1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) and asthma are chronic allergic diseases that have become increasingly prevalent worldwide, particularly among children. Both conditions involve complex immune dysregulation, impaired epithelial barrier function, and chronic inflammation. In recent years, accumulating evidence has highlighted the critical role of gut microbiota in shaping host immunity and maintaining systemic homeostasis. Dysbiosis—an imbalance in the gut microbial community—has been associated with heightened susceptibility to allergic diseases, including AD and asthma.

The etiology of atopic dermatitis (AD) development is complex and involves abnormal immune and inflammatory responses, including skin barrier defects, exposure to environmental factors, and neuropsychological factors [

1,

2,

3,

4]. About 70~80% of patients with AD present with external forms of AD and an increased serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) level [

5]. Scratching from intense itching leads to skin damage, which leads to the release of cytokines and chemokines and, consequently, a further increase in skin permeability. This then further promotes the entry of allergens into the skin, which is also a cause of AD [

6].

The use of animal models to simulate human AD patterns has greatly expanded our understanding of the disease and allowed for in-depth studies of its pathogenesis. Mice, dogs, and guinea pigs can develop symptoms similar to AD; however, mouse models are mainly used because they are easy to establish and maintain, are low cost, and most importantly, the genetic strain can be manipulated. Since the Nc/Nga mouse was first described as a spontaneously occurring AD model in 1997 [

7], many mouse models have been developed. These animal models can be divided into three groups: (1) models induced by epidermal epicutaneous sensitizers; (2) transgenic mice selected to overexpress or lack certain genes; and (3) mice with spontaneously occurring AD-like skin lesions. These models display many features of human AD, allowing for a better understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of the disease. These models are based on skin injury and allergen sensitization AD, which is AD induced by repeated epidermal sensitization of depilated skin with ovalbumin (OVA), and have been used in five mouse strains so far, including BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice [

8]. Epidermally sensitized mice show increased scratching behavior and skin lesions characterized by epidermal and dermal thickening, CD4+ T-cell and eosinophil infiltration, and Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. In addition, increased expressions of OVA-specific IgG1, IgE, and IgG2a in serum have been reported, with higher expressions of IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IFN-γ in the spleen cells of OVA-sensitized mice. In addition, OVA-sensitized mice have been reported to show increased asthmatic hyperresponsiveness after aerosol administration of OVA, a feature similar to that of most patients with AD [

9,

10].

Despite growing interest in the gut–skin–lung axis, the relationship between specific bacterial strains and allergic disease remains underexplored. Notably, the roles of

Bacteroides plebeius,

Bacteroides ovatus,

Faecalibacterium duncaniae,

Faecalibacterium taiwanense, and

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the pathogenesis of AD and asthma are not well understood. Some studies suggest that there are lower levels of

B. plebeius in children with asthma and reduced

F. prausnitzii in patients with AD [

11].

F. duncaniae, a recently reclassified butyrate-producing species, has shown anti-inflammatory activity in murine asthma models [

12], yet human data remain limited. The immunoregulatory potential of

B. ovatus has been suggested in early-life microbiome studies [

13], while

F. taiwanense, a novel species isolated in Taiwan, remains largely uncharacterized in allergic disease.

B. plebeius, originally identified in Japanese individuals with seaweed-rich diets, can degrade porphyran and may influence mucosal immunity [

14].

B. ovatus, a common gut commensal, supports IgA production and gut barrier function.

F. duncaniae and

F. prausnitzii are key producers of butyrate, which strengthens epithelial integrity and promotes anti-inflammatory regulatory T-cell responses [

15].

Given the limited number of comprehensive studies on this topic, we aim to investigate the associations and underlying mechanisms of these strains in the context of AD and asthma. By elucidating their immunomodulatory effects, we hope to contribute to the development of microbiome-based therapeutic strategies for allergic diseases and the atopic march.

2. Results

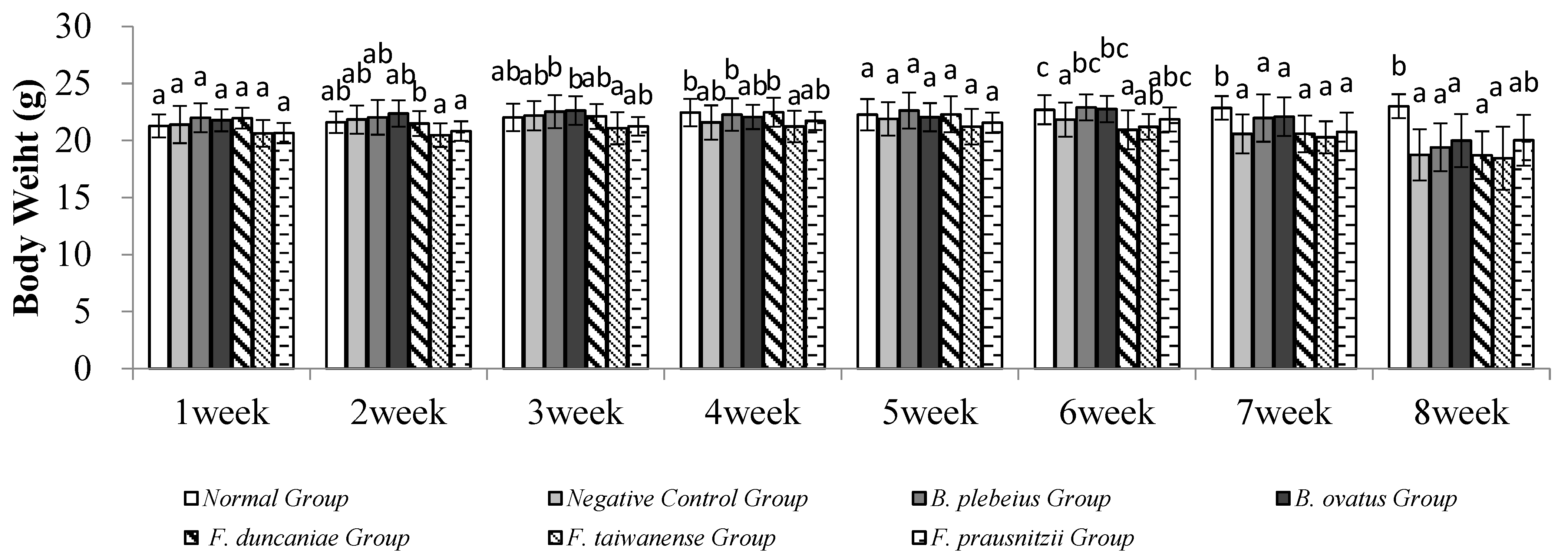

2.1. Body Weight Change

No animals died during the experiment. There was no significant difference in body weight among the groups in the first week (

p > 0.05). In the second week, the body weight of the

B. ovatus group was significantly higher than those of the

F. taiwanense and

F. prausnitzii groups (

p < 0.05). In the third week, the body weights of the

B. plebeius and

B. ovatus groups were significantly higher than that of the

F. prausnitzii group (

p < 0.05). In the fourth week, the body weights of the normal group and the

B. plebeius group were significantly higher than that of the

F. taiwanense group (

p < 0.05). There was no significant difference among the groups in the fifth week. In the sixth to eighth weeks, the body weight of the normal group was significantly higher than those of the other groups (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 1).

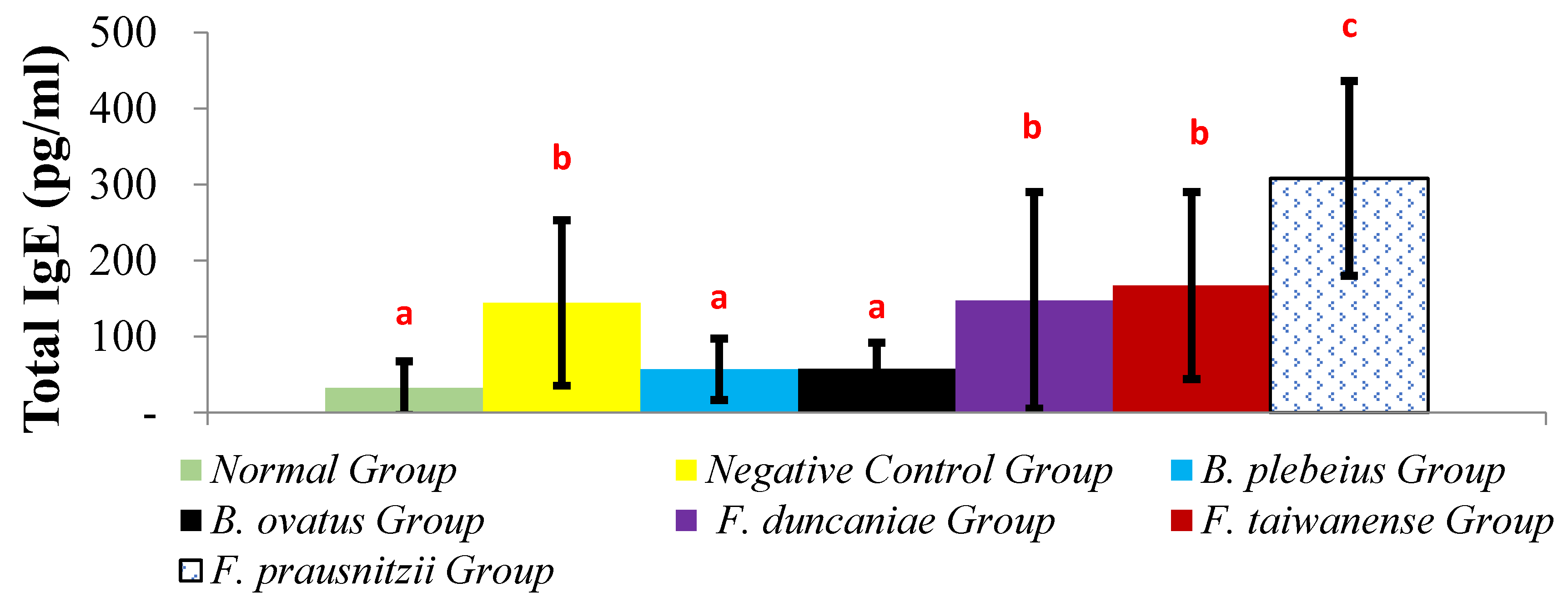

2.2. Total Serum IgE

The serum IgE levels in the

B. plebeius and

B. ovatus groups were 57.01 ± 40.36 pg/mL and 57.75 ± 34.40 pg/mL, respectively, which were significantly lower than that in the negative control group. The

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii group serum IgE levels were 147.56 ± 142.51, 167.24 ± 122.97, and 308.18 ± 128.24 pg/mL, respectively. Except for the

F. prausnitzii group, no other groups showed statistically significant differences from the negative control group. There was a significant difference between the oral

B. ovatus and

B. plebeius group (

p < 0.05) and the negative control group (

Figure 2).

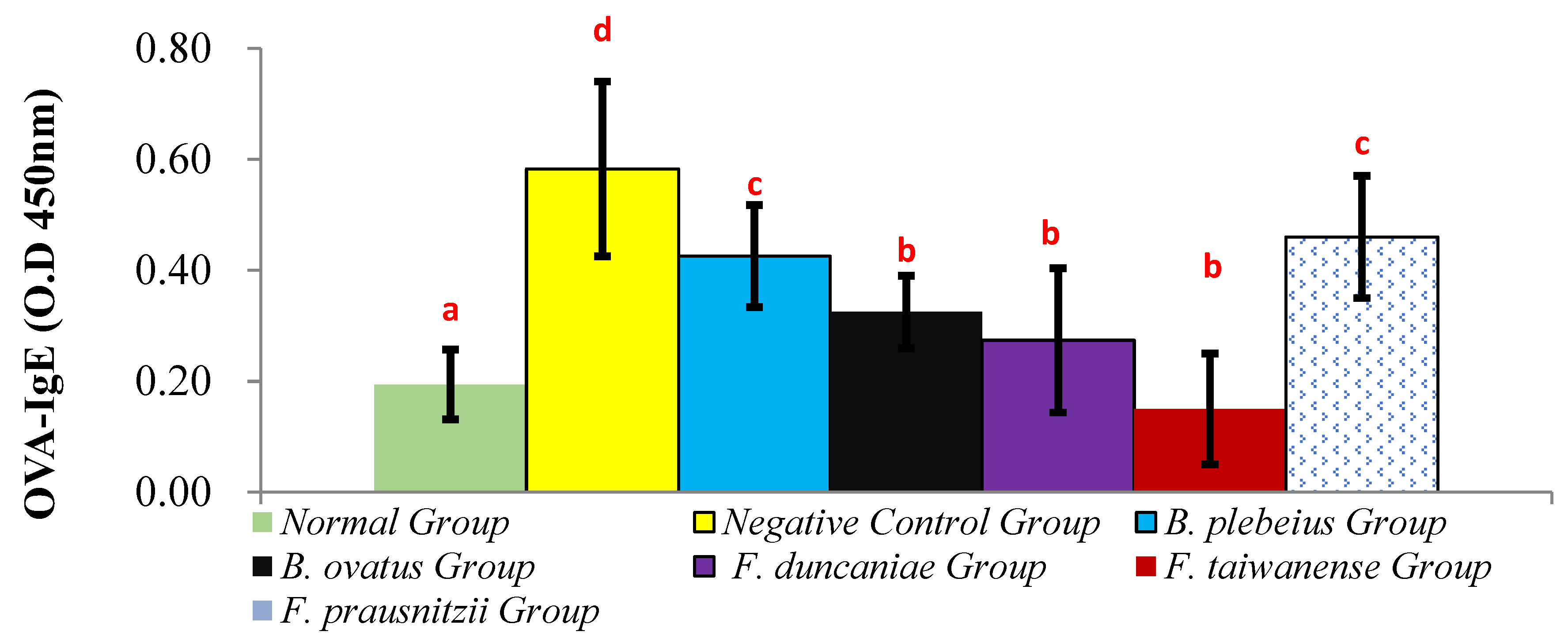

2.3. OVA-IgE Content in Serum

The expression levels of OVA-IgE in the serum of the normal group and the negative control group were 0.19 ± 0.06 and 0.58 ± 0.16, respectively, and the expression level of OVA-IgE in the normal group was significantly lower than that in the negative control group (

p < 0.001). In addition, the serum levels of OVA-IgE in the

B. plebeiu,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii groups were 0.43 ± 0.09, 0.33 ± 0.07, 0.27 ± 0.13, 0.15 ± 0.10, and 0.46 ± 0.11, respectively. The OVA-IgE expression of the

B. plebeiu,

F. prausnitzii,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae, and

F. taiwanense treatments displayed a downward trend from the negative control value (

Figure 3).

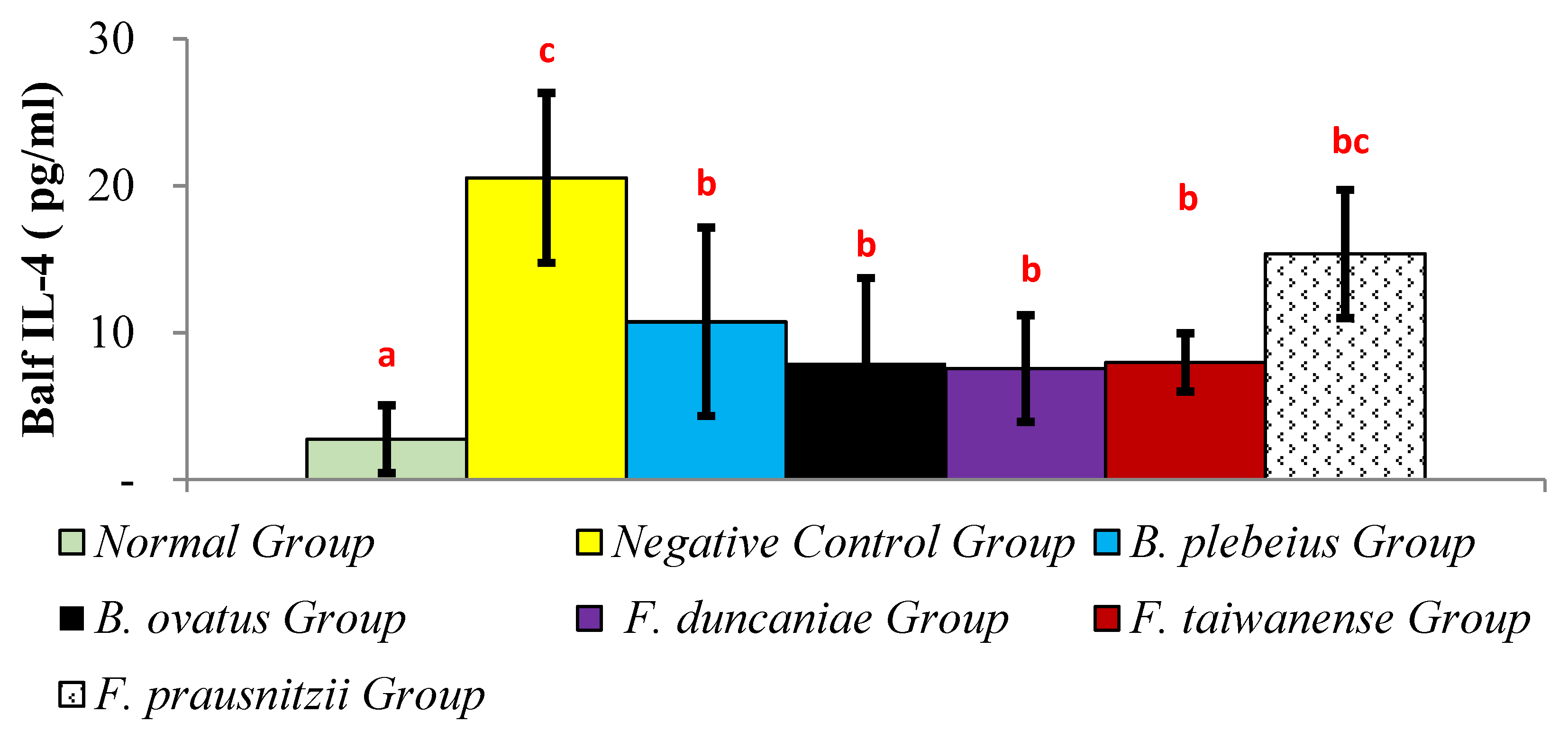

2.4. Expression of IL-4 in Alveolar Flushing Fluid

The level of IL-4 in the alveolar lavage fluid of the normal group was significantly lower than that in the negative control group (2.75 ± 2.31 pg/mL vs. 20.54 ± 5.78 pg/mL;

p < 0.05). In addition, the IL-4 levels in the alveolar lavage fluid of the

B. plebeius,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii groups were 10.74 ± 6.41, 7.92 ± 5.79, 7.56 ± 3.63, 7.98 ± 1.98, and 15.36 ± 4.36 pg/mL, respectively, all of which were significantly lower than those in the negative control group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 4).

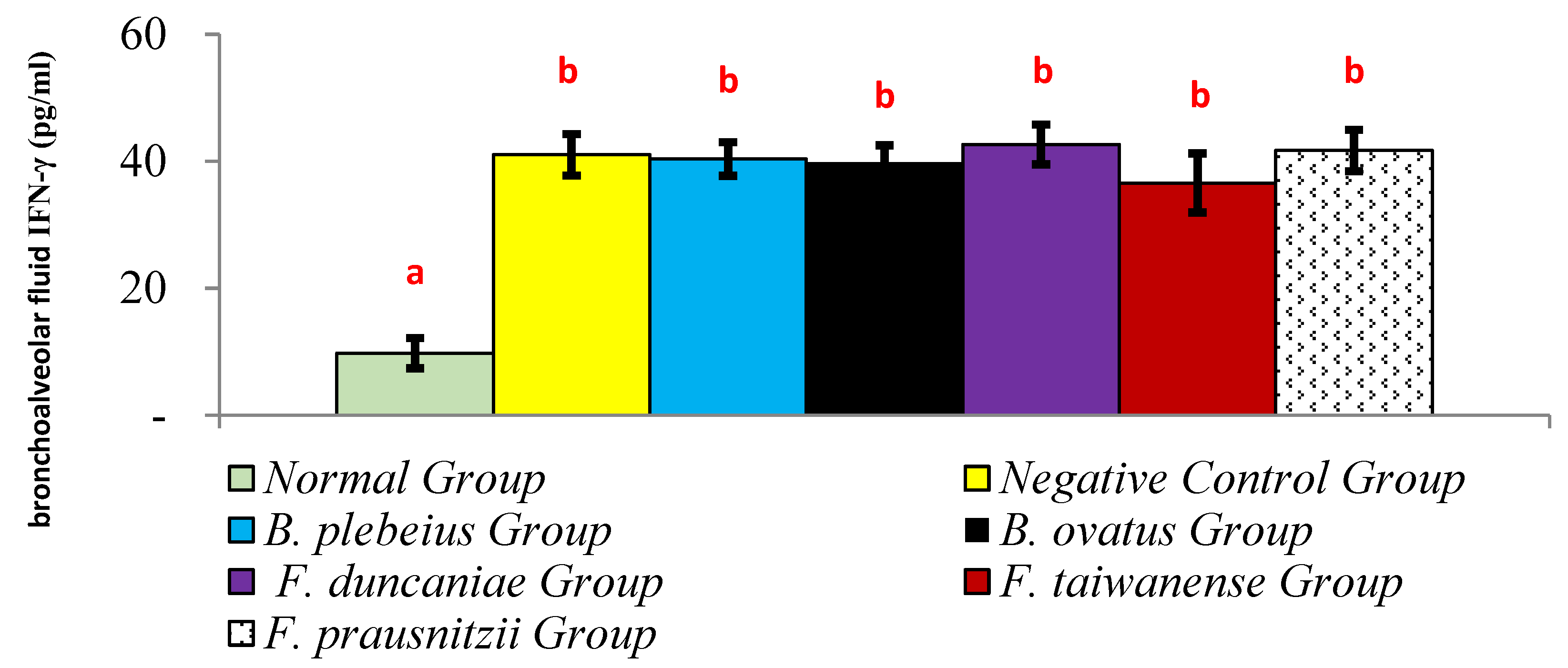

2.5. Expression of IFN-γ in Alveolar Flushing Fluid

The level of IFN-γ in the alveolar flushing fluid in the normal group was significantly lower than that in the negative control group (9.77 ± 2.39 pg/mL vs. 41.02 ± 3.26 pg/mL;

p < 0.05). In addition, the levels of IFN-γ in the alveolar washing fluid of the

B. plebeiu,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii groups were 40.35 ± 2.66, 39.84 ± 2.69, 42.65 ± 3.13, 36.58 ± 4.65, and 41.69 ± 3.26 pg/mL, respectively, and there was no significant difference compared with the negative control group (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 5).

The results showed that, except for Group F, all probiotic groups exhibited a significant decrease in IL-4 compared with the negative control group. IL-4 primarily acts through the Th2 pathway, as it can drive and induce Th2 helper cells, whose main function is to mediate immune responses against extracellular multicellular parasites. It is therefore not strictly necessary to measure the number and activity of Th2 cells in order to demonstrate that these immune responses are related to Th2.

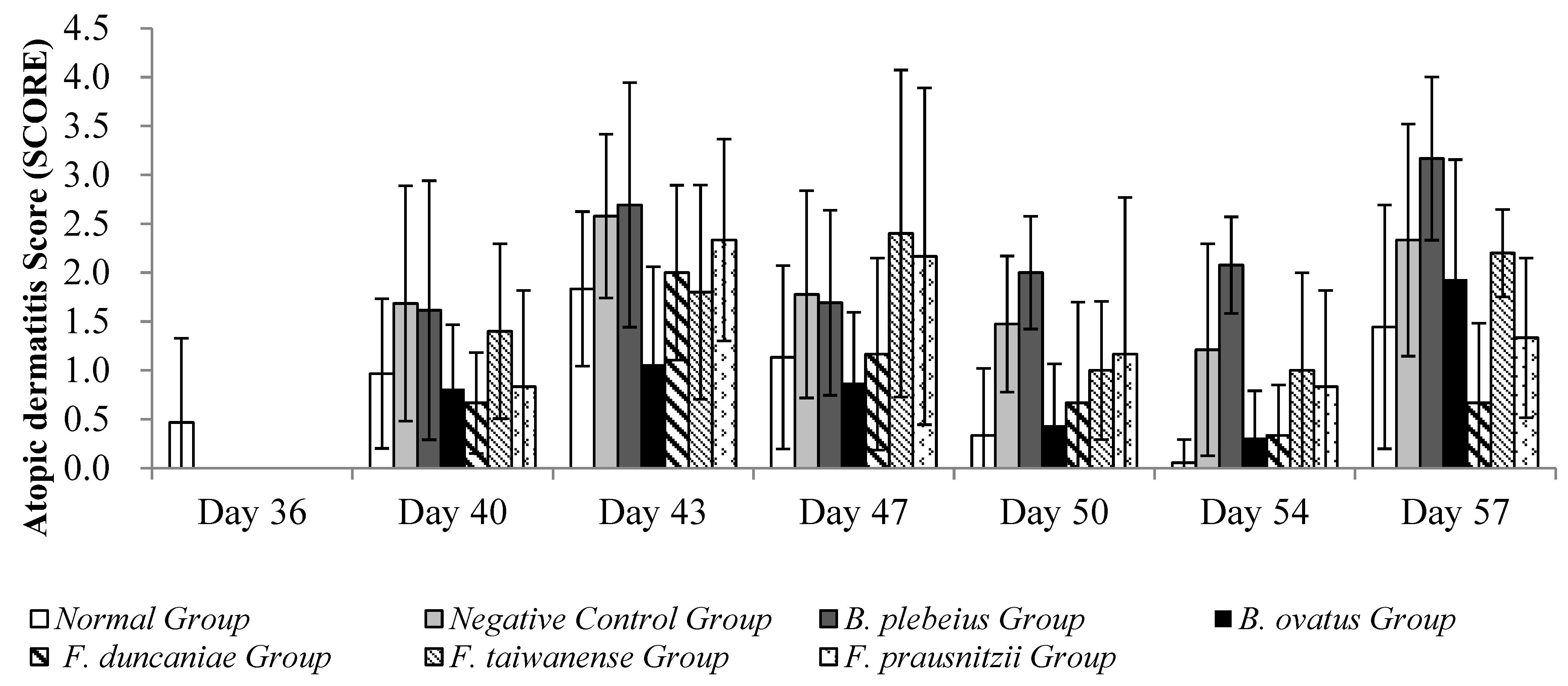

2.6. Skin Condition Observation

The observation results of the skin condition of each group in the stimulation-induced AD animal model with OVA are summarized in

Figure 6. During the induction period, observations and recordings were made once at intervals of 3 to 4 days, and skin stimulation was performed twice in total. During the first skin stimulation period (days 40~43), the average AD score examination at the stimulation site in the negative control group was significantly higher than that of the normal group (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 6). Compared with the negative control group, the average skin SCORE in the

B. ovatus group was significantly lower (

p < 0.05), while the average skin SCORE in the

B. plebeius group was lower but without significance (

p > 0.05).

When the animals were unwrapped and not in contact with the allergen (OVA), the skin condition of the animals in each group gradually returned to normal. On days 47 and 50, the average SCORE of the stimulated skin were 1.3 and 0.5 in the normal group; 2.5 and 1.8 in the negative control group; 0.88 and 0.44 in the B. plebeius group; and1.17 and 0.67 in the F. duncaniae group. The average skin SCORE in the negative control group was significantly higher than the scores in the normal group and B. ovatus group (p < 0.05), while the average score in the B. ovatus group was close to that of the normal group.

During the second skin stimulation induction with OVA (days 54 and 57), the severity of dermatitis in the control group was lower than that of the first stimulation induction, and the recovery time was shortened. The B. ovatus and F. duncaniae group scores were 0.31, 1.93 and 0.33, 0.67, respectively. In addition, the average scores in the negative control group were higher than those in the other groups, and there was a significant difference with the normal group (p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

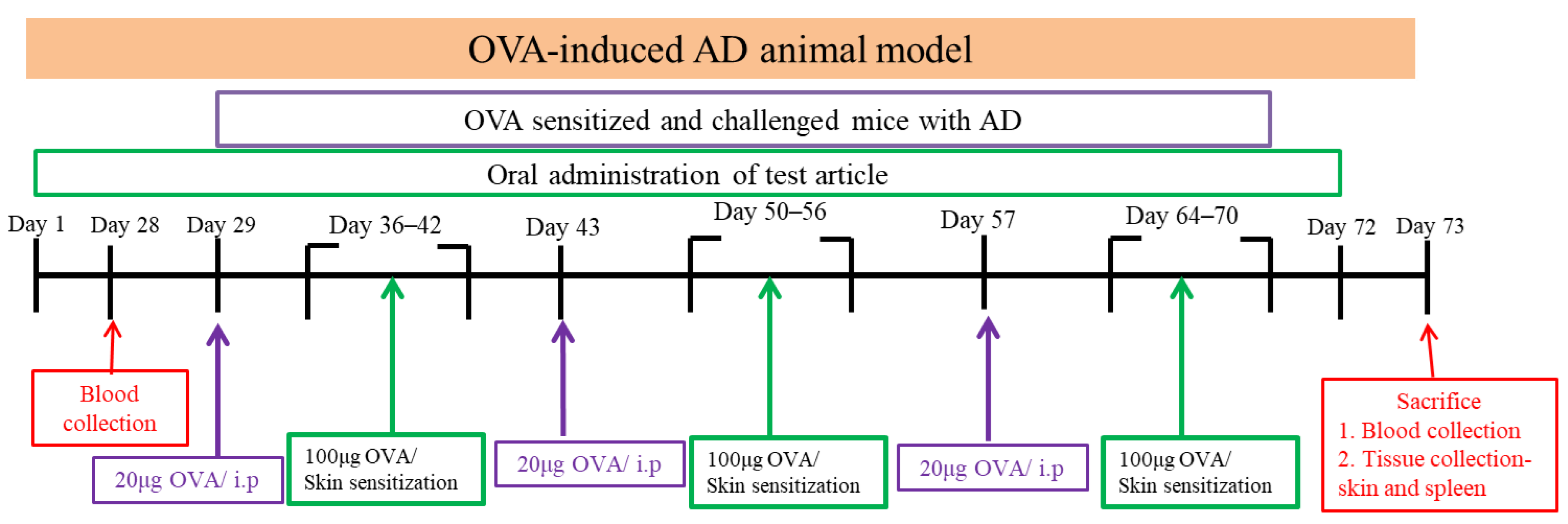

This study presents an interesting and unique approach to understanding the role of probiotics in AD and the development of AD. Not many studies have utilized this specific investigation method, which combines oral probiotic administration with OVA skin stimulation to create a model that mirrors the progression of AD to asthma. In this study, the AD model was induced by OVA skin stimulation following 4 weeks of oral administration of probiotics (B. plebeius, B. ovatus, F. duncaniae, F. taiwanense, and F. prausnitzii) and OVA. The oral route of administration was chosen to simulate the most common mode of probiotic intake in humans. OVA was selected, as it is widely recognized in immunological research as a standard immunogen capable of inducing robust antigen-specific immune responses in animal models; this aligns with the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis, which is closely linked to allergic immune reactions against environmental antigens. Furthermore, AD is closely associated with other allergic diseases and is considered the initial step of the so-called “atopic march,” with nearly 80% of patients subsequently developing asthma or allergic rhinitis. During the final 3 days of the test, a 3% OVA aerosol was administered to induce the asthma model. The expression of IgE in the serum, cytokine levels in the lung lavage fluid, and the condition of the skin at the stimulation site were then evaluated.

When an allergic reaction occurred, Th2 cells secreted IL-4, which increased the concentration of IgE antibodies in the serum. Our findings are similar to those of a previous study, in which the linear discriminant analysis effect size indicated that Bacteroidaceae and Porphyromonadaceae could act as possible biomarkers associated with the diagnosis of AD. Probiotics can modify the composition of the gut microbiome, which may have an impact on the incidence and development AD. Thus, it can be concluded that the development of AD is significantly influenced by gut microbiota [

8].

AD is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disease, whose pathogenesis has not been fully understood. Although some AD mouse models already exist, it is not easy to establish a model that can represent the natural development of human AD [

10]. In this study, we developed an AD model based on the inside–outside theory and investigated the effects of

B. plebeius,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii. Probiotics have been considered immunomodulators in allergic diseases. The AD model resulted in skin erythema and itching and increased skin inflammation, as assessed by mouse skin scoring. Oral administration of

F. duncaniae and

F. prausnitzii alleviated all the disease parameters mentioned above. In the AD model, OVA-specific IgE and total IgE were expressed, but these expressions were reduced in the AD mice treated with

B. plebeius,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae, and

F. taiwanense. According to Asahi data, atopic manifestations occur in a series, usually with AD in infancy and allergic rhinitis and/or asthma later in life. In this study, 3% OVA was administered into the trachea after the experiment to induce asthma. The late-stage atopic dermatitis–asthmatic pattern is defined as immune dysregulation driven by Th2 cells, characterized by elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and IL-5 [

9]. Administration of

B. plebeius,

B. ovatus,

F. duncaniae,

F. taiwanense, and

F. prausnitzii significantly reduced the level of IL-4 in lung lavage fluid.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study reveal that probiotics, particularly B. plebeius, B. ovatus, F. duncaniae, and F. taiwanense, play an important role in alleviating symptoms of AD, including skin erythema, itching, and inflammation, as shown by improved mouse AD skin scoring. Additionally, these probiotics have been shown to reduce levels of OVA-specific IgE and total IgE, which are key markers of allergic reactions. This study also demonstrated that the immunopathophysiology of asthma and atopic dermatitis is heterogeneous, and not all patients exhibit Th2-driven inflammation. Likewise, IgE-dependent sensitization is not an obligatory requirement for the development of these diseases. We have revised the relevant statements in the manuscript to reflect this more nuanced understanding, citing the recent literature that highlights endotypic diversity in both asthma and atopic dermatitis. Notably, treatment with these probiotics led to a reduction in IL-4 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. These findings suggest that probiotic intervention can attenuate allergic immune responses, thereby improving both AD and its progression to asthma, and may offer a promising therapeutic strategy for managing allergic diseases.