Immunological Markers Associated with Skin Manifestations of EGPA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

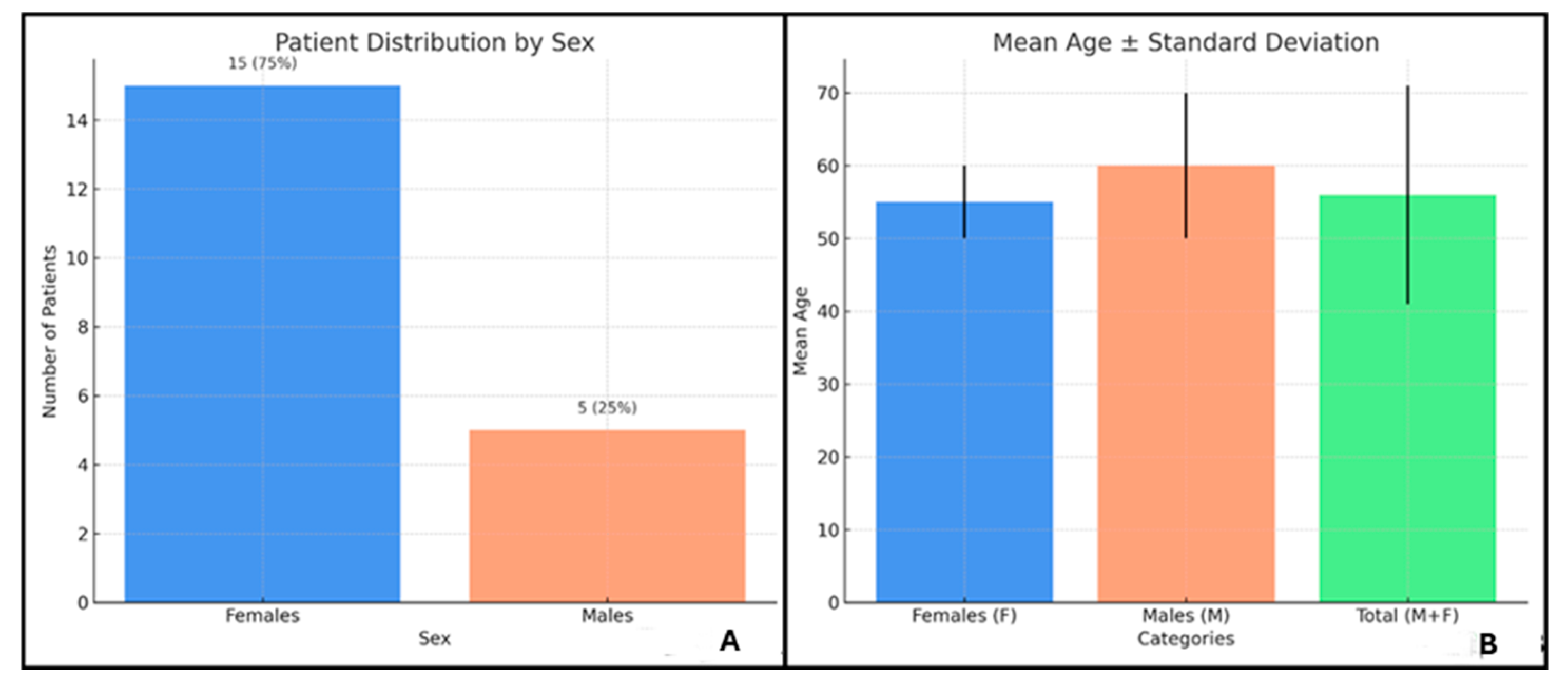

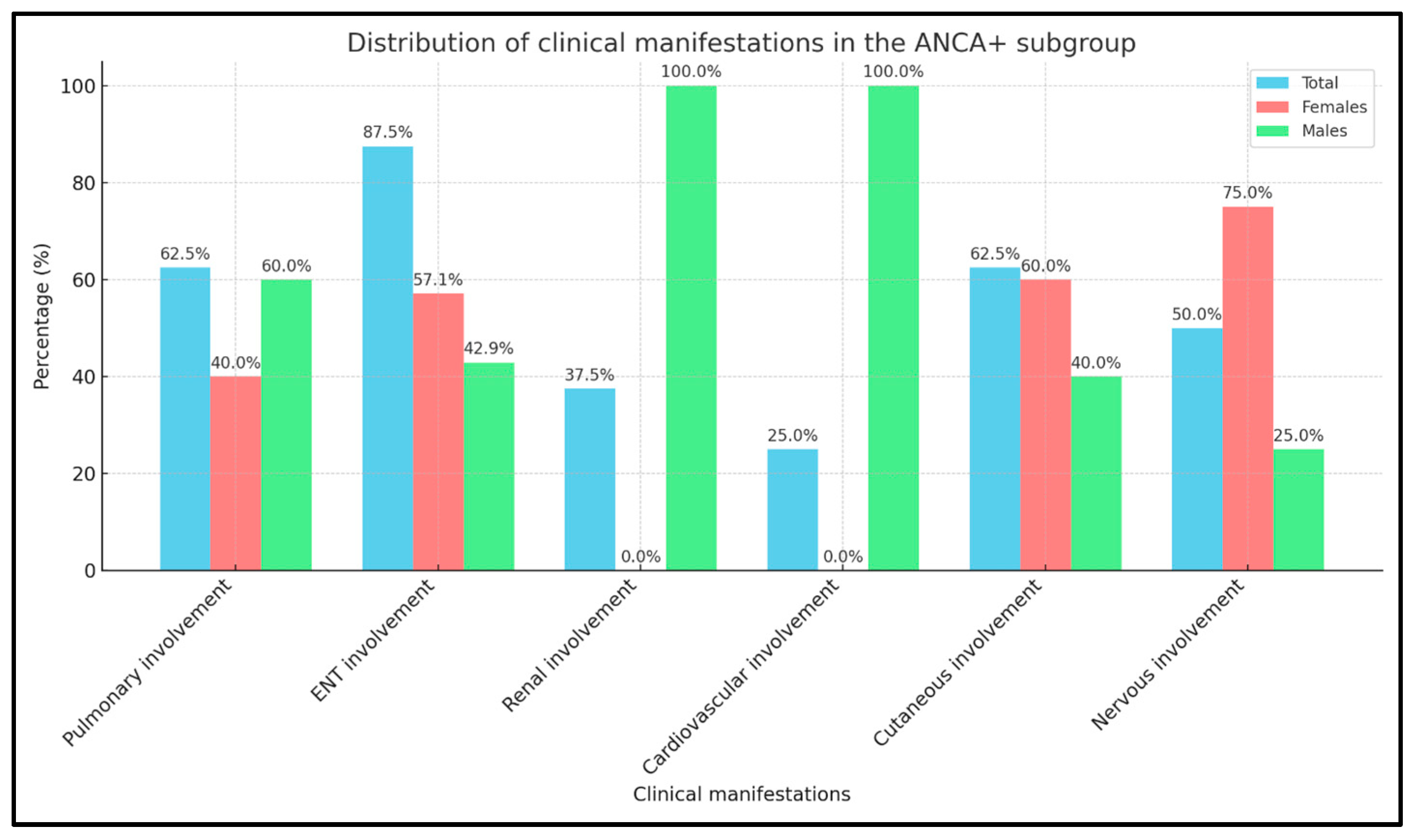

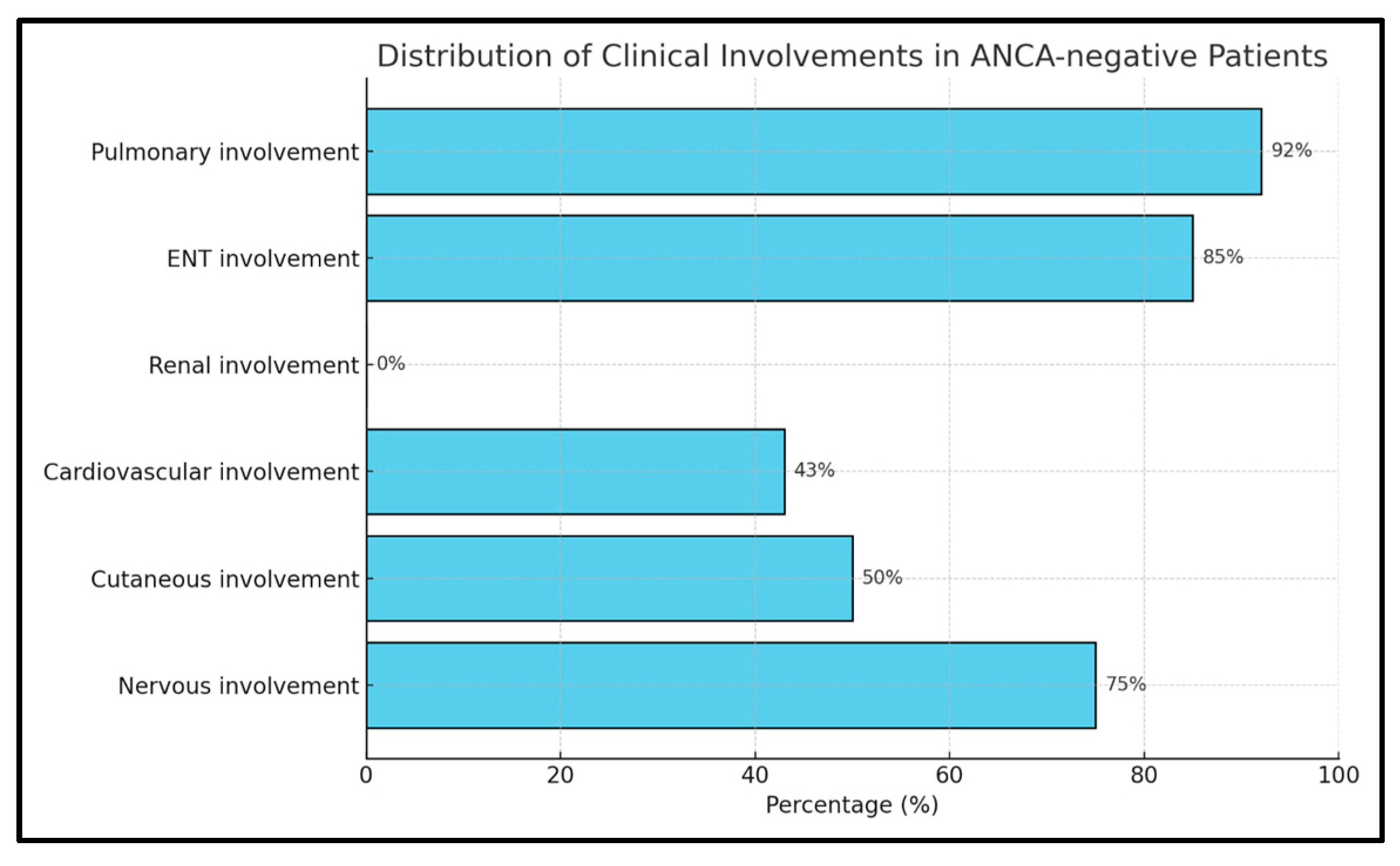

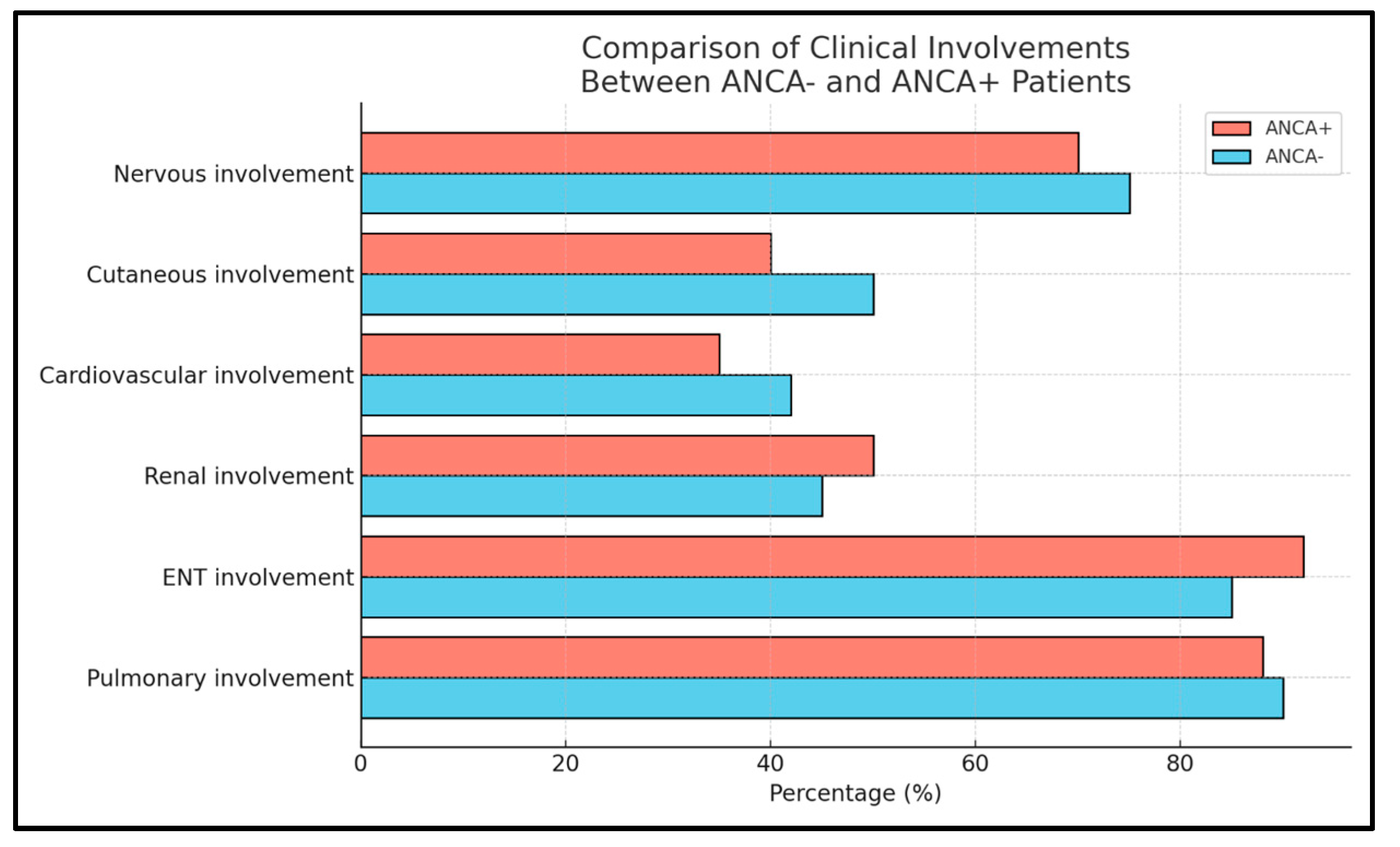

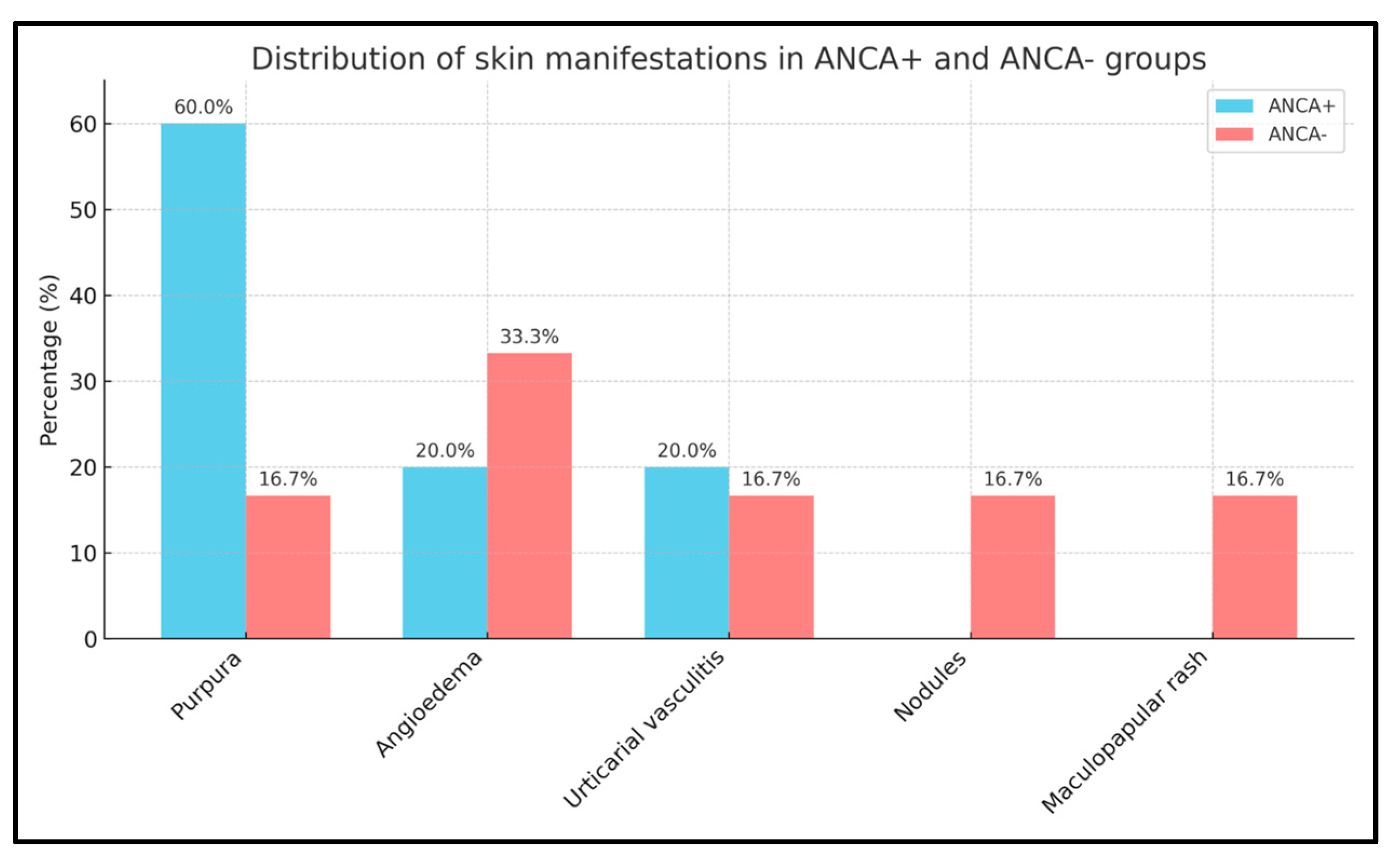

2.1. Distribution of Clinical Features in ANCA+ and ANCA− EGPA Patients

2.2. ANA Titration in ANCA+ and ANCA− EGPA Patients

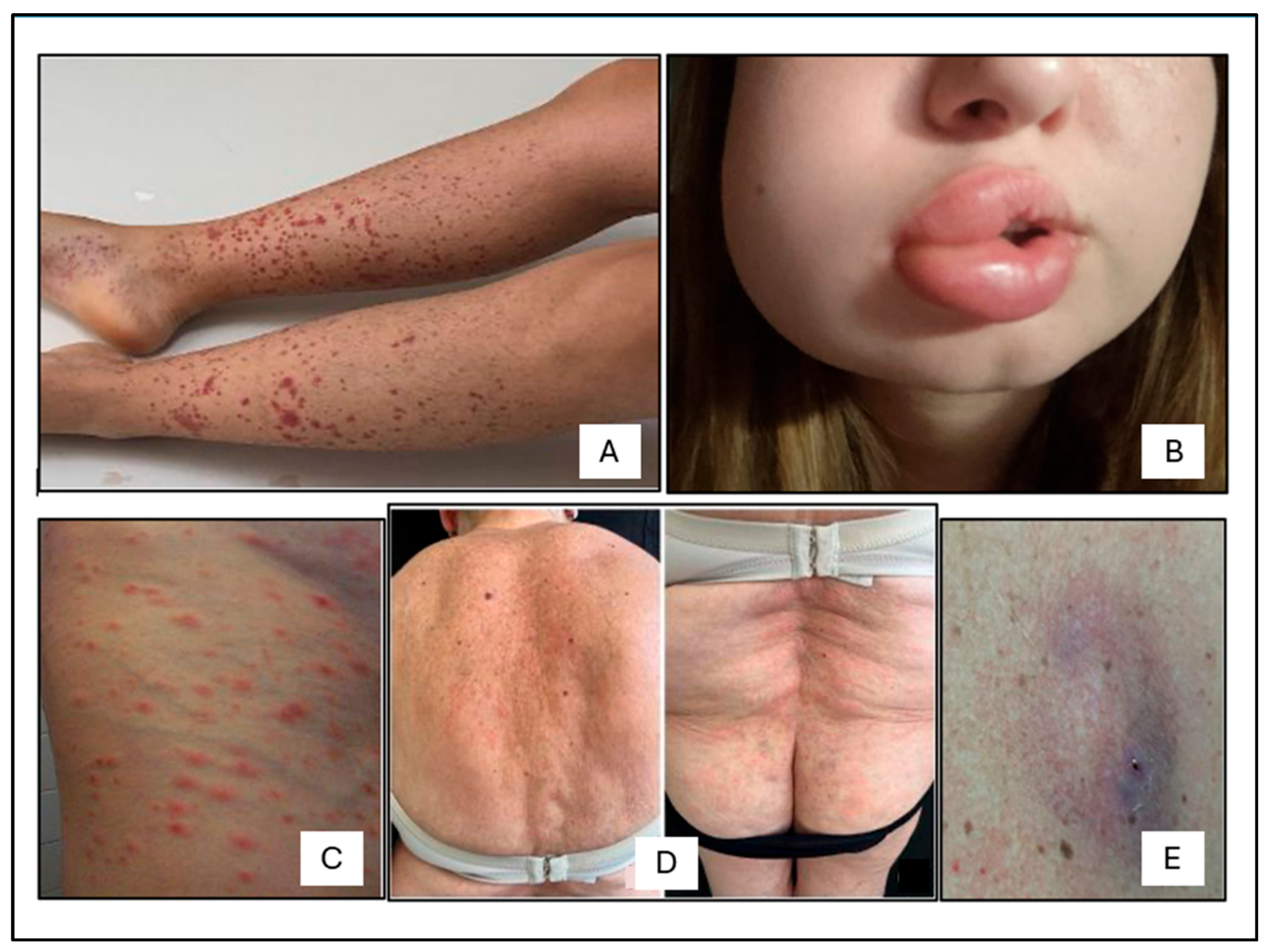

2.3. Cutaneous Manifestations

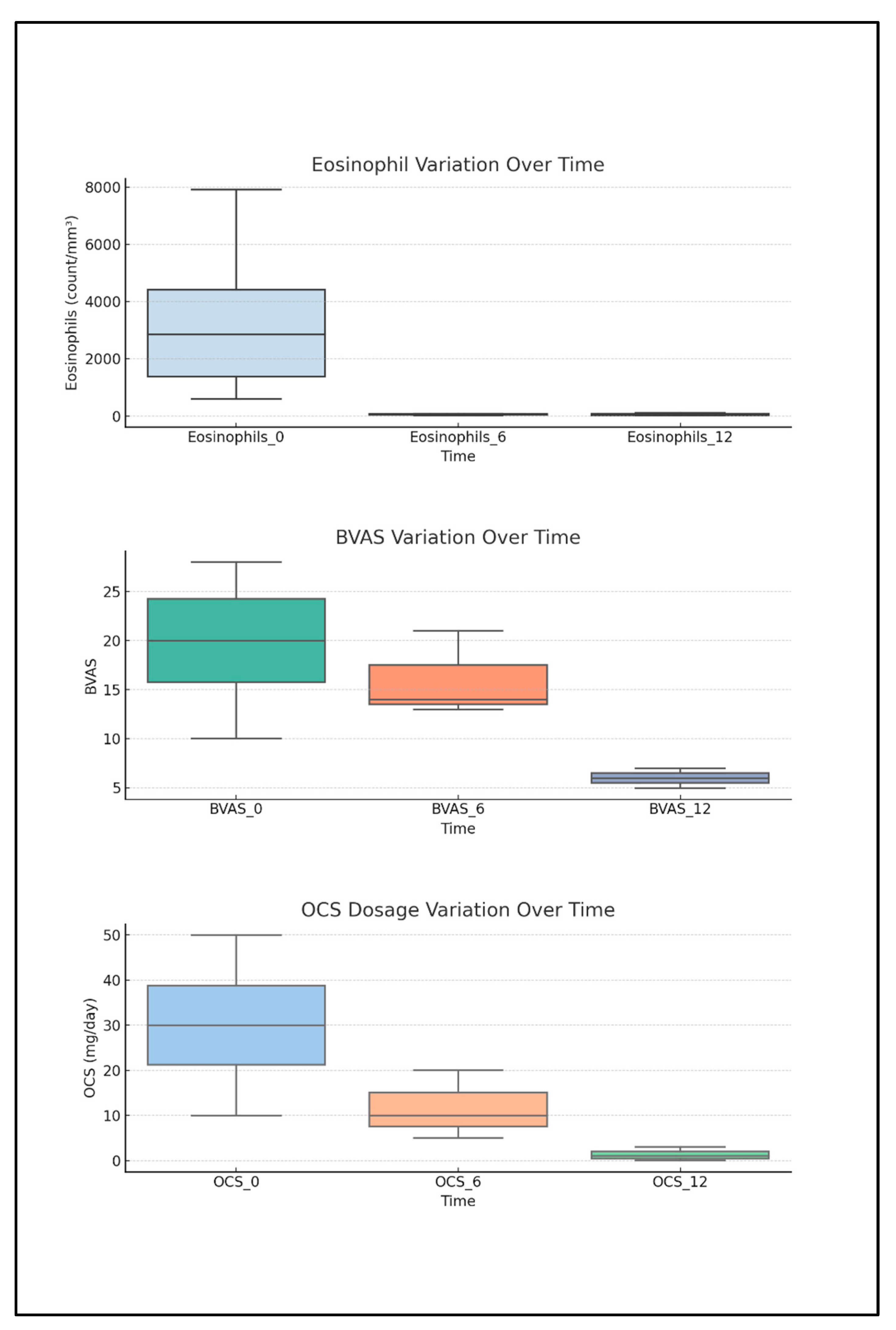

2.4. Descriptive Analysis of Biomarkers, BVASs, and OCS Intake Correlated to Anti-IL5 Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGPA | Eosinophilic granulomatosis with eosinophilia |

| PTS | Patients |

| F | Females |

| M | Males |

| ANCA | Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody |

| ANA | Antinuclear antibodies |

| BVAS | Birmingham vasculitis activity score |

References

- Churg, J.; Strauss, L. Allergic granulomatosis; allergic angiitis, periarteritis nodosa. Am. J. Pathol. 1951, 27, 277–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- White, J.; Dubey, S. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakes, R.W.; Kwon, N.; Nordstrom, B.; Goulding, R.; Fahrbach, K.; Tarpey, J.; Van Dyke, M.K. Burden of illness associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 4829–4836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatroni, M.; Oliva, E.; Gianfreda, D.; Gregorini, G.; Allinovi, M.; Ramirez, G.A.; Bozzolo, E.P.; Monti, S.; Bracaglia, C.; Marucci, G.; et al. ANCA-associated vasculitis in childhood: Recent advances. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walulik, A.; Łysak, K.; Błaszkiewicz, M.; Górecki, I.; Gomułka, K. The Role of Neutrophils in ANCA-Associated Vasculitis: The Pathogenic Role and Diagnostic Utility of Autoantibodies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagni, F.; Bello, F.; Emmi, G. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Dissecting the Pathophysiology. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 627776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijolek, J.; Radzikowska, E. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis—Advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1145257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.-C.; Chou, P.-C.; Lai, C.-Y.; Tsai, H.-H. Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies and Organ-Specific Manifestations in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2021, 9, 445–452.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Han, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Tian, X.; Zeng, X.; Wang, L.; Zhang, F. Clinical Significance of MPO-ANCA in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Experience From a Longitudinal Chinese Cohort. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 885198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskari, K.; Hellmich, B.; Adamus, G.; Csernok, E. Autoantibody profile in eosinophilic granulomatosis and polyangiitis: Predominance of anti-alpha-enolase antibodies. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comarmond, C.; Pagnoux, C.; Khellaf, M.; Cordier, J.; Hamidou, M.; Viallard, J.; Maurier, F.; Jouneau, S.; Bienvenu, B.; Puéchal, X.; et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): Clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013, 65, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinico, R.A.; Di Toma, L.; Maggiore, U.; Bottero, P.; Radice, A.; Tosoni, C.; Grasselli, C.; Pavone, L.; Gregorini, G.; Monti, S.; et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 2926–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, B.; Bibby, S.; Steele, R.; Weatherall, M.; Nelson, H.; Beasley, R. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies and myeloperoxidase autoantibodies in clinical expression of Churg-Strauss syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 131, 571–576.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdziarski, P.; Ricciardi, L.; Paganelli, R. Editorial: Case reports in respiratory pharmacology 2022. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1242273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solans-Laqué, R.; Fraile, G.; Rodriguez-Carballeira, M.; Caminal, L.; Castillo, M.J.; Martínez-Valle, F.; Sáez, L.; Rios, J.J.; Solanich, X.; Oristrell, J.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of Spanish patients with ANCA-associated vasculitides. Medicine 2017, 96, e6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, H.; Tomita, T.; Kondo, M.; Mukai, M. Presence of purpura is related to active inflammation in association with IL-5 in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durel, C.; Berthiller, J.; Caboni, S.; Jayne, D.; Ninet, J.; Hot, A. Long-Term Followup of a Multicenter Cohort of 101 Patients With Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss). Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, L.; Soler, D.G.; Bennici, A.; Brunetto, S.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Case Report: Severe Eosinophilic Asthma Associated With ANCA-Negative EGPA in a Young Adult Successfully Treated With Benralizumab. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 858344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micheletti, R.G.; Fuxench, Z.C.; Craven, A.; Watts, R.A.; Luqmani, R.A.; Merkel, P.A. Cutaneous Manifestations of Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody–Associated Vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumholtz, L.; Laurent-Roussel, S.; Aumaître, O.; Maurier, F.; Le Guenno, G.; Carlotti, A.; Dallot, A.; Kemeny, J.L.; Antunes, L.; Froment, N.; et al. Clinical and pathological significance of cutaneous manifestations in ANCA-associated vasculitides. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakshouk, H.; Gibson, L.E. Cutaneous manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis: A retrospective review of 211 cases with emphasis on clinicopathologic correlation and ANCA status. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmi, G.; Bettiol, A.; Gelain, E.; Bajema, I.M.; Berti, A.; Burns, S.; Cid, M.C.; Tervaert, J.W.C.; Cottin, V.; Durante, E.; et al. Evidence-Based Guideline for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 19, 378–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, D.G.; Bennici, A.; Brunetto, S.; Gangemi, S.; Ricciardi, L. Benralizumab in the management of rare primary eosinophilic lung diseases. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2022, 43, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, R.; Hashimoto, M. Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis: Latest Findings and Updated Treatment Recommendations. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvino, P.; Quartuccio, L.; Robson, J.C.; Ferretti, V.V.; Klersy, C.; Alberici, F.; Bagnasco, D.; Berti, A.; Caminati, M.; Camoni, M.; et al. Impact of mepolizumab on the AAV-PRO questionnaire in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: Data from a European multicentre study. Rheumatology 2025, keaf232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlBloushi, S.; Al-Ahmad, M. Exploring the immunopathology of type 2 inflammatory airway diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1285598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sablé-Fourtassou, R.; Cohen, P.; Mahr, A.; Pagnoux, C.; Mouthon, L.; Jayne, D.; Blockmans, D.; Cordier, J.-F.; Delaval, P.; Puechal, X.; et al. Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibodies and the Churg–Strauss Syndrome. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldini, C.; Talarico, R.; Della Rossa, A.; Bombardieri, S. Clinical Manifestations and Treatment of Churg-Strauss Syndrome. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 36, 527–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, P.C.; Ponte, C.; Suppiah, R.; Robson, J.C.; Craven, A.; Judge, A.; Khalid, S.; Hutchings, A.; Luqmani, R.A.; Watts, R.A.; et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022, 74, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prendecki, M.; Gurung, A.; Pisacano, N.; Pusey, C.D. The role of neutrophils in ANCA-associated vasculitis. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 270, 106933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matucci, A.; Vivarelli, E.; Perlato, M.; Mecheri, V.; Accinno, M.; Cosmi, L.; Parronchi, P.; Rossi, O.; Vultaggio, A. EGPA Phenotyping: Not Only ANCA, but Also Eosinophils. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmark, T.; Ohlsson, S.; Pettersson, Å.; Hansson, M.; Johansson, Å.C.M. Eosinophils in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis. BMC Rheumatol. 2019, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.W.; Ahn, S.S.; Song, J.J.; Park, Y.-B.; Lee, S.-W. Clinical implications of peripheral eosinophil count at diagnosis in patients newly diagnosed with microscopic polyangiitis and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2023, 25, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoury, P.; Grayson, P.C.; Klion, A.D. Eosinophils in vasculitis: Characteristics and roles in pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.C.; Fernandes, E.L.; Miquelin, G.M.; Colferai, M.M.T. Cutaneous manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: Key to diagnosis. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2017, 92 (Suppl. S1), 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caro-Chang, L.A.; Fung, M.A. The role of eosinophils in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory skin diseases. Hum. Pathol. 2023, 140, 101–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.; Kitching, A.R.; Witko-Sarsat, V.; Wiech, T.; Specks, U.; Klapa, S.; Comdühr, S.; Stähle, A.; Müller, A.; Lamprecht, P. Myeloperoxidase-specific antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Lancet Rheumatol. 2024, 6, e300–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullo, A.L.; Kitching, A.R.; Witko-Sarsat, V.; Wiech, T.; Specks, U.; Klapa, S.; Comdühr, S.; Stähle, A.; Müller, A.; Lamprecht, P. Arterial Stiffness and Adult Onset Vasculitis: A Systematic Review. Front. Med. 2022, 9, e300–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraticelli, P.; Benfaremo, D.; Gabrielli, A. Diagnosis and management of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 16, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aymonnier, K.; Amsler, J.; Lamprecht, P.; Salama, A.; Witko-Sarsat, V. The neutrophil: A key resourceful agent in immune-mediated vasculitis. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 314, 326–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabb, E.S.; Duncan, L.M.; Nazarian, R.M. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: Cutaneous clinical and histopathologic differential diagnosis. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2021, 48, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, L.; Falcinelli, F.; Lamberti, A.; Cinotti, E.; Rubegni, P. Erythema annulare centrifugum as clinical manifestation of-eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 159, 454–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Chen, K.-R. A Complex Vasculitis: Thrombophlebitis, Subcutaneous Granulomatous Arteritis, and Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis Presenting Clinically as Livedo Racemosa With Nodular Erythema. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2024, 46, 634–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frątczak, A.; Polak, K.; Miziołek, B.; Bergler-Czop, B. Torasemide-induced Vascular Purpura in the Course of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Acta Dermatovenerol. Croat. 2022, 30, 116–118. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, C.; Shenk, M.E.R.; Martin, K.; Launhardt, A. Cutaneous manifestations of childhood Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (cEGPA): A case-based review. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2020, 37, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiiyama, R.; Chen, K.-R.; Ishibashi, M. A Case of Cutaneous Arteritis Presenting as Infiltrated Erythema in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Features of the Unique Morphological Evolution of Arteritis as a Diagnostic Clue. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2019, 41, 832–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, C. Distribution Characteristics of ANA and ANCA in Patients with Hyperthyroidism. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets. 2021, 21, 1993–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sánchez, C.; Benavides-Solarte, M.; Galindo-Ibáñez, I.; Ospina-Caicedo, A.I.; Parra-Izquierdo, V.; Chila-Moreno, L.; Villa, A.; Casas-Gómez, M.C.; Angarita, I.; Bautista-Molano, W.; et al. Frequency of Positive ANCA Test in a Population With Clinical Symptoms Suggestive of Autoimmune Disease and the Interference of ANA in its Interpretation. Reumatol. Clin. 2020, 16, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, P.C.; Ponte, C.; Suppiah, R.; Robson, J.C.; Craven, A.; Judge, A.; Khalid, S.; Hutchings, A.; A Luqmani, R.; A Watts, R.; et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology Classification Criteria for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2022, 81, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtyar, C.; Lee, R.; Brown, D.; Carruthers, D.; Dasgupta, B.; Dubey, S.; Flossmann, O.; Hall, C.; Hollywood, J.; Jayne, D.; et al. Modification and validation of the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (version 3). Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Total pts (n = 20) | ANCA− pts (n = 12) | ANCA+ pts (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANA positive (n, %) | 10 (50%) | 8 (66.7%) | 2 (25%) |

| ANA negative (n, %) | 10 (50%) | 4 (33.3%) | 6 (75%) |

| N. | Authors and Year of Publication | Type of Study | DOI | Title | Aims | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laura Calabrese et al., 2024 [42] | Case report | DOI: https://doi.org/10.23736/S2784-8671.24.07713-2. | Erythema annulare centrifugum as clinical manifestation of -eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis—PubMed | A rare case of superficial erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC), occurring in a patient with EGPA is reported highlighting the importance of recognizing figured erythemas as potential cutaneous manifestations of EGPA to improve diagnosis and management. | This case expands the known skin manifestations of EGPA by reporting superficial erythema annulare centrifugum. Recognizing figured erythemas in EGPA is important for accurate diagnosis and treatment. Further studies are needed to clarify their role and frequency. |

| 2 | Yamamoto Toshiyuki et al., 2024 [43] | Letter to the Editor | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0000000000002763 | A Complex Vasculitis: Thrombophlebitis, Subcutaneous Granulomatous Arteritis, and Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis Presenting Clinically as Livedo Racemosa With Nodular Erythema—PubMed | It describes a rare case of EGPA characterized by the coexistence of dermo-subcutaneous junctional thrombophlebitis and deep subcutaneous granulomatous arteritis within the same biopsy specimen, and highlights the diagnostic value of excisional biopsy in EGPA patients presenting with livedo racemosa and nodular erythema. | This case underscores the critical role of deep excisional biopsy in EGPA patients presenting with livedo racemosa (reticularis), nodular erythema, or subcutaneous nodules, as it is essential for identifying the diagnostic hallmark of granulomatous arteritis. |

| 3 | Aleksandra Fratczak et al., 2022 [44] | Case report | DOI not available | Torasemide-induced Vascular Purpura in the Course of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis—PubMed | A case of EGPA with cutaneous vasculitis potentially triggered by torasemide is described, emphasizing the role of drug exposure in disease onset. | This is the first case report on torasemide-induced vascular purpura in the context of EGPA. The temporal association between torasemide initiation and symptoms’ onset suggests the drug may act as an aggravating factor in latent EGPA. Careful evaluation of recent drug exposure is crucial in all cases of new-onset vasculitis to improve diagnosis and outcomes. |

| 4 | Catherine Bridges et al., 2020 [45] | Review | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14144 | Cutaneous manifestations of childhood (cEGPA): A case-based review—PubMed | Clinical and histopathological characteristics of skin involvement in pediatric EGPA is described. | The high prevalence of skin involvement in cEGPA highlights the importance of dermatologic expertise in the early detection for a prompt recognition, despite diagnostic complexity, to optimize therapeutic success in affected children. |

| 5 | Rie Shiiyama et al., 2019 [46] | Case report | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0000000000001451 | A Case of Cutaneous Arteritis Presenting as Infiltrated Erythema in Eosinophilic Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: Features of the Unique Morphological Evolution of Arteritis as a Diagnostic Clue—PubMed | A rare case of EGPA with cutaneous lesions involving different stages of subcutaneous muscular vessel vasculitis is presented, highlighting the diagnostic significance of eosinophilic and granulomatous arteritis in the same artery. | This case shows that the coexistence of eosinophilic and granulomatous arteritis within a single subcutaneous muscular artery can serve as a unique and valuable histopathological clue for diagnosing EGPA, especially in the context of cutaneous involvement. |

| 6 | Camila Carneiro Marques et al., 2017 [35] | Case report | DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175522 | Cutaneous manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: key to diagnosis—PubMed | A case of a female patient affected by EGPA with important systemic manifestations and not very florid skin lesions is described. | Recognition of skin lesions by the dermatologist was essential for the clinical suspicion and confirmation of diagnosis, which allowed adequate treatment, reducing morbidity and contributing to prevent irreversible lesions in vital organs. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brunetto, S.; Buta, F.; Gangemi, S.; Ricciardi, L. Immunological Markers Associated with Skin Manifestations of EGPA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157472

Brunetto S, Buta F, Gangemi S, Ricciardi L. Immunological Markers Associated with Skin Manifestations of EGPA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(15):7472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157472

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrunetto, Silvia, Federica Buta, Sebastiano Gangemi, and Luisa Ricciardi. 2025. "Immunological Markers Associated with Skin Manifestations of EGPA" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 15: 7472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157472

APA StyleBrunetto, S., Buta, F., Gangemi, S., & Ricciardi, L. (2025). Immunological Markers Associated with Skin Manifestations of EGPA. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(15), 7472. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26157472