Screening and Identification of Reference Genes Under Different Conditions and Growth Stages of Lyophyllum decastes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

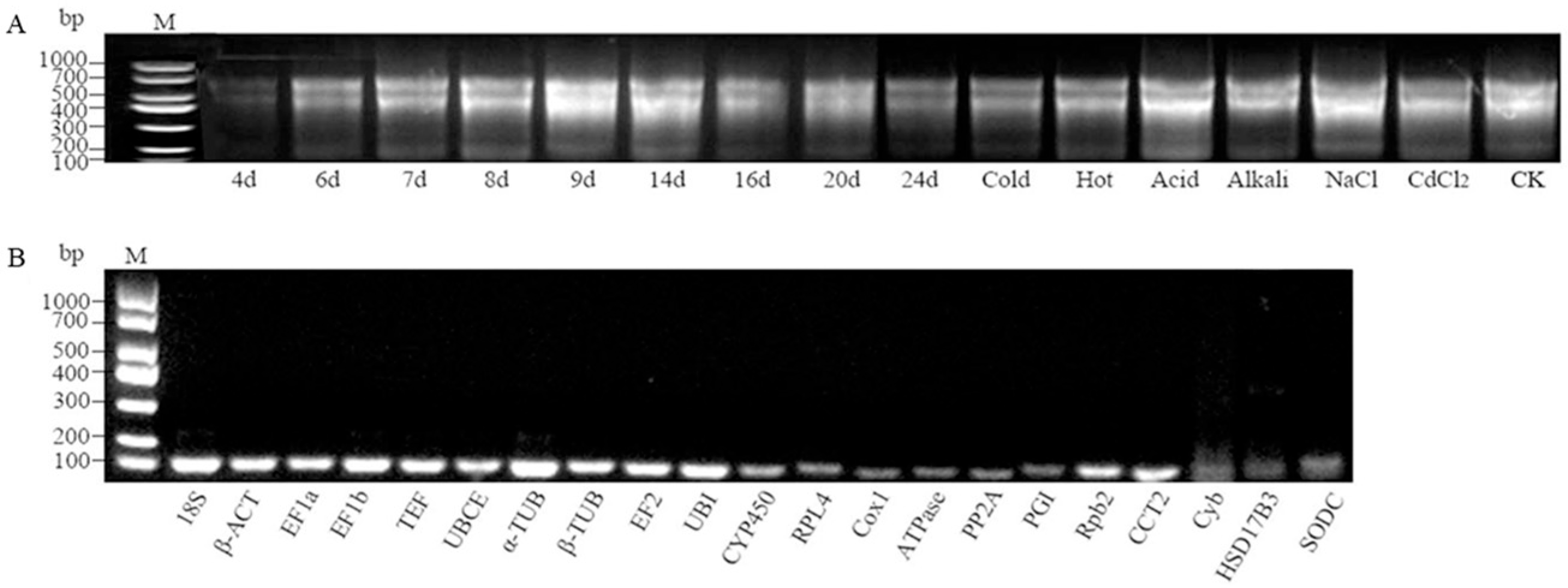

2.1. Total RNA Quality Assessment

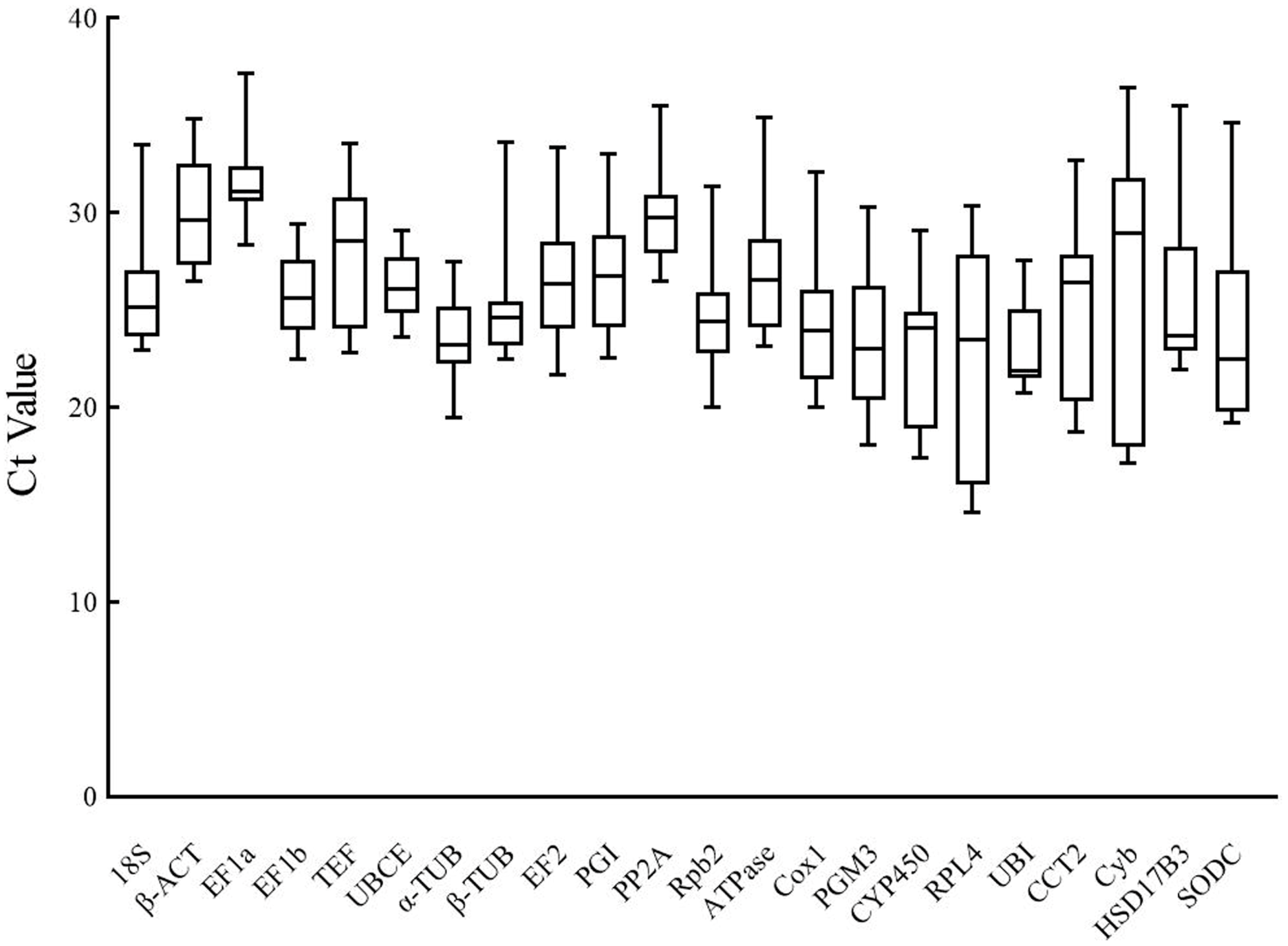

2.2. Analysis of Ct Values of Candidate Reference Genes

2.3. Analysis of the Expression Stability of Candidate Genes

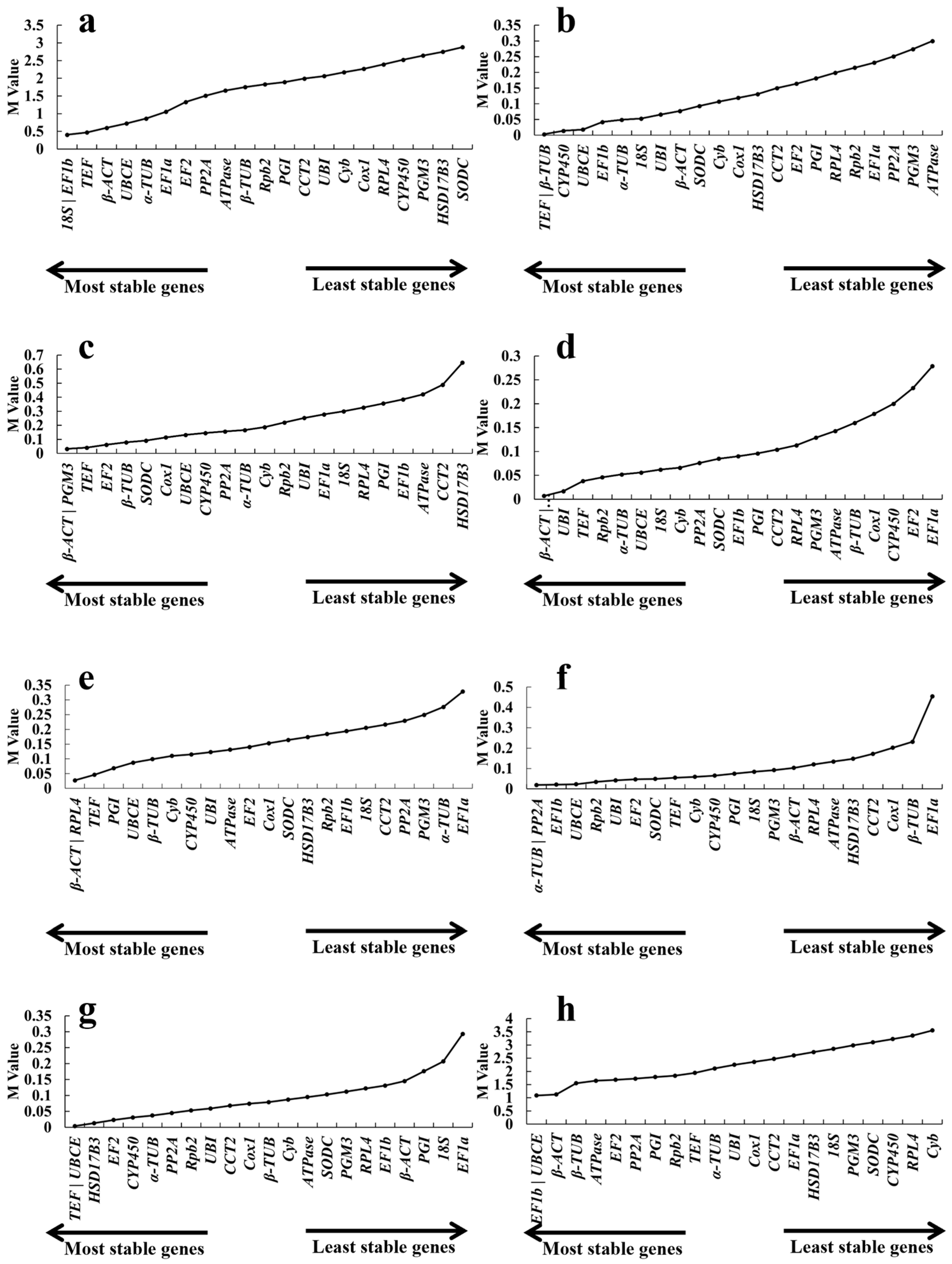

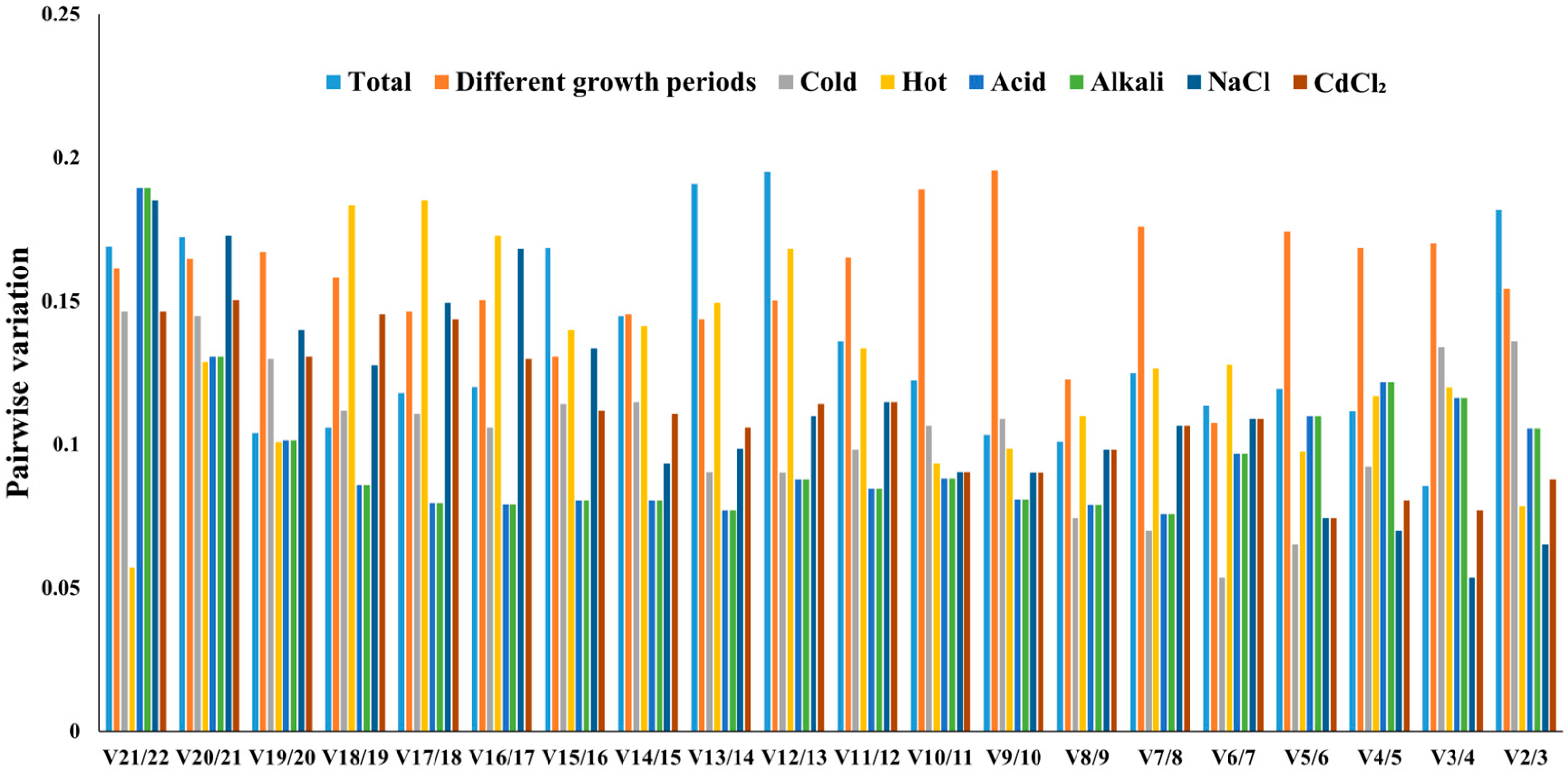

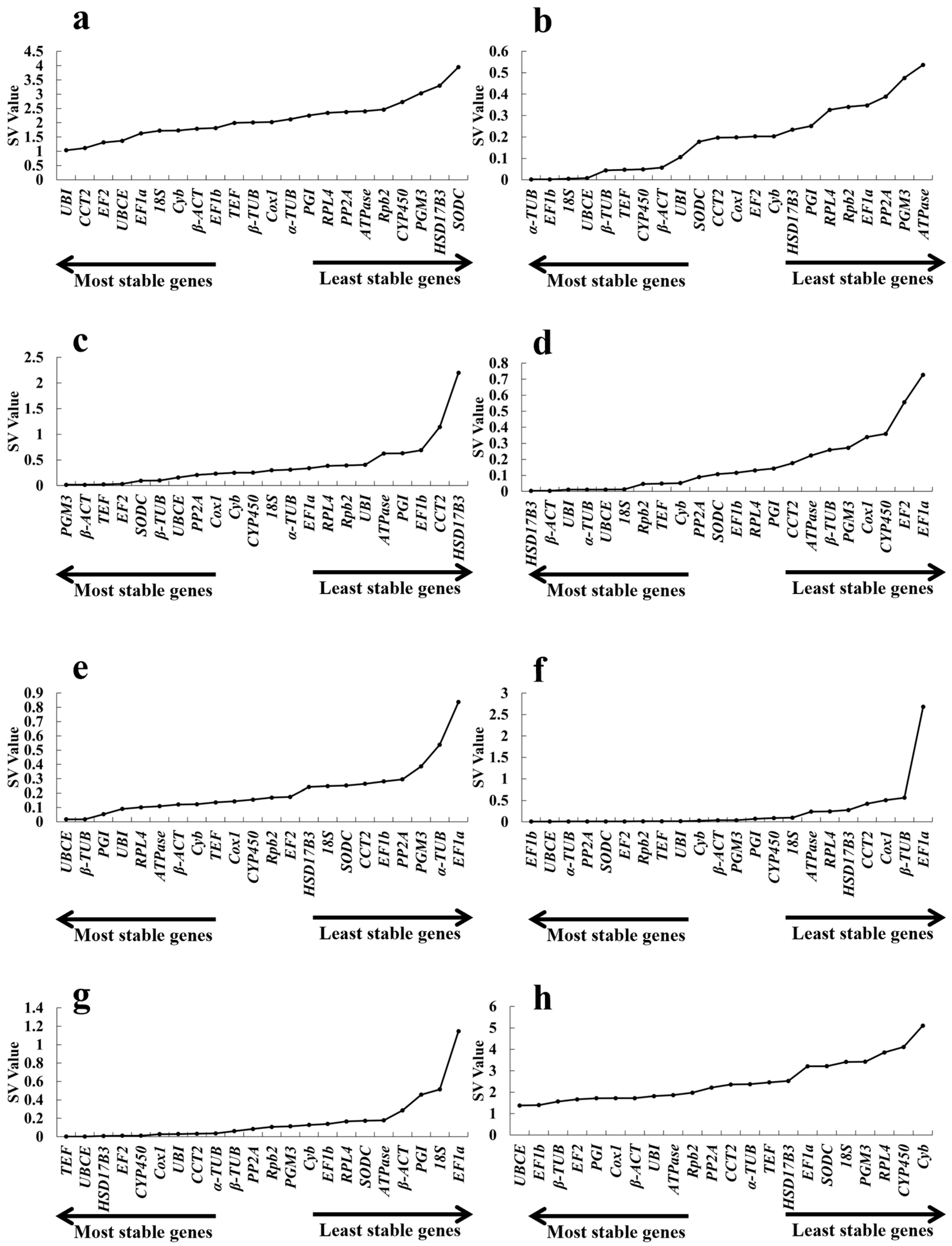

2.3.1. geNorm Analysis

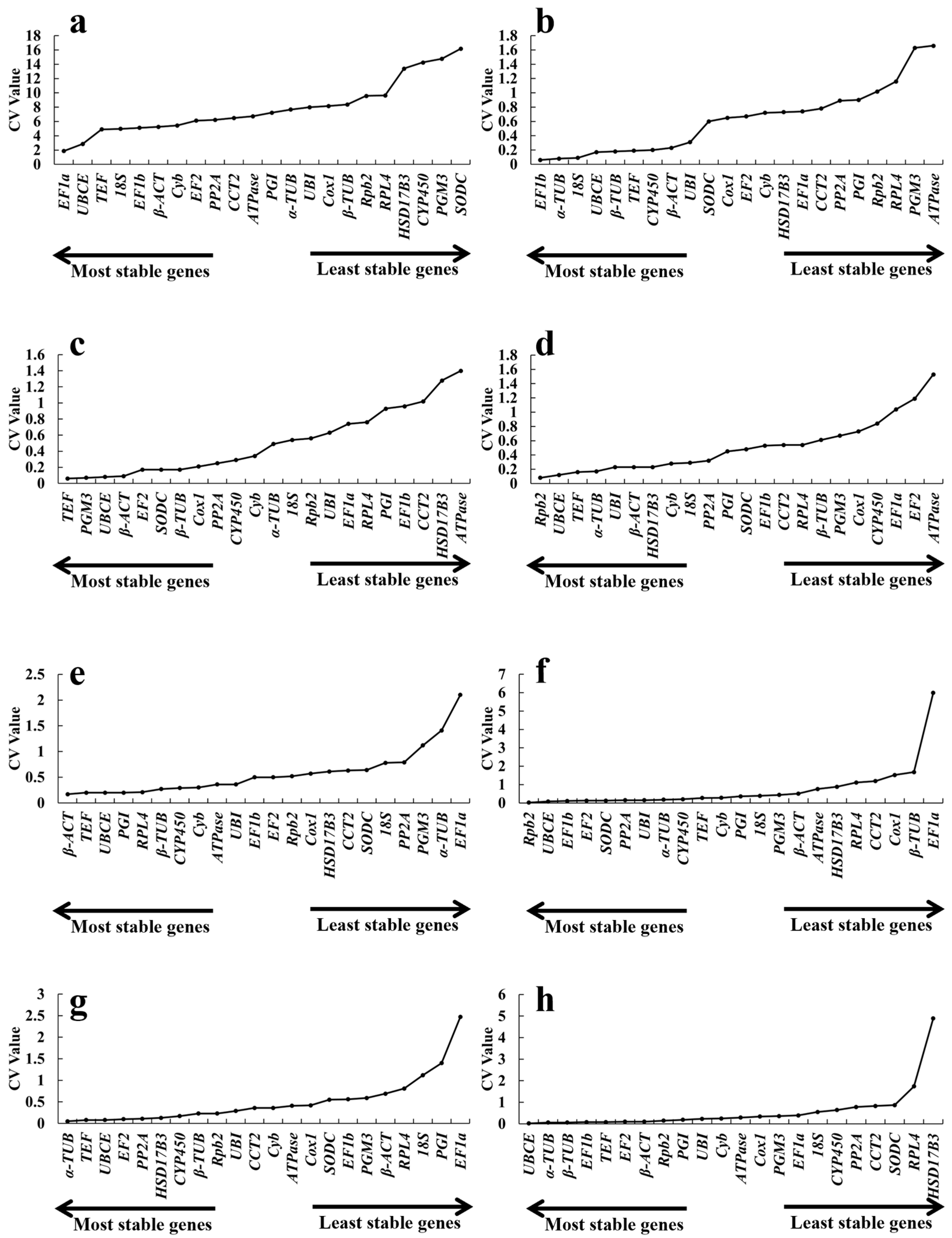

2.3.2. NormFinder Analysis

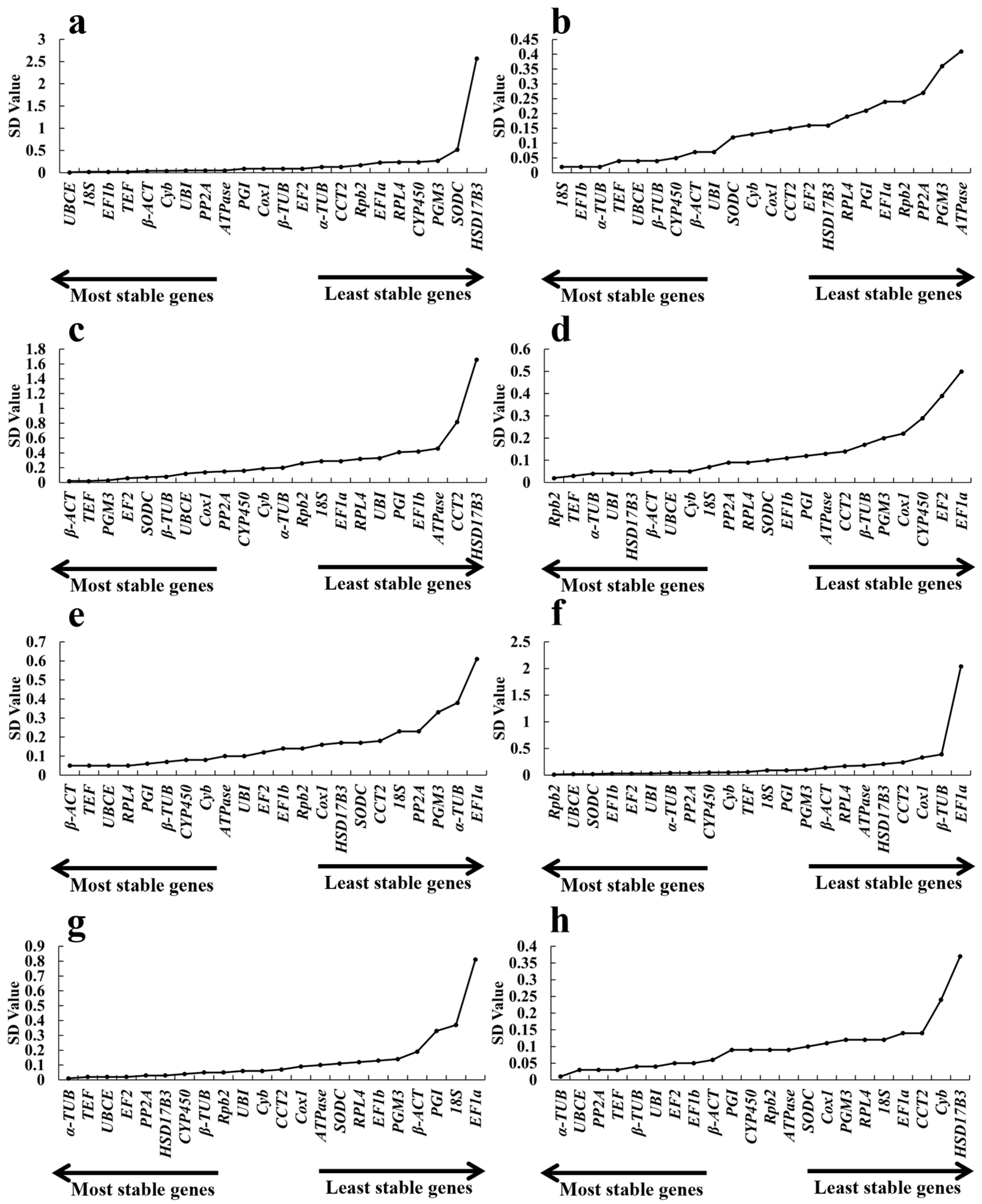

2.3.3. BestKeeper Analysis

2.3.4. Comprehensive Stability Analysis of the Reference Genes

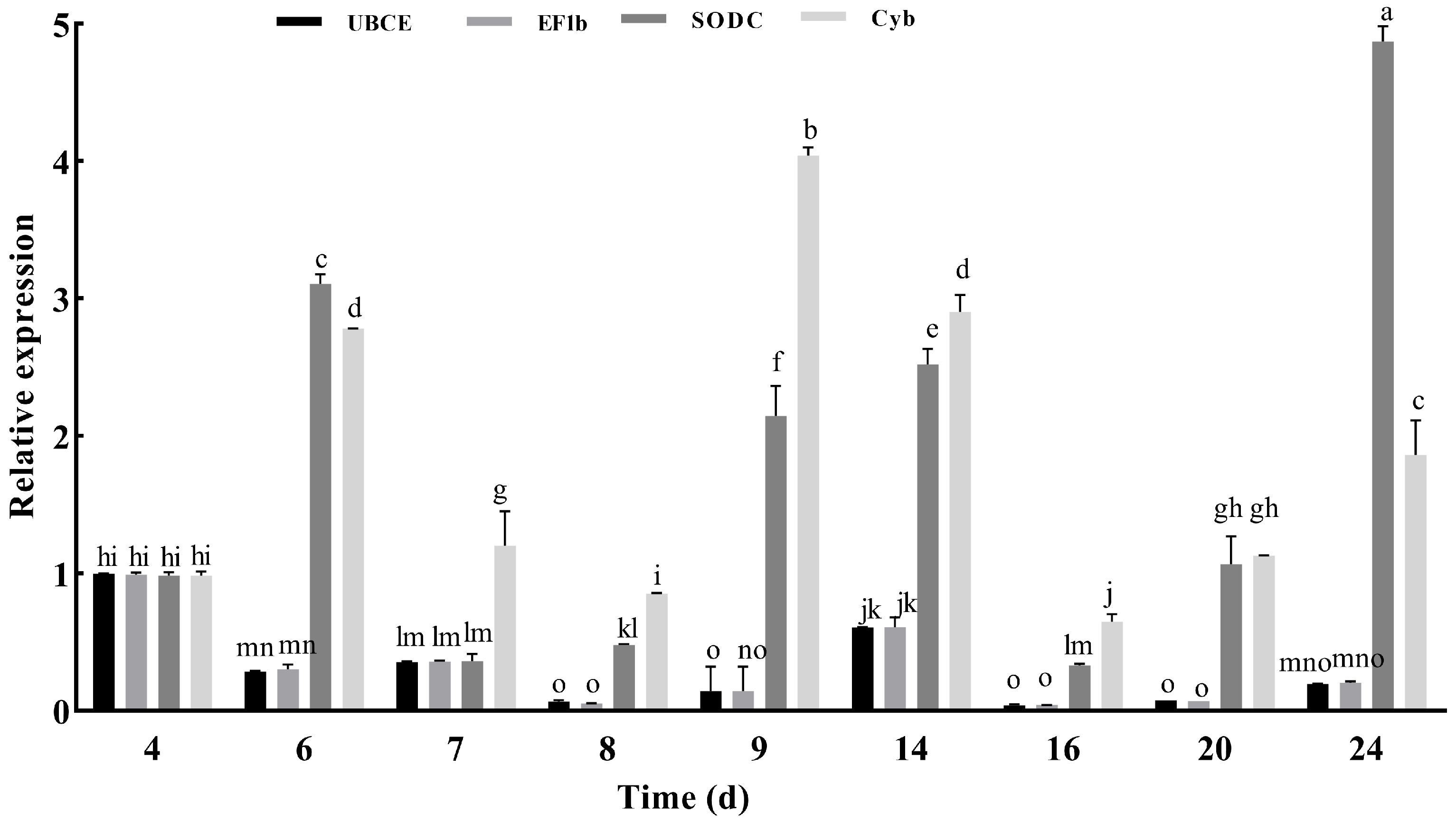

2.4. Verification of Reference Gene Stability

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Preparation

4.2. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

4.3. Selection of Reference Candidate Genes and Primer Design

4.4. Fluorescence Quantitative PCR

4.5. Data Analysis

4.6. Experimental Validation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Wen, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.; Pei, Y.; Wei, L.; Lu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, S. Research progress of Lyophyllum decastes. Edible Fungi China 2022, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Wei, C.; Feng, B.; Ren, A.; Hu, J.; Kong, X.; Liu, H. An overview of the research on Lyophyllum decastes. Edible Fungi China 2024, 46, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.J.; Xiao, S.J.; Xie, Y.H.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.R.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yang, T.; Zhou, T.Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; et al. Structural characterization and immune activity evaluation of a polysaccharide from Lyophyllum decastes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.M. Nutrition ingredient analysis and evaluation of Lyophyllum decastes fruit body. Mycosystema 2008, 27, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zheng, H.; Ben, W.; Ma, S. Industrial cultivation of Lyophyllum decastes. Acta Edulis Fungi 2008, 15, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Research progress on reference gene selection in real-time quantitative PCR of tomatoes. North. Hortic. 2015, 23, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Zang, X.; Zhang, P.; Sun, J.; Shi, Q.; Chang, S.; Ren, P.; Li, Z.; Meng, L. Screening of the candidate metabolite to evaluate the mycelium physiological maturation of Lyophyllum decastes based on metabolome and transcriptome analysis. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, W.; Qiu, T.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Cui, H.; Guo, L.; Yu, H.; Yu, H. Complete genome sequences and comparative secretomic analysis for the industrially cultivated edible mushroom Lyophyllum decastes reveals insights on evolution and lignocellulose degradation potential. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1137162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Ding, L.; Niu, X.; Shan, H.; Song, L.; Xi, Y.; Feng, J.; Wei, S.; Liang, Q. Comparative transcriptome analysis on candidate genes associated with fruiting body growth and development in Lyophyllum decastes. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qin, Y.; Kong, Y.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Liang, Y.; Xu, J. Optimization of protoplast preparation conditions in Lyophyllum decastes and transcriptomic analysis throughout the process. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jozefczuk, J.; Adjaye, J. Quantitative real-time PCR-based analysis of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 2011, 500, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandita, S.; Alam, H.; Shivhare, R.; Singh, M.; Singh, S.; Mishra, G.; Verma, P.C. Selection and validation of reference genes for quantitative expression analysis of regeneration-related genes in Cheilomenes sexmaculata by real-time qRT-PCR. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Yang, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, D.; Xia, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, C. Selection and verification of reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR in endangered mangrove species Acanthus ebracteatus under different abiotic stress conditions. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 204, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marabita, F.; de Candia, P.; Torri, A.; Tegnér, J.; Abrignani, S.; Rossi, R.L. Normalization of circulating microRNA expression data obtained by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Briefings Bioinform. 2016, 17, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, B.; Rapacz, M. Reference genes in real-time PCR. J. Appl. Genet. 2013, 54, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaan, D.; Vandesompele, J.; Hellemans, J. How to do successful gene expression analysis using real-time PCR. Methods 2009, 50, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shen, Y.; Feng, W.; Jin, Q.; Song, T.; Fan, L.; Cai, W. Screening of internal reference gene of Agaricus bisporus. Acta Agric. Zhejiangensis 2019, 31, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, L.; Shan, T.; Xing, Y.; Guo, S. Selection of reference genes for real-time quantitative PCR of Armillaria mellea. Microbiol. China 2022, 49, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.-H.; Wang, B.; Li, X.-L.; Tan, W.; Gan, B.-C.; Peng, W.-H. Validation of reference genes for quantitative gene expression analysis in Auricularia cornea. J. Microbiol. Methods 2019, 163, 105658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, J.; Ji, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Song, J.; Chen, S. Genome-wide selection of superior reference genes for expression studies in Ganoderma lucidum. Gene 2015, 574, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Shao, Y.; Chen, H.; Qi, Y.; Wang, F.; Wen, Q.; Shen, J. The screening of reference genes in RT-qPCR under heat stress of Pleurotus ostreatus. J. Fungi Res. 2023, 21, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Xia, Y.; Xie, F.; Vestine, U.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, G. Screening of the reference genes for qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Mycosystema 2021, 40, 1712–17122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Selection of Reference Gene for qRT–PCR in Wolfiporia cocos. Master’s Thesis, Wuhan University of Technology, Wuhan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Yao, F.; Sun, W.; Fang, M.; Wu, C. Screening of reference genes for qRT-PCR amplification in Auricularia heimuer. Mycosystema 2020, 39, 1510–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yuan, X.; Song, L.; Chang, M.; Liu, J.; Deng, B.; Meng, J. Screening of reference genes for real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR of Flammulina filiformis. Acta Edulis Fungi 2021, 28, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Guo, X.; Wang, S. Selection and evaluation of reference genes for qRT-PCR in Inonotus obliquus. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1500043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Gong, Y.; Bian, Y.; Zhou, Y. Selection and validation of reference genes for qRT-PCR in Lentinula edodes under different experimental conditions. Genes 2019, 10, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, X.; Cai, Q.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Mo, M. Screening of the internal reference genes of Tricholoma giganteum. Acta Edulis Fungi 2017, 24, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Cai, Y.; Lan, A.; Bian, Y. Validation of internal control genes for quantitative real-time PCR gene expression analysis in Morchella. Molecules 2018, 23, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhou, C.; Wan, J.; Guo, T.; Ji, G.; Luo, S.; Ji, K.; Cao, Y.; Tan, Q.; Bao, D.; et al. Selection and validation of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT–qPCR normalization of Phlebopus portentosus gene expression under different conditions. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Wang, J. Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR of lignification related genes in postharvest Pleurotus eryngii. J. Northwest A&F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2015, 43, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarivi, O.; Cesare, P.; Ragnelli, A.M.; Aimola, P.; Leonardi, M.; Bonfigli, A.; Colafarina, S.; Poma, A.M.; Miranda, M.; Pacioni, G. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in périgord black truffle (Tuber melanosporum) developmental stages. Phytochemistry 2015, 116, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Gao, Y.; Wáng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wāng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Bao, D.; Xu, J.; Bian, X. Selection and evaluation of appropriate reference genes for RT-qPCR normalization of Volvariella volvacea gene expression under different conditions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 6125706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Li, H.; Lan, Y.; Zang, X.; Lin, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ren, P.; Meng, L. Screening and validation of reference genes in Lyophyllum decastes by qRT-PCR. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 32, 2915–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Liang, Q.; Lai, Z.; Cui, H.; Xu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, Y. Systematic selection of suitable reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR normalization studies of gene expression in Lutjanus erythropterus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Ørntoft, T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. Reffinder: A web-based tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Spiegelaere, W.; Dern-Wieloch, J.; Weigel, R.; Schumacher, V.; Schorle, H.; Nettersheim, D.; Bergmann, M.; Brehm, R.; Kliesch, S.; Vandekerckhove, L. Reference gene validation for RT-qPCR, a note on different available software packages. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0122515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Yin, T. A selection of reliable reference genes for gene expression analysis in the female and male flowers of Salix suchowensis. Plants 2022, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Miao, R.; Zhao, X.; Ni, Y.; Li, W.; Feng, R.; Yang, D. Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Hymenopellis radicata under abiotic stress. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 1567–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, F.; Wu, K.; Wang, L.; Liang, L. Fluorescence quantitative PCR internal reference gene screening and determination of gene expression levels related to polysaccharide anabolism in Tricholoma alba. Acta Edulis Fungi 2021, 28, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Luo, J.; Xu, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, T.; Han, C.; Chen, Y.; Kong, L. Selection of reference genes for gene expression normalization in Peucedanum praeruptorum dunn under abiotic stresses, hormone treatments and different tissues. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, G.L.; Xu, Z.S.; Xiong, A.S. Selection of suitable reference genes for qPCR normalization under abiotic stresses and hormone stimuli in carrot leaves. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Tian, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, F.; Jiang, M.; Wen, H. Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of gene expression in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Gene 2013, 527, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Ren, J.; Hong, T.; Dong, Z.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, C.; Hu, Z. Identification of stable reference genes for QPCR analysis of gene expression in Oocystis borgei under various abiotic conditions. Algal Res. 2025, 86, 103899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, L.F.; Piovezani, A.R.; Ivanov, D.A.; Yoshida, L.; Segal, F.E.I.; Kato, M.J. Selection and validation of reference genes for measuring gene expression in Piper species at different life stages using RT-qPCR analysis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 171, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuschewski, K.; Hauser, H.P.; Treier, M.; Jentsch, S. Identification of a novel family of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes with distinct amino-terminal extensions. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 2789–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Bao, D.; Zhu, Q.; Tan, Q. A newly discovered ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 correlated with the cryogenic autolysis of Volvariella volvacea. Gene 2016, 583, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.F.; Feng, L.; Hou, Y.J.; Liu, W. The expression, purification and crystallization of a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 from Agrocybe aegerita underscore the impact of his-tag location on recombinant protein properties. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2013, 69, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.S.; Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Reddy, P.S.; Cindhuri, K.S.; Sivaji Ganesh, A.; Sharma, K.K. Identification and validation of reference genes and their impact on normalized gene expression studies across cultivated and wild Cicer species. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Ren, A.; Shi, L.; Jiang, A.; Yu, H.; Zhao, M. Identification of reference genes and analysis of heat shock protein gene expression in Lingzhi or Reishi medicinal mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum, after exposure to heat stress. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2017, 19, 1029–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M. Selection of reliable reference genes for RT-qPCR during methyl jasmonate, salicylic acid and hydrogen peroxide treatments in Ganoderma lucidum. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong-Duk, Y.; Chil, H.Y.; Sa-Ouk, K. Role of laccase in lignin degradation by white-rot fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1995, 132, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, M.; Song, X.; Yu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Y. Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR of mycelia from Lentinula edodes under high-temperature stress. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1670328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ge, W.; Buswell, J. Molecular cloning of a new laccase from the edible straw mushroom Volvariella volvacea: Possible involvement in fruit body development. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 230, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wu, G.; Lian, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, W.; Yang, Z.; Miao, J.; Chen, B.; Xie, B. Cloning and expression analysis of Vvlcc3, a novel and functional laccase gene possibly involved in stipe elongation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 28498–28509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.; Torres, G.; Lin, X. Laccases involved in 1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene melanin biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus are regulated by developmental factors and copper homeostasis. Eukaryot. Cell 2013, 12, 1641–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.F.; Wheeler, M.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. A developmentally regulated gene cluster involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6469–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, W.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W. The development and nutritional quality of Lyophyllum decastes affected by monochromatic or mixed light provided by light-emitting diode. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1404138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Tichopad, A.; Prgomet, C.; Neuvians, T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: Bestkeeper–Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Different Growth Periods Ranking | Cold Ranking | Hot Ranking | Acid Ranking | Alkali Ranking | NaCl Ranking | CdCl2 Ranking | Total Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBCE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| EF1b | 3 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| β-TUB | 12 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 21 | 3 | 3 |

| β-ACT | 9 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 7 | 4 |

| EF2 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 20 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 5 |

| PGI | 15 | 16 | 8 | 12 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| ATPase | 14 | 20 | 22 | 18 | 8 | 17 | 17 | 7 |

| PP2A | 13 | 7 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| EF1a | 4 | 21 | 19 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 9 |

| α-TUB | 11 | 4 | 12 | 1 | 21 | 3 | 16 | 10 |

| UBI | 6 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 11 |

| Rpb2 | 17 | 11 | 7 | 16 | 13 | 4 | 12 | 12 |

| Cox1 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 9 | 12 | 20 | 18 | 13 |

| TEF | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 14 |

| CCT2 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 10 | 18 | 19 | 13 | 15 |

| 18S | 2 | 10 | 9 | 13 | 17 | 13 | 21 | 16 |

| HSD17B3 | 21 | 18 | 20 | 15 | 14 | 18 | 22 | 17 |

| PGM3 | 20 | 19 | 17 | 14 | 20 | 14 | 14 | 18 |

| SODC | 22 | 22 | 14 | 11 | 15 | 6 | 19 | 19 |

| CYP450 | 19 | 9 | 6 | 21 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 20 |

| RPL4 | 18 | 12 | 15 | 17 | 3 | 16 | 10 | 21 |

| Cyb | 10 | 14 | 21 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 22 |

| Primer Name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Length of Product (bp) | Tm/°C |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18S-F | TATTATGGCGACACCGAGGC | 191 | 57.45 |

| 18S-R | CCCAGCCCAAATGTAACCCT | 57.45 | |

| EF1a-F | CGTGGTAACGTCTGTTCCGA | 137 | 57.45 |

| EF1a-R | TGAGCGGTGTGACAATCCAA | 59.5 | |

| β-ACT-F | CTTCCCATTCCCCTGACCTG | 126 | 59.5 |

| β-ACT-R | GCGCTTCAAACCCGACTAAG | 57.45 | |

| UBCE-F | GCTAGATCGTTTGTCGCAGC | 112 | 57.45 |

| UBCE-R | TGTGACTGCAAGAGTCCGTC | 55.40 | |

| TEF-F | GTCCAGGCCGTTGAACAAAC | 107 | 55.40 |

| TEF-R | AAGGGCGAAGATAGCGATGG | 57.45 | |

| EF1b-F | ACCGCTTTTTGCCGAAATCC | 185 | 57.45 |

| EF1b-R | TCACCATGAAACTGCCCTCC | 55.40 | |

| α-TUB-F | GACCGAGACCTTATGGAGCG | 159 | 55.40 |

| α-TUB-R | GAGGTCTGTGTCGTGTCCTG | 57.45 | |

| β-TUB-F | CGAAAGCTTTAGGAAGTGCCG | 99 | 59.50 |

| β-TUB-R | CCGGATGAATGGAAGAGGGG | 57.40 | |

| UBI-F | CTGCGTAACACGGACGAGAT | 116 | 57.45 |

| UBI-R | AGCACTTGTGCGATCTGAGG | 57.45 | |

| CYP450-F | ATCCGCTTATCGGACACCTC | 124 | 57.45 |

| CYP450-R | GTGGAGCGCATGAATCTCCT | 57.45 | |

| RPL4-F | CATGTTCGCTCCCACCAAGA | 156 | 59.5 |

| RPL4-R | AGGGGAACCTCCTCGATCTC | 59.5 | |

| EF2-F | CTGTGCAGAAGAGAACATGCG | 103 | 57.45 |

| EF2-R | CTATAGGACTCGGTGGGCAAA | 57.45 | |

| PGM3-F | TCATGATTGCCAGCGAACCT | 114 | 55.40 |

| PGM3-R | CGATAATCGGGACCTGGAGC | 55.40 | |

| CCT2-F | GTGAAGCTCGGACACTGTGA | 166 | 57.45 |

| CCT2-R | CAGAAAGCGCATCGTGTAGC | 57.45 | |

| Cox1-F | TGGGGTGGTTCTGTCGATTG | 181 | 55.40 |

| Cox1-R | CGCGTGGAATGAAAGTAGCG | 55.40 | |

| Cyb-F | GGACCATCCAGACCGTGAAG | 170 | 57.45 |

| Cyb-R | GTAGAGGACAACACCGAGGC | 59.50 | |

| ATPase-F | CTGCAGGCCATTTCGTATGC | 155 | 57.40 |

| ATPase-R | TCGCTACTCGGATTTCTCGC | 57.45 | |

| HSD17B3-F | TTCCAGCATCGTTGCAGTCT | 178 | 55.40 |

| HSD17B3-R | GTTGGCGATAGCAAAGCTCG | 55.40 | |

| PGI-F | TGATCGAGGTCGACTGAGGT | 147 | 57.45 |

| PGI-R | GACCATGACCGCACTCTTCA | 57.45 | |

| PP2A-F | TGCGATAGCCATTGTGGGTT | 148 | 55.40 |

| PP2A-R | GAGACGATGGCACGAGTAGG | 55.40 | |

| Rpb2-F | GAAGGCGTACTTCGTCCACA | 106 | 57.45 |

| Rpb2-R | CACTCTGGAGATCCCTTGGC | 59.50 | |

| SODC-F | CATGACCGAAACATCGACGC | 113 | 57.40 |

| SODC-R | ACAATTCGCAACCCATTGCC | 57.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hui, Y.-Q.; Yang, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Zhu, C.-Z.; Xi, L.-P.; Song, C.-Y.; Li, Z.-P.; Li, E.-X.; Li, S.-H.; Liu, Y.-N.; et al. Screening and Identification of Reference Genes Under Different Conditions and Growth Stages of Lyophyllum decastes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211004

Hui Y-Q, Yang H-L, Zhang Y-Q, Zhu C-Z, Xi L-P, Song C-Y, Li Z-P, Li E-X, Li S-H, Liu Y-N, et al. Screening and Identification of Reference Genes Under Different Conditions and Growth Stages of Lyophyllum decastes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211004

Chicago/Turabian StyleHui, Yun-Qi, Huan-Ling Yang, Yu-Qing Zhang, Chen-Zhao Zhu, Li-Ping Xi, Chun-Yan Song, Zheng-Peng Li, E-Xian Li, Shu-Hong Li, Yong-Nan Liu, and et al. 2025. "Screening and Identification of Reference Genes Under Different Conditions and Growth Stages of Lyophyllum decastes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211004

APA StyleHui, Y.-Q., Yang, H.-L., Zhang, Y.-Q., Zhu, C.-Z., Xi, L.-P., Song, C.-Y., Li, Z.-P., Li, E.-X., Li, S.-H., Liu, Y.-N., & Yang, R.-H. (2025). Screening and Identification of Reference Genes Under Different Conditions and Growth Stages of Lyophyllum decastes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211004