Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

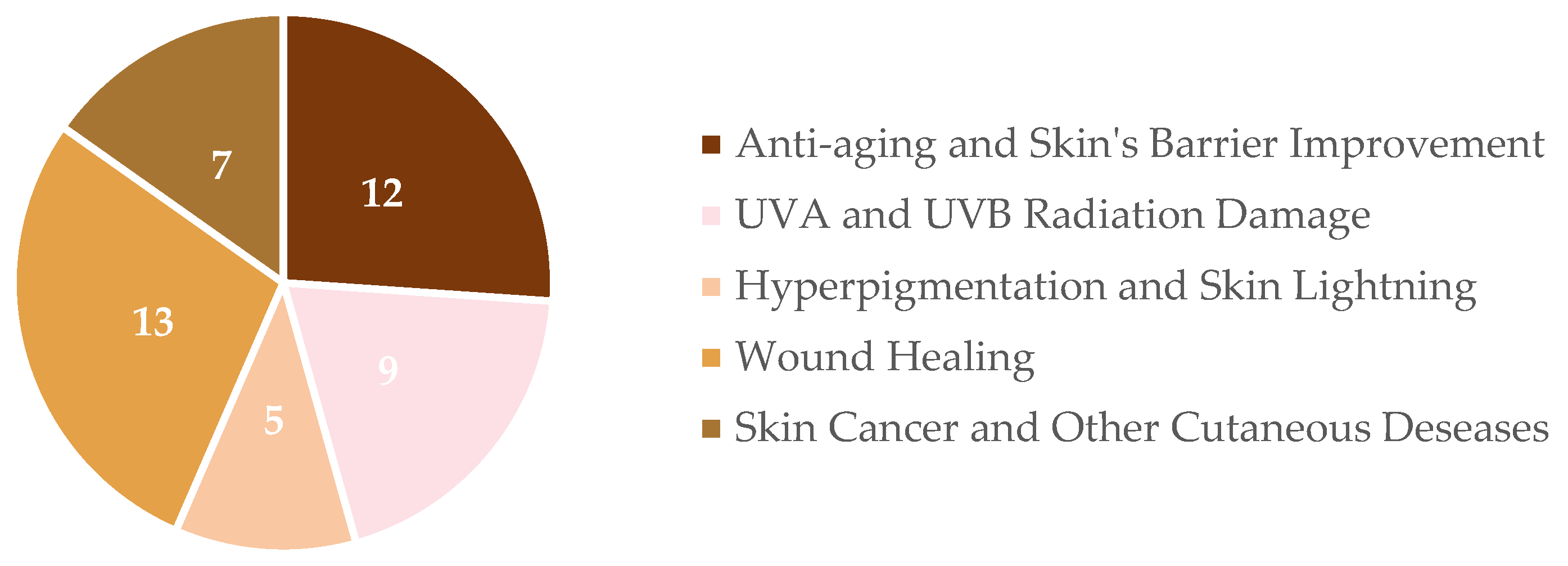

2. Studies Published in The Last Decade—An Overview

2.1. Research Methodology

2.2. Results

3. Hesperidin Extraction and Purification from Oranges’ Peel Waste

4. Application of Hesperidin’s Biological Activities on Skincare

4.1. Antiaging and Skin’s Barrier Improvement

| Hesperidin/ Extract Type | Hesperidin Levels Tested | Testing Model | Main Biological Properties | Formulation | Potential Applications | Molecular Pathways/ Other Relevant Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial hesperidin | ≈35–70% (w/v) | In vitro non-cellular assays | Radical scavenging activity increase in a dose-dependent manner. | Complex of hesperidin with modified silica (1:1, 1:2 or 2:1 (w/w)) | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Complex’s antioxidant properties were higher than free hesperidin | [23] |

| Rutaceae fruits extract | 1254.67 μg/mL | S. epidermidis E.coli P. acnes | Radical scavenging activity; Antibacterial activity against S. epidermidis, E. coli and P. acnes. | Mixed Rutaceae fruits hesperidin-rich ethanolic extract fermented with mushroom mycelium | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [35] |

| C. unshiu peel extract | 0.25–1% (w/v) | HDFs cells | MMP-1 expression decreases in a dose-dependent manner; Senescent cells decrease; Collagen biosynthesis increases. | C. unshiu peel extract fermented with S.commune | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [44] |

| Citrus sinensis peel bagasse | Corrosion tests: 100 µg/mL Collagenase assay: 0.08–0.9 mmol/L | FTS cells | Chelation activity; Collagenase inhibition; Antioxidant activity. | Nanoemulsion: hesperidin; glycerol; orange oil, poloxamer (Pluronic F127); and water. Nanoemulsion Silky Cream: BisPEG/PPG-16/16 PEG/PPG-16/16 dimethicone; caprylic/capric triglyceride (1%); muru muru butter (1%); cupuaçu butter (1%); andiroba oil (3%); GMS (2%); cetostearyl alcohol (3%); mineral oil (5%); carbopol ULTREZ 10 (0.2%); nano-emulsion (79.8%); triethanolamine (5 drops); vit E-acetate (0.05%); ethylhexylglicerin, phenoxy-ethanol (0.05%) | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Modulation of MMPs activities | [63] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 50 µM | HaCaT cells exposed to PM2.5 | Intracellular ROS levels reduction; Apoptotic index reduction; Protein carbonylation and intracellular vacuoles accumulation reversion; Reversion of elevated mitochondrial depolarization; Overall inhibitory effect on PM2.5-induced skin senescence and aging. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Cell viability restoration via PI3K/Akt activation; MAPK activation and autophagy/apoptosis-related protein expression mitigation; Increase in the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression; Cell arrest in the G0/G1 phase decrease; β-galactosidase activity and MMP-associated senescence decrease; Oxidation effects decreased by c-Jun and c-Fos protein levels reduction | [80,81] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.02% (w/v) | HaCaT cells | In vitro enhancement of antimicrobial peptide’s mRNA expression. | 0.02% hesperidin; 70% ethanol (w/v) | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Increase in epidermal differentiation-related protein expression (loricrin and filaggrin); β-glucocerebrosidase and glutathione reductase activity regulation | [84,85] |

| . | 1.03 mmol | In vitro non-cellular assays | Radical scavenging activity. | Hesperidin-conjugated pectins: pectin aqueous solution of 8 g (2.5 wt%); hesperidin intermediate (1.03 mmol) solution into a 7.5 wt% sodium hydroxide solution and epichlorohydrin (1.03 mmol) Hesperidin-conjugated pectins Hydrogels: pectin conjugates (5 wt% pectin solution) individually crosslinked with Ca2+, Zn2+, and Fe3+ (0.22 mM ionic solutions) | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Hesperidin’s ion-binding ability induced the crosslinking of the hydrogel conjugates | [86] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.05% (w/w) | In vitro non-cellular assays | Formulation’s bioadhesive properties improvement. | Biocomposites of cellulose, collagen, and hesperidin (4:1:0.05 (w/w)) | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [87] |

4.2. UVA and UVB Radiation-Induced Skin Damage

4.3. Skin’s Hyperpigmentation and Depigmentation Conditions

4.4. Wound Healing

4.5. Skin Cancer and Other Cutaneous Diseases

| Hesperidin/ Extract Type | Hesperidin Levels Tested | Testing Model | Main Biological Properties | Formulation | Potential Applications | Other Relevant Properties/ Molecular Pathways | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet orange peel extract | 0.05–1 mg/mL | A. flavus A. parasiticus A. niger A. ochraceous F. proliferitum P. verrucosum BJ-1 cells Cancerous cell lines (HCT-116/MCF7/HepG2) | Liposome protection against UV-induced peroxidation; DNA protection activity; Free hesperidin presents pro-oxidant activity against cancerous cells; Antifungal activity; Growth inhibition of MCF-7 and HepG-2; NPs reduced cytotoxic effects against normal cells (BJ-1). | Nanoparticles (NPs): hesperidin (16.5 g) and PEG (50 g) | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Hesperidin-loaded NPs enhanced protection capacity against DNA damage (maybe due to the alteration of the free hesperidin’s delivery, inside the cells, at the site of action) | [64] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 10–50 μM | Epidermoid carcinoma cell line (A431 cells) | Decreasing in A431 viability and colony-forming potential in a dose-dependent manner; A high number of A431 cells in the S phase; Augmented ROS levels, increased cytosolic Ca2+ level, and reduced mitochondrial membrane potential level in A431; DNA breakage and non-apoptotic cell death inducing in A431. | N/A | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Cyclin D, CDK2, and thymidylate synthase expression decreased in A431 cells; Reduced ATP levels by up to 40% in A431 cells | [73] |

| Commercial hesperidin | In vivo (oral intake): 125–500 mg/Kg/day In vitro: 5–20 μg/mL | Mouse HaCaT cells | Reduced keratinocyte excessive proliferation and ameliorated abnormal differentiation of epidermal cells in in vitro psoriasis-like-induced model; Reduced the pathological changes of psoriasiform dermatitis by reducing localized inflammatory cytokine expression in vivo; Reduce excessive cell proliferation and differentiation in skin lesions in a dose-dependent manner in vivo. | N/A | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Inhibition of tumor cell proliferation in a time/dosage-dependent manner; Hesperidin was found to be present in the stratum corneum and upper spinous layer after each dose | [115] |

| Commercial hesperidin | Formulation’s oral intake: 100–400 mg/Kg/day | Swiss albino mice | Reducing of the tumor incidence in a dose-dependent manner; Reduced average number of tumors in a dose-dependent manner; Reduced neoplastic transformation in skin cells. | Hesperidin in saline water containing 0.5% (w/v) carboxymethyl-cellulose | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Catalase and SOD activity enhancement in skin tumors after 24 weeks of treatment; GSH levels and activity increase in a dose-dependent manner; Reduction in the expression of Rassf7, Nrf2, PARP, and NF-κB genes in a dose-dependent manner; Inhibition of MDA in skin tumors, in a dose-dependent manner, leads to a lipid peroxidation decrease | [116] |

| Commercial hesperidin | Oral intake: 0.1% (w/w) | Splenocytes from NC/Nga mice | No atopic dermatitis-induced skin lesions observed after treatment; Clinical scores (evaluation of atopic dermatitis symptoms) of hesperidin-fed mice increased until 10 weeks of age. | N/A | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Increase in IgE serum levels; Decrease in IFN-c, IL-17 and IL-10 levels | [118] |

| Hesperidin from micronized purified flavonoid fraction | Oral intake: 50 mg | Human 45-year-old male (case report) | Treatment improved the patient pigmented purpuric dermatoses lesions, after 2 weeks. | Oral intake: diosmin (450 mg), hesperidin (50 mg), E. prostata extract (100 mg), and calcium dobesilate (500 mg) | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Surface expression of monocyte or neutrophil CD62L reduction; Leukocyte activation inhibition; VEGF expression downregulation; Decreasing of TNF-α, MMPs and NGAL expression; Production of oxygen free radical and lipid peroxidation inhibition | [119] |

| Hesperidin from orange waste | 5–45 μmol/L | A375 cells CHL01 cells SKMEL147 cells | DPPH scavenging activity; No cytotoxicity to all cell lines at the tested concentrations. | Nanostructured lipid carriers: cupuaçu butter mixed with buriti oil, anhydrous lanolin (10% v/v), and L-hesperidin (4 mmol) | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | N/A | [121] |

5. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carvalho, M.J.; Oliveira, A.L.; Pedrosa, S.S.; Pintado, M.; Madureira, A.R. Potential of sugarcane extracts as cosmetic and skincare ingredients. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 169, 113625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.-W.; Lee, C.-H.; Min, H.-J.; Kim, D.-D.; Kim, D.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, H.-W. Skincare Device Product Design Based on Factor Analysis of Korean Anthropometric Data. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, R.I.; Ezzat, S.M.; Aborehab, N.M.; Ragab, M.F.; Mohamed, D.; Hashad, A.; Attia, D.; Salama, M.M.; El Bishbishy, M.H. Downregulation of MMP1 expression mediates the anti-aging activity of Citrus sinensis peel extract nanoformulation in UV induced photoaging in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, M.-Q.; Yang, B.; Elias, P.M. Benefits of Hesperidin for Cutaneous Functions. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 2676307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Pang, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from human dermal fibroblast effectively ameliorate skin photoaging via miRNA-22-5p-GDF11 axis. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.V.; Sousa, R.O.; Carvalho, A.C.; Alves, A.L.; Marques, C.F.; Cerqueira, M.T.; Reis, R.L.; Silva, T.H. Potential of Atlantic Codfish (Gadus morhua) Skin Collagen for Skincare Biomaterials. Molecules 2023, 28, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.; Jatana, G.K.; Sonthalia, S. Cosmeceuticals. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, T.M.; Mijaljica, D.; Townley, J.P.; Spada, F.; Harrison, I.P. Vehicles for Drug Delivery and Cosmetic Moisturizers: Review and Comparison. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzi, D. Cosmetics Industry—Statistics & Facts; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Market Research. Dermatological Therapeutics Market—Growth, Trends, COVID-19 Impact, and Forecasts (2022–2027); MOI16936445; Market Research: Rockville, MD, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.marketresearch.com/ (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Puyana, C.; Chandan, N.; Tsoukas, M. Applications of bakuchiol in dermatology: Systematic review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 6636–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, M.-C.; Grisel, M.; Gore, E. Multifunctional active ingredient-based delivery systems for skincare formulations: A review. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2022, 217, 112676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards Circular Economy; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Isle of Wight, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, J.O.; Sanches, V.L.; Viganó, J.; de Souza Mesquita, L.M.; de Souza, M.C.; da Silva, L.C.; Acunha, T.; Faccioli, L.H.; Rostagno, M.A. Integration of pressurized liquid extraction and in-line solid-phase extraction to simultaneously extract and concentrate phenolic compounds from lemon peel (Citrus limon L.). Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, E.; Monteiro, M. Simultaneous HPLC determination of flavonoids and phenolic acids profile in Pêra-Rio orange juice. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proteggente, A.R.; Basu-Modak, S.; Kuhnle, G.; Gordon, M.J.; Youdim, K.; Tyrrell, R.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Hesperetin glucuronide, a photoprotective agent arising from flavonoid metabolism in human skin fibroblasts. Photochem. Photobiol. 2003, 78, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favela-Hernández, J.M.J.; González-Santiago, O.; Ramírez-Cabrera, M.A.; Esquivel-Ferriño, P.C.; Camacho-Corona, M.D.R. Chemistry and Pharmacology of Citrus sinensis. Molecules 2016, 21, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby-Figueroa, R.; Nardi, M.; Sindona, G.; Conidi, C.; Cassano, A. A Multivariate Statistical Analyses of Membrane Performance in the Clarification of Citrus Press Liquor. ChemEngineering 2019, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Magalhães, D.; Campos, D.A.; Porretta, S.; Dellapina, G.; Poli, G.; Istanbullu, Y.; Demir, S.; San Martín, Á.M.; García-Gómez, P.; et al. Innovative Processing Technologies to Develop a New Segment of Functional Citrus-Based Beverages: Current and Future Trends. Foods 2022, 11, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magalhães, D.; Vilas-Boas, A.A.; Teixeira, P.; Pintado, M. Functional Ingredients and Additives from Lemon by-Products and Their Applications in Food Preservation: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C.; Maugeri, A.; Lombardo, G.E.; Musumeci, L.; Barreca, D.; Rapisarda, A.; Cirmi, S.; Navarra, M. The Second Life of Citrus Fruit Waste: A Valuable Source of Bioactive Compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bino, A.; Vicentini, C.B.; Vertuani, S.; Lampronti, I.; Gambari, R.; Durini, E.; Manfredini, S.; Baldisserotto, A. Novel Lipidized Derivatives of the Bioflavonoid Hesperidin: Dermatological, Cosmetic and Chemopreventive Applications. Cosmetics 2018, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binkowska, I. Hesperidin: Synthesis and characterization of bioflavonoid complex. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohbakhsh, A.; Parhiz, H.; Soltani, F.; Rezaee, R.; Iranshahi, M. Molecular mechanisms behind the biological effects of hesperidin and hesperetin for the prevention of cancer and cardiovascular diseases. Life Sci. 2015, 124, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breceda-Hernández, T.; Martinez-Ruiz, N.; Serna-Guerra, L.; Hernández-Carrillo, J. Effect of a pectin edible coating obtained from orange peels with lemon essential oil on the shelf life of table grapes (Vitis vinifera L. var. Red Globe). Int. Food Res. J. 2020, 27, 585–596. [Google Scholar]

- Teigiserova, D. The Hidden Value of Food Waste: A Bridge to Sustainable Development in the Circular Economy. Ph.D. Thesis, Aarhus Universitet, Aarhus, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abou Baker, D.H.; Ibrahim, B.M.M.; Abdel-Latif, Y.; Hassan, N.S.; Hassan, E.M.; El Gengaihi, S. Biochemical and pharmacological prospects of Citrus sinensis peel. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, N.; Sinha, M.; Sharma, K.; Koteswararao, R.; Cho, M.H. Modern Extraction and Purification Techniques for Obtaining High Purity Food-Grade Bioactive Compounds and Value-Added Co-Products from Citrus Wastes. Foods 2019, 8, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Vishvakarma, R.; Gautam, K.; Vimal, A.; Kumar Gaur, V.; Farooqui, A.; Varjani, S.; Younis, K. Valorization of citrus peel waste for the sustainable production of value-added products. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 351, 127064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, E.; Debruyne, C.; De Troyer, O.; Rogiers, V.; Vinken, M.; Vanhaecke, T. Screening of repeated dose toxicity data in safety evaluation reports of cosmetic ingredients issued by the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety between 2009 and 2019. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 3723–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.-H. Optimizing Procedures of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Waste Orange Peels by Response Surface Methodology. Molecules 2022, 27, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, M.M.; David, J.M.; Cortez, M.V.M.; Leite, J.L.; da Silva, G.S.B. A High-Yield Process for Extraction of Hesperidin from Orange (Citrus sinensis L. osbeck) Peels Waste, and Its Transformation to Diosmetin, A Valuable and Bioactive Flavonoid. Waste Biomass Valorization 2021, 12, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcelik, F.; Akan, E.; Kinik, O. Use of Cornelian cherry, hawthorn, red plum, roseship and pomegranate juices in the production of water kefir beverages. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’hiri, N.; Ioannou, I.; Mihoubi Boudhrioua, N.; Ghoul, M. Effect of different operating conditions on the extraction of phenolic compounds in orange peel. Food Bioprod. Process. 2015, 96, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, K.M. Study on Functional Natural Materials to Improve for Human Health—Comparison Analysis of Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity of Fermented Rutaceas Fruits Extract. Rev. Soc. Sci. 2021, 6, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadis, V.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Kotsou, K.; Palaiogiannis, D.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Optimization of the Extraction Parameters for the Isolation of Bioactive Compounds from Orange Peel Waste. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louati, I.; Bahloul, N.; Besombes, C.; Allaf, K.; Kechaou, N. Instant controlled pressure-drop as texturing pretreatment for intensifying both final drying stage and extraction of phenolic compounds to valorize orange industry by-products (Citrus sinensis L.). Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 114, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Lee, Y.R. Extraction, characterization and biological activity of citrus flavonoids. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Benohoud, M.; Galani Yamdeu, J.H.; Gong, Y.Y.; Orfila, C. Green extraction of polyphenols from citrus peel by-products and their antifungal activity against Aspergillus flavus. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jridi, M.; Boughriba, S.; Abdelhedi, O.; Nciri, H.; Nasri, R.; Kchaou, H.; Kaya, M.; Sebai, H.; Zouari, N.; Nasri, M. Investigation of physicochemical and antioxidant properties of gelatin edible film mixed with blood orange (Citrus sinensis) peel extract. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.-N.; Yu, M.-W.; Ho, C.-T. Tyrosinase inhibitory components of immature calamondin peel. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsouko, E.; Maina, S.; Ladakis, D.; Kookos, I.K.; Koutinas, A. Integrated biorefinery development for the extraction of value-added components and bacterial cellulose production from orange peel waste streams. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumi, H.; Jo, A.; Nakata, D.; Terao, K.; Uekaji, Y. Preparing Aqueous Solution Useful for Preparing Cosmetics and Foodstuff Involves Adding Super Dissolution Aid, Cyclodextrin and Fat-Soluble Substance or Cyclodextrin Complex of Fat-Soluble Substance, to Water. International Patent Application No. WO2012105546A1, 31 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.T.; Ko, H.J.; Kim, G.B.; Pyo, H.B.; Lee, G.S. Protective Effects of Fermented Citrus Unshiu Peel Extract against Ultraviolet-A-induced Photoageing in Human Dermal Fibrobolasts. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-K.; Park, N.-H.; Hwang, J.-S. Skin Lightening Effect of the Dietary Intake of Citrus Peel Extract Against UV-Induced Pigmentation. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19859979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrales, F.M.; Silveira, P.; Barbosa, P.d.P.M.; Ruviaro, A.R.; Paulino, B.N.; Pastore, G.M.; Macedo, G.A.; Martinez, J. Recovery of phenolic compounds from citrus by-products using pressurized liquids—An application to orange peel. Food Bioprod. Process. 2018, 112, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vázquez, L.; Lozano, M.V.; Rodríguez-Robledo, V.; González-Fuentes, J.; Marcos, P.; Villaseca, N.; Arroyo-Jiménez, M.M.; Santander-Ortega, M.J. Pressurized Extraction as an Opportunity to Recover Antioxidants from Orange Peels: Heat treatment and Nanoemulsion Design for Modulating Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2021, 26, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kantar, S.; Rajha, H.N.; El Khoury, A.; Koubaa, M.; Nachef, S.; Debs, E.; Maroun, R.G.; Louka, N. Phenolic Compounds Recovery from Blood Orange Peels Using a Novel Green Infrared Technology and Their Effect on the Inhibition of Aspergillus flavus Proliferation and Aflatoxin B1 Production. Molecules 2022, 27, 8061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuin, V.G.; Ramin, L.Z.; Segatto, M.L.; Stahl, A.M.; Zanotti, K.; Forim, M.R.; Silva, M.F.d.G.F.d.; Fernandes, J.B. To separate or not to separate: What is necessary and enough for a green and sustainable extraction of bioactive compounds from Brazilian citrus waste. Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmau, E.; Rosselló, C.; Eim, V.; Ratti, C.; Simal, S. Ultrasound-Assisted Aqueous Extraction of Biocompounds from Orange Byproduct: Experimental Kinetics and Modeling. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Calderon, A.; Cortes, C.; Zulueta, A.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J. Green solvents and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of bioactive orange (Citrus sinensis) peel compounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scurria, A.; Sciortino, M.; Garcia, A.R.; Pagliaro, M.; Avellone, G.; Fidalgo, A.; Albanese, L.; Meneguzzo, F.; Ciriminna, R.; Ilharco, L.M. Red Orange and Bitter Orange IntegroPectin: Structure and Main Functional Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, C.; Cameron, R.G.; Manthey, J.A. Study of Static Steam Explosion of Citrus sinensis Juice Processing Waste for the Isolation of Sugars, Pectic Hydrocolloids, Flavonoids, and Peel Oil. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2019, 12, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachos-Perez, D.; Baseggio, A.M.; Mayanga-Torres, P.C.; Maróstica, M.R.; Rostagno, M.A.; Martínez, J.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Subcritical water extraction of flavanones from defatted orange peel. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 138, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temiz, B.; Agalar, H.G. Evaluation of radical scavenging and anti-tyrosinase activity of some Citrus fruits cultivated in Turkey via in vitro methods and high-performance thin-layer chromatography-effect-directed analysis. JPC–J. Planar Chromatogr.–Mod. TLC 2022, 35, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Pandey, P.; Gupta, R.; Roshan, S.; Garg, A.; Shukla, A.; Pasi, A. Isolation and characterization of hesperidin from orange peel. Indo Am. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 2013, 3892–3897. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrzynska, K. Hesperidin: A Review on Extraction Methods, Stability and Biological Activities. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, J.V., Jr.; Macedo, G.A. Simultaneous extraction and biotransformation process to obtain high bioactivity phenolic compounds from brazilian citrus residues. Biotechnol. Prog. 2015, 31, 1273–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-H.; García-Martín, J.F.; Broncano Lavado, M.; López-Barrera, M.d.C.; Álvarez-Mateos, P. Evaluation of different solvents on flavonoids extraction efficiency from sweet oranges and ripe and immature Seville oranges. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 3123–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, E.; Rosales-Conrado, N.; León-González, M.E.; Madrid, Y. Citrus peels waste as a source of value-added compounds: Extraction and quantification of bioactive polyphenols. Food Chem. 2019, 295, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakka, A.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D.P. Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin as a Green Co-Solvent in the Aqueous Extraction of Polyphenols from Waste Orange Peels. Beverages 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-C.; Liu, K.-C.; Chiou, Y.-L. Melanogenesis of murine melanoma cells induced by hesperetin, a Citrus hydrolysate-derived flavonoid. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 653–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanisic, D.; Liu, L.H.B.; dos Santos, R.V.; Costa, A.F.; Durán, N.; Tasic, L. New Sustainable Process for Hesperidin Isolation and Anti-Ageing Effects of Hesperidin Nanocrystals. Molecules 2020, 25, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Aboul-Enein, A.; abou-Elella, F.; Salem, S.; Aly, H.; Nassrallah, A.; Salama, D.Z. Nano-formulations of hesperidin and essential oil extracted from sweet orange peel: Chemical Properties and Biological Activities. Egypt. J. Chem. 2021, 64, 5373–5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Luo, F.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Sun, C.; Chen, K. Chemopreventive effect of flavonoids from Ougan (Citrus reticulata cv. Suavissima) fruit against cancer cell proliferation and migration. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 10, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, M.-J.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, K.S.; Park, K.J.; Park, S.M.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.-G. Down-regulation of tyrosinase, TRP-1, TRP-2 and MITF expressions by citrus press-cakes in murine B16 F10 melanoma. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razola-Díaz, M.d.C.; Guerra-Hernández, E.J.; Rodríguez-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Caravaca, A.M.; García-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction via Sonotrode of Phenolic Compounds from Orange By-Products. Foods 2021, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cypriano, D.Z.; da Silva, L.L.; Tasic, L. High value-added products from the orange juice industry waste. Waste Manag. 2018, 79, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving the pressing extraction of polyphenols of orange peel by pulsed electric fields. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 17, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokić, S.; Molnar, M.; Cikoš, A.-M.; Jakovljević, M.; Šafranko, S.; Jerković, I. Separation of selected bioactive compounds from orange peel using the sequence of supercritical CO2 extraction and ultrasound solvent extraction: Optimization of limonene and hesperidin content. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 2799–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilali, S.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Ruiz, K.; Hejjaj, A.; Ait Nouh, F.; Idlimam, A.; Bily, A.; Mandi, L.; Chemat, F. Green Extraction of Essential Oils, Polyphenols, and Pectins from Orange Peel Employing Solar Energy: Toward a Zero-Waste Biorefinery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 11815–11822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Jee-Young, L.; Ha-Yeon, L.; Ky-Youb, N.; JoongIl, P.; Min, L.S.; Eun, K.J.; Dong, L.J.; Sung, H.J. Hesperidin Suppresses Melanosome Transport by Blocking the Interaction of Rab27A-Melanophilin. Korean Soc. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 21, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X. Hesperidin-triggered necrosis-like cell death in skin cancer cell line A 431 might be prompted by ROS mediated alterations in mitochondrial membrane potential. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2018, 11, 1948–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, S.; Gray, R.; Hester, S.; Mastaloudis, A.; Kern, D.; Namkoong, J.; Draelos, Z.D. Nutritional supplement improves skin health. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, S.R.K.M.; Piao, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Ryu, Y.S.; Han, X.; Oh, M.C.; Jung, U.; Kim, I.G.; Hyun, J.W. Hesperidin Attenuates Ultraviolet B-Induced Apoptosis by Mitigating Oxidative Stress in Human Keratinocytes. Biomol. Ther. 2016, 24, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganceviciene, R.; Liakou, A.I.; Theodoridis, A.; Makrantonaki, E.; Zouboulis, C.C. Skin anti-aging strategies. Dermato-Endocrinology 2012, 4, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhag, S.; Nayak, A.; Narayan, R.; Nayak, U.Y. Anti-aging and Sunscreens: Paradigm Shift in Cosmetics. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 9, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Im, A.R.; Kim, S.-M.; Kang, H.-S.; Lee, J.D.; Chae, S. The flavonoid hesperidin exerts anti-photoaging effect by downregulating matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 expression via mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)-dependent signaling pathways. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaru, E.; Watanabe, M.; Nomura, Y. Dietary immature Citrus unshiu alleviates UVB-induced photoaging by suppressing degradation of basement membrane in hairless mice. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, H.M.U.L.; Piao, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Zhen, A.X.; Fernando, P.D.S.M.; Kang, H.K.; Yi, J.M.; Hyun, J.W. Hesperidin Exhibits Protective Effects against PM2.5-Mediated Mitochondrial Damage, Cell Cycle Arrest, and Cellular Senescence in Human HaCaT Keratinocytes. Molecules 2022, 27, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, P.D.S.M.; Piao, M.J.; Kang, K.A.; Zhen, A.X.; Herath, H.M.U.L.; Kang, H.K.; Choi, Y.H.; Hyun, J.W. Hesperidin Protects Human HaCaT Keratinocytes from Particulate Matter 2.5-Induced Apoptosis via the Inhibition of Oxidative Stress and Autophagy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, S.E.; Lee, G.-Y. Hesperidin, A Popular Antioxidant Inhibits Melanogenesis via Erk1/2 Mediated MITF Degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18384–18395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, G.; Mauro, T.; Zhai, Y.; Kim, P.; Cheung, C.; Hupe, M.; Crumrine, D.; Elias, P.; Man, M.-Q. Topical Hesperidin Enhances Epidermal Function in an Aged Murine Model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 135, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.; Mauro, T.M.; Kim, P.L.; Hupe, M.; Zhai, Y.; Sun, R.; Crumrine, D.; Cheung, C.; Nuno-Gonzalez, A.; Elias, P.M.; et al. Topical hesperidin prevents glucocorticoid-induced abnormalities in epidermal barrier function in murine skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.H.; Man, M.N.; Man, W.Y.; Zhu, W.Y.; Hupe, M.; Park, K.; Crumrine, D.; Elias, P.M.; Man, M.Q. Topical hesperidin improves epidermal permeability barrier function and epidermal differentiation in normal murine skin. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 21, 337–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Halake, K.; Lee, J. Antioxidant and ion-induced gelation functions of pectins enabled by polyphenol conjugation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghel, N.; LazĂR, S.; Ciubotaru, B.-I.; Verestiuc, L.; Spiridon, I. New Cellulose-Based Materials as Transdermal Transfer Systems for Bioactive Substances. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2019, 53, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, X.-f.; Lu, J.; Zhou, B.-R.; Luo, D. Hesperidin ameliorates UV radiation-induced skin damage by abrogation of oxidative stress and inflammatory in HaCaT cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 165, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.M.; Im, A.R.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, T.; Ji, K.Y.; Park, D.H.; Chae, S. Hesperidin Inhibits UVB-Induced VEGF Production and Angiogenesis via the Inhibition of PI3K/Akt Pathway in HR-1 Hairless Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 44, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, P.-D.; Kim, H.-M. Antiinflammatory Effects of Traditional Korean Medicine, JinPi-tang and Its Active Ingredient, Hesperidin in HaCaT cells. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacatusu, I.; Arsenie, L.V.; Badea, G.; Popa, O.; Oprea, O.; Badea, N. New cosmetic formulations with broad photoprotective and antioxidative activities designed by amaranth and pumpkin seed oils nanocarriers. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 123, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhase, A.S.; Khadbadi, H.S.; Saboo, S.S. Formulation and Evaluation of Vanishing Herbal Cream of Crude Extract. Am. J. Ethnomed. 2014, 1, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Rowny, K.; Smigielska, K.; Zdroik, K.; Ostrowska, B.; Debowska, R.; Rogiewicz, K.; Eris, I. Wide spectrum photoprotection in skin with acne, rosacea and after aesthetic treatments. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, S312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivasaraun, U.V.; Sureshkumar, R.; Karthika, C.; Puttappa, N. Flavonoids as adjuvant in psoralen based photochemotherapy in the management of vitiligo/leucoderma. Med. Hypotheses 2018, 121, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagher, Z.; Ehterami, A.; Safdel, M.H.; Khastar, H.; Semiari, H.; Asefnejad, A.; Davachi, S.M.; Mirzaii, M.; Salehi, M. Wound healing with alginate/chitosan hydrogel containing hesperidin in rat model. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoukens, G. 5—Bioactive dressings to promote wound healing. In Advanced Textiles for Wound Care; Rajendran, S., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2009; pp. 114–152. [Google Scholar]

- Boateng, J.S.; Matthews, K.H.; Stevens, H.N.E.; Eccleston, G.M. Wound healing dressings and drug delivery systems: A review. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 2892–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, L.; Koivisto, L.; Heino, J.; Larjava, H. Chapter 50—Cell and Molecular Biology of Wound Healing. In Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences; Vishwakarma, A., Sharpe, P., Shi, S., Ramalingam, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 669–690. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsner, R.S.; Baquerizo Nole, K.L.; Fox, J.D.; Liu, S.N. Healing Refractory Venous Ulcers: New Treatments Offer Hope. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, J.; Renault, J.; Domain, R.; Bojarski, K.K.; Chazeirat, T.; Saidi, A.; Leblanc, E.; Nizard, C.; Samsonov, S.A.; Kurfurst, R.; et al. Modulation of the expression and activity of cathepsin S in reconstructed human skin by neohesperidin dihydrochalcone. Matrix Biol. 2022, 107, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujitha, Y.; Muzib, Y. Preparation of Topical Nano Gel Loaded with Hesperidin Emusomoes: In vitro and in vivo studies. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2020, 10, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Sheikh, A.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Kesharwani, P. Amelioration of Full-Thickness Wound Using Hesperidin Loaded Dendrimer-Based Hydrogel Bandages. Biosensors 2022, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabeiryureilai, M.; Lalrinzuali, K.; Jagetia, G.C. NF-κB and COX-2 repression with topical application of hesperidin and naringin hydrogels augments repair and regeneration of deep dermal wounds. Burns 2022, 48, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessels, Q.; Pretorius, E.; Smith, C.M.; Nel, H. The potential of a niacinamide dominated cosmeceutical formulation on fibroblast activity and wound healing in vitro. Int. Wound J. 2014, 11, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Hu, Y.; Chang, L.; Xu, S.; Mei, X.; Chen, Z. Electrospinning of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory Ag@hesperidin core-shell nanoparticles into nanofibers used for promoting infected wound healing. Regen. Biomater. 2022, 9, rbac012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguzturk, H.; Ciftci, O.; Taslidere, A.; Turtay, M.G.; Gurbuz, S.; Basak, N.; Firat, C.; Yucel, N.; Guven, T. Investigating the Therapeutic Effects of Flavonoid-Structured Hesperidin in Acute Burn Traumas. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2018, 27, 5446–5454. [Google Scholar]

- Wessels, Q. Collagen-based scaffold as a delivery system for a niacinamide dominated formulation without loss of resistance against enzymatic degradation. Int. J. Biomed. Eng. Technol. 2016, 20, 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddadi, G.; Abbaszadeh, A.; Mosleh-Shirazi, M.A.; Okhovat, M.A.; Salajeghe, A.; Ghorbani, Z. Evaluation of the effect of hesperidin on vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in rat skin animal models following cobalt-60 gamma irradiation. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018, 14, S1098–S1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Kandhare, A.D.; Mukherjee, A.A.; Bodhankar, S.L. Hesperidin, a plant flavonoid accelerated the cutaneous wound healing in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: Role of TGF-ß/Smads and Ang-1/Tie-2 signaling pathways. EXCLI J. 2018, 17, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, T.; Fu, A.; Mao, Z.; Yi, L.; Tang, S.; Yang, J. Hesperidin enhances angiogenesis via modulating expression of growth and inflammatory factor in diabetic foot ulcer in rats. Eur. J. Inflamm. 2018, 16, 2058739218775255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.V.; Hema, G.; Vyshnavi, G.N.; Blessy, M.S. Evaluation of wound healing activity of hesperidin isolated from citrus fruits peel. In Proceedings of the International Journal of Life Science and Pharma Research, Mangalagiri, India, 17–18 December 2019; pp. 736–741. [Google Scholar]

- Jangde, R.; Elhassan, G.O.; Khute, S.; Singh, D.; Singh, M.; Sahu, R.K.; Khan, J. Hesperidin-Loaded Lipid Polymer Hybrid Nanoparticles for Topical Delivery of Bioactive Drugs. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, M. CHAPTER 15—Basal cell carcinoma. In Clinical Ophthalmic Oncology; Singh, A.D., Damato, B.E., Pe’er, J., Murphree, A.L., Perry, J., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Edinburgh, UK, 2007; pp. 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, L. Metastatic melanoma and rare melanoma variants: A review. Pathology 2022, 55, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, X.; Zhang, L.; Meng, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, M.; Zhai, C.; Liu, Z.; Di, T.; Zhang, L.; et al. Hesperidin inhibits keratinocyte proliferation and imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like dermatitis via the IRS-1/ERK1/2 pathway. Life Sci. 2019, 219, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vabeiryureilai, M.; Lalrinzuali, K.; Jagetia, G.C. Chemopreventive effect of hesperidin, a citrus bioflavonoid in two stage skin carcinogenesis in Swiss albino mice. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Pigeon, H.; Garidou, L.; Galliano, M.F.; Delga, H.; Aries, M.F.; Duplan, H.; Bessou-Touya, S.; Castex-Rizzi, N. Effects of dextran sulfate, 4-t-butylcyclohexanol, pongamia oil and hesperidin methyl chalcone on inflammatory and vascular responses implicated in rosacea. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashio, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Miyamoto, J.; Kometani, T.; Suzuki, T.; Tanabe, S. Hesperidin inhibits development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice by suppressing Th17 activity. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Sardana, K.; Kishan Gautam, R. Venoprotective drugs in pigmented purpuric dermatoses: A case report. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1580–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassino, E.; Antoniotti, S.; Gasparri, F.; Munaron, L. Effects of flavonoid derivatives on human microvascular endothelial cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 2831–2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, N.; Costa, A.F.; Stanisic, D.; Bernardes, J.S.; Tasic, L. Nanotoxicity and Dermal Application of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Loaded with Hesperidin from Orange Residue. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1323, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hesperidin/ Extract Type | Hesperidin Levels Tested | Testing Model | Main Biological Properties | Formulation | Potential Applications | Molecular Pathways/ Other Relevant Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.0125–1 mM | HaCaT cells | ROS scavenging activity increases in a dose-dependent manner; UVB absorption activity; DNA protection against UVB; Optimal hesperidin concentration: 50 μM. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Mitochondrial membrane depolarization regulation by apoptotic pathways inhibition; Caspase-3, caspase-9, and BAX downregulation; Upregulated expression of Bcl-2; Prevention of protein oxidation against UVB-induced ROS | [75] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 10–320 μg/mL | HaCaT cells | Cell viability increases in a concentration-dependent manner; Cell growth enhancement after inhibition by UVA; Enhancement of SOD activity; Reduction in ROS. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Reduction in MDA content; Downregulation of TNF-α mRNA/ protein, IL-1β mRNA/protein, and IL-6 mRNA/protein expression; Increase in T-AOC levels; Potential as a sunscreen agent | [88] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 5–20 μM | HEKs cells HDFs cells | In vitro inhibition of UVB-induced angiogenesis. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Repression of MMP-9, MMP-13, and VEGF expression; Regulation of MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways | [89] |

| Hesperidin from Citrus unshiu | 20 µg/mL | HaCaT cells | Regulation of inflammatory response. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Downregulation of IL-8 and TNF-α mRNA/protein expression; Inhibition of NF-ƙB/IƙBα signal cascade; Inhibition of p38 MAPK phosphorylation; Inhibition of COX-2 activation | [90] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.3% (w/v) | In vitro non-cellular assays | Inhibition of short-life radicals; Inhibition of ABTS radical; Absorption of 99% UVB radiation and 83% UVA radiation. | NLCs: amaranth oil; pumpkin seed oil; 7% UVA filter; diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate; 7% UVB filter; ethylhexyl salicylate; and 3% hesperidin. NLCs-Carbol gel (ratio 1:1) cosmetic formulation: final composition of 3.17% diethylamino-hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate, 3.17% ethylhexyl salicylate; and 1.13% hesperidin | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | In vitro, hesperidin presented a burst pattern with an accelerated release from the NLCs | [91] |

| Citrus sinesis L. peel extract | 500–1000 mg of extract | In vitro non-cellular assays | In vitro inhibition activities of DPPH radical, elastase and collagenase. | NLCs optimal formulation: cocoa butter/olive oil and 1000 mg extract Extract-NLCs cream: clove (Eugenia caryophyllus), nagarmotha (Cyperus scariosus), tulsi (Ocimum sanctum), nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), linseed (Linum usitatissium), wheat grains, cereals (Triticum aestivum), neem (Azadirachta indica), ethanol, stearic acid, potassium hydroxide, sodium carbonate, glycerin, water, perfume | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [3,92] |

| Commercial hesperidin | N/A | In vivo trials: dermatological assessment, instrumental skin analysis and satisfaction survey | High antioxidant activity; Absorption of UVA, HEV, and IR radiation; Skin barrier functions for protection; Reduction in erythema, skin irritability and visibility of telangiectasia. | Cosmetic product containing hesperidin and SPF 50+ | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [93] |

| Hesperidin/ Extract Type | Hesperidin Levels Tested | Testing Model | Main Biological Properties | Formulation | Potential Applications | Molecular Pathways/ Other Relevant Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrus mitis blanco peel water extract | Fraction reach in hesperidin 0.5 mg/mL | In vitro non-cellular assays | Tyrosinase inhibitory activity (IC50 was 3.3 mg/mL). | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | N/A | [41] |

| Citrus peel extract | 1–50 µg/mL | Melan-a cells | Antioxidant activity DPPH in a dose-dependent manner; Inhibition of tyrosinase activity; Decrease in melanin content in Melan-a in a dose-dependent manner. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Extract antioxidant activity was greater than vitamin C (control), at the same dosage; Melanogenesis inhibition through suppression of melanosome transport in melanocytes | [45] |

| C. unshiu peel-press cakes ethanolic extract | 86 mg/g | B16F10 cells HaCaT cells | No cytotoxic effect on both cell types; Decrease in cellular melanin content and tyrosinase activity in a dose-dependent manner. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Reduction in α-MSH-stimulated tyrosinase, MTIF protein, TRP-1 and TRP-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner | [66] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.1–500 μM | B16F10 cells Neonatal Human Melanocytes | No cytotoxic effect up to 40 μM, on both cell types; Reduction in melanin content and tyrosinase activity, in a dose-dependent manner; Radical scavenging activity against DPPH. | N/A | Cosmetics/ Cosmeceuticals | Decrease in tyrosinase, TRP-1 and TRP-2 proteins in a dose-dependent manner; Suppression of melanogenesis through MTIF downregulation and activation of Erk pathways | [81] |

| Hesperidin/ Extract Type | Hesperidin Levels Tested | Testing Model | Main Biological Properties | Formulation | Potential Applications | Bioavailability/Molecular Pathways/Other Relevant Properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial hesperidin | 1–10% (w/v) | 3T3 cells Wistar rats S. aureus P. aeruginosa | Hemocompatible; Antimicrobial; Cell proliferation and collagen synthesis increase in a dose-dependent manner; In vivo enhanced performance of would therapy in a dose-dependent manner; Granulation tissue and epidermal proliferation; Wound contraction, epidermal layer formation and remodeling | Alginate/Chitosan/ Hesperidin Hydrogel: 2:1 (v/v) alginate and chitosan solutions (sodium alginate (2% (w/v)) in deionized water; chitosan (2% (w/v)) in 0.5% (v/v) acetic acid) + hesperidin (1 or 10% weight of polymer Alg/Chit) + calcium chloride 50 mM (CaCl2) and 10 μL glutaraldehyde with NaOH 1 M (crosslink). | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Neovascularization enhancement in a dose-dependent manner; between 8.9 and 17.2% of hesperidin has been released within the first 3 to 6 h, followed by a sustained release of 77.03 ± 8.71%, over 14 days | [95] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 10 mg/mL | Ex vivo goat skin Wistar albino rats | Improvement of therapeutical treatment for anti-inflammatory activity; The gels were close to a neutral pH (6.8), presenting a low risk of skin irritation | Optimal emulsion formulation: 100 mg stearic acid; 50 mg cholesterol, 125 mg soya lecithin; 100 mg hesperidin in 10 mL ethanol. Optimal topical nanoemulgel: Ratio 1:1 of Carbopol to hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose. | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Potential as a carrier for topical drug delivery system; the hesperidin release from the optimal emulsion was 98.6% after 6 h; regarding ex vivo permeation studies of hesperidin nanoemulgel, the cumulative drug that permeated through the skin was 98.9% after 4 h | [101] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 25–100 µg/mL 1 | Ex vivo rat skin | Hemocompatible; Acceleration of wound closure in a dose-dependent manner; Reduction in inflammation and infection; Improvement of wound contraction, epidermal layer formation, remodeling, and collagen synthesis, in a dose-dependent manner | Hesperidin-loaded PAMAM Dendrimer (Hsp-PAMAM): hesperidin at 2.5, 5, 7.5, or 10% (w/v) was loaded into PAMAM dendrimer. Hsp-PAMAM based hydrogel bandages: sodium alginate; deionized water; chitosan solution and acetic acid. | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Safe and compatible for topical delivery; hesperidin shows an outburst pattern in the first 5 h, followed by delayed release, from the bandages; after 24 h, 86.367% of hesperidin was released; rat skin showed a deposition of the drug in the epidermis up to 15–25 µm; the drug was conserved in between the epidermis and dermis, which is ideal for full-thickness wound therapy | [102] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 5% (w/v) | Swiss albino mice | Wound-healing acceleration; Enhancement of wound contraction; Induction of cell proliferation | Hydrogel: hesperidin (5 g); deionized water (10 mL) and polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG) (380–420 g/mol). | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Increased nitric oxide, glutathione and SOD levels; repression of NF-kB and COX-2 | [103] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.5% (w/w) | Dermal fibroblasts from donated human skin | Fibroblasts proliferation induction; Migration without terminal differentiation and collagen synthesis; Increased progression of wound confluence and closure | Niacinamide (3.0% w/w), L-carnosine (1.0% w/w), hesperidin (0.5% w/w) and Biofactor HSP® (0.05% w/w). | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | N/A | [104] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 30–120 mM | S. aureus E. coli HUVECs cells Sprague–Dawley rats | Antibacterial; DPPH scavenging activity; No significant cytotoxicity; Cell proliferation and migration activity improvement; Acceleration of wound closure after infection by S. aureus; Re-epithelization enhancement; Stimulation of collagen synthesis and deposition; Stimulation of angiogenesis and hair follicle synthesis | Nanoparticles: silver nitrate (AgNO3) (2 mL, 3.397 mg/mL) and hesperidin solution (10 mL, 17.6 mg/mL). Note: The nanoparticles were Incorporated into a hydrogel. | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Activation of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and Stirt 1 expression; suppression of the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (NF-ƙB, MMP9, TNF-α, and IL-6) | [105] |

| Commercial hesperidin | Formulation’s oral intake: 50 mg/kg/day | Sprague–Dawley rats | Necrosis reduction in epidermis and dermis; No congestion or hemorrhage, after 14 days | Oral intake: Bacitracin combined with hesperidin. | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Decrease in IL-1 beta and TNF-α levels | [106] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 0.5% (w/w) | Sprague–Dawley rats | Reduction in wound surface area; Increased wound contraction; Potentiation of wound epithelization by the 28th day; Promotion of cellular infiltration and proliferation | Scaffold: collagen in 0.05-M acetic acid (0.6% (w/w)), chondroitin-6-sulfate (in 0.05-macetic acid). Scaffolds in cosmeceutical formulation: niacinamide (3.0% w/w), L-carnosine (1.0% w/w), hesperidin (0.5% w/w) and Biofactor HSP®(0.05% w/w). Scaffolds crosslinking: 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethyl aminopropyl)-carbodiimide and N-hydroxysuccinimide (EDAC/NHS) and 0.5% glutaraldehyde (GA). | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | N/A | [107] |

| Commercial hesperidin | Oral intake: 25–100 mg/kg/day | Sprague–Dawley rats | Wound half-closure time improvement in a dose-dependent manner; Oxido-nitrosative stress reduction; Hydroxyproline levels (collagen synthesis marker) increase; Angiogenesis and re-epithelization induction | N/A | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | VEGF-c, Ang-1, Tie-2, TGF-β and Smad 2/3 mRNA expression upregulation | [108,109] |

| Commercial hesperidin | Oral intake: 10–80 mg/kg/day | Rats | Wound healing promoted in Diabetes-induced animals; Wound half-closure time improvement | N/A | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | Reduction in MDA, MPO, TNF-α, and IL-6 levels in a dose-dependent manner; stimulation of VEGF, GSH, HDP, and SOD expression in a dose-dependent manner | [110] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 5–10% (w/w) | Swiss albino mice | Epithelization time reduction; Enhancement of wound contraction; Wound-healing activity improved in a dose-dependent manner in the S.aureus infected wound model (antibacterial activity) | Ointments containing: 5% (w/w) or 10% (w/w) hesperidin. | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | N/A | [111] |

| Commercial hesperidin | 50–250 µg/mL 2 | In vitro non-cellular assays | Strong DPPH scavenging activity | Nanoparticles optimal formulation: hesperidin (15 mg); chitosan (20 mg); soya lecithin (10 mg) and surfactant (1 mL) | Skincare Pharmaceutical/ Therapeutic Agent | In vitro, hesperidin presents an outburst pattern in the first 4 h followed by delayed release from nanoparticles; the optimal formulation was stable, safe to use and could improve the topical bioavailability of hesperidin due to its nano-size with a larger surface area; the formulation is a suitable hesperidin delivery agent, leading to improved wound healing | [112] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, C.V.; Pintado, M. Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031890

Rodrigues CV, Pintado M. Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(3):1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031890

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Cristina V., and Manuela Pintado. 2024. "Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 3: 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031890

APA StyleRodrigues, C. V., & Pintado, M. (2024). Hesperidin from Orange Peel as a Promising Skincare Bioactive: An Overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(3), 1890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25031890