1. Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane vesicles secreted by all cell types and circulating in numerous biological fluids of the human body. EVs act as messengers between cells, transporting nucleic acids and proteins [

1]. Therefore, EVs can be involved in various physiological and pathophysiological processes, such as immune responses [

2], tumor progression [

3], viral infections [

4], and others [

5]. Given that all EVs are composed of proteins and lipids reflecting the biochemical composition and the status of the parent cell, as well as the high amount of EVs present in biological fluids, they are considered promising biomarkers of various diseases, including cancer [

6]. In this regard, the isolation of tumor-derived EVs followed by the analysis of either EVs’ membrane proteins or EVs’ cargo would make a significant contribution both for understanding their functions and finding the way to use them in the development of minimally invasive diagnostic tools [

7,

8].

Methods for studying EVs are constantly evolving; however, obtaining purified and biologically active EVs from biological samples for downstream analysis remains a significant challenge. Ultracentrifugation is the most frequently used method for enriching EVs from various biological sources, such as cell culture medium, urine, and blood plasma [

9]. In addition, ultrafiltration and sedimentation by polymers are also used to isolate EVs from various biological samples [

10,

11]. These methods, nevertheless, do not provide sufficient amounts and purity of EVs, require trained personnel, and long operation time [

12]. The disadvantages can be somewhat overcome by using the size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) method. The SEC method is convenient, inexpensive, and avoids significant protein contamination or EV damage [

13]. At the same time, for the molecular content discovery of EVs or direct quantification of EVs, all the above methods should be followed by additional analysis using Western blotting (WB), polymerase chain reaction, or mass spectrometry, which in turn require highly qualified specialists, long-term operation, and costly equipment.

Flow cytometry (FC) is an established method that is widely used for routine quantitative and qualitative analysis of cells; therefore, it is also considered a promising method for EVs’ study [

14]. However, the application of FC for EVs’ analysis is limited because EVs with a diameter below 300 nm are not efficiently discriminated from the background signal in scattering modes [

15]. The sensitivity of FC in EVs analysis can be improved by an optimized configuration of FC equipment [

16] or through double labeling of EVs with protein- and lipid-specific dyes [

13,

17]. However, in the meantime, the above protocols require manual hardware adjustment and calibration of the FC before use, as well as a time-consuming labeling step and further EV purification from the unbound dye.

On the other hand, isolation of EVs using magnetic beads combined with conventional flow cytometry (FC) analysis is an attractive technique for the development of innovative liquid biopsy based on EV biomarker detection [

18,

19]. First, EVs secreted by tumor tissues can be captured from the biological samples using magnetic beads conjugated with appropriate ligands which are capable of either specifically or non-specifically interacting with EVs’ surface receptors [

20]. Second, the trapped EVs can be purified by multiple washes, thus ensuring a fraction of EVs free from non-vesicular particles and contaminant proteins. A bead-based platform is highly efficient in terms of purity, providing a higher concentration of exosome-specific proteins compared to common isolation strategies [

21]. Finally, analysis of EV membrane proteins can be performed immediately on the bead surface using flow cytometry (FC) and commercially available fluorescently labeled antibodies, aptamers, and peptides [

22]. In this regard, platforms based on magnetic beads are beneficial both for isolation, purification, and molecular analysis of EVs, offering vast opportunities for the detection of a wide range of tumor biomarkers.

Generally, affinity capture is the most common method for isolating EVs using magnetic beads [

22]. Beads conjugated with vector molecules such as antibodies, peptides, or aptamers targeted to EVs membrane markers, such as tetraspanins CD9, CD63, CD81, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), or the phosphatidylserine receptor (Tim4) [

23] are applied for isolation of the total population of EVs. However, the isolation of distinct EV populations is often limited due to the high cost or poor reproducibility of the kits. Alternatively, EVs can be captured based on electrostatic attraction [

24], dipole–dipole interaction [

25,

26], or hydrogen bonding [

27]. In our previous work, we demonstrated that tannic acid-coated magnetic beads had a high efficiency in capturing EVs (60%) from solutions with low protein content, primarily cell culture medium [

28]. TA is a natural organic polyphenolic compound containing ten molecules of gallic acid. The robust EVs’ interaction with TA is attributed to the formation of a cation-p complex between the galloyl ring and the quaternary amine group of phospholipid membranes, in addition to hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction. The size and morphology of EVs in the supernatant and eluate did not change following beads’ adsorption. Furthermore, non-bound proteins can be removed from the beads’ surfaces, while EVs remain adsorbed. Considering these characteristics, tannic acid-coated beads offer a promising method for purifying and analyzing EVs.

In this study, we applied tannic acid-functionalized superparamagnetic beads (TASPMB) for enrichment of EVs from conditioned media of two humans’ colorectal cancer HT29 and breast cancer SKBR3 cell cultures. Subsequently, the captured EVs by TASPMB were analyzed using conventional flow cytometry through labeling of CD63 and EpCAM proteins in the plasma membrane of EVs. The approach demonstrated in our study can be useful for basic research that requires the rapid and reliable isolation and molecular profiling of EVs.

3. Discussion

This study introduces a novel technique that employs tannic acid-coated superparamagnetic beads in combination with conventional flow cytometry for the efficient isolation and characterization of membrane proteins in extracellular vesicles. The approach was first verified on EVs, which were pre-isolated from human cancer cell lines and a colorectal cancer patient by SEC. We optimized EV:TASPMB ratio and the buffer composition to obtain a reliable fluorescence intensity for the identification of EV membrane proteins. These findings allowed us to successfully test for phenotyping of EVs isolated from cell culture medium by TASPMB without SEC enrichment. The proposed method capitalizes on the unique properties of tannic acid, which forms robust, non-specific bonds with phospholipids and proteins that make up the EV membrane, resulting in the formation of a highly stable complex of TASPMB and EV. A high association between EV and TASPMB appears to be advantageous when washing the TASPMB-EV complex, which likely results in additional purification of trapped EVs. This, in turn, liberates binding sites on the EV membrane and enables efficient molecular profiling of EVs using dye-labeled aptamers. In our previous study, we demonstrated that the size of EVs in both the supernatant and the eluate remained unchanged, suggesting that EVs adsorbed onto magnetic beads are purified from the proteins contained in the samples [

28]. Therefore, we believe that contaminating protein can be washed off the surface of the beads before flow cytometry analysis.

Despite the lack of specific trapping of EVs through individual proteins, this approach achieves a remarkable capture efficiency (~72%), enabling the precise identification and quantification of membrane-associated proteins by flow cytometry. Compared with existing affinity-based capture systems, the tannic acid-based coating has several advantages: it is cost-effective, simpler to implement, and scalable using the layer-by-layer assembly method. Additionally, the surface modification can be conducted rapidly on-site without requiring specialized equipment, making TASPMB suitable for clinical applications.

However, while promising, this platform requires further optimization before it can be widely adopted. Current limitations include weak fluorescent signals when detecting membrane-bound proteins in real samples, necessitating the development of improved experimental protocols, such as optimized buffer compositions and enhanced labeling strategies. Buffer compositions play an important role in maintaining optimal pH and ionic strength for efficient binding during the experiment. Additionally, an optimal buffer composition helps preserve the integrity of bound ligands and prevents degradation of proteins or magnetic beads through aggregation. Potassium is one of the main cations in the cellular environment and can significantly affect the structure of nucleic acids, including RNA aptamers. Potassium can stabilize certain secondary structures, which can lead to a decrease in the affinity of the aptamer for the target molecules. In our studies, we used buffered solutions without potassium, which makes it possible to eliminate undesirable conformational changes in aptamers and ensure reliable binding of vesicles to membrane proteins. We also added Tween-20 due to two reasons. Tween-20 acts as a detergent, reducing the surface tension of solutions. This reduces the likelihood of non-specific protein adsorption on the surface of magnetic bits. The use of small concentrations of Tween-20 (usually about 0.01–0.1%) reduces the aggregation of macromolecules. This increases the reproducibility and reliability of the analysis. Enhanced labeling strategies require simpler and faster protocols, which will decrease the cost and duration of experiments. Modification of the surface of magnetic beads with tannic acid via simple and cost-effective LbL method for EVs capture is an attractive new strategy as the final step in sample preparation before labeling and analysis. Moreover, further optimization studies for clinical samples should be concentrated on the following points: (i) dilute versus concentrated plasma samples due to presence of high amounts of immunoglobulins and other vesicles. It is assumed that working with diluted samples can avoid absorbance of contaminating proteins on the beads and thus increase the efficiency of EVs’ interaction with the platform; (ii) variation in the amount of EVs released by each patient due to their particular pathophysiological conditions. Addressing these hurdles could improve the sensitivity and reproducibility of analyses, ultimately facilitating the reliable and accurate detection of biomarkers within liquid biopsies derived from EV populations.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4, HIMEDIA, Thane, India). Ethanol (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Lipophilic carbocyanine dye 3,3′dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine (DiO, Lumiprobe, Westminster, MD, USA). 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Uranyl acetate dihydrate (Sisco Research Laboratories, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India). Bovine serum albumin (BSA, ≥96%, ~66 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Tannic acid (TA, residue on ignition ≤0.5%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). SDS-PAGE gel, nitrocellulose membranes, and blocking buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Primary monoclonal antibody specific to CD63 (Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA, Rabbit mAb #10112), CD81 (Cell Signaling Technology, Rabbit mAb #56039), CD9 (Cell Signaling Technology, Rabbit mAb #13174), Alix (Cell Signaling Technology, Rabbit mAb #92880), Flotillin-1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Rabbit mAb #18634). Primary monoclonal antibody anti-EpCAM (PrimeBioMed, Moscow, Russia, VU-1D9, Mouse Ab, #10-310017-01). Primary antibodies specific to apolipoprotein A1 (RAH Laa, Imtek, Moscow, Russia), B (RAH Lbb, Imtek) and IgG (MGH Igg, Imtek). Primary antibody specific to Calnexin (Cloud-Clone Corp., Katy, TX, USA, Rabbit #PAA280Hu01). Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP against rabbit immunoglobulin (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, #1706515). Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP against mouse immunoglobulin (Sorbent, Moscow, Russia, Mouse Ab #1069). Cyanine5 NHS ester (Cy5)-labeled anti-EpCAM aptamer (5′-ag-tga-cgc-agc-atg-cgg-cac-aca-ctt-cta-tct-ttg-cgg-aac-tcc-tgc-gg-(Cy5), Synthol, Moscow, Russia). Cyanine5 NHS ester (Cy5)-labeled anti-CD63 aptamer (5′-ta-acc-acc-cca-cct-cgc-tcc-cgt-gac-act-aat-gct-aat-tcc-aa-(Cy5), Synthol, Russia). BCA protein assay kit (FineTest, Wuhan, China). JetSpin™ Centrifugal Filter (15 mL, 100,000 MWCO and 5 mL, 50,000 MWCO, Jet Bio-Filtration, Guangzhou, China). Size-exclusion chromatography PURE-EVs (HBM-PEV-5) and mini PURE-EVs (HBM-mPEV-10) columns (HansaBioMed, Tallinn, Estonia). Protein LoBind tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Deionized water purified on a Millipore Milli-Q system (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with resistivity 18 MΩ·cm was used in the experiments. All chemicals were used without further purification.

4.2. Preparation of Superparamagnetic Beads

4.2.1. Synthesis of Hydrophobic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

A mixture of 5 mmol of iron(II) chloride dihydrate and 10 mmol of iron(III) chloride hexahydrate in 50 mL of deionized water was slowly added to 200 mL of 1 M ammonia solution under vigorous stirring at 80 °C in an argon atmosphere. Then, 1 mL of oleic acid was added, and the stirring continued for 15 min. The black precipitate was separated by a neodymium magnet and washed several times with distilled water and acetone. The colloid was then redispersed in chloroform, forming a total concentration of iron oxide of 10 mg/mL.

4.2.2. Synthesis of Silica-Coated Superparamagnetic Beads

The emulsion droplet solvent evaporation method was employed for the fabrication of iron oxide clusters, as described in the protocol reported in [

36], with minor modifications. An amount of 1 mL of hydrophobic iron oxide nanoparticles was added to 1 mL of 60 mM myristyltrimethylammonium bromide solution in deionized water and sonicated for 5 min. Then the mixture was transferred into a three-necked flask and heated at 60 °C for one hour with argon purification to evaporate the organic solvent. The prepared clear solution of iron oxide clusters is then redispersed in 3 mL of 3 mM poly(vinylpyrrolidone) solution in ethylene glycol and stirred for 5 min. The resulting polymer-capped iron oxide clusters were precipitated with a magnet and washed three times with deionized water. The silica shells were synthesized by the standard Stöber method. An amount of 10 mg of iron oxide clusters was transferred to 50 mL of 90% ethanol containing 0.02 mmol of ammonia, sonicated for 5 min, followed by adding 0.1 mL of tetraethoxysilane. The reaction mixture was stirred vigorously at room temperature for 1 h. The black precipitate of silica-coated iron oxide clusters was then collected by a magnet and washed thrice with ethanol and water.

4.2.3. Functionalization of Silica-Coated Iron Oxide Clusters with Amino Groups

An amount of 10 mg of silica-coated iron oxide clusters was resuspended in 30 mL of ethanol, and then 0.5 mL of APTES was added under an argon atmosphere with vigorous stirring. The resulting mixture was then kept at 60 °C for 6 h. After the reaction had stopped, the beads were washed three times with ethanol to remove.

4.3. Deposition of Tannic Acid on Amino-Functionalized Silica-Coated Superparamagnetic Beads

An amount of 1.6 mL of BSA water solution (2 mg/mL) was added to 0.2 mL aqueous suspension of amino-functionalized silica-coated iron oxide clusters (1 mg), followed by agitation on a shaker for 15 min. The clusters were then washed three times with water to remove unbound protein molecules. Then, 1.6 mL of TA water solution (2 mg/mL) was added to the cluster suspension and agitated for another 15 min, followed by washing three times with water. The deposition of BSA and TA was repeated five times, which resulted in the following composition on the cluster surface: Clusters/(BSA/TA)5. The clusters were kept in water at 4 °C for further use.

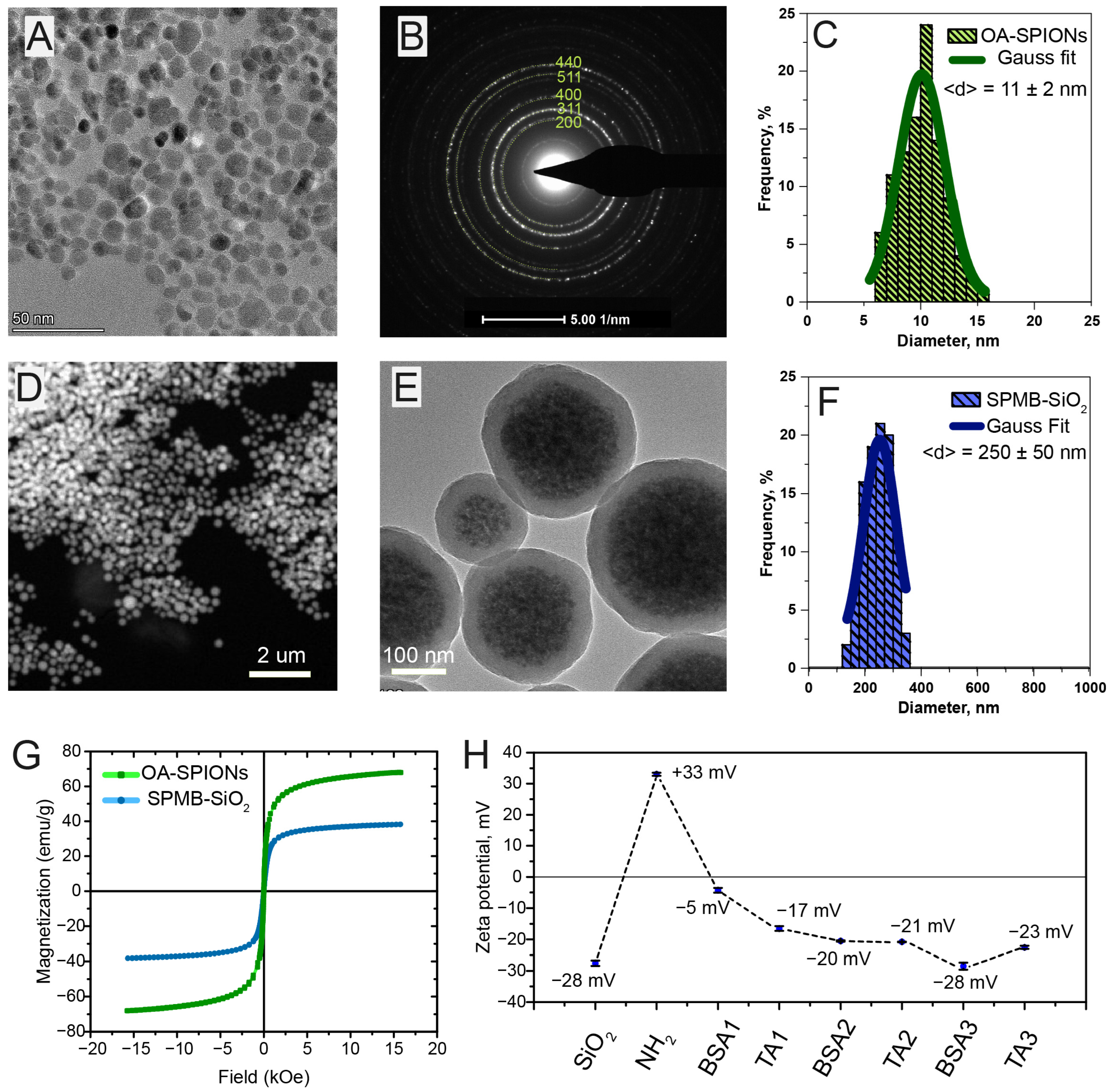

4.4. Characterization of Superparamagnetic Beads (SPMB)

To characterize the SPMB during surface functionalization with amino groups and deposition of polyelectrolytes, several methods were used. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the nanoparticles were obtained using a Quattro microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using a Titan microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) equipped with an EDX attachment (USA). Energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDS) was performed using a transmission electron microscope equipped with attachments for elemental analysis using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (Super-X EDX detector) and electron energy loss spectroscopy (Quantum 965) methods. Zeta potential was determined by electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) on a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Panalytical, Westborough, MA USA).

4.5. Isolation of EVs from Cell Culture and Blood Plasma

In the present study, EVs were derived from human breast cancer SKBR3 cell lines and human colorectal cancer HT29 cell lines. Cell lines were grown in 175 cm2 culture flasks in DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% L-Glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.1% gentamicin. After reaching a confluence of 90–100%, the culture medium was replaced with a medium without FBS for 48 h before the collection of EVs. After 48 h, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 400× g for 10 min to remove dead cell debris. The samples of culture medium were frozen and stored at −20 °C in 50 mL Eppendorf tubes. Before EV isolation by ultrafiltration (UF) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) methods, cell culture medium (~90 mL volume for each cell line) was sequentially centrifuged 300× g for 10 min, 1200× g for 20 min to remove aggregates, concentrated, and preliminary purified by using JetSpin™ Centrifugal 100 kDa filter. To isolate EVs, 500 μL of concentrated cell culture medium was loaded in the precleaned mini PURE-EVs SEC column, and five 100 μL fractions were collected according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

The blood sample was a donation from N.N. Blokhin National Medical Research Center of Oncology within protocol #9 dated 18.09.2023. Cells were removed from plasma by centrifugation at 1000× g and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was then centrifuged again at 2000× g and 4 °C to remove platelets, aliquoted into 2 mL tubes, and stored at −20 °C before EV isolation. To isolate EVs from plasma, 1 mL of thawed sample was diluted in 1 mL of DBPS and centrifuged for 30 min at 4500× g at 4 °C, and 2 mL of supernatant was loaded into the prepared PURE-EVs SEC column. Three 500 μL fractions enriched in EVs were collected according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Samples of EVs derived from cell cultures and plasma were stored at −20 °C in protein LoBind tubes until further analysis.

HT29 EVs were isolated four times from four HT29 cell line samples, SKBR3 EVs were obtained three times from three SKBR3 cell line samples, and plasma EVs were isolated twice from 2 mL crude plasma of patients.

4.6. Conjugation of EVs with Lipophilic Dye

Fluorescently labeled EVs were obtained using the following procedure: 200 μL of isolated EVs from HT29 cell culture medium (average number of vesicles 2 × 1010 particles/mL) in DPBS was loaded in a protein LoBind tube and two μL of DiO dye (2 uM in a DMSO:PBS mixture (1:1)) was injected to the tube followed by incubation of the tube in a shaker at RT for 5 min. To remove dye excess, the sample was then loaded in the prepared SEC column and five 100 μL fractions collected according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. DiO-labeled EVs were stored at −4 °C in LoBind tubes until further analysis.

4.7. Characterization of EVs

To evaluate the efficiency and purity of isolated EVs, EV samples were characterized by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), analysis of total protein with bicinchoninic acid (BCA), and Western blotting (WB).

Before TEM imaging, samples of isolated EVs were transferred to deionized water to minimize the amount of salt crystals formed upon drying and concentrated to a final volume of 200–250 μL by using JetSpin™ Centrifugal 50 kDa filter. A carbon grid was treated on a glow discharge system to make the film hydrophilic. Then, the grid was incubated with a droplet (~20 μL) of the EV sample for 10 s. The excess of the EV sample was removed by blotting the grid perpendicular to the filter paper. The grid was then incubated on a drop of uranyl acetate water solution (1.5 mg/mL) for 30 s, followed by blotting the stain away using filter paper and drying the grid for 10 min before imaging. The grid was fixed on the TEM sample holder, and EVs were analyzed at magnification ranging from 60,000 to 340,000 times by using Titan Themis Z TEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Protein amount in EV samples was determined by using the micro BCA protein assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol. EV samples (100 μL) were incubated with an equal volume of the working reagent for 2 h at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 562 nm by using an Infinite Nano+ plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland). The analysis was performed for three replicates.

The size and concentration of EVs were estimated by using a ZetaView® PMX420-QUATT instrument (Particle Metrix, Inning am Ammersee, Germany). The laser wavelength used in scatter and fluorescent modes was 488 nm, and the filter wavelength used in fluorescent mode was 520 nm. Samples with isolated EVs were diluted 1:80–1:2000 in DPBS before video recording. The recording was repeated five times for each sample. The videos were analyzed using ZetaView software (version 8.05.14 SP7) to determine the size distribution of EVs, their mean, and EV concentration.

For Western blotting, EV samples were separated on the SDS-PAGE gel and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were washed with PBST (0.1% Tween-20 in PBS) and blocked for 30 min at RT in 5% nonfat milk (for Alix or Flotillin-1) or 5% BSA (for CD63, CD9, CD81, Calnexin or EpCAM) in PBST. The presence or absence of CD63, CD9, CD81, Calnexin, Alix, Flotillin-1, and EpCAM was determined on separate membranes, which were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer while shaking gently. In the case of ApoA, ApoB1 and IgG plasma used for isolation of EVs was first diluted in PBS to achieve total protein concentration (Protein A280) the same as plasma EV samples. A 4% gel was used for ApoB, while 15% gel was used for ApoA and IgG. Primary antibodies used for ApoA, ApoB1, and IgG analysis were diluted 1:1000. After five washes, 5 min each, with PBST solution, membranes were incubated in a blocking buffer containing peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies diluted 1:2500 (1:5000 in case of ApoA, ApoB1, and IgG) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed five times with PBST and developed using SuperSignal™ West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the MicroChemi 4.2 Imaging System (DNR Bio Imaging System, Jerusalem, Israel).

An amount of 100 μL of EVs-DiO sample was added to a 96 plate, and fluorescence spectrum was acquired at 430 nm excitation wavelength in emission wavelength interval from 475 to 600 nm with emission wavelength step size of 2 nm by using an Infinite Nano+ plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland). EV fractions from 8 to 14 were placed separately (2 μL) to a nitrocellulose membrane and dried before measurements. Measurements were performed at excitation and emission wavelengths of 460 nm and 520 nm by using the IVIS Spectrum CT imaging system (PerkinElmer, Shelton, CT, USA).

4.8. Capture of EVs by Tannic Acid-Coated Superparamagnetic Beads (TASPMB) and Detection of EV Membrane Proteins

First, SPMB were incubated with DiO-stained EVs, varying the ratio of SPMB and EV-DiO (1:25; 1:10; 1:5) for 1 h on a thermoshaker at 25 °C using 800 rpm. After the incubation, MB with bound EV-DiO were collected using a magnetic stand, and the supernatant containing unbound EV-DiO was transferred to a new protein, LoBind, for determining their concentration using the NTA method.

To estimate the amount of bound sEVs on the surface of tannic acid-coated beads, we calculated the capture efficiency (CE) using the following expression:

where N

int is the initial concentration of sEVs mixed with tannic acid-coated beads, and N

sup corresponds to the number of sEVs determined in the supernatant after the collection of SPMB. The N

int and N

sup concentrations of sEVs were determined using the nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) method.

Subsequently, TASPMB with attached EV-DiO was washed thrice with DPBS and fluorescence signal was immediately acquired from the TASPMB-EV-DiO complex by using CytoFLEX flow fluorescence cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The fluorescent signal was recorded in the FITC channel (ex: 488 nm; em: 520 nm).

To perform profiling of EVs pre-isolated by SEC from cell culture medium and plasma samples, 270 μL of EVs and 30 μL of TASPMB were mixed in a new protein LoBind tube, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h on a thermoshaker at 25 °C using 800 rpm. After the incubation, MB with trapped EVs were collected on a magnetic rack, and the supernatant was taken and transferred to a new protein LoBind tube to determine unbound EVs by using the NTA method. SPMB-EV complex was washed three times with DPBS and then resuspended in 400 μL of a buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.01% Tween-20, and 100 μL of either anti-EpCAM aptamer (1 pM) or anti-CD63 aptamer (1 pM) was added to TASPMB-EV complex. The mixture was incubated for 30 min on a thermoshaker at 800 rpm and room temperature (RT). TASPMB-EV-Aptamer complex was collected on a magnetic stand, and the complex was washed several times with a buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.01% Tween-20 to remove unbound aptamer molecules. The MB-EV-Aptamer complex was resuspended in 500 μL of a buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) and analyzed by using CytoFLEX cytometer.

To implement molecular profiling of EVs directly from cell culture medium, 20 μL of MB was mixed with 180 μL of conditioned media of SKBR3 or HT29 cell cultures and incubated on a thermoshaker at 25 °C using 800 rpm. After the incubation, TASPMB-EVs complex was washed thrice with DPBS and transferred to a 400 μL buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.01% Tween-20. Then, 100 μL of either anti-EpCAM aptamer (1 pM) or anti-CD63 aptamer (1 pM) was added to the TASPMB-EV complex, and the mixture was incubated on a thermoshaker at 800 rpm and room temperature (RT). After 30 min of incubation, the TASPMB-EV-Aptamer complex was collected on a magnetic stand and thoroughly washed in a buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.01% Tween-20 to purify it from unbound aptamer molecules. The SPMB-EV-Aptamer complex was transferred to a 500 μL buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4) and measured on the CytoFLEX cytometer. The fluorescent signal from Cy5 labeled anti-EpCAM and anti-CD63 aptamers was captured in the APC channel (ex: 638 nm, em: 660 nm).