Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance is a critical global health issue exacerbated by biofilm-associated infections that often resist conventional therapies. Photodithazine-mediated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (PDZ-aPDT) has emerged as a promising alternative, demonstrating a broad-spectrum antimicrobial efficacy against multidrug-resistant bacteria and fungi, including those in biofilms. This systematic review evaluates the efficacy, safety, and clinical applications of PDZ-aPDT by synthesizing evidence from preclinical and clinical studies. Databases including PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane were systematically searched, resulting in the inclusion of 13 studies for qualitative analysis. PDZ-aPDT consistently reduced the microbial burden in various models, including oral candidiasis, denture stomatitis, acne, and infections related to medical devices. Synergistic combinations with conventional antimicrobials and adjunctive therapies (e.g., DNase I) further enhanced its effectiveness. However, the evidence base remains limited by methodological variability, small sample sizes, and short follow-up periods. Future research should focus on rigorous clinical trials with standardized protocols and extended follow-up to establish definitive efficacy and safety profiles, facilitating a broader clinical implementation in combating antimicrobial resistance.

1. Introduction

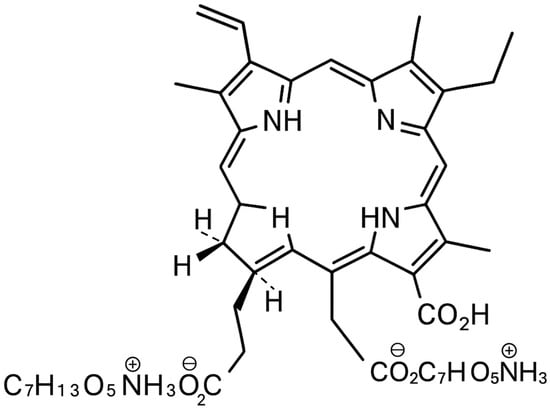

The rapid rise in antimicrobial resistance is recognized as one of the foremost global public health threats of the 21st century [1,2]. Conventional antibiotics and antifungal agents are increasingly compromised by the emergence and spread of multidrug-resistant bacteria and fungi, making the treatment of common infections ever more challenging and costly [3,4]. In addition to planktonic (free-floating) forms, many clinically relevant microorganisms persist within complex biofilms, structured communities encased in an extracellular matrix, that are inherently tolerant to traditional therapies and are a major cause of chronic and recurrent infections in the oral cavity, skin, and medical devices [5,6,7]. In the search for novel, effective alternatives to conventional antimicrobials, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has emerged as a promising non-antibiotic strategy. aPDT relies on the administration of a photosensitizing agent followed by illumination with light of a specific wavelength, which in the presence of oxygen leads to the generation of highly reactive singlet oxygen and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8,9,10]. These ROSs induce oxidative damage to microbial cell structures, ultimately resulting in cell death. Importantly, aPDT has a multi-targeted mechanism of action and does not promote the development of microbial resistance, making it attractive for the management of resistant and biofilm-associated infections [11,12]. Among the various photosensitizers explored for antimicrobial applications, Photodithazine (PDZ), a water-soluble chlorin e6 derivative, has garnered increasing attention for its potent photodynamic activity, favorable safety profile, and versatility across a range of clinical settings [13,14]. Figure 1 shows the structure of PDZ. It is a bis-N-methylglucamine salt of chlorin e6. PDZ is a mixture of di-N-methyl-D-glucosamine complexes, mainly containing Chl e6 (60%) along with Chl p6 and purpurins 7 and 18 [14].

Figure 1.

Structure of PDZ (image created by the author using Microsoft Office Tools, Microsoft Office 365).

PDZ is characterized by a high quantum yield of singlet oxygen upon red light activation (typically at 660 nm), good tissue penetration, and minimal cytotoxicity in the absence of light (dark toxicity). Its demonstrated antimicrobial spectrum is broad, encompassing Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, drug-resistant pathogens such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and fungal species including Candida albicans, both in planktonic and biofilm states [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Recent experimental and clinical studies have explored diverse applications of PDZ-aPDT, including the management of oral candidiasis, denture stomatitis, periodontitis, cutaneous infections such as acne, and device-related biofilms [17,18,19,20,21]. Innovative protocols combining PDZ-aPDT with adjuvant therapies, such as enzymes (DNase I), antifungals (fluconazole, nystatin), or antibiotics (metronidazole), have further expanded its potential, showing synergistic effects and an enhanced disruption of biofilms and extracellular polymeric matrices [17,18,19,20,21]. Moreover, PDZ’s clinical formulations (solutions and gels) allow for convenient topical application, increasing its translational potential [18,19,20]. Despite these advances, the available evidence regarding the efficacy, safety, and optimal use parameters for PDZ-aPDT remains fragmented across a variety of preclinical and clinical models. No comprehensive synthesis has yet to critically examine the range of experimental conditions, microbial targets, and clinical indications in which PDZ-aPDT has been evaluated, nor has the quality of existing studies been systematically assessed [17,18,19,20,21,22]. Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review is to comprehensively evaluate the efficacy and therapeutic applications of PDZ-aPDT across preclinical and clinical studies. This review summarizes the infectious models in which PDZ-aPDT has been tested, compares its antimicrobial effectiveness to standard therapies and alternative photosensitizers, and analyzes key parameters influencing outcomes such as photosensitizer concentration, light source specifications, and treatment protocols. Additionally, it assesses the safety profile, host tissue response, and risk of resistance, while identifying the potential of combinatorial and adjunctive strategies to improve clinical efficacy. By highlighting methodological strengths and limitations in the current literature, this review aims to clarify the role of PDZ as a photosensitizer, provide recommendations for optimal application, and support further research and clinical translation in the context of rising antimicrobial resistance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Focused Question

The PICO framework [23] was used to guide the research question: Among individuals affected by microbial infections (Population), can an aPDT utilizing PDZ as a photosensitizer (Intervention), when compared with standard antimicrobial therapies, other photosensitizers, or the absence of aPDT (Comparison), result in more favorable outcomes such as reduced microbial burden, increased antimicrobial effectiveness, or enhanced clinical recovery (Outcome)?

2.2. Search Strategy

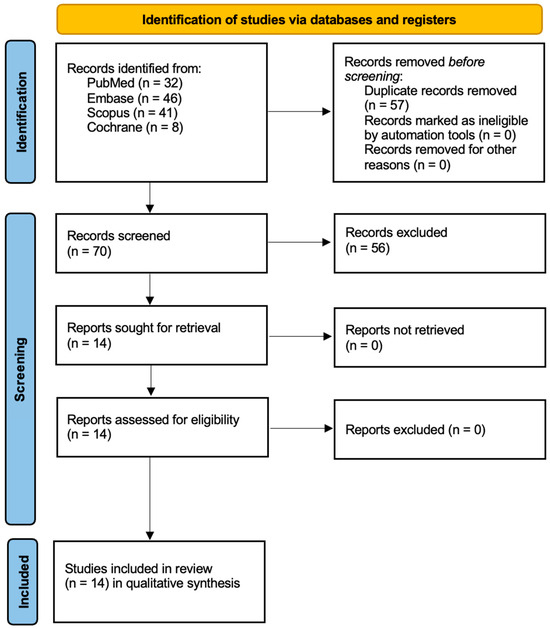

This review, registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD420251085052) [24], was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 [25] guidelines to maintain high standards of transparency and methodological quality. A systematic search was carried out across multiple electronic databases, PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library, to identify the relevant literature on the use of PDZ-aPDT for managing microbial infections. The comprehensive search strategy is illustrated in Figure 1. To capture all pertinent studies, a team of three reviewers independently applied a predefined set of search terms and MeSH descriptors focused on Photodithazine and antimicrobial photodynamic interventions. Only articles published in English were considered, regardless of the year of publication. The selection process involved a two-step screening: an initial title and abstract review followed by a full-text assessment, conducted independently by two reviewers using established inclusion and exclusion criteria (summarized in Table 1). Additionally, references of the included articles were manually screened to identify any further eligible studies not captured in the database search.

Table 1.

Search syntax used in the study.

2.3. Study Selection Process

To ensure methodological rigor and minimize the risk of bias, all retrieved studies were independently evaluated through a structured, multi-phase screening process by three authors. The initial screening of titles and abstracts was conducted using predefined inclusion criteria tailored to the review’s objectives. Discrepancies or conflicts in study selection were resolved through discussion and consensus to promote consistency and reliability in the decision-making process. The inclusion criteria were specifically designed to identify scientifically robust studies that investigated the antimicrobial efficacy of PDZ-aPDT. This review included experimental studies, either in vitro or in vivo, that examined the antimicrobial or biofilm-disruptive effects of PDZ as the primary photosensitizer within aPDT protocols. Eligible studies assessed outcomes such as bacterial or fungal load reduction, microbial viability, or the disruption of pathogenic biofilms. Studies exploring synergistic interactions between PDZ-aPDT and conventional antimicrobial agents, as well as those employing control groups (e.g., no treatment, placebo, or alternative photosensitizers), were also considered. Only studies that clearly reported the target microorganisms, described the treatment parameters, and included post-treatment evaluations of antimicrobial efficacy or biofilm response were included. Excluded from the review were non-peer-reviewed materials such as conference abstracts, case reports, editorials, opinion pieces, book chapters, and unpublished theses. Studies lacking scientific rigor, not written in English, or lacking relevant control or comparison groups were also excluded. In addition, research that did not use PDZ as the photosensitizer, studies evaluating unrelated technologies or therapies, and experiments involving non-pathogenic organisms or models lacking clinical relevance were not considered.

2.4. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

To ensure a transparent and unbiased selection process, the screening of titles and abstracts identified during the database search was independently carried out by three reviewers. Inter-reviewer reliability was quantified using Cohen’s kappa coefficient to objectively measure the consistency of study inclusion decisions [26]. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved through structured discussions aimed at reaching a consensus. This systematic approach was implemented to minimize the risk of selection bias, strengthen methodological integrity, and improve the overall reliability of the study identification process. The use of multiple independent reviewers and statistical agreement measures enhanced the rigor of this review on PDZ-aPDT and its therapeutic applications.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological rigor of each included study was independently assessed by three reviewers using a structured quality appraisal framework. This evaluation was based on a predefined checklist consisting of nine critical domains, as outlined in Table 2. For each criterion met, a score of 1 was assigned; unmet criteria were scored as 0. This binary scoring approach produced a cumulative quality score for each study, with total scores ranging from 0 to 9. Based on these totals, studies were categorized as having a high (0–3), moderate (4–6), or low (7–9) risk of bias. Any discrepancies in scoring among reviewers were discussed collaboratively, with input from a fourth reviewer when a consensus could not be reached. The assessment process was guided by principles from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [27]. Results of the risk-of-bias analysis are summarized in Table 2. No studies were excluded solely due to a high risk of bias. Of the nine studies included, seven were classified as low risk. Studies rated as moderate risk typically lacked adequate detail regarding control groups, statistical methods, or the transparent reporting of outcomes and funding disclosures. Evaluation criteria included the following: (1) clear documentation of the origin, purity, or synthesis method of PDZ used in the study; (2) description of the administration protocol, including concentration of PDZ, method of application, and incubation or exposure duration; (3) detailed reporting of the light source used in aPDT, including key parameters such as wavelength, energy dose (fluence), and exposure time; (4) evidence of microbial uptake or interaction with the photosensitizer prior to light activation, where applicable; (5) comprehensive description of experimental conditions, including microbial strain/species, culture methods, inoculation models, application site and environmental parameters; (6) inclusion of relevant control groups, such as untreated controls, light only, photosensitizer only, or comparator antimicrobials; (7) use of appropriate and clearly described statistical methods for analyzing antimicrobial efficacy or biofilm disruption outcomes; (8) transparent reporting of all measured outcomes, with no evidence of selective outcome reporting or unexplained missing data; and (9) disclosure of funding sources and any potential conflicts of interest that could influence the study design or interpretation.

Table 2.

Evaluation of methodological quality and bias risk across included studies, with criteria breakdown.

2.6. Data Extraction

Following consensus on the final set of studies for inclusion, three reviewers independently conducted data extraction using a predefined, standardized protocol to maintain accuracy and consistency. For each selected study, critical information was collected, including the first author, year of publication, study design, characteristics of the experimental model or microbial species, and descriptions of both experimental and control conditions. Where applicable, data on follow-up periods and key therapeutic outcomes, both primary and secondary, were compiled. Particular attention was given to the technical parameters of PDZ-aPDT, including the concentration of the photosensitizer, detailed specifications of the light source (e.g., wavelength, power density, and total energy dose), mode of administration, and any adjunctive interventions (e.g., antibiotics). Procedural aspects such as irradiation duration, application method, and frequency of treatment were also thoroughly documented to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons.

2.7. Study Selection

In Figure 2, the PRISMA flow diagram illustrates the process of the study selection for a systematic review. Initially, 127 records were identified through four databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane Library). After removing 57 duplicate records, 70 records remained for screening. Of these, 56 were excluded based on their titles or abstracts, leaving 14 reports to be retrieved and assessed for eligibility. All 14 reports were retrieved, and upon assessment, one report was excluded because it was a case report [41]. Ultimately, 13 studies were included in the qualitative synthesis for the review.

Figure 2.

Prisma 2020 flow diagram.

3. Results

3.1. Data Presentation

Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 offer a detailed and organized presentation of the results from the nine selected studies, encompassing an overall summary, important clinical outcomes, and essential methodological information, including study designs and descriptions of treatment groups.

Table 3.

A general overview of the included research.

Table 4.

Summary of principal results and study details.

Table 5.

aPDT characteristics.

Table 6.

Properties of Photodithazine as photosensitizer.

3.2. Overview of Study Characteristics

Table 3 presents an overview of the included studies.

3.3. Main Study Outcomes

Table 4 presents the main outcomes of the included studies.

3.4. Characteristics of Light Sources and Photosensitizer Used in aPDT

Table 5 summarizes the essential methodological aspects of aPDT as applied in the selected research, including a breakdown of light source specifications (wavelength, energy fluence) and detailed information on the use of PDZ as the photosensitizer, such as its administered concentration, delivery method, and pre-irradiation incubation period. Table 6 offers an in-depth overview of the chemical and functional attributes of PDZ relevant to its application as a photosensitizer in aPDT protocols.

4. Discussion

4.1. Results in the Context of Other Evidence

Photodithazine® is a second-generation photosensitizer comprising an N-dimethylglucamine salt derivative of chlorin e6, which improves water solubility, enhances cellular penetration, and prevents aggregation at concentrations up to 120 mg/L compared to first-generation photosensitizers [30,42,43,44,45]. Optimally absorbing at 660 nm, it efficiently penetrates deeper tissues and, when activated by red light, generates ROS through both Type I and Type II photodynamic mechanisms, causing oxidative damage to microbial cellular structures such as membranes, proteins, and nucleic acids [18,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Photodithazine® rapidly clears from the body, reducing skin photosensitivity effects compared to conventional photosensitizers like hematoporphyrin derivatives and localizes predominantly in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, disrupting critical cellular processes [42,43,47,48]. Its clinical effectiveness is strongly supported by randomized trials demonstrating superior microbiological efficacy in treating oral candidiasis, notably denture stomatitis, where PDZ-aPDT achieved bacterial load reductions of 1.98 log10 on the palate and 1.91 log10 on dentures, substantially surpassing conventional nystatin treatment [30,49,50].

Similarly, preclinical murine studies confirmed its superior performance, achieving complete remission of oral candidiasis lesions and a 3 log10 reduction in Candida albicans viability [35,36,51,52]. Recent studies have also revealed potential in acne treatment, with Photodithazine® combined with micro-LED technology effectively reducing acne lesions and key inflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin-1α, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor-α, and IL-8 [16]. Moreover, Photodithazine® exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, including efficacy against methicillin-resistant and -sensitive Staphylococcus aureus strains at low concentrations (75–100 mg/L), and importantly, it demonstrates effectiveness against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. In biofilm-associated infections, it effectively targets multispecies biofilms comprising Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, and Streptococcus mutans, achieving substantial reductions in colony viability, with an enhanced efficacy observed when combined with DNase I enzyme, resulting in a 4.26 log10 reduction for susceptible strains and a 2.89 log10 reduction for resistant strains [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Preclinical safety evaluations in porcine models have confirmed minimal toxicity, showing only mild inflammation without systemic adverse effects, rapid clearance, and negligible renal accumulation [51,52].

Comparative studies with conventional antimicrobials like nystatin have shown equivalent clinical outcomes but superior microbiological efficacy, although recurrence of infection indicates the necessity of maintenance or combination therapies. Despite promising therapeutic potential, Photodithazine® faces limitations including inadequate deep tissue light penetration, reduced efficacy under hypoxic conditions, and requirements for specialized equipment and trained personnel, potentially limiting broader clinical implementation, particularly in resource-constrained settings [53,54].

Regulatory approval for Photodithazine® has been obtained in Russia for various clinical applications including malignant tumors and antimicrobial therapy, though limited international acceptance highlights the need for standardized protocols and larger clinical trials [54,55,56]. Ongoing research continues to explore promising future directions, including combination therapies with DNase enzymes, antimicrobial peptides, conventional antibiotics, and advanced nanotechnology-based delivery systems to enhance targeting precision and minimize systemic exposure, as well as sophisticated micro-LED and fiber-optic technologies for precise and improved illumination [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Further exploration of fractionated light delivery and combined modalities like pulsed electric fields or ultrasound may overcome current limitations, expanding Photodithazine®’s therapeutic reach. Thus, Photodithazine® emerges as a valuable alternative or adjunctive approach to conventional antimicrobials, addressing global antimicrobial resistance challenges through its favorable safety profile, multi-target ROS-mediated mechanism, broad pathogen spectrum, and continued technological advancements in therapeutic application [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64].

4.2. Limitations of the Evidence

Despite encouraging results, the body of evidence supporting PDZ-aPDT is constrained by several notable limitations. First, significant heterogeneity exists among the included studies, particularly regarding experimental models (in vitro, animal, or clinical), photosensitizer concentrations, irradiation protocols, and outcome measures, making direct comparison and synthesis challenging. Most of the available research is preclinical, with only a few well-designed clinical trials, which restricts the ability to generalize findings to broader patient populations. Short follow-up periods and small sample sizes further limit insight into the long-term safety and sustained efficacy of PDZ-aPDT. Additionally, inconsistencies in the reporting of adverse events and variable definitions of clinical endpoints may result in the underestimation of potential risks or overestimation of therapeutic benefits. The lack of standardized control groups and limited direct comparisons with established antimicrobial therapies or alternative photosensitizers create further uncertainty regarding the relative efficacy of PDZ. Collectively, these limitations underscore the need for future large-scale, rigorously designed clinical trials with standardized protocols and long-term follow-ups to robustly determine the clinical value and safety profile of PDZ-aPDT.

4.3. Limitations of the Review Process

Although this systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines and incorporated rigorous methodological safeguards, several limitations of the review process should be acknowledged. Restricting the search to English-language publications may have introduced language bias and led to the exclusion of relevant studies published in other languages. The omission of gray literature, such as conference proceedings, dissertations, and unpublished data, may also have contributed to publication bias, potentially skewing results toward studies with positive or significant findings. Additionally, the relatively small number of eligible studies, many of which were preclinical, limits the ability to draw robust conclusions applicable to clinical practice. The marked heterogeneity among study designs, intervention protocols, and outcome measures further precluded the possibility of conducting a quantitative meta-analysis. While multiple independent reviewers participated in screening and data extraction to reduce selection bias, the use of subjective quality assessment tools introduces the potential for reviewer bias. Lastly, the variability in reporting and lack of long-term data in many included studies limits the overall strength and generalizability of the review’s findings. A major limitation of this systematic review is the heavy reliance on studies conducted by Dr. Pavarina’s research group [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,40], which accounted for most of the included articles. The predominance of data generated using similar methodologies and by overlapping teams of investigators introduce an inherent risk of methodological and publication bias. This concentration of evidence from a single research network may limit the generalizability of the findings and could reduce the robustness and external validity of the conclusions drawn. Although these studies provide valuable and consistent data, the lack of broader independent validation underscores the need for future research from multiple centers and diverse clinical environments to confirm and expand upon these results. Therefore, the present review should be interpreted primarily as a call for further independent studies rather than as a basis for definitive clinical recommendations. Broader multicenter investigations are needed to validate and extend these findings before widespread clinical adoption can be advised.

4.4. Implications for Practice, Policy, and Future Research

The findings of this systematic review highlight significant implications for clinical practice, policy-making, and future research. Clinically, PDZ-aPDT presents a promising alternative or adjunct treatment for multidrug-resistant infections, biofilm-associated conditions, and superficial microbial infections such as oral candidiasis, denture stomatitis, and acne. Practitioners should consider integrating PDZ-aPDT into their treatment protocols while carefully selecting parameters based on available evidence. From a policy perspective, there is a critical need to fund and promote large-scale clinical trials to establish standardized guidelines and streamline regulatory approval processes for Photodithazine-based therapies, considering the urgency of antimicrobial resistance. Additionally, policies supporting specialized training in photodynamic therapy techniques could improve implementation efficacy. Future research should prioritize addressing gaps identified in this review through rigorous randomized controlled trials with larger patient populations, standardized treatment protocols, and investigations into optimal therapeutic parameters. Exploring the potential synergistic effects of PDZ-aPDT with other antimicrobials, DNase enzymes, and advanced delivery systems such as nanotechnology is also essential. Research aimed at overcoming current technical limitations, such as tissue penetration and efficacy in hypoxic environments, will further enhance the broader clinical applicability of PDZ-aPDT, thereby advancing patient care and public health outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review demonstrates that PDZ-aPDT is a promising therapeutic strategy with the potential for managing multidrug-resistant microbial infections, biofilm-associated conditions, and superficial infections including oral candidiasis, denture stomatitis, acne, and device-related infections. PDZ-aPDT exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, favorable safety profiles, and minimal risk of inducing microbial resistance. Nevertheless, the existing body of evidence is limited by methodological heterogeneity, predominantly preclinical data, small sample sizes, and a lack of standardized treatment protocols. Thus, further high-quality clinical trials with rigorous methodology, larger patient populations, and long-term follow-up are essential to confirm efficacy, optimize treatment parameters, and ensure safety. Continued exploration into adjunctive and synergistic therapies, innovative delivery systems, and technological improvements for deeper tissue penetration and enhanced effectiveness under hypoxic conditions will further solidify the role of PDZ-aPDT as a valuable adjunct or alternative to conventional antimicrobials, effectively addressing the global challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and J.F.-R.; Methodology, J.A.-D., D.S. and K.G.-L.; Software, J.F.-R. and R.W.; Formal analysis, J.A.-D., K.G.-L., J.F.-R., D.S. and R.W.; Investigation, J.A.-D., K.G.-L. and R.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, J.F.-R., D.S., K.G.-L. and R.W.; Writing—review and editing, J.F.-R., J.A.-D., K.G.-L., D.S. and R.W.; Supervision, J.A.-D., D.S. and K.G.-L.; Funding acquisition, D.S. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance, A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coque, T.M.; Cantón, R.; Pérez-Cobas, A.E.; Fernández-de-Bobadilla, M.D.; Baquero, F. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Global Health Network, Known Unknowns and Challenges for Efficient Responses in the 21st Century. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muteeb, G.; Rehman, M.T.; Shahwan, M.; Aatif, M. Origin of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance, and Their Impacts on Drug Development, A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, M.; Antunes, W.; Mota, S.; Madureira-Carvalho, Á.; Dinis-Oliveira, R.J.; Dias da Silva, D. An Overview of the Recent Advances in Antimicrobial Resistance. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlan, R.M.; Costerton, J.W. Biofilms, Survival Mechanisms of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 15, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, M.; Nobile, C.J. Candida albicans Biofilms, Development, Regulation, and Molecular Mechanisms. Microbes Infect. 2016, 18, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; Fidanza, A.; Giannetti, A.; Ciuffoletti, A.; Logroscino, G.; Romanò, C.L. Correction: Drago et al. Bacteria Living in Biofilms in Fluids, Could Chemical Antibiofilm Pretreatment of Culture Represent a Paradigm Shift in Diagnostics? Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, R.; Zaat, S.A.J.; Breukink, E.; Heger, M. Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy, Overview of a Promising Approach to Fight Antibiotic-Resistant Bacterial Infections. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2015, 1, 140–167. [Google Scholar]

- Youf, R.; Müller, M.; Balasini, A.; Thétiot, F.; Müller, M.; Hascoët, A.; Jonas, U.; Schönherr, H.; Lemercier, G.; Montier, T.; et al. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy, Latest Developments with a Focus on Combinatory Strategies. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, S.; Partoazar, A.; Chiniforush, N.; Goudarzi, R. The Potential Application of Natural Photosensitizers Used in Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Against Oral Infections. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashef, N.; Hamblin, M.R. Can Microbial Cells Develop Resistance to Oxidative Stress in Antimicrobial Photodynamic Inactivation? Drug Resist. Updates 2017, 31, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Silva, L.B.B.D.; Castilho, I.G.; Souza Silva, F.A.D.; Ghannoum, M.; Garcia, M.T.; Carmo, P.H.F.D. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy for Superficial, Skin, and Mucosal Fungal Infections, An Update. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M.; Szymczyk, J.; Pawska, A.; Wysocki, M.; Janiak, D.; Ziental, D.; Ptaszek, M.; Güzel, E.; Sobotta, L. Chlorin Activity Enhancers for Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2025, 30, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, L.; Bosco Sde, M.; da Silva, N.F., Jr.; Kurachi, C. Photodynamic Therapy for Pythiosis. Vet. Dermatol. 2013, 24, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.C.; Pinto, J.G.; Pereira, A.H.C.; Soares, C.P.; Raniero, L.J.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Photodithazine Photodynamic Effect on Viability of 9L/lacZ Gliosarcoma Cell Line. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1245–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Kapłon, K.; Kotucha, K.; Moś, M.; Skaba, D.; Kawczyk-Krupka, A.; Wiench, R. Hypocrellin-Mediated PDT: A Systematic Review of Its Efficacy, Applications, and Outcomes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turubanova, V.D.; Balalaeva, I.V.; Mishchenko, T.A.; Catanzaro, E.; Alzeibak, R.; Peskova, N.N.; Efimova, I.; Bachert, C.; Mitroshina, E.V.; Krysko, O.; et al. Immunogenic Cell Death Induced by a New Photodynamic Therapy Based on Photosens and Photodithazine. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santos Vitorio, G.D.; de Almeida, R.M.S.; Pinto, J.G.; Fontana, L.C.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Analysis of the Effects of Photodynamic Therapy with Photodithazine on the Treatment of 9l/lacZ Cells, In Vitro Study. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, G.; Mokrzyński, K. Concentration-Dependent Photoproduction of Singlet Oxygen by Common Photosensitizers. Molecules 2025, 30, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzá, H.H.; Silva, L.V.; Moriyama, L.T.; Bagnato, V.S.; Kurachi, C. Evaluation of Vascular Effect of Photodynamic Therapy in Chorioallantoic Membrane Using Different Photosensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 138, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Nd:YAG Laser in Polymicrobial Root Canal Infections: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Pereira, C.A.; Gorayb-Pereira, A.L.; Jordão, C.C.; Bitencourt, G.P.; Cilli, E.M.; Pavarina, A.C. Efficiency of the Extracellular Polymeric Matrix Disruptor Zerumbone in Combination with Photodithazine® in the Photodynamic Inactivation of Monospecies Biofilms. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, C.; Adams, M.B.; Owens, T.; Keitz, S.; Fontelo, P. Utilization of the PICO Framework to Improve Searching PubMed for Clinical Questions. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2007, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; Shamseer, L.; Tricco, A.C. Registration of Systematic Reviews in PROSPERO, 30,000 Records and Counting. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement, An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method Agreement Analysis, A Review of Correct Methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M. Welch Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.4. Cochrane. 2023. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Abreu-Pereira, C.A.; Gorayb-Pereira, A.L.; Jordão, C.C.; Paro, C.B.; Barbugli, P.A.; Pavarina, A.C. Zerumbone Enhances the Photodynamic Effect Against Biofilms of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida albicans Clinical Isolates. J. Dent. 2025, 155, 105631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Carmello, J.C.; Alonso, G.C.; Mima, E.G.O.; Bagnato, V.S.; Pavarina, A.C. A Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating Photodithazine-Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as a Treatment for Denture Stomatitis. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 32, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmello, J.C.; Alves, F.; GBasso, F.; de Souza Costa, C.A.; Bagnato, V.S.; de Oliveira Mima, E.G.; Pavarina, A.C. Treatment of Oral Candidiasis Using Photodithazine®-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.M.; Klein, M.I.; Jordão, C.C.; Carmello, J.C.; Bellini, A.; Pavarina, A.C. Successive Applications of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Effects the Susceptibility of Candida albicans Grown in Medium with or Without Fluconazole. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 32, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.M.; Klein, M.I.; Ferrisse, T.M.; Medeiros, K.S.; Jordão, C.C.; Bellini, A.; Pavarina, A.C. The Effect of Sub-Lethal Successive Applications of Photodynamic Therapy on Candida albicans Biofilm Depends on the Photosensitizer. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, C.C.; de Sousa, T.V.; Klein, M.I.; Dias, L.M.; Pavarina, A.C.; Carmello, J.C. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Reduces Gene Expression of Candida albicans in Biofilms. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, C.C.; Klein, M.I.; Barbugli, P.A.; Mima, E.G.D.O.; de Sousa, T.V.; Ferrisse, T.M.; Pavarina, A.C. DNase Improves the Efficacy of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Candidiasis Induced with Candida albicans. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1274201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, C.C.; Klein, M.I.; Barbugli, P.A.; Ferrisse, T.M.; de Moraes, J.C.G.; Pavarina, A.C. The Association of DNase I with Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Affects Candida albicans Gene Expression and Promotes Immunomodulatory Effects in Mice with Candidiasis. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, Z.; Lee, J.-B. Photodynamic Effects of Topical Photosensitizer, Photodithazine Using Micro-LED for Acne Bacteria Induced Inflammation. Ann. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quishida, C.C.C.; Mima, E.G.O.; Dovigo, L.N.; Jorge, J.H.; Bagnato, V.S.; Pavarina, A.C. Photodynamic Inactivation of a Multispecies Biofilm Using Photodithazine® and LED Light After One and Three Successive Applications. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 2303–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, B.M.N.; Pinto, J.G.; Pereira, A.H.C.; Miñán, A.G.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Efficiency of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Photodithazine® on MSSA and MRSA Strains. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, B.M.N.; Miñán, A.G.; Brambilla, I.R.; Pinto, J.G.; Garcia, M.T.; Junqueira, J.C.; Ferreira-Strixino, J. Effects of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Photodithazine® on Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Studies in Biofilms and Experimental Model with Galleria mellonella. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2024, 252, 112860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, L.J.; de Avila, E.D.; Klein, M.I.; Panariello, B.H.D.; Spolidorio, D.M.P.; Pavarina, A.C. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Alone or in Combination with Antibiotic Local Administration Against Biofilms of Fusobacterium nucleatum and Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2018, 188, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Alonso, G.C.; Carmello, J.C.; Mima, E.G.O.; Bagnato, V.S.; Pavarina, A.C. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Photodithazine® in the Treatment of Denture Stomatitis, A Case Report. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, H.; Feng, C.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. A Chlorin e6 Derivative-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy for Mild to Moderate Acne, A Prospective, Single-Blind, Randomized, Split-Face Controlled Study. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 49, 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, A.; Matveev, L.; Moiseev, A.; Sedova, E.; Loginova, M.; Karabut, M.; Kuznetsova, I.; Levchenko, V.; Grebenkina, E.; Gamayunov, S.; et al. Multimodal OCT Control for Early Histological Signs of Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus Recurrence After Systemic PDT, Pilot Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.; Menezesa, P.F.C.; Sibatac, C.H.; Allison, R.R.; Zucoloto, S.; Castro e Silva, O., Jr.; Bagnato, V.S. Can Efficiency of the Photosensitizer Be Predicted by Its Photostability in Solution? Laser Phys. 2009, 19, 1932–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łopaciński, M.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Niemczyk, W.; Skaba, D.; Wiench, R. Riboflavin- and Hypericin-Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy as Alternative Treatments for Oral Candidiasis, A Systematic Review. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiench, R.; Nowicka, J.; Pajączkowska, M.; Kuropka, P.; Skaba, D.; Kruczek-Kazibudzka, A.; Kuśka-Kiełbratowska, A.; Grzech-Leśniak, K. Influence of Incubation Time on Ortho-Toluidine Blue Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Directed Against Selected Candida Strains—An In Vitro Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubizna, M.; Dawiec, G.; Wiench, R. Efficacy of Curcumin-Mediated Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy on Candida spp., A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Tkaczyk, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Zawilska, A.; Wiench, R. Enhancing Root Canal Disinfection with Er:YAG Laser, A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembicka-Mączka, D.; Kępa, M.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Matys, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Wiench, R. Evaluation of the Disinfection Efficacy of Er: YAG Laser Light on Single-Species Candida Biofilms—An In Vitro Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quishida, C.C.; Carmello, J.C.; Mima, E.G.; Bagnato, V.S.; Machado, A.L.; Pavarina, A.C. Susceptibility of Multispecies Biofilm to Photodynamic Therapy Using Photodithazine®. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Xuan, Y.; Koide, Y.; Zhiyentayev, T.; Tanaka, M.; Hamblin, M.R. Type I and Type II Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy, An In Vitro Study on Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacteria. Lasers Surg. Med. 2012, 44, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, T.J.; Gomer, C.J.; Henderson, B.W.; Jori, G.; Kessel, D.; Korbelik, M.; Moan, J.; Peng, Q. Photodynamic Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 889–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, W.; Shi, X.; Li, C. A Hypoxia-Activatable Theranostic Agent with Intrinsic Endoplasmic Reticulum Affinity and Type-I Photosensitivity. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 3835–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mima, E.G.; Vergani, C.E.; Machado, A.L.; Massucato, E.M.; Colombo, A.L.; Bagnato, V.S.; Pavarina, A.C. Comparison of Photodynamic Therapy Versus Conventional Antifungal Therapy for the Treatment of Denture Stomatitis, A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E380–E388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rai, A.; Misra, S.R.; Panda, S.; Sokolowski, G.; Mishra, L.; Das, R.; Lapinska, B. Nystatin Effectiveness in Oral Candidiasis Treatment, A Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Life 2022, 12, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dovigo, L.N.; Carmello, J.C.; de Souza Costa, C.A.; Vergani, C.E.; Brunetti, I.L.; Bagnato, V.S.; Pavarina, A.C. Curcumin-Mediated Photodynamic Inactivation of Candida albicans in a Murine Model of Oral Candidiasis. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostinis, P.; Berg, K.; Cengel, K.A.; Foster, T.H.; Girotti, A.W.; Gollnick, S.O.; Hahn, S.M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Juzeniene, A.; Kessel, D.; et al. Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer, An Update. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011, 61, 250–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, L.; Li, J.; Luo, Y.; Guo, T.; Zhang, C.; Ou, S.; Long, Y.; Hu, Z. Recent Advances in Strategies for Addressing Hypoxia in Tumor Photodynamic Therapy. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mallidi, S.; Anbil, S.; Bulin, A.L.; Obaid, G.; Ichikawa, M.; Hasan, T. Beyond the Barriers of Light Penetration, Strategies, Perspectives and Possibilities for Photodynamic Therapy. Theranostics 2016, 6, 2458–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hamblin, M.R. Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer, What’s Past is Prologue. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gubarkova, E.V.; Feldchtein, F.I.; Zagaynova, E.V.; Gamayunov, S.V.; Sirotkina, M.A.; Sedova, E.S.; Kuznetsov, S.S.; Moiseev, A.A.; Matveev, L.A.; Zaitsev, V.Y.; et al. Optical Coherence Angiography for Pre-Treatment Assessment and Treatment Monitoring Following Photodynamic Therapy, A Basal Cell Carcinoma Patient Study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Jin, F.; Xiao, J.; Lan, N.; Xu, Z.; Yue, X.; Li, Z.; Li, C.; Cao, D.; et al. Fiber-Optic Drug Delivery Strategy for Synergistic Cancer Photothermal-Chemotherapy. Light Sci. Appl. 2024, 13, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overchuk, M.; Weersink, R.A.; Wilson, B.C.; Zheng, G. Photodynamic and Photothermal Therapies, Synergy Opportunities for Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 7436–7489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiench, R.; Kuśka-Kiełbratowska, A.; Kępa, M.; Grzech-Leśniak, Z.; Jabłoński, M.; Kiryk, J.; Grzech-Leśniak, K.; Skaba, D. Comparison of the Efficacy of Simple and Combined Oral Rinses with Chlorhexidine Digluconate Against Selected Bacterial and Yeast Species, An In Vitro Study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).