Altered Co-Expression Patterns of Mitochondrial NADH-Dehydrogenase Genes in the Prefrontal Cortex of Rodent ADHD Models

Abstract

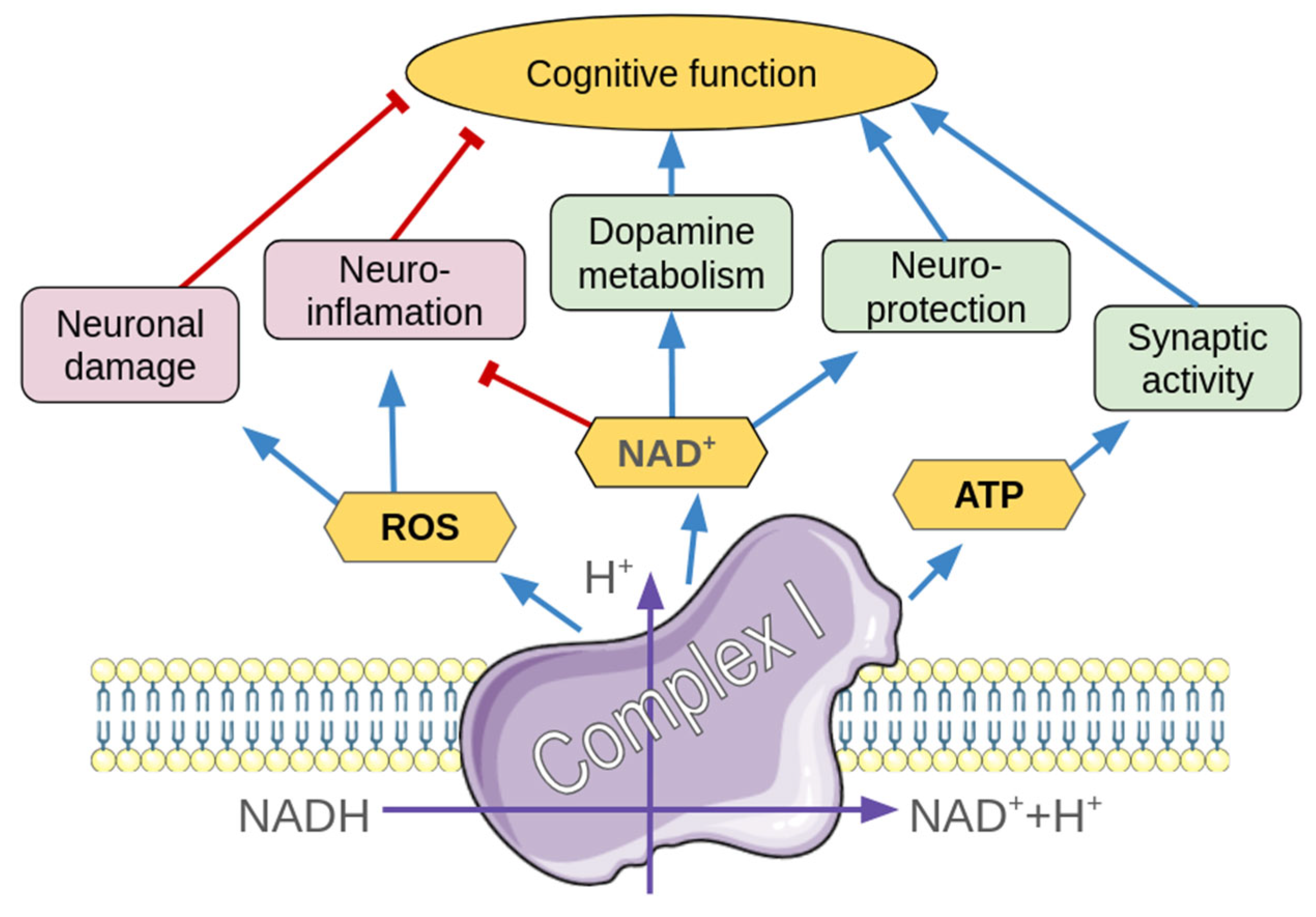

1. Introduction

2. Results

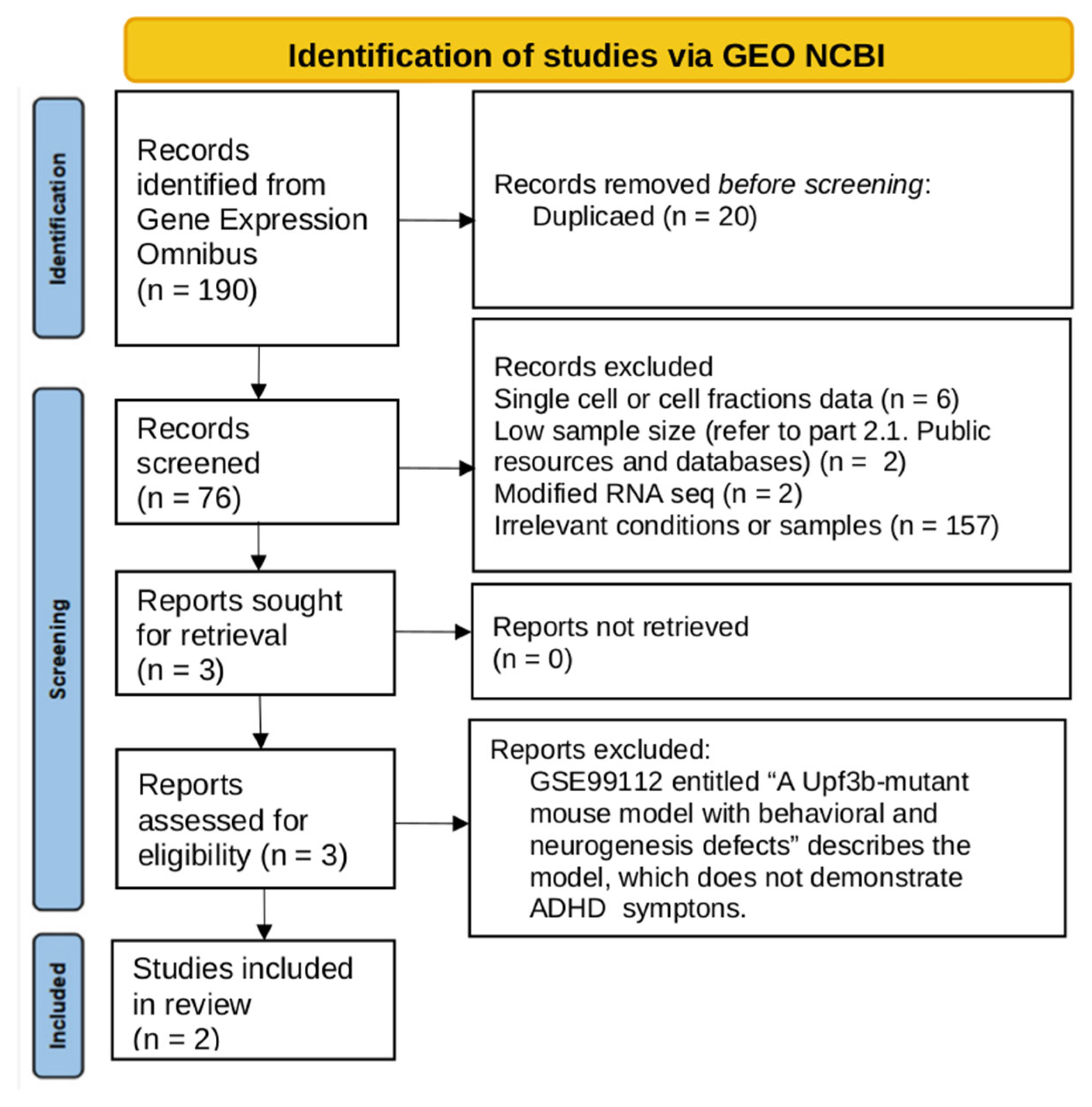

2.1. Data Search and Inclusion

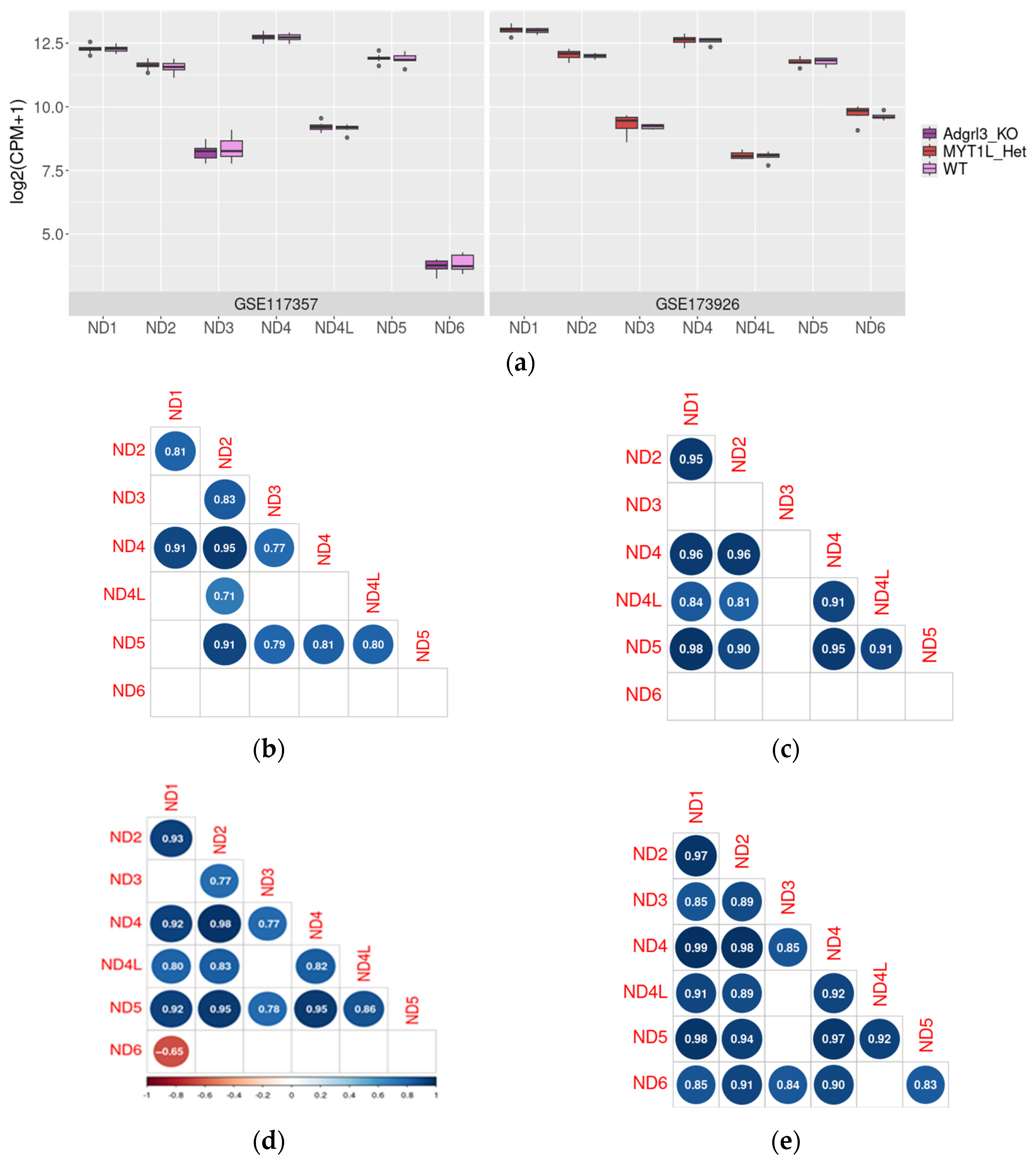

2.2. ND1–6 Expression in the Prefrontal Cortex in Mouse Models of ADHD RNA-Seq Data

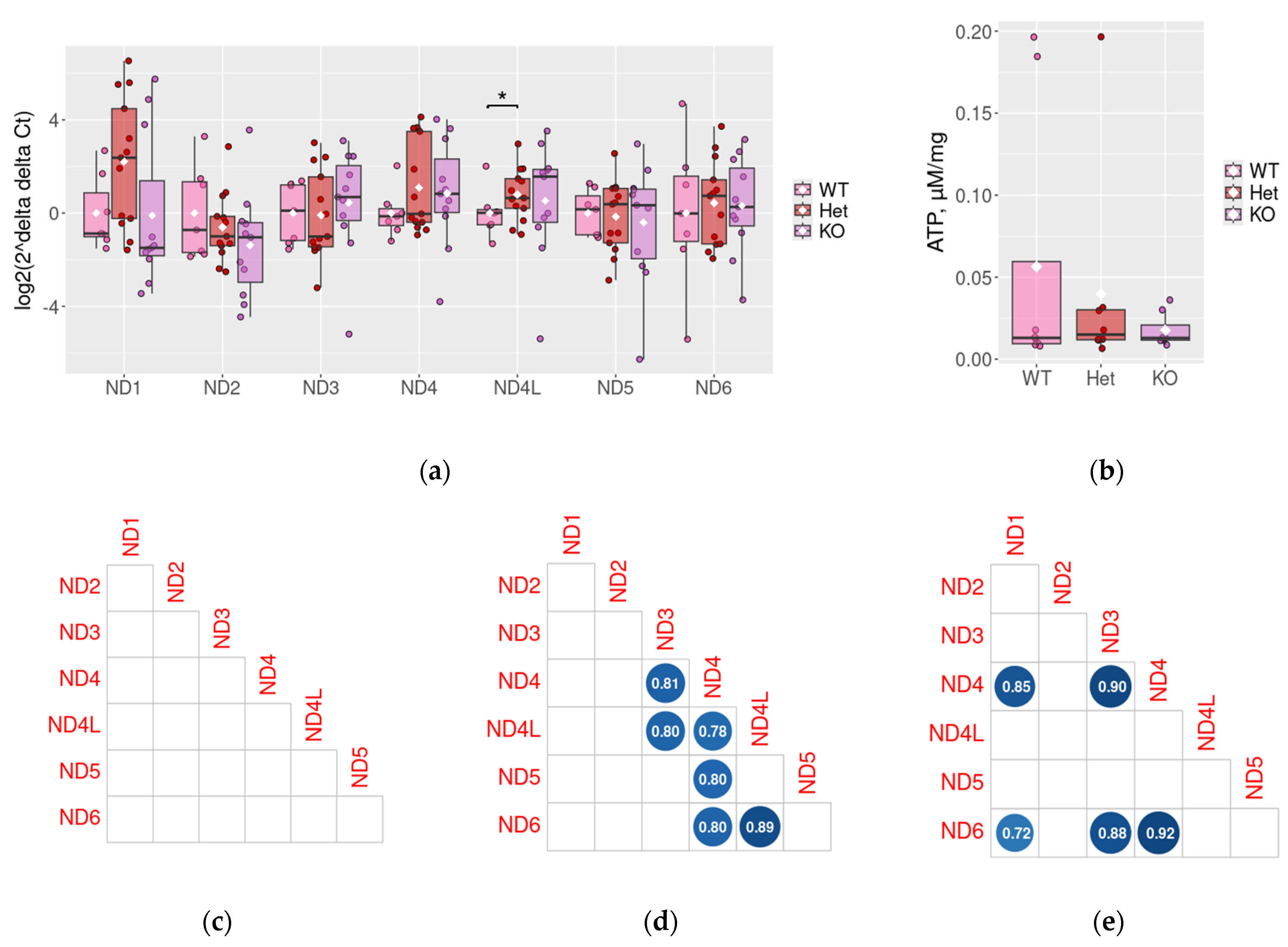

2.3. ND1–6 Expression in the Prefrontal Cortex in Rat DAT-KO ADHD Model

2.4. Measurement of ATP Levels in DAT-Het and DAT-KO Rats

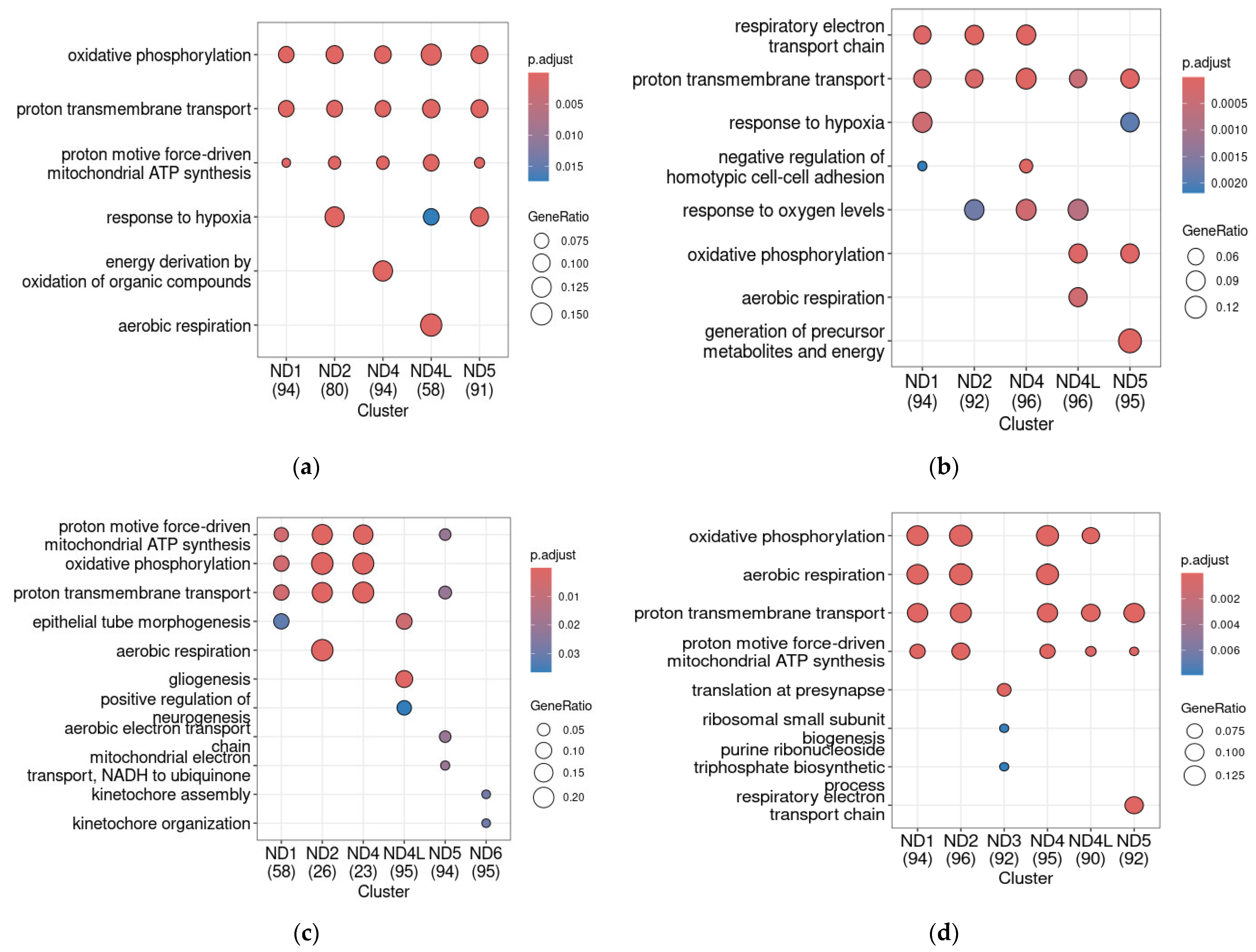

2.5. ND Genes Co-Expression Profiles in Mouse ADHD Models

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Gene Expression Omnibus Database Search

4.2. RNA-Seq Data Normalization and Statistical Analysis

4.3. Measurement of Co-Expression Profiles and Functional Analysis

4.4. Animals

4.5. RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

4.6. ATP Measurements

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Kafaji, G.; Jahrami, H.A.; Alwehaidah, M.S.; Alshammari, Y.; Husni, M. Mitochondrial DNA Copy Number in Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1196035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French, B.; Nalbant, G.; Wright, H.; Sayal, K.; Daley, D.; Groom, M.J.; Cassidy, S.; Hall, C.L. The Impacts Associated with Having ADHD: An Umbrella Review. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1343314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennum, P.; Sørensen, A.V.; Baandrup, L.; Ibsen, M.; Ibsen, R.; Kjellberg, J. Long-Term Effects of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) on Social Functioning and Health Care Outcomes. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 182, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öğütlü, H.; Kaşak, M.; Tabur, S.T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Eurasian J. Med. 2022, 54, S187–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, M.M.; Althekair, A.; Almutairi, F.; Alatabani, M.; Alsaikhan, A. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Mitophagy in ADHD: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Saudi Pharm. J. 2024, 32, 102212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandar, V.; Rajagopalan, K.; Jayaramayya, K.; Jeevanandam, M.; Iyer, M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Hidden Trigger of Autism? Genes Dis. 2021, 8, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttiker, P.; Weissenberger, S.; Esch, T.; Anders, M.; Raboch, J.; Ptacek, R.; Kream, R.M.; Stefano, G.B. Dysfunctional Mitochondrial Processes Contribute to Energy Perturbations in the Brain and Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 13, 1095923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Palomo, A.; Andreu, H.; de Juan, O.; Olivier, L.; Ochandiano, I.; Ilzarbe, L.; Valentí, M.; Stoppa, A.; Llach, C.-D.; Pacenza, G.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction as a Biomarker of Illness State in Bipolar Disorder: A Critical Review. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morella, I.M.; Brambilla, R.; Morè, L. Emerging Roles of Brain Metabolism in Cognitive Impairment and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 142, 104892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, K.; Roth, E.; Chao, D.; Mecca, C.M.; Hogan, Q.H.; Pawela, C.; Kwok, W.-M.; Camara, A.K.S.; Pan, B. Repetitive Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats Impairs Cognition, Enhances Prefrontal Cortex Neuronal Activity, and Reduces Pre-Synaptic Mitochondrial Function. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 689334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliulin, I.; Hamoudi, W.; Amal, H. The Multifaceted Role of Mitochondria in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, Y.; Okura, S.; Sukigara, A.; Matsunaga, A.; Maekubo, K.; Oue, T.; Ishihara, K.; Deguchi, Y.; Inoue, K. The Association Among Bipolar Disorder, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Reactive Oxygen Species. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Yang, F. The Interplay of Dopamine Metabolism Abnormalities and Mitochondrial Defects in the Pathogenesis of Schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, O.; Karry, R.; Milhem, J.; Ben-Shachar, D. NDUFV2 Pseudogene (NDUFV2P1) Contributes to Mitochondrial Complex I Deficits in Schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, G.; Mazza, B.; Vellucci, L.; Barone, A.; Ciccarelli, M.; de Bartolomeis, A. Schizophrenia Synaptic Pathology and Antipsychotic Treatment in the Framework of Oxidative and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Translational Highlights for the Clinics and Treatment. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marazziti, D.; Baroni, S.; Picchetti, M.; Landi, P.; Silvestri, S.; Vatteroni, E.; Dell’Osso, M.C. Mitochondrial Alterations and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 4715–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morén, C.; Olivares-Berjaga, D.; Martínez-Pinteño, A.; Bioque, M.; Rodríguez, N.; Gassó, P.; Martorell, L.; Parellada, E. Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation System Dysfunction in Schizophrenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.M.; Hagenauer, M.H.; Krolewski, D.M.; Hughes, E.; Forrester, L.C.T.; Walsh, D.M.; Waselus, M.; Richardson, E.; Turner, C.A.; Sequeira, P.A.; et al. Neurotransmission-Related Gene Expression in the Frontal Pole Is Altered in Subjects with Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holper, L.; Ben-Shachar, D.; Mann, J.J. Multivariate Meta-Analyses of Mitochondrial Complex I and IV in Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia, Alzheimer Disease, and Parkinson Disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.C.; Hjelm, B.E.; Rollins, B.L.; Sequeira, A.; Morgan, L.; Omidsalar, A.A.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Barchas, J.D.; Lee, F.S.; Myers, R.M.; et al. Mitochondria DNA Copy Number, Mitochondria DNA Total Somatic Deletions, Complex I Activity, Synapse Number, and Synaptic Mitochondria Number Are Altered in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.E.; Cleary, D.W.; Clarke, S.C. Secondary Bacterial Infections Associated with Influenza Pandemics. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.-J.; Lu, Y.-R.; Shi, L.-G.; Demmers, J.A.A.; Bezstarosti, K.; Rijkers, E.; Balesar, R.; Swaab, D.; Bao, A.-M. Distinct Proteomic Profiles in Prefrontal Subareas of Elderly Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder Patients. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Spekker, E.; Polyák, H.; Tóth, F.; Vécsei, L. Mitochondrial Impairment: A Common Motif in Neuropsychiatric Presentation? The Link to the Tryptophan–Kynurenine Metabolic System. Cells 2022, 11, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E.; Lionnard, L.; Singh, I.; Karim, M.A.; Chajra, H.; Frechet, M.; Kissa, K.; Racine, V.; Ammanamanchi, A.; McCarty, P.J.; et al. Mitochondrial Morphology Is Associated with Respiratory Chain Uncoupling in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damri, O.; Asslih, S.; Shemesh, N.; Natour, S.; Noori, O.; Daraushe, A.; Einat, H.; Kara, N.; Las, G.; Agam, G. Using Mitochondrial Respiration Inhibitors to Design a Novel Model of Bipolar Disorder-like Phenotype with Construct, Face and Predictive Validity. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, X.-J.; Xu, B.; Yeo, P.-L.; Cheah, P.-S.; Ling, K.-H. Mitochondria Dysfunction and Bipolar Disorder: From Pathology to Therapy. IBRO Neurosci. 2023, 14, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzl, E.J.; Srihari, V.H.; Mustapic, M.; Kapogiannis, D.; Heninger, G.R. Abnormal Levels of Mitochondrial Ca2+ Channel Proteins in Plasma Neuron-Derived Extracellular Vesicles of Early Schizophrenia. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, M.; Morris, C.M.; Heim, K.; Bender, A.; Mehta, D.; Jaros, E.; Klopstock, T.; Meitinger, T.; Turnbull, D.M.; Prokisch, H. Expression Analysis of Dopaminergic Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease and Aging Links Transcriptional Dysregulation of Energy Metabolism to Cell Death. Acta Neuropathol. 2011, 122, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kim, J.-M.; Donovan, D.M.; Becker, K.G.; Li, M.D. Significant Modulation of Mitochondrial Electron Transport System by Nicotine in Various Rat Brain Regions. Mitochondrion 2009, 9, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vaidya, B.; Gupta, P.; Biswas, S.; Laha, J.K.; Roy, I.; Sharma, S.S. Effect of Clemizole on Alpha-Synuclein-Preformed Fibrils-Induced Parkinson’s Disease Pathology: A Pharmacological Investigation. Neuromol. Med. 2024, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullaev, S.; Gubina, N.; Bulanova, T.; Gaziev, A. Assessment of Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA, Expression of Mitochondria-Related Genes in Different Brain Regions in Rats after Whole-Body X-Ray Irradiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.G.; Seligsohn, M.; Rubin, T.G.; Griffiths, B.B.; Ozdemir, Y.; Pfaff, D.W.; Datson, N.A.; McEwen, B.S. Stress and Corticosteroids Regulate Rat Hippocampal Mitochondrial DNA Gene Expression via the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9099–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.-C.; Wang, L.-J.; Kuo, H.-C.; Tsai, C.-S.; Chou, W.-J.; Li, C.-J.; Liu, A.-C.; Yeh, H.-Y.; Chen, D.-W.; Lee, S.-Y. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Study Reveals the Potential Role of the RPS26 Gene in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2025, 141, 111444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakulski, K.M.; Halladay, A.; Hu, V.W.; Mill, J.; Fallin, M.D. Epigenetic Research in Neuropsychiatric Disorders: The “Tissue Issue”. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Rep. 2016, 3, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Oh, C.-M.; Ohara-Imaizumi, M.; Park, S.; Namkung, J.; Yadav, V.K.; Tamarina, N.A.; Roe, M.W.; Philipson, L.H.; Karsenty, G.; et al. Functional Role of Serotonin in Insulin Secretion in a Diet-Induced Insulin-Resistant State. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ledoux, P.; Evangelista, C.; Kim, I.F.; Tomashevsky, M.; Marshall, K.A.; Phillippy, K.H.; Sherman, P.M.; Holko, M.; et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for Functional Genomics Data Sets—Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D991–D995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, D.; Sukhanov, I.; Zoratto, F.; Illiano, P.; Caffino, L.; Sanna, F.; Messa, G.; Emanuele, M.; Esposito, A.; Dorofeikova, M.; et al. Pronounced Hyperactivity, Cognitive Dysfunctions, and BDNF Dysregulation in Dopamine Transporter Knock-out Rats. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del’Guidice, T.; Lemasson, M.; Etiévant, A.; Manta, S.; Magno, L.A.V.; Escoffier, G.; Roman, F.S.; Beaulieu, J.-M. Dissociations between Cognitive and Motor Effects of Psychostimulants and Atomoxetine in Hyperactive DAT-KO Mice. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, A.; Targa, G.; Fesenko, Z.; Leo, D.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Sukhanov, I. Dopamine Transporter Deficient Rodents: Perspectives and Limitations for Neuroscience. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptukha, M.; Fesenko, Z.; Belskaya, A.; Gromova, A.; Pelevin, A.; Kurzina, N.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Volnova, A. Effects of Atomoxetine on Motor and Cognitive Behaviors and Brain Electrophysiological Activity of Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzina, N.; Belskaya, A.; Gromova, A.; Ignashchenkova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Volnova, A. Modulation of Spatial Memory Deficit and Hyperactivity in Dopamine Transporter Knockout Rats via α2A-Adrenoceptors. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 851296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giros, B.; Jaber, M.; Jones, S.R.; Wightman, R.M.; Caron, M.G. Hyperlocomotion and Indifference to Cocaine and Amphetamine in Mice Lacking the Dopamine Transporter. Nature 1996, 379, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sora, I.; Wichems, C.; Takahashi, N.; Li, X.F.; Zeng, Z.; Revay, R.; Lesch, K.P.; Murphy, D.L.; Uhl, G.R. Cocaine Reward Models: Conditioned Place Preference Can Be Established in Dopamine- and in Serotonin-Transporter Knockout Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 7699–7704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gainetdinov, R.R.; Jones, S.R.; Caron, M.G. Functional Hyperdopaminergia in Dopamine Transporter Knock-out Mice. Biol. Psychiatry 1999, 46, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, R.J.; Paulus, M.P.; Fumagalli, F.; Caron, M.G.; Geyer, M.A. Prepulse Inhibition Deficits and Perseverative Motor Patterns in Dopamine Transporter Knock-out Mice: Differential Effects of D1 and D2 Receptor Antagonists. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, J.V.; Nehrenberg, D.L.; Jacobsen, J.P.R.; Caron, M.G.; Wetsel, W.C. Differential Psychostimulant-Induced Activation of Neural Circuits in Dopamine Transporter Knockout and Wild Type Mice. Neuroscience 2003, 118, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Bruno, K.J.; Hess, E.J. Rodent Models of ADHD. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2012, 9, 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainetdinov, R.R.; Mohn, A.R.; Caron, M.G. Genetic Animal Models: Focus on Schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2001, 24, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M.A.; Panessiti, M.G.; Hall, F.S.; Uhl, G.R.; Murphy, D.L. An Evaluation of the Serotonin System and Perseverative, Compulsive, Stereotypical, and Hyperactive Behaviors in Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Knockout Mice. Psychopharmacology 2013, 227, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adinolfi, A.; Zelli, S.; Leo, D.; Carbone, C.; Mus, L.; Illiano, P.; Alleva, E.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Adriani, W. Behavioral Characterization of DAT-KO Rats and Evidence of Asocial-like Phenotypes in DAT-HET Rats: The Potential Involvement of Norepinephrine System. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 359, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoni, G.; Puzzo, C.; Gigantesco, A.; Adriani, W. Behavioral Phenotype in Heterozygous DAT Rats: Transgenerational Transmission of Maternal Impact and the Role of Genetic Asset. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainetdinov, A.R.; Fesenko, Z.S.; Khismatullina, Z.R. Behavioural Changes in Heterozygous Rats by Gene Knockout of the Dopamine Transporter (DAT). J. Biomed. 2020, 16, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miller, C.J.; Golovina, E.; Gokuladhas, S.; Wicker, J.S.; Jacobsen, J.C.; O’Sullivan, J.M. Unraveling ADHD: Genes, Co-Occurring Traits, and Developmental Dynamics. Life Sci. Alliance 2025, 8, e202403029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, C.M.; Ip, H.F.; Schipper, M.; Hottenga, J.-J.; St Pourcain, B.; Zayats, T.; Pool, R.; Krapohl, E.M.L.; Brikell, I.; Soler Artigas, M.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Meta-Analysis of Childhood ADHD Symptoms and Diagnosis Identifies New Loci and Potential Effector Genes. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 2427–2435, Correction in Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesch, K.-P.; Selch, S.; Renner, T.J.; Jacob, C.; Nguyen, T.T.; Hahn, T.; Romanos, M.; Walitza, S.; Shoichet, S.; Dempfle, A.; et al. Genome-Wide Copy Number Variation Analysis in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Association with Neuropeptide Y Gene Dosage in an Extended Pedigree. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, I.W.; Hong, J.H.; Kwon, B.N.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, N.R.; Lim, M.H.; Kwon, H.J.; Jin, H.J. Association of Mitochondrial DNA 10398 A/G Polymorphism with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder in Korean Children. Gene 2017, 630, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Shum, E.; Jones, S.; Lou, C.-H.; Chousal, J.; Kim, H.; Roberts, A.; Jolly, L.; Espinoza, J.; Skarbrevik, D.; et al. A Upf3b-Mutant Mouse Model with Behavioral and Neurogenesis Defects. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Martínez, J.; Saz-Navarro, D.M.; López-Fernández, A.; Rodríguez-Baena, D.S.; Gómez-Vela, F.A. Computational Ensemble Gene Co-Expression Networks for the Analysis of Cancer Biomarkers. Informatics 2024, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabbott, N.A.; Baillie, J.K.; Brown, H.; Freeman, T.C.; Hume, D.A. An Expression Atlas of Human Primary Cells: Inference of Gene Function from Coexpression Networks. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singh, A.; Nthenge-Ngumbau, D.N.; Rajamma, U.; Sinha, S.; Mukhopadhyay, K.; Mohanakumar, K.P. Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder Suffers from Mitochondrial Dysfunction. BBA Clin. 2016, 6, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Payares, D.V.; Spooner, L.; Vosters, J.; Dominguez, S.; Patrick, L.; Harris, A.; Kanungo, S. A Systematic Review on the Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction/Disorders in Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Psychiatric/Behavioral Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1389093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoulis, S.V.; Müller, D.; Kennedy, J.L.; Gonçalves, V. Systematic Review of Mitochondrial Genetic Variation in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 33, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jedynak-Slyvka, M.; Jabczynska, A.; Szczesny, R.J. Human Mitochondrial RNA Processing and Modifications: Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, B.R.; Pio-Abreu, J.L.; Figueiredo, A.; Misery, L. Pruritus, Allergy and Autoimmunity: Paving the Way for an Integrated Understanding of Psychodermatological Diseases? Front. Allergy 2021, 2, 688999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.K.; Lu, J.; Bai, Y. Mitochondrial Respiratory Complex I: Structure, Function and Implication in Human Diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Pragasam, S.J.; Venkatesan, V. Emerging Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic Syndrome: Lessons from Animal Models. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2019, 19, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisman, G.; Melillo, R. Front and Center: Maturational Dysregulation of Frontal Lobe Functional Neuroanatomic Connections in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Front. Neuroanat. 2022, 16, 936025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsten, A.F.T. The Emerging Neurobiology of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: The Key Role of the Prefrontal Association Cortex. J. Pediatr. 2009, 154, I-S43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, T.R.; Neph, S.; Dinger, M.E.; Crawford, J.; Smith, M.A.; Shearwood, A.-M.J.; Haugen, E.; Bracken, C.P.; Rackham, O.; Stamatoyannopoulos, J.A.; et al. The Human Mitochondrial Transcriptome. Cell 2011, 146, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Martin, M.V.; Watson, S.J.; Schatzberg, A.; Akil, H.; Myers, R.M.; Jones, E.G.; Bunney, W.E.; Vawter, M.P. Mitochondrial Involvement in Psychiatric Disorders. Ann. Med. 2008, 40, 281–295, Erratum in Ann. Med. 2011, 43, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelm, B.E.; Rollins, B.; Mamdani, F.; Lauterborn, J.C.; Kirov, G.; Lynch, G.; Gall, C.M.; Sequeira, A.; Vawter, M.P. Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction within the Complex Genetic Etiology of Schizophrenia. Mol. Neuropsychiatry 2015, 1, 201–219, Erratum in Mol. Neuropsychiatry 2016, 2, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dóra, F.; Renner, É.; Keller, D.; Palkovits, M.; Dobolyi, Á. Transcriptome Profiling of the Dorsomedial Prefrontal Cortex in Suicide Victims. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weger, M.; Alpern, D.; Cherix, A.; Ghosal, S.; Grosse, J.; Russeil, J.; Gruetter, R.; de Kloet, E.R.; Deplancke, B.; Sandi, C. Mitochondrial Gene Signature in the Prefrontal Cortex for Differential Susceptibility to Chronic Stress. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrell, H.; Montaña, E.; Abasolo, N.; Roig, B.; Gaviria, A.M.; Vilella, E.; Martorell, L. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in Brain Samples from Patients with Major Psychiatric Disorders: Gene Expression Profiles, mtDNA Content and Presence of the mtDNA Common Deletion. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2013, 162B, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Geng, R.; Kang, S.-G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. Dietary L-Proline Supplementation Ameliorates Autism-like Behaviors and Modulates Gut Microbiota in the Valproic Acid-Induced Mouse Model of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Food Sci. Hum. Wellnes 2024, 13, 2889–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, C.; Brandt, U.; Hunte, C.; Zickermann, V. Structure and Function of Mitochondrial Complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2016, 1857, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbian, Y.; Ovadia, O.; Dadon, S.; Mishmar, D. Gene Expression Patterns of Oxidative Phosphorylation Complex I Subunits Are Organized in Clusters. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.S.; McShane, E.; Churchman, L.S. The Multiple Levels of Mitonuclear Coregulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2018, 52, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lambo, M.E.; Ge, X.; Dearborn, J.T.; Liu, Y.; McCullough, K.B.; Swift, R.G.; Tabachnick, D.R.; Tian, L.; Noguchi, K.; et al. A MYT1L Syndrome Mouse Model Recapitulates Patient Phenotypes and Reveals Altered Brain Development Due to Disrupted Neuronal Maturation. Neuron 2021, 109, 3775–3792.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hyun, T.K.; Han, X.; Feng, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, J. Coexpression within Integrated Mitochondrial Pathways Reveals Different Networks in Normal and Chemically Treated Transcriptomes. Int. J. Genom. 2014, 2014, 452891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, N.; Ganster, T.; O’Leary, A.; Popp, S.; Freudenberg, F.; Reif, A.; Soler Artigas, M.; Ribasés, M.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Lesch, K.-P.; et al. Dissociation of Impulsivity and Aggression in Mice Deficient for the ADHD Risk Gene Adgrl3: Evidence for Dopamine Transporter Dysregulation. Neuropharmacology 2019, 156, 107557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belskaya, A.; Kurzina, N.; Savchenko, A.; Sukhanov, I.; Gromova, A.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Volnova, A. Rats Lacking the Dopamine Transporter Display Inflexibility in Innate and Learned Behavior. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Arellano, L.; González-García, N.; Salazar-García, M.; Corona, J.C. Antioxidants as a Potential Target against Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Yao, W.; Xue, Z. Exploring Causal Associations of Antioxidants from Supplements and Diet with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in European Populations: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1415793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, E.a.F.; Paglialunga, S.; Gerling, C.; Whitfield, J.; Mukai, K.; Chabowski, A.; Heigenhauser, G.J.F.; Spriet, L.L.; Holloway, G.P. Omega-3 Supplementation Alters Mitochondrial Membrane Composition and Respiration Kinetics in Human Skeletal Muscle. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 1341–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagni, A.J.; Prater, M.C.; Paton, C.M.; Cooper, J.A. Cognitive Function in Response to a Pecan-Enriched Meal: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Cross-over Study in Healthy Adults. Nutr. Neurosci. 2025, 28, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyens, B.; Felgueroso-Bueno, F.; Massat, I. Beneficial Effects of Pycnogenol® on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Review of Clinical Outcomes and Mechanistic Insights. Arch. Pediatr. 2024, 9, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.; Chavarria, D.; Borges, F.; Wojtczak, L.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Karkucinska-Wieckowska, A.; Oliveira, P.J. Dietary Polyphenols and Mitochondrial Function: Role in Health and Disease. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 26, 3376–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahi, N.A.; Najafabadi, M.F.; Pilarczyk, M.; Kouril, M.; Medvedovic, M. GREIN: An Interactive Web Platform for Re-Analyzing GEO RNA-Seq Data. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, I.; Moreno, P.; Manning, J.; Fuentes, A.M.-P.; George, N.; Fexova, S.; Fonseca, N.A.; Füllgrabe, A.; Green, M.; Huang, N.; et al. Expression Atlas Update: From Tissues to Single Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D77–D83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-24277-4. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, X.; Chen, L.; Wan, X. Interpretable Transfer Learning for Cancer Drug Resistance: Candidate Target Identification. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojšin, R.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Z. A Model-Agnostic Computational Method for Discovering Gene–Phenotype Relationships and Inferring Gene Networks via in Silico Gene Perturbation. medRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gene Ontology Consortium; Aleksander, S.A.; Balhoff, J.; Carbon, S.; Cherry, J.M.; Drabkin, H.J.; Ebert, D.; Feuermann, M.; Gaudet, P.; Harris, N.L.; et al. The Gene Ontology Knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics 2023, 224, iyad031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix, Version 0.95. 2017. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Heidbreder, R. ADHD Symptomatology Is Best Conceptualized as a Spectrum: A Dimensional versus Unitary Approach to Diagnosis. ADHD Atten. Deficit Hyperact. Disord. 2015, 7, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset ID | Title | Sequencing Platform | Samples Characteristics | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE173926 | A MYT1L Syndrome mouse model recapitulates patient phenotypes and reveals altered brain development due to disrupted neuronal maturation [RNA-Seq] | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | PFC, adult male and female samples, heterozygous MYT1L mutants (n = 6) or wild-type (n = 6) mice | Heterozygous MYT1L mutants are hyperactive across numerous tasks, including open field, social operant and PPI/startle, as well as altered sociality [41]. |

| GSE117357 | Differential Gene Expression in Adgrl3 KO Mice | Illumina NovaSeq 500 | PFC, adult samples, Adgrl3 KO (n = 10) or wild-type (n = 10) mice | Adgrl3-deficient mice demonstrate increased locomotive activity, impulsivity, decreased visuospatial and recognition memory, and sociability [42]. |

| Gene | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| ND1 | CAA CTA CGC AAA GGC CCC AAC A | GGG AGA GGG TTG GGG CGA TAA T |

| ND2 | GGA CTA GCC CCC TTC CAC TA | GGC GCC AAC AAA GAC TGA TG |

| ND3 | CCC AAC AAG TTC TGC ACG CCT T | TTG AAT CGC TCA TGG GAG GGG G |

| ND4 | CCC ACG GCT TAA CCT CCT CAC T | GGG TGG TAG TGC TAG GTT GGC T |

| ND4L | ACT CTC CTC TGC CTA GAA GGA A | AAA CCT ACT GCT GCT TCG CA |

| ND5 | CGG CCC TCC AAG CAA TCC TCT A | GGA TGA AGT CCG AAT TGG GCG G |

| ND6 | ACT GGT TGT CTA GGG TTG GCG T | CCC TCA AGT CTC CGG GTA CTC C |

| Gapdh | CGC CTG GAG AAA CCT GCC AAG | CTG GTC CTC AGT GTA GCC CAG G |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sylko, P.A.; Gromova, A.A.; Fesenko, Z.S.; Kanov, E.V.; Volnova, A.B.; Gainetdinov, R.R.; Vaganova, A.N. Altered Co-Expression Patterns of Mitochondrial NADH-Dehydrogenase Genes in the Prefrontal Cortex of Rodent ADHD Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211079

Sylko PA, Gromova AA, Fesenko ZS, Kanov EV, Volnova AB, Gainetdinov RR, Vaganova AN. Altered Co-Expression Patterns of Mitochondrial NADH-Dehydrogenase Genes in the Prefrontal Cortex of Rodent ADHD Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211079

Chicago/Turabian StyleSylko, Polina A., Arina A. Gromova, Zoia S. Fesenko, Evgeny V. Kanov, Anna B. Volnova, Raul R. Gainetdinov, and Anastasia N. Vaganova. 2025. "Altered Co-Expression Patterns of Mitochondrial NADH-Dehydrogenase Genes in the Prefrontal Cortex of Rodent ADHD Models" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211079

APA StyleSylko, P. A., Gromova, A. A., Fesenko, Z. S., Kanov, E. V., Volnova, A. B., Gainetdinov, R. R., & Vaganova, A. N. (2025). Altered Co-Expression Patterns of Mitochondrial NADH-Dehydrogenase Genes in the Prefrontal Cortex of Rodent ADHD Models. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11079. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211079