The Role of Cytokines in the Development and Functioning of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axis in Mammals in Normal and Pathological Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

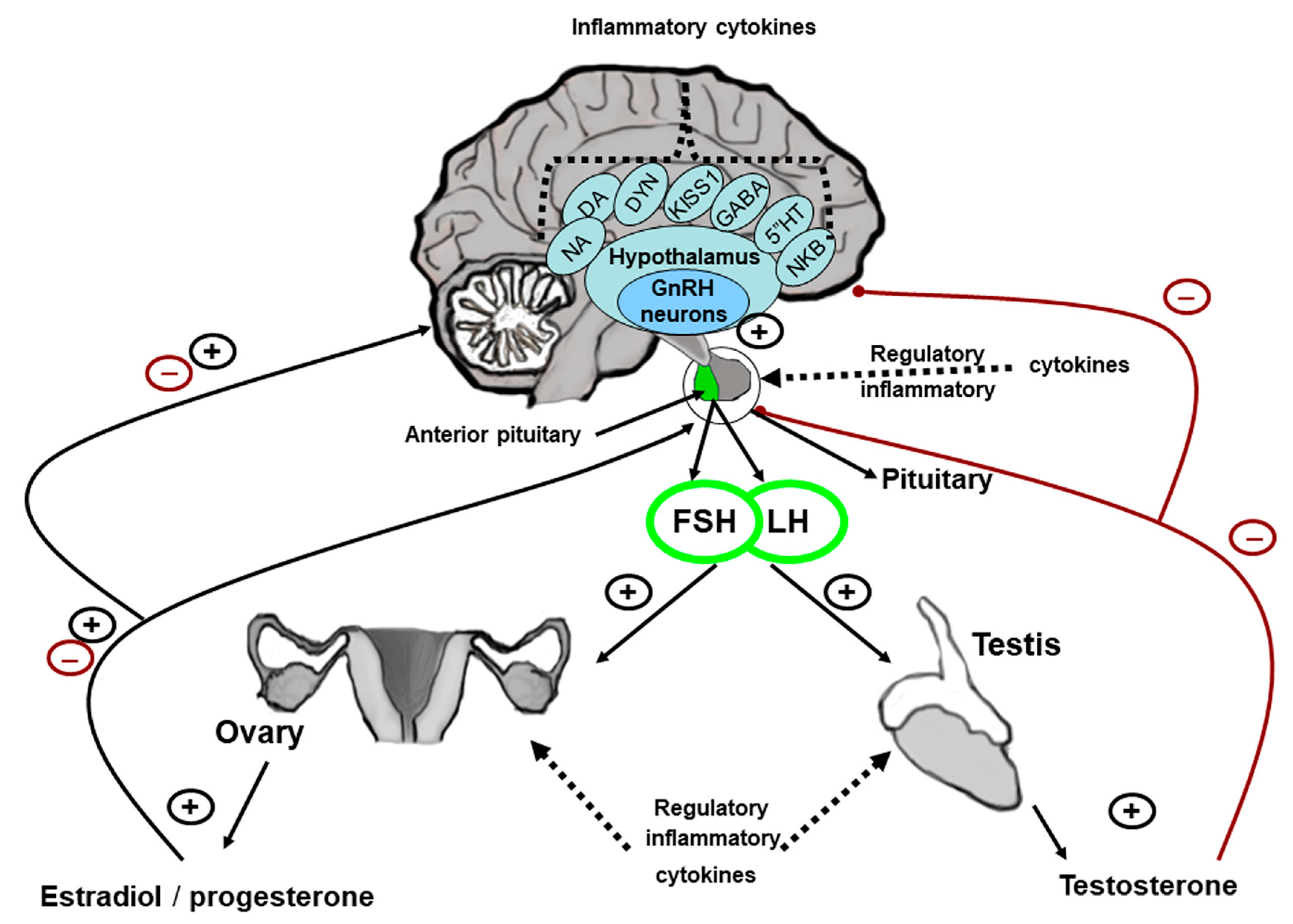

2. The Effect of Cytokines on the Functional Activity of the GnRH-Producing System in Sexually Mature Mammals

3. The Effect of Cytokines on the Functional Activity of the Anterior Pituitary

4. The Effect of Cytokines on the Functional Activity of the Gonads in Sexually Mature Males

5. The Effect of Cytokines on the Functional Activity of the Ovaries in Sexually Mature Females

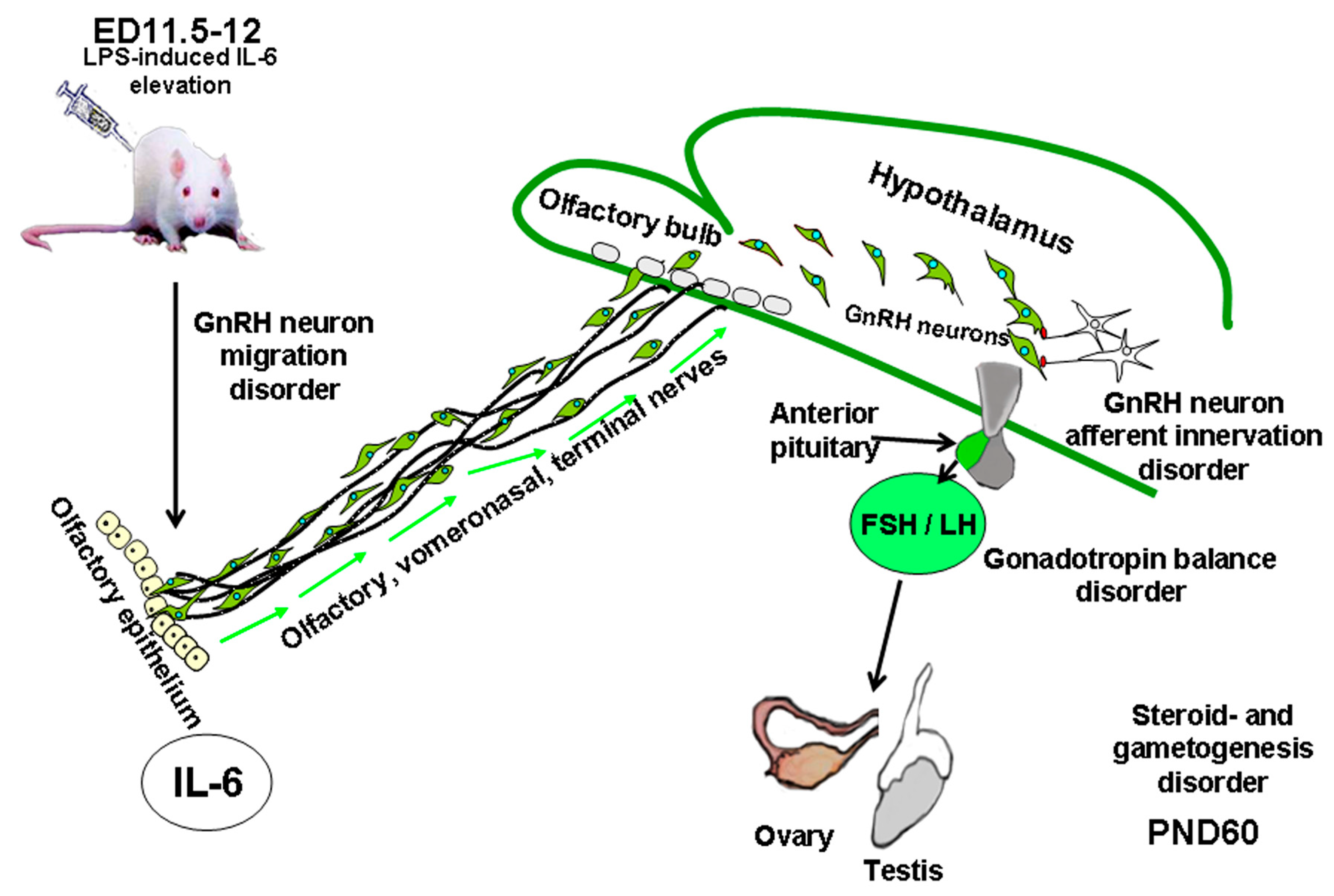

6. The Effect of Cytokines on the Developing Fetus

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNS | Central nervous system. |

| ED | Embryonic day. |

| ER | Estrogen receptor. |

| FSH | Follicle-stimulating hormone. |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid. |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor. |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone. |

| HGF/SF | Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor. |

| HPG | Hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (system). |

| IFNγ | Interferon gamma. |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G. |

| IL | Interleukin. |

| KISS | Kisspeptin. |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone. |

| LIF | Leukemia inhibitory factor. |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide. |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. |

| NFkB | Nuclear Factor kappa B. |

| SDF-1 | Stromal cell-derived factor 1 and one of its receptors CXCR4. |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor beta. |

| TLR | Toll-like receptors. |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor. |

References

- Simbirtsev, A. ImmunoPharmacological aspects of the cytokine system. Bull. Sib. Med. 2019, 18, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicherska-Pawłowska, K.; Wróbel, T.; Rybka, J. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs), NOD-Like Receptors (NLRs), and RIG-I-Like Receptors (RLRs) in Innate Immunity. TLRs, NLRs, and RLRs Ligands as Immunotherapeutic Agents for Hematopoietic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ge, P.; Zhu, Y. TLR2 and TLR4 in the brain injury caused by cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 124614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Kawai, T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, M.; Myhre, A.; Aasen, A.; Wang, J. Effects of forskolin on Kupffer cell production of interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor alpha differ from those of endogenous adenylyl cyclase activators: Possible role for adenylyl cyclase 9. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 7290–7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Wu, Q.; Mak, S.; Liu, E.; Zheng, B.; Dong, T.; Pi, R.; Tsim, K. Regulation of acetylcholinesterase during the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in microglial cells. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, C. Overview of the IL-1 family in innate inflammation and acquired immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 281, 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorrington, M.; Fraser, I. NF-κB Signaling in Macrophages: Dynamics, Crosstalk, and Signal Integration. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, S.; Chin, P.; Femia, J.; Brown, H. Embryotoxic cytokines-Potential roles in embryo loss and fetal programming. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018, 125, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardalan, M.; Chumak, T.; Vexler, Z.; Mallard, C. Sex-Dependent Effects of Perinatal Inflammation on the Brain: Implication for Neuro-Psychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izvolskaia, M.; Sharova, V.; Zakharova, L. Perinatal Inflammation Reprograms Neuroendocrine, Immune, and Reproductive Functions: Profile of Cytokine Biomarkers. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharova, V.; Ignatiuk, V.; Izvolskaia, M.; Zakharova, L. Disruption of Intranasal GnRH Neuronal Migration Route into the Brain Induced by Proinflammatory Cytokine IL-6: Ex Vivo and In Vivo Rodent Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiuk, V.; Izvolskaia, M.; Sharova, V.; Zakharova, L. Disruptions in Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Development and Their IgG Modulation after Prenatal Systemic Inflammation in Male Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbison, A. The Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Pulse Generator. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3723–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.; Herbison, A.; Lehman, M.; Navarro, V. Neuroendocrine control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone: Pulsatile and surge modes of secretion. J. Neuroendocr. 2022, 34, e13094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Chaudhry, N. Beyond GnRH, LH and FSH: The role of kisspeptin on hypothalalmic-pituitary gonadal (HPG) axis pathology and diagnostic consideration. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2021, 71, 1862–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Coolen, L.; Porter, D.; Goodman, R.; Lehman, M. KNDy Cells Revisited. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3219–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foradori, C.D.; Whitlock, B.K.; Daniel, J.A.; Zimmerman, A.D.; Jones, M.A.; Read, C.C.; Steele, B.P.; Smith, J.T.; Clarke, I.J.; Elsasser, T.H.; et al. Kisspeptin Stimulates GrowthHormone Release by Utilizing Neuropeptide Y Pathways and Is Dependent on the Presence of Ghrelin in the Ewe. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 3526–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattern, A.; Zellmann, T.; Beck-Sickinger, A. Processing, signaling, and physiological function of chemerin. IUBMB Life 2014, 66, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estienne, A.; Bongrani, A.; Reverchon, M.; Ramé, C.; Ducluzeau, P.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Involvement of Novel Adipokines, Chemerin, Visfatin, Resistin and Apelin in Reproductive Functions in Normal and Pathological Conditions in Humans and Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, G.; Odle, A.; MacNicol, M.; MacNicol, A. Th e Importance of Leptin to Reproduction. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqaa204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genchi, V.; Rossi, E.; Lauriola, C.; D’Oria, R.; Palma, G.; Borrelli, A.; Caccioppoli, C.; Giorgino, F.; Cignarelli, A. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction and Obesity-Related Male Hypogonadism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wolfe, A. Signaling of cytokines is important in regulation of GnRH neurons. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 45, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, K.; Kreisman, M.; McCosh, R.; Raad, A.; Breen, K. Peripheral interleukin-1β inhibits arcuate kiss1 cells and LH pulses in female mice. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 246, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirivelu, M.; Burnett, R.; Shin, A.; Kim, C.; MohanKumar, P.; MohanKumar, S. Interaction between GABA and norepinephrine in interleukin-1beta-induced suppression of the luteinizing hormone surge. Brain Res. 2009, 1248, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Yu, C.; Hsuchou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kastin, A. Neuroinflammation facilitates LIF entry into brain: Role of TNF. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008, 294, 1436–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabás, K.; Szabó-Meleg, E.; Ábrahám, I. Effect of inflammation on female gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons: Mechanisms and consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.; Skipor, J.; Krawczyńska, A.; Bochenek, J.; Wojtulewicz, K.; Pawlina, B.; Antushevich, H.; Herman, A.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D. Effect of Central Injection of Neostigmine on the Bacterial Endotoxin Induced Suppression of GnRH/LH Secretion in Ewes during the Follicular Phase of the Estrous Cycle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergani, C.; Routly, J.; Jones, D.; Pickavance, L.; Smith, R.; Dobson, H. KNDy neurone activation prior to the LH surge of the ewe is disrupted by LPS. Reproduction 2017, 154, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanobe, H.; Hayakawa, Y. Hypothalamic interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not interleukin-6, mediate the endotoxin-induced suppression of the reproductive axis in rats. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 4868–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleder, C.; Arias, P.; Refojo, D.; Nacht, S.; Moguilevsky, J. Interleukin-1 inhibits NMDA-stimulated GnRH secretion: Associated effects on the release of hypothalamic inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitters. Neuroimmunomodulation 2000, 7, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomczyk, M.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D.; Bochenek, J.; Herman, A.; Herman, A.P. Anandamide Influences Interleukin-1β Synthesis and IL-1 System Gene Expressions in the Ovine Hypothalamus during Endo-Toxin-Induced Inflammation. Animals 2021, 11, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.; Leonhardt, S.; Jarry, H.; Wuttke, W.; Kim, K. Effect of interleukin-1beta on gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) and GnRH receptor gene expression in castrated male rats. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2000, 12, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarchielli, E.; Comeglio, P.; Squecco, R.; Ballerini, L.; Mello, T.; Guarnieri, G.; Idrizaj, E.; Mazzanti, B.; Vignozzi, L.; Gallina, P.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Impairs Kisspeptin Signaling in Human Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Primary Neurons. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 102, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Fang, T.; Yang, X.; Luo, X.; Guo, A.; Newell, K.; Huang, X.; Yu, Y. Galantamine improves cognition, hippocampal inflammation, and synaptic plasticity impairments induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Hiney, J.; Dees, W. Actions and interactions of alcohol and transforming growth factor β1 on prepubertal hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2014, 38, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiney, J.; Srivastava, V.; Vaden Anderson, D.; Hartzoge, N.; Dees, W. Regulation of Kisspeptin Synthesis and Release in the Preoptic/Anterior Hypothalamic Region of Prepubertal Female Rats: Actions of IGF-1 and Alcohol. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 42, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litteljohn, D.; Rudyk, C.; Razmjou, S.; Dwyer, Z.; Syed, S.; Hayley, S. Individual and interactive sex-specific effects of acute restraint and systemic IFN-γ treatment on neurochemistry. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 102, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeur, M.; Refojo, D.; Wölfel, B.; Stalla, J.; Vargas, V.; Theodoropoulou, M.; Buchfelder, M.; Paez-Pereda, M.; Arzt, E.; Stalla, G. Interferon-gamma inhibits cellular proliferation and ACTH production in corticotroph tumor cells through a novel janus kinases-signal transducer and activator of transcription 1/nuclear factor-kappa B inhibitory signaling pathway. J. Endocrinol. 2008, 199, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Moreno, L.; Román, I.D.; Bajo, A.M. GHRH and the prostate. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2024, 26, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haedo, M.; Gerez, J.; Fuertes, M.; Giacomini, D.; Páez-Pereda, M.; Labeur, M.; Renner, U.; Stalla, G.; Arzt, E. Regulation of pituitary function by cytokines. Horm. Res. 2009, 72, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, V.A.; Mercer, E.M.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Arrieta, M.C. Evolutionary Significance of the Neuroendocrine Stress Axis on Vertebrate Immunity and the Influence of the Microbiome on Early-Life Stress Regulation and Health Outcomes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangelo, B.; Farrimond, D.; Pompilius, M.; Bowman, K. Interleukin-1 beta and thymic peptide regulation of pituitary and glial cell cytokine expression and cellular proliferation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 917, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilezikjian, L.; Turnbull, A.; Corrigan, A.; Blount, A.; Rivier, C.; Vale, W. Interleukin-1beta regulates pituitary follistatin and inhibin/activin betaB mRNA levels and attenuates FSH secretion in response to activin-A. Endocrinology 1998, 139, 3361–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tumurgan, Z.; Kanasaki, H.; Tumurbaatar, T.; Oride, A.; Okada, H.; Kyo, S. Roles of intracerebral activin, inhibin, and follistatin in the regulation of Kiss-1 gene expression: Studies using primary cultures of fetal rat neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2020, 23, 100785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumurbaatar, T.; Kanasaki, H.; Cairang, Z.; Lkhagvajav, B.; Oride, A.; Okada, H.; Kyo, S. Potential role of kisspeptin in the estradiol-induced modulation of inhibin subunit gene expression: Insights from in vivo rat models and hypothalamic cell models. Endocr. J. 2025, 72, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, A.; Giacomini, D.; Castro, C.; Pereda, M.; Renner, U.; Stalla, G.; Arzt, E. Transcriptional regulation of interleukin-6 in pituitary folliculo-stellate TtT/GF cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 201, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vennekens, A.; Laporte, E.; Hermans, F.; Cox, B.; Modave, E.; Janiszewski, A.; Nys, C.; Kobayashi, H.; Malengier-Devlies, B.; Chappell, J.; et al. Interleukin-6 is an activator of pituitary stem cells upon local damage, a competence quenched in the aging gland. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2100052118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapochnik, M.; Haedo, M.; Fuertes, M.; Ajler, P.; Carrizo, G.; Cervio, A.; Sevlever, G.; Stalla, G.; Arzt, E. Autocrine IL-6 mediates pituitary tumor senescence. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 4690–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laporte, E.; De Vriendt, S.; Hoekx, J.; Vankelecom, H. Interleukin-6 is dispensable in pituitary normal development and homeostasis but needed for pituitary stem cell activation following local injury. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 1092063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, T.; Patel, R.; Stead, C.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R.; Buckingham, J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor is released from pituitary folliculo-stellate-like cells by endotoxin and dexamethasone and attenuates the steroid-induced inhibition of interleukin 6 release. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Calandra, T.; Bucala, R. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (MIF): A Glucocorticoid Counter-Regulator within the Immune System. Crit. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 37, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M.; Pearce, B.; Biron, C.; Miller, A. Immune modulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during viral infection. Viral Immunol. 2005, 18, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denef, C. Paracrinicity: The story of 30 years of cellular pituitary crosstalk. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, S.; McCann, S. Anterior pituitary hormone control by interleukin 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 2961–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelfsema, F.; Liu, P.; Yang, R.; Takahashi, P.; Veldhuis, J. Interleukin-2 drives cortisol secretion in an age-, dose-, and body composition-dependent way. Endocr. Connect. 2020, 9, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timaxian, C.; Raymond-Letron, I.; Bouclier, C.; Gulliver, L.; Le Corre, L.; Chebli, K.; Guillou, A.; Mollard, P.; Balabanian, K.; Lazennec, G. The health status alters the pituitary function and reproduction of mice in a Cxcr2-dependent manner. Life Sci. Alliance 2020, 3, e201900599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, T.; Lodge, E.; Andoniadou, C.; Yianni, V. Cellular interactions in the pituitary stem cell niche. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtulewicz, K.; Krawczyńska, A.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D.; Wójcik, M.; Herman, A. Effect of Acute and Prolonged Inflammation on the Gene Expression of Proinflammatory Cytokines and Their Receptors in the Anterior Pituitary Gland of Ewes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haziak, K.; Herman, A.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D. Effects of central injection of anti-LPS antibody and blockade of TLR4 on GnRH/LH secretion during immunological stress in anestrous ewes. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 2014, 867170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.; Skipor, J.; Krawczyńska, A.; Bochenek, J.; Wojtulewicz, K.; Antushevich, H.; Herman, A.; Paczesna, K.; Romanowicz, K.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D. Peripheral Inhibitor of AChE, Neostigmine, Prevents the Inflammatory Dependent Suppression of GnRH/LH Secretion during the Follicular Phase of the Estrous Cycle. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6823209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Wang, T.; Han, D. Structural, cellular and molecular aspects of immune privilege in the testis. Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Li, S.; Matsuyama, S.; DeFalco, T. Immune Cells as Critical Regulators of Steroidogenesis in the Testis and Beyond. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 894437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossadegh-Keller, N.; Gentek, R.; Gimenez, G.; Bigot, S.; Mailfert, S.; Sieweke, M. Developmental origin and maintenance of distinct testicular macrophage populations. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2829–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFalco, T.; Potter, S.; Williams, A.; Waller, B.; Kan, M.; Capel, B. Macrophages Contribute to the Spermatogonial Niche in the Adult Testis. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 1107–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, A.; DeFalco, T. Essential roles of interstitial cells in testicular development and function. Andrology 2020, 8, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytan, F.; Bellido, C.; Aguilar, E.; van Rooijen, N. Requirement for Testicular Macrophages in Leydig Cell Proliferation and Differentiation During Prepubertal Development in Rats. J. Reprod. Fertil. 1994, 102, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, S.; Cerri, P.; Sasso-Cerri, E. Impaired macrophages and failure of steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis in rat testes with cytokines deficiency induced by diacerein. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 156, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maegawa, M.; Kamada, M.; Irahara, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Yoshikawa, S.; Kasai, Y.; Ohmoto, Y.; Gima, H.; Thaler, C.J.; Aono, T. A repertoire of cytokines in human seminal plasma. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2002, 54, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shechter, R.; London, A.; Kuperman, Y.; Ronen, A.; Rolls, A.; Chen, A.; Schwartz, M. Hypothalamic neuronal toll-like receptor 2 protects against age-induced obesity. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leisegang, K.; Henkel, R. The in vitro modulation of steroidogenesis by inflammatory cytokines and insulin in TM3 Leydig cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svechnikov, K.; Sultana, T.; Soder, O. Age-Dependent Stimulation of Leydig Cell Steroidogenesis by Interleukin-1 Isoforms. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2001, 182, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerendai, I.; Banczerowski, P.; Csernus, V. Interleukin 1-beta injected into the testis acutely stimulates and later attenuates testicular steroidogenesis of the immature rat. Endocrine 2005, 28, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedger, M.; Klug, J.; Fröhlich, S.; Müller, R.; Meinhardt, A. Regulatory cytokine expression and interstitial fluid formation in the normal and inflamed rat testis are under leydig cell control. J. Androl. 2005, 26, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Kang, Y.; Wahl, E.; Park, H.; Lazova, R.; Leng, L.; Mamula, M.; Krishnaswamy, S.; Bucala, R.; Kang, I. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Regulates U1 Small Nuclear RNP Immune Complex-Mediated Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019, 71, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Gong, E.; Hong, C.; Park, E.; Ahn, R.; Park, K.; Lee, K. Reduced testicular steroidogenesis in tumor necrosis factor-alpha knockout mice. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 112, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suominen, J.; Wang, Y.; Kaipia, A.; Toppari, J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) promotes cell survival during spermatogenesis, and this effect can be blocked by infliximab, a TNF-α antagonist. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 151, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfino, F.; Boustead, J.; Fix, C.; Walker, W. NF-κB and TNF-α stimulate androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003, 201, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Park, J.; Seo, K.; Kim, J.; Im, S.; Lee, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, K. Expression of MIS in the testis is downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha through the negative regulation of SF-1 transactivation by NF-kappa B. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 6000–6012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentikäinen, V.; Pentikäinen, P.; Erkkilä, K.; Erkkilä, E.; Suomalainen, L.; Otala, M.; Pentikäinen, M.; Parvinen, M.; Dunkel, L. TNF down-regulates the Fas Ligand and inhibits germ cell apoptosis in the human testis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 4480–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves-Silva, T.; Freitas, G.; Húngaro, T.; Arruda, A.; Oyama, L.; Avellar, M.; Araujo, R. Interleukin-6 deficiency modulates testicular function by increasing the expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Singh, S.; Sharma, P.; Saini, R. Acute effect of moderate-intensity concentric and eccentric exercise on cardiac effort, perceived exertion and interleukin-6 level in physically inactive males. J. Sports. Med. Phys. Fit. 2019, 59, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedger, M.; Meinhardt, A. Cytokines and the immune-testicular axis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2003, 58, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, K.; Klein, B.; Pueschl, D.; Indumathy, S.; Bergmann, M.; Loveland, B.; Hedger, M.; Schuppe, H. Cytokines in male fertility and reproductive pathologies: Immunoregulation and beyond. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Sun, F. Interleukin-6 disrupts blood-testis barrier through inhibiting protein degradation or activating phosphorylated ERK in Sertoli cells. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, K.; Harakal, J.; Qiao, H.; Rival, C.; Li, J.; Paul, A.; Wheeler, K.; Pramoonjago, P.; Grafer, C.; Sun, W.; et al. Egress of sperm autoantigen from seminiferous tubules maintains systemic tolerance. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, S.; Theas, M.S.; Guazzone, V.A.; Jacobo, P.; Wang, M.; Fijak, M.; Meinhardt, A.; Lustig, L. Immune Cell Subtypes and Their Function in the Testis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Bryan, M.; Gerdprasert, O.; Nikolic-Paterson, D.; Meinhardt, A.; Muir, J.; Foulds, L.; Phillips, D.; de Kretser, D.; Hedger, M. Cytokine profiles in the testes of rats treated with lipopolysaccharide reveal localized suppression of inflammatory responses. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 288, R1744–R1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedger, M.P.; Winnall, W.R. Regulation of activin and inhibin in the adult testis and the evidence for functional roles in spermatogenesis and immunoregulation. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2012, 359, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, A.; McFarlane, J.; Seitz, J.; de Kretser, D. Activin maintains the condensed type of mitochondria in germ cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2000, 168, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousa, S.; Semitekolou, M.; Morianos, I.; Banos, A.; Trochoutsou, A.; Brodie, T.; Poulos, N.; Samitas, K.; Kapasa, M.; Konstantopoulos, D.; et al. Activin-A co-opts IRF4 and AhR signaling to induce human regulatory T cells that restrain asthmatic responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E2891–E2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremellen, K.; McPhee, N.; Pearce, K.; Benson, S.; Schedlowski, M.; Engler, H. Endotoxin-initiated inflammation reduces testosterone production in men of reproductive age. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 314, E206–E213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, F.; De Santi, F.; Vendramini, V.; Cabral, R.; Miraglia, S.; Cerri, P.; Sasso-Cerri, E. Vitamin B12 prevents cimetidine-induced androgenic failure and damage to sperm quality in rats. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garolla, A.; Pizzol, D.; Bertoldo, A.; Menegazzo, M.; Barzon, L.; Foresta, C. Sperm viral infection and male infertility: Focus on HBV, HCV, HIV, HPV, HSV, HCMV, and AAV. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2013, 100, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, C.; Adam, M.; Glashauser, L.; Dietrich, K.; Schwarzer, J.; Köhn, F.; Strauss, L.; Welter, H.; Poutanen, M.; Mayerhofer, A. Sterile inflammation as a factor in human male infertility: Involvement of Toll like receptor 2, biglycan and peritubular cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walenta, L.; Fleck, D.; Fröhlich, T.; von Eysmondt, H.; Arnold, G.; Spehr, J.; Schwarzer, J.; Köhn, F.; Spehr, M.; Mayerhofer, A. ATP-mediated Events in Peritubular Cells Contribute to Sterile Testicular Inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Østergren, P.; Dupree, J.; Ohl, D.; Sønksen, J.; Fode, M. Varicocele and male infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2017, 14, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, T.; Deng, T.; Xiong, W.; Lui, P.; Li, N.; Chen, Y.; Han, D. Damaged spermatogenic cells induce inflammatory gene expression in mouse Sertoli cells through the activation of Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 365, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert-Kruse, W.; Kiefer, I.; Beck, C.; Demirakca, T.; Strowitzki, T. Role for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and interleukin 1-beta (IL-1beta) determination in seminal plasma during infertility investigation. Fertil. Steril. 2007, 87, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, N.; Bahmani, M.; Kheradmand, A.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. The Impact of Oxidative Stress on Testicular Function and the Role of Antioxidants in Improving it: A Review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, IE01–IE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghimi, N.; Eslami Farsani, B.; Ghadipasha, M.; Mahmoudiasl, G.R.; Piryaei, A.; Aliaghaei, A.; Abdi, S.; Abbaszadeh, H.A.; Abdollahifar, M.A.; Forozesh, M. COVID-19 disrupts spermatogenesis through the oxidative stress pathway following induction of apoptosis. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Kepsch, A.; Kracht, T.O.; Hasan, H.; Wijayarathna, R.; Wahle, E.; Pleuger, C.; Bhushan, S.; Günther, S.; Kauerhof, A.C.; et al. Activin A and CCR2 regulate macrophage function in testicular fibrosis caused by experimental autoimmune orchitis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, S.R.; Rutkowski, H.; Vrezas, I. Cytokines and steroidogenesis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004, 215, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, S.; Dang, Y.; Zanvit, P.; Jin, W.; Chen, Z.J.; Chen, W.; et al. Treg deficiency-mediated TH 1 response causes human premature ovarian insufficiency through apoptosis and steroidogenesis dysfunction of granulosa cells. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M.; Sartorius, G.; Christ-Crain, M. Chronic low-grade inflammation in polycystic ovary syndrome: Is there a (patho)-physiological role for interleukin-1? Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.; Zhu, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Li, X.; Qi, J.; Wu, H.; Sun, Y. IL-1β Upregulates StAR and Progesterone Production Through the ERK1/2- and p38-Mediated CREB Signaling Pathways in Human Granulosa-Lutein Cells. Endocrinology 2017, 158, 3281–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlock, C.I.; Wu, J.; Zhou, C.; Tatum, K.; Adams, H.P.; Tan, F.; Lou, Y. Unique temporal and spatial expression patterns of IL-33 in ovaries during ovulation and estrous cycle are associated with ovarian tissue homeostasis. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Carlock, C.; Zhou, C.; Nakae, S.; Hicks, J.; Adams, H.P.; Lou, Y. IL-33 is required for disposal of unnecessary cells during ovarian atresia through regulation of autophagy and macrophage migration. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 2140–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, Z.; Fang, F.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Si, P.; Bian, Y.; Qin, Y.; et al. Two distinct resident macrophage populations coexist in the ovary. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1007711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.G.; Huang, L.; VanderVen, B.C. Immunometabolism at the interface between macrophages and pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Peng, X.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Yang, W.; Dou, X.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles regulate follicular activation and improve ovarian function in old mice by modulating local environment. Clin. Transl. Med. 2022, 12, e1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnik, K.; Tadmor, A.; Ben-Dor, S.; Nevo, N.; Galiani, D.; Dekel, N. Reactive oxygen species are indispensable in ovulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1462–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Chang, H.M.; Xie, J.; Wang, J.H.; Yang, J.; Leung, P.C.K. The interleukin 6 trans-signaling increases prostaglandin E2 production in human granulosa cells. Biol. Reprod. 2021, 105, 1189–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Kim, B.; Koo, D.B.; Lee, D.S. Peroxiredoxin 1 Controls Ovulation and Ovulated Cumulus-Oocyte Complex Activity through TLR4-Derived ERK1/2 Signaling in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niringiyumukiza, J.D.; Cai, H.; Xiang, W. Prostaglandin E2 involvement in mammalian female fertility: Ovulation, fertilization, embryo development and early implantation. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamba, S.; Yodoi, R.; Segi-Nishida, E.; Ichikawa, A.; Narumiya, S.; Sugimoto, Y. Timely interaction between prostaglandin and chemokine signaling is a prerequisite for successful fertilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 14539–14544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo, J.L.; Jaworski, J.P.; Peluffo, M.C. Direct role of the C-C motif chemokine receptor 2/monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 system in the feline cumulus oocyte complex. Biol. Reprod. 2019, 100, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Chang, H.M.; Cheng, J.C.; Leung, P.C.; Sun, Y.P. TGF-β1 downregulates StAR expression and decreases progesterone production through Smad3 and ERK1/2 signaling pathways in human granulosa cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, E2234–E2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chang, H.M.; Shi, Z.; Leung, P.C.K. ID3 mediates the TGF-β1-induced suppression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in human granulosa cells. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 4310–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chang, H.M.; Cheng, J.C.; Tsai, H.D.; Wu, C.H.; Leung, P.C. Transforming growth factor-β1 up-regulates connexin43 expression in human granulosa cells. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 2190–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Chang, H.M.; Li, S.; Klausen, C.; Shi, Z.; Leung, P.C.K. Characterization of the roles of amphiregulin and transforming growth factor β1 in microvasculature-like formation in human granulosa-lutein cells. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 968166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richani, D.; Gilchrist, R.B. The epidermal growth factor network: Role in oocyte growth, maturation and developmental competence. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo, J.L.; Linari, M.; Young, K.A.; Peluffo, M.C. Stromal-derived factor 1 directly promotes genes expressed within the ovulatory cascade in feline cumulus oocyte complexes. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, K.L.; Zhao, H.; Chang, H.M.; Yu, Y.; Qiao, J. Kisspeptin/Kisspeptin Receptor System in the Ovary. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaytan, F.; Garcia-Galiano, D.; Dorfman, M.D.; Manfredi-Lozano, M.; Castellano, J.M.; Dissen, G.A.; Ojeda, S.R.; Tena-Sempere, M. Kisspeptin receptor haplo-insufficiency causes premature ovarian failure despite preserved gonadotropin secretion. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 3088–3097, Erratum in Endocrinology 2015, 156, 3402. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2015-1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellano, J.M.; Gaytan, M.; Roa, J.; Vigo, E.; Navarro, V.M.; Bellido, C.; Dieguez, C.; Aguilar, E.; Sánchez-Criado, J.E.; Pellicer, A.; et al. Expression of KiSS-1 in rat ovary: Putative local regulator of ovulation? Endocrinology 2006, 147, 4852–4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, C.; Zhao, H.; Huang, D. The Role of Kisspeptin in the Control of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis and Reproduction. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 925206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hu, C.; Ye, H.; Luo, R.; Fu, X.; Li, X.; Huang, J.; Chen, W.; Zheng, Y. Inflamm-Aging: A New Mechanism Affecting Premature Ovarian Insufficiency. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 8069898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lliberos, C.; Liew, S.H.; Zareie, P.; La Gruta, N.L.; Mansell, A.; Hutt, K. Evaluation of inflammation and follicle depletion during ovarian ageing in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenti, A.; Tedesco, S.; Boscaro, C.; Trevisi, L.; Bolego, C.; Cignarella, A. Estrogen, Angiogenesis, Immunity and Cell Metabolism: Solving the Puzzle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeliga, A.; Rudnicka, E.; Maciejewska-Jeske, M.; Kucharski, M.; Kostrzak, A.; Hajbos, M.; Niwczyk, O.; Smolarczyk, R.; Meczekalski, B. Neuroendocrine Determinants of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blank, S.K.; McCartney, C.R.; Chhabra, S.; Helm, K.D.; Eagleson, C.A.; Chang, R.J.; Marshall, J.C. Modulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator sensitivity to progesterone inhibition in hyperandrogenic adolescent girls—Implications for regulation of pubertal maturation. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 2360–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Suchta, K.; Grymowicz, M.; Calik-Ksepka, A.; Smolarczyk, K.; Duszewska, A.M.; Smolarczyk, R.; Meczekalski, B. Chronic Low Grade Inflammation in Pathogenesis of PCOS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomi, S.; Barartabar, Z.; Pilehvari, S. The Association Between Increment of Interleukin-1 and Interleukin-6 in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Body Mass Index. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2023, 24, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Yang, M.; Yan, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W. Tenascin C activates the toll-like receptor 4/NF-κB signaling pathway to promote the development of polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, C.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, M.; Shan, H. Oxidative stress and antioxidant imbalance in ovulation disorder in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1018674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spaczynski, R.Z.; Arici, A.; Duleba, A.J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha stimulates proliferation of rat ovarian theca-interstitial cells. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 61, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, F.; Motta, A.; Acosta, M.; Mohamed, F.; Oliveros, L.; Forneris, M. Role of macrophage secretions on rat polycystic ovary: Its effect on apoptosis. Reproduction 2015, 150, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Duan, T.; Zhou, Q. The role of macrophages in reproductive-related diseases. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Q.; Yidong, X.; Xueguang, Z.; Sixian, W.; Wenming, X.; Tao, Z. ETA-mediated anti-TNF-α therapy ameliorates the phenotype of PCOS model induced by letrozole. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, S.; Adorni, M.P.; Ronda, N.; Cappellari, R.; Mioni, R.; Barbot, M.; Pinelli, S.; Plebani, M.; Bolego, C.; Scaroni, C.; et al. Activation profiles of monocyte-macrophages and HDL function in healthy women in relation to menstrual cycle and in polycystic ovary syndrome patients. Endocrine 2019, 66, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soták, M.; Clark, M.; Suur, B.E.; Börgeson, E. Inflammation and resolution in obesity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2025, 21, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Yue, J.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, J.; Tao, T.; Li, S.; Liu, W. Increased serum chemerin concentrations in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: Relationship between insulin resistance and ovarian volume. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 450, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Liu, H.; Xu, C.; Zhang, F. IL-15 Participates in the Pathogenesis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome by Affecting the Activity of Granulosa Cells. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 787876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calan, M.; Kume, T.; Yilmaz, O.; Arkan, T.; Kocabas, G.U.; Dokuzlar, O.; Aygün, K.; Oktan, M.A.; Danıs, N.; Temur, M. A possible link between luteinizing hormone and macrophage migration inhibitory factor levels in polycystic ovary syndrome. Endocr. Res. 2016, 41, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.N.; Li, S.J.; Ding, J.L.; Yin, T.L.; Yang, J.; Ye, H. MIF may participate in pathogenesis of polycystic ovary syndrome in rats through MAPK signalling pathway. Curr. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, R.M.; Park, H.S.; El Andaloussi, A.; Elsharoud, A.; Esfandyari, S.; Ulin, M.; Bakir, L.; Aboalsoud, A.; Ali, M.; Ashour, D.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy ameliorates metabolic dysfunction and restores fertility in a PCOS mouse model through interleukin-10. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, H.C.; Moreno, R.; Rose, D.; Rowland, M.E.; Ciernia, A.V.; Ashwood, P. Impact of maternal immune activation and sex on placental and fetal brain cytokine and gene expression profiles in a preclinical model of neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Neuroinflamm. 2024, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; Viviani, B. Neuromodulatory properties of inflammatory cytokines and their impact on neuronal excitability. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.V.; Rivier, C.L. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines: Actions and mechanisms of action. Physiol. Rev. 1999, 79, 1–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastenbroek, L.J.M.; Kooistra, S.M.; Eggen, B.J.L.; Prins, J.R. The role of microglia in early neurodevelopment and the effects of maternal immune activation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 46, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud, P.; Seferiadis, A.A.; Tyson, L.D.; Zwart, M.F.; Szabo-Rogers, H.L.; Ruhrberg, C.; Liu, K.J.; Baker, C.V. Neural crest origin of olfactory ensheathing glia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21040–21045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, P.E.; Wray, S. Neural crest and olfactory system: New prospective. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, N.; Dong, X.J.; Wang, T.Y.; He, W.J.; Wei, J.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, T.H. Characteristics of olfactory ensheathing cells and microarray analysis in Tupaia belangeri (Wagner, 1841). Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 1819–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.T.; Li, H.; Borch, J.M.; Maksoud, E.; Borneo, J.; Liang, Y.; Quake, S.R.; Luo, L.; Haghighi, P.; Jasper, H. Gut cytokines modulate olfaction through metabolic reprogramming of glia. Nature 2021, 596, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duittoz, A.H.; Forni, P.E.; Giacobini, P.; Golan, M.; Mollard, P.; Negrón, A.L.; Radovick, S.; Wray, S. Development of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone system. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2022, 34, e13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiuk, V.S.; Sharova, V.S.; Zakharova, L.A. Prenatal Inflammation Reprograms Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Development in Female Rats. Inflammation 2025, 48, 2973–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakubo, A.; Jarskog, L.F.; Lieberman, J.A.; Gilmore, J.H. Prenatal exposure to maternal infection alters cytokine expression in the placenta, amniotic fluid, and fetal brain. Schizophr. Res. 2001, 47, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, M.; Toda, H.; Kinoshita, M.; Asai, F.; Nagamine, M.; Shimizu, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Morimoto, Y.; Yoshino, A. Investigation of the impact of preconditioning with lipopolysaccharide on inflammation-induced gene expression in the brain and depression-like behavior in male mice. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 103, 109978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izvolskaia, M.; Ignatiuk, V.; Ismailova, A.; Sharova, V.; Zakharova, L. IgG modulation in male mice with reproductive failure after prenatal inflammation. Reproduction 2021, 161, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galeotti, C.; Kaveri, S.V.; Bayry, J. IVIG-mediated effector functions in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Int. Immunol. 2017, 29, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Carvey, P.M.; Ling, Z. Altered glutathione homeostasis in animals prenatally exposed to lipopolysaccharide. Neurochem. Int. 2007, 50, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Pan, Z.L.; Pang, Y.; Evans, O.B.; Rhodes, P.G. Cytokine induction in fetal rat brains and brain injury in neonatal rats after maternal lipopolysaccharide administration. Pediatr. Res. 2000, 47, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.Y.; Kang, M.J.; Han, J.S. Interleukin-1 beta promotes neuronal differentiation through the Wnt5a/RhoA/JNK pathway in cortical neural precursor cells. Mol. Brain 2018, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, C.I.; Chalon, S.; Cantagrel, S.; Bodard, S.; Andres, C.; Gressens, P.; Saliba, E. Maternal exposure to LPS induces hypomyelination in the internal capsule and programmed cell death in the deep gray matter in newborn rats. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 59, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, R.M.; Lorusso, J.M.; Fletcher, J.; ElTaher, H.; McEwan, F.; Harris, I.; Kowash, H.M.; D’Souza, S.W.; Harte, M.; Hager, R.; et al. Maternal immune activation and role of placenta in the prenatal programming of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuronal Signal. 2023, 7, NS20220064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, S.; Sebire, G. Transplacental Transfer of Interleukin-1 Receptor Agonist and Antagonist Following Maternal Immune Activation. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016, 75, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabás, K.; Barad, Z.; Dénes, Á.; Bhattarai, J.P.; Han, S.K.; Kiss, E.; Sármay, G.; Ábrahám, I.M. The Role of Interleukin-10 in Mediating the Effect of Immune Challenge on Mouse Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neurons In Vivo. eNeuro 2018, 5, ENEURO.0211-18.2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwahara-Otani, S.; Maeda, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Minato, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Yamanishi, K.; Hata, M.; Li, W.; Hayakawa, T.; Noguchi, K.; et al. Interleukin-18 and its receptor are expressed in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of mouse and rat forebrain. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 650, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, K.K.; Zeidler, M.; Kalpachidou, T.; Kress, M. Role of IL-6 in the regulation of neuronal development, survival and function. Cytokine 2021, 144, 155582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, F.; Desiato, G.; Mancinelli, S.; Fossati, G.; Rasile, M.; Morini, R.; Markicevic, M.; Grimm, C.; Amegandjin, C.; Termanini, A.; et al. Prenatal interleukin 6 elevation increases glutamatergic synapse density and disrupts hippocampal connectivity in offspring. Immunity 2021, 54, 2611–2631.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deverman, B.E.; Patterson, P.H. Cytokines and CNS development. Neuron 2009, 64, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.D.; Graham, A.M.; Feczko, E.; Miranda-Dominguez, O.; Rasmussen, J.M.; Nardos, R.; Entringer, S.; Wadhwa, P.D.; Buss, C.; Fair, D.A. Maternal IL-6 during pregnancy can be estimated from newborn brain connectivity and predicts future working memory in offspring. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, G.B.; Yim, Y.S.; Wong, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.V.; Hoeffer, C.A.; Littman, D.R.; Huh, J.R. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 2016, 351, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouihate, A.; Mehdawi, H. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated immune stress in pregnant rats activates STAT3 in the fetal brain: Role of interleukin-6. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.L.; Hsiao, E.Y.; Yan, Z.; Mazmanian, S.K.; Patterson, P.H. The placental interleukin-6 signaling controls fetal brain development and behavior. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2017, 62, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, D.; Norman, A.A.; Woodard, C.L.; Yang, G.; Gauthier-Fisher, A.; Fujitani, M.; Vessey, J.P.; Cancino, G.I.; Sachewsky, N.; Woltjen, K.; et al. Transient maternal IL-6 mediates long-lasting changes in neural stem cell pools by deregulating an endogenous self-renewal pathway. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Li, J.; Garbett, K.; Mirnics, K.; Patterson, P.H. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 10695–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, N.W.; Li, Q.; Mills, C.W.; Ly, J.; Nomura, Y.; Chen, J. Influence of prenatal maternal stress on umbilical cord blood cytokine levels. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2016, 19, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, J.; Samuelsson, A.M.; Jansson, T.; Holmäng, A. Interleukin-6 in the maternal circulation reaches the rat fetus in mid-gestation. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 60, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, P.A.; Dingman, A.L.; Palmer, T.D. Placental TNF-α signaling in illness-induced complications of pregnancy. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 2802–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, P.A.; Haditsch, U.; Braun, A.E.; Cantu, A.V.; Moon, H.M.; Price, R.O.; Anderson, M.P.; Saravanapandian, V.; Ismail, K.; Rivera, M.; et al. Stereotypical alterations in cortical patterning are associated with maternal illness-induced placental dysfunction. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 16874–16888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canetta, S.; Bolkan, S.; Padilla-Coreano, N.; Song, L.J.; Sahn, R.; Harrison, N.L.; Gordon, J.A.; Brown, A.; Kellendonk, C. Maternal immune activation leads to selective functional deficits in offspring parvalbumin interneurons. Mol. Psychiatry 2016, 21, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, K.; Aldo, P.B.; Mor, G. Toll-like receptors and pregnancy: Trophoblast as modulators of the immune response. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2009, 35, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronson, S.L.; Bale, T.L. Prenatal stress-induced increases in placental inflammation and offspring hyperactivity are male-specific and ameliorated by maternal antiinflammatory treatment. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 2635–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakers, F.; Rupprecht, S.; Dreiling, M.; Bergmeier, C.; Witte, O.W.; Schwab, M. Transfer of maternal psychosocial stress to the fetus. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 117, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonakait, G.M. The effects of maternal inflammation on neuronal development: Possible mechanisms. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.G.; Wrammert, J.; Suthar, M.S. Cross-Reactive Antibodies during Zika Virus Infection: Protection, Pathogenesis, and Placental Seeding. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, T.R.; Leeper, N.J.; Hynes, K.L.; Gewertz, B.L. Interleukin-6 causes endothelial barrier dysfunction via the protein kinase C pathway. J. Surg. Res. 2002, 104, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.N.; Jansson, T.; Powell, T.L. IL-6 stimulates system A amino acid transporter activity in trophoblast cells through STAT3 and increased expression of SNAT2. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2009, 297, C1228–C1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, E.Y.; Patterson, P.H. Activation of the maternal immune system induces endocrine changes in the placenta via IL-6. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, D. The unsolved enigmas of leukemia inhibitory factor. Stem Cells 2003, 21, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, S.; Webster, J.; Ren, S.G.; Takino, H.; Said, J.; Zand, O.; Melmed, S. Human and murine pituitary expression of leukemia inhibitory factor. Novel intrapituitary regulation of adrenocorticotropin hormone synthesis and secretion. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 95, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, S.; Readhead, C.; Stefaneanu, L.; Fine, J.; Tampanaru-Sarmesiu, A.; Kovacs, K.; Melmed, S. Pituitary-directed leukemia inhibitory factor transgene forms Rathke’s cleft cysts and impairs adult pituitary function. A model for human pituitary Rathke’s cysts. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2462–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, H.; Readhead, C.; Nakashima, M.; Ren, S.G.; Melmed, S. Pituitary-directed leukemia inhibitory factor transgene causes Cushing’s syndrome: Neuro-immune-endocrine modulation of pituitary development. Mol. Endocrinol. 1998, 12, 1708–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimber, S.J. Leukaemia inhibitory factor in implantation and uterine biology. Reproduction 2005, 130, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magni, P.; Dozio, E.; Ruscica, M.; Watanobe, H.; Cariboni, A.; Zaninetti, R.; Motta, M.; Maggi, R. Leukemia inhibitory factor induces the chemomigration of immortalized gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons through the independent activation of the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellularly regulated kinase 1/2, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathways. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007, 21, 1163–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dozio, E.; Ruscica, M.; Galliera, E.; Corsi, M.M.; Magni, P. Leptin, ciliary neurotrophic factor, leukemia inhibitory factor and interleukin-6: Class-I cytokines involved in the neuroendocrine regulation of the reproductive function. Curr. Protein. Pept. Sci. 2009, 10, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddie, S.L.; Childs, A.J.; Jabbour, H.N.; Anderson, R.A. Developmentally regulated IL6-type cytokines signal to germ cells in the human fetal ovary. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 18, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Gearing, D.P.; White, L.S.; Compton, D.L.; Schooley, K.; Donovan, P.J. Role of leukemia inhibitory factor and its receptor in mouse primordial germ cell growth. Development 1994, 120, 3145–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simamura, E.; Shimada, H.; Higashi, N.; Uchishiba, M.; Otani, H.; Hatta, T. Maternal leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) promotes fetal neurogenesis via a LIF-ACTH-LIF signaling relay pathway. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, N.; Jeong, K.H.; Yano, S.; Huang, S.; Pang, J.L.; Ren, X.; Terwilliger, E.; Kaiser, U.B.; Vassilev, P.M.; Pollak, M.R.; et al. Calcium receptor stimulates chemotaxis and secretion of MCP-1 in GnRH neurons in vitro: Potential impact on reduced GnRH neuron population in CaR-null mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 292, E523–E532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liverman, C.S.; Kaftan, H.A.; Cui, L.; Hersperger, S.G.; Taboada, E.; Klein, R.M.; Berman, N.E. Altered expression of pro-inflammatory and developmental genes in the fetal brain in a mouse model of maternal infection. Neurosci. Lett. 2006, 399, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobini, P.; Giampietro, C.; Fioretto, M.; Maggi, R.; Cariboni, A.; Perroteau, I.; Fasolo, A. Hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor facilitates migration of GN-11 immortalized LHRH neurons. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 3306–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gutierrez, H.; Dolcet, X.; Tolcos, M.; Davies, A. HGF regulates the development of cortical pyramidal dendrites. Development 2004, 131, 3717–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobini, P.; Messina, A.; Wray, S.; Giampietro, C.; Crepaldi, T.; Carmeliet, P.; Fasolo, A. Hepatocyte growth factor acts as a motogen and guidance signal for gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone-1 neuronal migration. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, S.H.; Boehm, U.; Herbison, A.E.; Campbell, R.E. Conditional Viral Tract Tracing Delineates the Projections of the Distinct Kisspeptin Neuron Populations to Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Neurons in the Mouse. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2582–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robertson, S.A.; Skinner, R.J.; Care, A.S. Essential role for IL-10 in resistance to lipopolysaccharide-induced preterm labor in mice. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 4888–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estienne, A.; Brossaud, A.; Reverchon, M.; Ramé, C.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Adipokines Expression and Effects in Oocyte Maturation, Fertilization and Early Embryo Development: Lessons from Mammals and Birds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briffa, J.F.; O’Dowd, R.; Moritz, K.M.; Romano, T.; Jedwab, L.R.; McAinch, A.J.; Hryciw, D.H.; Wlodek, M.E. Uteroplacental insufficiency reduces rat plasma leptin concentrations and alters placental leptin transporters: Ameliorated with enhanced milk intake and nutrition. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3389–3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, E.; Duval, F.; Vialard, F.; Dieudonné, M.N. The roles of leptin and adiponectin at the fetal-maternal interface in humans. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 24, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mela, V.; Díaz, F.; Gertler, A.; Solomon, G.; Argente, J.; Viveros, M.P.; Chowen, J.A. Neonatal treatment with a pegylated leptin antagonist has a sexually dimorphic effect on hypothalamic trophic factors and neuropeptide levels. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 24, 756–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udagawa, J.; Hatta, T.; Hashimoto, R.; Otani, H. Roles of leptin in prenatal and perinatal brain development. Congenit. Anom. 2007, 47, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wen, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y. Prenatal Lipopolysaccharide Exposure Promotes Dyslipidemia in the Male Offspring Rats. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Yao, D.; Wang, T.; Shen, Q.; Li, W.; Li, B.; Ding, X.; Liu, Z. Prenatal inflammation causes obesity and abnormal lipid metabolism via impaired energy expenditure in male offspring. Nutr. Metab. 2022, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, D.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Lai, W.; Huang, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, X.; Li, X. TLR2-Deficiency Promotes Prenatal LPS Exposure-Induced Offspring Hyperlipidemia. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroga, S.; Juárez, Y.R.; Marcone, M.P.; Vidal, M.A.; Genaro, A.M.; Burgueño, A.L. Prenatal stress promotes insulin resistance without inflammation or obesity in C57BL/6J male mice. Stress 2021, 24, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briffa, J.F.; McAinch, A.J.; Romano, T.; Wlodek, M.E.; Hryciw, D.H. Leptin in pregnancy and development: A contributor to adulthood disease? Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 308, E335–E350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cytokine | Hypothalamic Level (GnRH) | Pituitary-Level Pituitary Gonadotropins | Gonadal-Level Steroids/Gametogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL1β | Suppression of GnRH secretion in the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus. LH surge suppression in females. Suppressive effect is mediated by an increased synthesis and secretion of GABA and a decreased norepinephrine concentration. | Suppression of LH/FSH secretion in response to GnRH. | Low doses stimulate Leydig cell proliferation High doses suppress Leydig cell steroidogenesis Reduces gonadotropin receptor expression on granulosa cells. |

| TNFα | Suppression of GnRH synthesis and secretion during acute and chronic inflammation in obesity or aging via KISS1 and dynorphin-expressing neurons. Suppression of KISS1 receptor expression on GnRH neurons. | Suppressive effect on LH secretion via GnRH pulse regulation. | TNFα is synthesized by testicular macrophages and spermatids and is essential for Leydig cell viability and steroidogenesis. Stimulates androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells Suppresses anti-Müllerian hormone synthesis in them. Elevated TNFα levels suppress steroidogenesis. TNF suppresses aromatase expression in cumulus cells and adipose tissue, suppressing testosterone to estradiol conversion. TNF induces granulosa cell apoptosis and mediates ovulation. |

| IL-6 | In adults, evidence of IL-6 effects on GnRH neurons is insufficient. In fetus, IL-6 is essential for axonal growth regulation. IL-6 elevation suppresses GnRH neuron migration into the fetal brain. | Stimulates the secretion of LH and FSH and pituitary cell proliferation. | Dose-dependent suppression of the steroidogenic function of Leydig cells, regulation of their viability. Regulates permeability of blood–testis barrier. In ovary, IL-6 mediates ovulation. |

| LIF | In adults, LIF stimulates GnRH secretion In fetus, LIF stimulates GnRH neuron chemotaxis. | Regulates fetal pituitary cell differentiation pathway. | LIF is essential for germ cell proliferation. |

| IFNγ | Evidence is insufficient. IFNγ stimulates monoaminergic activity in paraventricular nucleus, which regulates GnRH neuron activity. | TNFα suppresses pituitary hormone response to hypothalamic releasing hormones, including GnRH; Receptors for TNFα are found on endocrine cells of the anterior pituitary. | IFN induces granulosa cell apoptosis. |

| IL-2 | Data is insufficient. | Suppression of LH and FSH secretion Stimulation of ACTH and thyreotropin secretion. | Data is insufficient. |

| IL-8 | Data is insufficient. | IL-8 deficiency leads to LH and FSH deficiency. | Enhances Leydig cell viability and growth. |

| IL-10 | GnRH neurons express IL-10 receptor. | Evidence of IL-10 action mechanism in estrous cyclicity maintenance is insufficient. | IL-10 deficiency is associated with estrous cyclicity suppression and disorders of fertilization and gestation. |

| Activin, inhibin, follistatin | Activin, inhibin and follistatin balance regulates KISS1 expression. | Activin stimulates FSH synthesis, while follistatin suppresses it. | Activin regulates the response of Sertoli cells to FSH. The balance of activin and inhibin expression by Sertoli cells depends on the stage of spermatogenic epithelium development. |

| Leptin | Leptin receptor is not found on GnRH neurons. Leptin regulates GnRH neurons via premamillary neurons connected with KISS1 neurons. | Leptin and other adipokine receptors are found on gonadotropocytes. | Suppression of testosterone secretion in testes. Suppression and stimulation of follicle growth depending on its concentration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ignatiuk, V.M.; Sharova, V.S.; Zakharova, L.A. The Role of Cytokines in the Development and Functioning of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axis in Mammals in Normal and Pathological Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211057

Ignatiuk VM, Sharova VS, Zakharova LA. The Role of Cytokines in the Development and Functioning of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axis in Mammals in Normal and Pathological Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211057

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgnatiuk, Vasilina M., Viktoria S. Sharova, and Liudmila A. Zakharova. 2025. "The Role of Cytokines in the Development and Functioning of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axis in Mammals in Normal and Pathological Conditions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211057

APA StyleIgnatiuk, V. M., Sharova, V. S., & Zakharova, L. A. (2025). The Role of Cytokines in the Development and Functioning of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Gonadal Axis in Mammals in Normal and Pathological Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11057. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211057