Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Active Nuclei During Drosophila Embryogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

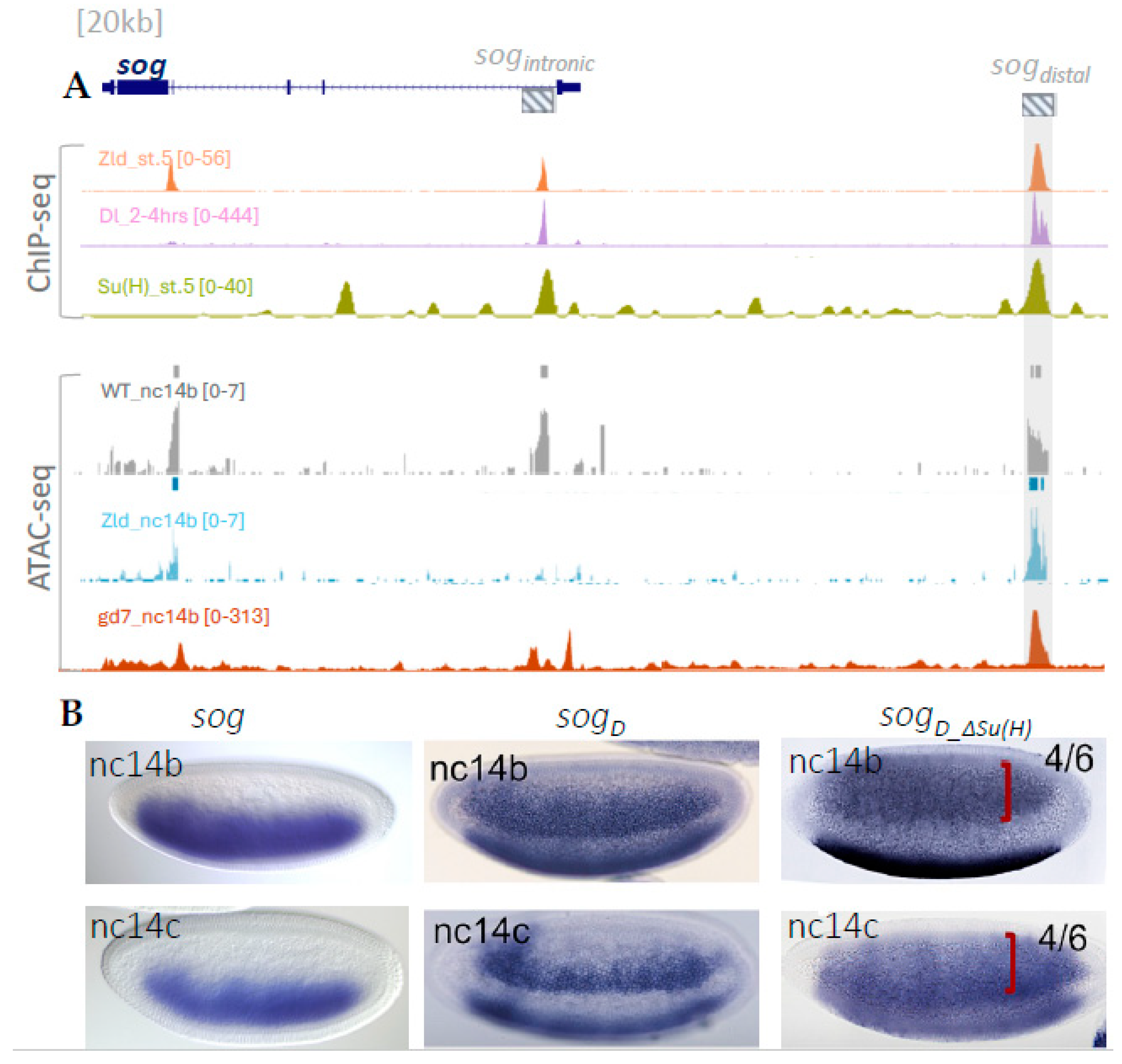

2.1. Analysis of Transcription Factor Binding and Chromatin Accessibility at the sog_distal Enhancer

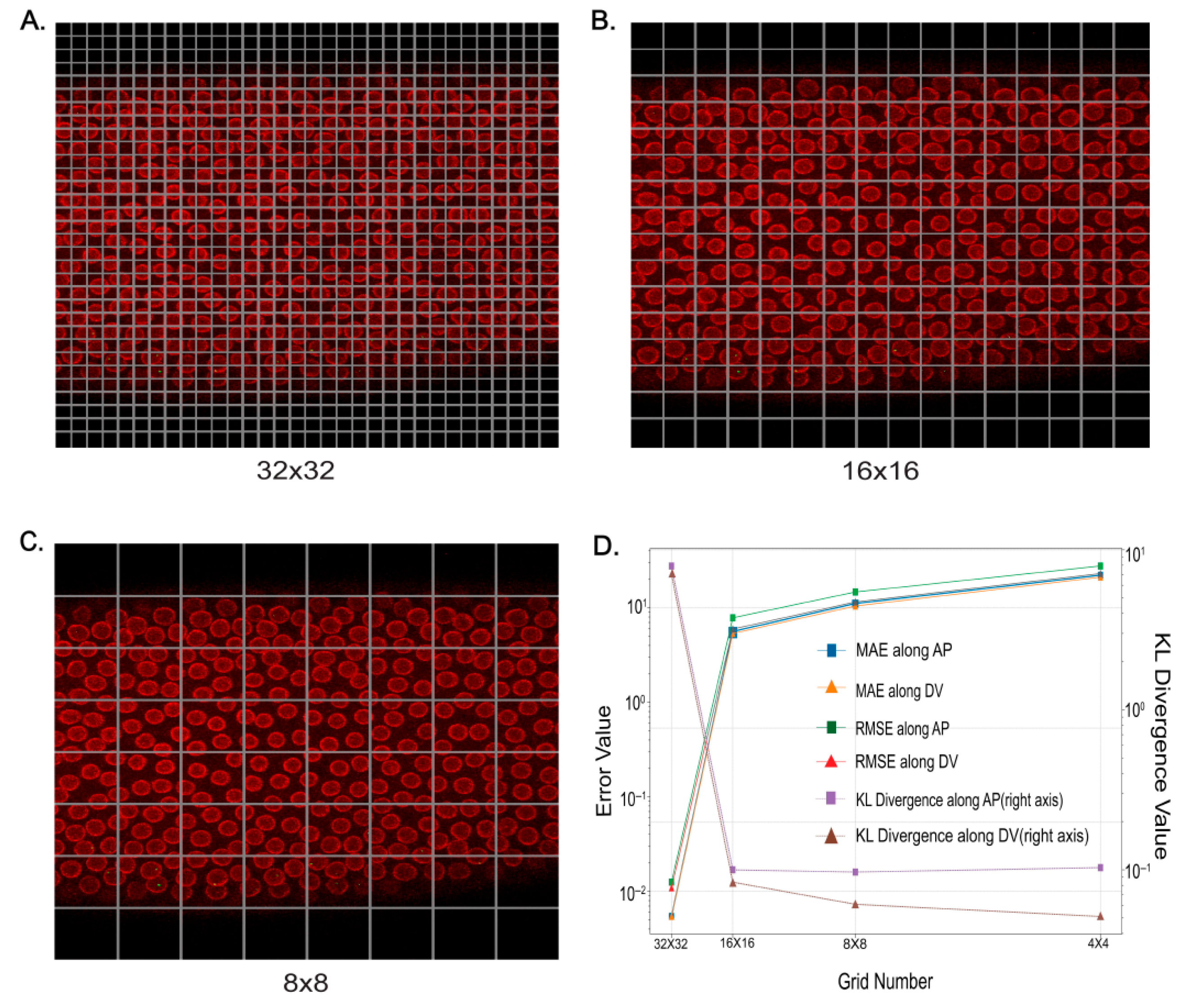

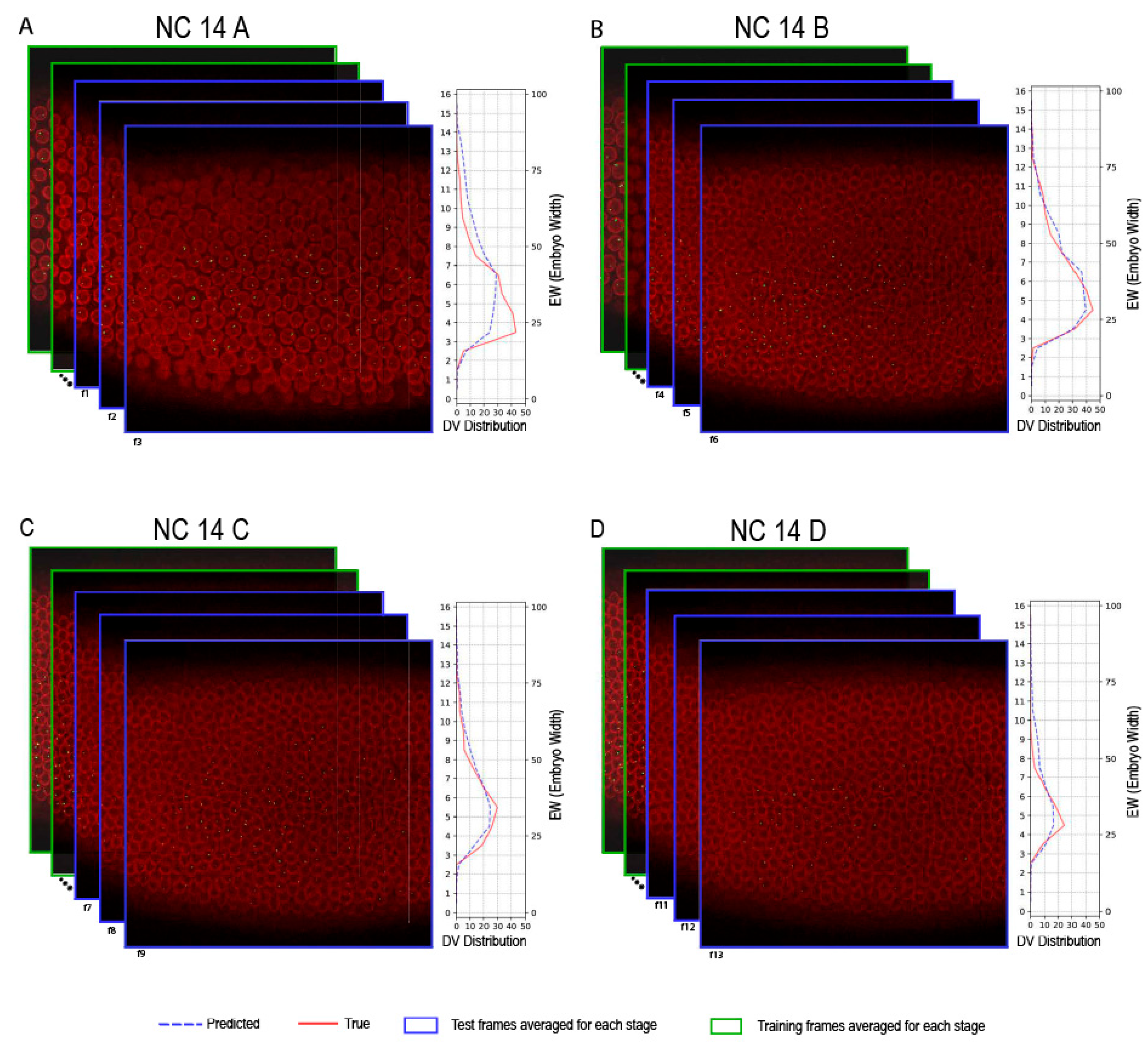

2.2. Comprehensive Analysis of Super-Resolution Live Movies

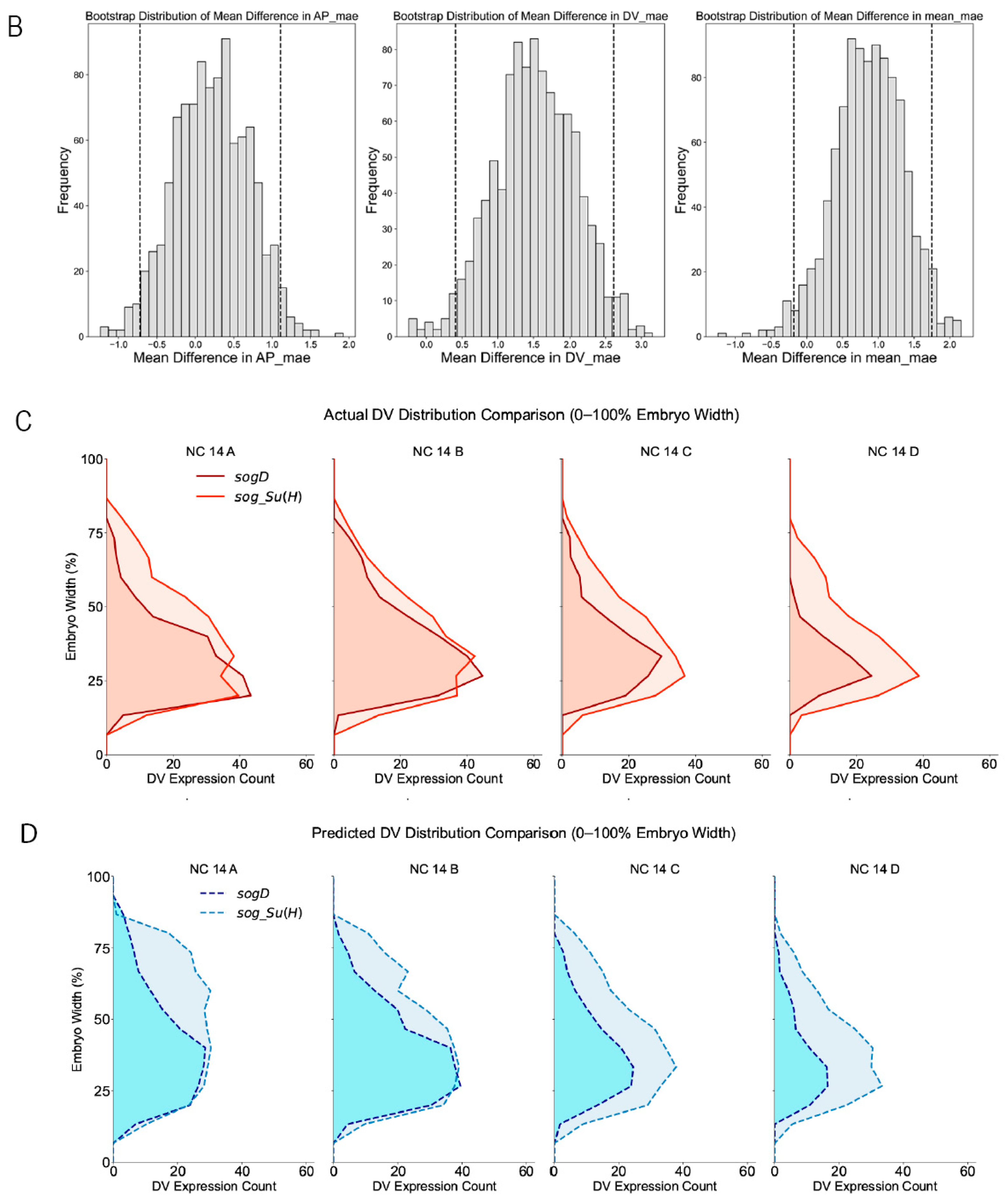

2.3. Comparative Evaluation of sogD and sogD Su(H)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. ChIP-Seq and ATAC-Seq Analysis

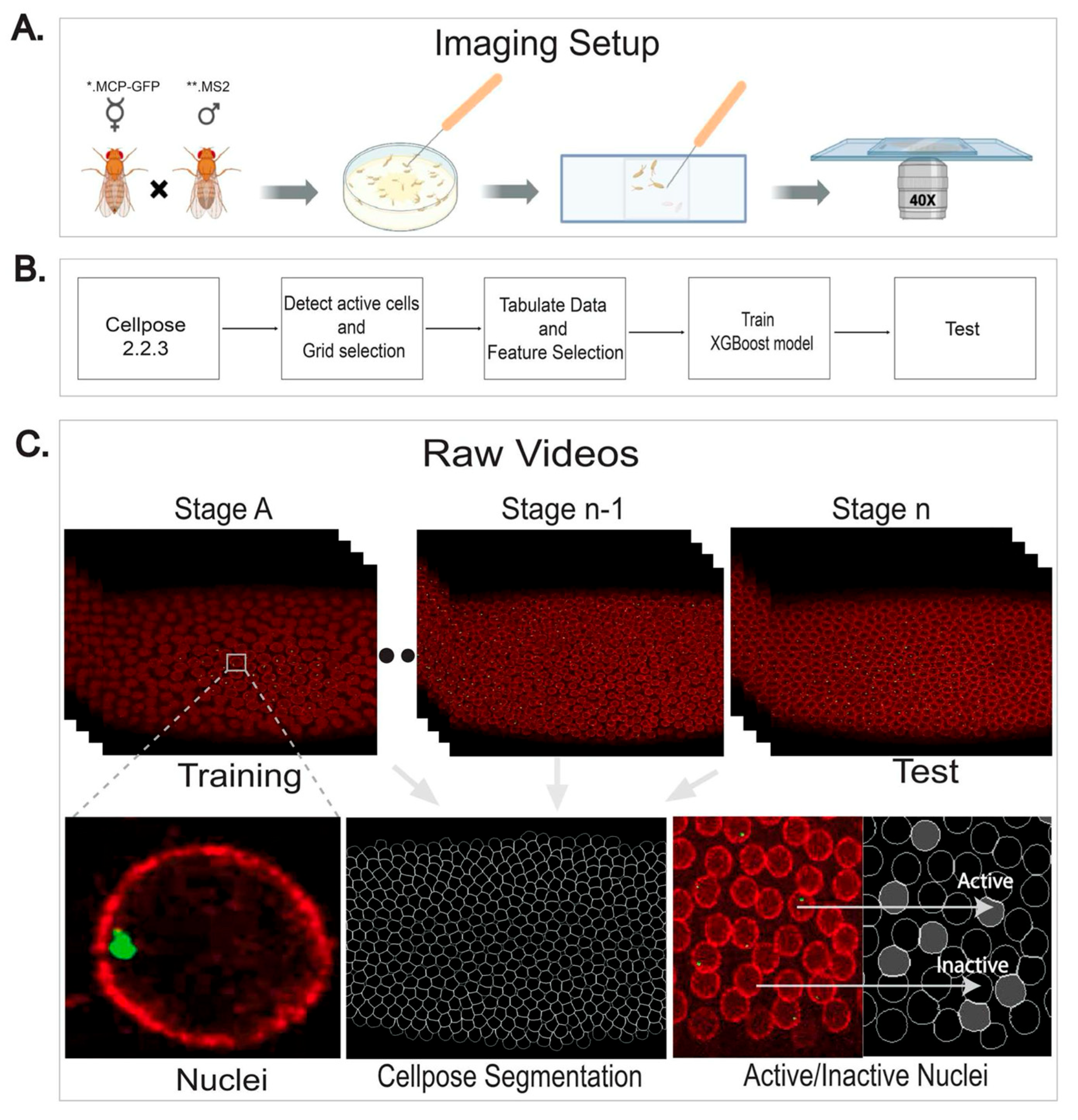

4.2. Experimental Set-Up for MS2.MCP Embryo Collection

4.3. Live Imaging

4.4. Data Preprocessing

4.5. Training

4.6. Evaluation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koromila, T.; Stathopoulos, A. Distinct roles of broadly expressed repressors support dynamic enhancer action and change in time. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunipace, L.; Saunders, A.; Ashe, H.L.; Stathopoulos, A. Autoregulatory feedback controls sequential action of cis-regulatory modules at the brinker locus. Dev. Cell 2013, 26, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.K.; Prescott, S.L.; Wysocka, J. Ever-changing landscapes: Transcriptional enhancers in development and evolution. Cell 2016, 167, 1170–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, M.W.; Bothma, J.P.; Luu, R.D.; Levine, M. Precision of hunchback expression in the drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, 2247–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, E.E.M.; Levine, M. Developmental enhancers and chromosome topology. Science 2018, 361, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, H.G.; Tikhonov, M.; Lin, A.; Gregor, T. Quantitative imaging of transcription in living drosophila embryos links polymerase activity to patterning. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2140–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.; Heist, T.; Levine, M.; Fukaya, T. Visualization of transvection in living drosophila embryos. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnie, A.; Plat, A.; Korkmaz, C.; Bothma, J.P. Precisely timed regulation of enhancer activity defines the binary expression pattern of fushi tarazu in the drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2839–2850.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crocker, J.; Abe, N.; Rinaldi, L.; McGregor, A.P.; Frankel, N.; Wang, S.; Alsawadi, A.; Valenti, P.; Plaza, S.; Payre, F.; et al. Low affinity binding site clusters confer hox specificity and regulatory robustness. Cell 2015, 160, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerber, A.; van Otterdijk, S.; Bruggeman, F.J.; Tutucci, E. Understanding spatiotemporal coupling of gene expression using single molecule rna imaging technologies. Transcription 2023, 14, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantale, K.; Mueller, F.; Kozulic-Pirher, A.; Lesne, A.; Victor, J.M.; Robert, M.C.; Capozi, S.; Chouaib, R.; Bäcker, V.; Mateos-Langerak, J.; et al. A single-molecule view of transcription reveals convoys of rna polymerases and multi-scale bursting. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Manno, G.; Soldatov, R.; Zeisel, A.; Braun, E.; Hochgerner, H.; Petukhov, V.; Lidschreiber, K.; Kastriti, M.E.; Lönnerberg, P.; Furlan, A.; et al. Rna velocity of single cells. Nature 2018, 560, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayao, M.T.; Trevino, A.; Kim, H.; Ruffalo, M.; D’aNgio, H.B.; Preska, R.; Duvvuri, U.; Mayer, A.T.; Bar-Joseph, Z. Deriving spatial features from in situ proteomics imaging to enhance cancer survival analysis. Bioinformatics 2023, 39 (Suppl. S1), i140–i148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenelon, K.D.; Borad, P.; Rout, B.; Malidarreh, P.B.; Nasr, M.S.; Luber, J.M.; Koromila, T. Su(H) Modulates Enhancer Transcriptional Bursting in Prelude to Gastrulation. Cells 2024, 13, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.J.; Weilert, M.; Krueger, S.; Pampari, A.; Liu, H.-Y.; Yang, A.W.H.; Morrison, J.A.; Hughes, T.R.; Rushlow, C.A.; Kundaje, A.; et al. Chromatin accessibility in the Drosophila embryo is determined by transcription factor pioneering and enhancer activation. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 1562–1577.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenelon, K.D.; Gao, Y.; Borad, P.; Abbasi, P.; Pachter, L.; Koromila, T. Cell-specific occupancy dynamics between the pi oneer-like factors Opa and Oc in the developing Drosophila embryo. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1122334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowlkes, C.C.; Hendriks, C.L.; Keränen, S.V.; Weber, G.H.; Rübel, O.; Huang, M.Y.; Chatoor, S.; DePace, A.H.; Simirenko, L.; Henriquez, C.; et al. A quantitative spatiotemporal atlas of gene expression in the drosophila blastoderm. Cell 2008, 133, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Johnston, J.; Zeitlinger, J. ChIP-nexus enables improved detection of in vivo transcription factor binding footprints. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.M.; Li, X.-Y.; Kaplan, T.; Botchan, M.R.; Eisen, M.B. Zelda Binding in the Early Drosophila melanogaster Embryo Marks Regions Subsequently Activated at the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, B.C.; Pentcheva-Hoang, T.; Carstens, J.L.; Zheng, X.; Wu, C.-C.; Simpson, T.R.; Laklai, H.; Sugimoto, H.; Kahlert, C.; Novitskiy, S.V.; et al. Depletion of carcinoma associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell 2014, 25, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koromila, T.; Gao, F.; Iwasaki, Y.; He, P.; Pachter, L.; Gergen, J.P.; Stathopoulos, A. Odd-paired is a pioneer-like factor that coordinates with Zelda to control gene expression in embryos. eLife 2020, 9, e59610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koromila, T.; Stathopoulos, A. Broadly expressed repressors integrate patterning across orthogonal axes in embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8295–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, B. Imaging transcriptional dynamics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 52, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimmett, V.L.; Dejean, M.; Fernandez, C.; Trullo, A.; Bertrand, E.; Radulescu, O.; Lagha, M. Quantitative imaging of transcription in living drosophila embryos reveals the impact of core promoter motifs on promoter state dynamics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenelon, K.D.; Krause, J.; Koromila, T. Opticool: Cutting-edge transgenic optical tools. PLoS Genet. 2024, 20, e1011208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, C.; Ashe, H.L. Live imaging and quantitation of nascent transcription using the ms2/mcp system in the drosophila embryo. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T.; Ferraro, T.; Roelens, B.; Chanes, J.D.L.H.; Walczak, A.M.; Coppey, M.; Dostatni, N. Live imaging of bicoid-dependent transcription in drosophila embryos. Curr. Biol. 2013, 23, 2135–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature List | Mae |

|---|---|

| n, Ripley’s K-function | 3.799 |

| m2, n, Ripley’s K-function | 3.86 |

| m2, m1 AP, n, Ripley’s K-function | 3.92 |

| Ripley’s K-function | 3.93 |

| m2, m1 AP, m1 DV, Ripley’s K-function | 3.94 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malidarreh, P.B.; Borad, P.; Rout, B.; Makridou, A.; Abbasi, S.; Nasr, M.S.; Saurav, J.R.; Fenelon, K.D.; Veerla, J.P.; Luber, J.M.; et al. Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Active Nuclei During Drosophila Embryogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110338

Malidarreh PB, Borad P, Rout B, Makridou A, Abbasi S, Nasr MS, Saurav JR, Fenelon KD, Veerla JP, Luber JM, et al. Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Active Nuclei During Drosophila Embryogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110338

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalidarreh, Parisa Boodaghi, Priyanshi Borad, Biraaj Rout, Anna Makridou, Shiva Abbasi, Mohammad Sadegh Nasr, Jillur Rahman Saurav, Kelli D. Fenelon, Jai Prakash Veerla, Jacob M. Luber, and et al. 2025. "Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Active Nuclei During Drosophila Embryogenesis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110338

APA StyleMalidarreh, P. B., Borad, P., Rout, B., Makridou, A., Abbasi, S., Nasr, M. S., Saurav, J. R., Fenelon, K. D., Veerla, J. P., Luber, J. M., & Koromila, T. (2025). Machine Learning-Driven Prediction of Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Active Nuclei During Drosophila Embryogenesis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10338. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110338