Reduced Glycolysis and Cytotoxicity in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis as Strategies for Host Adaptation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Control Subjects’ and CRS Patients’ Characteristics

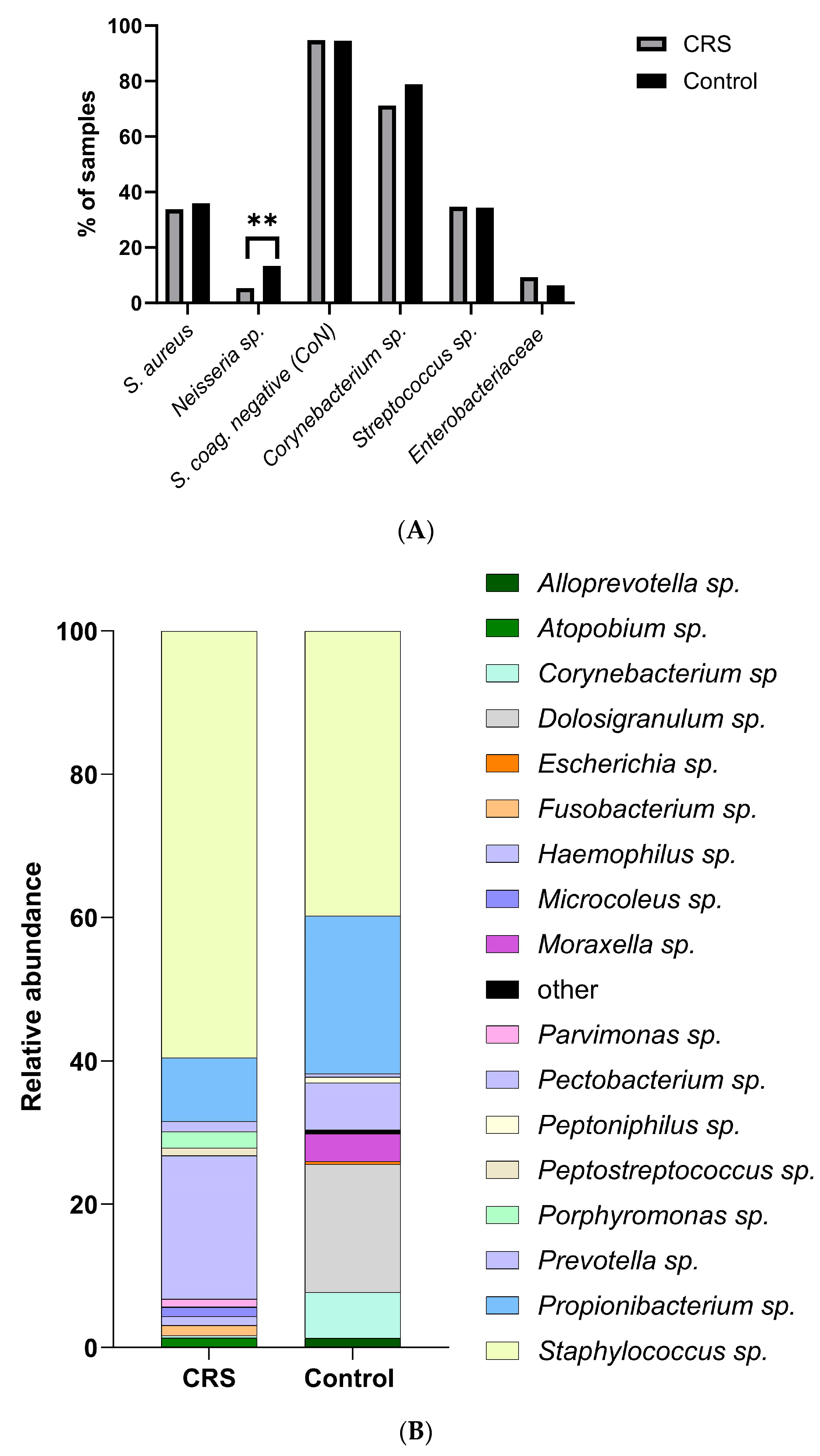

2.2. CRS and Control Donors Had Similar Nasal Microbiomes

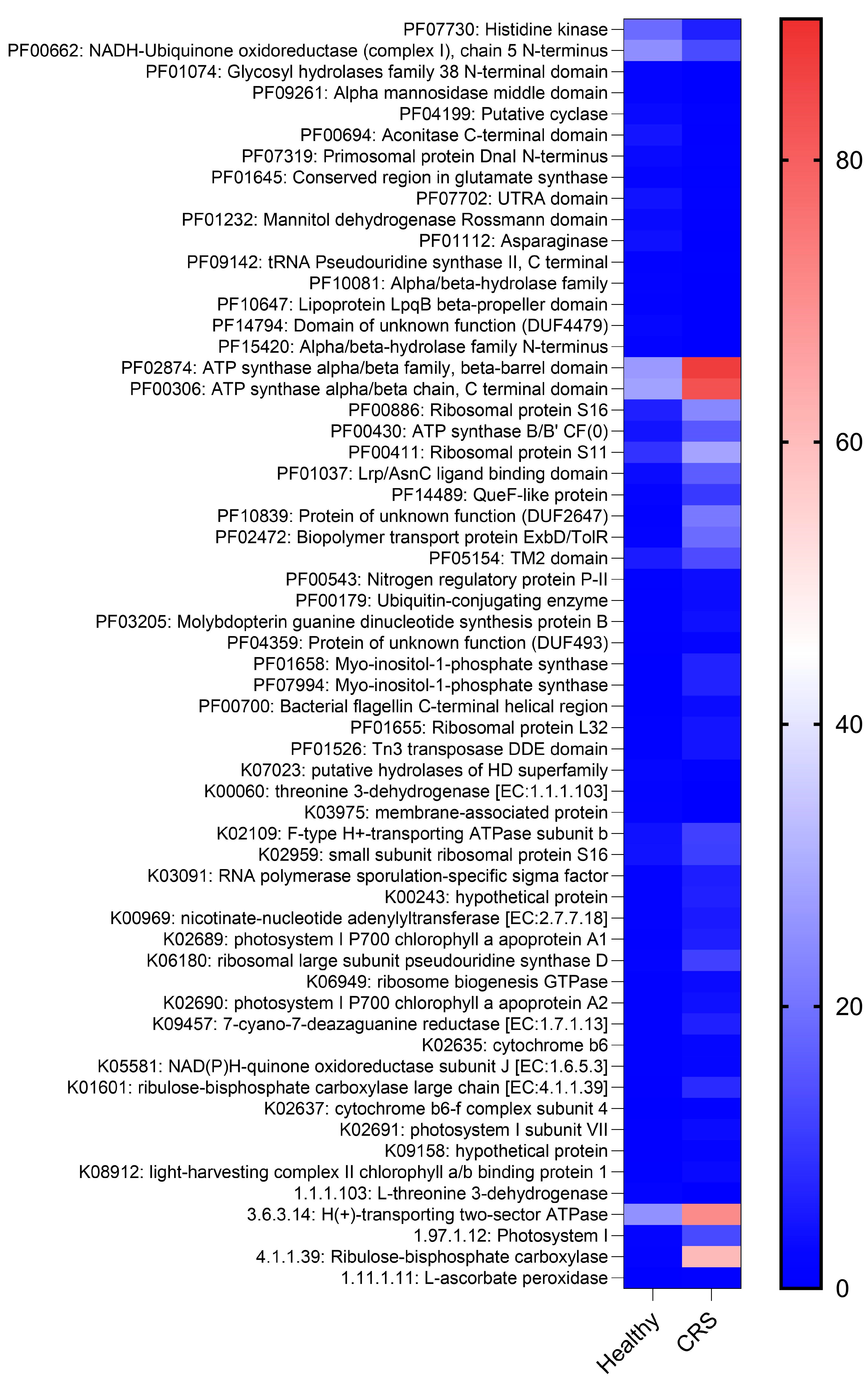

2.3. CRS and Control Microenvironments Were Distinguished by Metabolic Pathways

2.4. S. aureus Populations of Patients and Controls Did Not Differ

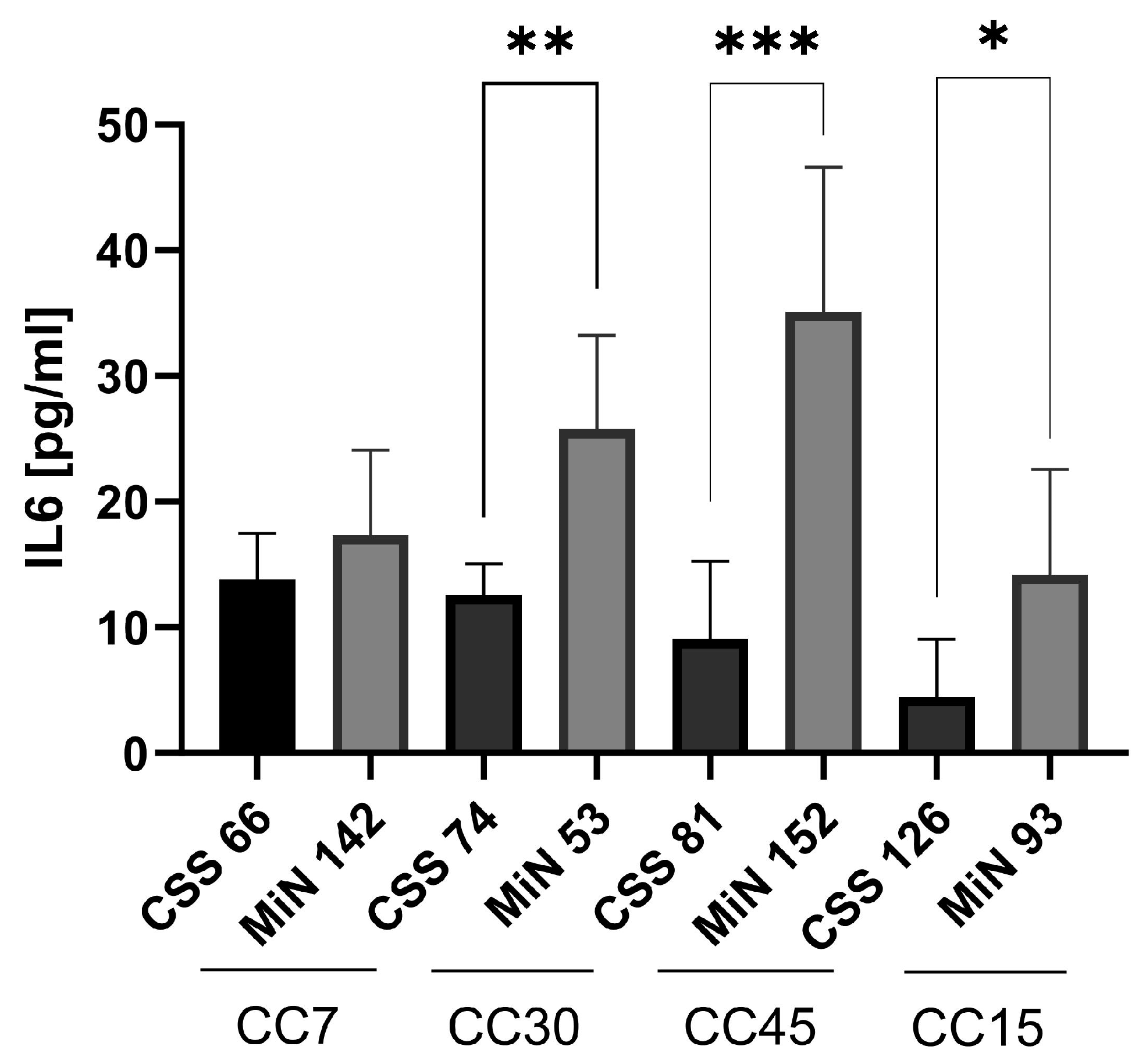

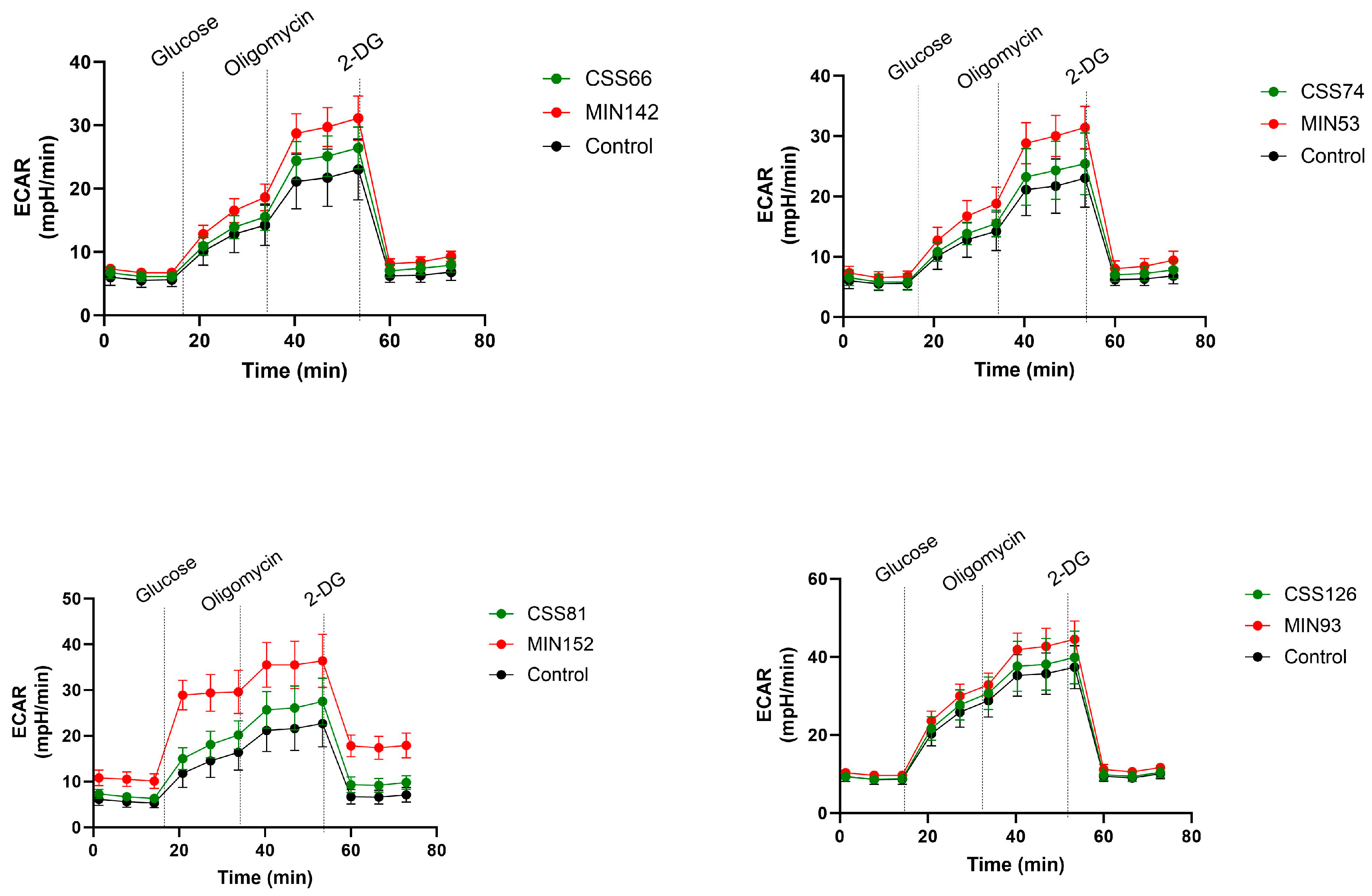

2.5. S. aureus Isolated from CRS Donors Induced Less Cytotoxicity and Glycolysis in Host Cells than Control Strains

2.6. Cyotoxicity Induced on Host Cells by Control Strains Changed with Serial Passages

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Patient Enrollment

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. Metagenomic Sequencing:

4.4. Metagenomics Analysis/Data Processing

4.5. Cells

4.6. Cell Death Induction

4.7. Measurement of IL-6 by ELISA

4.8. CAMP Test: Assessment of Agr Activity on Sheep Blood Agar Plates

4.9. Extracellular Flux Analysis

4.10. Serial Bacterial Cultivation

4.11. Microarray-Based Characterisation of S. aureus Isolates

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dietz de Loos, D.; Lourijsen, E.S.; Wildeman, M.A.M.; Freling, N.J.M.; Wolvers, M.D.J.; Reitsma, S.; Fokkens, W.J. Prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis in the general population based on sinus radiology and symptomatology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellings, P.W. SWOT Analysis of Chronic Rhinosinusitis Care Anno 2022. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1468–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C.; Pawankar, R.; Zhang, L.; Bunnag, C.; Fokkens, W.J.; Hamilos, D.L.; Jirapongsananuruk, O.; Kern, R.; Meltzer, E.O.; Mullol, J.; et al. ICON: Chronic rhinosinusitis. World Allergy Organ. J. 2014, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.Y.; Tan, B.K. Risk factors for chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedaghat, A.R.; Kuan, E.C.; Scadding, G.K. Epidemiology of Chronic Rhinosinusitis: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2022, 10, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachert, C.; Marple, B.; Schlosser, R.J.; Hopkins, C.; Schleimer, R.P.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Bröker, B.M.; Laidlaw, T.; Song, W.J. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okano, M.; Fujiwara, T.; Kariya, S.; Higaki, T.; Haruna, T.; Matsushita, O.; Noda, Y.; Makihara, S.; Kanai, K.; Noyama, Y.; et al. Cellular responses to Staphylococcus aureus alpha-toxin in chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Allergol. Int. 2014, 63, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna, T.; Kariya, S.; Fujiwara, T.; Higaki, T.; Makihara, S.; Kanai, K.; Fujiwara, R.; Iwasaki, S.; Noguchi, Y.; Nishizaki, K.; et al. Association between impaired IL-10 production following exposure to Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin B and disease severity in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergol. Int. 2018, 67, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.W.; Kim, D.Y.; Choi, S.; Won, S.; Kang, H.R.; Yi, H. Microbiome profiling of uncinate tissue and nasal polyps in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis using swab and tissue biopsy. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psaltis, A.J.; Mackenzie, B.W.; Cope, E.K.; Ramakrishnan, V.R. Unraveling the role of the microbiome in chronic rhinosinusitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 149, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivan, S.; Bassiouni, A.; Shiffer, A.; Dillon, M.R.; Cope, E.K.; Cooksley, C.; Ramezanpour, M.; Moraitis, S.; Ali, M.J.; Bleier, B.; et al. The international sinonasal microbiome study: A multicentre, multinational characterization of sinonasal bacterial ecology. Allergy 2020, 75, 2037–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Shariati, A.; Asghari, A.; Rajaeih, S.; Ghorbani, M.; Jalessi, M.; Mirshekar, M.; Razavi, S. Molecular analysis of dominant paranasal sinus bacteria in patients with and without chronic rhinosinusitis. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.F.; Leech, J.M.; Rogers, T.R.; McLoughlin, R.M. Staphylococcus aureus Colonization: Modulation of Host Immune Response and Impact on Human Vaccine Design. Front. Immunol. 2014, 4, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunberg, U.; Söderquist, B.; Hugosson, S. Bacterial findings in optimised sampling and characterisation of S. aureus in chronic rhinosinusitis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, V.R.; Feazel, L.M.; Abrass, L.J.; Frank, D.N. Prevalence and abundance of Staphylococcus aureus in the middle meatus of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, and asthma. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013, 3, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Eiff, C.; Becker, K.; Machka, K.; Stammer, H.; Peters, G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thunberg, U.; Hugosson, S.; Ehricht, R.; Monecke, S.; Müller, E.; Cao, Y.; Stegger, M.; Söderquist, B. Long-Term Sinonasal Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and Anti-Staphylococcal Humoral Immune Response in Patients with Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakr, A.; Brégeon, F.; Mège, J.L.; Rolain, J.M.; Blin, O. Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization: An Update on Mechanisms, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Subsequent Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.J.; Lee, J.H.; Won, H.K.; Bachert, C. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps in Older Adults: Clinical Presentation, Pathophysiology, and Comorbidity. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yan, J.; Wen, W.; Zhang, N.; Bachert, C. Pathophysiology and management of Staphylococcus aureus in nasal polyp disease. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2023, 19, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A.; Wong Fok Lung, T. Consequences of Metabolic Interactions during Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Toxins 2020, 12, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickersham, M.; Wachtel, S.; Wong Fok Lung, T.; Soong, G.; Jacquet, R.; Richardson, A.; Parker, D.; Prince, A. Metabolic Stress Drives Keratinocyte Defenses against Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 2742–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong Fok Lung, T.; Chan, L.C.; Prince, A.; Yeaman, M.R.; Archer, N.K.; Aman, M.J.; Proctor, R.A. Staphylococcus aureus adaptive evolution: Recent insights on how immune evasion, immunometabolic subversion and host genetics impact vaccine development. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1060810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.R.; Baron, E.J.; Jorgensen, J.H.; Landry, M.L.; Pfaller, M.A. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 9th ed.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Novick, R.P.; Geisinger, E. Quorum sensing in staphylococci. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2008, 42, 541–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traber, K.E.; Lee, E.; Benson, S.; Corrigan, R.; Cantera, M.; Shopsin, B.; Novick, R.P. Agr function in clinical Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Microbiol. (Read.) 2008, 154, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammal, A.; Tewfik, M.; Rousseau, S. Differences in RANTES and IL-6 levels among chronic rhinosinusitis patients with predominant gram-negative and gram-positive infection. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2017, 46, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cope, E.K.; Goldberg, A.N.; Pletcher, S.D.; Lynch, S.V. Compositionally and functionally distinct sinus microbiota in chronic rhinosinusitis patients have immunological and clinically divergent consequences. Microbiome 2017, 5, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederfuhr, A.; Kirsche, H.; Riechelmann, H.; Wellinghausen, N. The bacteriology of chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2009, 135, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, N.; Biswas, R.; Götz, F.; Biswas, L. Impact of Staphylococcus aureus on pathogenesis in polymicrobial infections. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 2162–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quince, C.; Walker, A.W.; Simpson, J.T.; Loman, N.J.; Segata, N. Shotgun metagenomics, from sampling to analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.S.; Willis, A.L.; Laubitz, D.; Sharma, S.; Song, B.H.; Chiu, A.G.; Le, C.H.; Chang, E.H. The effect of maxillary sinus antrostomy size on the sinus microbiome. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudien, M.; Gadola, S.D.; Podschun, R.; Hedderich, J.; Paulsen, J.; Reinhold-Keller, E.; Csernok, E.; Ambrosch, P.; Hellmich, B.; Moosig, F.; et al. Nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and endonasal activity in Wegener s granulomatosis as compared to rheumatoid arthritis and chronic Rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2010, 28, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaghayegh, G.; Cooksley, C.; Ramezanpour, M.; Wormald, P.J.; Psaltis, A.J.; Vreugde, S. Chronic Rhinosinusitis, S. aureus Biofilm and Secreted Products, Inflammatory Responses, and Disease Severity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, A.; Jervis-Bardy, J.; Boase, S.J.; Tan, L.; Wormald, P.J. Noninvasive Staphylococcus aureus biofilm determination in chronic rhinosinusitis by detecting the exopolysaccharide matrix component poly-N-acetylglucosamine. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013, 3, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howden, B.P.; Giulieri, S.G.; Wong Fok Lung, T.; Baines, S.L.; Sharkey, L.K.; Lee, J.Y.H.; Hachani, A.; Monk, I.R.; Stinear, T.P. Staphylococcus aureus host interactions and adaptation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, M. Critical Assessment of the Prospects of Quorum-Quenching Therapy for Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharara, S.L.; Maragakis, L.L.; Cosgrove, S.E. Decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 35, 107–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.W.; Yao, J.; Batte, J.L.; Gullett, J.M.; Subramanian, C.; Rosch, J.W.; Rock, C.O. Host Fatty Acid Utilization by Staphylococcus aureus at the Infection Site. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kengmo Tchoupa, A.; Peschel, A. Staphylococcus aureus Releases Proinflammatory Membrane Vesicles To Resist Antimicrobial Fatty Acids. mSphere 2020, 5, e00804–e00820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.; Hanzelmann, D.; Härtner, T.; Peschel, A.; Götz, F. Skin-Specific Unsaturated Fatty Acids Boost the Staphylococcus aureus Innate Immune Response. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, A.C.; Thurlow, L.R.; Richardson, A.R. Mechanisms Behind the Indirect Impact of Metabolic Regulators on Virulence Factor Production in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0206322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, P.; Boyd, J.M. Metabolic control of virulence factor production in Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2020, 55, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Bischoff, M.; Lattar, S.M.; Noto Llana, M.; Pfortner, H.; Niemann, S.; Geraci, J.; Van de Vyver, H.; Fraunholz, M.J.; Cheung, A.L.; et al. Sigma Factor SigB Is Crucial to Mediate Staphylococcus aureus Adaptation during Chronic Infections. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegmund, A.; Afzal, M.A.; Tetzlaff, F.; Keinhorster, D.; Gratani, F.; Paprotka, K.; Westermann, M.; Nietzsche, S.; Wolz, C.; Fraunholz, M.; et al. Intracellular persistence of Staphylococcus aureus in endothelial cells is promoted by the absence of phenol-soluble modulins. Virulence 2021, 12, 1186–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong Fok Lung, T.; Monk, I.R.; Acker, K.P.; Mu, A.; Wang, N.; Riquelme, S.A.; Pires, S.; Noguera, L.P.; Dach, F.; Gabryszewski, S.J.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus small colony variants impair host immunity by activating host cell glycolysis and inducing necroptosis. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, S.A.; Wong Fok Lung, T.; Prince, A. Pulmonary Pathogens Adapt to Immune Signaling Metabolites in the Airway. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, K.L.; Prince, A.S.; Wong Fok Lung, T. Immunometabolites Drive Bacterial Adaptation to the Airway. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 790574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Pöllath, C.; Siegmund, A.; Deinhardt-Emmer, S.; Hoerr, V.; Svensson, C.M.; Thilo Figge, M.; Monecke, S.; Löffler, B. Clinical S. aureus Isolates Vary in Their Virulence to Promote Adaptation to the Host. Toxins 2019, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missiakas, D.; Winstel, V. Selective Host Cell Death by Staphylococcus aureus: A Strategy for Bacterial Persistence. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 621733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, C.M.; Kielian, T. Crosstalk Between Staphylococcus aureus and Innate Immunity: Focus on Immunometabolism. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 621750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.J.; Heim, C.E.; Xi, X.; Attri, K.S.; Wang, D.; Zhang, W.; Singh, P.K.; Bronich, T.K.; Kielian, T. Monocyte metabolic reprogramming promotes pro-inflammatory activity and Staphylococcus aureus biofilm clearance. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, B.C.; Wu, C.H.; Gordon, N.C.; Cole, K.; Price, J.R.; Liu, E.; Sheppard, A.E.; Perera, S.; Charlesworth, J.; Golubchik, T.; et al. Severe infections emerge from commensal bacteria by adaptive evolution. Elife 2017, 6, 30637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, H.S.; Chatterjee, S.S.; Villaruz, A.E.; Dickey, S.W.; Tan, V.Y.; Chen, Y.; Sturdevant, D.E.; Ricklefs, S.M.; Otto, M. Mechanism of Gene Regulation by a Staphylococcus aureus Toxin. mBio 2016, 7, e01579-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchscherr, L.; Medina, E.; Hussain, M.; Volker, W.; Heitmann, V.; Niemann, S.; Holzinger, D.; Roth, J.; Proctor, R.A.; Becker, K.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus phenotype switching: An effective bacterial strategy to escape host immune response and establish a chronic infection. EMBO Mol. Med. 2011, 3, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winstel, V.; Kühner, P.; Salomon, F.; Larsen, J.; Skov, R.; Hoffmann, W.; Peschel, A.; Weidenmaier, C. Wall Teichoic Acid Glycosylation Governs Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Colonization. mBio 2015, 6, e00632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Wu, Y.; Yang, C.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Huang, W.; Zhu, X.Y.; Yan, Y.J.; Wang, J.X.; Zhu, T.; et al. Effect of nicotine on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and virulence factors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, F.; von Eiff, C.; Stoll, W.; Becker, K.; Rudack, C. Induction of CXC chemokines in A549 airway epithelial cells by trypsin and staphylococcal proteases—A possible route for neutrophilic inflammation in chronic rhinosinusitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2006, 144, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachse, F.; von Eiff, C.; Becker, K.; Steinhoff, M.; Rudack, C. Proinflammatory impact of Staphylococcus epidermidis on the nasal epithelium quantified by IL-8 and GRO-alpha responses in primary human nasal epithelial cells. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 145, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuck, B.A.; Beule, A.; Jobst, D.; Klimek, L.; Laudien, M.; Lell, M.; Vogl, T.J.; Popert, U. Guideline for “rhinosinusitis”-long version: S2k guideline of the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians and the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Hno 2018, 66, 38–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, L. Assessment and staging of nasal polyposis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1997, 117, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D.; et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sung, C.Y.; Lee, N.; Ni, Y.; Pihlajamäki, J.; Panagiotou, G.; El-Nezami, H. Probiotics modulated gut microbiota suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1306–E1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, D.T.; Franzosa, E.A.; Tickle, T.L.; Scholz, M.; Weingart, G.; Pasolli, E.; Tett, A.; Huttenhower, C.; Segata, N. MetaPhlAn2 for enhanced metagenomic taxonomic profiling. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 902–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.A.; McIver, L.J.; Rahnavard, G.; Thompson, L.R.; Schirmer, M.; Weingart, G.; Lipson, K.S.; Knight, R.; Caporaso, J.G.; Segata, N.; et al. Species-level functional profiling of metagenomes and metatranscriptomes. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumond, E.; Peron, S.; Daniel, N.; Le Gouar, Y.; Guédon, É.; Williams, D.L.; Le Loir, Y.; Jan, G.; Berkova, N. Development of innate immune memory by non-immune cells during Staphylococcus aureus infection depends on reactive oxygen species. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1138539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purves, J.; Hussey, S.J.K.; Corscadden, L.; Purser, L.; Hall, A.; Misra, R.; Selley, L.; Monks, P.S.; Ketley, J.M.; Andrew, P.W.; et al. Air pollution induces Staphylococcus aureus USA300 respiratory tract colonization mediated by specific bacterial genetic responses involving the global virulence gene regulators Agr and Sae. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 4449–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monecke, S.; Slickers, P.; Ehricht, R. Assignment of Staphylococcus aureus isolates to clonal complexes based on microarray analysis and pattern recognition. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 53, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monecke, S.; Coombs, G.; Shore, A.C.; Coleman, D.C.; Akpaka, P.; Borg, M.; Chow, H.; Ip, M.; Jatzwauk, L.; Jonas, D.; et al. A field guide to pandemic, epidemic and sporadic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 2003, 14, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.W. Package “Labdsv” Title Ordination and Multivariate Analysis for Ecology. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/labdsv/labdsv.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2024).

| Control Volunteers (N = 128) | Patients with CRS (N = 246) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | N | % | N | % | p * |

| Gender | 0.595 | ||||

| Female | 52 | 40.6 | 93 | 37.8 | |

| Male | 76 | 59.4 | 153 | 62.2 | |

| Smoking | 0.029 | ||||

| Yes | 39 | 30.5 | 37 | 15.0 | |

| No | 89 | 69.5 | 209 | 85.0 | |

| Allergy | 0.812 | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 41.4 | 107 | 43.5 | |

| No | 75 | 58.6 | 139 | 56.5 | |

| N-ERD | 0.002 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7.3 | |

| No | 128 | 100 | 228 | 92.7 | |

| Asthma | 0.003 | ||||

| Yes | 7 | 5.4 | 46 | 18.7 | |

| No | 121 | 94.6 | 200 | 81.3 | |

| Diabetes | 0.074 | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 12.5 | 9 | 3.7 | |

| No | 112 | 87.5 | 237 | 96.3 | |

| CRS type | NA | ||||

| CRSsNP | NA | NA | 166 | 67.5 | |

| CRSwNP | NA | NA | 80 | 32.5 | |

| Pre- or perioperative antibiotic treatment | 0.358 | ||||

| Yes | 23 | 18.0 | 59 | 24.0 | |

| No | 105 | 82.0 | 187 | 76.0 | |

| Mean ± SD | Median, Range | Mean ± SD | Median, Range | p ** | |

| Age, years | 53.1 ± 17.2 | 55, 18–89 | 49.7 ± 16.2 | 50, 18–83 | 0.108 |

| MALM score | NA | NA | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 2, 0–3 | NA |

| Bacterial Species | Fisher Test |

|---|---|

| Corynebacterium sp. | p = 0.003 ** |

| Staphylococcus coag. negative | p = 0.055 |

| Streptococcus sp. | p = 0.0009 *** |

| Enterobacteriaceae | p > 0.99 |

| Neisseria sp. | p = 0.42 |

| CRS Patient Isolates, Number | CRS Isolates, Percent | Control Isolates, Number | Control Isolates, Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species markers (gapA, katA, coA, nuc, spa, sbi) | 51 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

| agr-group I | 33 | 64.7 | 32 | 65.3 |

| agr-group II | 8 | 15.7 | 6 | 12.2 |

| agr-group III | 9 | 17.6 | 11 | 22.4 |

| agr-group IV | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| hld | 51 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

| tst1 | 7 | 13.7 | 12 | 24.5 |

| sea | 4 | 7.8 | 2 | 4.1 |

| sea (N315) = sep | 8 | 15.7 | 7 | 14.3 |

| seb | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| sec, sel | 7 | 13.7 | 4 | 8.2 |

| sed | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| see | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| seh | 2 | 3.9 | 5 | 10.2 |

| sej | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| sek, seq | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| ser | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| egc genes (seg, sei, selm, seln, selo, selu) | 27 | 52.9 | 27 | 55.1 |

| ORF CM14 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| lukF/S-hlg | 51 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

| lukF/S-PV | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| lukF-PV (P83)/lukM | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| lukD | 23 | 45.1 | 23 | 46.9 |

| lukE | 24 | 47.1 | 22 | 44.9 |

| lukX/Y | 51 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

| hla | 50 | 98.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

| sak | 39 | 76.5 | 35 | 71.4 |

| chp | 32 | 62.7 | 28 | 57.1 |

| scn | 49 | 96.1 | 43 | 87.8 |

| etA | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| etB | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| etD | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| edinA, edinC | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| edinB | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| ACME | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Capsule type 5 | 11 | 21.6 | 18 | 36.7 |

| Capsule type 8 | 40 | 78.4 | 31 | 63.3 |

| cna | 29 | 56.9 | 22 | 44.9 |

| sasG | 15 | 29.4 | 15 | 30.6 |

| CRS Patient Isolates, Number | CRS Isolates, Percent | Control Isolates, Number | Control Isolates, Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mecA * | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| SCCmec Iva * | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| mecC | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| blaZ | 29 | 56.9 | 37 | 75.5 |

| erm(A) | 3 | 5.9 | 3 | 6.1 |

| erm(B), erm(C), lnu(A), msrA | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| aacA-aphD | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| aadD, aphA3, sat | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| fusC, far1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| tet(K) | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| dfrA, mupR, tet(M), cat, cfr, fexA, van genes | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| qacC | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CRS Patient Isolates. Number | CRS Isolates. Percent | Control Isolates. Number | Control Isolates. Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC5 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| CC7 | 7 | 13.7 | 7 | 14.3 |

| CC8 | 3 | 5.9 | 4 | 8.2 |

| CC15 | 7 | 13.7 | 4 | 8.2 |

| CC20 | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CC22 | 2 | 3.9 | 2 | 4.1 |

| CC25 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| CC30 | 8 * | 15.7 | 7 | 14.3 |

| CC34 | 1 | 2.0 | 4 | 8.2 |

| CC45 | 12 | 23.5 | 8 | 16.3 |

| CC50 | 1 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CC97 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 6.1 |

| CC101 | 2 | 3.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| CC182 | 1 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| CC188 | 2 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.0 |

| CC398 | 3 | 5.9 | 3 | 6.1 |

| ST848 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.0 |

| TOTAL | 51 | 100.0 | 49 | 100.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tuchscherr, L.; Wendler, S.; Santhanam, R.; Priese, J.; Reissig, A.; Müller, E.; Ali, R.; Müller, S.; Löffler, B.; Monecke, S.; et al. Reduced Glycolysis and Cytotoxicity in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis as Strategies for Host Adaptation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042229

Tuchscherr L, Wendler S, Santhanam R, Priese J, Reissig A, Müller E, Ali R, Müller S, Löffler B, Monecke S, et al. Reduced Glycolysis and Cytotoxicity in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis as Strategies for Host Adaptation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(4):2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042229

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuchscherr, Lorena, Sindy Wendler, Rakesh Santhanam, Juliane Priese, Annett Reissig, Elke Müller, Rida Ali, Sylvia Müller, Bettina Löffler, Stefan Monecke, and et al. 2024. "Reduced Glycolysis and Cytotoxicity in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis as Strategies for Host Adaptation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 4: 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042229

APA StyleTuchscherr, L., Wendler, S., Santhanam, R., Priese, J., Reissig, A., Müller, E., Ali, R., Müller, S., Löffler, B., Monecke, S., Ehricht, R., & Guntinas-Lichius, O. (2024). Reduced Glycolysis and Cytotoxicity in Staphylococcus aureus Isolates from Chronic Rhinosinusitis as Strategies for Host Adaptation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(4), 2229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25042229