Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cancer

3. ROS

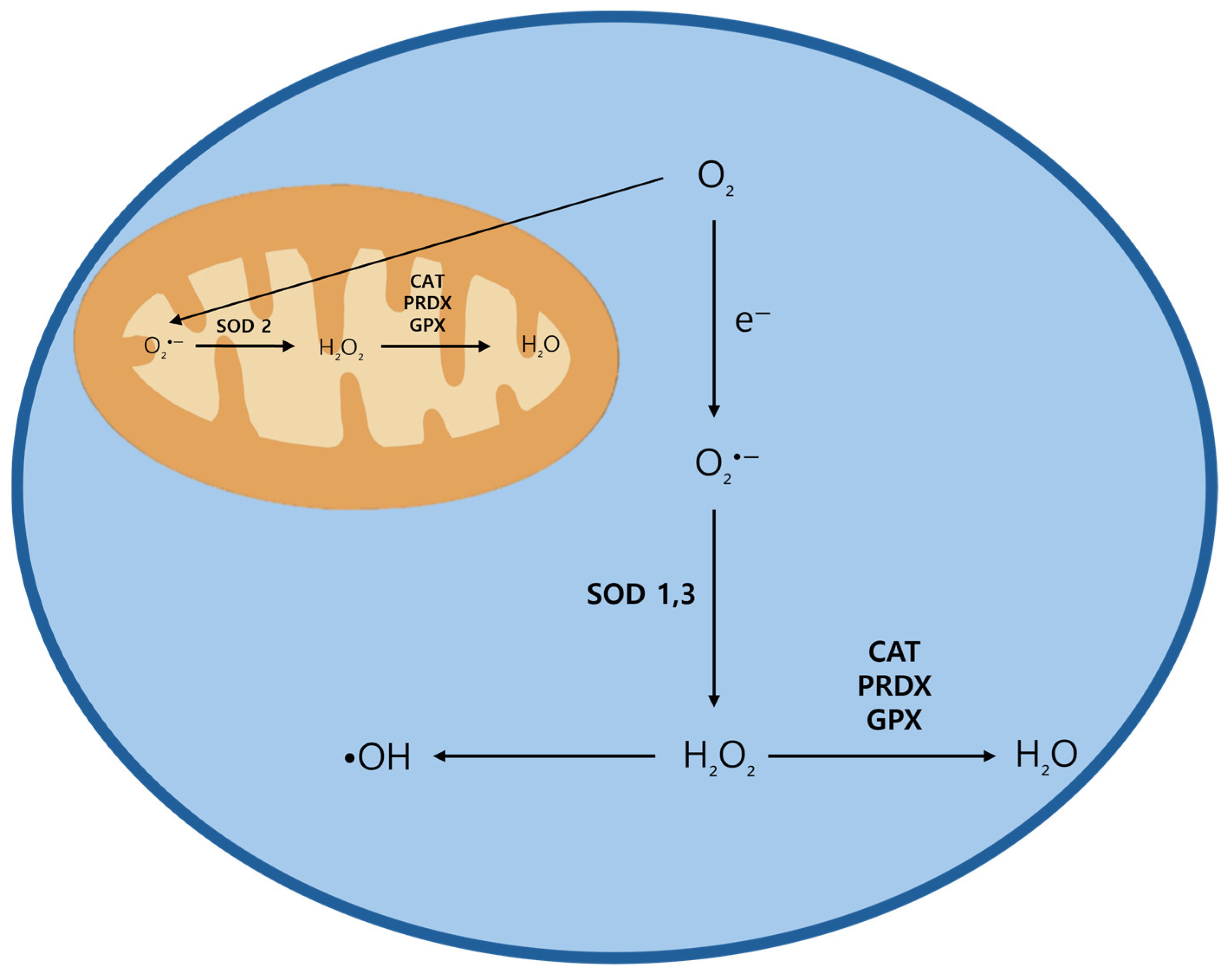

3.1. ROS Generation, Types, and Regulation

| ROS | Role in Cancer | References |

|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (O2−) | Promotes tumor growth and metastasis by enhancing cell proliferation and migration. Can induce cell death at high levels. | [22,23] |

| Hydroxyl radical (•OH) | Causes severe DNA damage and mutations, promoting cancer progression. Excessive levels can trigger apoptosis, killing cancer cells. | [24,25,26] |

| Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) | It functions as a signaling molecule that supports the survival of cancer cells. However, at elevated concentrations, it causes oxidative stress, resulting in cell death. | [26,27] |

| Peroxynitrite (ONOO−) | Facilitates tumor angiogenesis and inflammation. However, excessive oxidative stress can damage cancer cells and suppress tumor growth. | [28,29] |

| Nitric oxide (NO) | Low levels promote cancer growth, while high levels trigger apoptosis and inhibit tumor development. | [30] |

3.2. Interaction Between ROS and Macromolecules

3.3. Signaling Associated with ROS

3.3.1. NRF2

3.3.2. NF-κB

3.3.3. PI3K/AKT

3.3.4. MAPK

4. Cell Death Pathways Related to ROS

4.1. Ferroptosis

4.2. ER Stress

4.3. Apoptosis

4.4. p53 and ROS-Induced Cell Death

4.5. Copper

4.6. Autophagy

4.6.1. Selective Autophagy

Mitophagy

Pexophagy

Aggrephagy

Reticulophagy

Xenophagy

5. Cancer and ROS

5.1. Cancer Cell Survival, Growth

5.2. ROS in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

5.3. ROS in EMT

5.4. Cancer Treatment Using ROS

6. Conclusions and Further Direction

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Chen, H.; Liang, J.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Luo, C.; Tang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Dual Role of Reactive Oxygen Species and their Application in Cancer Therapy. J. Cancer 2021, 12, 5543–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taniyama, Y.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive oxygen species in the vasculature: Molecular and cellular mechanisms. Hypertension 2003, 42, 1075–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Takada, K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberti, M.V.; Locasale, J.W. The Warburg Effect: How Does it Benefit Cancer Cells? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pliszka, M.; Szablewski, L. Glucose Transporters as a Target for Anticancer Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. Energy metabolism of cancer: Glycolysis versus oxidative phosphorylation (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 1151–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukey, M.J.; Wilson, K.F.; Cerione, R.A. Therapeutic strategies impacting cancer cell glutamine metabolism. Future Med. Chem. 2013, 5, 1685–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.C.; Hay, N. The pentose phosphate pathway and cancer. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2014, 39, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Rui, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Mitochondria transcription and cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, L.M.; Yeung, S.C.; Lee, M.H. Cancer metabolic reprogramming: Importance, main features, and potentials for precise targeted anti-cancer therapies. Cancer Biol. Med. 2014, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayyan, M.; Hashim, M.A.; AlNashef, I.M. Superoxide Ion: Generation and Chemical Implications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 3029–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galadari, S.; Rahman, A.; Pallichankandy, S.; Thayyullathil, F. Reactive oxygen species and cancer paradox: To promote or to suppress? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 104, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedard, K.; Krause, K.H. The NOX family of ROS-generating NADPH oxidases: Physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 245–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecarini, V.; Gee, J.; Fioretti, E.; Amici, M.; Angeletti, M.; Eleuteri, A.M.; Keller, J.N. Protein oxidation and cellular homeostasis: Emphasis on metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1773, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, E.C.; Vousden, K.H. The role of ROS in tumour development and progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkovic, L.; Cipak Gasparovic, A.; Cindric, M.; Mouthuy, P.A.; Zarkovic, N. Short Overview of ROS as Cell Function Regulators and Their Implications in Therapy Concepts. Cells 2019, 8, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porporato, P.E.; Payen, V.L.; Pérez-Escuredo, J.; De Saedeleer, C.J.; Danhier, P.; Copetti, T.; Dhup, S.; Tardy, M.; Vazeille, T.; Bouzin, C.; et al. A Mitochondrial Switch Promotes Tumor Metastasis. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hileman, E.A.; Achanta, G.; Huang, P. Superoxide dismutase: An emerging target for cancer therapeutics. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2001, 5, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryston, T.B.; Georgiev, A.B.; Pissis, P.; Georgakilas, A.G. Role of oxidative stress and DNA damage in human carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011, 711, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olinski, R.; Gackowski, D.; Rozalski, R.; Foksinski, M.; Bialkowski, K. Oxidative DNA damage in cancer patients: A cause or a consequence of the disease development? Mutat. Res./Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2003, 531, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ye, X.; Xiong, Z.; Ihsan, A.; Ares, I.; Martínez, M.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.-R.; Anadón, A.; Wang, X.; et al. Cancer Metabolism: The Role of ROS in DNA Damage and Induction of Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Metabolites 2023, 13, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, G.; Quiney, C.; Cotter, T.G. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2655–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, D.H.; Bartoli, M.; El-Remessy, A.B.; Al-Shabrawey, M.; Lemtalsi, T.; Fulton, D.; Caldwell, R.B. Peroxynitrite increases VEGF expression in vascular endothelial cells via STAT3. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 39, 1353–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Deng, Z.; Lei, C.; Ding, X.; Li, J.; Wang, C. The Role of Oxidative Stress in Tumorigenesis and Progression. Cells 2024, 13, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.H.; Dervan, E.; Bhattacharyya, D.D.; McAuliffe, J.D.; Miranda, K.M.; Glynn, S.A. The Role of Nitric Oxide in Cancer: Master Regulator or NOt? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, B. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant vitamins: Mechanisms of action. Am. J. Med. 1994, 97 (Suppl. 1), S5–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadyro, O.; Lisovskaya, A. ROS-induced lipid transformations without oxygen participation. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2019, 221, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endale, H.T.; Tesfaye, W.; Mengstie, T.A. ROS induced lipid peroxidation and their role in ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1226044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volinsky, R.; Kinnunen, P.K. Oxidized phosphatidylcholines in membrane-level cellular signaling: From biophysics to physiology and molecular pathology. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2806–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzino, G.; Irrera, N.; Cucinotta, M.; Pallio, G.; Mannino, F.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 8416763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The Chemistry of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Revisited: Outlining Their Role in Biological Macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and Induced Pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Rhodes, C.J.; Moncol, J.; Izakovic, M.; Mazur, M. Free radicals, metals and antioxidants in oxidative stress-induced cancer. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2006, 160, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, M.; Jiang, L.; Akatsuka, S.; Suyama, M.; Toyokuni, S. Genome-wide profiling of 8-oxoguanine reveals its association with spatial positioning in nucleus. DNA Res. 2014, 21, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H.; Crain, P.F.; Kuchino, Y.; Nishimura, S.; Ootsuyama, A.; Tanooka, H. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine moiety in cellular DNA by agents producing oxygen radicals and evidence for its repair. Carcinogenesis 1986, 7, 1849–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, P.C.; Gillespie, J.W.; Charboneau, L.; Bichsel, V.E.; Paweletz, C.P.; Calvert, V.S.; Kohn, E.C.; Emmert-Buck, M.R.; Liotta, L.A.; Petricoin, E.F., 3rd. Mitochondrial proteome: Altered cytochrome c oxidase subunit levels in prostate cancer. Proteomics 2003, 3, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrella, P.; Xiao, Y.; Fliss, M.; Sanchez-Cespedes, M.; Mazzarelli, P.; Rinaldi, M.; Nicol, T.; Gabrielson, E.; Cuomo, C.; Cohen, D.; et al. Detection of mitochondrial DNA mutations in primary breast cancer and fine-needle aspirates. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 7623–7626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Z.; Gokden, N.; Greene, G.F.; Mukunyadzi, P.; Kadlubar, F.F. Extensive somatic mitochondrial mutations in primary prostate cancer using laser capture microdissection. Cancer Res. 2002, 62, 6470–6474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Ortega, M.; Carrera, A.C.; Garrido, A. Role of NRF2 in Lung Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Jia, Z.; Trush, M.A.; Li, Y.R. Nrf2 Deficiency Promotes Melanoma Growth and Lung Metastasis. React. Oxyg. Species (Apex) 2016, 2, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hammad, A.; Zheng, Z.H.; Gao, Y.; Namani, A.; Shi, H.F.; Tang, X. Identification of novel Nrf2 target genes as prognostic biomarkers in colitis-associated colorectal cancer in Nrf2-deficient mice. Life Sci. 2019, 238, 116968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegon, S.; Columbano, A.; Giordano, S. The Dual Roles of NRF2 in Cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2016, 22, 578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, H.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Hayes, J.D. NRF2 and the Ambiguous Consequences of Its Activation during Initiation and the Subsequent Stages of Tumourigenesis. Cancers 2020, 12, 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.H.; Gong, P.; Hu, B.; Stewart, D.; Choi, M.E.; Choi, A.M.; Alam, J. Identification of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) as an Nrf2-interacting protein. Implication for heme oxygenase-1 gene regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 20858–20865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivinski, J.; Zhang, D.D.; Chapman, E. Targeting NRF2 to treat cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, H.; Motohashi, H. NRF2 addiction in cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2018, 109, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlein, L.J.; Thamm, D.H. Review: NF-kB activation in canine cancer. Vet. Pathol. 2022, 59, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingappan, K. NF-κB in Oxidative Stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, I.; Ghosh, S. Use of cell permeable NBD peptides for suppression of inflammation. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006, 65 (Suppl. 3), iii75–iii82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchis-Ordoñez, A.; Ramírez-Ramírez, D.; Pelayo, R. The triad inflammation-microenvironment-tumor initiating cells in leukemia progression. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2021, 19, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Shen, S.; Verma, I.M. NF-κB, an active player in human cancers. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Acquisto, F.; de Cristofaro, F.; Maiuri, M.C.; Tajana, G.; Carnuccio, R. Protective role of nuclear factor kappa B against nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in J774 macrophages. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karin, M.; Cao, Y.; Greten, F.R.; Li, Z.W. NF-kappaB in cancer: From innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, B.B. Nuclear factor-κB: The enemy within. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Robinson, J.B.; Deguzman, A.; Bucana, C.D.; Fidler, I.J. Blockade of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenicity of human ovarian cancer cells by suppressing expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin 8. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5334–5339. [Google Scholar]

- Bajaj, S.; Kumar, M.S.; Peters, G.; Mayur, Y. Targeting telomerase for its advent in cancer therapeutics. Med. Res. Rev. 2020, 40, 1871–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medunjanin, S.; Schleithoff, L.; Fiegehenn, C.; Weinert, S.; Zuschratter, W.; Braun-Dullaeus, R.C. GSK-3β controls NF-kappaB activity via IKKγ/NEMO. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Götschel, F.; Kern, C.; Lang, S.; Sparna, T.; Markmann, C.; Schwager, J.; McNelly, S.; von Weizsäcker, F.; Laufer, S.; Hecht, A.; et al. Inhibition of GSK3 differentially modulates NF-kappaB, CREB, AP-1 and beta-catenin signaling in hepatocytes, but fails to promote TNF-alpha-induced apoptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghantous, A.; Sinjab, A.; Herceg, Z.; Darwiche, N. Parthenolide: From plant shoots to cancer roots. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18, 894–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, F.; Shafiee, M.; Banikazemi, Z.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Khanbabaei, H.; Shamshirian, A.; Amiri Moghadam, S.; ArefNezhad, R.; Sahebkar, A.; Avan, A.; et al. Curcumin inhibits NF-kB and Wnt/β-catenin pathways in cervical cancer cells. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Konno, S.; Ozaki, M.; Umezawa, K.; Yamashita, K.; Todo, S.; Nishimura, M. Dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ), a novel NF-kappaB inhibitor, inhibits allergic inflammation and airway remodelling in murine models of asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2012, 42, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taromi, S.; Lewens, F.; Arsenic, R.; Sedding, D.; Sänger, J.; Kunze, A.; Möbs, M.; Benecke, J.; Freitag, H.; Christen, F.; et al. Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib enhances the effect of standard chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 97061–97078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcet, X.; Llobet, D.; Pallares, J.; Matias-Guiu, X. NF-kB in development and progression of human cancer. Virchows Archiv 2005, 446, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Sun, M.M.; Zhang, G.G.; Yang, J.; Chen, K.S.; Xu, W.W.; Li, B. Targeting PI3K/Akt signal transduction for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 2021, 6, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Guillermet-Guibert, J.; Graupera, M.; Bilanges, B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ullah, R.; Tong, J.; Shen, Y. The role of the PI3K/AKT signalling pathway in the corneal epithelium: Recent updates. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, L.M.; Yuzugullu, H.; Zhao, J.J. PI3K in cancer: Divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanker, A.B.; Kaklamani, V.; Arteaga, C.L. Challenges for the Clinical Development of PI3K Inhibitors: Strategies to Improve Their Impact in Solid Tumors. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Mei, W.; Zeng, C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Therapeutics: Are We Making Headway? Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 819128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, M.; Anzeneder, T.; Schulz, A.; Beckmann, G.; Byrne, A.T.; Jeffers, M.; Pena, C.; Politz, O.; Köchert, K.; Vonk, R.; et al. AKT1 (E17K) mutation profiling in breast cancer: Prevalence, concurrent oncogenic alterations, and blood-based detection. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Horta, S.; Mateus, R.; Videira, M.A. Implications of Akt2/Twist crosstalk on breast cancer metastatic outcome. Drug Discov. Today 2015, 20, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, A.; Benayed, R.; Shah, R.H.; Syed, A.; Middha, S.; Kim, H.R.; Srinivasan, P.; Gao, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Devlin, S.M.; et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, D.R.; Wu, Y.M.; Lonigro, R.J.; Vats, P.; Cobain, E.; Everett, J.; Cao, X.; Rabban, E.; Kumar-Sinha, C.; Raymond, V.; et al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature 2017, 548, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, N.V.; Jücker, M. The Role of mTOR Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoki, K.; Li, Y.; Zhu, T.; Wu, J.; Guan, K.L. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Embi, N.; Rylatt, D.B.; Cohen, P. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 from rabbit skeletal muscle. Separation from cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylase kinase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1980, 107, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda, P.; Akula, S.M.; Abrams, S.L.; Steelman, L.S.; Martelli, A.M.; Cocco, L.; Ratti, S.; Candido, S.; Libra, M.; Montalto, G.; et al. Targeting GSK3 and Associated Signaling Pathways Involved in Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beurel, E.; Grieco, S.F.; Jope, R.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): Regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 148, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Herreros-Villanueva, M.; Koenig, A.; Deng, Z.; de Narvajas, A.A.; Gomez, T.S.; Meng, X.; Bujanda, L.; Ellenrieder, V.; Li, X.K.; et al. Differential activity of GSK-3 isoforms regulates NF-κB and TRAIL- or TNFα induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ougolkov, A.V.; Billadeau, D.D. Targeting GSK-3: A promising approach for cancer therapy? Future Oncol. 2006, 2, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbreth, M.; Aschner, M. GSK-3β, a double-edged sword in Nrf2 regulation: Implications for neurological dysfunction and disease. F1000Res 2018, 7, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leis, H.; Segrelles, C.; Ruiz, S.; Santos, M.; Paramio, J.M. Expression, localization, and activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta during mouse skin tumorigenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 2002, 35, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Cheong, Y.K.; Kim, N.H.; Chung, H.T.; Kang, D.G.; Pae, H.O. Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases and Reactive Oxygen Species: How Can ROS Activate MAPK Pathways? J. Signal Transduct. 2011, 2011, 792639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Boiti, A.; Vallone, D.; Foulkes, N.S. Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling and Oxidative Stress: Transcriptional Regulation and Evolution. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarpia, L.; Lippman, S.M.; El-Naggar, A.K. Targeting the MAPK-RAS-RAF signaling pathway in cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2012, 16, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Medarde, A.; Santos, E. Ras in cancer and developmental diseases. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, M.J.; Marais, R. Guilty as charged: B-RAF is a human oncogene. Cancer Cell 2004, 6, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Targeting oncogenic Raf protein-serine/threonine kinases in human cancers. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 135, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.J.; Kwon, J.H.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, J.W.; Yang, Y.C. Increased MAPK activity and MKP-1 overexpression in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 250, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, W.Z.; Liu, T.; Feng, X.; Yang, N.; Zhou, H.F. Signaling pathway of MAPK/ERK in cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, senescence and apoptosis. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2015, 35, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pua, L.J.W.; Mai, C.W.; Chung, F.F.; Khoo, A.S.; Leong, C.O.; Lim, W.M.; Hii, L.W. Functional Roles of JNK and p38 MAPK Signaling in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, R.; Chatterjee, J. ROS and oncogenesis with special reference to EMT and stemness. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2020, 99, 151073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maik-Rachline, G.; Hacohen-Lev-Ran, A.; Seger, R. Nuclear ERK: Mechanism of Translocation, Substrates, and Role in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Bi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Qin, F.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. Targeting RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway in human cancer: Current status in clinical trials. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Luo, R.; Liang, X.; Wu, Q.; Gong, C. Recent advances in enhancing reactive oxygen species based chemodynamic therapy. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 2213–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannia, B.; Vandenabeele, P.; Vanden Berghe, T. Targeting Ferroptosis to Iron Out Cancer. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 830–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torti, S.V.; Manz, D.H.; Paul, B.T.; Blanchette-Farra, N.; Torti, F.M. Iron and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 38, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, P.; Bai, T.; Sun, Y. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relations With Regulated Cell Death: A Review. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Maiorino, M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1830, 3289–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Kim, K.J.; Gaschler, M.M.; Patel, M.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4966–E4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Yu, T.; Zhu, R.; Lu, J.; Ouyang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Cui, J.; Jiang, F.; et al. Timosaponin AIII promotes non-small-cell lung cancer ferroptosis through targeting and facilitating HSP90 mediated GPX4 ubiquitination and degradation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 1471–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, B.; Yang, S.; Huang, J. IRF1 suppresses colon cancer proliferation by reducing SPI1-mediated transcriptional activation of GPX4 and promoting ferroptosis. Exp. Cell Res. 2023, 431, 113733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Schneider, M.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Hammond, V.J.; Herbach, N.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; Eggenhofer, E.; et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.H.; Shimoni, Y.; Yang, W.S.; Subramaniam, P.; Iyer, A.; Nicoletti, P.; Rodríguez Martínez, M.; López, G.; Mattioli, M.; Realubit, R.; et al. Elucidating Compound Mechanism of Action by Network Perturbation Analysis. Cell 2015, 162, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, K.; Skouta, R.; Kaplan, A.; Yang, W.S.; Hayano, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Brown, L.M.; Valenzuela, C.A.; Wolpaw, A.J.; Stockwell, B.R. Global survey of cell death mechanisms reveals metabolic regulation of ferroptosis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrams, R.P.; Carroll, W.L.; Woerpel, K.A. Five-Membered Ring Peroxide Selectively Initiates Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, F.; Wang, T.; Jiao, Y. The Role of Erastin in Ferroptosis and Its Prospects in Cancer Therapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 5429–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Kroemer, G.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 66, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.R.; Thorburn, A. Autophagy and organelle homeostasis in cancer. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, M.R.; Nissar, U.A.; Afnan, Q.; Rafiq, R.A.; Sharma, L.; Amin, S.; Kaiser, P.; Sharma, P.R.; Tasduq, S.A. Oxidative stress mediated Ca(2+) release manifests endoplasmic reticulum stress leading to unfolded protein response in UV-B irradiated human skin cells. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 75, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheva, V.I.; Domingos, P.M. Cellular responses to endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Apoptosis 2009, 14, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Lee, J.; Ha, J.; Kang, I.; Choe, W. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Its Impact on Adipogenesis: Molecular Mechanisms Implicated. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, R.; Reed, J.C. ER stress-induced cell death mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1833, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosskreutz, J.; Van Den Bosch, L.; Keller, B.U. Calcium dysregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Cell Calcium 2010, 47, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Tian, M.; Ding, C.; Yu, S. The C/EBP Homologous Protein (CHOP) Transcription Factor Functions in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Apoptosis and Microbial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, B. Anti-Cancer Natural Products and Their Bioactive Compounds Inducing ER Stress-Mediated Apoptosis: A Review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.M.; Kim, B.M.; Park, J.B. ω-Hydroxyundec-9-enoic acid induces apoptosis through ROS-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 448, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.H.; Hang, L.W.; Yang, J.S.; Chen, H.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Chiang, J.H.; Lu, C.C.; Yang, J.L.; Lai, T.Y.; Ko, Y.C.; et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer NCI-H460 cells through ER stress and caspase cascade- and mitochondria-dependent pathways. Anticancer Res. 2010, 30, 2125–2133. [Google Scholar]

- Hsia, T.C.; Yu, C.C.; Hsu, S.C.; Tang, N.Y.; Lu, H.F.; Huang, Y.P.; Wu, S.H.; Lin, J.G.; Chung, J.G. Cantharidin induces apoptosis of H460 human lung cancer cells through mitochondria-dependent pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, H.U.; Haj-Yehia, A.; Levi-Schaffer, F. Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction. Apoptosis 2000, 5, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ow, Y.-L.P.; Green, D.R.; Hao, Z.; Mak, T.W. Cytochrome c: Functions beyond respiration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orrenius, S.; Gogvadze, V.; Zhivotovsky, B. Calcium and mitochondria in the regulation of cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 460, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L.; Brenner, C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 99–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobrial, I.M.; Witzig, T.E.; Adjei, A.A. Targeting apoptosis pathways in cancer therapy. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005, 55, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Activation of apoptosis signalling pathways by reactive oxygen species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 2977–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Wei, Z.; Yang, W.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J. The role of BCL-2 family proteins in regulating apoptosis and cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 985363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidi, E.; Brunham, L.R. Regulated cell death pathways in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorn, C.F.; Oshiro, C.; Marsh, S.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; McLeod, H.; Klein, T.E.; Altman, R.B. Doxorubicin pathways: Pharmacodynamics and adverse effects. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2011, 21, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, W.P.; Chau, S.P.; Kong, S.K.; Fung, K.P.; Kwok, T.T. Reactive oxygen species mediate doxorubicin induced p53-independent apoptosis. Life Sci. 2003, 73, 2047–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebl, M.C.; Hofmann, T.G. The Role of p53 Signaling in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhlig, L.; Rother, K. One function--multiple mechanisms: The manifold activities of p53 as a transcriptional repressor. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 464916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gu, W. p53 in ferroptosis regulation: The new weapon for the old guardian. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Wang, S.J.; Li, D.; Chu, B.; Gu, W. Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E6806–E6812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Y.; Padanilam, B.J. Regulation of necrotic cell death: p53, PARP1 and cyclophilin D-overlapping pathways of regulated necrosis? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 2309–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, H.C.; Ren, D.; Wang, G.X.; Chen, D.Y.; Westergard, T.D.; Kim, H.; Sasagawa, S.; Hsieh, J.J.; Cheng, E.H. The p53-cathepsin axis cooperates with ROS to activate programmed necrotic death upon DNA damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, L.M.; Libedinsky, A.; Elorza, A.A. Role of Copper on Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 711227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porporato, P.E.; Filigheddu, N.; Pedro, J.M.B.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; Rossen, J.; Joesch-Cohen, L.; Humeidi, R.; Spangler, R.D.; et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, P.; Vidal, C.; Dey, S.; Zhang, L. Mitochondria Targeting as an Effective Strategy for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, M.; Vo, N.H.; Shin Ogawa, L.; Chimmanamada, D.; Inoue, T.; Chu, J.; Beaudette-Zlatanova, B.C.; Lu, R.; Blackman, R.K.; Barsoum, J.; et al. The oncology drug elesclomol selectively transports copper to the mitochondria to induce oxidative stress in cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 52, 2142–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshner, J.R.; He, S.; Balasubramanyam, V.; Kepros, J.; Yang, C.Y.; Zhang, M.; Du, Z.; Barsoum, J.; Bertin, J. Elesclomol induces cancer cell apoptosis through oxidative stress. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 2319–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, D.; Zhao, L.; Shi, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, Z. Copper in cancer: From pathogenesis to therapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Detappe, A.; Cai, K.; Keys, H.R.; Brune, Z.; Ying, W.; Thiru, P.; Reidy, M.; Kugener, G.; Rossen, J.; et al. Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019, 15, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filomeni, G.; De Zio, D.; Cecconi, F. Oxidative stress and autophagy: The clash between damage and metabolic needs. Cell Death Differ. 2015, 22, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Han, S.; Kim, S.; Kang, I. Targeting Lipid Metabolism in Cancer Stem Cells for Anticancer Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denton, D.; Kumar, S. Autophagy-dependent cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, R.C.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, H.; Park, H.W.; Chang, Y.Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Neufeld, T.P.; Dillin, A.; Guan, K.L. ULK1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating Beclin-1 and activating VPS34 lipid kinase. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 15, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.; Klionsky, D.J. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. ‘Protein modifications: Beyond the usual suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Noda, T.; Yoshimori, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Ishii, T.; George, M.D.; Klionsky, D.J.; Ohsumi, M.; Ohsumi, Y. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature 1998, 395, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi, Y. Molecular dissection of autophagy: Two ubiquitin-like systems. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001, 2, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroemer, G.; Mariño, G.; Levine, B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Canadien, V.; Lam, G.Y.; Steinberg, B.E.; Dinauer, M.C.; Magalhaes, M.A.; Glogauer, M.; Grinstein, S.; Brumell, J.H. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 6226–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filomeni, G.; Desideri, E.; Cardaci, S.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Under the ROS…thiol network is the principal suspect for autophagy commitment. Autophagy 2010, 6, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Azad, M.B.; Gibson, S.B. Superoxide is the major reactive oxygen species regulating autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherz-Shouval, R.; Elazar, Z. Regulation of autophagy by ROS: Physiology and pathology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, 36, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redza-Dutordoir, M.; Kassis, S.; Ve, H.; Grondin, M.; Averill-Bates, D.A. Inhibition of autophagy sensitises cells to hydrogen peroxide-induced apoptosis: Protective effect of mild thermotolerance acquired at 40 °C. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 3050–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherz-Shouval, R.; Shvets, E.; Fass, E.; Shorer, H.; Gil, L.; Elazar, Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 1749–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubli, D.A.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Mitochondria and mitophagy: The yin and yang of cell death control. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 1208–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuri, M.C.; Galluzzi, L.; Morselli, E.; Kepp, O.; Malik, S.A.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010, 22, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaminets, A.; Behl, C.; Dikic, I. Ubiquitin-Dependent And Independent Signals In Selective Autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, C.W.; Lee, S.H. The Roles of Autophagy in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, E.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Mariño, G.; Michaud, M.; Vitale, I.; Maiuri, M.C.; Kroemer, G. Oncosuppressive functions of autophagy. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 2011, 14, 2251–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.Y.; Xia, B.; White, E. Autophagy-mediated tumor promotion. Cell 2013, 155, 1216–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, J.; Gammoh, N.; Ryan, K.M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 560–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Lei, P.; Zhang, Q. ROS and Autophagy: Interactions and Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 35, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.A.; Quinsay, M.N.; Orogo, A.M.; Giang, K.; Rikka, S.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3) interacts with Bnip3 protein to selectively remove endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria via autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19094–19104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, I.; Kirkin, V.; McEwan, D.G.; Zhang, J.; Wild, P.; Rozenknop, A.; Rogov, V.; Löhr, F.; Popovic, D.; Occhipinti, A.; et al. Nix is a selective autophagy receptor for mitochondrial clearance. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Feng, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, M.; Zheng, Q.; Song, P.; Ma, Q.; Zhu, C.; Wang, R.; Qi, W.; et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsu, K.; Murakawa, T.; Yamaguchi, O. BCL2L13 is a mammalian homolog of the yeast mitophagy receptor Atg32. Autophagy 2015, 11, 1932–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujabal, Z.; Birgisdottir, Å.B.; Sjøttem, E.; Brenne, H.B.; Øvervatn, A.; Habisov, S.; Kirkin, V.; Lamark, T.; Johansen, T. FKBP8 recruits LC3A to mediate Parkin-independent mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 947–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Chiang, W.C.; Sumpter, R., Jr.; Mishra, P.; Levine, B. Prohibitin 2 Is an Inner Mitochondrial Membrane Mitophagy Receptor. Cell 2017, 168, 224–238.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, L.P.; Macleod, K.F. Mitophagy in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 3817–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, L.E.; Springer, M.Z.; Poole, L.P.; Kim, C.J.; Macleod, K.F. Expanding perspectives on the significance of mitophagy in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2017, 47, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lin, M.; Wu, R.; Wang, X.; Yang, B.; Levine, A.J.; Hu, W.; Feng, Z. Parkin, a p53 target gene, mediates the role of p53 in glucose metabolism and the Warburg effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16259–16264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Yue, X.; Wu, H.; Huang, S.; Chen, J.; Tomsky, K.; Xie, H.; Khella, C.A.; et al. Parkin targets HIF-1α for ubiquitination and degradation to inhibit breast tumor progression. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, S.A.; Sideris, D.P.; Giagtzoglou, N.; Ni, L.; Kankel, M.W.; Sen, A.; Bochicchio, L.E.; Huang, C.H.; Nussenzweig, S.C.; Worley, S.H.; et al. PINK1/Parkin Influences Cell Cycle by Sequestering TBK1 at Damaged Mitochondria, Inhibiting Mitosis. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 225–235.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Wang, L.; Tian, Y.; Chan, S.T.; Cho, C.; Machida, K.; Chen, D.; Ou, J.J. Mitophagy Controls the Activities of Tumor Suppressor p53 to Regulate Hepatic Cancer Stem Cells. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 281–292.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodda, D.J.; Chew, J.-L.; Lim, L.-H.; Loh, Y.-H.; Wang, B.; Ng, H.-H.; Robson, P. Transcriptional Regulation of Nanog by OCT4 and SOX2*. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 24731–24737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasefifar, P.; Motafakkerazad, R.; Maleki, L.A.; Najafi, S.; Ghrobaninezhad, F.; Najafzadeh, B.; Alemohammad, H.; Amini, M.; Baghbanzadeh, A.; Baradaran, B. Nanog, as a key cancer stem cell marker in tumor progression. Gene 2022, 827, 146448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koop, E.A.; van Laar, T.; van Wichen, D.F.; de Weger, R.A.; Wall, E.; van Diest, P.J. Expression of BNIP3 in invasive breast cancer: Correlations with the hypoxic response and clinicopathological features. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chourasia, A.H.; Tracy, K.; Frankenberger, C.; Boland, M.L.; Sharifi, M.N.; Drake, L.E.; Sachleben, J.R.; Asara, J.M.; Locasale, J.W.; Karczmar, G.S.; et al. Mitophagy defects arising from BNip3 loss promote mammary tumor progression to metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2015, 16, 1145–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Tian, W.; Hu, Z.; Chen, G.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Xue, P.; Zhou, C.; Liu, L.; et al. ULK1 translocates to mitochondria and phosphorylates FUNDC1 to regulate mitophagy. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, L.; Pei, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Cui, W.; Chen, J. FUN14 domain-containing 1 promotes breast cancer proliferation and migration by activating calcium-NFATC1-BMI1 axis. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, L.; Wu, H.; Wang, T.W.; Yang, N.; Guo, X.; Jang, X.J. Hydrogen peroxide-induced mitophagy contributes to laryngeal cancer cells survival via the upregulation of FUNDC1. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2019, 21, 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islinger, M.; Voelkl, A.; Fahimi, H.D.; Schrader, M. The peroxisome: An update on mysteries 2.0. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 150, 443–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, W. Mechanisms and Functions of Pexophagy in Mammalian Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.N.; Dutta, R.K.; Maharjan, Y.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Lim, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Cho, D.-H.; So, H.-S.; Choe, S.-K.; Park, R. Catalase inhibition induces pexophagy through ROS accumulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tripathi, D.N.; Jing, J.; Alexander, A.; Kim, J.; Powell, R.T.; Dere, R.; Tait-Mulder, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Paull, T.T.; et al. ATM functions at the peroxisome to induce pexophagy in response to ROS. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Subramani, S. Role of PEX5 ubiquitination in maintaining peroxisome dynamics and homeostasis. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 2037–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franovic, A.; Holterman, C.E.; Payette, J.; Lee, S. Human cancers converge at the HIF-2alpha oncogenic axis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21306–21311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, M.D.; Lu, C.; Tutnauer, J.; Hartman, T.E.; Hwang, S.K.; Murphy, C.J.; Pauli, C.; Morris, R.; Taylor, S.; Bosch, K.; et al. High-fructose corn syrup enhances intestinal tumor growth in mice. Science 2019, 363, 1345–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, R.; Lisec, J.; Swinnen, J.V.; Zaidi, N. Lipid metabolism in cancer cells under metabolic stress. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Saarinen, A.M.; Hitosugi, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Ho, T.H.; Liu, J. Inhibition of intracellular lipolysis promotes human cancer cell adaptation to hypoxia. eLife 2017, 6, e31132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazumder, S.; Higgins, P.J.; Samarakoon, R. Downstream Targets of VHL/HIF-α Signaling in Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma Progression: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Relevance. Cancers 2023, 15, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lévy, E.; El Banna, N.; Baïlle, D.; Heneman-Masurel, A.; Truchet, S.; Rezaei, H.; Huang, M.E.; Béringue, V.; Martin, D.; Vernis, L. Causative Links between Protein Aggregation and Oxidative Stress: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipp, M.S.; Kasturi, P.; Hartl, F.U. The proteostasis network and its decline in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Chi, H.; Gou, S.; Guo, X.; Li, L.; Peng, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Nian, S.; Yuan, Q. An Aggrephagy-Related LncRNA Signature for the Prognosis of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Genes 2023, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, B.; Martens, S.; Ferrari, L. Aggrephagy at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2023, 136, jcs260888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, D.; Suzuki, T.; Mitsuishi, Y.; Miki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Sugawara, S.; Watanabe, M.; Sakurada, A.; Endo, C.; Uruno, A.; et al. Accumulation of p62/SQSTM1 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda-Troncoso, C.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Burgos, P.V. Pro-Tumoral Functions of Autophagy Receptors in the Modulation of Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 619727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Xiong, Z.; Yuan, C.; Bao, L.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Li, W.; Tong, J.; Qu, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Low neighbor of Brca1 gene expression predicts poor clinical outcome and resistance of sunitinib in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 94819–94833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janiszewska, M.; Primi, M.C.; Izard, T. Cell adhesion in cancer: Beyond the migration of single cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 2495–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, M.; Hoshino, D.; Koshikawa, N.; Akizawa, T.; Seiki, M. Turnover of focal adhesions and cancer cell migration. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 310616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenific, C.M.; Stehbens, S.J.; Goldsmith, J.; Leidal, A.M.; Faure, N.; Ye, J.; Wittmann, T.; Debnath, J. NBR1 enables autophagy-dependent focal adhesion turnover. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Venida, A.; Yano, J.; Biancur, D.E.; Kakiuchi, M.; Gupta, S.; Sohn, A.S.W.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Lin, E.Y.; Parker, S.J.; et al. Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I. Nature 2020, 581, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perincheri, S. Tumor Microenvironment of Lymphomas and Plasma Cell Neoplasms: Broad Overview and Impact on Evaluation for Immune Based Therapies. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 719140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Xu, S.; Jiang, F.; Han, Y.; Chen, F.; Liu, Z. Aggrephagy-related patterns in tumor microenvironment, prognosis, and immunotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia: A comprehensive single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1195392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Tan, J.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, Q. Crosstalk of ER stress-mediated autophagy and ER-phagy: Involvement of UPR and the core autophagy machinery. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 3867–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephani, M.; Picchianti, L.; Gajic, A.; Beveridge, R.; Skarwan, E.; Sanchez de Medina Hernandez, V.; Mohseni, A.; Clavel, M.; Zeng, Y.; Naumann, C.; et al. A cross-kingdom conserved ER-phagy receptor maintains endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis during stress. eLife 2020, 9, jcs260888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.K.; Chui, C.H.; Fatima, S.; Kok, S.H.; Pak, K.C.; Ou, T.M.; Hui, K.S.; Wong, M.M.; Wong, J.; Law, S.; et al. Oncogenic properties of a novel gene JK-1 located in chromosome 5p and its overexpression in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 19, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasem, K.; Gopalan, V.; Salajegheh, A.; Lu, C.T.; Smith, R.A.; Lam, A.K. The roles of JK-1 (FAM134B) expressions in colorectal cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 326, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, R.; Li, S.; Li, G.; Lu, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Lei, J.; Ma, L.; Ke, W.; Liao, Z.; et al. FAM134B-Mediated ER-phagy Upregulation Attenuates AGEs-Induced Apoptosis and Senescence in Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 3843145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kaufman, R.J. The impact of the endoplasmic reticulum protein-folding environment on cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Sheng, M.; Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, S.; Du, H. Berberine protects steatotic donor undergoing liver transplantation via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated reticulophagy. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2019, 244, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammanathan, V.; Vats, S.; Abraham, I.M.; Manjithaya, R. Xenophagy in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2020, 66, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiramel, A.I.; Brady, N.R.; Bartenschlager, R. Divergent Roles of Autophagy in Virus Infection. Cells 2013, 2, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudchodkar, S.B.; Levine, B. Viruses and autophagy. Rev. Med. Virol. 2009, 19, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, X.; Liang, X.; Chen, L.; Guo, C.; Han, W.; Pan, H.; Li, X. Bacterial xenophagy and its possible role in cancer: A potential antimicrobial strategy for cancer prevention and treatment. Autophagy 2017, 13, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Lin, S.T.; Liu, J.J.; Chang, W.W.; Hsieh, J.L.; Wang, W.K. Salmonella induce autophagy in melanoma by the downregulation of AKT/mTOR pathway. Gene Ther. 2014, 21, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera, G. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation products in cancer progression and therapy. ISRN Oncol. 2012, 2012, 137289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieborowska-Skorska, M.; Kopinski, P.K.; Ray, R.; Hoser, G.; Ngaba, D.; Flis, S.; Cramer, K.; Reddy, M.M.; Koptyra, M.; Penserga, T.; et al. Rac2-MRC-cIII-generated ROS cause genomic instability in chronic myeloid leukemia stem cells and primitive progenitors. Blood 2012, 119, 4253–4263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moloney, J.N.; Cotter, T.G. ROS signalling in the biology of cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 80, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. HIF-1 and tumor progression: Pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol. Med. 2002, 8 (Suppl. 4), S62–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, M.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Kim, W.; Valiando, J.; Ohh, M.; Salic, A.; Asara, J.M.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: Implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovale, L.; Singh, M.K.; Kim, J.; Ha, J. Role of Autophagy and AMPK in Cancer Stem Cells: Therapeutic Opportunities and Obstacles in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.Y.; Storz, P. Reactive oxygen species in cancer. Free Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Tang, Y.Q.; Miao, H. Metabolism in tumor microenvironment: Implications for cancer immunotherapy. MedComm 2020, 1, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, X.; Liu, Y.; Dong, S.; Wen, Z.; He, W.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Q.; Shi, M. ROS signaling under metabolic stress: Cross-talk between AMPK and AKT pathway. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelic, M.D.; Mandic, A.D.; Maricic, S.M.; Srdjenovic, B.U. Oxidative stress and its role in cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2021, 17, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, I.S.; Treloar, A.E.; Inoue, S.; Sasaki, M.; Gorrini, C.; Lee, K.C.; Yung, K.Y.; Brenner, D.; Knobbe-Thomsen, C.B.; Cox, M.A.; et al. Glutathione and thioredoxin antioxidant pathways synergize to drive cancer initiation and progression. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Ohta, T.; Tong, K.I.; Kokubu, A.; Odogawa, R.; Tsuta, K.; Asamura, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Hirohashi, S. Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13568–13573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennel, K.B.; Greten, F.R. Immune cell—produced ROS and their impact on tumor growth and metastasis. Redox Biol. 2021, 42, 101891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quante, M.; Varga, J.; Wang, T.C.; Greten, F.R. The gastrointestinal tumor microenvironment. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Molecular pathways: Tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells and reactive oxygen species in regulation of tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 4877–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paardekooper, L.M.; Dingjan, I.; Linders, P.T.A.; Staal, A.H.J.; Cristescu, S.M.; Verberk, W.; van den Bogaart, G. Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Produce Millimolar Concentrations of ROS in Phagosomes Per Second. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, A.; Jancic, C.; Hugues, S.; Guermonprez, P.; Vargas, P.; Moura, I.C.; Lennon-Duménil, A.M.; Seabra, M.C.; Raposo, G.; Amigorena, S. NOX2 controls phagosomal pH to regulate antigen processing during crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell 2006, 126, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otano, I.; Alvarez, M.; Minute, L.; Ochoa, M.C.; Migueliz, I.; Molina, C.; Azpilikueta, A.; de Andrea, C.E.; Etxeberria, I.; Sanmamed, M.F.; et al. Human CD8 T cells are susceptible to TNF-mediated activation-induced cell death. Theranostics 2020, 10, 4481–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraaij, M.D.; Savage, N.D.; van der Kooij, S.W.; Koekkoek, K.; Wang, J.; van den Berg, J.M.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; Kuijpers, T.W.; Holmdahl, R.; van Kooten, C.; et al. Induction of regulatory T cells by macrophages is dependent on production of reactive oxygen species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17686–17691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, B. Tumoral NOX4 recruits M2 tumor-associated macrophages via ROS/PI3K signaling-dependent various cytokine production to promote NSCLC growth. Redox Biol. 2019, 22, 101116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.C.; Wang, L.L.; Zhang, X.D.; Xu, J.L.; Li, P.F.; Liang, H.; Zhang, X.B.; Xie, L.; Zhou, Z.H.; Yang, J.; et al. The relationship between expression of PD-L1 and HIF-1α in glioma cells under hypoxia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kono, K.; Salazar-Onfray, F.; Petersson, M.; Hansson, J.; Masucci, G.; Wasserman, K.; Nakazawa, T.; Anderson, P.; Kiessling, R. Hydrogen peroxide secreted by tumor-derived macrophages down-modulates signal-transducing zeta molecules and inhibits tumor-specific T cell-and natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Immunol. 1996, 26, 1308–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Han, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, L. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in tumor microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2011, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, D.F.; Kimura, K.; Bernhardt, W.M.; Shrimanker, N.; Akai, Y.; Hohenstein, B.; Saito, Y.; Johnson, R.S.; Kretzler, M.; Cohen, C.D.; et al. Hypoxia promotes fibrogenesis in vivo via HIF-1 stimulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3810–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copple, B.L. Hypoxia stimulates hepatocyte epithelial to mesenchymal transition by hypoxia-inducible factor and transforming growth factor-beta-dependent mechanisms. Liver Int. 2010, 30, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Dada, L.A.; Wu, M.; Kelly, A.; Trejo, H.; Zhou, Q.; Varga, J.; Sznajder, J.I. Hypoxia-induced alveolar epithelial-mesenchymal transition requires mitochondrial ROS and hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2009, 297, L1120–L1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radisky, D.C.; Levy, D.D.; Littlepage, L.E.; Liu, H.; Nelson, C.M.; Fata, J.E.; Leake, D.; Godden, E.L.; Albertson, D.G.; Angela Nieto, M.; et al. Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature 2005, 436, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varisli, L.; Tolan, V. Increased ROS alters E-/N-cadherin levels and promotes migration in prostate cancer cells. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2022, 123, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Yin, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, M.; Han, S.; Xiao, H.; et al. Cuproptosis Induced by ROS Responsive Nanoparticles with Elesclomol and Copper Combined with αPD-L1 for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2212267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Tian, T.; Qian, H.; Li, X.; Yu, Y. Multifunctional Au@AgBiS2 Nanoparticles as High-Efficiency Radiosensitizers to Induce Pyroptosis for Cancer Radioimmunotherapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2302141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido, J.; Martinez-Ruiz, L.; Rodriguez-Santana, C.; López-Rodríguez, A.; Hidalgo-Gutiérrez, A.; Cottet-Rousselle, C.; Lamarche, F.; Schlattner, U.; Guerra-Librero, A.; Aranda-Martínez, P.; et al. Melatonin drives apoptosis in head and neck cancer by increasing mitochondrial ROS generated via reverse electron transport. J. Pineal Res. 2022, 73, e12824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Mao, M.; Chen, C.; Huang, A.; Chen, Y.; et al. Metformin induces Ferroptosis by inhibiting UFMylation of SLC7A11 in breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Gan, S.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, Y.; Lu, L.; Wang, Y.; Qi, X.; Feng, Q.; Huang, Q.; Du, B.; et al. Artesunate Inhibits the Cell Growth in Colorectal Cancer by Promoting ROS-Dependent Cell Senescence and Autophagy. Cells 2022, 11, 2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, F.; Soltani, A.; Ghahremanloo, A.; Javid, H.; Hashemy, S.I. The thioredoxin system and cancer therapy: A review. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2019, 84, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Huang, P.Y.; Yan, P.; Chen, P.L.; Shi, Q.Y.; Zhao, Z.A.; Chen, J.X.; Shu, X.; Wang, P.; Yang, B.; et al. Versatile Nanodrugs Containing Glutathione and Heme Oxygenase 1 Inhibitors Enable Suppression of Antioxidant Defense System in a Two-Pronged Manner for Enhanced Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ju, S.; Singh, M.K.; Han, S.; Ranbhise, J.; Ha, J.; Choe, W.; Yoon, K.-S.; Yeo, S.G.; Kim, S.S.; Kang, I. Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252212387

Ju S, Singh MK, Han S, Ranbhise J, Ha J, Choe W, Yoon K-S, Yeo SG, Kim SS, Kang I. Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024; 25(22):12387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252212387

Chicago/Turabian StyleJu, Songhyun, Manish Kumar Singh, Sunhee Han, Jyotsna Ranbhise, Joohun Ha, Wonchae Choe, Kyung-Sik Yoon, Seung Geun Yeo, Sung Soo Kim, and Insug Kang. 2024. "Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 22: 12387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252212387

APA StyleJu, S., Singh, M. K., Han, S., Ranbhise, J., Ha, J., Choe, W., Yoon, K.-S., Yeo, S. G., Kim, S. S., & Kang, I. (2024). Oxidative Stress and Cancer Therapy: Controlling Cancer Cells Using Reactive Oxygen Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(22), 12387. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252212387