Gepirone for Major Depressive Disorder: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Evidence: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

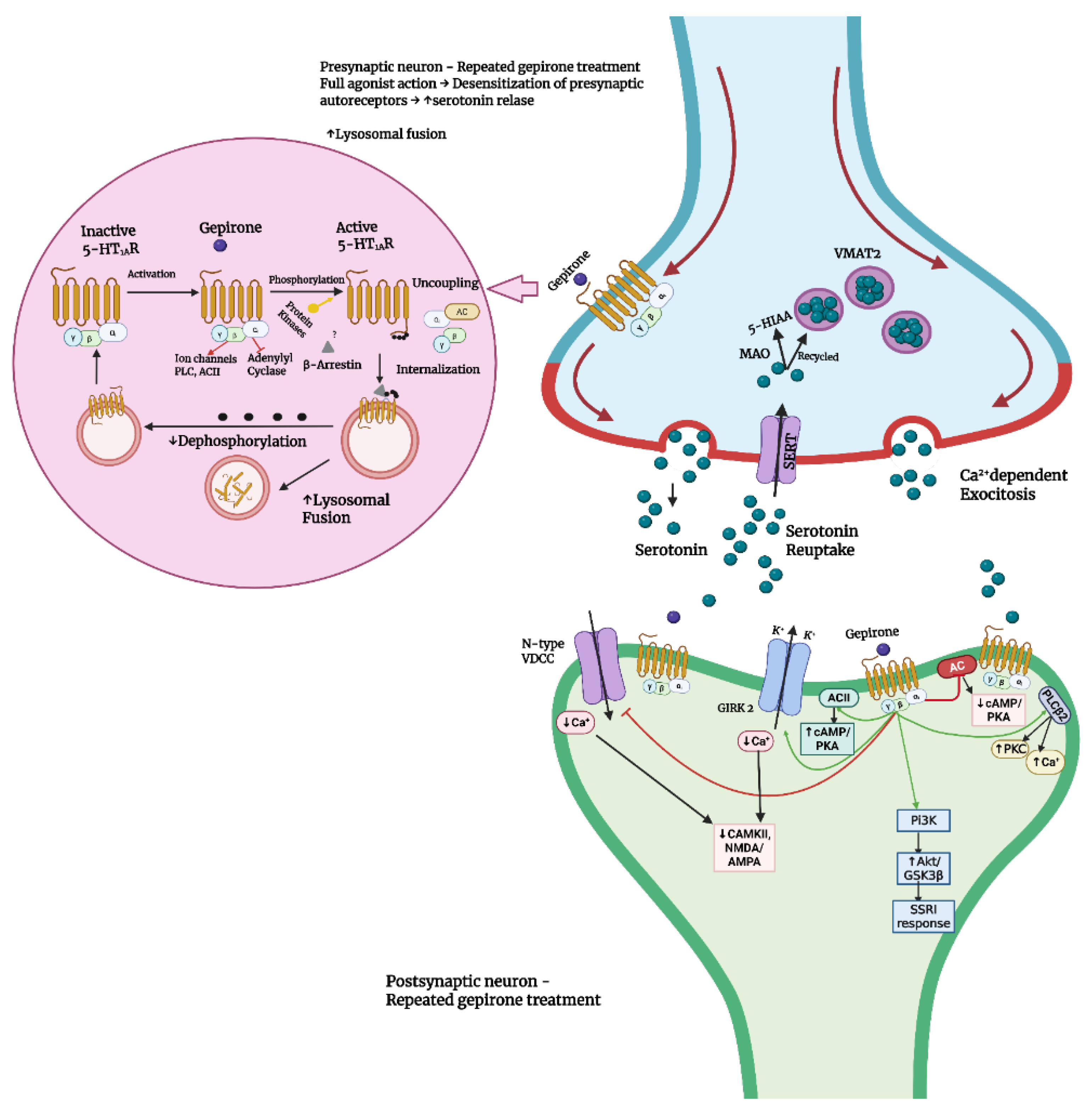

2. Pharmacology

2.1. Pharmacodynamics

2.2. Pharmacokinetics

2.2.1. Absorption

2.2.2. Distribution

2.2.3. Metabolism

2.2.4. Excretion

3. Preclinical Development of Gepirone

3.1. Electrophysiological Studies

3.2. Behavioral Studies

3.2.1. Anti-Aggressive Properties of Gepirone

3.2.2. Anxiolytic-like Properties of Gepirone

3.2.3. Antidepressant-like Properties of Gepirone

| Study | Species/Strain | Model/Treatment | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| McMillen et al. (1987) [53] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | In vivo recording of single cell impulse flow–dopamine cells

|

|

In vivo recording of single cell impulse flow–serotonin cells

|

| ||

| McMillen et al. (1987) [53] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

Affinity for dopamine and serotonin receptors (IC50)

|

|

| Blier and de Montigny (1987) [54] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

| Gepirone alone:

↑ED50 Gepirone (14 days + 48 h/15 mg/kg) + LSD: ↑ED50 Gepirone 14 days/15 mg/kg per day: ↓Responsivenes of 5HT neurons to 5-HT, LSD, 8-OH-DPAT and gepirone ↔Responsivenes of 5HT neurons to GABA ↔Firing activity by 8-OH-DPAT ↓Firing activity by gepirone and 8-OH-DPAT in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons. Effectiveness in dorsal hippocamus and dorsal raphne: ↑Effectiveness in raphne 5HT neurons than hippocampal pyramidal neurons (gepirone and 8-OH-DPAT ↑Effectiveness in hippocampus than in raphne (5-HT) ↔Effectiveness after gepirone treatment for 14 days/15 mg/kg per day Geprione effect on synaptic transmission: ↔Synaptic transmission (acute/10–50 μg/kg) ↔Synaptic transmission (14 days/15 mg/kg per day) |

| McMillen et al. (1989) [55] | Male CD-1 mice | Intraspecies aggression induced by isolation

| Gepirone alone: ↓Number of fighting (dose-dependent; 1/8 at 10 mg/kg) ↔Time on rotating rod (5–10 mg/kg) mCPP alone: ↓Number of fighting (dose-dependent; 1/8 at 10 mg/kg) ↓Time on rotating rod (5–10 mg/kg) TFMPP alone: ↓Number of fighting (1/8 at 5 mg/kg; total inhibition at 10 mg/kg) ↓Time on rotating rod (similar to mCPP) 8-OH-DPAT alone: ↓Number of fighting (dose-dependent; total inhibition at 2 mg/kg) ↔Time on rotating rod (1 mg/kg) Gepirone + Methiothepin/Methysergide: ↓Number of fighting (more potent; total inhibition at 5 mg/kg) ↔Time on rotating rod (Methysergide; Gepirone at 5 mg/kg) ↓Time on rotating rod (Methiothepin; Gepirone at 5 mg/kg) Methiothepin/Methysergide alone: ↔Number of fighting ↔Time on rotating rod mCPP + Methiothepin/Methysergide: ↓Number of fighting (no change from mCPP alone) ↔Time on rotating rod (Methysergide; mCPP at 5 mg/kg) ↓Time on rotating rod (Methiothepin; mCPP at 5 mg/kg) 8-OH-DPAT + Methysergide: ↓Number of fighting (more potent; total inhibition at 1 mg/kg) ↔Time on rotating rod (Methysergide; 8-OH-DPAT at 1 mg/kg) ↓Time on rotating rod (Methiothepin; 8-OH-DPAT at 1 mg/kg) 1-PP alone: ↓Number of fighting (4/8 at 10 mg/kg) SKF 525A + Gepirone (5 mg/kg): ↓Number of fighting (more potent; total inhibition) |

| McMillen et al. (1987) [55] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Monoamine metabolism (DOPAC/HVA/5HIAA)

| Gepirone-Striatum: ↔HVA conc. (0.5 mg/kg) ↓HVA conc. (1.25–2.5 mg/kg) ↑HVA conc. (5 mg/kg) ↔DOPAC conc. (0.5–1.25 mg/kg) ↑DOPAC conc. (2.5–5 mg/kg) ↔5HIAA conc. (0.5–1.25 mg/kg) ↓5HIAA conc. (2.5–5 mg/kg) Gepirone–prefrontal cortex: ↔HVA conc. ↔DOPAC conc. ↔5HIAA conc. |

| Lopez-Mendoza et al. (1998) [56] | Male BALB/C mice | Territorial aggression inducted by isolation

| Gepirone alone: ↓ Latency of attack ↓Attack frequency ↓Tail rattling ↔Grooming ↔Motor impairment ↑Exploratory sniffing ↑Social sniffing (2.5 and 7.5 mg/kg) WAY 100653 alone: ↔ Latency of attack ↔Attack frequency ↔Tail rattlin ↔Motor impairment ↔Exploratory sniffing ↔Social sniffing ↑Grooming Gepirone + WAY 100653: ↓ Latency of attack ↑Attack frequency ↑Tail rattling ↔Grooming ↔Motor impairment ↔Exploratory sniffing ↔Social sniffing |

| Lopez-Mendoza et al. (1998) [56] | Male BALB/C mice | Elevated plus-maze

| Gepirone alone: ↔Open and closed arms entries ↑Time spent in open arms (7.5 mg/kg) ↓Protected head dips (7.5 mg/kg) ↓Protected stretches (7.5 mg/kg) ↓Returning into closed arms from center platform WAY 100635 alone: ↔Open and closed arms entries ↑Time spent in open arms (5 mg/kg) ↓Protected head dips (5 mg/kg) ↔Protected stretches ↔Returning into closed arms from center platform Gepirone + WAY 100635: ↓Open and closed arms entries (7.5 mg/kg Gepirone vs. 7.5 mg/kg Gepirone + WAY 100635) ↓Time spent in open arms (compared to Gepirone alone) ↑ Protected head dips (7.5 mg/kg Gepirone vs. 7.5 mg/kg Gepirone + WAY 100635) ↓ Protected head dips (2.5 mg/kg Gepirone + 5 mg/kg WAY 100635) ↑ Protected stretches (7.5 mg/kg Gepirone vs. 7.5 mg/kg Gepirone + WAY 100635) ↔Returning into closed arms from center platform–exception: ↑Returning (7.5 mg/kg Gepirone vs. 7.5 mg/kg Gepirone + 1.5 mg/kg WAY 100635) |

| Bonson et al. (1994) [57] | Male Fischer rats | Androgen-induced dominance

| Gepirone/Buspirone/8-OH-DPAT: ↓Dominant effect (in testosterone-treated rats)-dose dependent ↑Flattened body posture (10 mg/kg) ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treted rats) ↑ Dominant effect (Gepirone 10 mg/kg; pretreated with Pizotyline/Pirenperone/Pindolol and 8-OH-DPAT 1 mg/kg pretreated with Pindolol) ↔Dominant effect (Buspirone 10 mg/kg pretreated with Pizotyline/Pirenperone/Pindolol and 8-OH-DPAT 1 mg/kg pretreated with Pizotyline/Pirenperone) Eltroprazine: ↓Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats)–dose dependent ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treated rats) ↔Dominant effect (6 mg/kg pretreated with Pizotyline/Pirenperone/Pindolol) TFMPP: ↓Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats) ↑Hindleg abduction (8 mg/kg) ↑Purposless chewing (8 mg/kg) ↑Hallucinogenics pause (8 mg/kg) ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treated rats) DOM: ↓Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats) ↑Head shakes and contraction of back muscles (6 mg/kg) ↑Purposless chewing (6 mg/kg) ↑Hallucinogenics pause (6 mg/kg) ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treated rats) Chlordiazepoxide: ↔Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats at 3 and 10 mg/kg) ↓Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats at 20 mg/kg)–lack of motor ability to move ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treated rats) Morphine: ↓Dominant effect (in Testosterone treated rats at 6 mg/kg) ↔Dominant effect (in non-testosterone treated rats) ↔Dominant effect (6 mg/kg pretreated with Pizotyline/Pindolol) ↑Dominant effect (6 mg/kg pretreated with Pirenperone) |

| Costello et al. (1991) [58] | Female Long-Evans rats | Conditioned suppression of drinking

| Predictable schedule:

|

| Yamashita et al. (1995) [59] | Male Wistar rats | Drinking conflict test

|

|

| Eison et al. (1986) [60] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Drinking conflict test

| Gepirone (non-lesioned rats): ↑Liking (38-fold) Buspirone (non-lesioned rats): ↑Licking (5-fold) Diazepam (non-lesioned rats): ↑Liking (19-fold) Gepirone (lesioned rats): ↔Licking (compared to control) Buspirone (lesioned rats): ↔Licking (compared to control) Diazepam (lesioned rats): ↔Licking (compared to control) |

| Eison et al. (1986) [60] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Serotonin syndrome

| Gepirone:

↓Tremor ↓Straub tail ↓Muscular hypertonus ↓Treading ↓Hindlimb abduction ↓Lateral head waving |

| Eison et al. (1986) [60] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Acoustic startle test

| Non-lesioned rats:

|

| Kehne et al. (1988) [61] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Potentiated startle testing

| Gepirone: ↔Startle amplitude in Noise-Alone trial ↓Startle amplitude in Light-Noise trial (5 and 10 mg/kg) Gepirone was less potent than Buspirone Buspirone: ↔Startle amplitude in Noise-Alone trial ↓ Startle amplitude in Light-Noise trial (1.25-5 mg/kg) 1-PP: ↔ Startle amplitude in Light-Noise trial |

| Söderpalm et al. (1989) [62] | Male Sprague-Dowley rats | Elevated lus maze test/Montgomery’s conflict test

| Gepirone: ↑ Open arms entries (32 nmol/kg) ↑Time spent in open arms (32–128 nmol/kg) ↓Time spent in open arms (2048 nmol/kg) ↔Total number of entries (8–512 nmol/kg) ↓ Total number of entries (2048 nmol/kg) Buspirone: ↑ Open arms entries + time spent in open arms (32–128 nmol/kg) ↓ Open arms entries + time spent in open arms (2048 nmol/kg) ↑ Total number of entries (8 nmol/kg) ↔ Total number of entries (32–512 nmol/kg) ↓ Total number of entries (2048 nmol/kg) Ipsapirone: ↑ Open arms entries (32 nmol/kg) ↑Time spent in open arms (32–512 nmol/kg) PMP: ↓ Open arms entries time spent in open arms (32 and 512 nmol/kg) ↔ Total number of entries (8–512 nmol/kg) ↓ Total number of entries (2048 nmol/kg) 8-OH-DPAT: ↑ Open arms entries + time spent in open arms (100–200 nmol/kg) ↔Total number of entries (50–200 nmol/kg) ↓ Total number of entries (400 nmol/kg) L-5-HTP + Benserazide: ↑ Open arms entries (56 μmol/kg L-5-HTP) ↓ Open arms entries + time spent in open arms (448 μmol/kg L-5-HTP) ↔ Total number of entries (28–112 and 448 μmol/kg L-5-HTP) ↑ Total number of entries (224 μmol/kg L-5-HTP) |

| Motta et al. (1992) [63] | Male Wistar rats | Plus-maze test

| Gepirone:

↓Open arms entries (1 mg/kg) ↓Time spent in open arms Prazosin: ↔Open arms entries ↔Time spent in open arms |

| Silva and Brandão (2000) [64] | Male Wistar rats | Elevated Plus-maze

| Acute treatment—Gepirone: ↑Grooming ↑Flat-back approach ↑Immobility ↔Open arms entries; ↔Center platform entries; ↔Enclose arms entries; ↔Peeping out ↔Sap ↓Time spent in open arms; ↓Rearing ↓Scanning ↓Head dipping ↓End arm activity Chronic treatment—Gepirone: ↑Open arms entries ↑Time spent in open arms ↑Time spent in close arms ↑Head dipping ↑End-arm activity ↔Peeping out ↔Grooming ↔Rearing ↔Scanning ↔Sap ↓Flat back approach ↓Immobility Acute treatment—Fluoxetine: ↑Enclosed arms entries ↔Peeping out ↔Grooming ↔Rearing ↔Scanning ↔Flat-back approach ↔Stretched-attend posture ↔Immobility ↓Open arms entries ↓Time spent in open arms ↓Time spent in center platform ↓Head dipping ↓End-arm activity Chronic treatment—Fluoxetine: ↔Open arm entries ↔Time spent in center platform ↔Time spent in open arms ↔Peeping out ↔Grooming ↔Rearing ↔Scanning ↔Flat-back approach ↔Head dipping ↔Stretch-attend posture ↔End-arm activity ↔Immobility |

| Bodnoff et al. (1989) [65] | Male Long-Evans rats | Novelty-suppressed feeding

| Gepirone/Buspirone/Mianserin: ↔ Latency to began eating (acute) ↓ Latency to began eating (chronic) Diazepam: ↓ Latency to began eating (acute and chronic) Desipramine/Amitriptyline/Fluoxetine: ↑ Latency to began eating (acute) ↓ Latency to began eating (chronic) Nomifensine: ↑ Latency to began eating (acute) ↔ Latency to began eating (chronic) |

| De Vry et al. (1993) [66] | Male/Female Wistar rats | Shock-induced ultrasonic vocalization

| Dose dependent complete reduction in ultrasonic vocalization in i.p. administration. Dose dependent almost complete (95%) reduction of ultrasonic vocalization in p.o. administration. |

| Przegaliński et al. (1990) [67] | Male Wistar rats | Forced swimming test + open field test

| Gepirone alone: ↓Immobility time (acute and repeated treatment). ↓Ambulation (20 mg/kg) ↓Rearing Gepirone (5 and 10 mg/kg) + Proadifen: ↓Immobility time (more potent) Buspirone, Ipsapirone, 1-PP: ↔ Immobility time (acute and repeated treatment)

↔Immobility time |

| Chojnacka-Wójcik et al. (1991) [68] | Male Wistar rats | Forced swimming test

| Gepirone alone: ↓Immobility time (dose-dependent) Gepirone + Metergoline: ↓Immobility time Gepione + Ketanserin: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + Prazosin: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + Betaxolol: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + ICI 119,551: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + PCA: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + PCPA: ↓Immobility time Gepirone + NAN-190 ↔Immobility time Gepirone + Pindolol: ↔Immobility time Gepirone + Spiperone: ↔Immobility time Gepirone + Haloperidol: ↔Immobility time |

| Benvenga and Leander (1993) [69] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Forced swim test

| Gepirone: ↔Immobility time (5–10 mg/kg); ↓Immobility time (20 mg/kg). Impiramine: ↔Immobility time (5–20 mg/kg); ↓Immobility time (40 mg/kg); ↑Sedation (20–40 mg/kg); 8-OH-DPAT: ↑Immobility time (0.32 mg/kg); ↔Immobility time (0.16 and 0.64 mg/kg); ↓Immobility time (1.25 mg/kg). LY228729: ↔Immobility time (0.3 mg/kg); ↓Immobility time (1–3 mg/kg); ↑Frequency of flat body posture (1–3 mg/kg; short duration, only on first day of testing); ↔Locomotor activity. |

| Giral et al. (1988) [70] | Male Wistar AF rats | Inescapable footshock

| Gepirone: ↓Escape failures 8-OH-DPAT: ↓Escape failures Buspirone: ↓Escape failures TVXQ 7821: ↓;Escape failures |

| Drugan et al. (1987) [71] | Male Sprague-Dawley rats | Inescapable shock in two-way shuttle-box

| Gepirone: ↔Latency to escape response Buspirone: ↔Latency to escape response (2 mg/kg) ↓Latency to escape response (5 mg/kg) Chlordiazepoxide: ↓Latency to escape response |

| Camargo et al. (2008) [72] | Male Wistar rats | Inescapable footshock

| Gepirone: ↑Escape latencies (animals exposed on inescapable shock in comparison to non-exposed animals) ↑Escape latencies in well-nourished non-exposed rats (5 mg/kg) Chlodiazepoxide: ↑Escape latencies (animals exposed on inescapable shock in comparison to non-exposed animals) ↓Escape latency (5 and 7.5 mg/kg in comparison to saline) ↑Escape latency (malnourished animals in comparison to well-nourished animals) |

| Barrett et al. (1988) [73] | Male White Carneaux pigeons |

| ↑Responces in FI schedule (doses 0.03–3 mg/kg) ↑Responces in FR schedule (doeses 0.3 and 1 mg/kg) |

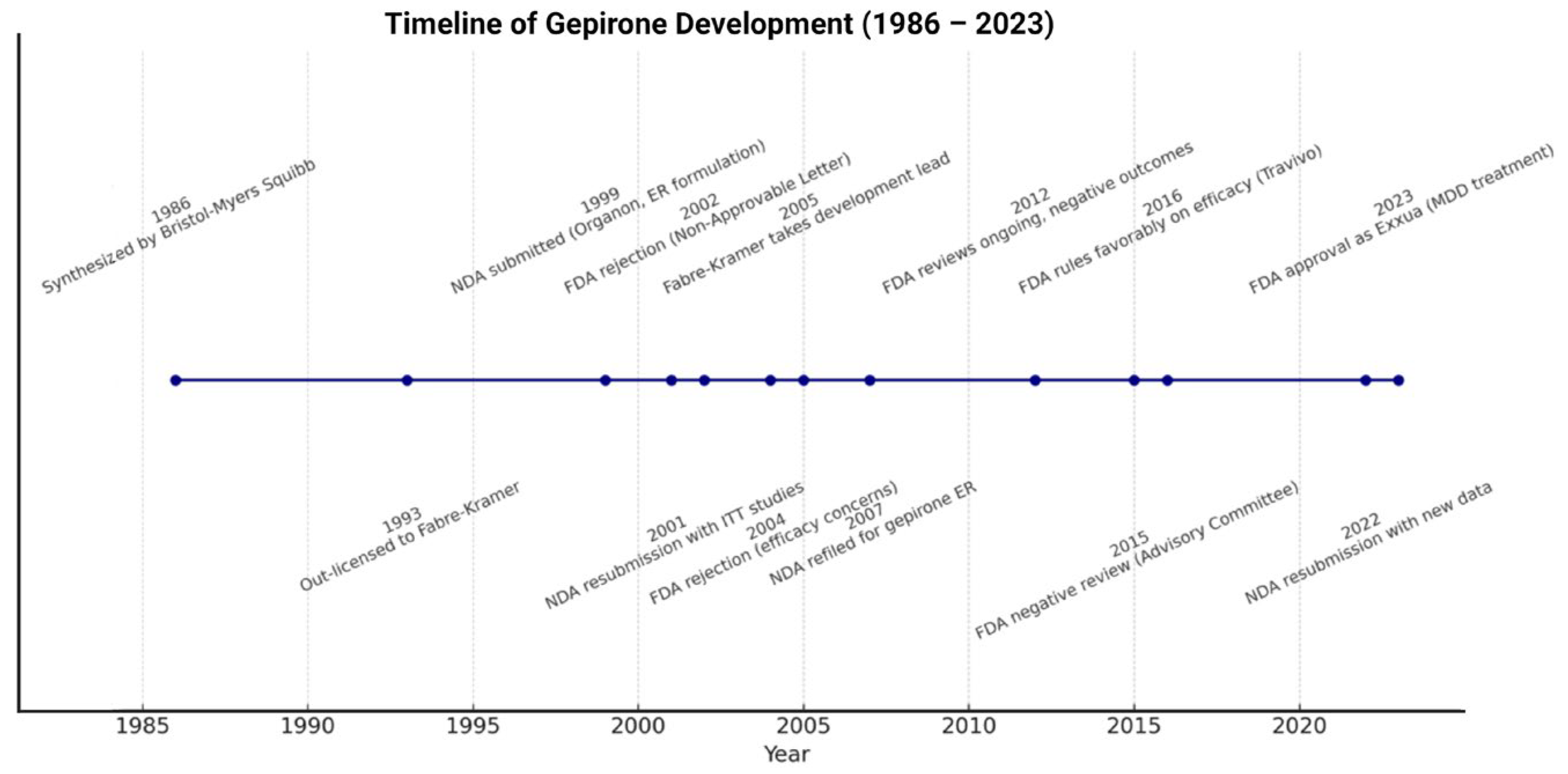

4. Clinical Development of Gepirone

5. Dosage, Safety, Drug Interactions and Adverse Effects of Gepirone ER

5.1. Dosage and Administration

5.2. Safety Considerations

5.3. Drug–Drug Interactions

5.4. Adverse Effects

6. Clinical Superiority of Gepirone over Other Azapirones

| Feature | Buspirone | Tandospirone | Perospirone | Gepirone ER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug class | Anxiolytic | Anxiolytic/antidepressant | Atypical antipsychotic | Antidepressant/anxiolytic |

| Primary indication | GAD | Anxiety, depression (Japan/China) | Schizophrenia; schizoaffective disorder | MDD (FDA-approved); anxiety |

| Receptor profile | 5-HT1A partial agonist; weak D2 antagonist | 5-HT1A partial agonist; minimal D2 activity | 5-HT1A partial agonist; D2 and 5-HT2A antagonist | Selective 5-HT1A agonist (full at presynaptic autoreceptors, partial at postsynaptic receptors) |

| Half-life | ~3 h | 2–3 h | ~1.9 h | ~6 h |

| Cmax | 1.01 ± 0.87 μg/L | 3 μg/L (30 mg dosage) | 8.8 ng/mL | 3.6–4.3 ng/mL |

| Tmax | 0.8 h | 0.5–2 h | 0.8 h | 4.8–5.6 h |

| AUC | 2.89 ± 3.40 h × μg/L | ~115 h × ng/mL | 22.0 h × ng/mL | 51.8–55.3 h × mg/mL |

| Metabolism | Mainly CYP3A4 | Mainly CYP3A4 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A4, CYP2D6; active metabolites (3′-OH-gepirone, 1-PP) |

| Pharmacokinetic limitations | Short half-life; multiple daily dosing | Short half-life; regional availability only | Very short half-life; antipsychotic-like PK (short half-life, need for frequent dosing, variable plasma levels) | stable plasma levels; avoids peaks/troughs |

| Major adverse effects | Dizziness, headache, limited antidepressant efficacy, mild dopaminergic side effects | Drowsiness, dizziness, rare extrapyramidal symptoms | Sedation, weight gain, extrapyramidal symptoms | Fewer dopaminergic side effects; lower rates of nausea and sexual dysfunction than SSRIs |

| Evidence base | Strong in GAD, weak in depression | Moderate efficacy in anxiety/depression; limited to Asia | Effective in schizophrenia; limited anxiolysis | Robust RCT evidence in MDD; relapse prevention; FDA approval (2023) |

7. Gepirone ER in Clinical Decision-Making: Practical Algorithm

- Inadequate response to SSRIs/SNRIs despite appropriate dose and duration.

- Intolerable side effects of first-line antidepressants, particularly sexual dysfunction, sedation, or sleep disturbances.

- Prominent anxiety symptoms accompanying MDD, where gepirone’s 5-HT1A partial agonism may provide added benefit.

- Patients at risk of benzodiazepine misuse, where gepirone represents a non-addictive anxiolytic alternative.

- Preference for simplified dosing, as the ER formulation allows once-daily administration.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: Hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhi, G.S.; Mann, J.J. Depression. Lancet 2018, 392, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Text Revised Version, 5th ed.; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroleo, M.; Carbone, E.A.; Primerano, A.; Foti, D.; Brunetti, A.; Segura-Garcia, C. The role of hormonal, metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers on sleep and appetite in drug-free patients with major depression: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 250, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliou, K.; Balaris, D.; Dokali, A.M.; Fotopoulos, V.; Kouletsos, A.; Katsiana, A. Exploring the effects of major depressive disorder on daily occupations and the impact of psychotherapy: A literature review. Cureus 2024, 16, e55831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. When biomarkers for major depressive disorder remain elusive. Med. Rev. 2024, 5, 177–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaro, M.; Anastasia, A.; Novello, S.; Fusco, A.; Pariano, R.; De Berardis, D.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Stubbs, B.; Vieta, E.; et al. The emergence of loss of efficacy during antidepressant drug treatment for major depressive disorder: An integrative review of evidence, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Pharmacol. Res. 2019, 139, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crescenzo, F.; De Giorgi, R.; Garriga, C.; Liu, Q.; Fazel, S.; Efthimiou, O.; Hippisley-Cox, J.; Cipriani, A. Real-world effects of antidepressants for depressive disorder in primary care: Population-based cohort study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2024, 226, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Manning, S.; Cutler, A.J. Good, better, best: Clinical scenarios for the use of L-methylfolate in patients with MDD. CNS Spectr. 2020, 25, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelek-Molik, A.; Litwa, E. Trends in research on novel antidepressant treatments. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1544795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowicz, K.; Sowa-Kućma, M. The treatment of depression—Searching for new ideas. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 988648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucido, M.J.; Dunlop, B.W. Emerging medications for treatment-resistant depression: A review with perspective on mechanisms and challenges. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkin, J.M.; Golani, L.K.; Smith, J.L. Clinical pharmacological innovation in the treatment of depression. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 16, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillen, B.A.; Mattiace, L.A. Comparative neuropharmacology of buspirone and MJ-13805, a potential anti-anxiety drug. J. Neural Transm. 1983, 57, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. Ligand Display: Gepirone. Available online: https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=12930 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Timmer, C.J.; Sitsen, J.M. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of gepirone immediate-release capsules and gepirone extended-release tablets in healthy volunteers. J. Pharm. Sci. 2003, 92, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, C.J.; Sitsen, J.M.A. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics and tolerability of gepirone extended-release. Clin. Drug Investig. 2002, 22, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam, J.D.; Brunswick, D.J.; Gibertini, M. Sustained efficacy of gepirone-IR in major depressive disorder: A double-blind placebo substitution trial. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2004, 38, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keam, S.J. Gepirone extended-release: First approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 1723–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBattista, C.; Schatzberg, A.F. The black book of psychotropic dosing and monitoring. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2024, 54, 8–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, F.Y.W.; Ereshefsky, L.; Port, A.; Timmer, C.J.; Dogterom, P. Effects of rifampin on the disposition of gepirone ER and its metabolites. Open Drug Metab. J. 2009, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keltner, N.L.; McAfee, K.M.; Taylor, C.L. Biological perspectives. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2002, 38, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijnzeel, D.; Yazdanpanah, M.; Suryadevara, U.; Tandon, R. Lurasidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: A critical evaluation. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2015, 16, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siafis, S.; Wu, H.; Wang, D.; Burschinski, A.; Nomura, N.; Takeuchi, H.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Davis, J.M.; Leucht, S. Antipsychotic dose, dopamine D2 receptor occupancy and extrapyramidal side-effects: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 3267–3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, A.; Andheria, M. A comparative multidose pharmacokinetic study of buspirone extended-release tablets with a reference immediate-release product. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2001, 41, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yang, J.; Yang, S.; Cao, S.; Qin, D.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Ye, Y.; Wu, J. Role of tandospirone, a 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist, in the treatment of central nervous system disorders and the underlying mechanisms. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 102705–102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, Y.; Shimizu, S.; Imaki, J. Effects of tandospirone, a 5-HT1A agonistic anxiolytic agent, on haloperidol-induced catalepsy and forebrain Fos expression in mice. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 109, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Tancredi, A.; Kleven, M.S. Comparative pharmacology of antipsychotics possessing combined dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor properties. Psychopharmacology 2011, 216, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurose, S.; Mimura, Y.; Uchida, H.; Takahata, K.; Kim, E.; Suzuki, T.; Mimura, M.; Takeuchi, H. Dissociation in Pharmacokinetic Attenuation Between Central Dopamine D2 Receptor Occupancy and Peripheral Blood Concentration of Antipsychotics: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2020, 81, 19r13113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals Inc. Gepirone ER: US Prescribing Information 2023. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Nadkarni, N.; Kim, P.; Shah, V. Exxua: A Lengthy Approval Under a Regulatory Lens. Pharmacy Times 2024. Available online: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/exxua-a-lengthy-approval-under-a-regulatory-lens (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Robinson, D.S.; Sitsen, J.M.A.; Gibertini, M. A review of the efficacy and tolerability of immediate-release and extended-release formulations of gepirone. Clin. Ther. 2003, 25, 1618–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yocca, F.D.; Eison, A.S.; Hyslop, D.K.; Ryan, E.; Taylor, D.P.; Gianutsos, G. Unique modulation of central 5-HT2 receptor binding sites and 5-HT2 receptor-mediated behavior by continuous gepirone treatment. Life Sci. 1991, 49, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Yang, P.C.; Zhang, Y.F.; Sun, J.F. Synthesis and clinical application of new drugs approved by FDA in 2023. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 265, 116124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celada, P.; Bortolozzi, A.; Artigas, F. Serotonin 5-HT1A receptors as targets for agents to treat psychiatric disorders: Rationale and current status of research. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, P.R.; Vahid-Ansari, F. The 5-HT1A receptor: Signaling to behavior. Biochimie 2019, 161, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślifirski, G.; Król, M.; Turło, J. 5-HT receptors and the development of new antidepressants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riad, M.; Garcia, S.; Watkins, K.C.; Jodoin, N.; Doucet, É.; Langlois, X.; El Mestikawy, S.; Hamon, M.; Descarries, L. Somatodendritic localization of 5-HT1A and preterminal axonal localization of 5-HT1B serotonin receptors in adult rat brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2000, 417, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitton, A.; Benfield, P. Gepirone in depression and anxiety disorders: An initial appraisal of its clinical potential. CNS Drugs 1994, 1, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluchowska, M.H.; Bugno, R.; Bojarski, A.J.; Charakchieva-Minol, S.; Duszyńska, B.; Tatarczyńska, E.; Kłodzińska, A.; Stachowicz, K.; Chojnacka-Wójcik, E. Novel, flexible, and conformationally defined analogs of gepirone: Synthesis and 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and D2 receptor activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, R.A. Gepirone. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2001, 2, 1120–1127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feiger, A.D.; Heiser, J.F.; Shrivastava, R.K.; Weiss, K.J.; Smith, W.T.; Sitsen, J.M.A.; Gibertini, M. Gepirone extended-release: New evidence for efficacy in the treatment of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, L.F.; Clayton, A.H.; Smith, L.C.; Goldstein, I.; Derogatis, L.R. The effect of gepirone-ER in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in depressed men. J. Sex. Med. 2012, 9, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commissaris, R.L. Conflict behaviors as animal models for the study of anxiety. In Techniques in the Behavioral and Neural Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; Volume 10, pp. 443–474. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre, L.F.; Timmer, C.J. Effects of food on the bioavailability of gepirone from extended-release tablets in humans: Results of two open-label crossover studies. Curr. Ther. Res. 2003, 64, 580–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, D.J.; Von Moltke, L.L.; Giancarlo, G.M.; Garteiz, D.A. Human cytochromes mediating gepirone biotransformation at low substrate concentrations. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2003, 24, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Exxua (Gepirone) Prescribing Information. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/021164s000lbl.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Deng, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, Z.; Fan, C.H.; Kwan, H.S.; Wong, C.H.; Shek, K.Y.; Zuo, Z.; Lam, T.N. A Review of Food-Drug Interactions on Oral Drug Absorption. Drugs 2017, 77, 1833–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, L.K.; Sciacca, M.A.; Sostrin, M.B.; Farmen, R.H.; Pittman, K.A. Effect of food on the bioavailability of gepirone in humans. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 33, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blier, P.; Ward, N.M. Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression? Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 53, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogterom, P.; Huisman, J.A.M.; Gellert, R.; Verhagen, A. Pharmacokinetics of gepirone in subjects with normal renal function and in patients with chronic renal dysfunction. Clin. Drug Investig. 2002, 22, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, B.A.; Scott, S.M.; Williams, H.L.; Sanghera, M.K. Effects of gepirone, an aryl-piperazine anxiolytic drug, on aggressive behavior and brain monoaminergic neurotransmission. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1987, 335, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blier, P.; de Montigny, C. Modification of 5-HT neuron properties by sustained administration of the 5-HT1A agonist gepirone: Electrophysiological studies in the rat brain. Synapse 1987, 1, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, B.A.; DaVanzo, E.A.; Song, A.H.; Scott, S.M.; Rodriguez, M.E. Effects of classical and atypical antipsychotic drugs on isolation-induced aggression in male mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1989, 160, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Mendoza, D.; Aguilar-Bravo, H.; Swanson, H.H. Combined effects of gepirone and (+)WAY 100135 on territorial aggression in mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1998, 61, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonson, K.R.; Johnson, R.G.; Fiorella, D.; Rabin, R.A.; Winter, J.C. Serotonergic control of androgen-induced dominance. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1994, 49, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, N.L.; Carlson, J.N.; Glick, S.D.; Bryda, M. Effects of acute administration of gepirone in rats trained on conflict schedules with different predictability. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1991, 40, 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Oishi, R.; Gomita, Y. Anticonflict effects of acute and chronic treatments with buspirone and gepirone in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1995, 50, 477–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eison, A.S.; Eison, M.S.; Stanley, M.; Riblet, L.A. Serotonergic mechanisms in the behavioral effects of buspirone and gepirone. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1986, 24, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kehne, J.H.; Cassella, J.V.; Davis, M. Anxiolytic effects of buspirone and gepirone in the fear-potentiated startle paradigm. Psychopharmacology 1988, 94, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderpalm, B.; Hjorth, S.; Engel, J.A. Effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists and L-5-HTP in Montgomery’s conflict test. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1989, 32, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motta, V.; Maisonnette, S.; Morato, S.; Castrechini, P.; Brandão, M.L. Effects of blockade of 5-HT2 receptors and activation of 5-HT1A receptors on exploratory activity of rats in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology 1992, 107, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.; Brandão, M.L. Acute and chronic effects of gepirone and fluoxetine in rats tested in the elevated plus-maze: An ethological analysis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000, 65, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnoff, S.R.; Suranyi-Cadotte, B.; Quirion, R.; Meaney, M.J. Comparison of diazepam and several antidepressants in an animal model of anxiety. Psychopharmacology 1989, 97, 277–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vry, J.; Benz, U.; Schreiber, R.; Traber, J. Shock-induced ultrasonic vocalization in young adult rats: A model for testing putative anti-anxiety drugs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 249, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przegaliński, E.; Tatarczyńska, E.; Chojnacka-Wójcik, E. Antidepressant-like activity of ipsapirone, buspirone and gepirone in the forced swimming test in rats pretreated with proadifen. J. Psychopharmacol. 1990, 4, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnacka-Wójcik, E.; Tatarczyńska, E.; Gołembiowska, K.; Przegaliński, E. Involvement of 5-HT1A receptors in the antidepressant-like activity of gepirone in the forced swimming test in rats. Neuropharmacology 1991, 30, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenga, M.J.; Leander, J.D. Antidepressant-like effect of LY228729 as measured in the rodent forced swim paradigm. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993, 239, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giral, P.; Martin, P.; Soubrié, P.; Simon, P. Reversal of helpless behavior in rats by putative 5-HT1A agonists. Biol. Psychiatry 1988, 23, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drugan, R.C.; Crawley, J.N.; Paul, S.M.; Skolnick, P. Buspirone attenuates learned helplessness behavior in rats. Drug Dev. Res. 1987, 10, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, L.M.; Nascimento, A.B.; Almeida, S.S. Differential response to gepirone but not to chlordiazepoxide in malnourished rats subjected to learned helplessness. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2008, 41, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, J.E.; Fleck-Kandath, C.; Mansbach, R.S. Effects of buspirone differ from those of gepirone and 8-OH-DPAT on unpunished responding of pigeons. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988, 30, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cott, J.M.; Kurtz, N.M.; Robinson, D.S.; Lancaster, S.P.; Copp, J.E. A 5-HT1A ligand with both antidepressant and anxiolytic properties. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 164–167. [Google Scholar]

- Rausch, J.L.; Ruegg, R.; Moeller, F.G. Gepirone as a 5-HT1A agonist in the treatment of major depression. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1990, 26, 169–171. [Google Scholar]

- Harto, N.E.; Branconnier, R.J.; Spera, K.F.; Dessain, E.C. Clinical profile of gepirone, a nonbenzodiazepine anxiolytic. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, C.S.; Ferguson, J.M.; Dale, J.L.; Heiser, J.F. A double-blind trial of low- and high-dose ranges of gepirone-ER compared with placebo in the treatment of depressed outpatients. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1996, 32, 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- Feiger, A.D. A double-blind comparison of gepirone extended release, imipramine, and placebo in the treatment of outpatient major depression. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1996, 32, 659–665. [Google Scholar]

- Alpert, J.E.; Franznick, D.A.; Hollander, S.B.; Fava, M. Gepirone extended-release treatment of anxious depression: Evidence from a retrospective subgroup analysis in patients with major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.B.; Ruwe, F.J.; Janssens, C.J.; Sitsen, J.M.; Jokinen, R.; Janczewski, J. Relapse prevention with gepirone ER in outpatients with major depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2005, 25, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielski, R.J.; Cunningham, L.; Horrigan, J.P.; Londborg, P.D.; Smith, W.T.; Weiss, K. Gepirone extended-release in the treatment of adult outpatients with major depressive disorder: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Clinical Review of Exxua (Gepirone) NDA. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2023/021164Orig1s000MedR.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Fabre, L.F.; Brown, C.S.; Smith, L.C.; Derogatis, L.R. Gepirone-ER treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) associated with depression in women. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eison, A.S.; Temple, D.L., Jr. Buspirone: Review of its pharmacology and current perspectives on its mechanism of action. Am. J. Med. 1986, 80, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissardo, J.P.; Caprara, A.L.F. Buspirone-associated Movement Disorder: A Literature Review. Prague Med. Rep. 2020, 121, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, Q.; Dou, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Fan, H.; Yang, X.; Ma, X. Side effects and cognitive benefits of buspirone: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hamik, A.; Oksenberg, D.; Fischette, C.; Peroutka, S.J. Analysis of tandospirone (SM-3997) interactions with neurotransmitter receptor binding sites. Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 28, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Egashira, N.; Harada, S.; Okuno, R.; Mishima, K.; Iwasaki, K.; Nishimura, R.; Fujiwara, M. Perospirone, a novel antipsychotic drug, inhibits marble-burying behavior via 5-HT1A receptor in mice: Implications for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 99, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y.; Yasui-Furukori, N.; Nakagami, T.; Saito, M.; Kaneko, S. Augmentation of antidepressants with perospirone for treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumi, I.; Masui, T.; Koyama, T. Long-term perospirone treatment with a single dose at bedtime in schizophrenia: Relevant to intermittent dopamine D2 receptor antagonism. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 520–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mahmood, I.; Sahajwalla, C. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of buspirone, an anxiolytic drug. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1999, 36, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasui-Furukori, N.; Furukori, H.; Nakagami, T.; Saito, M.; Inoue, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Tateishi, T. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of a new antipsychotic agent perospirone and its active metabolite, and its relationship with prolactin response. Ther. Drug Monit. 2004, 26, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balfour, J.A.; Fitton, A.; Barradell, L.B. Lornoxicam. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in the management of painful and inflammatory conditions. Drugs 1996, 51, 639–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Jia, M.; Jiang, X.; Wang, L. Pharmacokinetics and absorption mechanism of tandospirone citrate. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1283103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gepirone IR | Gepirone ER | |

|---|---|---|

| Dose | 10 mg | 20/25 mg daily |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 12.2 ± 6.3 | 3.6 ± 1.6–4.3 ± 2.8 |

| Tmax (h) | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 4.8 ± 1.9–5.6 ± 2.5 |

| AUC (30) (h × mg/mL) | 54.9 ± 25.6 | 51.8 ± 27.3–55.3 ± 28.2 |

| Plasma concentration profile | High peak-to-trough plasma concentration fluctuation | Steady state plasma concentration |

| Dosing interval | 12 h | 24 h |

| Study | Patient Population | Study Design | Dose(s) of Gepirone | Efficacy Outcomes | Safety Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilcox et al. 1996 [77] | N = 145 patients with MDD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Low-dose: 10–50 mg/day For 6 weeks. High-dose: 20–100 mg/day For 6 weeks. | Low-dose: No improvement in scales exception:

Improvements in scales:

| Adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and initially occurred after increasing the dose and subsided over time. |

| Feiger, 1996 [78] | N = 123 patients with MDD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Gepirone ER: 10–60 mg/day Imipramine: 50–300 mg/day For 8 weeks | Improvements in scales:

| Mild and transient side effects. |

| Feiger et al. 2003 [43] | N = 204 patients with moderate-to-severe MDD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 20 mg at day 1 40 mg at day 4 60 mg at day 7 80 mg at day 14 For 8 weeks | Efficacy across primary and secondary parameters:

| No serious adverse events occurred. |

| Alpert et al. 2004 [79] | N = 133 patients with anxious depression | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 20 mg at day 1 40 mg at day 4 60 mg at day 7 80 mg at day 14 For 8 weeks | Efficacy across primary and secondary parameters:

| Dizziness Nausea Headache |

| Keller et al. 2005 [80] | OL phase: N = 420 patients with MDD Double-blind continuation phase: N = 250 patients who met the criteria | Randomized, placebo-controlled, open-phase for 8-12 weeks, double-blind, placebo-controlled for additional 40-44 weeks | OL phase: 20 mg at day 1 40 mg at day 4 60 mg at day 6 80 mg at day 15 Double-blind continuation phase: Dosage that led to remission in OL phase. | OL phase:

| OL phase: Well tolerated, minimal Nausea Dizziness Headache Insomnia Vertigo Double-blind continuation phase: similar with placebo; Flu Syndrome Headache |

| Bielski et al. 2008 [81] | N = 248 patients with MDD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group | 20 mg at day 1 40 mg at day 4 40–60 mg at day 8 40–80 mg at day 15 | Efficacy across primary and secondary parameters:

| Dizziness Nausea Headache |

| CN105-083 [82] | N = 112 patients with moderate-to-severe depression | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Low dose:10–50 mg/day High-dose: 20–100 mg/day For 6 weeks and 20 weeks extension | Non-significant (p = 0.747) | - |

| CN105-078 [82] | N = 135 patients with moderate-to-severe depression | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Low dose: 10–50 mg/day High dose: 20–100 mg/day For 6 weeks and 20 weeks extension | Non-significant (p = 0.362) | - |

| FKG-GBE-008 [82] | N = 195 patients with moderate-to-severe depression | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 40–80 mg/day For 8 weeks | Non-significant (p = 0.195) | - |

| 134002 [82] | N = 211 patients with moderate-to-severe depression | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 20–80 mg/day For 8 weeks | Non-significant (p = 0.417) | - |

| 28709 [82] | N = 303 in Phase 1; N = 250 in Phase 2; patients with moderate-to-severe depression | Phase 1: Open-label phase 8–12 weeks; Phase 2: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 40–44 weeks | 20–80 mg | Non-significant (p = 0.10124) | - |

| Fabre et al. 2011 [83] | N = 921 female patients in 3 trials with MDD/atypical depressive disorder | Randomized, double-blind | Gepirone ER: 20 mg at day 1 40–60 mg at day 4 60–80 mg at day 14 Fluoxetine (134004, 134017): 20 mg/day start 40 mg/day at week 2 Paroxetine (134006): 20 mg/day start 30 mg/day at week 2 40 mg/day at week 3 | 134004:

at week 2 (p = 0.0001) at week 8/EOT (p = 0.007) | Dizziness Nausea No decreased libido compared to SSRIs |

| Fabre et al. 2012 [44] | N = 181 male patients with MDD | Randomized, double-blind | Gepirone ER: 40–80 mg/day Fluoxetine: 20–40 mg/day |

HAM-D17 non-responders (p = 0.011) week 4 MADRS non-responders (p = 0.002) week 4 HAM-D/MADRS responders non-significant | Dizziness Nausea |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gałka, N.; Tomaka, E.; Tomaszewska, J.; Pańczyszyn-Trzewik, P.; Sowa-Kućma, M. Gepirone for Major Depressive Disorder: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Evidence: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199805

Gałka N, Tomaka E, Tomaszewska J, Pańczyszyn-Trzewik P, Sowa-Kućma M. Gepirone for Major Depressive Disorder: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Evidence: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(19):9805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199805

Chicago/Turabian StyleGałka, Natalia, Emilia Tomaka, Julia Tomaszewska, Patrycja Pańczyszyn-Trzewik, and Magdalena Sowa-Kućma. 2025. "Gepirone for Major Depressive Disorder: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Evidence: A Narrative Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 19: 9805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199805

APA StyleGałka, N., Tomaka, E., Tomaszewska, J., Pańczyszyn-Trzewik, P., & Sowa-Kućma, M. (2025). Gepirone for Major Depressive Disorder: From Pharmacokinetics to Clinical Evidence: A Narrative Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(19), 9805. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199805