, X. Interaction of Type IV Toxin/Antitoxin Systems in Cryptic Prophages of Escherichia coli K-12. Toxins 2017, 9, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuchowska, K.; Tracewska, A.; Depka-Radzikowska, D.; Bogiel, T.; Włodarski, R.; Bojko, B.; Filipiak, W. Profiling of Volatile Metabolites of Escherichia coli Using Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelwahed, E.K.; Hussein, N.A.; Moustafa, A.; Moneib, N.A.; Aziz, R.K. Gene Networks and Pathways Involved in Escherichia coli Response to Multiple Stressors. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nochebuena-Pelcastre, X.; Álvarez-Contreras, A.K.; Hernández-Robles, M.F.; Natividad-Bonifacio, I.; Parada-Fabián, J.C.; Quiñones-Ramirez, E.I.; Vazquez-Quiñones, C.R.; Vázquez Salinas, C. Development of a low pollution medium for the cultivation of lactic acid bacteria. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Hai, D.; Wei, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, P. The Functional Roles of Lactobacillus acidophilus in Different Physiological and Pathological Processes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent for Determination of Reducing Sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, D.J.; Shanmuganathan, S.; Mortimer, F.C.; Gant, V.A. A fluorescent Gram stain for flow cytometry and epifluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2681–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Media | KS-X/ (gL−1) | Yxs × 103/ (g g−1) | µmax/ h−1 | kS/ h−1 | kd × 105/ h−1 | FOB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | SSCM | 79.8 ± 3.2 | 67 ± 4.1 | 1.02 ± 0.047 | 0.211 ± 0.001 | 480 ± 29 | (112 ± 5.6) × 10−3 |

| MRS | 70.8 ± 3.4 | 78 ± 3.8 | 1.88 ± 0.08 | (74 ± 3.7) × 10−3 | 2.32 ± 0.12 | (140 ± 6.5) × 10−3 | |

| L. acidophilus | SSCM | 1.12 × 104 ± 540 | 63 ± 3.1 | 147 ± 7.6 | 0.827 ± 0.038 | (9.72 ± 0.5) × 10−2 | 0.092 ± 0.048 |

| MRS | 883 ± 43.5 | 92 ± 4.3 | 4.38 ± 0.21 | 0.065 ± 0.004 | (3.68 ± 0.18) × 10−2 | 0.095 ± 0.051 | |

| E. coli and L. acidophilus | MRS | (20 ± 0.9) × 10−4 | (6.18 ± 0.34) × 103 | (87 ± 4.3) × 10−3 | (14 ± 0.66) × 10−2 | 1.61 ± 0.78 | 0.29 ± 0.014 |

| (706 ± 35) × 10−3 | 3.6 ± 0.18 | (63.9 ± 4) × 10−3 | 4.54 ± 0.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isopencu, G.; Gogulancea, V.; Lavric, V.; Banu, I. Mathematical Modeling of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus acidophilus Growth Based on Experimental Mixed Batch Cultivation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311493

Isopencu G, Gogulancea V, Lavric V, Banu I. Mathematical Modeling of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus acidophilus Growth Based on Experimental Mixed Batch Cultivation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311493

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsopencu, Gabriela, Valentina Gogulancea, Vasile Lavric, and Ionut Banu. 2025. "Mathematical Modeling of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus acidophilus Growth Based on Experimental Mixed Batch Cultivation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311493

APA StyleIsopencu, G., Gogulancea, V., Lavric, V., & Banu, I. (2025). Mathematical Modeling of Escherichia coli and Lactobacillus acidophilus Growth Based on Experimental Mixed Batch Cultivation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311493