Polyphenolic Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Polyphenolic Compounds—Characteristics and Presence in Food

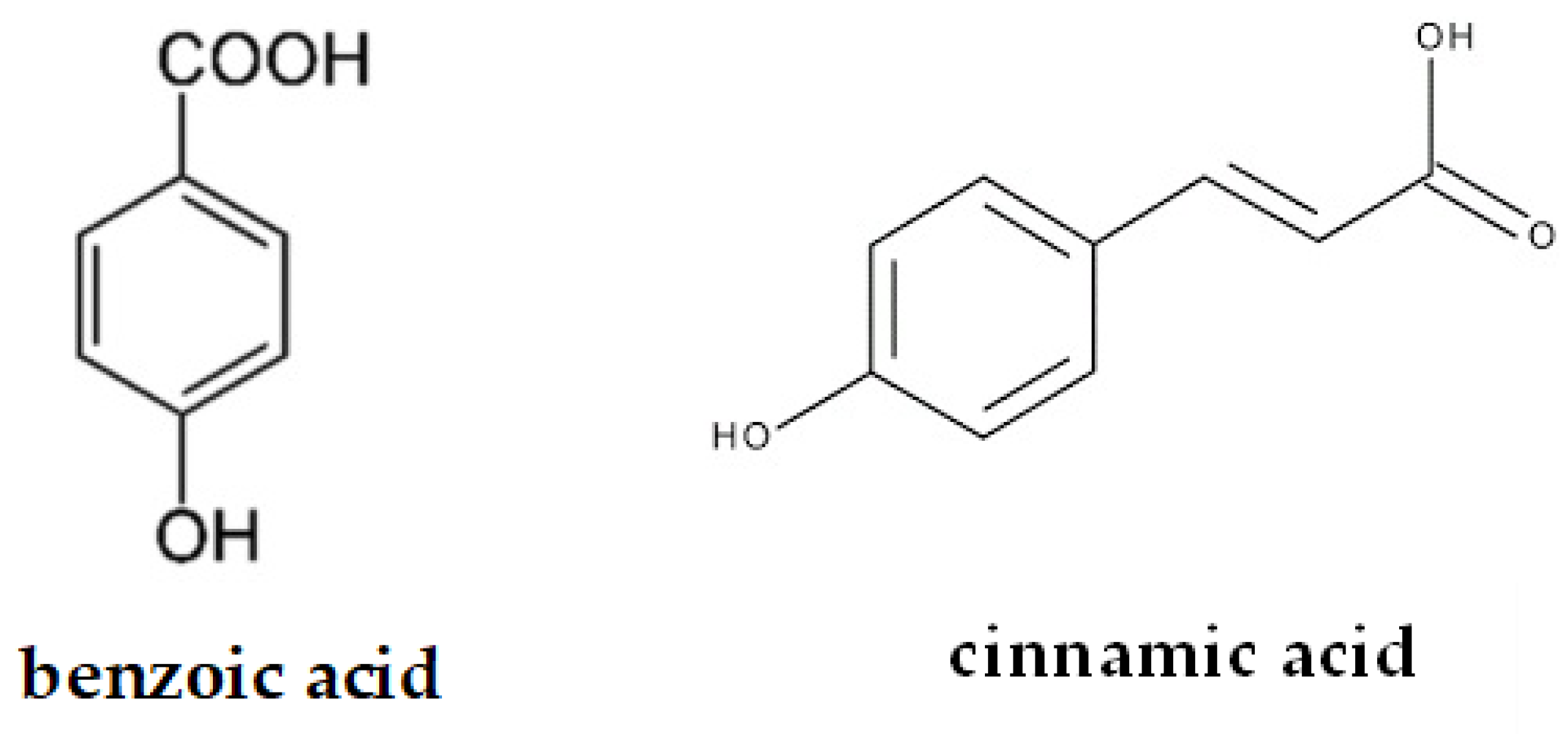

2.1. Phenolic Acids

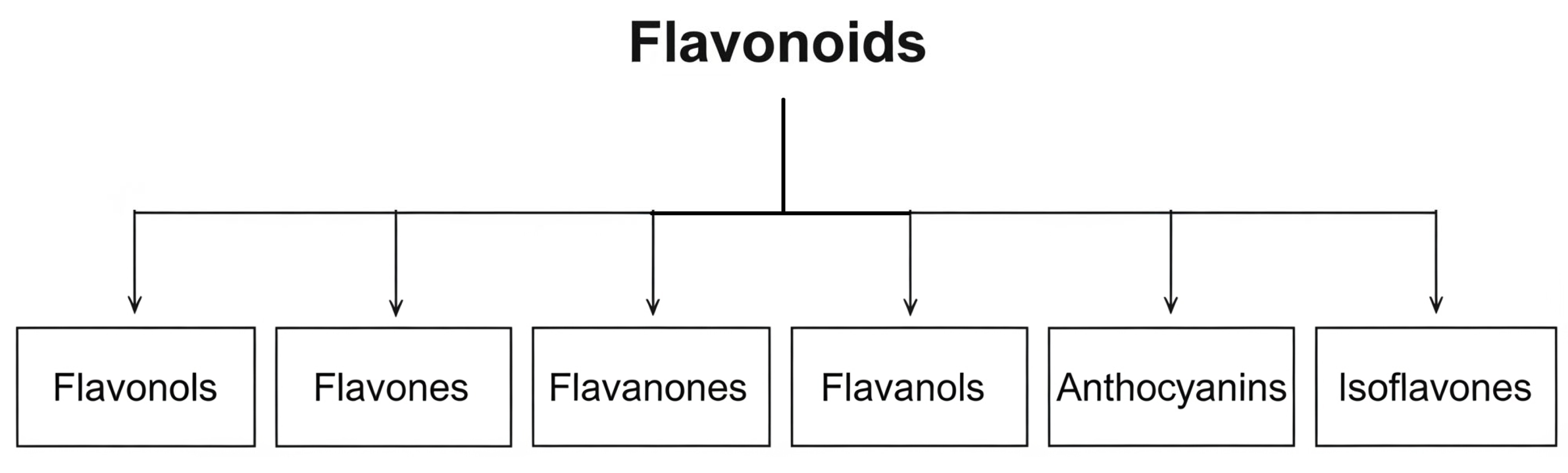

2.2. Flavonoids

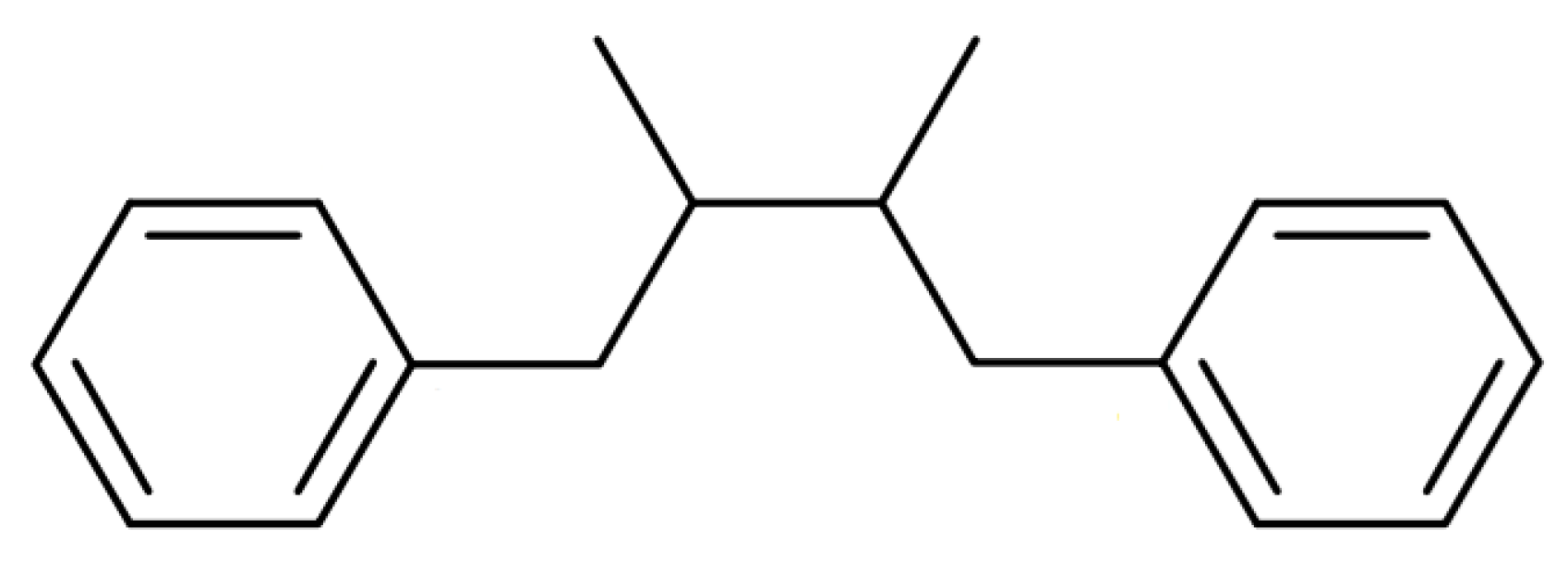

2.3. Lignans

2.4. Stilbenes

3. Phenolic Compounds in the Control of Hypertension and Their Mechanisms of Action

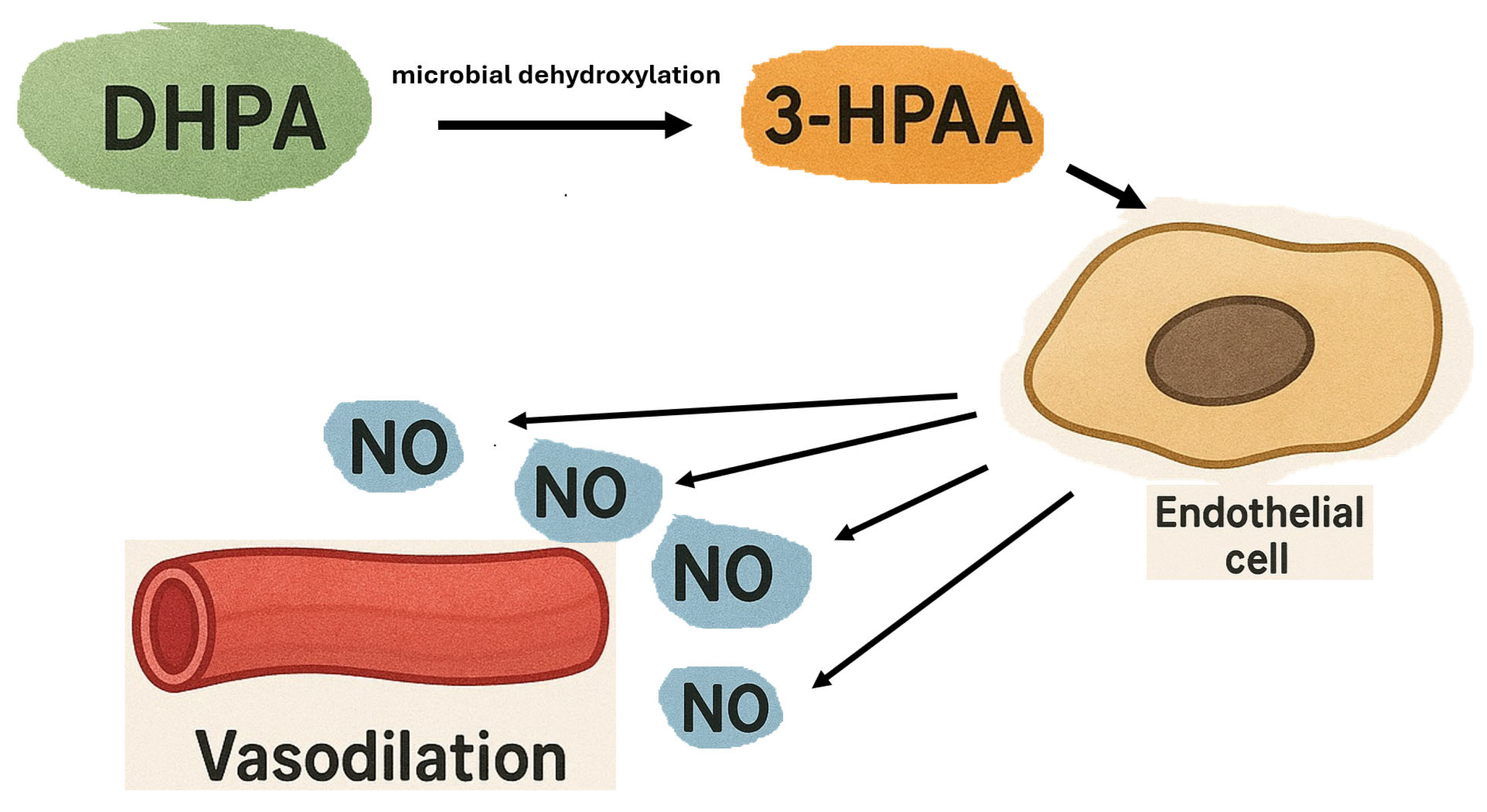

3.1. Phenolic Compounds in the Treatment of Hypertension and Endothelial Dysfunction

3.2. Polyphenols in the Reduction in Hypertension Associated with Pregnancy Complications

3.3. Polyphenols in the Treatment of Hypertension During Metabolic Syndrome

3.4. Polyphenols in the Treatment of Hypertension Related to Chronic Kidney Disease

3.5. Limitations of Polyphenolic Compounds in Hypertension Treatment

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Vaduganathan, M.; Mensah, G.A.; Turco, J.V.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 2361–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Causes of death statistics. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Bruksela, Belgia, 2025; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Causes_of_death_statistics (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Hegde, S.M.; Solomon, S.D. Influence of Physical Activity on Hypertension and Cardiac Structure and Function. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2015, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L. Arterial stiffness and hypertension. Clin. Hypertens. 2023, 29, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Xi, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Veeranki, S.P. Uncontrolled hypertension increases risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in US adults: The NHANES III Linked Mortality Study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, R.; Kuniyoshi, N. Hypertension as an Underlying Cause of Headache or Dizziness and the Usefulness of Choto-San for Both Diagnostic and Therapeutic Purposes. Cureus 2024, 16, e66212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajashekar, D.; Liang, J.W. Intracerebral Hemorrhage. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553103/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Levy, D.; Sharma, S.; Farci, F.; Le, J.K. Aortic Dissection. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441963/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Volpe, M.; Gallo, G. Hypertension, coronary artery disease and myocardial ischemic syndromes. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2023, 153, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewska, M.; Chomicka, I.; Małyszko, J. Hypertension in patients with acute kidney injury. Wiad. Lek. 2019, 72, 2199–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettehad, D.; Emdin, C.A.; Kiran, A.; Anderson, S.G.; Callender, T.; Emberson, J.; Chalmers, J.; Rodgers, A.; Rahimi, K. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 387, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.B.; Rizvi, S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2009, 2, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasawa, M.M.G.; Mohan, C. Fruits as Prospective Reserves of Bioactive Compounds: A Review. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018, 8, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuper-Szablewska, K.; Perkowski, J. Phenolic Acids in Cereal Grain: Occurrence, Biosynthesis, Metabolism and Role in Living Organisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coman, V.; Vizireanu, V.; Botez, E.; Popescu, A.M.; Mihalcea, L.A. Hydroxycinnamic acids and human health: Recent advances. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safe, S.; Jayaraman, A.; Chapkin, R.S.; Howard, M.; Mohankumar, K.; Shrestha, R. Flavonoids: Structure-Function and Mechanisms of Action and Opportunities for Drug Development. Toxicol. Res. 2021, 37, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Wang, G. Isoflavonoid metabolism in leguminous plants: An update and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1368870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, M.D.S.S.; Behrens, M.D.; Moragas-Tellis, C.J.; Penedo, G.X.M.; Silva, A.R.; Gonçalves-de-Albuquerque, C.F. Flavonols and Flavones as Potential anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Compounds. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 9966750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Sahana, G.R.; Nagella, P.; Joseph, B.V.; Alessa, F.M.; Al-Mssallem, M.Q. Flavonoids as Potential Anti-Inflammatory Molecules: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, J.A.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Neveu, V.; Medina-Ramon, A.; M’Hiri, N.; Lobato, P.G.; Manach, C.; Knox, K.; Eisner, R.; Wishart, D.; et al. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: A major update of the Phe-nol-Explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database 2013, 2013, bat070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleano, M.; Oteiza, P.I.; Fraga, C.G. Cocoa, chocolate, and cardiovascular disease. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2009, 54, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, G.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Schwartz, S.J. Flavones: Food Sources, Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addi, M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Abid, M.; Tungmunnithum, D.; Elamrani, A.; Hano, C. An Overview of Bioactive Flavonoids from Citrus Fruits. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikanthan, M.; Muthu, S.; Krishnan, K.; Altemimi, A.B.; Haider, N.N.; Govindan, L.; Selvakumari, J.; Alkanan, Z.T.; Cacciola, F.; Francis, Y.M. A comprehensive review on anthocyanin-rich foods: Insights into extraction, medicinal potential, and sustainable applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 17, 101245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, S.; Haytowitz, D.B.; Holden, J.M. USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3.1; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Nutrient Data Laboratory: Beltsville, MD, USA, 2014. Available online: http://www.ars.usda.gov/nutrientdata/flav (accessed on 1 March 2018).

- Akele, M.L.; Nega, Y.; Belay, N.; Kassaw, S.; Derso, S.; Adugna, E.; Desalew, A.; Arega, T.; Tegenu, H.; Mehari, B. Effect of roasting on the total polyphenol content and antioxidant activity of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) seeds grown in Ethiopia. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patyra, A.; Kołtun-Jasion, M.; Jakubiak, O.; Kiss, A.K. Extraction Techniques and Analytical Methods for Isolation and Characterization of Lignans. Plants 2022, 11, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, I.; Biasiotto, G.; Holm, F.; di Lorenzo, D. Cereal Lignans, Natural Compounds of Interest for Human Health? Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Dwyer, J.; Adlercreutz, H.; Scalbert, A.; Jacques, P.; McCullough, M.L. Dietary lignans: Physiology and potential for cardiovascular disease risk reduction. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 571–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.T.; Xue, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.F.; Xun, H.; Guo, Q.R.; Tang, F.; Sun, J.; Qi, F.F. Lignans and phenylpropanoids from the liquid juice of Phyllostachys edulis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3241–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milder, I.E.; Feskens, E.J.; Arts, I.C.; Bueno de Mesquita, H.B.; Hollman, P.C.; Kromhout, D. Intake of the plant lignans secoisolariciresinol, matairesinol, lariciresinol, and pinoresinol in Dutch men and women. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1202–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagumo, M.; Ninomiya, M.; Oshima, N.; Itoh, T.; Tanaka, K.; Nishina, A.; Koketsu, M. Comparative analysis of stilbene and benzofuran neolignan derivatives as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors with neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sák, M.; Dokupilová, I.; Kaňuková, Š.; Mrkvová, M.; Mihálik, D.; Hauptvogel, P.; Kraic, J. Biotic and Abiotic Elicitors of Stilbenes Production in Vitis vinifera L. Cell Culture. Plants 2021, 10, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valletta, A.; Iozia, L.M.; Leonelli, F. Impact of Environmental Factors on Stilbene Biosynthesis. Plants 2021, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biais, B.; Krisa, S.; Cluzet, S.; Da Costa, G.; Waffo-Teguo, P.; Mérillon, J.-M.; Richard, T. Antioxidant and Cytoprotective Activities of Grapevine Stilbenes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 4952–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuršvietienė, L.; Stanevičienė, I.; Mongirdienė, A.; Bernatonienė, J. Multiplicity of effects and health benefits of resveratrol. Medicina 2016, 52, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drioiche, A.; Ailli, A.; Remok, F.; Saidi, S.; Gourich, A.A.; Asbabou, A.; Kamaly, O.A.; Saleh, A.; Bouhrim, M.; Tarik, R.; et al. Analysis of the Chemical Composition and Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Antimicrobial, Anticoagulant, and Antidiabetic Properties of Pistacia lentiscus from Boulemane as a Natural Nutraceutical Preservative. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanthlal, S.; Arya, V.; Paul-Prasanth, B.; Vijayakumar, M.; Rema, S.; Devi, U. Aqueous extract of large cardamom inhibits vascular damage, oxidative stress, and metabolic changes in fructose-fed hypertensive rats. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2021, 43, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharyya, R.N.; Mithila, S.; Rani, S.; Islam, M.A.; Golder, M.; Ahmed, K.S.; Hossain, H.; Dev, S.; Das, A.K. Anti-allergic and Anti-hyperglycemic Potentials of Lumnitzera racemose Leaves: In vivo and In silico Studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 93, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, R.; Islam, M.; Saeed, H.; Ahmad, A.; Imtiaz, F.; Yasmeen, A.; Rathore, H.A. Antihypertensive potential of Brassica rapa leaves: An in vitro and in silico approach. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 996755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, A. Pharmacological evaluation of Typha domingensis for its potentials against diet-induced hyperlipidemia and associated complications. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2022, 21, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, W.R.C.; Belemnaba, L.; Nitiéma, M.; Kaboré, B.; Koala, M.; Ouedraogo, S.; Semde, R.; Ouedraogo, S. Phytochemical study, antioxidant and vasodilatation activities of leafy stem extracts of Flemingiafaginea Guill. & Perr. (Barker), a medicinal plant used for the traditional treatment of arterial hypertension. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2023, 7, 100231. [Google Scholar]

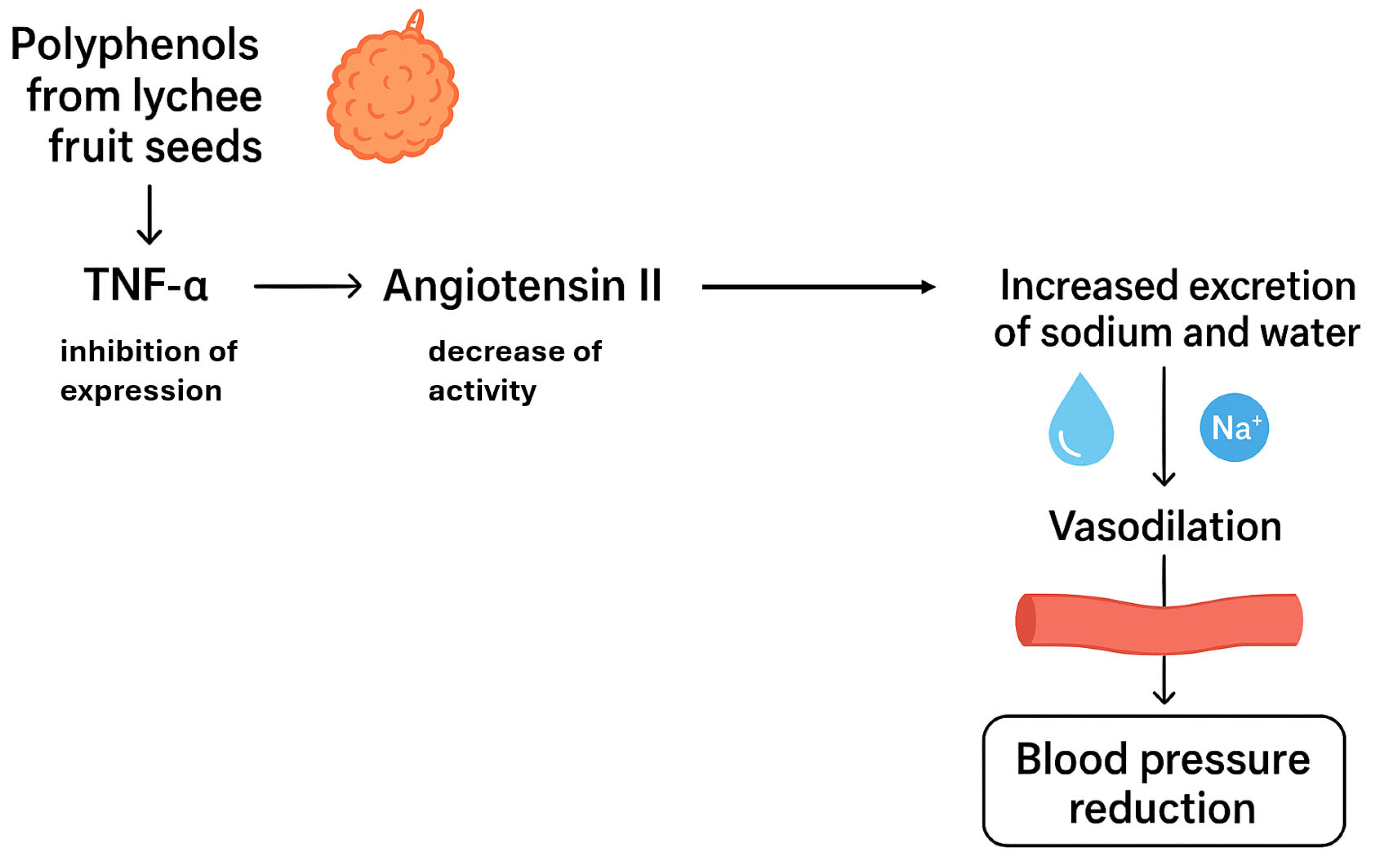

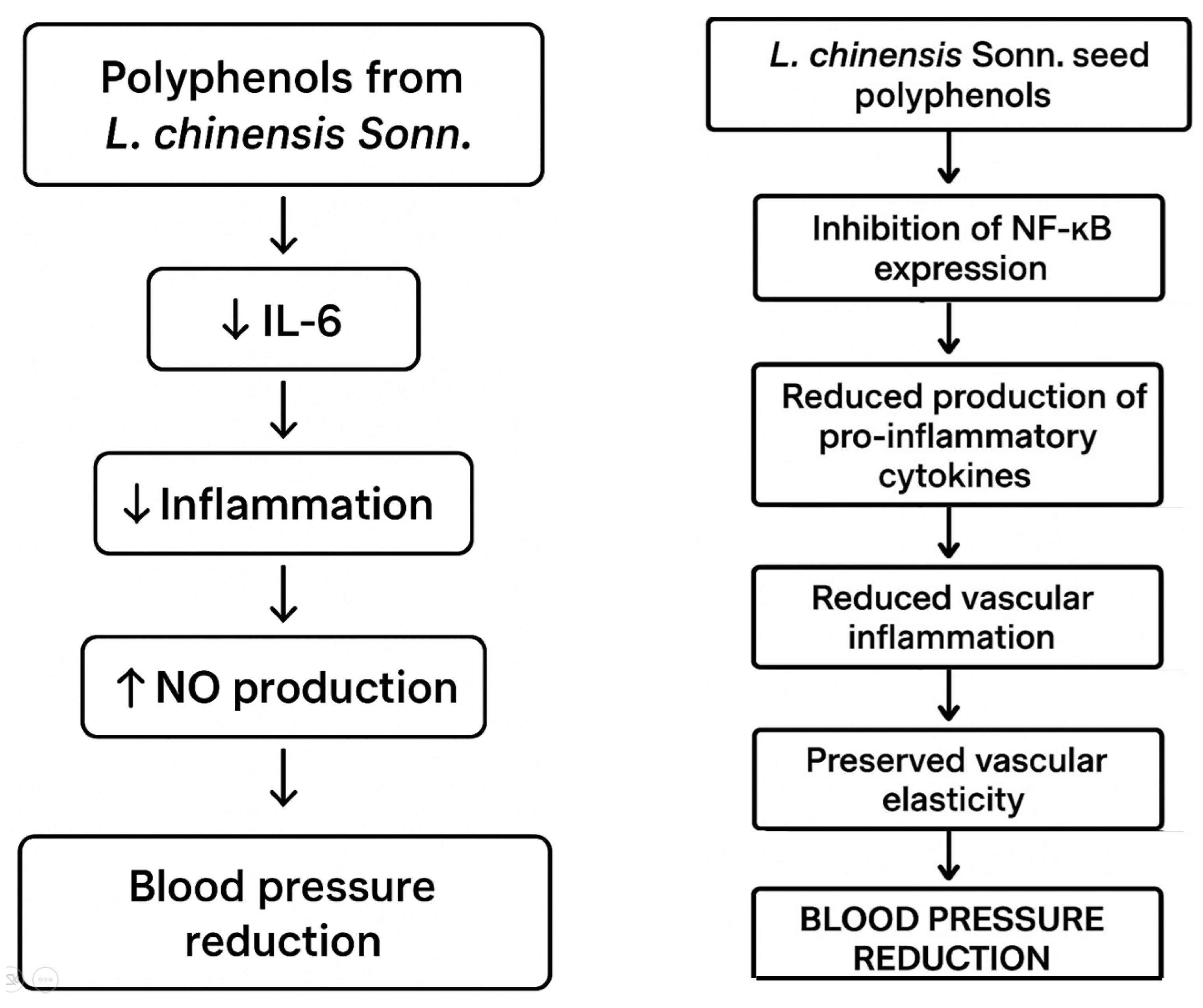

- Yao, Y.; Liu, T.; Yin, L.; Man, S.; Ye, S.; Ma, L. Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Litchi chinensis Seeds Alleviates Hypertension-Induced Renal Damage in Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.N.; Ahmad, S.; Tousif, M.I.; Ahmad, I.; Rao, H.; Ahmad, B.; Basit, A. Profiling of phytochemicals from aerial parts of Terminalia neotaliala using LC-ESI-MS2 and determination of antioxidant and enzyme inhibition activities. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, N.; Hussain, A.I.; Fatima, T.; Alsuwayt, B.; Althaiban, A.K. Bioactivity-Guided Isolation and Antihypertensive Activity of Citrullus colocynthis Polyphenols in Rats with Genetic Model of Hypertension. Medicina 2023, 59, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolić, M.T.; Jurčević, I.L.; Krbavčić, I.P.; Marković, K.; Vahčić, N. Phenolic Content, Antioxidant Capacity and Quality of Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) Products. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2015, 53, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.D.; Melo, A.C.; Westwood, B.M.; Tallant, E.A.; Gallagher, P.E. A Polyphenol-Rich Extract from Muscadine Grapes Prevents Hypertension-Induced Diastolic Dysfunction and Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radović, J.; Suručić, R.; Niketić, M.; Kundaković-Vasović, T. Alchemilla viridiflora Rothm.: The potent natural inhibitor of angiotensin I-converting enzyme. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 1893–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokeswara, A.W.; Afaratu, K.; Prihastama, R.A.; Farida, S. Antihypertensive Effects of Nigella sativa: Weighing the Evidence. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2019, 11, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, R.; Forte, M.; Cotugno, M.; Oppedisano, F.; Carresi, C.; Marchitti, S.; Mollace, V.; Volpe, M.; Rubattu, S. Beneficial Effects of Citrus bergamia Polyphenolic Fraction on Saline Load-Induced Injury in Primary Cerebral Endothelial Cells from the Stroke-Prone Spontaneously Hypertensive Rat Model. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, M.L.; Najjar, R.S.; Danh, J.P.; Knapp, D.; Wanders, D.; Feresin, R.G. Berry consumption mitigates the hypertensive effects of a high-fat, high-sucrose diet via attenuation of renal and aortic AT1R expression resulting in improved endothelium-derived NO bioavailability. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 112, 109225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, R.; Yakami, S.; Kawasaki, T.; Saito, A. Changes in the Polyphenol Content of Red Raspberry Fruits during Ripening. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, R.S.; Mu, S.; Feresin, R.G. Blueberry Polyphenols Increase Nitric Oxide and Attenuate Angiotensin II-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Signaling in Human Aortic Endothelial Cells. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lan, W.; Chen, D. Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) Anthocyanins and Their Functions, Stability, Bioavailability, and Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hounguè, U.; Villette, C.; Tokoudagba, J.M.; Chaker, A.B.; Remila, L.; Auger, C.; Heintz, D.; Gbaguidi, F.A.; Schini-Kerth, V.B. Carissa edulis Vahl (Apocynaceae) extract, a medicinal plant of Benin pharmacopoeia, induces potent endothelium-dependent relaxation of coronary artery rings involving nitric oxide. Phytomedicine 2022, 105, 154370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, A.O.; Ivkin, D.Y.; Zhaparkulova, K.A.; Olusheva, I.N.; Serebryakov, E.B.; Smirnov, S.N.; Semivelichenko, E.D.; Grishina, A.Y.; Karpov, A.A.; Eletckaya, E.I.; et al. Chemical composition and cardiotropic activity of Ziziphora clinopodioides subsp. bungeana (Juz.) Rech. f. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 315, 116660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagopoulou, A.; Theofilis, P.; Karasavvidou, D.; Haddad, N.; Makridis, D.; Tzimikas, S.; Kalaitzidis, R. Pilot study on the effect of flavonoids on arterial stiffness and oxidative stress in chronic kidney disease. World J. Nephrol. 2024, 13, 95262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grujić-Milanović, J.; Jaćević, V.; Miloradović, Z.; Milanović, S.D.; Jovović, D.; Ivanov, M.; Karanović, D.; Vajić, U.J.; Mihailović-Stanojević, N. Resveratrol improved kidney function and structure in malignantly hypertensive rats by restoration of antioxidant capacity and nitric oxide bioavailability. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 154, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández-Sobrino, R.; Soliz-Rueda, J.R.; Margalef, M.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Suárez, M.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B. ACE Inhibitory and Antihypertensive Activities of Wine Lees and Relationship among Bioactivity and Phenolic Profile. Nutrients 2021, 13, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, H.; Hori, M.; Shinomiya, H.; Nakajima, A.; Yamazaki, S.; Sasaki, N.; Sato, T.; Kaneda, T. Rosa centifolia petal extract induces endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation in rat aorta and prevents accumulation of inflammatory factors in human umbilicalve in endothelial cells. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, M.; Arouna, N.; Árvay, J.; Longo, V.; Pucci, L. Sourdough Fermentation Improves the Antioxidant, Antihypertensive, and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Triticum dicoccum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Fuente Muñoz, M.; de la Fuente Fernández, M.; Román-Carmena, M.; Iglesias de la Cruz, M.d.C.; Amor, S.; Martorell, P.; Enrique-López, M.; García-Villalón, A.L.; Inarejos-García, A.M.; Granado, M. Supplementation with Two New Standardized Tea Extracts Prevents the Development of Hypertension in Mice with Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emamat, H.; Asadian, S.; Zahedmehr, A.; Ghanavati, M.; Nasrollahzadeh, J. The effect of barberry (Berberis vulgaris) consumption on flow-mediated dilation and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with hypertension: A randomized controlled trial. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 2607–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szmagara, A.; Krzyszczak-Turczyn, A.; Sadok, I. Fruits of Polish Medicinal Plants as Potential Sources of Natural Antioxidants: Ellagic Acid and Quercetin. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joynt Maddox, K.E.; Elkind, M.S.V.; Aparicio, H.J.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; de Ferranti, S.D.; Dowd, W.N.; Hernandez, A.F.; Khavjou, O.; Michos, E.D.; Palaniappan, L.; et al. Forecasting the Burden of Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke in the United States Through 2050—Prevalence of Risk Factors and Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e65–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Rosario, V.A.; Schoenaker, D.A.J.M.; Kent, K.; Weston-Green, K.; Charlton, K. Association between flavonoid intake and risk of hypertension in two cohorts of Australian women: A longitudinal study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Hou, L. The association between flavonoids intake and hypertension in U.S. adults: A cross-sectional study from The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2024, 26, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Vervoort, J.; Beekmann, K.; Baccaro, M.; Kamelia, L.; Wesseling, S.; Rietjens, I.M.C.M. Interindividual Differences in Human Intestinal Microbial Conversion of (−)-Epicatechin to Bioactive Phenolic Compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 14168–14181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Pourová, J.; Vopršalová, M.; Nejmanová, I.; Mladěnka, P. 3-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid: A Blood Pressure-Reducing Flavonoid Metabolite. Nutrients 2022, 14, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striessnig, J.; Pinggera, A.; Kaur, G.; Bock, G.; Tuluc, P. L-type Ca2+ channels in heart and brain. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Membr. Transp. Signal. 2014, 3, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Brobbey, O.; Qiu, F. Insights into the intestinal bacterial metabolism of flavonoids and the bioactivities of their microbe-derived ring cleavage metabolites. Drug Metab. Rev. 2018, 50, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmanová, I.; Pourová, J.; Mladěnka, P. A Mixture of Phenolic Metabolites of Quercetin Can Decrease Elevated Blood Pressure of Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats Even in Low Doses. Nutrients 2020, 12, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourová, J.; Najmanová, I.; Vopršalová, M.; Migkos, T.; Pilařová, V.; Applová, L.; Nováková, L.; Mladěnka, P. Two Flavonoid Metabolites, 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetic Acid and 4-Methylcatechol, Relax Arteries Ex Vivo and Decrease Blood Pressure In Vivo. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2018, 111, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applova, L.; Karlickova, J.; Warncke, P.; Macakova, K.; Hrubsa, M.; Machacek, M.; Tvrdy, V.; Fischer, D.; Mladenka, P. 4-Methylcatechol, a Flavonoid Metabolite with Potent Antiplatelet Effects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, e1900261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marhuenda, J.; Pérez-Piñero, S.; Arcusa, R.; Victoria-Montesinos, D.; Cánovas, F.; Sánchez-Macarro, M.; García-Muñoz, A.M.; Querol-Calderón, M.; López-Román, F.J. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Determine the Effectiveness of a Polyphenolic Extract (Hibiscus sabdariffa and Lippia citriodora) for Reducing Blood Pressure in Prehypertensive and Type 1 Hypertensive Subjects. Molecules 2021, 26, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molisz, A.; Faściszewska, M.; Wożakowska-Kapłon, B.; Siebert, J. Pulse wave velocity—Reference values and application. Folia Cardiol. 2015, 10, 251–256. [Google Scholar]

- Jaimes, L.; Vinet, R.; Knox, M.; Morales, B.; Benites, J.; Laurido, C.; Martínez, J.L. A Review of the Actions of Endogenous and Exogenous Vasoactive Compounds during the Estrous Cycle and Pregnancy in Rats. Animals 2019, 9, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, H.S.; Kim, D.S.; Ahn, E.H.; Kim, D.W.; Shin, M.J.; Cho, S.B.; Park, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Yeo, E.J.; Choi, Y.J.; et al. Protective effects of Tat-NQO1 against oxidative stress-induced HT-22 cell damage, and ischemic injury in animals. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Singh, V.; Kumari, P.; Singh, R.; Chopra, H.; Emran, T.B. Novel insights on the role of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1: Potential biomarkers for cardiovascular diseases. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022, 84, 104802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdad, M.; Ajebli, M.; Breuer, A.; Khallouki, F.; Owen, R.W.; Eddouks, M. Study of Antihypertensive Activity of Anvillea radiata in L-Name-Induced Hypertensive Rats and HPLC-ESI-MS Analysis. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2020, 20, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, X.; Hu, Z.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Hixson, J.E.; Rao, D.C.; He, J.; Gu, D.; Chen, S. Associations of NADPH oxidase-related genes with blood pressure changes and incident hypertension: The GenSalt Study. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2018, 32, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayeli, V.; Nadipelly, J.; Kadhirvelu, P.; Cheriyan, B.V.; Shanmugasundaram, J.; Subramanian, V. Antinociceptive effect of flavonol and a few structurally related dimethoxy flavonols in mice. Inflammopharmacology 2019, 27, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vors, C.; Rancourt-Bouchard, M.; Couillard, C.; Gigleux, I.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B. Sex May Modulate the Effects of Combined Polyphenol Extract and L-citrulline Supplementation on Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Adults with Prehypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalaf, D.; Krüger, M.; Wehland, M.; Infanger, M.; Grimm, D. The Effects of Oral l-Arginine and l-Citrulline Supplementation on Blood Pressure. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.X.; Zhong, J.C. Gender Differences in Hypertension. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2020, 13, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, J.; Jia, N.; Sun, Q. A network pharmacology study on mechanism of resveratrol in treating preeclampsia via regulation of AGE-RAGE and HIF-1 signalling pathways. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1044775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y. Resveratrol alleviates preeclampsia-like symptoms in rats through a mechanism involving the miR-363-3p/PEDF/VEGF axis. Microvasc. Res. 2022, 146, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, K.; Sequeira, R.P. Drugs for treating severe hypertension in pregnancy: A network meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized clinical trials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrose, D.; Alfonso-Sánchez, S.; McClements, L. Targeting oxidative stress in preeclampsia. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2024, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Passos, R.R.; Santos, C.V.; Priviero, F.; Briones, A.M.; Tostes, R.C.; Webb, R.C.; Bomfim, G.F. Immunomodulatory Activity of Cytokines in Hypertension: A Vascular Perspective. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tain, Y.L.; Jheng, L.C.; Chang, S.K.C.; Chen, Y.W.; Huang, L.T.; Liao, J.X.; Hou, C.Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Resveratrol Butyrate Esters That Have the Ability to Prevent Fat Accumulation in a Liver Cell Culture Model. Molecules 2020, 25, 4199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Z.; Xiong, D.; Wu, M.; Ding, J.L. FFAR2-FFAR3 receptor heteromerization modulates short-chain fatty acid sensing. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillot, E.; Lemay, A.; Allouche, M.; Vitorino Silva, S.; Coppola, H.; Sabatier, F.; Dignat-George, F.; Sarre, A.; Peyter, A.-C.; Simoncini, S.; et al. Resveratrol Reverses Endothelial Colony-Forming Cell Dysfunction in Adulthood in a Rat Model of Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.-X.; Li, C.-X.; Kakar, M.U.; Khan, M.S.; Wu, P.-F.; Amir, R.M.; Dai, D.-F.; Naveed, M.; Li, Q.-Y.; Saeed, M.; et al. Resveratrol (RV): A pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasic, N.; Jakovljevic, V.L.J.; Mitrovic, M.; Djindjic, B.; Tasic, D.; Dragisic, D.; Citakovic, Z.; Kovacevic, Z.; Radoman, K.; Zivkovic, V.; et al. Black chokeberry Aronia melanocarpa extract reduces blood pressure, glycemia and lipid profile in patients with metabolic syndrome: A prospective controlled trial. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 2663–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Bomfim, G.H.; Musial, D.C.; Rocha, K.; Jurkiewicz, A.; Jurkiewicz, N.H. Red wine but not alcohol consumption improves cardiovascular function and oxidative stress of the hypertensive-SHR and diabetic-STZ rats. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2022, 44, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E. Effect of High-Fat Diets on Oxidative Stress, Cellular Inflammatory Response and Cognitive Function. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.C.; Anacleto, S.L.; Matté, C.; Aguiar, O., Jr.; Lajolo, F.M.; Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Ong, T.P. Paternal and/or Maternal Blackberry (Rubus spp.) Polyphenolic Extract Consumption Improved Paternal Fertility and Differentially Affected Female Offspring Antioxidant Capacity and Metabolic Programming in a Mouse Model. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, X.; Feng, H. Vascular Protection of Salicin on IL-1β-Induced Endothelial Inflammatory Response and Damages in Retinal Endothelial Cells. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 1995–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.; Qin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Su, B. NOX4 is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Septic Acute Kidney Injury by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Inflammation. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2863–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evanti, A.; Wargasetia, T.L.; Gunadi, J.W. Role of Nigella sativa L. seed (black cumin) in preventing photoaging (Review). Biomed. Rep. 2025, 23, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solfaine, R.; Muniroh, L.; Sadarman; Apriza, R.P.; Irawan, A. Roles of Averrhoa bilimbi Extract in Increasing Serum Nitric Oxide Concentration and Vascular Dilatation of Ethanol-Induced Hypertensive Rats. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 26, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algharably, E.A.; Meinert, F.; Januszewicz, A.; Kreutz, R. Understanding the Impact of Alcohol on Blood Pressure and Hypertension: From Moderate to Excessive Drinking. Pol. Heart J. 2024, 82, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; Jiang, L.; Ge, W. Kaempferol Prevents Against Ang II-induced Cardiac Remodeling Through Attenuating Ang II-induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 74, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, B.A.; Howell, N.L.; Keller, S.R.; Gildea, J.J.; Padia, S.H.; Carey, R.M. AT2 Receptor Activation Prevents Sodium Retention and Reduces Blood Pressure in Angiotensin II–Dependent Hypertension. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Fincheira, P.; Sanhueza-Olivares, F.; Norambuena-Soto, I.; Cancino-Arenas, N.; Hernandez-Vargas, F.; Troncoso, R.; Gabrielli, L.; Chiong, M. Role of Interleukin-6 in Vascular Health and Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 641734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, M. Recent advancements and comprehensive analyses of butyric acid in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1608658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L.; Li, J.P.; Wu, M.Z.; Wu, J.K.; He, S.Y.; Lu, Y.; Ding, Q.H.; Wen, Y.; Long, L.Z.; Fu, C.G.; et al. Quercetin Protects Against Hypertensive Renal Injury by Attenuating Apoptosis: An Integrated Approach Using Network Pharmacology and RNA Sequencing. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2024, 84, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarbry, F.; Abdelkawy, K.; Moshirian, N.; Abdel-Megied, A.M. The Antihypertensive Effect of Quercetin in Young Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats; Role of Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbarbry, F.; Vermehren-Schmaedick, A.; Balkowiec, A. Modulation of Arachidonic Acid Metabolism in the Rat Kidney by Sulforaphane: Implications for Regulation of Blood Pressure. ISRN Pharmacol. 2014, 2014, 683508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuck, M.; Hellhake, S.; Schebb, N.H. Food Polyphenol Apigenin Inhibits the Cytochrome P450 Monoxygenase Branch of the Arachidonic Acid Cascade. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8973–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Chapter 62—Polyphenols and Polyphenol-Derived Compounds and Contact Dermatitis. In Polyphenols in Human Health and Disease; Watson, R.R., Preedy, V.R., Zibadi, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 793–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatica-Ortega, M.E.; Pastor-Nieto, M.A. Allergic contact dermatitis to phloretin, a luxury cosmetic ingredient, involving a woman with atopic dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2024, 91, 172–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Chodak, A.; Tarko, T. Possible Side Effects of Polyphenols and Their Interactions with Medicines. Molecules 2023, 28, 2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, M.L.; Youssef, F.S.; Gad, H.A.; Wink, M. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP3A4) activity by extracts from 57 plants used in traditional chinese medicine (TCM). Pharmacogn. Mag. 2017, 13, 300–308. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28539725 (accessed on 1 April 2017). [CrossRef]

- Maleki Dana, P.; Sadoughi, F.; Asemi, Z.; Yousefi, B. The role of polyphenols in overcoming cancer drug resistance: A comprehensive review. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2022, 27, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, L.; Byham-Gray, L.; Kurzer, M.; Samavat, H. Hepatotoxicity with High-Dose Green Tea Extract: Effect of Catechol-O-Methyltransferase and Uridine 5′-Diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A4 Genotypes. J. Diet. Suppl. 2023, 20, 850–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Du, J.; Li, Y. Plant polyphenols delay aging: A review of their anti-aging mechanisms and bioavailability. Food Res. Int. 2025, 218, 116900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.V.; Al-Taher, F.; Kalita, D.; Yashin, A.Y.; Yashin, Y.I. Health-Improving Effects of Polyphenols on the Human Intestinal Microbiota: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Niu, K.; Momma, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Chujo, M.; Otomo, A.; Fukudo, S.; Nagatomi, R. Irritable bowel syndrome is positively related to metabolic syndrome: A population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilby, K.; Mathias, H.; Boisvenue, L.; Heisler, C.; Jones, J.L. Micronutrient Absorption and Related Outcomes in People with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, F.; Rovella, V.; Pastore, D.; Bellia, A.; Abete, P.; Donadel, G.; Santini, S.; Beck, H.; Ricordi, C.; Daniele, N.D.; et al. Polyphenols and Ischemic Stroke: Insight into One of the Best Strategies for Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant Polyphenols and Their Potential Benefits on Cardiovascular Health: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, C.; van der Linden, E.L.; Chilunga, F.; van den Born, B.H. International Migration and Cardiovascular Health: Unraveling the Disease Burden Among Migrants to North America and Europe. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.; Chen, S.H.; Li, X.T.; Huang, J.; Mei, R.R.; Qiu, T.Y.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, Q.N.; Xie, C.Y.; et al. Effects of Disease-Related Knowledge on Illness Perception and Psychological Status of Patients With COVID-19 in Hunan, China. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 16, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Z.D.; Chen, S.; Duan, G. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of hypertension risk: A dose-response meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 943–945. [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen, J.A.; Kunutsor, S.K. Fitness and reduced risk of hypertension—Approaching causality. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; AgabitiRosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A. Heart failure risk reduction: Is fit and overweight or obese better than unfit and normal weight? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladele, C.R.; Khandpur, N.; Johnson, S.; Yuan, Y.; Wambugu, V.; Plante, T.B.; Lovasi, G.S.; Judd, S. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Hypertension Risk in the REGARDS Cohort Study. Hypertension 2024, 81, 2520–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, H.; Sen, A.; Aune, D. Fruit and vegetable consumption and the risk of hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2023, 62, 1941–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.M.; Lackland, D.T.; Sutherland, S.E.; Rakotz, M.K.; Williams, J.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Jones, D.W.; Kjeldsen, S.-E.; Campbell, N.R.C.; Parati, G.; et al. PERSPECTIVE—The Growing Global Benefits of Limiting Salt Intake: An urgent call from the World Hypertension League for more effective policy and public health initiatives. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2025, 39, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, M.; Filippini, T.; Whelton, P.K.; Iamandii, I.; Di Federico, S.; Boriani, G.; Vinceti, M. Alcohol Intake and Risk of Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Nonexperimental Cohort Studies. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1701–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Yu, L.; Fu, C.; Xu, K. Assessing the association between smoking and hypertension: Smoking status, type of tobacco products, and interaction with alcohol consumption. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1027988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenolic Component | Type (Group) of Phenolic Compound | Source/Raw Material (Common Name/ Latin Name) | Part of Plant | Type of Biological Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,5-di-o-galloylquinic acid, gallic acid | phenolic acids | the mastic pistachio (Pistacia lentiscus L.) | leaves | antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [38] |

| protocatechuic acid, caffeic acid, syringic acid, 5-o-caffeoylquinic acid | phenolic acids | malabar cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum L.) maton) | flowers/seeds | antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic effect, hypolipidemic effect | [39] |

| myricetin | flavonol | black mangrove/mangrove plant, (Lumnitzera racemosa) | leaves | antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, | [40] |

| rosmarinic acid | phenolic acids | ||||

| 4-ethenyl-2,6-dimethoxy-phenol | metabolic product (derivative) of ferulic acid | cabbage (Brassica rapa) | leaves | antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory | [41] |

| quercetin hyperoside-rhamno-di-hexoside, quercetin-3-o-glucopyranoside | quercetin glycosides | southern cattail (Typha domingensis pers.) | young shoots/leaves | antihypertensive antioxidant diuretic stimulating the excretion of excess sodium ions, preventing fatty liver disease | [42] |

| naringenin | flavanone | ||||

| chlorogenic acid glycoside, ferulic acid glycoside | phenolic acid glycoside | ||||

| myricetin rhamnoside | flavonol | Flemingia faginea Guill. & Perr. | leafy stems | antihypertensive antioxidant | [43] |

| myricetin rutinoside | |||||

| quercetin rutinoside, | |||||

| caffeoyl glucoside | derivatives apigenin | ||||

| 5-caffeoylquinic acid (chlorogenic acid) | phenolic acids | ||||

| gallic acid glycoside | phenolic acid glycoside | ||||

| procyanidin b2, cinnamtannin b1, cinnamtannin b2, procyanidin a1, procyanidindimer a | proanthocyanidin | lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) | seeds | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory diuretic | [44] |

| epicatechin | fla-van-3-ol | ||||

| quercetin | flavonol | ||||

| quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | flavonoid glycoside | ||||

| phlorizin | dihydrochalcone | ||||

| aesculitannin c | tannin | ||||

| cyanidin-3-glucoside | anthocyanin | ||||

| procyanidin b2 cinnamtannin b1 cinnamtannin b2 procyanidin a1 procyanidindimer a | proanthocyanidin | Madagascar almond (Terminalia neotaliala) | leaves/bark | antihypertensive, hypoglycemic | [45] |

| epicatechin | flavanol | ||||

| quercetin | flavonol | ||||

| quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | flavonoid glycoside | ||||

| phlorizin | dihydrochalcone | ||||

| aesculitannin c | tannin | ||||

| cyanidin-3-glucoside | anthocyanin | ||||

| chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, sinapic acid | phenolic acid | watermelon coloquinta (Citrullus colocynthis) | fruit | antihypertensive antioxidant cardioprotective | [46] |

| quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | flavonoid glycoside | ||||

| kaempferol-3-glucoside, myricetin-3-o-glucuronide | flavonol | ||||

| resveratrol | stilben | ||||

| chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, sinapic acid | phenolic acids | black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) | fruit | antihypertensive antioxidant prevents metabolic syndrome antidiabetic | [47] |

| kaempferol-3-glucoside, quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | flavonoid glycoside | ||||

| myricetin-3-o-glucuronide | flavonoid glucuronide | ||||

| resveratrol | stilben | ||||

| catechin, catechin gallate, epicatechin | flavanols | muscat grapes (Vitis vinifera) | skins/seeds | antihypertensive, antioxidant, antiperoxidant | [48] |

| tiliroside | flavonol derivative | Alchemilla viridiflora Rothm., Rosaceae | leaves, flowers | antihypertensive antioxidant | [49] |

| pentose ellagic acid galloyl-hexahydroxydiphenyl-glucose | phenolic acid derivative | ||||

| miquelianin | flavonol glucuronide | ||||

| quercetin | flavone | black cumin, Nigella sativa | seeds | antihypertensive antioxidant | [50] |

| kempferol | flavonone | ||||

| amentoflavone | biflavone | ||||

| neoeriocitrin, neohesperidin, naringin, bruteridine, melitidine | flavonoid glycoside | cultivations of citrus Bergamia Risso & Poiteau | bergamot juice | antihypertensive, antioxidant, vasculogenic (angiogenic), regenerating vascular cells | [51] |

| Catechin, epicatechin | flavan-3-ol | raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) | fruit | antihypertensive antioxidant | [52,53] |

| procyanidin b4 | catechin-(4α→8)-epicatechin dimer | ||||

| Quercetin, quercetin-3-o-glucuronide (miquelianin) | flavonol | ||||

| lambertianin c, sanguiin h-6 | ellagitannin | ||||

| cyanidin-3-o-sophoroside, cyanidin-3-o-sambubiside, cyanidin-3-o-glucoside, cyanidin-3-o-rutinoside | anthocyanins | ||||

| cyanidin-3-o-arabinoside, cyanidin-3-o-galactoside, malvidin-3-o-arabinoside, malvidin-3-o-galactoside, malvidin-3-o-glucoside, paeonidin-3-o-galactoside, paeonidin-3-o-glucoside, petunidin-3-o-galactoside | anthocyanins | highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), variety tifblue, wild lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum), variety rubel | fruit | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory | [54,55] |

| patuletin-7-(6′’-(2-methylbutyryl)-glucoside) | acylated flavonol | umgabunkhomo plant (Carissa edulis Vahl.), the “akan-nsisiri” plant, (Diodia scandens sw.), the plant “African spider flower” (Cleome gynandra L.), | leaves | antihypertensive, antioxidant | [56] |

| catechin 3-o-rutinoside | flavan-3-ols | ||||

| 6-c-glucosylquercetin | flavonoid-3-o-glycosides | ||||

| pinocembrin-7-o-rutinoside | flavanone derivative | Ziziphora clinopodioides subsp. bungeana (Juz.) Rech.f. | leaves | antihypertensive antioxidant | [57] |

| chrysin-7-o-rutinoside (5,7-dihydroxyflavone) | flavone derivative | ||||

| acacetin-7-o-rutinoside | flavone derivative | ||||

| luteolin-7-o-rutinoside | flavone derivative | ||||

| quercetin-3-rutinoside (rutin) | flavonoid glycoside | ||||

| kaempferol quercetin | flavonol | cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) | seeds | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory lowering pulse wave velocity | [58] |

| lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) | leaves | ||||

| cistus /Greek rock rose (Cistus incannus) | leaves/flowers | ||||

| pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) | fruit | ||||

| trans-resweratrol | 3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene | grapevine (Vitis vinifera) | grape skin | antihypertensive, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, angiogenic, renoprotective, podocyte protective, proteinuria reducing | [59] |

| catechin, epicatechin | flavan-3-ol | cabernet grape, garnacha grape, mazuela grape, merlot grape (Vitis vinifera) | wine lees | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory | [60] |

| procyanidin b2 dimer, procyanidin iso1 dimer | proanthocyanidin | ||||

| quercetin, isorhamnetin | flavonol | ||||

| gallic acid | phenolic acid | ||||

| trans-resveratrol piceatannol | stilbene | ||||

| malvidin-3-glucoside malvidin-(6-acetyl)-3-glucoside malvidin-(6-coumaroyl)-3-glucoside (anthocyanins) | anthocyanins | ||||

| quercetin rutoside (rutin), quercetin | flavonol | centifolia rose/“cristata” (Rosa tifola) | flower petals | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory | [61] |

| protocatechuic acid | phenolic acid | ||||

| gallic acid, transferulic acid | phenolic acid | ||||

| quercetin-3-rutoside (rutin), iso-quercitrin, quercetin | flavonol | Tuscan wheat spelt (Triticum dicoccum) | flour | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory | [62] |

| gallic acid | phenolic acid | white tea/ green tea/ black tea/ (Camellia sinensis) | leaf buds/leaves | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory counteracting metabolic syndrome and obesity | [63] |

| epigallocatechin-3-gallate | flavonol | ||||

| quercetin-3-rutoside (rutin), quercetin | flavonol | barberry (Berberis vulgaris L.) | fruit | antihypertensive antioxidant anti-inflammatory regenerating vascular cells | [64,65] |

| cyanidin-3,5-diglucoside, cyanidin-3-glucoside, delphinidin-3,5-diglucoside, petunidin-3-o-β-d-glucoside, pelargonidin-3,5-diglucoside, pelargonidin-3-glucoside | anthocyanins | ||||

| ellagic acid, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid | phenolic acid |

| Type of Phenolic Extract or Phenolic Component | Type of Research | Type of Research Model | Male/ Female | Mechanism of Action Mechanism of Action → Obtained Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenolic extract from Pistacia lentiscus L. | in vivo | Albino mice | male/female | Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity → reduction in inflammation in blood vessels | [38] |

| Polyphenolic extract from highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) and switchberry (Vaccinium virgatum) | ex vivo/ in vivo | Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) | - | Decrease in SAPK/JNK and p38 MAPK activity → Inhibition of monocyte, macrophage and T lymphocyte activation → reduction in inflammation. Increase in expression of NRF2 → Activation of SOD1 and NAD(P)H:NQO1 gene expression → increased antioxidant protection in vascular endothelial cells. Increase in expression of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1, Hmox1) → Reduction in inflammatory processes. Reduction phosphorylation of NF-κB p65 → Reduction of pro-inflammatory gene expression encoding cytokines and chemokines. | [54,79] |

| Polyphenol extract from the skin and seeds of muscat grapes (Vitis vinifera ‘Muscat’) | in vivo | Sprague Dawley rats | male | Reduction in left ventricular filling pressure → improved diastolic function Reduction in cardiomyocyte growth. Reduction in oxidative DNA damage to cardiomyocytes. Increase in expression of SOD1 mRNA and CAT mRNA in the heart → Increased SOD1 and CAT activity in cardiomyocytes. | [48] |

| Polyphenol extract from Alchemilla viridiflora Rothm. | in vitro | ACE Kit-WST | - | Inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme by blocking the enzyme’s active site. | [49] |

| Polyphenol extract from bergamot fruit (Citrus bergamia) of the Risso & Poiteau variety | in vivo/ex vivo | stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR rats) primary cerebral endothelial cells isolated from newborn SHRSP rat brains | male/female | Reduction in oxidative stress in cerebral vascular endothelial cells → limiting blood vessel damage. Stimulating angiogenesis in the brain. Stimulating endothelial cell migration → accelerating the repair process of damaged vessels. | [51] |

| polyphenol extract from blackberry (Rubus L.) and raspberry (Rubus idaeus L.) | in vivo/ in vitro | C57BL/6 mice Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) | male | Inhibition of NADPH oxidase expression in cardiomyocytes, adipocytes, and skeletal muscle cells → decreased O2•- and H2O2, ONOO− production → increased nitric oxide bioavailability Weakening of AT1R receptor expression in the kidneys and aorta → decreased renal sodium reabsorption and vasoconstriction → vasodilation Increase in NRF2 levels in aortic endothelial cells → dephosphorylation of nitric oxide synthesis → increased nitric oxide production → vasodilation | [52,53,99] |

| polyphenol extract from Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) and Lemon verbena (Lippia citriodora) | in vivo | pre-hypertensive or type 1 hypertensive individuals | male/female | Decrease in angiotensin II activity → reduced blood pressure Increase in adiponectin and PPAR-α expression → reduced cytokine and pro-inflammatory molecule expression → reduced inflammation in blood vessels Reduction in NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa B) protein → reduced cytokine and proinflammatory molecule expression → reduced inflammation in blood vessels | [76] |

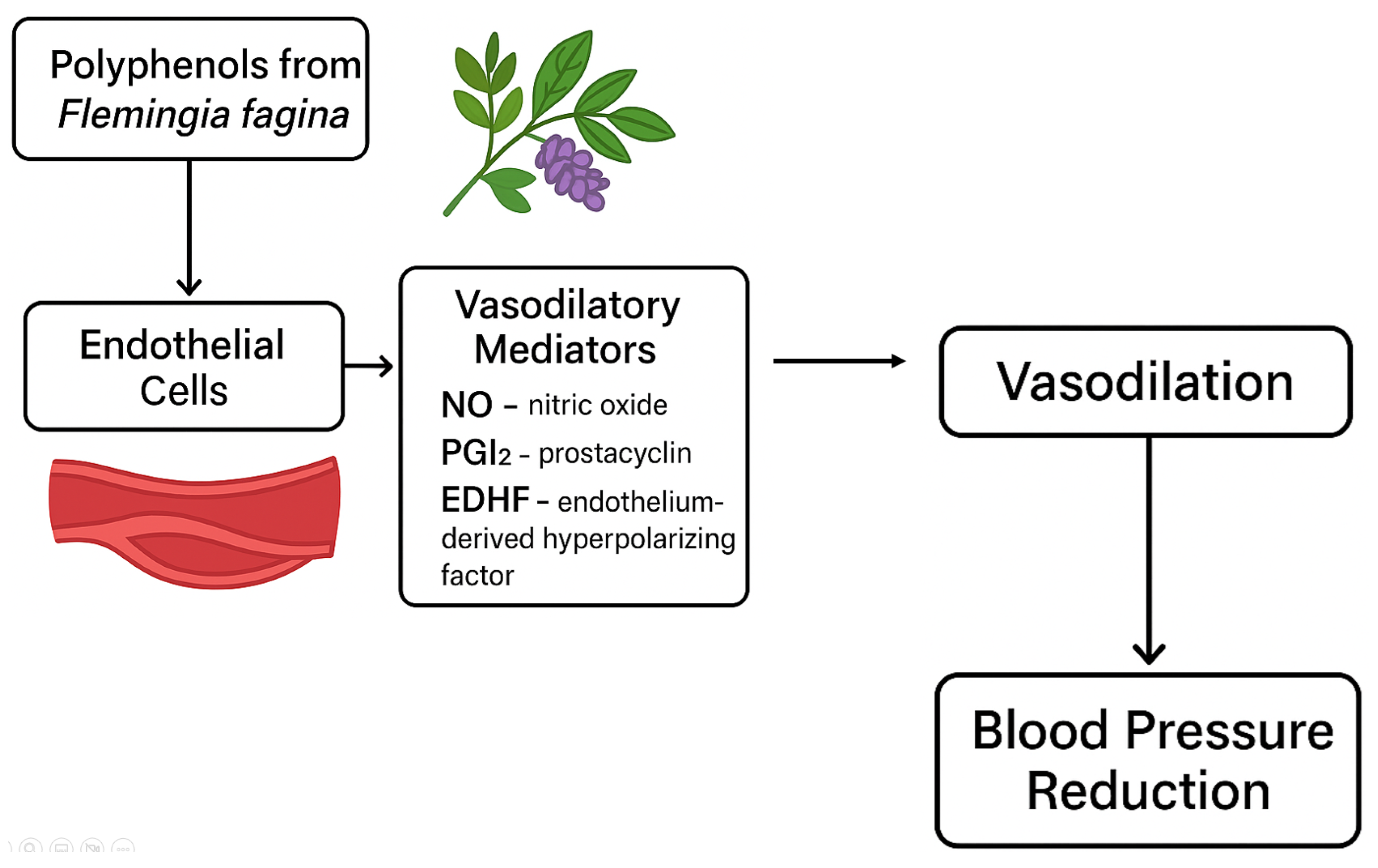

| phenolic extract from the legume Flemingia faginea Guill. & Perr., | ex vivo | mice | male/female | Inhibition of Ca2+ ion influx across the cell membrane → reduction in intracellular Ca2+ ion concentration → relaxation of blood vessels Release of vascular relaxation mediators (NO, PGI2, and EDHF factor) from the endothelium → reduction in blood pressure | [43] |

| polyphenol extract from the leaves and bark of the almond tree from Madagascar (Terminalia neotaliala) | in vitro | α-Glucosidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae | - | Scavenging free oxygen radicals from the vascular endothelium → reducing inflammation Inhibition of α-glucosidase activity in the small intestinal epithelium → reducing postprandial hyperglycemia | [45] |

| polyphenolic wine lees from Cabernet grapes | in vivo | Spontaneously hypertensive rats of the Wistar-Kyoto variety | male/female | Reduction in the activity of angiotensin-converting enzyme → vasodilation | [60] |

| phenolic extract from: the umgabunkhomo plant (Carissa edulis Vahl.), the “akan-nsisiri” plant, Diodia scandens Sw., the plant “African spider flower” Cleome gynandra L., | ex vivo | Wistar rats left circumflex porcine coronary arteries and the thoracic aorta | male | Stimulation of the pathway “nitric oxide synthase-NO-guanylate cyclase (guanylate cyclase)-protein kinase G” → relaxation of smooth muscles in blood vessels | [56] |

| phenolic extract from the leaves of Ziziphora clinopodioides subsp. bungeana (Juz.) Rech.f. | ex vivo | Wistar rats isolated mesenteric vascular bed | male | Stimulation of bradykinin B2 receptors on the surface of endothelial cells → vasodilation Activation of the “NO synthase–NO synthesis–guanylate cyclase–protein kinase G” pathway → vasodilation | [57] |

| phenolic extract from Malabar cardamom seeds (Elettaria cardamomum (L.) Maton) | in vivo | Sprague-Dawley rats | male | Increase in nitric oxide (NO) production → vasodilation | [39] |

| phenolic extract from the fruit of the bilimbi plant (Averrhoa bilimbi L.) | in vivo | Wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) | male | Reducing the breakdown of vascular endothelial cells → limiting vascular dysfunction Reduction in leukocyte infiltration into the adventitia → reduction in fibrosis and stiffening of the arterial wall → reducing the risk of hypertension | [103] |

| phenolic extract from Rosa Tifola | in vivo ex vivo | Rats (Wistar strain) Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells isolated from the vein | male | Activation of nitric oxide synthase → increased NO production Activation of adenylate cyclase → opening of potassium channels → efflux of K+ ions from the cell → closing of calcium channels (L-type) → blocking the influx of Ca2+ ions into the cell → vasodilation Inhibition of TNF-α and NF-κB activity → suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in vascular endothelial cells → reduction in vascular inflammation | [61] |

| phenolic extract from Tuscan wheat Triticum dicoccum | in vitro | Human blood samples The human colonic adenocarcinoma cell (HT-29) line | - | Inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) activity → inhibition of the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II Reduction expression of the mediator IL-8 → reduced inflammatory processes → reduced expression of adhesion glycoproteins (ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) → reduced adhesion of leukocytes to the blood vessel wall → reduced changes in vessel structure → inhibited progression of atherosclerosis | [62,80] |

| phenolic extract from shoots and leaves of Anvillea radiata | in vivo/ ex vivo | Normotensive rats Isolated aortic rings from rats with functional endothelium | male/female | Inhibition of calcium channel activity → reduced calcium ion influx into vascular smooth muscle cells → vasodilation Stimulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) → activation of nitric oxide synthesis → vascular smooth muscle relaxation | [81] |

| phenolic extract from white, black and green tea (Camellia sinensis) | in vivo | C57/BL6J mice | male | Increase in secretion of nitric oxide (NO) → vasodilation | [63] |

| phenolic extract from barberry fruit (Berberis vulgaris L.) | in vivo | individuals subjects with hypertension | men/women | Reduction in the amount of macrophage/monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) in the blood → reduction in vascular inflammation Reduction in the amount of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 glycoproteins in the vessels → reduction in the adhesion and migration of immune cells to the vessel walls → reduction in changes in vessel structure → inhibition of atherosclerosis progression | [64] |

| phenolic extract from Brassica rapa 4-ethenyl-2,6-dimethoxyphenol | in silico/ in vitro | - | - | Angiotensin-converting enzyme I (ACE) inhibition | [41] |

| 3-hydroxyflavone (flavon-3-ol) | in vivo | Swiss albino mice | male | Neutralisation of free oxygen radicals (ROS) → protection of the endothelium of blood vessels | [83] |

| trans-resveratrol | Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway | - | - | Increase in VEGF expression → stimulation of angiogenesis Inhibition of the sFlt1 receptor (soluble tyrosine kinase) → restoration of angiogenesis Reduction in TNF-α activity → reduced inflammation Reduction in STAT protein activity → reduced inflammation | [87] |

| trans-resweratrol | in vivo | Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR rats) | female | Protection of podocytes (cellular cells of the visceral epithelium of the kidney glomeruli), Inhibition of the production of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species → lower 3-nitrotyrosine levels → reduced nitrative stress → reduced vascular inflammation Increase in nitric oxide synthase activity → lower blood pressure | [59] |

| trans-resweratrol | in vivo ex vivo | pregnant rats (Sprague Dawley) isolated endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) | female | Neutralisation of reactive oxygen species → protection of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) from deactivation Increase in proliferation and capillary formation → increased vascular bed volume → reduced blood flow resistance → lower blood pressure | [94] |

| trans-resweratrol | in vivo/in vitro | Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR rats) | male | Inhibition of β1-adrenergic receptors in the cells of the juxtaglomerular apparatus of the kidneys → weakening of renin secretion → weakening of the activation of the RAAS → reducing water and sodium retention in the body → dilation of blood vessels → lowering of blood pressure | [97] |

| resveratrol butyrate | in vivo | Hep G2 (a human liver cancer cell line) Virgin Sprague Dawley (SD) rats | female | Reduction in oxidative damage to the kidneys → lower blood pressure Increase in expression of the short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) receptor → activation of FFAR3 (GPR41) receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells by SCFA → vasodilation → lower blood pressure | [92,93] |

| quercetin | in vivo | Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR rats) | male/female | Inhibition of CYP4A activity → reduction in hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (vasoconstructors) → reduction in vasoconstriction Inhibition of epoxide hydrolase activity → inhibition of the degradation of bioactive epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (vasodilators) → vasodilation | [110] |

| Phenolic Product/Supplement | Recommended Polyphenol Dose | Anthropometric Characteristics of Target Consumers | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| phenolic extract from muscat grape skins and seeds (Vitis vinifera) | 2.3 mg/kg body weight per day | 60 kg body weight | [48] |

| phenolic extract in the form of Cabernet wine less | 73 mL per day | 70 kg body weight | [60] |

| black cumin seeds (Nigella sativa) | 2 g of seeds per day for 12 months | - | [50] |

| a mixture of flavan-3-ols, anthocyanidins and flavonols | 0.235 mg per day | preferably up to 60 years of age | [68] |

| phenolic extract from hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa) flowers and lippia trifoliata (Lippia citriodora) leaves | consumed simultaneously 0.175 g of polyphenols from Hibiscus flowers and 0.325 g of polyphenols from Lippia trifoliata leaves | - | [76] |

| phenolic extract from black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) | 400 mg of polyphenols per day | - | [47] |

| phenolic extract from cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) | 200 mg of polyphenols per day | - | [58] |

| phenolic extract from lemon balm leaves (Melissa officinalis L.) | |||

| phenolic extract from rockrose leaves and flowers (Cistus incannus) | |||

| phenolic extract from pomegranate fruit (Punica granatum) L. | |||

| phenolic extract from cranberry fruit (Vaccinium macrocarpon) + L-citrulline | 548 mg of polyphenols and 2 g of L-citrulline per day | women between 18 and 75 years old | [84] |

| phenolic extract from grape seed (Vitis vinifera) + L-citrulline | 548 mg of polyphenols and 2 g of L-citrulline per day | women between 18 and 75 years old | [84] |

| phenolic extract from barberry fruit (Berberis vulgaris) | 10 g of dried barberry powder per day for 60 days | women and men around 55 years of age | [64] |

| phenolic extract from the fruit of colocynth watermelon (Citrullus colocynthis) | 500 mg per kg of body weight per day | - | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olędzki, R. Polyphenolic Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110665

Olędzki R. Polyphenolic Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110665

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlędzki, Remigiusz. 2025. "Polyphenolic Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110665

APA StyleOlędzki, R. (2025). Polyphenolic Compounds in the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10665. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110665