The Senescence of Cut Daffodil Flowers Correlates with Programmed Cell Death Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

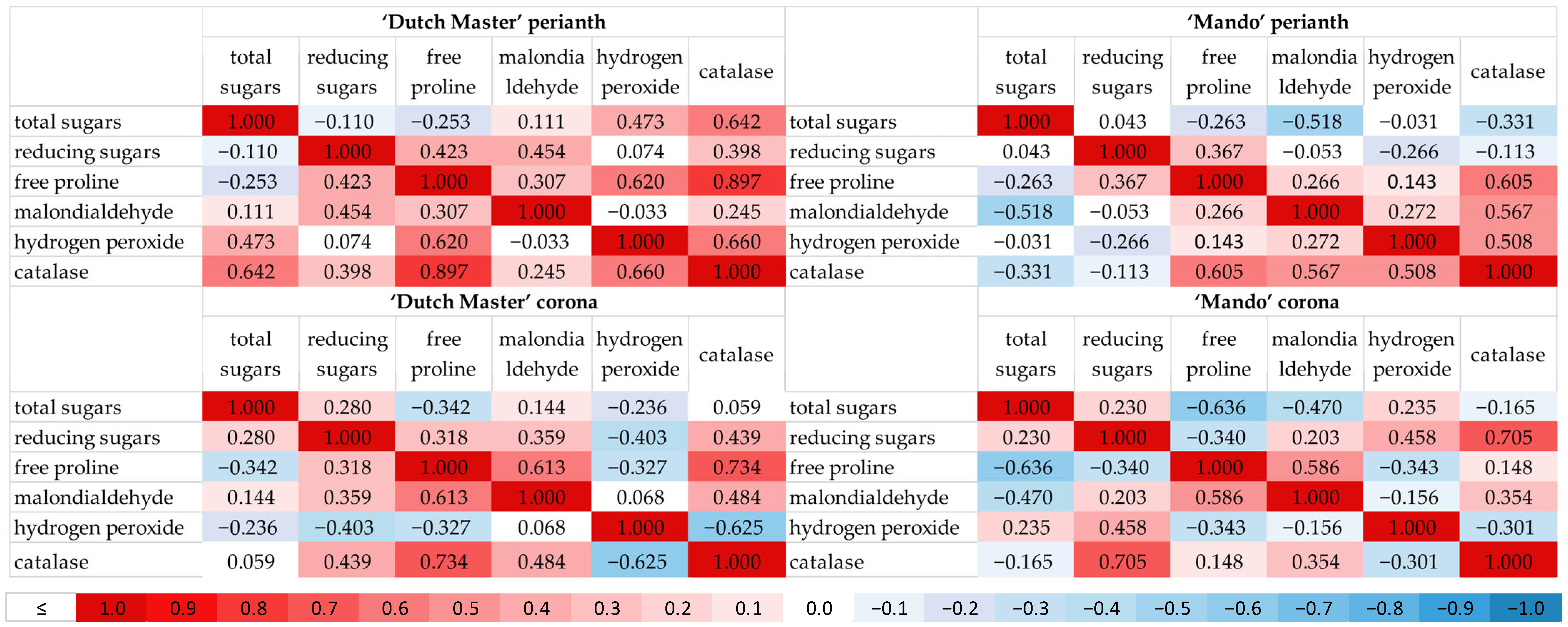

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Biochemical Assays

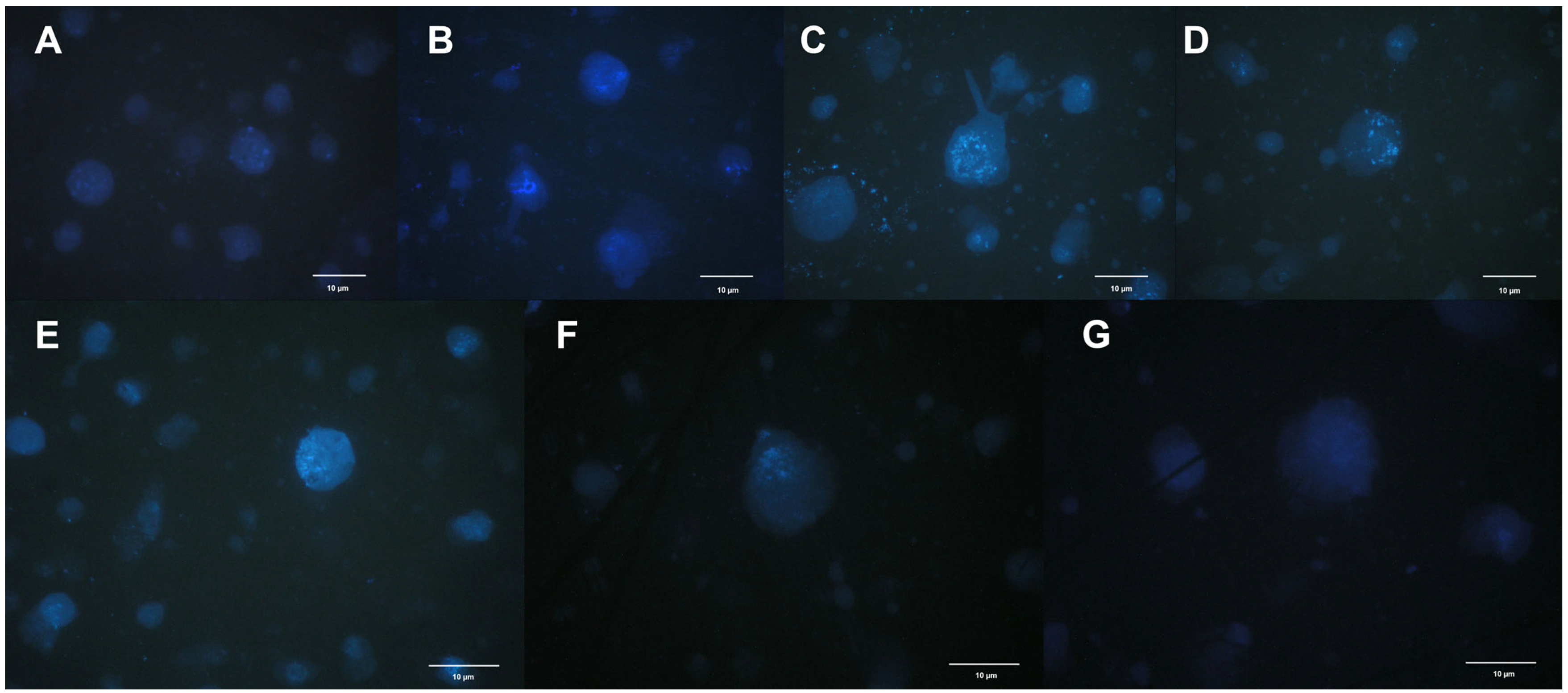

4.2. Nuclear Morphology

4.3. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DW | Dry Weight |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| PCD | Programmed Cell Death |

References

- Rabiza-Świder, J.; Skutnik, E.; Jędrzejuk, A.; Sochacki, D. Effect of preservatives on senescence of cut daffodil (Narcissus L.) flowers. J. Horticultural Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 95, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, B. Regulation of cell death in flower petals. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 44, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, D.A.; Steele, B.C.; Reid, M.S. Identifications of genes associated with perianth senescence in daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus L. ‘Dutch Master’). Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.J. Programmed cell death in floral organs: How and why do flowers dye? Ann. Bot. 2006, 97, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Ge, H.; Hoeberichts, F.A.; Visser, P.B. Programmed cell death in relation to petal senescence in ornamental plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2005, 47, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, K.; Yamada, T.; Ichimura, K. Morphological changes in senescing petal cells and the regulatory mechanism of petal senescence. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 5909–5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeberichts, F.A.; de Jong, A.J.; Woltering, E.J. Apoptotic-like death marks the early stages of gypsophila (Gypsophila paniculata) petal senescence. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2005, 35, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, W.G.; Balk, P.A.; van Houwelingen, A.M.; Hoeberichts, F.A.; Hall, R.D.; Vorst, O.; van der Schoot, C.; van Wordragen, M.F. Gene expression during anthesis and senescence in iris flowers. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003, 53, 854–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagstaff, C.; Malcolm, P.; Rafiq, A.; Leverentz, M.; Griffiths, G.; Thomas, B.; Stead, A.; Rogers, H. Programmes cell death (PCD) processes begin extremely early in Alstroemeria petal senescence. New Phytol. 2003, 160, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejuk, A.; Rochala, J.; Dolega, M.; Łukaszewska, A. Comparison of petal senescence in forced and unforced common lilac flowers during their postharvest life. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013, 35, 1785–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiza-Świder, J.; Rochala, J.; Jędrzejuk, A.; Skutnik, E.; Łukaszewska, A. Symptoms of programmed cell death in intact and cut flowers of clematis and the effect of a standard preservative on petal senescence in two cultivars differing in flower longevity. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 118, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiza-Świder, J.; Skutnik, E.; Jędrzejuk, A.; Rochala-Wojciechowska, J. Nanosilver and sucrose delay the senescence of cut snapdragon flowers. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2020, 165, 111165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panavas, T.; Bubinstein, B. Oxidative events during programmed cell death of daylily (Hemerocallis hybrida) petals. Plant Sci. 1998, 133, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Ichimura, K.; van Doorn, W.G. DNA degradation and nuclear degeneration during programmed cell death in petals of Antirrhinum, Argyranthemum, and Petunia. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 57, 3543–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahri, W. Senescence: Concepts and synonyms. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2011, 10, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahri, W.; Tahir, I. Flower senescence-strategies and some associated events. Bot. Rev. 2011, 77, 152–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, A.M.; Laushman, J.M. Specialty Cut flowers; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA, 2003; pp. 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D.A.; Reid, M.S. Extending the Vase Life of Narcissus Flowers. 2005, pp. 18–25. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283083286_Extending_the_vase_life_of_Narcissus_flowers (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- El-Sayed, I.M.; El-Ziat, R.A.; Othman, E.Z. Chitosan and copper nanoparticles in vase solutions elevate the quality and longevity of cut tulips, setting a new standard for sustainability in floriculture. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pun, U.K.; Ichimura, K. Role of sugars in senescence and biosynthesis of ethylene in cut flowers. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2003, 37, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eason, J.R.; de Vré, L.A.; Somerfield, S.D.; Heyes, J.A. Physiological changes associated with Sandersonia aurantiaca flower senescence in response to sugar. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 1997, 12, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Pal, M.; Srivastava, G.C. Proline metabolism in senescing rose petals (Rosa hybrida L. ‘First Red’). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Srivastava, G.C.; Dixit, K. Hormonal regulation of flower senescence in roses (Rosa hybrida L.). Plant Growth Regul. 2008, 55, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiza-Świder, J.; Skutnik, E.; Jędrzejuk, A. The effect of a sugar-containing preservative on senescence-related processes in cut clematis flowers. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2019, 47, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Becker, D.F. Connecting proline metabolism and signalling pathways in plant senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiza-Świder, J.; Skutnik, E.; Jędrzejuk, A.; Łukaszewska, A. Postharvest treatments improve quality of cut peony flowers. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, S.; Altaf, F.; Farooq, S.; ul Haq, A.; Lateef Lone, M.; Tahir, I. Is proline the quintessential sentinel of plants? A case study of postharvest flower senescence in Dianthus chinensis L. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bartoli, C.G.; Simontacchi, M.; Guiamet, J.J.; Montaldi, E.; Puntarulo, S. Antioxidant enzymes and lipid peroxidation during aging of Chrysanthemum morifolium RAM petals. Plant Sci. 1995, 104, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.J.; Yang, L.Q.; Sun, N.L.; Li, J.; Fang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.P. Physiological and antioxidant enzyme gene expression analysis reveals the improved tolerance to drought stress of the somatic hybrid offspring of Brassica napus and Sinapis alba at vegetative stage. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2016, 38, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Cheng, M.; Tang, W.; Liu, D.; Zhou, S.; Meng, J.; Tao, J. Nano-silver modifies the vase life of cut herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) flowers. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 1001–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attri, L.K.; Nayyar, H.; Bhanwra, R.K.; Pehwal, A. Pollination-induced oxidative stress in floral organs of Cymbidium pendulum (Roxb.) Sw. and Cymbidium aloifolium (L.) Sw. (Orchidaceae): A biochemical investigation. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 116, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Z.; Mandal, A.K.A.; Datta, S.K.; Biswas, A.K. Decline in ascorbate peroxidase activity—A prerequisite factor for tepal senescence in gladiolus. J. Plant Physiol. 2006, 163, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Reactive species and antioxidants. Redox biology is a fundamental theme of aerobic life. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.J. Is there an important role for reactive oxygen species and redox regulation during floral senescence? Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, D.; Chatterjee, J.; Datta, S.K. Oxidative stress and antioxidant activity as the basis of senescence in chrysanthemum florets. Plant Growth Regul. 2007, 53, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Shan, N.; Ma, N.; Bai, J.; Gao, J. Regulation of ascorbate peroxidase at the transcript level is involved in tolerance to postharvest water deficit stress in the cut rose (Rosa hybrida L.) cv. Samantha. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2006, 40, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Takatsu, Y.; Kasumi, M.; Ichimura, K.; van Doorn, W.G. Nuclear fragmentation and DNA degradation during programmed cell death in petals of morning glory (Ipomoea nil). Planta 2006, 224, 1279–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, T.; Takatsu, Y.; Kasumi, M.; Manabe, T.; Hayashi, M.; Marubashi, W.; Niwa, M. Novel evaluation method of flower senescence in freesia (Freesia hybrida) based on apoptosis as an indicator. Plant Biotechnol. 2001, 18, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Takatsu, Y.; Manabe, T.; Kasumi, M.; Marubashi, W. Suppressive effect of trehalose on apoptotic cell death leading to petal senescence in ethylene-insensitive flowers of gladiolus. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kington, S. The international daffodil register and classified list 2008. Royal Horticultural Society: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N. A photometric adaptation of the Somogyi method for the determination of glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 1944, 153, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jędrzejuk, A.; Rabiza-Świder, J.; Skutnik, E.; Łukaszewska, A. Some factors affecting longevity of cut lilacs. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2016, 111, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta 1991, 196, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galbraith, D.W.; Harkins, K.R.; Maddox, J.M.; Ayres, N.M.; Sharma, D.P.; Firoozabady, E. Rapid flow cytometric analysis of the cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 1983, 220, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójcik, A.R.; Laudański, Z. Statistical Planning and Concluding in Experimental Works; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1989; p. 130. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

| Content/Activity | Part of the Flower | Term (Date) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Harvest Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| total sugars [mg·g−1DW] | perianth | B 485.4 c | A 413.0 b | A 422.9 b | A 404.2 b | A 328.9 a | B 460.0 c | B 566.3 d |

| corona | A 436.2 a | B 484.6 b | B 567.9 c | B 647.3 d | B 546.0 c | A 412.5 a | A 382.3 a | |

| reducing sugars [mg·g−1DW] | perianth | A 150.2 a | A 269.5 b | A 317.1 e | A 296.6 de | A 256.5 b | A 306.8 e | A 279.0 bc |

| corona | A 132.8 a | B 300.0 c | A 307.1 c | A 293.9 c | A 230.0 b | A 284.4 c | A 268.3 bc | |

| free proline [µmol·g−1DW] | perianth | A 1.93 a | A 2.74 b | A 3.97 c | A 4.83 d | A 4.24 cd | B 7.69 e | A 11.36 f |

| corona | A 1.89 a | A 2.85 b | A 4.11 c | B 5.49 d | B 5.13 e | A 6.80 f | A 11.12 g | |

| malondialdehyde MDA [nmol·g−1DW] | perianth | B 121.0 a | B 127.9 b | B 139.4 cd | A 133.0 bc | A 108.3 a | B 147.8 d | A 137.9 c |

| corona | A 109.8 a | A 101.0 a | A 126.6 c | B 147.0 e | A 114.2 b | A 139.8 de | A 136.4 d | |

| hydrogen peroxide [μg·g−1DW] | perianth | A 1.63 ab | B 1.73 bc | B 1.42 a | B 1.54 ab | B 1.64 ab | B 1.91 c | B 2.22 d |

| corona | A 1.58 d | A 0.85 a | A 1.14 bc | A 0.97 ab | A 0.74 a | A 1.32 c | A 0.85 a | |

| catalase [mcatal·g−1DW] | perianth | B 1143.1 a | A 1398.1 a | B 2764.2 b | A 1373.3 a | A 1312.3 a | A 3194.2 b | B 5319.1 c |

| corona | A 569.7 a | B 2817.6 c | A 1544.1 b | B 4338.7 e | B 4190.8 e | A 3480.5 d | A 4678.7 e | |

| Content/Activity | Part of the Flower | Term (Date) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  | ||

| Harvest Day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| total sugars [mg·g−1DW] | perianth | B 437.0 bc | B 466.8 d | A 322.6 a | B 415.4 bc | B 444.3 cd | A 399.9 b | B 339.1 a | B 345.3 a |

| corona | A 338.8 b | A 400.4 c | B 347.8 bc | A 281.3 b | A 342.1 bc | A 381.9 c | A 261.4 a | A 181.1 a | |

| reducing sugars [mg·g−1DW] | perianth | A 182.9 b | A 142.3 a | A 256.2 d | B 372.2 f | B 339.2 e | B 348.7 ef | B 234.6 cd | B 215.5 c |

| corona | A 186.9 de | A 120.6 a | A 239.2 f | A 197.5 e | A 178.9 de | A 171.9 cd | A 152.5 bc | A 137.7 ab | |

| free proline [µmol·g−1DW] | perianth | B 3.15 b | A 2.51 a | A 2.60 a | B 5.52 c | B 8.64 e | B 7.47 d | B 9.29 f | A 9.81 f |

| corona | A 2.46 a | A 1.99 a | B 3.19 b | A 4.61 c | A 6.35 d | A 6.21 d | A 8.10 e | B 11.13 f | |

| malondialdehyde MDA [nmol·g−1DW] | perianth | B 142.0 b | B 147.9 b | B 159.4 cd | A 153.0 bc | A 128.3 a | B 167.8 d | A 159.9 cd | B 175.2 d |

| corona | A 129.5 a | A 121.0 a | A 146.3 c | B 168.1 e | A 134.1 b | A 159.9 de | A 154.4 d | A 160.2 d | |

| hydrogen peroxide [μg·g−1DW] | perianth | B 2.66 b | B 2.03 a | A 2.05 a | B 2.12 a | A 1.95 a | B 2.36 ab | B 1.97 a | B 2.68 b |

| corona | A 2.24 c | A 1.61 ab | A 2.19 c | A 1.57 ab | A 1.72 b | A 2.04 c | A 1.35 a | A 1.72 b | |

| catalase [mcatal·g−1DW] | perianth | A 1073.1 bc | A 751.7 a | A 894.4 ab | A 1109.4 c | A 979.5 bc | A 1081.8 bc | A 1337.9 d | A 2786.7 e |

| corona | B 1693.0 b | A 716.7 a | B 2974.7 d | B 1799.6 b | B 2069.6 bc | B 1797.8 b | B 2128.4 bc | A 2383.9 c | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rabiza-Świder, J.; Sutrisno; Salachna, P.; Zawadzińska, A.; Skutnik, E. The Senescence of Cut Daffodil Flowers Correlates with Programmed Cell Death Symptoms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157657

Rabiza-Świder J, Sutrisno, Salachna P, Zawadzińska A, Skutnik E. The Senescence of Cut Daffodil Flowers Correlates with Programmed Cell Death Symptoms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(15):7657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157657

Chicago/Turabian StyleRabiza-Świder, Julita, Sutrisno, Piotr Salachna, Agnieszka Zawadzińska, and Ewa Skutnik. 2025. "The Senescence of Cut Daffodil Flowers Correlates with Programmed Cell Death Symptoms" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 15: 7657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157657

APA StyleRabiza-Świder, J., Sutrisno, Salachna, P., Zawadzińska, A., & Skutnik, E. (2025). The Senescence of Cut Daffodil Flowers Correlates with Programmed Cell Death Symptoms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(15), 7657. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157657