Intracellular Transport of Monomeric Peptides, (Poly)Peptide-Based Coacervates and Fibrils: Mechanisms and Prospects for Drug Delivery

Abstract

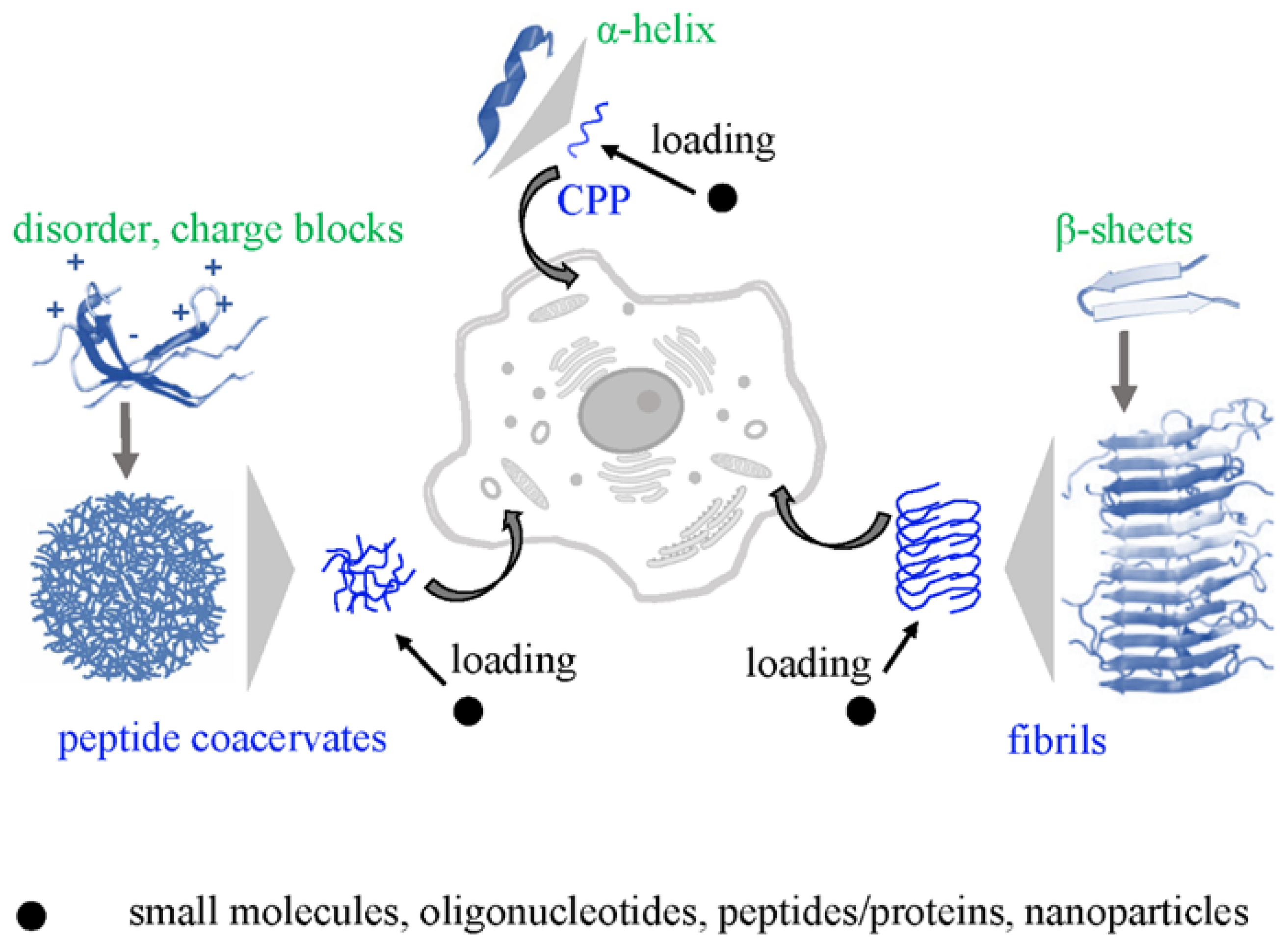

1. Introduction

- Monomeric/oligomeric cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs);

- Multimeric dense but liquid peptide associates, termed coacervates;

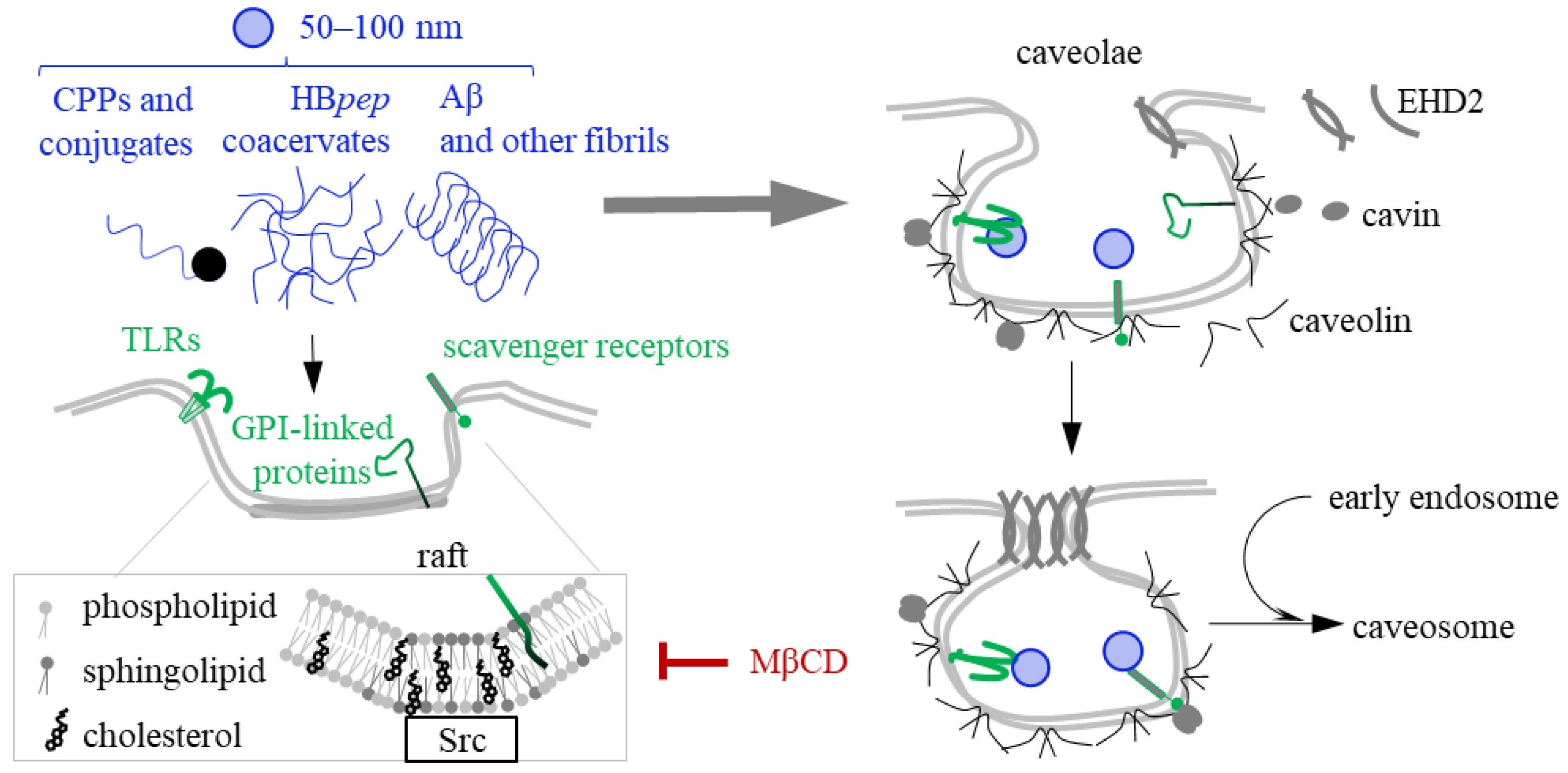

- Multimeric solid aggregates, including cross-beta structures (fibrils).

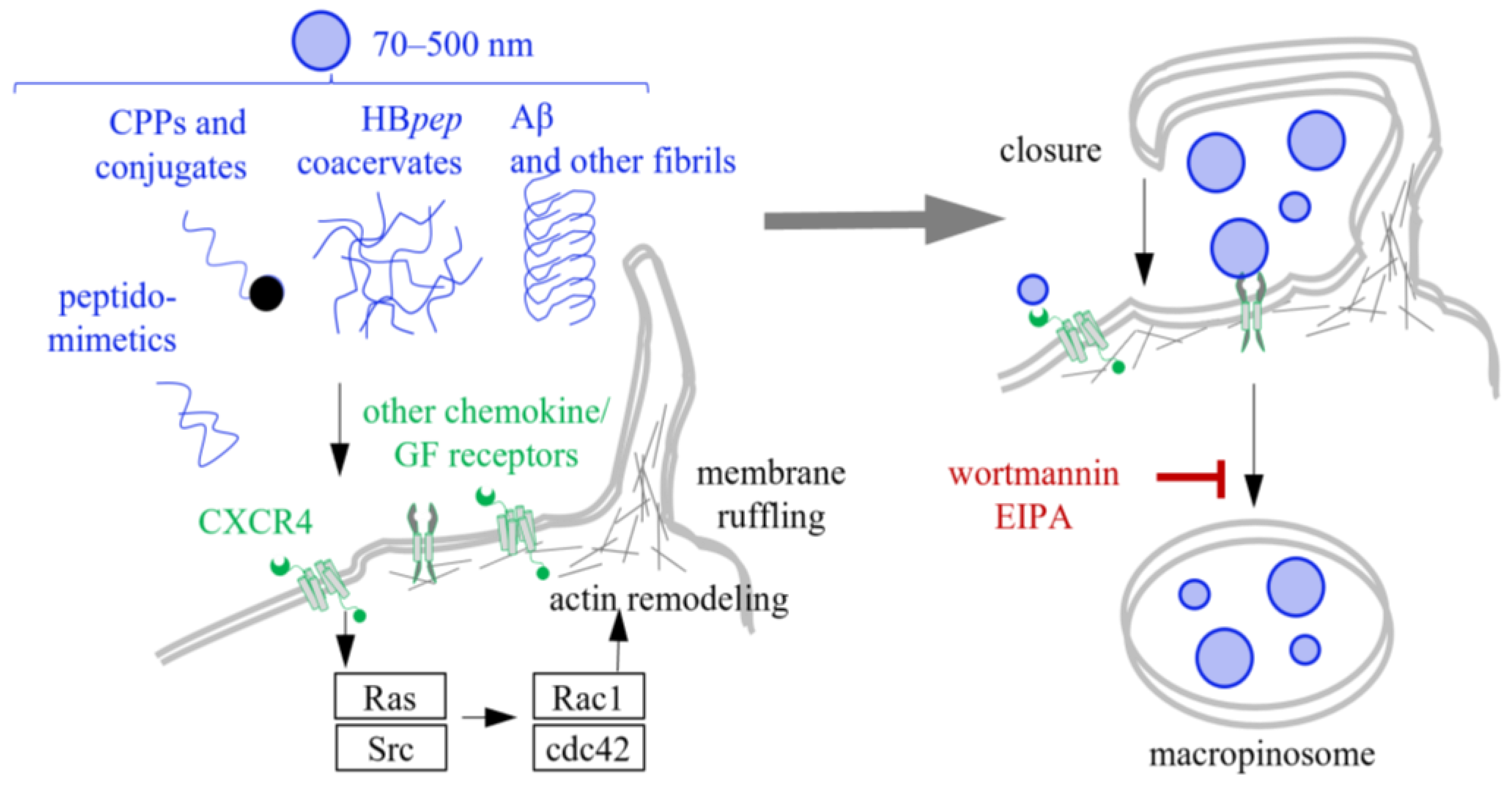

2. Cell Penetrating Peptides (CPPs), Coacervates and Fibrils

3. Direct Intracellular Transport of CPPs and Fibril Transport Through Tunneling Nanotubes (TNTs)

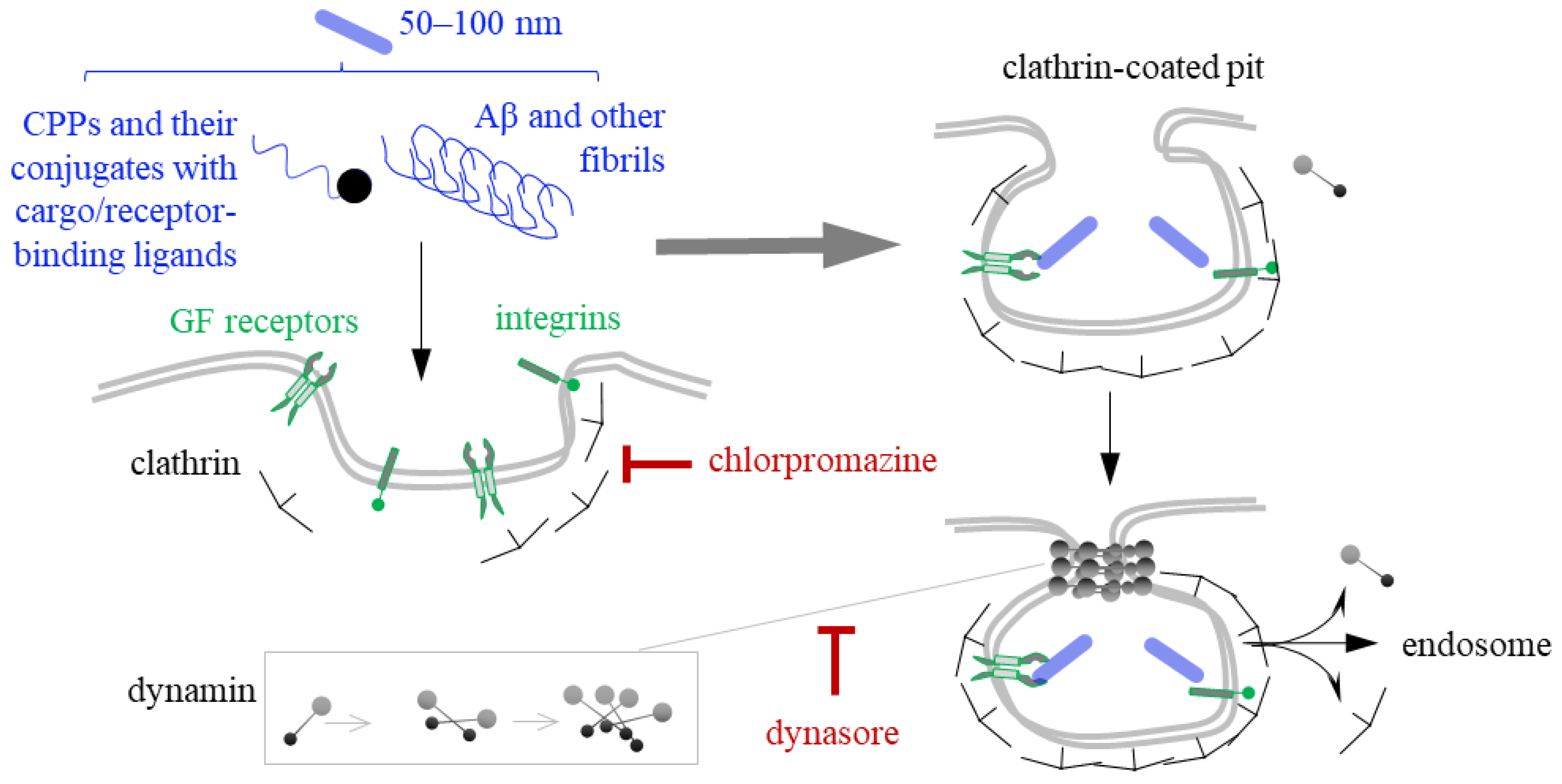

4. Clathrin- and Dynamin-Mediated Endocytosis of CPPs and Fibrils

5. Caveolin- and Raft-Mediated Endocytosis of CPPs, Coacervates and Fibrils

6. Macropinocytosis of CPPs, Coacervates and Fibrils

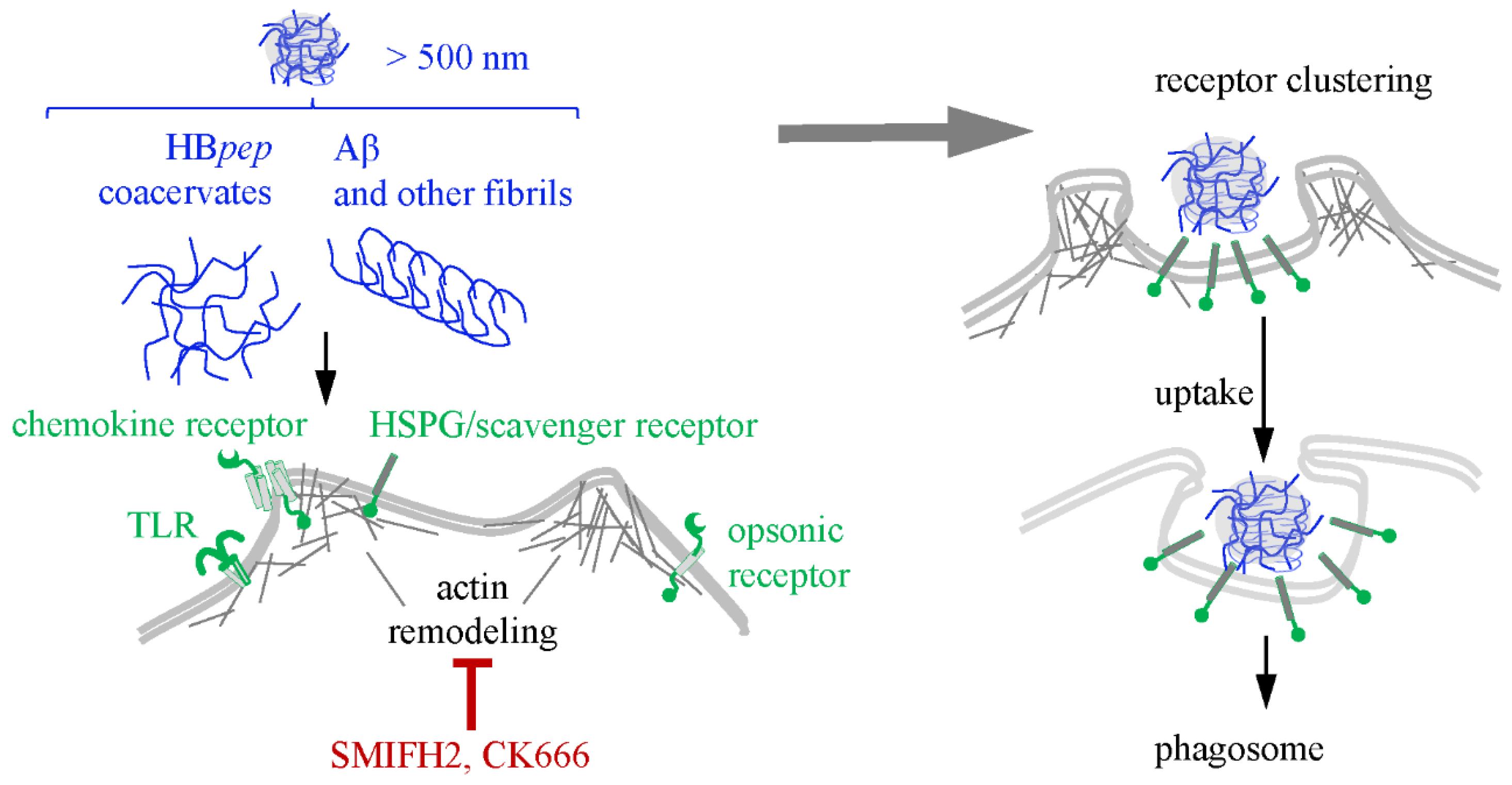

7. Phagocytosis of Condensates and Fibrils

8. Open Questions and Limitations the Internalization Studies

| Pathway | CPPs | Coacervates | Fibrils | Inhibitor (Inhibited Pathway Step) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct and TNT-dependent transport | Penetratin [97,112]; TAT [97,102]; oligo-R (R9) [97,101,102,107]; MPG [22]; Pep-1 [22]; TP10 [111]; mR8 [101] | sELP-ON [185] and probably others [215] * | α-syn [115,118]; Tau [114]; β-amyloid [114] | Cytochalasin B (actin polymerization for TNT formation) [146,147] |

| Clathrin- and dynamin-mediated endocytosis | Oligo-R (R8) [242]; TAT [122]; TP10 [243] and its phosphorylated derivatives [135]; P-rich (XZZ)3 [23] | - | α-syn [119]; Tau [142]; β-amyloid [142]; Huntingtin [143] | Chlorpromazine (clathrin assembly [132]) and dynasore (GTP-dependent dynamin polymerization [133]) |

| Caveolin- and raft-mediated endocytosis | TAT [172,244]; TP10 [174] | HBpep [182,183]; (GHGLY)4 and (GHGVY)4 [60] | α-syn [144,150,245]; PrPSc [246]; Tau [149]; β-amyloid [149] | MβCD (cholesterol-driven raft formation [165]) |

| Macropinocytosis | TAT [122,207]; oligo-R (R8) [122,208,209]; oligo-R (R12) [203]; PF14 [24] | HBpep [214]; (RRASL)1–3 [184]; sELP-ON [185] | α-syn [217]; Tau [142,216,217]; β-amyloid [217]; Huntingtin [143] | Amiloride and EIPA (pH control by Na+/H+ exchangers that enables membrane remodeling [212]) and wortmannin (PI3K activity that enables diacylglycerol- and Ras-dependent membrane remodeling [213]) |

| Phagocytosis | - | HBpep [181] | β-amyloid [232]; α-syn [230] | SMIFH2 (formin-dependent actin polymerization [227,228]) and CK666 (Arp2/3-dependent nucleation of actin polymerization [229]) |

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPP | Cell-penetrating peptide |

| TAT | HIV transactivator of transcription |

| pANTP | Penetratin |

| LLPS | liquid–liquid phase separation |

| TNT | Tunneling nanotube |

| CME | Clathrin-mediated endocytosis |

| CvME | Caveolin-mediated endocytosis |

| HSPG | Heparan sulfate proteoglycan |

| MβCD | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin |

| GPI | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol |

| EHD2 | EH domain-containing protein 2 |

| LAG3 | Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| Cdc42 | Cell division control protein 42 |

| EIPA | Ethylisopropylamiloride |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases |

References

- Wang, L.; Wang, N.; Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Yan, Z.; Shao, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Fu, C. Therapeutic peptides: Current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Malviya, G.; Chottova Dvorakova, M. Role of peptides in diagnostics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trier, N.H.; Houen, G. Design, Production, Characterization, and Use of Peptide Antibodies. Antibodies 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Shi, J. Advance in peptide-based drug development: Delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Foster, A.; Tavassoli, A. Methods for generating and screening libraries of genetically encoded cyclic peptides in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2020, 4, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, J.T.; Liu, W.R. Diversification of Phage-Displayed Peptide Libraries with Noncanonical Amino Acid Mutagenesis and Chemical Modification. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6051–6077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, C.; Ren, Y.; Yang, C.; Tian, F. Computational Peptidology: A New and Promising Approach to Therapeutic Peptide Design. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Palepu, K.; Hong, L.; Mao, J.; Ye, T.; Iyer, R.; Zhao, L.; Chen, T.; Vincoff, S.; Watson, R.; et al. De novo design of peptide binders to conformationally diverse targets with contrastive language modeling. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lin, H.; Bai, R.; Duan, H. Deep learning for advancing peptide drug development: Tools and methods in structure prediction and design. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 268, 116262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.; Vosough, P.; Taghizadeh, S.; Savardashtaki, A. Therapeutic peptide development revolutionized: Harnessing the power of artificial intelligence for drug discovery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorachinov, F.; Mraiche, F.; Moustafa, D.A.; Hishari, O.; Ismail, Y.; Joseph, J.; Crcarevska, M.S.; Dodov, M.G.; Geskovski, N.; Goracinova, K. Nanotechnology—A robust tool for fighting the challenges of drug resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2023, 14, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, G.; O’Hare, P. Intercellular Trafficking and Protein Delivery by a Herpesvirus Structural Protein. Cell 1997, 88, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, D. Frankel Cellular Uptake of the Tat Protein from Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Cell 1988, 55, 1189–1193. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.; Loewenstein, P.M. Autonomous Functional Domains of Chemically Synthesized Human lmmunodeficiency Virus Tat Trans-Activator Protein. Cell 1988, 55, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadés-Alcaraz, A.; Reinosa, R.; Holguín, Á. HIV Transmembrane Glycoprotein Conserved Domains and Genetic Markers Across HIV-1 and HIV-2 Variants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 855232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyman, T.B.; Nicol, F.; Zelphati, O.; Scaria, P.V.; Plank, C.; Szoka, F.C. Design, synthesis, and characterization of a cationic peptide that binds to nucleic acids and permeabilizes bilayers. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 3008–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niidome, T.; Takaji, K.; Urakawa, M.; Ohmori, N.; Wada, A.; Hirayama, T.; Aoyagi, H. Chain length of cationic alpha-helical peptide sufficient for gene delivery into cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 1999, 10, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derossi, D.; Joliot, A.H.; Chassaing, G.; Prochiantz, A. The third helix of the Antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 10444–10450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareh, D.; Nekounam Ghadirli, R.; Hao, Z.; Paimard, G.; Alinejad, T. The Role of Fibroblast Growth Factors in Viral Replication: FGF-2 as a Key Player. In Viral Replication and Production; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyle, C.L.; Stephens, P.E.; Humphreys, D.P.; Heywood, S.; Cain, K.; Bulleid, N.J. IgG light chain-independent secretion of heavy chain dimers: Consequence for therapeutic antibody production and design. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 3179–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soomets, U.; Lindgren, M.; Gallet, X.; Hällbrink, M.; Elmquist, A.; Balaspiri, L.; Zorko, M.; Pooga, M.; Brasseur, R.; Langel, Ü. Deletion analogues of transportan. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1467, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.C.; Deshayes, S.; Heitz, F.; Divita, G. Cell-penetrating peptides: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Biol. Cell 2008, 100, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Wennemers, H. Amphipathic Proline-Rich Cell Penetrating Peptides for Targeting Mitochondria. ACS Chem. Biol. 2025, 20, 2298–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, K.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Zaghloul, E.M.; Lehto, T.; Lindberg, S.; Moreno, P.M.; Viola, J.R.; Magdy, T.; Abdo, R.; Guterstam, P.; et al. PepFect 14, a novel cell-penetrating peptide for oligonucleotide delivery in solution and as solid formulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 5284–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kam, A.; Loo, S.; Fan, J.S.; Sze, S.K.; Yang, D.; Tam, J.P. Roseltide rT7 is a disulfide-rich, anionic, and cell-penetrating peptide that inhibits proteasomal degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19604–19615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.B.; Christov, K.; Mander, S.; Green, A.; Shilkaitis, A.; Das Gupta, T.K.; Yamada, T. Intracellular redistribution of cell-penetrating peptide p28: A mechanism for enhanced anti-cancer activity. J. Control. Release 2025, 382, 113660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalafatovic, D.; Giralt, E. Cell-penetrating peptides: Design strategies beyond primary structure and amphipathicity. Molecules 2017, 22, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhova, D.I.; Golovicheva, V.V.; Fatkhudinov, T.K.; Shevtsova, Y.A.; Soboleva, A.G.; Goryunov, K.V.; Dyakonov, A.S.; Mokroysova, V.O.; Mingaleva, N.S.; Shedenkova, M.O.; et al. Therapeutic Efficiency of Proteins Secreted by Glial Progenitor Cells in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowski, A.M.; Ensign, M.A.; Maisel, K. Cell-penetrating peptides as facilitators of cargo-specific nanocarrier-based drug delivery. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 20006–20019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiwarangkool, S.; Akita, H.; Nakatani, T.; Kusumoto, K.; Kimura, H.; Suzuki, M.; Nishimura, M.; Sato, Y.; Harashima, H. PEGylation of the GALA Peptide Enhances the Lung-Targeting Activity of Nanocarriers That Contain Encapsulated siRNA. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 106, 2420–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, C.; de Heus, C.; Faber, L.; ten Brink, C.; Potze, L.; Fermie, J.; Liv, N.; Klumperman, J. An adapted protocol to overcome endosomal damage caused by polyethylenimine (PEI) mediated transfections. Matters 2017, 129, e201711000012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, H.J.; El-Andaloussi, S.; Holm, T.; Mäe, M.; Jänes, J.; Maimets, T.; Langel, Ü. Characterization of a novel cytotoxic cell-penetrating peptide derived from p14ARF protein. Mol. Ther. 2008, 16, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derossi, D.; Calvet, S.; Trembleau, A.; Brunissen, A.; Chassaing, G.; Prochiantz, A. Cell internalization of the third helix of the antennapedia homeodomain is receptor-independent. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 18188–18193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komin, A.; Bogorad, M.I.; Lin, R.; Cui, H.; Searson, P.C.; Hristova, K. A peptide for transcellular cargo delivery: Structure-function relationship and mechanism of action. J. Control. Release 2020, 324, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konate, K.; Josse, E.; Tasic, M.; Redjatti, K.; Aldrian, G.; Deshayes, S.; Boisguérin, P.; Vivès, E. WRAP-based nanoparticles for siRNA delivery: A SAR study and a comparison with lipid-based transfection reagents. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmani, S.; Dixon, J.E. Oral delivery of anti-diabetes therapeutics using cell penetrating and transcytosing peptide strategies. Peptides 2018, 100, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Luo, Y.; Shibu, M.A.; Toth, I.; Skwarczynskia, M. Cell-penetrating Peptides: Efficient Vectors for Vaccine Delivery. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2019, 16, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del’Guidice, T.; Lepetit-Stoffaes, J.P.; Bordeleau, L.J.; Roberge, J.; Théberge, V.; Lauvaux, C.; Barbeau, X.; Trottier, J.; Dave, V.; Roy, D.C.; et al. Membrane permeabilizing amphiphilic peptide delivers recombinant transcription factor and CRISPR-Cas9/Cpf1 ribonucleoproteins in hard-to-modify cells. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Jia, P.; Cong, L.; Li, J.; Duan, Y.; Ke, F.; Zhang, F.; et al. Cell-penetrating peptide: A powerful delivery tool for DNA-free crop genome editing. Plant Sci. 2022, 324, 111436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, A.A.; Weber, C.A.; Jülicher, F. Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.W.; Holehouse, A.S.; Peran, I.; Farag, M.; Incicco, J.J.; Bremer, A.; Grace, C.R.; Soranno, A.; Pappu, R.V.; Mittag, T. Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science 2020, 367, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Guo, Q.; Yu, J. Bio-inspired functional coacervates: Special Issue: Emerging Investigators. Aggregate 2022, 3, e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, T.; Iso, N.; Norizoe, Y.; Sakaue, T.; Yoshimura, S.H. Charge block-driven liquid–liquid phase separation–mechanism and biological roles. J. Cell Sci. 2024, 137, jcs261394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcherds, W.; Bremer, A.; Borgia, M.B.; Mittag, T. How do intrinsically disordered protein regions encode a driving force for liquid-liquid phase separation? Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 67, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruch Leshem, A.; Sloan-Dennison, S.; Massarano, T.; Ben-David, S.; Graham, D.; Faulds, K.; Gottlieb, H.E.; Chill, J.H.; Lampel, A. Biomolecular condensates formed by designer minimalistic peptides. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Zhou, P.; Shen, G.; Ivanov, T.; Yan, X.; Landfester, K.; Caire da Silva, L. Binary peptide coacervates as an active model for biomolecular condensates. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laflamme, G.; Mekhail, K. Biomolecular condensates as arbiters of biochemical reactions inside the nucleus. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Dai, S.; Xie, Z.; Lu, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhou, R.; Du, Y.; Tian, B. Polyphosphate- and Antioxidant Peptide-Based Coacervate Delivers miRNA. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 34951–34964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Lau, S.Y.; Lim, Z.W.; Chang, S.C.; Ghadessy, F.; Partridge, A.; Miserez, A. Phase-separating peptides for direct cytosolic delivery and redox-activated release of macromolecular therapeutics. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermakova, K.; Hodges, H.C. Interaction modules that impart specificity to disordered protein. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Z.W.; Ping, Y.; Miserez, A. Glucose-Responsive Peptide Coacervates with High Encapsulation Efficiency for Controlled Release of Insulin. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2176–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lim, Z.W.; Guo, Q.; Yu, J.; Miserez, A. Liquid–liquid phase separation of proteins and peptides derived from biological materials: Discovery, protein engineering, and emerging applications. MRS Bull. 2020, 45, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumiller, W.M.; Keating, C.D. Phosphorylation-mediated RNA/peptide complex coacervation as a model for intracellular liquid organelles. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Liese, S.; Schoenmakers, L.; Weber, C.A.; Suzuki, H.; Huck, W.T.S.; Spruijt, E. Endocytosis of Coacervates into Liposomes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 13451–13455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Hu, X.; van Haren, M.H.I.; Spruijt, E.; Huck, W.T.S. Structure-Property Relationships Governing Membrane-Penetrating Behaviour of Complex Coacervates. Small 2023, 19, e2303138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imayoshi, A.; Yokoo, H.; Kawaguchi, M.; Tsubaki, K.; Oba, M. Visualization of the Plasmid DNA Delivery System by Complementary Fluorescence Labeling of Arginine-Rich Peptides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2024, 72, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fang, H.; Zhu, W.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Qian, X. Dynamic Compartmentalization of Peptide–Oligonucleotide Conjugates with Reversible Nanovesicle–Microdroplet Phase Transition Behaviors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 36998–37008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, L.; Chew, W.L.; Ping, Y.; Miserez, A. Redox-Responsive Phase-Separating Peptide as a Universal Delivery Vehicle for CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing Machinery. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 16597–16606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, U.; Das, A.; Brown, E.M.; Struckman, H.L.; Wang, H.; Stealey, S.; Sprunger, M.L.; Wasim, A.; Fascetti, J.; Mondal, J.; et al. Histidine-rich enantiomeric peptide coacervates enhance antigen sequestration and presentation to T cells. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 7523–7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, R.; Ranson, N.A.; Radford, S.E. Amyloid structures: Much more than just a cross-β fold. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2020, 60, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, C. Structural Diversity of Amyloid Fibrils and Advances in Their Structure Determination. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xu, T.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Melcher, K.; Xu, H.E. Amyloid beta: Structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 1205–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, C.; Luo, F.; Liu, Z.; Gui, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Li, X. Amyloid fibril structure of α-synuclein determined by cryo-electron microscopy. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V.M.-Y.; Balin, B.J.; Otvos, L.; Trojanowski, J.Q. A68: A Major Subunit of Paired Helical Filaments and Derivatized Forms of Normal Tau. Science 1991, 251, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mammeri, N.; Duan, P.; Dregni, A.J.; Hong, M. Amyloid fibril structures of tau: Conformational plasticity of the second microtubule-binding repeat. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadh4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherzinger, E.; Sittler, A.; Schweiger, K.; Heiser, V.; Lurz, R.; Hasenbank, R.; Bates, G.P.; Lehrach, H.; Wanker, E.E. Self-assembly of polyglutamine-containing huntingtin fragments into amyloid-like fibrils: Implications for Huntington’s disease pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4604–4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yang, F.; Yu, H.; Xie, Y.; Yao, W. Lysozyme amyloid fibril: Regulation, application, hazard analysis, and future perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stöhr, J.; Weinmann, N.; Wille, H.; Kaimann, T.; Nagel-Steger, L.; Birkmann, E.; Panza, G.; Prusiner, S.B.; Eigen, M.; Riesner, D. Mechanisms of prion protein assembly into amyloid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2409–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.; Sawaya, M.R.; Balbirnie, M.; Madsen, A.Ø.; Riekel, C.; Grothe, R.; Eisenberg, D. Structure of the cross-β spine of amyloid-like fibrils. Nature 2005, 435, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, M.; Kalhor, H.R.; Laurent, S.; Lynch, I. Protein fibrillation and nanoparticle interactions: Opportunities and challenges. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunde, M.; Blake, C. The Structure of Amyloid Fibrils by Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Diffraction. Adv. Protein. Chem. 1997, 50, 123–159. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Han, S.; Guan, S.; Zhang, R.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Han, L.; Tan, Z.; Du, M.; Li, T. Preparation, design, identification and application of self-assembly peptides from seafood: A review. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Robang, A.S.; Sarma, S.; Le, J.V.; Helmicki, M.E.; Lambert, M.J.; Guerrero-Ferreira, R.; Arboleda-Echavarria, J.; Paravastu, A.K.; Hall, C.K. Sequence patterns and signatures: Computational and experimental discovery of amyloid-forming peptides. PNAS Nexus 2022, 1, pgac263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, K.J.; Cyr, D.M. Amyloid in neurodegenerative diseases: Friend or foe? Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011, 22, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.K.; Schubert, D.; Rivier, C.; Lee, S.; Rivier, J.E.; Riek, R. Amyloid as a Depot for the Formulation of Long-Acting Drugs. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankar, S.; Anoop, A.; Sen, S.; Maji, S.K. Nanomaterials: Amyloids reflect their brighter side. Nano Rev. 2011, 2, 6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, H.; Qin, X. Amyloid Fibrils and Their Applications: Current Status and Latest Developments. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmadana, D.; Reynolds, N.P.; Conn, C.E.; Valéry, C. pH-Dependent Self-Assembly of Human Neuropeptide Hormone GnRH into Functional Amyloid Nanofibrils and Hexagonal Phases. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 2019, 2, 3601–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusova, V.; Vus, K.; Tarabara, U.; Zhytniakivska, O.; Deligeorgiev, T.; Gorbenko, G. Liposomes Integrated with Amyloid Hydrogels: A Novel Composite Drug Delivery Platform. Bionanoscience 2020, 10, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cai, Z.; Chen, Q.; Liu, M.; Ye, L.; Ren, J.; Liao, W.; Liu, S. Engineering β-sheet peptide assemblies for biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci. 2016, 4, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Lopus, M.; Kishore, N. From Self-Assembly to Drug Delivery: Understanding and Exploring Protein Fibrils. Langmuir 2025, 41, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, S.; Paul, S.; Srivastava, A.; Pastor, A.; Kundu, B.; Chaudhuri, T.K. Stable self-assembled nanostructured hen egg white lysozyme exhibits strong anti-proliferative activity against breast cancer cells. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 130, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, J.S.; Tian, Y.F.; Jung, J.P.; Collier, J.H. A self-assembling peptide acting as an immune adjuvant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesson, C.B.; Huelsmann, E.J.; Lacek, A.T.; Kohlhapp, F.J.; Webb, M.F.; Nabatiyan, A.; Zloza, A.; Rudra, J.S. Antigenic peptide nanofibers elicit adjuvant-free CD8+ T cell responses. Vaccine 2014, 32, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVay, B.; Wolfe, D.; Ramamoorthy, A. Functional Amyloids as Multifunctional Platforms for Targeted Drug Delivery and Immunotherapy. Langmuir 2025, 41, 25849–25867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabrodskaya, Y.; Sivak, K.; Sergeeva, M.; Aleksandrov, A.; Kalinina, E.; Taraskin, A.; Eropkin, M.; Eropkina, E.; Egorov, V. Peptide fibrils as a vaccine: Proof of concept. J. Immunol. Methods 2025, 538, 113811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaknin, A.; Grossman, A.; Durham, N.D.; Lupovitz, I.; Goren, S.; Golani, G.; Roichman, Y.; Munro, J.B.; Sorkin, R. Ebola Virus Glycoprotein Strongly Binds to Membranes in the Absence of Receptor Engagement. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, D. Designing immunogenic peptides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 749–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.R.; Koşaloğlu-Yalçın, Z.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. A large-scale study of peptide features defining immunogenicity of cancer neo-epitopes. NAR Cancer 2024, 6, zcae002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achilleos, K.; Petrou, C.; Nicolaidou, V.; Sarigiannis, Y. Beyond Efficacy: Ensuring Safety in Peptide Therapeutics through Immunogenicity Assessment. J. Pept. Sci. 2025, 31, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, M.; Shubow, S. Immunogenicity of therapeutic peptide products: Bridging the gaps regarding the role of product-related risk factors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1608401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakeri-Milani, P.; Najafi-Hajivar, S.; Sarfraz, M.; Nokhodchi, A.; Mohammadi, H.; Montazersaheb, S.; Niazi, M.; Hemmatzadeh, M.; Soleymani-Goloujeh, M.; Baradaran, B.; et al. Cytotoxicity and Immunogenicity Evaluation of Synthetic Cell-penetrating Peptides for Methotrexate Delivery. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 20, 506–515. [Google Scholar]

- Dupont, E.; Prochiantz, A.; Joliot, A. Identification of a signal peptide for unconventional secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 8994–9000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardozo, A.K.; Buchillier, V.; Mathieu, M.; Chen, J.; Ortis, F.; Ladrière, L.; Allaman-Pillet, N.; Poirot, O.; Kellenberger, S.; Beckmann, J.S.; et al. Cell-permeable peptides induce dose- and length-dependent cytotoxic effects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 2222–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Waltman, A.; Han, H.; Collier, J.H. Switching the Immunogenicity of Peptide Assemblies Using Surface Properties. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9274–9286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsenmeier, M.; Faltova, L.; Morelli, C.; Capasso Palmiero, U.; Seiffert, C.; Küffner, A.M.; Pinotsi, D.; Zhou, J.; Mezzenga, R.; Arosio, P. The interface of condensates of the hnRNPA1 low-complexity domain promotes formation of amyloid fibrils. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 1340–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzu, K.; Lin, C.Y.; Yi, P.W.; Huang, C.H.; Masuhara, H.; Chatani, E. Spatiotemporal formation of a single liquid-like condensate and amyloid fibrils of α-synuclein by optical trapping at solution surface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2402162121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Zaidi, F.K.; Farag, M.; Ruff, K.M.; Mahendran, T.S.; Singh, A.; Gui, X.; Messing, J.; Taylor, J.P.; Banerjee, P.R.; et al. Tunable metastability of condensates reconciles their dual roles in amyloid fibril formation. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 2230–2245.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallbrecher, R.; Ackels, T.; Olea, R.A.; Klein, M.J.; Caillon, L.; Schiller, J.; Bovée-Geurts, P.H.; van Kuppevelt, T.H.; Ulrich, A.S.; Spehr, M.; et al. Membrane permeation of arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides independent of transmembrane potential as a function of lipid composition and membrane fluidity. J. Control. Release 2017, 256, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allolio, C.; Magarkar, A.; Jurkiewicz, P.; Baxová, K.; Javanainen, M.; Mason, P.E.; Šachl, R.; Cebecauer, M.; Hof, M.; Horinek, D.; et al. Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides induce membrane multilamellarity and subsequently enter via formation of a fusion pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11923–11928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swiecicki, J.; Bartsch, A.; Tailhades, J.; Di Pisa, M.; Heller, B.; Chassaing, G.; Mansuy, C.; Burlina, F.; Lavielle, S. The Efficacies of Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Accumulating in Large Unilamellar Vesicles Depend on their Ability To Form Inverted Micelles. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2014, 15, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batenburg, A.M.; Bougis, P.E.; Rochat, H.; Verkleij, A.J.; De Kruijff, B. Penetration of a cardiotoxin into cardiolipin model membranes and its implications on lipid organization. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 7101–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechara, C.; Sagan, S. Cell-penetrating peptides: 20 years later, where do we stand? FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I.D.; Jiao, C.-Y.; Aubry, S.; Aussedat, B.; Burlina, F.; Chassaing, G.; Sagan, S. Cell biology meets biophysics to unveil the different mechanisms of penetratin internalization in cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1798, 2231–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabulo, S.; Cardoso, A.L.; Mano, M.; De Lima, M.C.P. Cell-Penetrating Peptides—Mechanisms of Cellular Uptake and Generation of Delivery Systems. Pharmaceuticals 2010, 3, 961–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce, H.D.; Garcia, A.E.; Litt, J.; Kane, R.S.; Martin, P.; Enrique, N.; Rebolledo, A.; Milesi, V. Arginine-Rich Peptides Destabilize the Plasma Membrane, Consistent with a Pore Formation Translocation Mechanism of Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 1917–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, M.; Li, M. Direct Cytosolic Uptake of Cell Penetrating Peptides with Shortened Sidechains. Chembiochem 2025, 26, e202500391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Kang, Z.; Yu, B.; Chen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Q. All-Factor Analysis and Correlations on the Transmembrane Process for Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Langmuir 2019, 35, 9286–9296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yandek, L.E.; Pokorny, A.; Florén, A.; Knoelke, K.; Langel, Ü.; Almeida, P.F.F. Mechanism of the Cell-Penetrating Peptide Transportan 10 Permeation of Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 2434–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.F.; Pokorny, A. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial, Cytolytic, and Cell-Penetrating Peptides: From Kinetics to Thermodynamics. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 8083–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, S.F.; Bruhn, D.S.; Khandelia, H.; Cárdenas, M.; Nielsen, H.M. Shuffled lipidation pattern and degree of lipidation determines the membrane interaction behavior of a linear cationic membrane-active peptide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 578, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludtke, S.; He, K.; Huang, H. Membrane thinning caused by magainin 2. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 16764–16769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Shim, S.; Kim, D.; Won, S.; Joo, S.; Kim, S.; Jeon, N.L.; Yoon, S. β-Amyloid is transmitted via neuronal connections along axonal membranes. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 75, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, Q. Potential Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease: Modulating Tunneling Nanotube Dynamics Restores Mitochondrial Transport and Ameliorates Aβ-induced Toxicity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 775, 152157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardivel, M.; Bégard, S.; Bousset, L.; Dujardin, S.; Coens, A.; Melki, R.; Buée, L.; Colin, M. Tunneling nanotube (TNT)-mediated neuron-to neuron transfer of pathological Tau protein assemblies. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, X. Opportunities and Challenges in Tunneling Nanotubes Research: How Far from Clinical Application? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, G.; Kumbhar, R.; Blair, W.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M.; Mao, X. Emerging targets of α-synuclein spreading in α-synucleinopathies: A review of mechanistic pathways and interventions. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, R.; Sant’Anna, R.; da Fonseca, A.C.C.; Robbs, B.K.; Foguel, D.; Outeiro, T.F. Extracellular alpha-synuclein: Sensors, receptors, and responses. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 168, 105696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdinocci, D.; Kovarova, J.; Neuzil, J.; Pountney, D.L. Alpha-Synuclein Aggregates Associated with Mitochondria in Tunnelling Nanotubes. Neurotox. Res. 2021, 39, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukoreshtliev, N.V.; Wang, X.; Hodneland, E.; Gurke, S.; Barroso, J.F.V.; Gerdes, H.-H. Selective block of tunneling nanotube (TNT) formation inhibits intercellular organelle transfer between PC12 cells. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 1481–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, A.; Kashyap, R.; Sreedevi, P.; Jos, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Alex, A.; D’Souza, M.N.; Giridharan, M.; Muddashetty, R.; Manjithaya, R.; et al. Astroglia proliferate upon the biogenesis of tunneling nanotubes via α-synuclein dependent transient nuclear translocation of focal adhesion kinase. iScience 2024, 27, 110565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero Cervantes, D.; Zurzolo, C. Peering into tunneling nanotubes-The path forward. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e105789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delage, E.; Cervantes, D.C.; Pénard, E.; Schmitt, C.; Syan, S.; Disanza, A.; Scita, G.; Zurzolo, C. Differential identity of Filopodia and Tunneling Nanotubes revealed by the opposite functions of actin regulatory complexes. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 39632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, D. Invisible Bridges: Unveiling the Role and Prospects of Tunneling Nanotubes in Cancer Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 5413–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Gong, F.; Ma, P.; Qian, Y.; He, L.; Chen, L.; Qin, X.; Xu, L. Protein-activated and FRET enhanced excited-state intermolecular proton transfer fluorescent probes for high-resolution imaging of cilia and tunneling nanotubes in live cells. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 288, 122142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatulian, S.A.; Kandel, N. Membrane Pore Formation by Peptides Studied by Fluorescence Techniques. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2003, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kumari, S.; MG, S.; Mayor, S. Endocytosis unplugged: Multiple ways to enter the cell. Cell Res. 2010, 20, 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajoie, P.; Nabi, I.R. Regulation of raft-dependent endocytosis. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haucke, V.; Kozlov, M.M. Membrane remodeling in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs216812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, P.; Jana, N.R. Lipid-Raft-Mediated Direct Cytosolic Delivery of Polymer-Coated Soft Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 5323–5333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Rothberg, K.G.; Anderson, R.G. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J. Cell Biol. 1993, 123, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macia, E.; Ehrlich, M.; Massol, R.; Boucrot, E.; Brunner, C.; Kirchhausen, T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev. Cell 2006, 10, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futaki, S.; Nakase, I. Cell-Surface Interactions on Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides Allow for Multiplex Modes of Internalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2449–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arukuusk, P.; Pärnaste, L.; Margus, H.; Eriksson, N.K.J.; Vasconcelos, L.; Padari, K.; Pooga, M.; Langel, Ü. Differential Endosomal Pathways for Radically Modified Peptide Vectors. Bioconjug. Chem. 2013, 24, 1721–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saar, K.; Lindgren, M.; Hansen, M.; Eiríksdóttir, E.; Jiang, Y.; Rosenthal-Aizman, K.; Sassian, M.; Langel, Ü. Cell-penetrating peptides: A comparative membrane toxicity study. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 345, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfonzo-Méndez, M.A.; Sochacki, K.A.; Strub, M.-P.; Taraska, J.W. Dual clathrin and integrin signaling systems regulate growth factor receptor activation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Maloverjan, M.; Padari, K.; Abroi, A.; Rätsep, M.; Wärmländer, S.K.T.S.; Jarvet, J.; Gräslund, A.; Kisand, V.; Lõhmus, R.; et al. Choosing an Optimal Solvent Is Crucial for Obtaining Cell-Penetrating Peptide Nanoparticles with Desired Properties and High Activity in Nucleic Acid Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCher, J.C.; Nowak, S.J.; McMurry, J.L. Breaking in and busting out: Cell-penetrating peptides and the endosomal escape problem. Biomol. Concepts 2017, 8, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Gonçalves, N.P.; Vaegter, C.B.; Jensen, P.H.; Ferreira, N. The Prion-Like Spreading of Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease: Update on Models and Hypotheses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, K.; Ikenaka, K.; Kuma, A.; Doi, J.; Aguirre, C.; Wang, N.; Ajiki, T.; Choong, C.-J.; Kimura, Y.; Badawy, S.M.M.; et al. Lysophagy protects against propagation of α-synuclein aggregation through ruptured lysosomal vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2312306120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Tang, X. Tau internalization: A complex step in tau propagation. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.B.; Rajput, S.S.; Sharma, A.; Kataria, S.; Dutta, P.; Ananthanarayanan, V.; Nandi, A.; Patil, S.; Majumdar, A.; Subramanyam, D. Pathogenic Huntingtin aggregates alter actin organization and cellular stiffness resulting in stalled clathrin-mediated endocytosis. eLife 2024, 13, e98363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Ou, M.T.; Karuppagounder, S.S.; Kam, T.-I.; Yin, X.; Xiong, Y.; Ge, P.; Umanah, G.E.; Brahmachari, S.; Shin, J.-H.; et al. Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiated by binding lymphocyte-activation gene 3. Science 2016, 353, aah3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahic, M.; Bousset, L.; Bieri, G.; Melki, R.; Gitler, A.D. Axonal transport and secretion of fibrillar forms of α-synuclein, Aβ42 peptide and HTTExon 1. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desplats, P.; Lee, H.-J.; Bae, E.-J.; Patrick, C.; Rockenstein, E.; Crews, L.; Spencer, B.; Masliah, E.; Lee, S.-J. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13010–13015, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bres, E.E.; Faissner, A. Low Density Receptor-Related Protein 1 Interactions With the Extracellular Matrix: More Than Meets the Eye. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieri, G.; Gitler, A.D.; Brahic, M. Internalization, axonal transport and release of fibrillar forms of alpha-synuclein. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 109, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanekiyo, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C.-C.; Zhang, L.; Bu, G. Heparan Sulphate Proteoglycan and the Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 Constitute Major Pathways for Neuronal Amyloid-β Uptake. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Peng, C.; Wu, C.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.; Yu, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, M. Low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 1 mediates α-synuclein transmission from the striatum to the substantia nigra in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 2024, 21, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Jepson, T.; Shukla, S.; Maya-Romero, A.; Kampmann, M.; Xu, K.; Hurley, J.H. Tau fibrils induce nanoscale membrane damage and nucleate cytosolic tau at lysosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2315690121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, T.R.; Julian, R.R. Proteolysis of Amyloid β by Lysosomal Enzymes as a Function of Fibril Morphology. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 31520–31527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, S.L.Y.; Rennick, J.J.; Yuen, D.; Al-Wassiti, H.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Pouton, C.W. Unravelling cytosolic delivery of cell penetrating peptides with a quantitative endosomal escape assay. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klipp, A.; Burger, M.; Leroux, J.C. Get out or die trying: Peptide- and protein-based endosomal escape of RNA therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 200, 115047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönn, P.; Kacsinta, A.D.; Cui, X.S.; Hamil, A.S.; Kaulich, M.; Gogoi, K.; Dowdy, S.F. Enhancing Endosomal Escape for Intracellular Delivery of Macromolecular Biologic Therapeutics. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, B.C.; Fletcher, R.B.; Kilchrist, K.V.; Dailing, E.A.; Mukalel, A.J.; Colazo, J.M.; Oliver, M.; Cheung-Flynn, J.; Brophy, C.M.; Tierney, J.W.; et al. An anionic, endosome-escaping polymer to potentiate intracellular delivery of cationic peptides, biomacromolecules, and nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahni, A.; Qian, Z.; Pei, D. Cell-Penetrating Peptides Escape the Endosome by Inducing Vesicle Budding and Collapse. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 2485–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, N.; Gomez, G.A.; Howes, M.T.; Lo, H.P.; McMahon, K.-A.; Rae, J.A.; Schieber, N.L.; Hill, M.M.; Gaus, K.; Yap, A.S.; et al. Endocytic Crosstalk: Cavins, Caveolins, and Caveolae Regulate Clathrin-Independent Endocytosis. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovtun, O.; Tillu, V.A.; Ariotti, N.; Parton, R.G.; Collins, B.M. Cavin family proteins and the assembly of caveolae. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, J.; Zhao, J.; Miao, C.; Jiu, Y. Interactive mechanisms between caveolin-1 and actin filaments or vimentin intermediate filaments instruct cell mechanosensing and migration. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 14, mjac066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaeus, C.; Taraska, J.W. Energy and Dynamics of Caveolae Trafficking. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 614472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb-Abraham, E.; Shvartsman, D.E.; Donaldson, J.C.; Ehrlich, M.; Gutman, O.; Martin, G.S.; Henis, Y.I. Src-mediated caveolin-1 phosphorylation affects the targeting of active Src to specific membrane sites. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 3881–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimnicka, A.M.; Husain, Y.S.; Shajahan, A.N.; Sverdlov, M.; Chaga, O.; Chen, Z.; Toth, P.T.; Klomp, J.; Karginov, A.V.; Tiruppathi, C.; et al. Src-dependent phosphorylation of caveolin-1 Tyr-14 promotes swelling and release of caveolae. Mol. Biol. Cell 2016, 27, 2090–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, R.G. Caveolae: Structure, Function, and Relationship to Disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 34, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahammad, S.; Parmryd, I. Cholesterol Depletion Using Methyl-β-cyclodextrin. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1232, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, D.K.; Chaudhary, S.; Sunil, S. Investigation of endocytic pathways during entry of RNA viruses reveal novel host proteins as lipid raft dependent endocytosis mediators. Virology 2025, 608, 110531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Pei, X.; Cui, H.; Yu, Z.; Lee, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; He, H.; Yang, V.C. Cellular uptake mechanism and comparative in vitro cytotoxicity studies of monomeric LMWP-siRNA conjugate. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 63, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.N.; Mehta, R.R.; Yamada, T.; Lekmine, F.; Christov, K.; Chakrabarty, A.M.; Green, A.; Bratescu, L.; Shilkaitis, A.; Beattie, C.W.; et al. Noncationic Peptides Obtained from Azurin Preferentially Enter Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-L.; Liu, Y.-G.; Zhou, Y.-T.; Zhao, P.; Ren, H.; Xiao, M.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Qi, Z.-T. Endophilin-A2-mediated endocytic pathway is critical for enterovirus 71 entry into caco-2 cells. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parton, R.G.; Taraska, J.W.; Lundmark, R. Is endocytosis by caveolae dependent on dynamin? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 511–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niaz, S.; Forbes, B.; Raimi-Abraham, B.T. Exploiting Endocytosis for Non-Spherical Nanoparticle Cellular Uptake. Nanomanufacturing 2022, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fittipaldi, A.; Ferrari, A.; Zoppé, M.; Arcangeli, C.; Pellegrini, V.; Beltram, F.; Giacca, M. Cell Membrane Lipid Rafts Mediate Caveolar Endocytosis of HIV-1 Tat Fusion Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 34141–34149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säälik, P.; Padari, K.; Niinep, A.; Lorents, A.; Hansen, M.; Jokitalo, E.; Langel, Ü.; Pooga, M. Protein Delivery with Transportans Is Mediated by Caveolae Rather Than Flotillin-Dependent Pathways. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009, 20, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiman, K.-L.; Mäger, I.; Ezzat, K.; Margus, H.; Lehto, T.; Langel, K.; Kurrikoff, K.; Arukuusk, P.; Suhorutšenko, J.; Padari, K.; et al. PepFect14 Peptide Vector for Efficient Gene Delivery in Cell Cultures. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothberg, K.G. Caveolar targeting of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins. Methods Enzymol 1995, 250, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.D.; Zhuang, Y.; Ben, J.J.; Qian, L.L.; Huang, H.P.; Bai, H.; Sha, J.H.; He, Z.G.; Chen, Q. Caveolae-dependent endocytosis is required for class A macrophage scavenger receptor-mediated apoptosis in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 8231–8239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasannejad-Asl, B.; Pooresmaeil, F.; Takamoli, S.; Dabiri, M.; Bolhassani, A. Cell penetrating peptide: A potent delivery system in vaccine development. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1072685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belnoue, E.; Di Berardino-Besson, W.; Gaertner, H.; Carboni, S.; Dunand-Sauthier, I.; Cerini, F.; Suso-Inderberg, E.-M.; Wälchli, S.; König, S.; Salazar, A.M.; et al. Enhancing Antitumor Immune Responses by Optimized Combinations of Cell-penetrating Peptide-based Vaccines and Adjuvants. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, D.; Taha, M.; Tshuva, E.Y.; Reches, M. Tailoring Peptide Coacervates for Advanced Biotechnological Applications: Enhancing Control, Encapsulation, and Antioxidant Properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 31561–31574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Lykotrafitis, G.; Bao, G.; Suresh, S. Size-Dependent Endocytosis of Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shebanova, A.; Perrin, Q.M.; Zhu, K.; Gudlur, S.; Chen, Z.; Sun, Y.; Huang, C.; Lim, Z.W.; Mondarte, E.A.; Sun, R.; et al. Cellular Uptake of Phase-Separating Peptide Coacervates. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2402652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, A.J.; Allen, T.W. The role of tryptophan side chains in membrane protein anchoring and hydrophobic mismatch. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 864–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ounjian, J.; Bukiya, A.N.; Rosenhouse-Dantsker, A. Molecular Determinants of Cholesterol Binding to Soluble and Transmembrane Protein Domains. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1135, 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Yu, H.; Xu, X.; Yang, T.; Wei, Y.; Zan, R.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Shum, H.C.; Song, Y. AIEgen-Conjugated Phase-Separating Peptides Illuminate Intracellular RNA through Coacervation-Induced Emission. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 8195–8203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Fu, J.; Hou, S.; Zhang, J.; Gong, T.; Zhu, J.; Huang, S.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Duan, M.; et al. A coacervate-based redox-responsive cytoplasmic delivery system for antioxidant macromolecule to rescue sensorineural hearing loss. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbiv, Y.; Simhi-Haham, D.; Israeli, E.; Elhadi, S.A.; Grigoletto, J.; Sharon, R. Lysine residues at the first and second KTKEGV repeats mediate α-Synuclein binding to membrane phospholipids. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014, 70, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.-F.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Wang, H.-M.; Tian, L.-P.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.-Q.; Chen, S.-D. Curcumin Ameliorates the Neurodegenerative Pathology in A53T α-synuclein Cell Model of Parkinson’s Disease Through the Downregulation of mTOR/p70S6K Signaling and the Recovery of Macroautophagy. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashuel, H.A.; Petre, B.M.; Wall, J.; Simon, M.; Nowak, R.J.; Walz, T.; Lansbury, P.T. α-Synuclein, Especially the Parkinson’s Disease-associated Mutants, Forms Pore-like Annular and Tubular Protofibrils. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 322, 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, G.M.; Ceccato, N.; Conte, C. Synucleinopathies Take Their Toll: Are TLRs a Way to Go? Cells 2023, 12, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, L.A.; Khan, T.; El Khoury, J.B.; Pham, C.L.L.; Hatters, D.M.; Howlett, G.J.; Lopez, R.; O’Brien, K.D.; Moore, K.J. Fibrillar Amyloid Protein Present in Atheroma Activates CD36 Signal Transduction. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10643–10648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.P.; Walker, D.E.; Goldstein, J.M.; de Laat, R.; Banducci, K.; Caccavello, R.J.; Barbour, R.; Huang, J.; Kling, K.; Lee, M.; et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 Is the Dominant Pathological Modification of α-Synuclein in Familial and Sporadic Lewy Body Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29739–29752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, M.C.; Teasdale, R.D. Defining Macropinocytosis. Traffic 2009, 10, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, R.R. Macropinocytosis: Biology and mechanisms. Cells Dev. 2021, 168, 203713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, J.A.; Watts, C. Macropinocytosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1995, 5, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Harashima, H. Endocytosis of Gene Delivery Vectors: From Clathrin-dependent to Lipid Raft-mediated Endocytosis. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.P.; Gleeson, P.A. Macropinocytosis: An endocytic pathway for internalising large gulps. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2011, 89, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salloum, G.; Bresnick, A.R.; Backer, J.M. Macropinocytosis: Mechanisms and regulation. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 335–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, A.D.; Swanson, J.A. Cdc42, Rac1, and Rac2 Display Distinct Patterns of Activation during Phagocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 2004, 15, 3509–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltman, D.M.; Williams, T.D.; Bloomfield, G.; Chen, B.-C.; Betzig, E.; Insall, R.H.; Kay, R.R. A plasma membrane template for macropinocytic cups. eLife 2016, 5, e20085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwartkruis, F.J.T.; Burgering, B.M.T. Ras and macropinocytosis: Trick and treat. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrant, A.; Cardon, S.; Burlina, F.; Sagan, S. Membrane Crossing and Membranotropic Activity of Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Dangerous Liaisons? Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2968–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisguérin, P.; Deshayes, S.; Gait, M.J.; O’Donovan, L.; Godfrey, C.; Betts, C.A.; Wood, M.J.A.; Lebleu, B. Delivery of therapeutic oligonucleotides with cell penetrating peptides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, G.; Nakase, I.; Fukuda, Y.; Masuda, R.; Oishi, S.; Shimura, K.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Takatani-Nakase, T.; Langel, Ü.; Gräslund, A.; et al. CXCR4 Stimulates Macropinocytosis: Implications for Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides and HIV. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüşoğlu, İ.I.; Maloverjan, M.; Porosk, L.; Pooga, M. Supplementation with ions enhances the efficiency of nucleic acid delivery with cell-penetrating peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2024, 1868, 130719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, I.; Tadokoro, A.; Kawabata, N.; Takeuchi, T.; Katoh, H.; Hiramoto, K.; Negishi, M.; Nomizu, M.; Sugiura, Y.; Futaki, S. Interaction of Arginine-Rich Peptides with Membrane-Associated Proteoglycans Is Crucial for Induction of Actin Organization and Macropinocytosis. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakase, I.; Niwa, M.; Takeuchi, T.; Sonomura, K.; Kawabata, N.; Koike, Y.; Takehashi, M.; Tanaka, S.; Ueda, K.; Simpson, J.C.; et al. Cellular Uptake of Arginine-Rich Peptides: Roles for Macropinocytosis and Actin Rearrangement. Mol. Ther. 2004, 10, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richard, J.P.; Melikov, K.; Brooks, H.; Prevot, P.; Lebleu, B.; Chernomordik, L.V. Cellular Uptake of Unconjugated TAT Peptide Involves Clathrin-dependent Endocytosis and Heparan Sulfate Receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15300–15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomono, T.; Yagi, H.; Igi, R.; Tabaru, A.; Fujimoto, K.; Enomoto, K.; Ukawa, M.; Miyata, K.; Shigeno, K.; Sakuma, S. Mucosal absorption of antibody drugs enhanced by cell-penetrating peptides anchored to a platform of polysaccharides. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 647, 123499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, K.; Ishitobi, J.; Noguchi, K.; Kira, R.; Kitayama, Y.; Goto, Y.; Fujiwara, D.; Michigami, M.; Harada, A.; Takatani-Nakase, T.; et al. Extracellular Microvesicles Modified with Arginine-Rich Peptides for Active Macropinocytosis Induction and Delivery of Therapeutic Molecules. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 17069–17079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, I.; Illien, F.; Dókus, L.E.; Yousef, M.; Baranyai, Z.; Bősze, S.; Ise, S.; Kawano, K.; Sagan, S.; Futaki, S.; et al. Influence of the Dabcyl group on the cellular uptake of cationic peptides: Short oligoarginines as efficient cell-penetrating peptides. Amino Acids 2021, 53, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laniel, A.; Marouseau, É.; Nguyen, D.T.; Froehlich, U.; McCartney, C.; Boudreault, P.-L.; Lavoie, C. Characterization of PGua4, a Guanidinium-Rich Peptoid that Delivers IgGs to the Cytosol via Macropinocytosis. Mol. Pharm. 2023, 20, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivusalo, M.; Welch, C.; Hayashi, H.; Scott, C.C.; Kim, M.; Alexander, T.; Touret, N.; Hahn, K.M.; Grinstein, S. Amiloride inhibits macropinocytosis by lowering submembranous pH and preventing Rac1 and Cdc42 signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 188, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, N.; Johnson, M.T.; Swanson, J.A. A role for phosphoinositide 3-kinase in the completion of macropinocytosis and phagocytosis by macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 135, 1249–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Z.W.; Varma, V.B.; Ramanujan, R.V.; Miserez, A. Magnetically responsive peptide coacervates for dual hyperthermia and chemotherapy treatments of liver cancer. Acta Biomater. 2020, 110, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Hirose, H.; Sakamoto, K.; Hirai, Y.; Arafiles, J.V.V.; Akishiba, M.; Imanishi, M.; Futaki, S. Liquid Droplet Formation and Facile Cytosolic Translocation of IgG in the Presence of Attenuated Cationic Amphiphilic Lytic Peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 19804–19812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, B.B.; DeVos, S.L.; Kfoury, N.; Li, M.; Jacks, R.; Yanamandra, K.; Ouidja, M.O.; Brodsky, F.M.; Marasa, J.; Bagchi, D.P.; et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans mediate internalization and propagation of specific proteopathic seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E3138–E3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopschinski, B.E.; Holmes, B.B.; Miller, G.M.; Manon, V.A.; Vaquer-Alicea, J.; Prueitt, W.L.; Hsieh-Wilson, L.C.; Diamond, M.I. Specific glycosaminoglycan chain length and sulfation patterns are required for cell uptake of tau versus α-synuclein and β-amyloid aggregates. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10826–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeineddine, R.; Yerbury, J.J. The role of macropinocytosis in the propagation of protein aggregation associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandarini, E.; Tollapi, E.; Zanchi, M.; Depau, L.; Pini, A.; Brunetti, J.; Bracci, L.; Falciani, C. Endocytosis and Trafficking of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells Unraveled with a Polycationic Peptide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe-Querol, E.; Rosales, C. Phagocytosis: Our Current Understanding of a Universal Biological Process. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canton, J.; Fairn, G.D.; Jaumouillé, V. Editorial: Phagocytes in Immunity: Linking Material Internalization to Immune Responses and Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 772256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaumouillé, V.; Grinstein, S. Molecular Mechanisms of Phagosome Formation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harriff, M.J.; Purdy, G.E.; Lewinsohn, D.M. Escape from the Phagosome: The Explanation for MHC-I Processing of Mycobacterial Antigens? Front. Immunol. 2012, 3, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, L.; König, A.; Koenig, P.-A.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Westman, J.; Drummond, R.A.; Lionakis, M.S.; Groß, O.; Ruland, J.; Naglik, J.R.; et al. The fungal peptide toxin Candidalysin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and causes cytolysis in mononuclear phagocytes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P.K.; Lappalainen, P. Filopodia: Molecular architecture and cellular functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaumouillé, V.; Waterman, C.M. Physical Constraints and Forces Involved in Phagocytosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.A.; Neidt, E.M.; Cui, J.; Feiger, Z.; Skau, C.T.; Gardel, M.L.; Kozmin, S.A.; Kovar, D.R. Identification and Characterization of a Small Molecule Inhibitor of Formin-Mediated Actin Assembly. Chem. Biol. 2009, 16, 1158–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, X.; Nath, S.; Sun, H.; Tran, T.M.; Yang, L.; Mayor, S.; Miao, Y. Formin nanoclustering-mediated actin assembly during plant flagellin and DSF signaling. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetrick, B.; Han, M.S.; Helgeson, L.A.; Nolen, B.J. Small Molecules CK-666 and CK-869 Inhibit Actin-Related Protein 2/3 Complex by Blocking an Activating Conformational Change. Chem. Biol. 2013, 20, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenseler, W.; Zambon, F.; Lee, H.; Vowles, J.; Rinaldi, F.; Duggal, G.; Houlden, H.; Gwinn, K.; Wray, S.; Luk, K.C.; et al. Excess α-synuclein compromises phagocytosis in iPSC-derived macrophages. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenigsknecht, J.; Landreth, G. Microglial Phagocytosis of Fibrillar β-Amyloid through a β1 Integrin-Dependent Mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 9838–9846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Francis, N.L.; Song, S.; Kholodovych, V.; Calvelli, H.R.; Hoop, C.L.; Pang, Z.P.; Baum, J.; Uhrich, K.E.; Moghe, P.V. CD36-Binding Amphiphilic Nanoparticles for Attenuation of α-Synuclein-Induced Microglial Activation. Adv. Nanobiomed Res. 2022, 2, 2100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Paik, S.R.; Jou, I.; Park, S.M. Microglial phagocytosis is enhanced by monomeric α-synuclein, not aggregated α-synuclein: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. Glia 2008, 56, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Lee, S.-J.; Jou, I.; Joe, E.-H.; Park, S.M. FcγRIIB mediates the inhibitory effect of aggregated α-synuclein on microglial phagocytosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 83, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.-K.; Tao, K.-X.; Wang, X.-B.; Yao, X.-Y.; Pang, M.-Z.; Liu, J.-Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, C.-F. Role of α-synuclein in microglia: Autophagy and phagocytosis balance neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 72, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, T.; Foster, J.S.; Williams, A.D.; Williams, A.B.; Stroh, A.; Macy, S.; Wooliver, C.; Heidel, R.E.; Varanasi, S.K.; Ergen, E.N.; et al. Macrophage-Mediated Phagocytosis and Dissolution of Amyloid-Like Fibrils in Mice, Monitored by Optical Imaging. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvrčková, F.; Ghosh, R.; Kočová, H. Transmembrane formins as active cargoes of membrane trafficking. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 3668–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagho, M.D.; Schmidt, K.; Lambert, C.; Kaufmann, T.; Jia, L.; Faix, J.; Rottner, K.; Stadler, M.; Stradal, T.; Klahn, P. Comprehensive Cell Biological Investigation of Cytochalasin B Derivatives with Distinct Activities on the Actin Network. J. Nat. Prod. 2024, 87, 2421–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preta, G.; Cronin, J.G.; Sheldon, I.M. Dynasore-not just a dynamin inhibitor. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Wan, Q.; Glebov, O.O. Temperature-induced membrane trafficking drives antibody delivery to the brain. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 189, 118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Sayers, E.J.; Watson, P.; Jones, A.T. Contrasting roles for actin in the cellular uptake of cell penetrating peptide conjugates. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Kuwata, K.; Chiba, J.; Hatanaka, Y.; Nakase, I.; Futaki, S. Syndecan-4 Is a Receptor for Clathrin-Mediated Endocytosis of Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehto, T.; Isakannu, M.; Sork, H.; Lorents, A.; Bazaz, S.; Wiklander, O.P.B.; Andaloussi, S.E.; Lehto, T. Amphipathic Octenyl-Alanine Modified Peptides Mediate Effective siRNA Delivery. J. Pept. Sci. 2025, 31, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Tostanoski, L.H.; Jewell, C.M. Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Assembled Entirely from Immune Signals on Gold Nanoparticle Templates Promote Antigen-Specific T Cell Response. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 6465–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chedid, J.; Labrador-Garrido, A.; Zhong, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Perera, G.; Kim, W.S.; Halliday, G.M.; Dzamko, N. A small molecule toll-like receptor antagonist rescues α-synuclein fibril pathology. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarnataro, D.; Caputo, A.; Casanova, P.; Puri, C.; Paladino, S.; Tivodar, S.S.; Campana, V.; Tacchetti, C.; Zurzolo, C. Lipid Rafts and Clathrin Cooperate in the Internalization of PrPC in Epithelial FRT Cells. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phase State | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CPPs | Coacervates | Fibrils | |

| Size | <5 nm | 300 nm–1 µm | length: up to several μm width: 2–7 nm (protofilaments); 7–20 nm (filaments) |

| Charge and/or sequence patterns | Positive or weakly positive charge | Charge blockiness; repeated sequences | The presence of amyloidogenic patterns (alternating blocks of polar and hydrophobic residues) |

| Hydrophobicity | Amphipathic or hydrophobic | Hydrophobic or amphipathic | Amphipathic or hydrophobic |

| Secondary structure | Disordered or α-helical | Disordered | Cross-β structure |

| Immunogenicity | Non-immunogenic | Non-immunogenic | Can be immunogenic |

| Toxicity | Non-toxic | Non-toxic | Can be toxic |

| The most common entry pathway without cargo | Direct transport | Cholesterol-dependent endocytosis/ phagocytosis-like mechanism | HSPG-dependent endocytosis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vedekhina, T.; Pavlova, I.; Svetlova, J.; Khomyakova, J.; Varizhuk, A. Intracellular Transport of Monomeric Peptides, (Poly)Peptide-Based Coacervates and Fibrils: Mechanisms and Prospects for Drug Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211015

Vedekhina T, Pavlova I, Svetlova J, Khomyakova J, Varizhuk A. Intracellular Transport of Monomeric Peptides, (Poly)Peptide-Based Coacervates and Fibrils: Mechanisms and Prospects for Drug Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211015

Chicago/Turabian StyleVedekhina, Tatiana, Iuliia Pavlova, Julia Svetlova, Julia Khomyakova, and Anna Varizhuk. 2025. "Intracellular Transport of Monomeric Peptides, (Poly)Peptide-Based Coacervates and Fibrils: Mechanisms and Prospects for Drug Delivery" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211015

APA StyleVedekhina, T., Pavlova, I., Svetlova, J., Khomyakova, J., & Varizhuk, A. (2025). Intracellular Transport of Monomeric Peptides, (Poly)Peptide-Based Coacervates and Fibrils: Mechanisms and Prospects for Drug Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211015