Assessing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Management

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Study Outcomes

2.7. Quality Assessment

3. Results

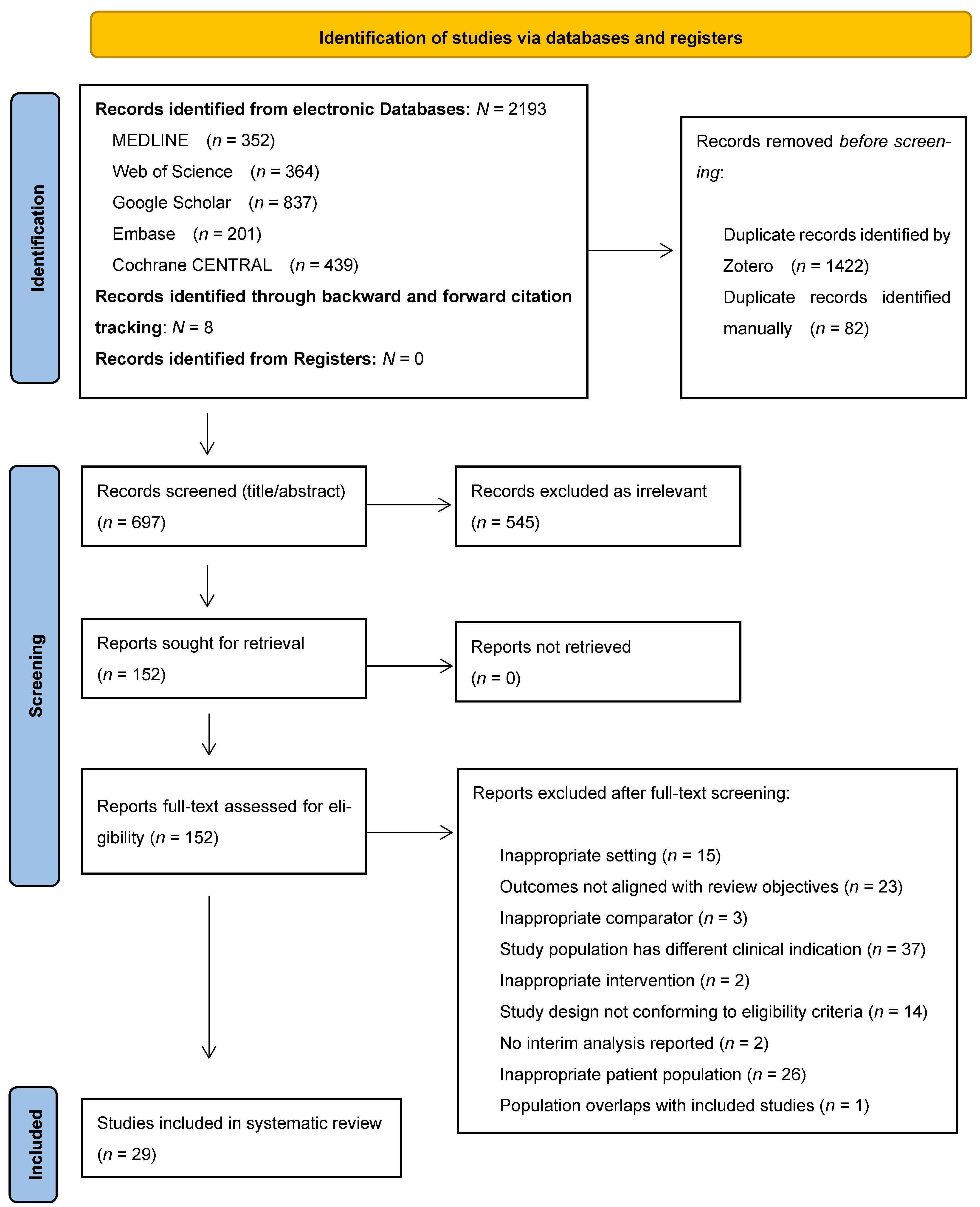

3.1. Search Results and Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Mortality Outcomes Following Monoclonal Antibody Intervention

3.2.1. Anti–TNF-α Monoclonal Antibodies

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Investigational Drug | Sample Size, Demographics | Study Arms, Follow-Up | Stratification Subgroup Analysis | Sepsis Criteria | Outcomes | Drug Administration | Results | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham et al., 1995, (USA, Canada) [57] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | Anti-TNF-α mAb (murine IgG1) | N = 994 enrolled; 971 infused. Mean age ~59 yrs. Male: ~56%. Balanced arms. Similar APACHE II (~25). | 3 arms: TNF-α mAb in two different doses vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified: Shock vs. non-shock pre-randomization. Subgroups: Shock status, APACHE II, infection type (GPB/GNB). | Based on Bone et al. Study (1989) [49]: Suspected infection and SIRS and organ dysfunction. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: Mortality at days 3, 7, and 14, AEs, HAMA titers, labs, vitals, APACHE II changes. | Single IV infusion (7.5 or 15 mg/kg TNF-α mAb) within 4 h post-randomization. | 28-day all-cause mortality: TNF-α mAb 15 mg/kg 31.3%, 7.5 mg/kg 29.5%, placebo 33.1% (NS). In shock subgroup: Trend to reduced mortality (15 mg/kg 37.7%, 7.5 mg/kg 37.8%, placebo 45.6%, p = 0.15–0.20). Early mortality at day 3: Significant reduction in TNF-α mAb. Late organ failure reversal: NS. Safety: AEs similar across groups (~4.6%). | Low |

| Abraham et al., 1998, (USA, Canada) [58] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | Anti-TNF-α mAb (murine IgG1) | N = 1879 septic shock patients: 948 TNF-α mAb, 925 placebo. Mean age: ~59 yrs. Male: 60.5%. White: ~65%. Mean APACHE II: 28.4 (TNF-α mAb) vs. 28.8 (placebo). | 2 arms: TNF-α mAb vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by center. Subgroups: Baseline IL-6 (>1000 pg/mL), detectable TNF-α, shock duration, infection type (GPB/GNB). | Septic shock ≤ 12 h onset; SIRS + organ dysfunction (hypotension refractory to fluids, altered mental status, hypoxemia, metabolic acidosis, oliguria, DIC) per Bone 1989 [49] adaptations. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: 7- and 14-day mortality, shock reversal, prevention of new shock/organ failure, coagulopathy rates, AEs, anti-TNF-α mAb antibodies, tolerability. | Single IV infusion (TNF-α mAb 7.5 mg/kg or placebo—0.25% human serum albumin) over ~30 min, within 4 h of randomization. | 28-day mortality: 40.3% (TNF-α mAb) vs. 42.8% (placebo) (p = 0.27). Shock reversal/duration or prevention: NS difference. Coagulopathy ↓ with TNF-α mAb at day 7 (p < 0.001), day 28 (p = 0.005). Cytokines: No survival benefit baseline IL-6 or TNF-α. Safety: AEs similar, well tolerated; no anti-TNF-α mAb antibodies detected. | Low |

| Aikawa et al., 2013, (Japan) [71] | RCT, multicenter, phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled | AZD9773 Ovine polyclonal Fab frags of IgG (anti-TNF-α) | N = 20 sepsis patients: AZD9773 cohort 1 (n = 7), cohort 2 (n = 7), placebo (n = 6). Mean age: 75 yrs; Male: ~45%. APACHE II mean ~26; SOFA mean ~10. | 3 arms: Low-dose and high-dose AZD9773 vs. placebo. Follow-up: To day 29. | NR. | Infection + ≥2 SIRS criteria (incl. temp or WBC) + cardiovascular and/or respiratory failure per Bone 1992 [50]. | Primary: Safety/tolerability PK/PD. Secondary: Exploratory outcomes (SOFA, VFDs, ICU-free days, infection rates, mortality at day 29). | IV infusion: Cohort 1: 250 U/kg loading, then 50 U/kg q12h × 9 doses. Cohort 2: 500 U/kg loading, then 100 U/kg q12h × 9 doses or placebo. | 29-day all-cause mortality: AZD9773 cohort 1 (low dose): 14.3% (1/7), AZD9773 cohort 2 (high dose): 28.6% (2/7), placebo: 33.3% (2/6). SOFA and organ failure resolution: Similar. Cytokines: TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8 ↓ more in AZD9773 arms. Safety: No treatment discontinuations due to AEs. | Low |

| Albertson et al., 2003, (USA) [59] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | MAB-T88 Human IgM mAb | N = 826 enrolled (411 MAB-T88, 415 placebo). Mean age: ~57 yrs. Male: ~60%. APACHE II mean: ~26.8. | 2 arms: MAB-T88 vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by shock presence, age, APACHE II, isolated UTI. Subgroups: documented ECA infection, bacteremia. | Temperature: ≥35.5 °C or ≥38.3 °C, tachycardia: ≥90 bpm (no β-blockers), tachypnea: ≥20 breaths/min or mech. vent., hypotension, or dysfunction of ≥2 end-organs, presumptive G- infection (culture/stain). | Primary: 28-day survival. Secondary: AEs, organ dysfunction, lab parameters. | Single IV infusion over 30 min: 300 mg MAB-T88 or placebo (albumin). | 28-day all-cause mortality: MAB-T88 (34.2%) vs. placebo (30.8%) in ECA group, p = 0.44. All 826 patients: MAB-T88 (37.0%) vs. placebo (34.0%), p = 0.36. Safety: More AEs in MAB-T88 group (p < 0.05). | Low |

| Angus et al., 2000, (USA) [60] | RCT, multicenter, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | E5 Murine mAb IgM | N = 1102 randomized; 1090 treated (550 E5, 552 placebo). Mean age: 60 yrs, Male: 55%. Hypotension: ~75%. Organ dysfunction in 84%. Shock at presentation: 46%. | 2 arms: E5 vs. placebo Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by shock presence. Subgroups pre-specified by shock status, comorbidities, organ failure, infection site, organism. | Severe sepsis per ACCP/SCCM 1992 [50]: SIRS + hypotension or hypoperfusion + organ dysfunction; Gram-negative infection documented or probable. | Primary: 14-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: 28-day mortality, subgroup mortality (shock status), organ dysfunction resolution, lab abnormalities, AEs, and withdrawal due to AEs. | IV infusion: E5 2 mg/kg IV infusion over 1 h × 2 doses (24 h apart) vs. placebo. | 14-day mortality: E5 29.7% vs. placebo 31.1% (p = 0.67). 28-day mortality: E5 38.5% vs. placebo 40.3% (p = 0.56). NS difference in any subgroup analysis. AEs: Similar frequency and profile. | Low |

| Bauer et al., 2021 (Germany) [77] | RCT, multicenter, phase IIa, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | Vilobelimab (IFX-1) recombinant mAb anti-C5a | N = 72 patients with severe sepsis/septic shock. Mean age: 63 yrs (vilobelimab) vs. 64 yrs (placebo). Male: 61% (vilobelimab) vs. 67% (placebo). Baseline APACHE II median: ~17.5–22.5. SOFA median: ~8.5–9.0 | 4 arms: Vilobelimab, three cohorts, vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by infection focus (abdominal or pulmonary). Subgroups post hoc combining cohorts 2 + 3. | Sepsis-3 definition [12]. Infection-related organ dysfunction onset < 6 h or vasopressor therapy < 3 h. | Co-primary: PD (C5a levels), PK (vilobelimab levels), safety/tolerability. Secondary: 28d all-cause mortality (ACM), SOFA, ICU-/ventilator-/vasopressor-/RRT-free days, cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, IL-10), antibiotic days. | IV infusion: Vilobelimab cohort 1: 2 × 2 mg/kg IV (0, 12 h); cohort 2: 2 × 4 mg/kg IV (0, 24 h); cohort 3: 3 × 4 mg/kg IV (0, 24, 72 h); placebo matching volumes/times. | 28-day all-cause mortality: Placebo 12.5%, cohort 1 37.5%, cohort 2 18.8%, cohort 3 12.5%. Critical care: Cohorts 2 + 3 had more ICU- and ventilator-free days. Cytokines: Vilobelimab led to dose-dependent ↓C5a; no impact on MAC formation. SOFA scores: No difference in SOFA, vasopressor-, RRT-free days. Safety: AEs frequent but similar across groups. | Low |

| Bernard et al., 2014, (France, Belgium, Canada, Australia, Czech Republic, Finland, Spain) [72] | RCT, multicenter, phase IIb, double-blind, placebo-controlled | AZD9773 Ovine polyclonal Fab frags of IgG (anti-TNF-α) | N = 300 patients with severe sepsis/septic shock. N = 296 treated (100/arm: low-/high-dose AZD9773, placebo). Median age: 62. Male: 66%. APACHE II: mean 25.2; baseline SOFA: mean 9.0. | 3 arms: Low-dose AZD9773 and high-dose AZD9773 vs. placebo Follow-up: To day 90. | Stratified by APACHE II, age, region, mech. ventilation. Subgroups: baseline TNF-α quartiles, infection site, organ failures, gender, age. | Severe sepsis/septic shock: Infection + ≥2 SIRS criteria (incl. temp/WBC) + cardiovascular and/or respiratory failure (Bone 1989 criteria) [49]. | Primary: Mean VFDs to day 29. Secondary: 7-, 29-, and 90-day mortality, time to death, shock-free days, organ-failure-free, ICU-free days (D15), SOFA score, infection relapse, PD, AEs. | IV infusion; loading dose + maintenance q12h for 5 days (max 10 doses); dose capped at 100 kg body weight. | 29 d mortality: Placebo 20%, low-dose 15%, high-dose 27% (NS). VFDs: Low-dose 19.7, high-dose 17.3, placebo 18.3 (NS). SOFA score: Similar improvement across groups. Infection relapse and ICU/organ-failure-free days: NS. Safety: TNF-α significantly reduced (p < 0.001); no effect on IL-6/IL-8; AEs similar across groups; no safety signals; no subgroup showed clear benefit. | Low |

| Bone et al., 1995, (USA) [61] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | E5 Murine mAb IgM | N = 847 randomized, N = 830 treated, N = 811 analyzed. Balanced gender distribution and similar APACHE II scores. | 2 arms: E5 vs. placebo. Follow-up: 30 days. | Stratified by documented GN sepsis, organ failure presence, bacteremia status. Subgroups: On organ failure resolution, mortality in subsets. | Known/suspected G- infection: Clinical sepsis (≥2 SIRS criteria). Organ dysfunction (renal, respiratory, coagulation, CNS, hepatic). Exclusion: Refractory shock. | Primary: 30-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: Resolution/prevention of organ failures, AEs, (HAMA) development, length of hospitalization. | IV infusion, E5 2 mg/kg per dose, 2 doses ~24 h apart, 1 h infusion each or placebo. | 30-day mortality: 30% E5 vs. 33% placebo, (p = 0.21). Organ failure resolution: Improved with E5 (48% vs. 25%, p = 0.005). All patients with organ failure: 41% (E5) vs. 27% (placebo) (p = 0.024). Prevention of new organ failures: ARDS 5% (E5) vs. 12% (placebo) (p = 0.007). CNS Dysfunction 4% (E5) vs. 10% (placebo) (p = 0.05). Safety: Hypersensitivity reactions: 2.6% (E5), HAMA development: 44% (E5) vs. 12% (placebo). | Low |

| Cohen et al., 1996, (14 countries) [73] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | BAY 1351 Murine anti-TNF-α mAb | N = 564 enrolled, 553 infused. 420 in shock for primary analysis. Male: ~60%. APACHE II ~22 (mean). | 3 arms: BAY 1351 vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratification by shock vs. non-shock. Subgroups by infection type, APACHE II score. | SIRS + organ hypoperfusion/dysfunction per Bone 1989 [49] criteria (infection, temp, HR, RR, organ failure). | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality rate. Secondary: Shock reversal and frequency of organ failures, AEs. | IV infusion over 30 min; single dose of BAY 1351 15 or 3 mg/kg within 16 h of sepsis onset or placebo (human albumin). | 28 d mortality: 3 mg/kg 31.5% vs. placebo 39.5% (NS); 15 mg/kg 42.4% (NS). Shock subgroup: 3 mg/kg 36.7% vs. placebo 42.9% (NS). Organ failure resolution: Improved shock reversal, delayed organ failure in treatment groups (p = 0.007, p = 0.01), organ failure rates: 15-mg/kg 40.2%, 3-mg/kg 44.3%, placebo 59.2% (p = 0.03, p = 0.06). Safety: AEs similar; high anti-mouse antibody development. | Low |

| Darenberg et al., 2003, (Sweden, Norway, Finland, Netherland) [80] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | IVIG | N = 21 patients (10 IVIG, 11 placebo). Mean age: ~52 yrs. Male: 45%. Baseline SOFA: ~11; SAPS II: ~52–53. | 2 arms: IVIG vs. placebo. Follow-up: 180 days. | NR | STSS defined by hypotension + multiorgan failure per Working Group on Severe Streptococcal Infections consensus. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: SOFA score changes, shock resolution time, tissue infection progression, 180-day survival, neutralizing Ab activity safety, AEs. | IV infusion: 1 g/kg IVIG day 1, then 0.5 g/kg days 2 and 3 or placebo 8 (1% albumin diluted in saline). | 28 d mortality: 10% (IVIG) vs. 36% (placebo) (p = 0.21)/ 180 d mortality: 20% (IVIG) vs. 36% (placebo). SOFA: Improved significantly on days 2 and 3 (p = 0.02, 0.04). Shock resolution: Median 96 h (IVIG) vs. 108 h (placebo). Safety: No difference in cytokines; no drug-related AEs, plasma neutralizing activity ↑ with IVIG. | Low |

| DeSimone et al., 1988 (Italy) [81] | RCT, open-label prospective | IVIG, monomeric, poly-specific human IgG | N = 24 sepsis patients in ICU with severe infections (12M/12F), randomized: IVIG + antibiotics (n = 12) vs. antibiotics-only (n = 12). Mean age: 44 yrs (24–71). | 2 arms: IVIG + AB vs. AB alone; IVIG dose 0.4 g/kg day 1, 0.2 g/kg day 3, optional 0.4 g/kg day 8. Follow-up: Until ICU discharge or death. | NR | Clinical + lab evidence of severe sepsis in ICU patients (e.g., septicemia, pneumonia, meningitis, peritonitis, ARDS). | Efficacy measures: Survival probability (Cox–Mantel method), median survival time, culture negativization rate, duration of antibiotic therapy, changes in serum IgG concentration, AEs to IVIG. | IV infusion IVIG 6% saline; doses as above; AB per standard or sensitivity tests. | Mortality: 58% (7/12) in IVIG + antibiotics vs. 75% (9/12) in antibiotics alone (p < 0.1). Median survival: 30 days (IVIG) vs. 10 days (antibiotics alone). Defervescence: IVIG group had significantly shorter time (10 vs. 16 days; p < 0.01). Culture negativization: 40% in IVIG vs. 8% in AB alone (p < 0.01). ICU days on antibiotics: IVIG group 38% vs. 95% in AB alone (p < 0.01). Adverse Events: No adverse reactions or toxicity related to IVIG. | High |

| Dhainaut et al., 1995, (France, Belgium) [74] | RCT, multicenter phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | CDP571 Humanized anti-TNF-α mAb | N = 42 patients with rapidly progressing septic shock on mech. vent. Mean APACHE II score: 22 (placebo) vs. 23 (CDP571). | 5 arms: CDP571 vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Subgroups by dose and baseline severity. | Septic shock within 12 h: Infection + fever/hypothermia + tachycardia + tachypnea/ventilation + vasopressor-dependent hypotension + organ hypoperfusion (lactate ↑, PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 280, oliguria, mental status change). | Primary: Safety, PK, immune response. Secondary: Cytokine levels, 28 d all-cause mortality. | IV infusion over 5 min, single dose, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, or 3.0 mg/kg CDP571 or placebo within 12 h of septic shock diagnosis. | 28 d overall mortality: 62%; no difference placebo vs. CDP571 except 0.3 mg/kg group (all died early, worse baseline). Safety: CDP571 well tolerated, no drug-related AEs. Efficacy: Dose-dependent TNF-α ↓; IL-1β and IL-6 ↓ faster with CDP571; low immunogenicity; PK half-life 105–154 h. | Low |

| Gallagher et al., 2001, (USA) [62] | RCT, multicenter phase II, open-label, placebo-controlled, prospective | Afelimomab Murine anti-TNF-α mAb fragment | N = 48 patients (12 single-dose, 36 multiple-dose). 30 severe sepsis patients randomized into 3 dose groups. Mean age: ~60 yrs. M/F: ~50%. Baseline APACHE II mean ~26. | 4 arms: Afelimomab vs. placebo; single dose (n = 12) or multiple doses q8h × 9 doses (n = 36). Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by baseline IL-6 (<1000 vs. ≥1000 pg/mL). Subgroups: Suggested survival benefit in high IL-6 group. | Clinical sepsis syndrome per Bone 1989 [49]: SIRS (fever/hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnea) + hypotension or organ dysfunction (shock, metabolic acidosis, hypoxia, renal failure, coagulopathy, mental status change). | Primary: PKs. Secondary: Safety, immunogenicity, serum TNF-α and IL-6 concentrations, 28 d all-cause mortality, serum afelimomab concentrations, AEs. | IV administration over 20 min: Doses of 0.3, 1.0, or 3.0 mg/kg; single dose or multiple doses every 8 h × 9 doses (72 h total). | 28 d mortality: Placebo 56%, afelimomab 0.3 mg/kg 33%, 1.0 mg/kg 22%, 3.0 mg/kg 22%. Mortality association with baseline IL-6 (p = 0.001). Safety: Afelimomab was well-tolerated. Efficacy: ↑TNF-α (antibody-bound), ↓IL-6 in treatment groups. AEs: 41% developed HAMA (no clinical sequelae). | High |

| Greenman et al., 1991, (USA) [63] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | E5 Murine mAb IgM | N enrolled = 486; analyzed = 468 (efficacy), 479 (safety). Mean age: ~60–64 yrs. Male: ~66%. APACHE II mean: 17. | 2 arms: E5 vs. placebo. Follow-up: 30-days. | Stratified by shock status (shock vs. non-shock). Subgroups by bacteremia status. | Suspected/confirmed GNB + systemic septic response: temp > 38 °C or <35 °C, WBC > 12 × 109/L or <3 × 109/L, immature forms ≥ 20%, Gram-negative culture ± organ dysfunction (ARDS, ARF, DIC, shock). Septic response (≥1): SBP < 90 or ↓30 mmHg; BD > 5; SVR < 800; RR > 20 or mech. vent. > 10 L/min; organ dysfunction. | Primary: 30-day mortality. Secondary: Resolution of organ failures (ARDS, ARF, DIC), AEs. | E5 2 mg/kg IV over 1 h; 2nd dose at 24 ± 4 h. Comparator: Placebo IV, same schedule. | Overall 30 d mortality: E5 38% vs. placebo 41% (NS). Non-shock subgroup: E5 improved survival (RR 2.3, p = 0.01). Shock subgroup: No difference. Organ failure resolution: E5: 54% vs. placebo: 30% (p = 0.05). Safety: AEs similar except 1.6% reversible allergic reactions in E5 group. | Low |

| Hotchkiss et al., 2019, (USA) [64] | RCT, multicenter phase Ib, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | BMS-936559 Anti–PD-L1, fully human IgG4 mAb | N enrolled = 35; randomized = 25; treated = 24 with sepsis, Median age: 62 yrs (range 24–76). Male: 45%. Baseline SOFA ~7.6 (±3.6). | 6 arms: BMS-936559: 10 mg, 30 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg, and 900 mg (10–900 mg; n = 20) vs. placebo (n = 4). Follow-up: 90 days. | NR | Documented/suspected infection + sepsis onset ≥ 24 h + organ dysfunction (hypotension, ARF, AKI) + ICU care + sepsis-associated immunosuppression: ALC ≤ 1100 cells/μL within 96 h of treatment. | Primary: Safety/tolerability (90 d), AEs. Secondary: PK, receptor occupancy, immune biomarkers. | Single-dose BMS-936559 (10–900 mg) or placebo, IV infusion on day 1. | Overall mortality: 25%. Doses (n = 4 per group): 10 mg: 2/4, 30 mg: 2/4, 100 mg: 1/4, 300 mg: 1/4, 900 mg: 0/4, placebo: 0/4. Safety: AEs mostly mild/moderate, no cytokine storm, increased mHLA-DR at higher doses, NS cytokine changes, safety profile acceptable. | Low |

| Konrad et al., 1996, (Germany, UK, Spain, Austria, France, Switzerland) [75] | RCT, multicenter, phase II, open-label, placebo-controlled, prospective | MAK 195F Murine IgG3 F(ab’)2 fragment mAb | N = 122, severe sepsis or septic shock Mean age: 56 yrs. ~59% developed sepsis in ICU. Sex distribution balanced. Mean APACHE II score 21.7. | 4 arms: MAK 3 diff. dose groups vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days or until death. | Stratification: Retrospective by baseline IL-6 (>1000 pg/mL vs. <1000 pg/mL); no benefit by shock, organ dysfunction, APACHE II, or TNF levels. | Sepsis per Bone 1989 [49] criteria + 5 additional criteria within 24 h: clinical sepsis evidence, temp ≥ 38 °C or ≤35.6 °C, HR ≥ 90 bpm (no beta-blocker), RR ≥ 20 or mechanical ventilation, hypotension, or systemic toxicity/end-organ perfusion abnormalities. | Primary: Safety, 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: Changes in serum TNF and IL-6 levels, efficacy in subgroups (especially by IL-6), AEs, HAMA, organ dysfunction scores, laboratory abnormalities, tolerability of repeated dosing. | MAK 195F 0.1 mg/kg, 0.3 mg/kg, or 1.0 mg/kg or placebo IV, 9 doses at 8 h intervals over 3 days, each dose infused over 15 min. | 28 d mortality: Overall (placebo 41%, MAK 195F 0.1 mg/kg 56%, 0.3 mg/kg 47%, 1.0 mg/kg 38%, p = 0.45). Subgroup (IL-6 > 1000 pg/mL): Trend for ↓ mortality in high-dose MAK 195F (1 mg/kg) (p = 0.076). Cytokines: ↓IL-6 in all MAK 195F groups within 24 h vs. no decrease in placebo. Safety: MAK 195F well-tolerated. AEs similar across groups. | High |

| Laterre et al., 2021, (Belgium, France, Germany, The Netherlands) [79] | RCT, multicenter phase IIa, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Adrecizumab Humanized, mAb targeting ADM | N = 301 septic shock patients. Median age 67 yrs (adrecizumab) vs. 68 yrs (placebo). 70.5% male (adrecizumab) vs. 70.4% male (placebo). Baseline severity: SOFA median 9–11, APACHE II median 32–33. | 3 arms: Adrecizumab vs. placebo (n = 152). Follow-up: 90 days. | Stratified by bio-ADM > 70 pg/mL. Subgroups included baseline bio-ADM, SOFA, APACHE II. | Septic shock based on Sepsis-3 [12] criteria. | Primary: 90-day mortality, TEAEs, tolerability (infusion interruptions, hemodynamics). Secondary: SSI, ΔSOFA, 28 d mortality, ICU/hospital length of stay, PK/PD. | Single IV infusion of adrecizumab (2 or 4 mg/kg) or placebo administered over ~1 h. | 90 d mortality: 23.9% (adrecizumab) vs. 27.7% (placebo) (HR 0.84, p = 0.44). Safety: TEAEs similar across groups. SSI (MD 0.72, 95% CI −1.93–0.49, p = 0.24). ΔSOFA score in adrecizumab group (MD 0.76, 95% CI 0.18–1.35, p = 0.007). NS difference in ICU/hospital length of stay. | Low |

| McCloskey et al., 1994, (USA) [65] | RCT, multicenter phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | HA-1A Human mAb (anti-endotoxin) | N = 2199 patients enrolled, N = 621 analyzed of primary group with confirmed GNB. | 2 arms: HA-1A vs. placebo. Follow-up: 14 days post-infusion. | Subgroups: With vs. without GNB. | Patients in shock (systolic BP < 90 mmHg after fluid challenge or vasopressors) within 6 h of enrollment, shock onset within 24 h, presumptive GN infection. | Primary: 14-day all-cause mortality in patients with GNB. Secondary: Safety of HA-1A in patients without GNB, AEs. | IV administration: 100 mg of HA-1A or placebo. | 14-day mortality: 33% (HA-1A) vs. 32% (placebo) in GNB (p = 0.864), 41% (HA-1A) vs. 37% (placebo) without GNB (p = 0.073). Safety: AEs similar between groups. | Some concerns |

| Morris et al., 2012, (USA) [66] | RCT, multicenter, phase IIa, double-blind, placebo-controlled | AZD9773 Ovine polyclonal Fab frags of IgG (anti-TNF-α) | N = 70 patients treated (47 AZD9773, 23 placebo). Mean APACHE II score: 25.9. Mean age: ~56 yrs. 46% male/54% female. | 6 arms: AZD9773 cohorts 1–5 (various doses) vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Subgroups by dose cohorts. | Severe sepsis with infection, SIRS, cardiovascular/respiratory organ dysfunction; treatment within 36 h of organ failure. | Primary: Safety/tolerability. Secondary: PK, PD, organ failure-free days, ventilator-free days, 28-day mortality, TNF-α and IL-6 serum levels, SOFA scores, AEs, ECG measurements, HASA assessment. | IV administration: Single doses: 50 or 250 units/kg. Multiple doses: Loading + maintenance (every 12 h for 5 days). | 28-day mortality: AZD9773 27.7% vs. placebo 26.1% (NS). SOFA-score changes: Improved similarly. Safety: No dose-limiting toxicities. NS differences in SAEs, immunogenicity low (12.8%). | Low |

| Panacek et al., 2004, (USA, Canada) [67] | RCT, multicenter, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | Afelimomab Murine anti-TNF-α mAb fragment | N = 2634 IL-6 positive subgroup, N = 998 (488 afelimomab, 510 placebo). Mean age: ~59 yrs; Male: ~60%. ~75% in shock; ~40% post-surgical, ~60% medical; baseline severity scores (APACHE II, SAPS II, MOD, SOFA) generally balanced; ~40% bacteremic. | 2 arms: Afelimomab vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratification by IL-6 level (rapid qualitative test, threshold ~1000 pg/mL) and study center. | Per ACCP/SCCM [50] consensus criteria for septic shock within 24 h. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality (IL-6 positive group). Secondary: Organ dysfunction (MOD, SOFA scores), serum cytokine levels (IL-6, TNF), AEs. | 1 mg/kg afelimomab IV over 15 min every 8 h for 3 days (total 9 doses). | 28-day mortality: IL-6 positive: 43.6% (afelimomab) vs. 47.6% (placebo), 5.8% risk reduction (p = 0.041). IL-6 negative: 25.5% vs. 28.6%. All patients: 32.2% vs. 35.9%. Organ dysfunction: Faster improvement and greater TNF/IL-6 reduction with afelimomab. Safety: Similar AE rates, HAMA formation 23.6% vs. 6.3% placebo (no clinical impact), no increase in secondary infections. | Low |

| Reinhart et al., 2001, (Germany, Sweden, The Netherlands, UK and Northern Ireland, Belgium, Spain, Israel) [76] | RCT, multicenter, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group | Afelimomab Murine anti-TNF-α mAb fragment | N = 446 analyzed septic patients (224 afelimomab, 222 placebo). Mean age: 58 years. Male: 62%. Baseline severity: APACHE II ~23, APACHE III ~98, SAPS II ~54. | 2 arms: Afelimomab vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by IL-6 rapid immunostrip test (>1000 pg/mL positive vs. negative). Subgroups: IL-6-positive randomized. | Presumed infection + ≥5 criteria within 24 h: infection evidence, temp ≥ 38 °C or ≤35.6 °C, tachycardia or tachypnea or MV, hypotension or vasopressors, organ dysfunction/perfusion abnormalities (e.g., altered mental status, hypoxemia, lactate ↑, oliguria, DIC, coagulation abnormalities, low CI with low SVR). | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: Organ failure reversal (MODS, SOFA), hospital discharge status, AEs, vital signs, laboratory parameters, HAMA development. | Afelimomab 1 mg/kg IV every 8 h × 9 doses over 3 days (15 min infusions). | Mortality: Afelimomab 54.0% vs. placebo 57.7% (NS, p = 0.36). SOFA/MODS Δ and labs: MODS showed earlier resolution trend (NS); IL-6 levels significantly reduced at 8 h and 72 h with afelimomab. Safety: Similar AE profiles, immunogenicity (16% anti-mouse IgG) without clinical allergy, IL-6 test predicted higher mortality in positive vs. negative (55.8% vs. 39.6%, p < 0.001). | Low |

| Reinhart et al., 2004, (Germany, The Netherlands) [78] | RCT, multicenter phase I, double-blind, placebo-controlled | IC14, recombinant chimeric anti-CD14 mAb | N = 40 with severe sepsis. Mean age: ~59 yrs. M/F: 30/10. Baseline APACHE II: 15.5–22.4. MOD score: 4.4–6.4. | 5 arms: Four cohorts (dose-ranging) vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | NR. | Severe sepsis: ≥2 SIRS criteria + sustained hypotension or organ hypoperfusion (Bone 1992 criteria [50]). | Primary: Safety, PK/PD. Secondary: 28-day all-cause mortality, MOD score, cytokine levels, AEs. | IV infusion over 60 min: IC14 1 mg/kg single dose; IC14 4 mg/kg single dose; IC14 4 mg/kg daily ×4 days; IC14 4 mg/kg day 1 + 2 mg/kg days 2–4; or placebo. | 28-day mortality: NS difference, overall 20%. IC14 (4 mg/kg) single-dose 37.5%, multiple-dose 25%. MOD score change: NS change. Safety: NS differences in event incidence or lab changes between groups, well tolerated. | Low |

| Rice et al., 2006, (USA, Canada) [68] | RCT, multicenter phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled | CytoFab Affinity-purified, polyclonal ovine anti-TNF-α IgG Fab fragments | N = 81 severe sepsis patients (43 CytoFab, 38 placebo). Mean age: 56.1 (CytoFab) vs. 56.3 (placebo) years. Male: 60% (CytoFab) and 55% (placebo). Mean APACHE II 24.2 (CytoFab) vs. 24.4 (placebo). Baseline organ dysfunction: All had shock or ≥2 organ dysfunctions. | 2 arms: CytoFab vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Subgroups: Post hoc analysis by baseline plasma TNF-α concentrations (detectable vs. undetectable). | ICU patients with documented/presumed infection + ≥3 modified SIRS criteria + shock or ≥2 organ dysfunctions (Bone 1992 [50]). Organ dysfunction: As per Brussels score (renal, hepatic, coagulation, pulmonary, cardiovascular). | Primary: Shock-free days (14 d), ventilator-free days (28 d). Secondary: 28-day all-cause mortality, ICU-free days, cytokine (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8) levels, organ dysfunction resolution. Safety: AEs, HASA, drug tolerability. | CytoFab: 250 units/kg IV loading dose, then 9 maintenance doses of 50 units/kg IV every 12 h (max dosing weight 100 kg) vs. placebo: 5 mg/kg human albumin IV, same schedule (total 10 doses over 5 days). | Shock-free days: CytoFab 10.7 vs. placebo 9.4; p = 0.27. Ventilator-free days: CytoFab 15.6 vs. placebo 9.8 (p = 0.021). ICU-free days: CytoFab 12.6 vs. placebo 7.6 (p = 0.030). 28-day mortality: 26% (CytoFab) vs. 37% (placebo), (p = 0.274). Safety: Plasma TNF-α and IL-6 reduced with CytoFab, AEs similar; HASA detected in 41% CytoFab patients without clinical effects. | Some concerns |

| Rodríguez et al., 2005, (Spain, Argentine) [82] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective | Pentaglobin IVIG IgM-enriched polyclonal IgG/IgM/IgA | N = 56 patients randomized: 29 IVIG group, 27 control group (albumin). Mean 57.8 (IVIG) vs. 60.2 (control) years, 51.7% male (IVIG), 55.6% male (control). APACHE II score: 18.2 ± 6.1 (IVIG), 19.0 ± 7.2 (control). | 2 arms: Pentaglobin vs. placebo (albumin). Follow-up: Until ICU discharge or death. | Stratified by center. Subgroups: Shock vs. severe sepsis, appropriate vs. inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy. | Severe sepsis or septic shock (1992 ACCP/SCCM [50] criteria) of intra-abdominal origin. SIRS + surgically confirmed abdominal infection. Organ dysfunction/failure per detailed criteria. | Primary: ICU mortality. Secondary: Organ dysfunction/failure scores, reoperation rates, impact of IAT, AEs. | IV infusion: IVIG (Pentaglobin) 7 mL/kg/day IV × 5 days vs. 5% human albumin (control). | Mortality: IVIG 27.5% vs. control 48.1%, NS (p = 0.06), with appropriate ATB: IVIG 8.7% vs. control 33.3% (p < 0.04), IAT linked to 87.5% mortality (OR 19.4, p < 0.05). Organ failure/dysfunction scores: NS. Reoperation rate: IVIG 17.2% vs. control 29.6%. Safety: NS increase in AEs in IVIG group. | Some concerns |

| Toth et al., 2013, (Hungary) [83] | RCT, prospective placebo-controlled, pilot study | Pentaglobin IVIG IgM-enriched polyclonal IgG/IgM/IgA | N = 33 (16 IgM, 17 placebo) patients with early septic shock and severe respiratory failure. Median age: ~56–60 yrs. Sex: ~48% male/52% female. Baseline SAPS II ~25–26. | 2 arms: Pentaglobin vs placebo. Follow-up: 8 days. | NR. | Per ACCP/SCCM [50] consensus criteria for septic shock. | Primary: MODS score changes. Secondary: 28 d all-cause mortality, CRP, PCT, ICU length of stay, ventilation days. | Pentaglobin 5 mL/kg IV infusion over 8 h × 3 days vs. placebo (0.9% NaCl). | Mortality: IgM 4/16 survived vs. placebo 5/17 (NS). Organ failure scores changes and lab parameters: MODS unchanged, CRP levels significantly lower in IgM group on days 4–6, PCT no diff. | High |

| Weems et al., 2006, (USA) [69] | RCT, multicenter phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled | Tefibazumab Humanized IgG1 anti-ClfA mAb | N = 60 patients with documented SAB. 70% healthcare-associated infections; 57% with SAB-related complications at baseline. Mean age: ~54 yrs. Male: ~58%. APACHE II mean 8.6. | 2 arms: Tefibazumab + AB vs. placebo + AB. Follow-up: 8 weeks. | Stratified by SAB association (healthcare-associated vs. non-healthcare-associated). Subgroups by MRSA/MSSA. | Positive blood culture for S. aureus obtained ≤ 72 h prior to infusion. Patients with septic shock were excluded. AB use not standardized. | Primary: PK of tefibazumab AEs, lab alterations, immunogenicity (anti-tefibazumab antibodies). Secondary: Activity assessed by CCE, SAB-related complication, microbiological relapse, or death. | Single IV infusion: Tefibazumab 20 mg/kg single infusion + AB vs. Placebo (0.9% saline) + AB over 30 min. | CCE: Tefibazumab 6.7% vs. placebo 13.3% (NS), deaths: 1 vs. 4, no sepsis progression in tefibazumab group vs. 4 in placebo, PK half-life ~18 days, NS differences in hospital/ICU days or ventilation Safety: AEs similar | Some concerns |

| Werdan et al., 2007, (Germany) [84] | RCT, multicenter phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled | IVIG | N = 653 enrolled; 624 per protocol. Mean age: ~57 years. Male: 74.5% (ivIgG), 66.7% (placebo). Baseline APACHE II: ~27.6–28.0. Sepsis score: 18.3–18.4. | 2 arms: ivIgG vs. placebo. Follow-up: 28 days. | Stratified by center. Subgroups by gender, infection type, bacteremia, surgical vs. medical patients. | Based on 1992 ACCP/SCCM [50] sepsis definitions. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: 7-day mortality, APACHE II and sepsis score change (day 0–4), mech. vent. need, pulmonary function (A-a gradient), ICU/hospital survival and duration, AEs. | IV infusion: ivIgG (Polyglobin N, 5%). Day 0: 0.6 g/kg (12 mL/kg). Day 1: 0.3 g/kg (6 mL/kg) or placebo: 0.1% human albumin. | 28-day mortality: ivIgG 39.3% vs. placebo 37.3% (NS). Ventilation: ivIgG ↓ mech. vent. duration (~2 days in survivors). APACHE II and sepsis scores change: Slight improvement with ivIgG. Safety: NS difference (19 events total; 13 ivIgG vs. 6 placebo; p = 0.39). | Low |

| Wesoly et al., 1990, (Germany) [85] | RCT, open-label, prospective | Pentaglobin IVIG enriched in IgM and IgA | N = 35 patients with postoperative septic complications. IVIG: 18 patients (mean age: 44.7 ± 19 years). Placebo: 17 patients (mean age: 54.8 ± 16.9 years). M/F ratio IVIG: 15/3; control: 10/7. | 2 arms: Pentaglobin vs. control: no infusion. Follow-up daily until discharge or death (up to ~33 days). | NR. | Elebute & Stoner system [86] (modified), daily assessment, ≥12 points for inclusion. | Primary: Mortality, sepsis score, endotoxin titer. Secondary: Ventilation time, hospital LOS, antithrombin III plasma levels, AEs. | Pentaglobin 5 mL/kg IV on admission and next 2 days. | Mortality: Pentaglobin 44.4% (8/18) vs. control 76.5% (13/17). Mech. vent. days: Pentaglobin 9.9 ± 6.6 vs. control 12.8 ± 6.3. Total hospital stay: Pentaglobin 23.3 ± 5.8 days vs. control 25.8 ± 7.1 days. Sepsis score at discharge: Therapy 7.6 ± 3.8 vs. control 9.5 ± 2.7 (NS). Safety: No AEs reported. | Some concerns |

| Ziegler 1991, (USA, Canada, The Netherlands, Switzerland, UK) [70] | RCT, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled prospective | HA-1A Human mAb against endotoxin | N = 543 patients with sepsis syndrome and suspected G- infection. N = 200 with GNB analyzed. Mean age: ~62 yrs. Male: ~58–59%. Baseline APACHE II: ~25.7 (HA-1A), 23.6 (placebo). | 2 arms: HA-1A vs. placebo. Follow-up: Up to 28 days. | Stratified by shock vs. non-shock. Subgroups: APACHE II (>25 vs. ≤25), infection type (GNB, GP, fungal), adequacy of antibiotics/surgery. | SIRS: Temp > 38.3 °C or <35.6 °C, HR > 90 bpm, RR > 20 or mech. vent.; + hypotension (SBP < 90 mmHg or vasopressors) or ≥2 organ dysfunction signs (e.g., metabolic acidosis, hypoxemia, renal/hepatic failure) per Bone 1989 [49]-like criteria. | Primary: 28-day all-cause mortality. Secondary: Resolution of sepsis complications (shock, DIC, ARDS, renal/hepatic failure), hospital discharge survival, AEs. | Single IV of 100 mg HA-1A in 3.5 g albumin or placebo (3.5 g albumin alone). | Overall mortality: 39% (HA-1A) vs. 43% (placebo), (p = 0.24). Mortality in GNB: 30% (HA-1A) vs. 49% (placebo), (p = 0.014). Mortality in shock subgroup: 33% (HA-1A) vs. 57% (placebo), (p = 0.017). Stratified analysis: Benefit across APACHE II strata; faster resolution of sepsis complications (62% vs. 42%, p = 0.024); hospital discharge survival higher with HA-1A (63% vs. 48%, p = 0.038). Safety: NS AEs difference; no anti-HA-1A antibodies detected. | Low |

3.2.2. Endotoxin-Targeted Monoclonal Antibodies

3.2.3. Other Targeted Monoclonal Antibodies

3.3. Mortality Outcomes Following Polyclonal Antibody Intervention

3.3.1. Standard Intravenous Immunoglobulins (IVIG)

3.3.2. IgM-Enriched Immunoglobulin Preparations

3.4. Biomarker and Microbiological Indicators for Assessing Treatment Response

3.5. Evaluation of Critical Care Outcome Parameters and Disease Severity

3.5.1. Severity Score Dynamics

3.5.2. Organ Failure Prevention and Resolution

3.5.3. Support-Free Interval Metrics

3.5.4. Respiratory and Hemodynamic Recovery

3.5.5. Laboratory and Coagulation Trends

3.5.6. Hospitalization and Defervescence

3.5.7. Time-to-Event Outcomes

3.6. Safety and Tolerability of Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibody Therapies

3.7. Optimizing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibody Use in Targeted Sepsis Subgroups

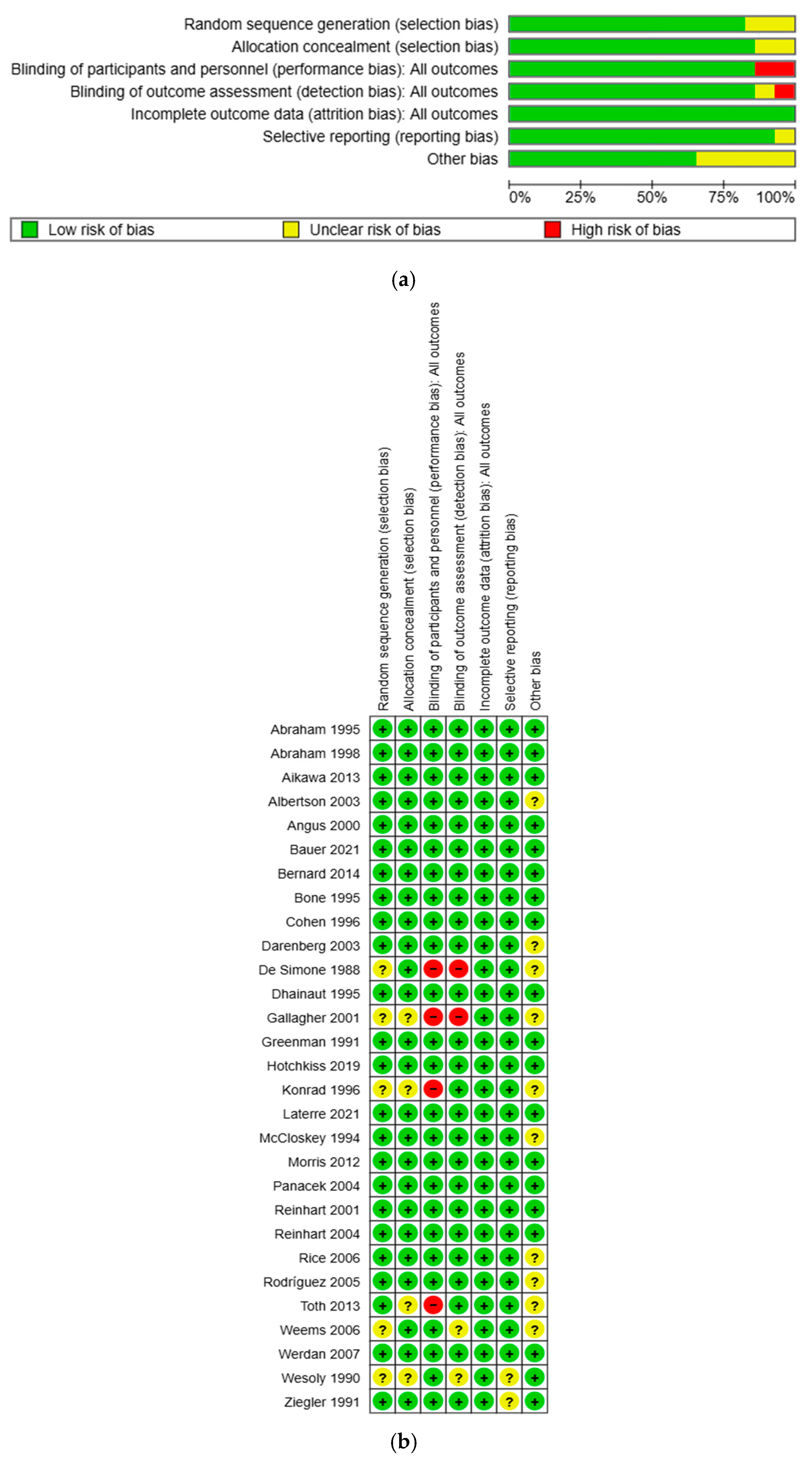

3.8. Risk of Bias Assessment—GRADE Assessment—Sensitivity Analysis

3.8.1. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.8.2. GRADE Assessment

3.8.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Immunopathological Targets and Antibody Therapies

4.2. Limitations of Antibody Therapies in Sepsis

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.4. Future Perspectives of Antibody-Based Therapies in Sepsis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- La Via, L.; Sangiorgio, G.; Stefani, S.; Marino, A.; Nunnari, G.; Cocuzza, S.; La Mantia, I.; Cacopardo, B.; Stracquadanio, S.; Spampinato, S.; et al. The Global Burden of Sepsis and Septic Shock. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 456–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sepsis. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/sepsis (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Rudd, K.E.; Johnson, S.C.; Agesa, K.M.; Shackelford, K.A.; Tsoi, D.; Kievlan, D.R.; Colombara, D.V.; Ikuta, K.S.; Kissoon, N.; Finfer, S.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Sepsis Incidence and Mortality, 1990–2017: Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2020, 395, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.J.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655, Erratum in Lancet 2022, 400, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann-Struzek, C.; Rudd, K. Challenges of Assessing the Burden of Sepsis. Med. Klin.-Intensivmed. Notfallmedizin 2023, 118, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, C.; Jones, T.M.; Hamad, Y.; Pande, A.; Varon, J.; O’Brien, C.; Anderson, D.J.; Warren, D.K.; Dantes, R.B.; Epstein, L.; et al. Prevalence, Underlying Causes, and Preventability of Sepsis-Associated Mortality in US Acute Care Hospitals. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.R.; Balraj, T.A.; Kempegowda, S.N.; Prashant, A. Multidrug-Resistant Sepsis: A Critical Healthcare Challenge. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefian, H.; Heublein, S.; Scherag, A.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Younis, M.Z.; Moerer, O.; Fischer, D.; Hartmann, M. Hospital-Related Cost of Sepsis: A Systematic Review. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, C.J.; Reynolds, M.A.; Sinha, M.; Gitlin, M.; Crouser, E. Epidemiology and Costs of Sepsis in the United States—An Analysis Based on Timing of Diagnosis and Severity Level. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, U.S. Government Report Reveals Annual Cost of Hospital Treatment of Sepsis Has Grown by $3.4 Billion|Sepsis Alliance. Available online: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb204-Most-Expensive-Hospital-Conditions.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Ting, Y.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Tan, Y.; Long, Y. From immune dysregulation to organ dysfunction: Understanding the enigma of Sepsis. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1415274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA—J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, R. DAMPs and DAMP-Sensing Receptors in Inflammation and Diseases. Immunity 2024, 57, 752–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wu, M. Pattern Recognition Receptors in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Hong, Q.; Li, C.; Zhu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Guo, K. Immunosenescence in Sepsis: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Aging Dis. 2025, 17, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delano, M.J.; Ward, P.A. The Immune System’s Role in Sepsis Progression, Resolution and Long-Term Outcome. Immunol. Rev. 2016, 274, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotis, P.; Chondropoulos, S.; Gkirkas, K.; Meletiadis, J.; Dimopoulou, I. Balanced Control of Both Hyper and Hypo-Inflammatory Phases as a New Treatment Paradigm in Sepsis. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, E312–E316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomer, J.S.; Green, J.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S. The Changing Immune System in Sepsis: Is Individualized Immuno-Modulatory Therapy the Answer? Virulence 2013, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wang, G.; Xie, J. Immune Dysregulation in Sepsis: Experiences, Lessons and Perspectives. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcato, G.; Zaboli, A.; Filippi, L.; Cipriano, A.; Ferretto, P.; Maggi, M.; Lucente, F.; Marchetti, M.; Ghiadoni, L.; Wiedermann, C.J. Endothelial Damage in Sepsis: The Interplay of Coagulopathy, Capillary Leak, and Vasoplegia—A Physiopathological Study. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, I.J.; Sjaastad, F.V.; Griffith, T.S.; Badovinac, V.P. Sepsis-Induced T Cell Immunoparalysis: The Ins and Outs of Impaired T Cell Immunity. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 1543–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.C.; Gentile, L.F.; Mathias, B.J.; Efron, P.A.; Brakenridge, S.C.; Mohr, A.M.; Moore, F.A.; Moldawer, L.L. Sepsis Pathophysiology, Chronic Critical Illness and PICS. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, S.M.; Lau, A.C.W.; Lam, R.P.K.; Yan, W.W. Clinical Management of Sepsis. Hong Kong Med. J. 2017, 23, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Gerlach, H.; Vogelmann, T.; Preissing, F.; Stiefel, J.; Adam, D. Mortality in Sepsis and Septic Shock in Europe, North America and Australia between 2009 and 2019-Results from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, Á.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Dias da Silva, D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Antimicrobial Resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macesic, N.; Uhlemann, A.-C.; Peleg, A.Y. Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Lancet 2025, 405, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, S.H.E.; Dorhoi, A.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Bartenschlager, R. Host-Directed Therapies for Bacterial and Viral Infections. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 17, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.C. Monoclonal Antibodies to Endotoxin in the Management of Sepsis. West. J. Med. 1993, 158, 393. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.A.; Brown, G.A.; Lewis, S.M.; Beale, R.; Treacher, D.F. Targeting Cytokines as a Treatment for Patients with Sepsis: A Lost Cause or a Strategy Still Worthy of Pursuit? Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 36, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, G.R.; Vincent, J.-L.; Laterre, P.-F.; LaRosa, S.P.; Dhainaut, J.-F.; Lopez-Rodriguez, A.; Steingrub, J.S.; Garber, G.E.; Helterbrand, J.D.; Ely, E.W.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Recombinant Human Activated Protein C for Severe Sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xigris (Drotrecogin Alfa (Activated)) to Be Withdrawn Due to Lack of Efficacy|European Medicines Agency (EMA). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/xigris-drotrecogin-alfa-activated-be-withdrawn-due-lack-efficacy (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Pan, B.; Sun, P.; Pei, R.; Lin, F.; Cao, H. Efficacy of IVIG Therapy for Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ton, A.M.P.; Kox, M.; Abdo, W.F.; Pickkers, P. Precision Immunotherapy for Sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharga, K.; Kumar, L.; Patel, S.K.S. Recent Advances in Monoclonal Antibody-Based Approaches in the Management of Bacterial Sepsis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Kim, N.Y.; Chung, C.; Park, D.; Kang, D.H.; Kim, D.K.; Yeo, M.K.; Sun, P.; Lee, J.E. IL-6 and PD-1 Antibody Blockade Combination Therapy Regulate Inflammation and T Lymphocyte Apoptosis in Murine Model of Sepsis. BMC Immunol. 2025, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geven, C.; Kox, M.; Pickkers, P. Adrenomedullin and Adrenomedullin-Targeted Therapy as Treatment Strategies Relevant for Sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 335741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, B.; Ghatol, A. Understanding How Monoclonal Antibodies Work. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572118/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Arumugham, V.B.; Rayi, A. Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG). In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554446/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Alejandria, M.M.; Lansang, M.A.D.; Dans, L.F.; Mantaring, J.B., III. Intravenous Immunoglobulin for Treating Sepsis, Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczak, D.; Kluge, S.; Nierhaus, A. Use of Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Sepsis Therapy—A Clinical View. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, S.F. Monoclonal Antibodies in ICU Management of Sepsis: Matters of Affinity, Targeting, and Specificity. Nurs. Res. Stud. 2024, 16, 3. Available online: https://crimsonpublishers.com/nrs/fulltext/NRS.000887.php (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Mahdizade Ari, M.; Amini, M.E.; Sholeh, M.; Zahedi Bialvaei, A. The Effect of Polyclonal and Monoclonal Based Antibodies as Promising Potential Therapy for Treatment of Sepsis: A Systematic Review. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 60–61, 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rosa, R.; Pietrosanti, M.; Luzi, G.; Salemi, S.; D’Amelio, R. Polyclonal Intravenous Immunoglobulin: An Important Additional Strategy in Sepsis? Eur. J. Intern Med. 2014, 25, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, R.; O’Dea, K.; Gordon, A. Immune Therapy in Sepsis: Are We Ready to Try Again? J. Intensive Care Soc. 2018, 19, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, W.S.; Wilson, M.C.; Nishikawa, J.; Hayward, R.S. The Well-Built Clinical Question: A Key to Evidence-Based Decisions. ACP J. Club 1995, 123, A12-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, M.M.; Fink, M.P.; Marshall, J.C.; Abraham, E.; Angus, D.; Cook, D.; Cohen, J.; Opal, S.M.; Vincent, J.-L.; Ramsay, G. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.C.; Fisher, C.J.; Clemmer, T.P.; Slotman, G.J.; Metz, C.A.; Balk, R.A. Sepsis Syndrome: A Valid Clinical Entity. Methylprednisolone Severe Sepsis Study Group. Crit. Care Med. 1989, 17, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, R.C.; Sibbald, W.J.; Sprung, C.L. The ACCP-SCCM Consensus Conference on Sepsis and Organ Failure. Chest 1992, 101, 1481–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE Guideline. Suspected Sepsis: Recognition, Diagnosis and Early Management. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR). Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/ (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S.; et al. GRADE Guidelines: 3. Rating the Quality of Evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, 4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.; Wunderink, R.; Silverman, H.; Perl, T.M.; Nasraway, S.; Levy, H.; Bone, R.; Wenzel, R.P.; Balk, R.; Allred, R.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Monoclonal Antibody to Human Tumor Necrosis Factor α in Patients With Sepsis Syndrome: A Randomized, Controlled, Double-Blind, Multicenter Clinical Trial. JAMA 1995, 273, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, E.; Anzueto, A.; Gutierrez, G.; Tessler, S.; San Pedro, G.; Wunderink, R.; Dal Nogare, A.; Nasraway, S.; Berman, S.; Cooney, R.; et al. Double-Blind Randomised Controlled Trial of Monoclonal Antibody to Human Tumour Necrosis Factor in Treatment of Septic Shock. Lancet 1998, 351, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertson, T.E.; Panacek, E.A.; MacArthur, R.D.; Johnson, S.B.; Benjamin, E.; Matuschak, G.M.; Zaloga, G.; Maki, D.; Silverstein, J.; Tobias, J.K.; et al. Multicenter Evaluation of a Human Monoclonal Antibody to Enterobacteriaceae Common Antigen in Patients with Gram-Negative Sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 31, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angus, D.C.; Birmingham, M.C.; Balk, R.A.; Scannon, P.J.; Collins, D.; Kruse, J.A.; Graham, D.R.; Dedhia, H.V.; Homann, S.; Macintyre, N. E5 Murine Monoclonal Antiendotoxin Antibody in Gram-Negative Sepsis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2000, 283, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.C.; Balk, R.A.; Fein, A.M.; Perl, T.M.; Wenzel, R.P.; Reines, H.D.; Quenzer, R.W.; Iberti, T.J.; Macintyre, N.; Schein, R.M.H.; et al. A Second Large Controlled Clinical Study of E5, a Monoclonal Antibody to Endotoxin: Results of a Prospective, Multicenter, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, J.; Fisher, C.; Sherman, B.; Munger, M.; Meyers, B.; Ellison, T.; Fischkoff, S.; Barchuk, W.T.; Teoh, L.; Velagapudi, R. A Multicenter, Open-Label, Prospective, Randomized, Dose-Ranging Pharmacokinetic Study of the Anti-TNF-α Antibody Afelimomab in Patients with Sepsis Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. Suppl. 2001, 27, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenman, R.L.; Schein, R.M.H.; Martin, M.A.; Wenzel, R.P.; Maclntyre, N.R.; Emmanuel, G.; Chmel, H.; Kohler, R.B.; McCarthy, M.; Plouffe, J.; et al. A Controlled Clinical Trial of E5 Murine Monoclonal IgM Antibody to Endotoxin in the Treatment of Gram-Negative Sepsis. JAMA 1991, 266, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Colston, E.; Yende, S.; Angus, D.C.; Moldawer, L.L.; Crouser, E.D.; Martin, G.S.; Coopersmith, C.M.; Brakenridge, S.; Mayr, F.B.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Sepsis: A Phase 1b Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Single Ascending Dose Study of Anti-PD-L1 (BMS-936559). Crit. Care Med. 2019, 47, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, R.V.; Straube, R.C.; Sanders, C.; Smith, S.M.; Smith, C.R. Treatment of Septic Shock with Human Monoclonal Antibody HA-1A: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 121, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, P.E.; Zeno, B.; Bernard, A.C.; Huang, X.; Das, S.; Edeki, T.; Simonson, S.G.; Bernard, G.R. A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Dose-Escalation Study to Assess the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of Single and Multiple Intravenous Infusions of AZD9773 in Patients with Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit. Care 2012, 16, R31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panacek, E.A.; Marshall, J.C.; Albertson, T.E.; Johnson, D.H.; Johnson, S.; MacArthur, R.D.; Miller, M.; Barchuk, W.T.; Fischkoff, S.; Kaul, M.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the Monoclonal Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Antibody F(Ab′) 2 Fragment Afelimomab in Patients with Severe Sepsis and Elevated Interleukin-6 Levels. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 2173–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, T.W.; Wheeler, A.P.; Morris, P.E.; Paz, H.L.; Russell, J.A.; Edens, T.R.; Bernard, G.R. Safety and Efficacy of Affinity-Purified, Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Ovine Fab for Injection (CytoFab) in Severe Sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 2006, 34, 2271–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, J.W.; Steinberg, J.P.; Filler, S.; Baddley, J.W.; Corey, G.R.; Sampathkumar, P.; Winston, L.; John, J.F.; Kubin, C.J.; Talwani, R.; et al. Phase II, Randomized, Double-Blind, Multicenter Study Comparing the Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Tefibazumab to Placebo for Treatment of Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2751–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, E.J.; Fisher, C.J., Jr.; Sprung, C.L.; Straube, R.C.; Sadoff, J.C.; Foulke, G.E.; Wortel, C.H.; Fink, M.P.; Dellinger, R.P.; Teng, N.N.H.; et al. Treatment of Gram-Negative Bacteremia and Septic Shock with HA-1A Human Monoclonal Antibody against Endotoxin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aikawa, N.; Takahashi, T.; Fujimi, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Yoshihara, K.; Ikeda, T.; Sadamitsu, D.; Momozawa, M.; Maruyama, T. A Phase II Study of Polyclonal Anti-TNF-α (AZD9773) in Japanese Patients with Severe Sepsis and/or Septic Shock. J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, G.R.; Francois, B.; Mira, J.P.; Vincent, J.L.; Dellinger, R.P.; Russell, J.A.; Larosa, S.P.; Laterre, P.F.; Levy, M.M.; Dankner, W.; et al. Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of Two Doses of the Polyclonal Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Fragment Antibody AZD9773 in Adult Patients with Severe Sepsis and/or Septic Shock: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase IIb Study. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Carlet, J. INTERSEPT: An International, Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Monoclonal Antibody to Human Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in Patients with Sepsis. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 24, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhainaut, J.F.A.; Vincent, J.L.; Richard, C.; Lejeune, P.; Martin, C.; Fierobe, L.; Stephens, S.; Ney, U.M.; Sopwith, M.; Mercat, A.; et al. CDP571, a Humanized Antibody to Human Tumor Necrosis Factor-α: Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Immune Response, and Influence of the Antibody on Cytokine Concentrations in Patients with Septic Shock. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 23, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.; Wiegand-Löhnert, C.; Grimminger, F.; Kaul, M.; Withington, S.; Treacher, D.; Eckart, J.; Willatts, S.; Bouza, C.; Krausch, D.; et al. Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of the Monoclonal Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Antibody-Fragment, MAK 195F, in Patients with Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 24, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.; Menges, T.; Gardlund, B.; Zwaveling, J.H.; Smithes, M.; Vincent, J.L.; Tellado, J.M.; Salgado-Remigio, A.; Zimlichman, R.; Withington, S.; et al. Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Antibody Fragment Afelimomab in Hyperinflammatory Response during Severe Sepsis: The RAMSES Study. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 29, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Weyland, A.; Marx, G.; Bloos, F.; Weber, S.; Weiler, N.; Kluge, S.; Diers, A.; Simon, T.P.; Lautenschläger, I.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Vilobelimab (IFX-1), a Novel Monoclonal Anti-C5a Antibody, in Patients with Early Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock—A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind, Multicenter, Phase IIa Trial (SCIENS Study). Crit. Care Explor. 2021, 3, E0577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, K.; Glück, T.; Ligtenberg, J.; Tschaikowsky, K.; Bruining, A.; Bakker, J.; Opal, S.; Moldawer, L.L.; Axtelle, T.; Turner, T.; et al. CD14 Receptor Occupancy in Severe Sepsis: Results of a Phase I Clinical Trial with a Recombinant Chimeric CD14 Monoclonal Antibody (IC14). Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, 1100–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laterre, P.F.; Pickkers, P.; Marx, G.; Wittebole, X.; Meziani, F.; Dugernier, T.; Huberlant, V.; Schuerholz, T.; François, B.; Lascarrou, J.B.; et al. Safety and Tolerability of Non-Neutralizing Adrenomedullin Antibody Adrecizumab (HAM8101) in Septic Shock Patients: The AdrenOSS-2 Phase 2a Biomarker-Guided Trial. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 47, 1284–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darenberg, J.; Ihendyane, N.; Sjölin, J.; Aufwerber, E.; Haidl, S.; Follin, P.; Andersson, J.; Norrby-Teglund, A. Intravenous Immunoglobulin G Therapy in Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome: A European Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, C.; Delogu, G.; Corbetta, G. Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Association with Antibiotics: A Therapeutic Trial in Septic Intensive Care Unit Patients. Crit. Care Med. 1988, 16, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Rello, J.; Neira, J.; Maskin, B.; Ceraso, D.; Vasta, L.; Palizas, F. Effects of High-Dose of Intravenous Immunoglobulin and Antibiotics on Survival for Severe Sepsis Undergoing Surgery. Shock 2005, 23, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, I.; Mikor, A.; Leiner, T.; Molnar, Z.; Bogar, L.; Szakmany, T. Effects of IgM-Enriched Immunoglobulin Therapy in Septic-Shock-Induced Multiple Organ Failure: Pilot Study. J. Anesth. 2013, 27, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werdan, K.; Pilz, G.; Bujdoso, O.; Fraunberger, P.; Neeser, G.; Schmieder, R.E.; Viell, B.; Marget, W.; Seewald, M.; Walger, P.; et al. Score-Based Immunoglobulin G Therapy of Patients with Sepsis: The SBITS Study*. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 35, 2693–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesoly, N.C.; Kipping, R. Grundmann. Immunglobulintherapie der postoperativen Sepsis [Immunoglobulin therapy of postoperative sepsis]. Z. Exp. Chir. Transplant. Kunstliche Organe 1990, 23, 213–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kellner, P.; Prondzinsky, R.; Pallmann, L.; Siegmann, S.; Unverzagt, S.; Lemm, H.; Dietz, S.; Soukup, J.; Werdan, K.; Buerke, M. Predictive Value of Outcome Scores in Patients Suffering from Cardiogenic Shock Complicating AMI: APACHE II, APACHE III, Elebute-Stoner, SOFA, and SAPS II. Med. Klin.-Intensivmed. Notfallmedizin 2013, 108, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarczak, D.; Kluge, S.; Nierhaus, A. Sepsis—Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Concepts. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 628302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignon, P.; Laterre, P.-F.; Daix, T.; François, B. New Agents in Development for Sepsis: Any Reason for Hope? Drugs 2020, 80, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Han, M.; Yi, R.; Kwon, S.; Dai, C.; Wang, R. Anti-TNF-α Therapy for Patients with Sepsis: A Systematic Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 68, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaillon, J.; Singer, M.; Skirecki, T. Sepsis Therapies: Learning from 30 Years of Failure of Translational Research to Propose New Leads. EMBO Mol. Med. 2020, 12, e10128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragle, B.E.; Bubeck Wardenburg, J. Anti-Alpha-Hemolysin Monoclonal Antibodies Mediate Protection against Staphylococcus Aureus Pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 2712–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinbockel, L.; Weindl, G.; Martinez-de-Tejada, G.; Correa, W.; Sanchez-Gomez, S.; Bárcena-Varela, S.; Goldmann, T.; Garidel, P.; Gutsmann, T.; Brandenburg, K. Inhibition of Lipopolysaccharide- and Lipoprotein-Induced Inflammation by Antitoxin Peptide Pep19-2.5. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, G.; Ma, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S. Advances in the Structural Characterization of Complexes of Therapeutic Antibodies with PD-1 or PD-L1. MAbs 2023, 15, 2236740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotchkiss, R.S.; Colston, E.; Yende, S.; Crouser, E.D.; Martin, G.S.; Albertson, T.; Bartz, R.R.; Brakenridge, S.C.; Delano, M.J.; Park, P.K.; et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Sepsis: A Phase 1b Randomized Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of Nivolumab. Intensive Care Med. 2019, 45, 1360–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François, B.; Lambden, S.; Fivez, T.; Gibot, S.; Derive, M.; Grouin, J.-M.; Salcedo-Magguilli, M.; Lemarié, J.; De Schryver, N.; Jalkanen, V.; et al. Prospective Evaluation of the Efficacy, Safety, and Optimal Biomarker Enrichment Strategy for Nangibotide, a TREM-1 Inhibitor, in Patients with Septic Shock (ASTONISH): A Double-Blind, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 2b Trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 11, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlot, G.; Zanchi, S.; Moro, E.; Tomasini, A.; Bixio, M. The Role of the Intravenous IgA and IgM-Enriched Immunoglobulin Preparation in the Treatment of Sepsis and Septic Shock. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Intravenous Immunoglobulin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 26, 513–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shao, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, X.; Mao, J.; Wei, Y.; Miao, C.; Zhang, H. Dysregulation of Neutrophil in Sepsis: Recent Insights and Advances. Cell Commun. Signal. 2025, 23, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, Y.; Chen, J.; Jha, A.; Lee, Y.; Ma, G.; Li, J.; Murao, A.; Wang, P.; Aziz, M. A Novel Molecule Targeting Neutrophil-Mediated B-1a Cell Trogocytosis Attenuates Sepsis-Induced Acute Lung Injury. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1597887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Qu, M.; Li, W.; Wu, D.; Cata, J.P.; Miao, C. Neutrophil, Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and Endothelial Cell Dysfunction in Sepsis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.-L.; van der Poll, T.; Marshall, J.C. The End of “One Size Fits All” Sepsis Therapies: Toward an Individualized Approach. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambden, S.; Grouin, J.-M.; Garaud, J.J.; Olivier, A.; Jolly, L.; Derive, M.; Cuvier, V.; Salcedo-Magguilli, M. Identification of the Biomarker Soluble TREM-1 as a Candidate for a Personalised Medicine Approach for Nangibotide Treatment of Septic Shock. Res. Sq. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arapis, A.; Panagiotopoulos, D.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. Recent Advances of Precision Immunotherapy in Sepsis. Burns Trauma 2025, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, O. Sepsis: An Overview of Current Therapies and Future Research. J. Clin. Pract. Res. 2025, 47, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angus, D.C.; Berry, S.; Lewis, R.J.; Al-Beidh, F.; Arabi, Y.; van Bentum-Puijk, W.; Bhimani, Z.; Bonten, M.; Broglio, K.; Brunkhorst, F.; et al. The Remap-Cap (Randomized Embedded Multifactorial Adaptive Platform for Community-Acquired Pneumonia) Study Rationale and Design. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BEATsep Consortium. Biomarkers Established to Stratify Sepsis Long-Term Adverse Effects to Improve Patients’ Health and Quality of Life. Horiz. Eur. Proj. 2023. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/101137484 (accessed on 13 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kalvelage, C.; Zacharowski, K.; Bauhofer, A.; Gockel, U.; Adamzik, M.; Nierhaus, A.; Kujath, P.; Eckmann, C.; Pletz, M.W.; Bracht, H.; et al. Personalized Medicine with IgGAM Compared with Standard of Care for Treatment of Peritonitis after Infectious Source Control (the PEPPER Trial): Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2019, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llitjos, J.-F.; Carrol, E.D.; Osuchowski, M.F.; Bonneville, M.; Scicluna, B.P.; Payen, D.; Randolph, A.G.; Witte, S.; Rodriguez-Manzano, J.; François, B. Enhancing Sepsis Biomarker Development: Key Considerations from Public and Private Perspectives. Crit. Care 2024, 28, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antcliffe, D.B.; Burrell, A.; Boyle, A.J.; Gordon, A.C.; McAuley, D.F.; Silversides, J. Sepsis Subphenotypes, Theragnostics and Personalized Sepsis Care. Intensive Care Med. 2025, 51, 756–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody Type/Target | Number of Patients (N) | Common and Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) | Comparative Safety Signal vs. Placebo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti–TNF-α mAbs | 5108 | Common: mild infusion reactions, transient fever/chills, lab changes (cytokine shifts and elevated total TNF from immune complexes). SAEs: rare hypersensitivity and ↑ anti–mouse antibody formation (≤5–20%, no clinical sequelae). | No excess SAEs vs. placebo. Adverse event rates similar; no increase in secondary infections or bleeding. Some anti–murine antibody formation but not clinically harmful. |

| Anti–endotoxin mAbs | 3202 | Common: mild infusion fever, chills, and skin reactions (~<10%). SAEs: hypersensitivity in 1–2% (reversible); HAMA up to 40% but without clinical consequence. | Comparable to placebo; organ toxicity not increased. Overall well tolerated despite high immunogenicity. |

| Other Targeted mAbs | 1219 | Common: infusion reactions and transient cytokine shifts. SAEs: none dose-limiting, no cytokine storm, and no ↑ secondary infections. | Equal to placebo in all trials. No new major safety signal. Checkpoint inhibitor and complement blockade considered safe in selected patients. |

| Polyclonal IVIG | 124 | Common: infusion reactions (headache, flushing, and fever) in 5–15%. SAEs: none consistent (no ↑ thrombosis, renal failure, or infections). | No difference vs. placebo in SAE incidence. |

| IgM-enriched IVIG | 669 | Common: transient fever, mild allergic reactions, and headache. SAEs: none reported. | Safety comparable to placebo. No signals of added harm. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goulas, K.; Müller, M.; Exadaktylos, A.K. Assessing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26188859

Goulas K, Müller M, Exadaktylos AK. Assessing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(18):8859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26188859

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoulas, Kyriakos, Martin Müller, and Aristomenis K. Exadaktylos. 2025. "Assessing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 18: 8859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26188859

APA StyleGoulas, K., Müller, M., & Exadaktylos, A. K. (2025). Assessing Monoclonal and Polyclonal Antibodies in Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(18), 8859. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26188859