Deep Sequencing Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes and Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Genotype 4 Patients Resistant to Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Treatment in Egypt

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials/Patients and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VHIR | Vall d’Hebron Institut de Recerca |

| DAAs | Direct-Acting Antivirals |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| RAS | Resistance-Associated Substitutions |

| SVR | Sustained Virologic Response |

| DCV | Daclatasvir |

| EBR | Elbasvir |

| LDV | Ledipasvir |

| OMB | Ombitasvir |

| PTV/r | Paritaprevir/Ritonavir |

| RBV | Ribavirin |

| SOF | Sofosbuvir |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Hepatitis C; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Asselah, T.; Marcellin, P.; Schinazi, R.F. Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus Infection with Direct-Acting Antiviral Agents: 100% Cure? Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2018, 38 (Suppl. S1), 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Perales, C.; Soria, M.E.; García-Cehic, D.; Gregori, J.; Rodríguez-Frías, F.; Buti, M.; Crespo, J.; Calleja, J.L.; Tabernero, D.; et al. Deep-Sequencing Reveals Broad Subtype-Specific HCV Resistance Mutations Associated with Treatment Failure. Antivir. Res. 2020, 174, 104694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzaule, S.; Easterbrook, P.; Latona, A.; Ford, N.P.; Irving, W.; Matthews, P.C.; Vitoria, M.; Duncombe, C.; Giron, A.; McCluskey, S.; et al. Prevalence of Drug Resistance Associated Substitutions in Persons with Chronic Hepatitis C Infection and Virological Failure Following Initial or Re-Treatment with Pan-Genotypic Direct-Acting Antivirals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, H.; Imsirovic, H.; Macphail, G.; Webster, D.; Fraser, C.; Borgia, S.; Liu, H.; Lee, S.; Feld, J.J.; Cooper, C. Resistance-Associated Substitution Testing Trends and Impact on HCV Treatment Outcomes in Canada: A CanHepC-CANUHC Analysis. J. Viral Hepat. 2025, 32, e14058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouyoumjian, S.P.; Chemaitelly, H.; bu-Raddad, L.J. Characterizing Hepatitis C Virus Epidemiology in Egypt: Systematic Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Regressions. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.; Kamel, S.; Waked, I.; Fort, M. Egypt’s Ambitious Strategy to Eliminate Hepatitis C Virus: A Case Study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2021, 9, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population. Plan of Action for the Prevention, Care & Treatment of Viral Hepatitis, Egypt 2014–2018; Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population: Cairo, Egypt, 2014.

- Egyptian Economic and Social Justice Unit. HCV Treatment in Egypt Why Cost Remains a Challenge; Egyptian Economic and Social Justice Unit: Cairo, Egypt, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin, C.; Dvory-Sobol, H.; Svarovskaia, E.S.; Doehle, B.P.; Pang, P.S.; Chuang, S.M.; Ma, J.; Ding, X.; Afdhal, N.H.; Kowdley, K.V.; et al. Prevalence of Resistance-Associated Substitutions in HCV NS5A, NS5B, or NS3 and Outcomes of Treatment with Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawitz, E.; Flamm, C.; Yang, J.C.; Pang, P.S.; Zhu, Y.; Svarovskaia, E.; McHutchison, J.G.; Wyles, D.; Pockros, P. Retreatment of Patients Who Failed 8 or 12 Weeks of Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir-Based Regimens with Ledipasvir/Sofosbuvir for 24 Weeks. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzziello, A.; Marigliano, S.; Loquercio, G.; Cozzolino, A.; Cacciapuoti, C. Global Epidemiology of Hepatitis C Virus Infection: An up-Date of the Distribution and Circulation of Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7824–7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzdęk, M.; Dobrowolska, K.; Flisiak, R.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D. Genotype 4 Hepatitis C Virus-a Review of a Diverse Genotype. Adv. Med. Sci. 2023, 68, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbo, M.C.; Cento, V.; Di, V.M.; Howe, A.Y.M.; Garcia, F.; Perno, C.F.; Ceccherini-Silberstein, F. Hepatitis C Virus Drug Resistance Associated Substitutions and Their Clinical Relevance: Update 2018. Drug Resist. 2018, 37, 17–39, Erratum in Drug Resist. 2018, 40, 40–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlotsky, J.M.; Negro, F.; Aghemo, A.; Berenguer, M.; Dalgard, O.; Dusheiko, G.; Marra, F.; Puoti, M.; Wedemeyer, H.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C: Final Update of the Series(☆). J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218, Erratum in J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, C. Treatment Failure with DAA Therapy: Importance of Resistance. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quer, J.; Gregori, J.; Rodriguez-Frias, F.; Buti, M.; Madejon, A.; Perez-del-Pulgar, S.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Casillas, R.; Blasi, M.; Homs, M.; et al. High-Resolution Hepatitis C Virus Subtyping Using NS5B Deep Sequencing and Phylogeny, an Alternative to Current Methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2015, 53, 219–226, Erratum in J. Clin. Microbiol. 2016, 54, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amer, F.; Yousif, M.M.; Hammad, N.M.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Gregori, J.; Rando-Segura, A.; Nieto-Aponte, L.; Esteban, J.I.; Rodriguez-Frias, F.; Quer, J. Deep-Sequencing Study of HCV G4a Resistancea Ssociated Substitutions in Egyptian Patients Failing DAA Treatment. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 2799–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyuregyan, K.K.; Kichatova, V.S.; Karlsen, A.A.; Isaeva, O.V.; Solonin, S.A.; Petkov, S.; Nielsen, M.; Isaguliants, M.G.; Mikhailov, M.I. Factors Influencing the Prevalence of Resistance-Associated Substitutions in NS5A Protein in Treatment-Naive Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, F.; Gaspareto, K.V.; Lisboa-Neto, G.; Carrilho, F.J.; Mendes-Correa, M.C.; Pinho, J.R.R. Prevalence of Naturally Occurring NS5A Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Patients Infected with Hepatitis C Virus Subtype 1a, 1b, and 3a, Co-Infected or Not with HIV in Brazil. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, P.R.; Komatsu, T.E.; Deming, D.J.; Donaldson, E.F.; O’Rear, J.J.; Naeger, L.K. Impact of Hepatitis C Virus Polymorphisms on Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment Efficacy: Regulatory Analyses and Perspectives. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2430–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perales, C.; Chen, Q.; Soria, M.E.; Gregori, J.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Nieto-Aponte, L.; Castells, L.; Imaz, A.; Llorens-Revull, M.; Domingo, E.; et al. Baseline Hepatitis C Virus Resistance-Associated Substitutions Present at Frequencies Lower than 15% May Be Clinically Significant. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 2207–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Ismail, M.H.; Leitner, T.; Faleo, G.; Elmnan Adem, S.A.; Elamin, M.O.M.E.; Eltreifi, O.; Alwazzeh, M.J.; Fiore, J.R.; Santantonio, T.A. Genetic Subtypes and Natural Resistance Mutations in HCV Genotype 4 Infected Saudi Arabian Patients. Viruses 2021, 13, 1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J.; Müllhaupt, B.; Buggisch, P.; Graf, C.; Peiffer, K.-H.; Matschenz, K.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Antoni, C.; Mauss, S.; Niederau, C.; et al. Long-Term Persistence of HCV Resistance-Associated Substitutions after DAA Treatment Failure. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, M.; Faleo, G.; Farhan Mohamed, A.M.; Morella, S.; Bruno, S.R.; Tundo, P.; Fiore, J.R.; Santantonio, T.A. Resistance Associated Mutations in HCV Patients Failing DAA Treatment. New Microbiol. 2021, 44, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, L.V.; Pedersen, M.S.; Fahnøe, U.; Fernandez-Antunez, C.; Humes, D.; Schønning, K.; Ramirez, S.; Bukh, J. HCV Genome-Wide Analysis for Development of Efficient Culture Systems and Unravelling of Antiviral Resistance in Genotype 4. Gut 2022, 71, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, E.; Ruiz-Jarabo, C.M.; Sierra, S.; Arias, A.; Pariente, N.; Baranowski, E.; Escarmis, C. Emergence and Selection of RNA Virus Variants: Memory and Extinction. Virus Res. 2002, 82, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregori, J.; Colomer-Castell, S.; Ibañez-Lligoña, M.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Campos, C.; Buti, M.; Riveiro-Barciela, M.; Andrés, C.; Piñana, M.; González-Sánchez, A.; et al. In-Host Flat-like Quasispecies: Characterization Methods and Clinical Implications. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, M.E.; Gregori, J.; Chen, Q.; Garcia-Cehic, D.; Llorens, M.; de Avila, A.I.; Beach, N.M.; Domingo, E.; Rodriguez-Frias, F.; Buti, M.; et al. Pipeline for Specific Subtype Amplification and Drug Resistance Detection in Hepatitis C Virus. BMC.Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuiken, C.; Combet, C.; Bukh, J.; Shin, I.; Deleage, G.; Mizokami, M.; Richardson, R.; Sablon, E.; Yusim, K.; Pawlotsky, J.M.; et al. A Comprehensive System for Consistent Numbering of HCV Sequences, Proteins and Epitopes. Hepatology 2006, 44, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Case | Age | Gender | Subtype | Viral Load (IU) | First Treatment | Treatment Period | Second Treatment. Final Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R001 Pre & R002 Post | 1 | 54 | Female | 4a | 5.80 × 105 3.51 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R007 Pre & R039 Post | 3 | 23 | Male | 4a | 5.49 × 106 1.95 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R010 Pre & R009 Post | 4 | 60 | Male | 4a/4o | 2.23 × 107 9.17 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R015 Pre & R016 Post | 5 | 65 | Male | 4o | 7.31 × 105 7.01 × 105 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R036 Pre & R035 Post | 6 | 46 | Female | 4m | 5.82 × 106 1.16 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R037 | 64 | Male | 4a | 3.70 × 105 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R038 | 53 | Male | 4a | 2.00 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R043 | 49 | Male | 4m | 2.88 × 105 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R033 | 51 | Female | 4a | 1.74 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R034 | 62 | Male | 4o | 1.12 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R027 | 47 | Female | 4a | 6.32 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R025 | 56 | Male | 4m | 1.44 × 107 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R008 | 58 | Female | 4a | 9.46 × 105 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R019 | 60 | Male | 4o | 5.76 × 105 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R022 | 49 | Female | 4o | 4.66 × 106 | SOF/DCV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R029 | 49 | Female | 1g | 4.39 × 106 | SOF/DCV/RBV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R031 | 53 | Male | 4o | 4.24 × 106 | SOF/DCV/RBV | 12 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R006 Pre & R005 Post | 2 | 60 | Female | 4a | 1.89 × 106 1.76 × 105 | SOF/PAR/OMB/RBV | 24 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

| R013 | 42 | Female | 4a | 2.91 × 106 | SOF/PAR/OMB/RBV | 24 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R021 | 67 | Male | 4o | 2.86 × 106 | SOF/PAR/OMB/RBV | 24 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R026 | 60 | Male | 4a | 1.26 × 106 | SOF/PAR/OMB/RBV | 24 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX | |

| R024 | 45 | Female | 4a | 6.57 × 106 | SOF/PAR/OMB/RBV | 24 weeks | SOF/VEL/VOX |

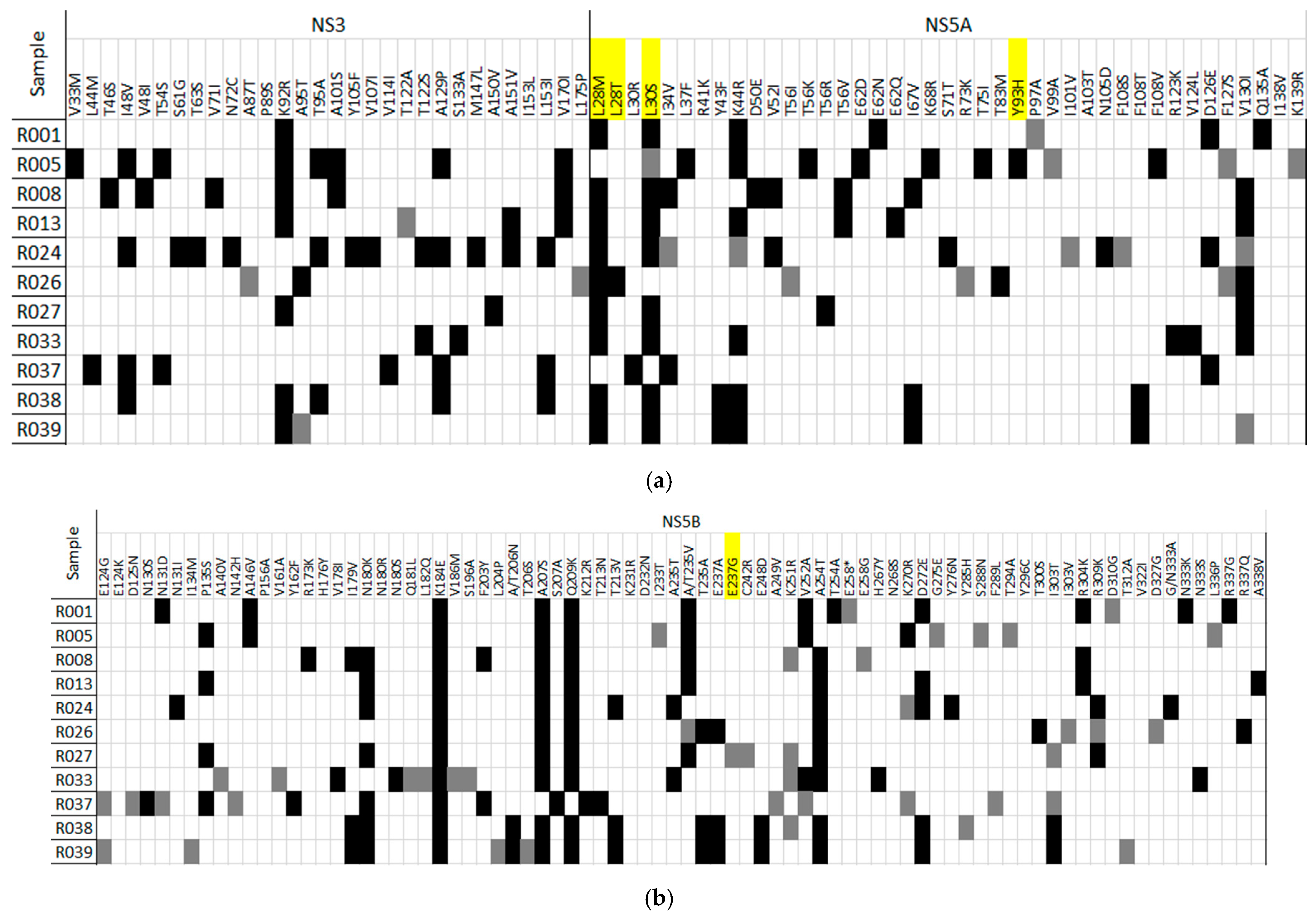

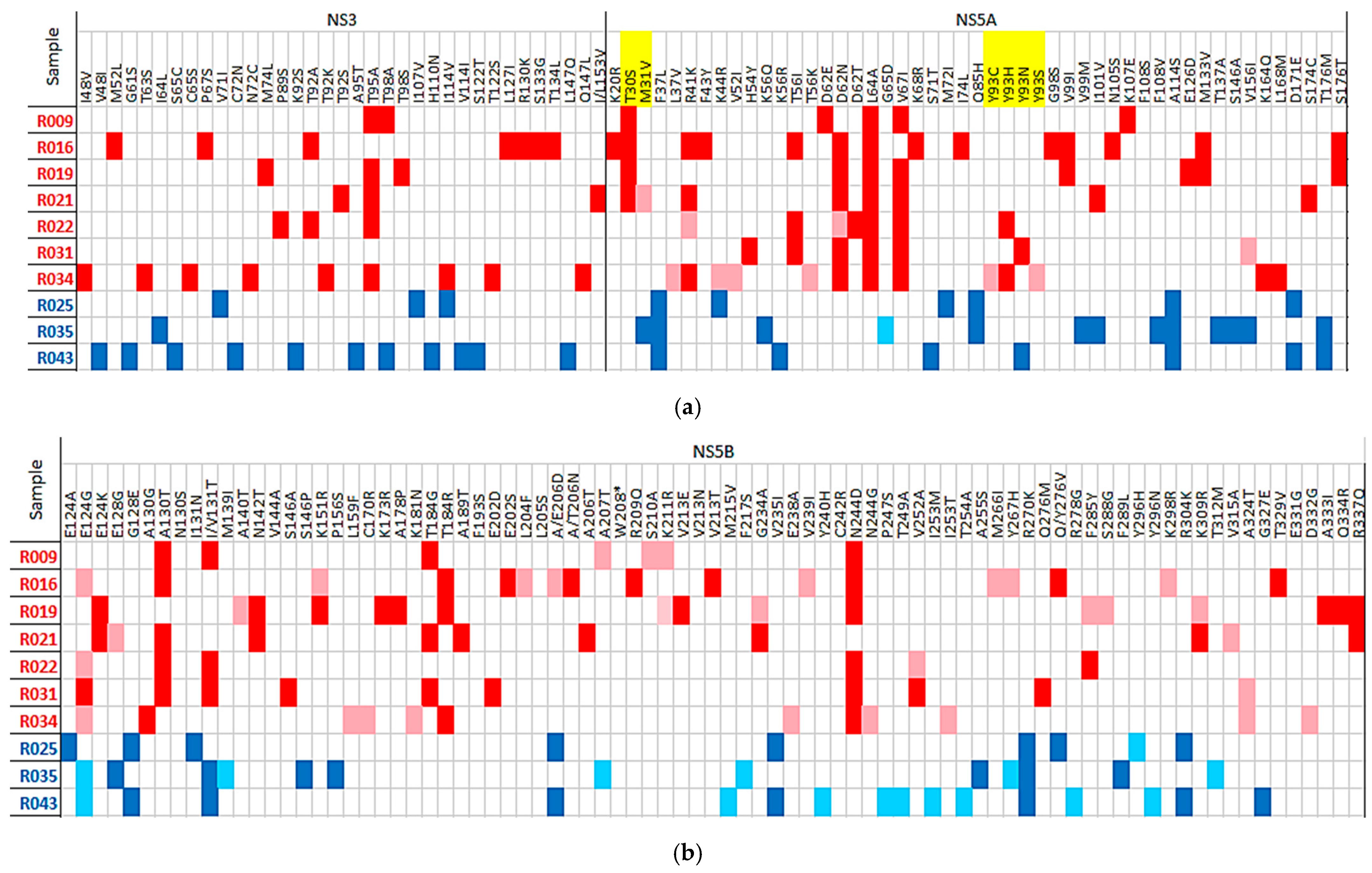

| (a) | HCV Region/Position | Amino Acid Substitution | No. of Patients (%) | Amino Acid Position |

| Substitutions with frequencies >= to 50% in six or more patients | NS3 | K92R | 7 | 92 |

| NS5A | L28M | 8 | 28 | |

| NS5A | L30S | 7 | 30 | |

| NS5A | K44R | 7 | 44 | |

| NS5B1 | N180K | 7 | 180 | |

| NS5B1 | K184E | 12 | 184 | |

| NS5B1 | A207S | 11 | 207 | |

| NS5B1 | Q209K | 11 | 209 | |

| NS5B1 | A254T | 9 | 254 | |

| NS5B2 | D272E | 6 | 272 | |

| (b) | HCV Region | Amino Acid Substitution | Num. Patients | RAS Position |

| Substitutions with frequencies >= to 50% at RAS positions | NS3 | T54S | 1 | 54 |

| NS3 | T122S | 2 | 122 | |

| NS3 | V170I | 3 | 170 | |

| NS5A | L28M | 8 | 28 | |

| NS5A | L28T | 1 | 28 | |

| NS5A | L30S | 7 | 30 | |

| NS5A | L30R | 1 | 30 | |

| NS5A | E62D | 1 | 62 | |

| NS5A | E62N | 1 | 62 | |

| NS5A | E62Q | 1 | 62 |

| Genotype | Region | Oligo | 5′ Position | Sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR | G4a | NS3 | Fw | 3391 | CAGAAACATCMAAGGGGTGGAGACT |

| Rv | 4004 | CTGRGGCACYGCDGGGGGTGT | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6230 | GATCAATGAAGATTGYTCCACYCCAT | ||

| Rv | 6879 | GTGATGGGTCTGTCARCATGGA | |||

| NS5B | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCARCTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8650 | GGGGGAGCCGAGTAYCTCGT | |||

| G4m/G4o | NS3 | Fw | 3412 | TGGAGRCTYCTYGCYCCYAT | |

| Rv | 4064 | ACYTTRGTGCTCTTGCCGCT | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6217 | AGACGYCTYCACMAGTGGATYAAYGA | ||

| Rv | 6989 | CABGTGGCYTTCARDGATGGRGC | |||

| NS5B | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCARCTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8631 | TCATRGCCTCCGTGAAGGC | |||

| G1g | NS3 | Fw | 3354 | CGCAGGGGYAGGGAAGT | |

| Rv | 4008 | AGGTCTGRGGYACGGCTG | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6213 | AGGCGACTYCACACRTGGAT | ||

| Rv | 6879 | GTGATGGRTCTGTGAGCATRGACG | |||

| NS5B | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCAACTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8638 | GGGRGCGGAGTACCTGGT | |||

| Nested | G4a | NS3 | Fw | 3490 | GGGACACCAATGARAATTGTGGT |

| Rv | 3982 | GARTTGTCAGTGAACACTGGTGATC | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6299 | CGTGCTGAGTGACTTCAAGACGTGGCT | ||

| Rv | 6735 | GGTGTAGYCTGAYGCCGTCYA | |||

| NS5B1 | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCARCTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8409 | CCCACRTAGAGTCTYTCTGTGAG | |||

| NS5B2 | Fw | 8254 | CNTAYGAYACCMGNTGYTTTGACTC | ||

| Rv | 8641 | GARTAYCTGGTCATAGCNTCCGTGAA | |||

| G4m/G4o | NS3 | Fw | 3481 | AGCCTYACYGGCARRGAYACCAATG | |

| Rv | 3983 | TTGTCRGTRAAVACYGGRGACCTCAT | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6288 | TGGGTYTGCACYGTHYTRAGTGACT | ||

| Rv | 6811 | CCVACYACRAAMGWGTTGAGGCC | |||

| NS5B1 | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCARCTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8409 | TGCTGTTRTACATSGGRCCRCC | |||

| NS5B2 | Fw | 8254 | CNTAYGAYACCMGNTGYTTTGACTC | ||

| Rv | 8641 | GARTAYCTGGTCATAGCNTCCGTGAA | |||

| G1g | NS3 | Fw | 3486 | GGCCGVGAYAAMAACMMGGTGG | |

| Rv | 3988 | GGGGTRGAATTGTCMGTGWAHACDGG | |||

| NS5A | Fw | 6282 | TGGGACTGGAHTGCAYGGT | ||

| Rv | 6729 | GGCGYACCCCRTCYASCT | |||

| NS5B1 | Fw | 7952 | CCACATCAACTCCGTGTGG | ||

| Rv | 8389 | CCGACGTACARTCTCTCRGTGAG | |||

| NS5B2 | Fw | 8254 | CNTAYGAYACCMGNTGYTTTGACTC | ||

| Rv | 8641 | GARTAYCTGGTCATAGCNTCCGTGAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Cehic, D.; Mosbeh, A.; A. Gad, H.; Gomaa, A.I.; Ibañez Lligoña, M.; Gregori, J.; Colomer-Castell, S.; Campos, C.; Rodriguez-Frias, F.; Esteban, J.I.; et al. Deep Sequencing Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes and Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Genotype 4 Patients Resistant to Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Treatment in Egypt. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110649

Garcia-Cehic D, Mosbeh A, A. Gad H, Gomaa AI, Ibañez Lligoña M, Gregori J, Colomer-Castell S, Campos C, Rodriguez-Frias F, Esteban JI, et al. Deep Sequencing Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes and Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Genotype 4 Patients Resistant to Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Treatment in Egypt. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110649

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Cehic, Damir, Asmaa Mosbeh, Heba A. Gad, Asmaa Ibrahim Gomaa, Marta Ibañez Lligoña, Josep Gregori, Sergi Colomer-Castell, Carolina Campos, Francisco Rodriguez-Frias, Juan Ignacio Esteban, and et al. 2025. "Deep Sequencing Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes and Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Genotype 4 Patients Resistant to Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Treatment in Egypt" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110649

APA StyleGarcia-Cehic, D., Mosbeh, A., A. Gad, H., Gomaa, A. I., Ibañez Lligoña, M., Gregori, J., Colomer-Castell, S., Campos, C., Rodriguez-Frias, F., Esteban, J. I., Kohla, M. S., Abdel-Rahman, M. H., & Quer, J. (2025). Deep Sequencing Analysis of Hepatitis C Virus Subtypes and Resistance-Associated Substitutions in Genotype 4 Patients Resistant to Direct-Acting Antiviral (DAA) Treatment in Egypt. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110649