The Prognostic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Potential of TRAIL Signalling in Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

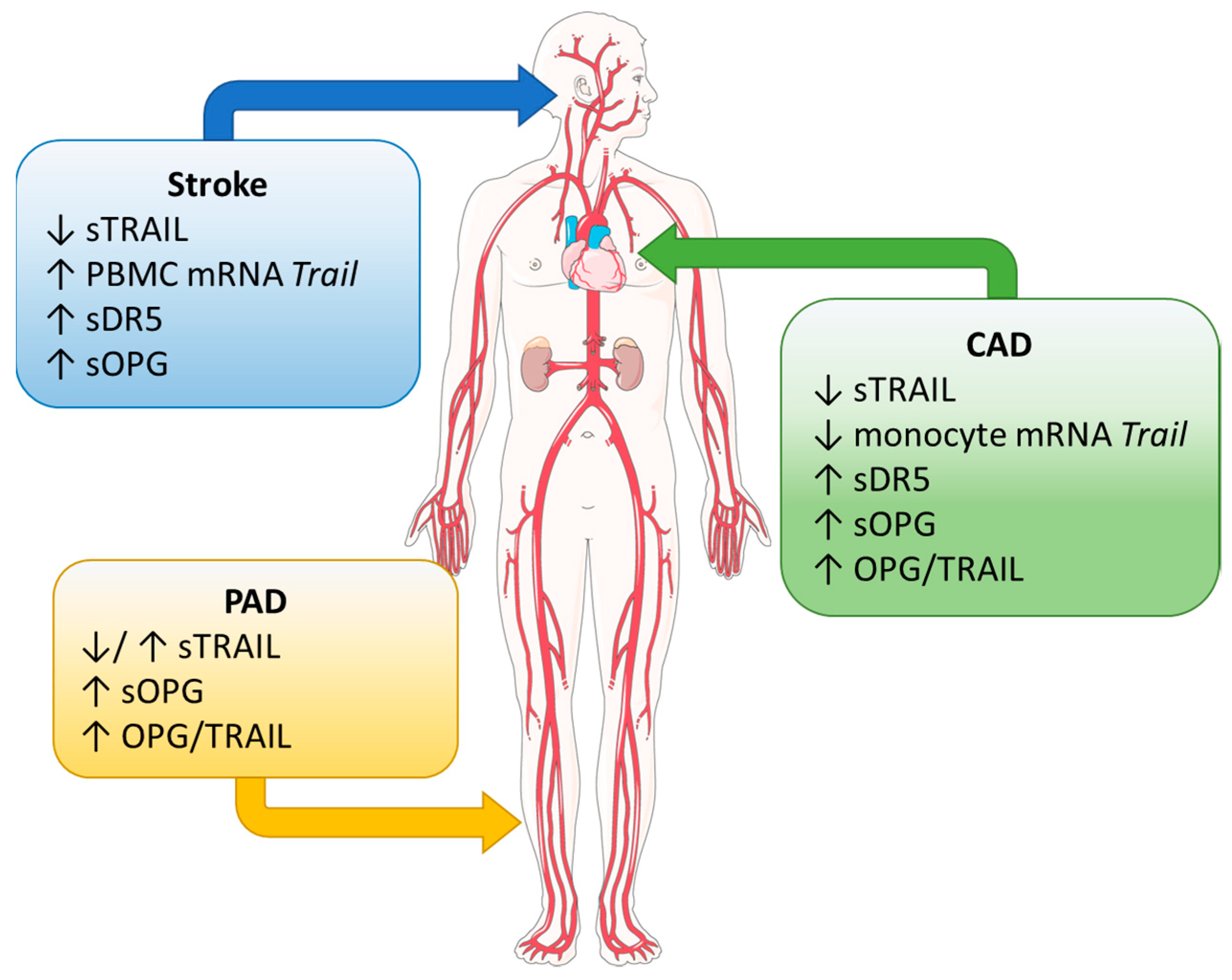

2. Atherosclerosis and Vessel Diseases

2.1. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential

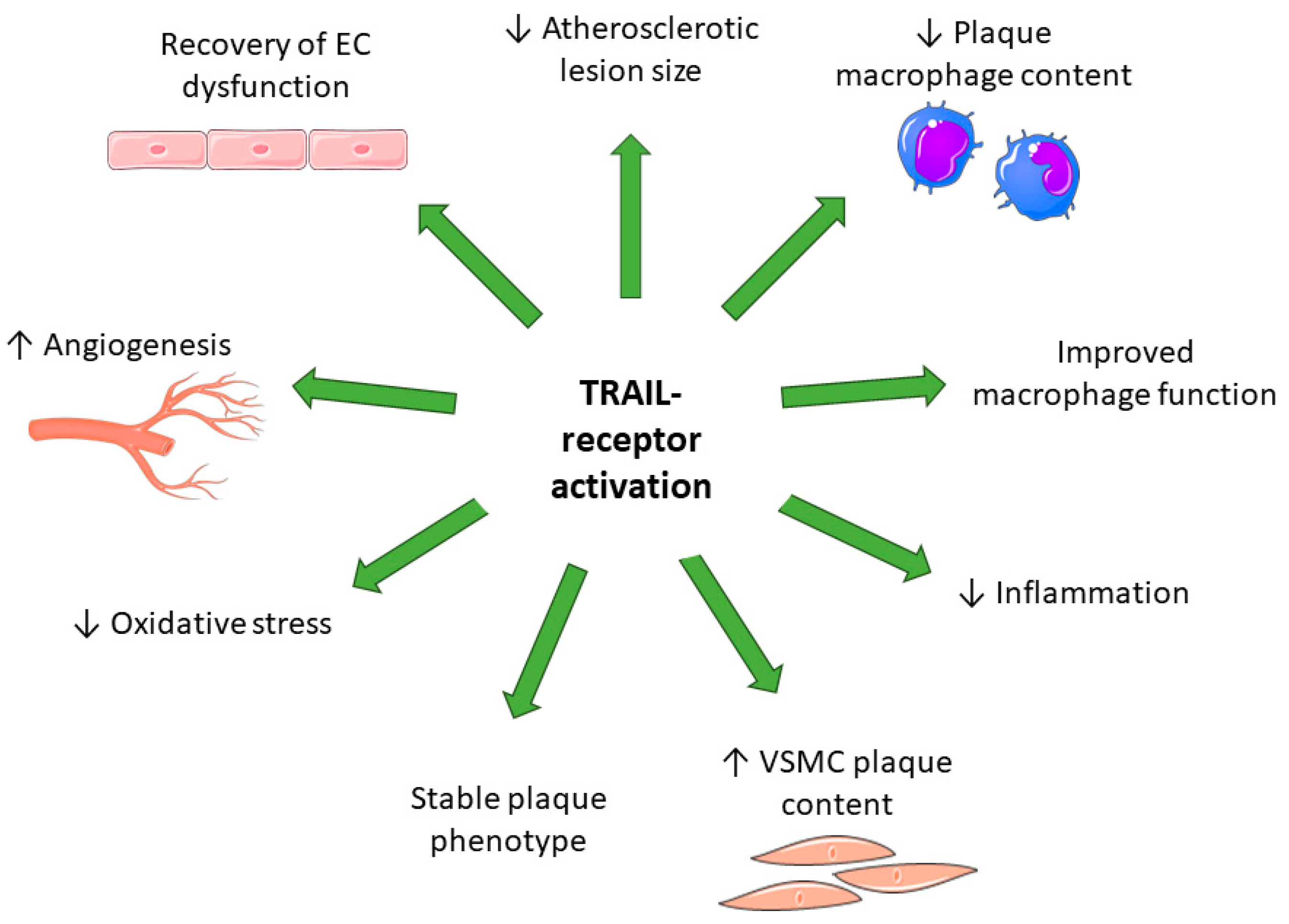

2.2. Therapeutic Potential for Atherosclerotic Disease—Teachings from In Vitro and Pre-Clinical Studies

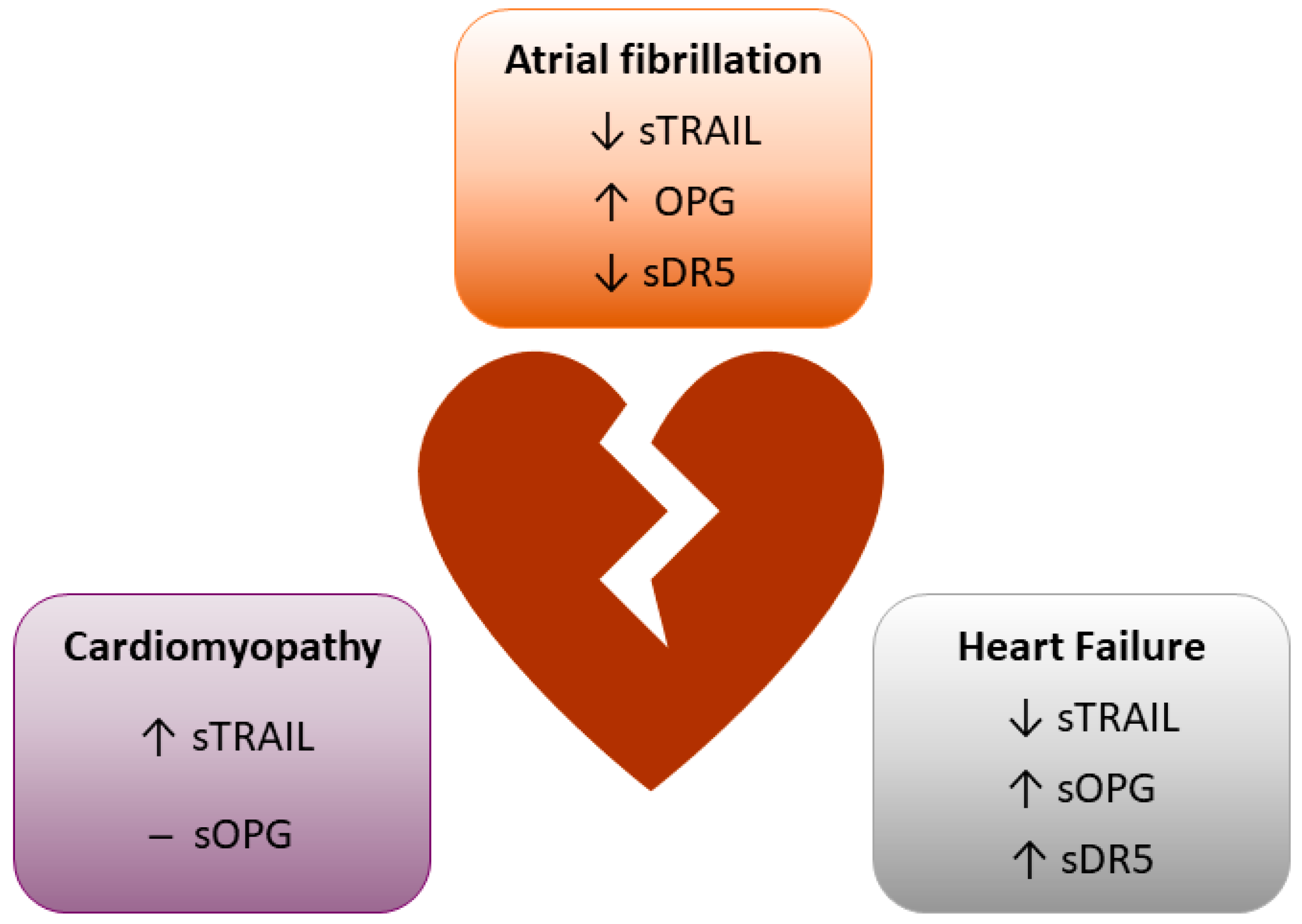

3. TRAIL Signalling in the Myocardium

3.1. Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential

3.2. Therapeutic Potential for Diseases of the Heart—Teachings from In Vitro and Pre-Clinical Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarson, T.R.; Acs, A.; Ludwig, C.; Panton, U.H. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: A systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2018, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitti, R.M.; Marsters, S.A.; Ruppert, S.; Donahue, C.J.; Moore, A.; Ashkenazi, A. Induction of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine family. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 12687–12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiley, S.R.; Schooley, K.; Smolak, P.J.; Din, W.S.; Huang, C.P.; Nicholl, J.K.; Sutherland, G.R.; Smith, T.D.; Rauch, C.; Smith, C.A.; et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity 1995, 3, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosse-Wilde, A.; Kemp, C.J. Metastasis suppressor function of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-R in mice: Implications for TRAIL-based therapy in humans? Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6035–6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snajdauf, M.; Havlova, K.; Vachtenheim, J.; Ozaniak, A.; Lischke, R.; Bartunkova, J.; Smrz, D.; Strizova, Z. The TRAIL in the Treatment of Human Cancer: An Update on Clinical Trials. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 628332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouan-Lanhouet, S.; Arshad, M.I.; Piquet-Pellorce, C.; Martin-Chouly, C.; Le Moigne-Muller, G.; Van Herreweghe, F.; Takahashi, N.; Sergent, O.; Lagadic-Gossmann, D.; Vandenabeele, P.; et al. TRAIL induces necroptosis involving RIPK1/RIPK3-dependent PARP-1 activation. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.; Qiao, J.; Bao, A. Autophagy is a regulator of TRAIL-induced apoptosis in NSCLC A549 cells. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2017, 11, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.; Prado-Lourenco, L.; Khachigian, L.M.; Bennett, M.R.; Bartolo, B.A.D.; Kavurma, M.M. TRAIL Promotes VSMC Proliferation and Neointima Formation in a FGF-2–, Sp1 Phosphorylation–, and NFκB-Dependent Manner. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchiero, P.; Gonelli, A.; Carnevale, E.; Milani, D.; Pandolfi, A.; Zella, D.; Zauli, G. TRAIL Promotes the Survival and Proliferation of Primary Human Vascular Endothelial Cells by Activating the Akt and ERK Pathways. Circulation 2003, 107, 2250–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahraman, S.; Yilmaz, O.; Altunbas, H.A.; Dirice, E.; Sanlioglu, A.D. TRAIL induces proliferation in rodent pancreatic beta cells via AKT activation. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2021, 66, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartland, S.P.; Genner, S.W.; Zahoor, A.; Kavurma, M.M. Comparative Evaluation of TRAIL, FGF-2 and VEGF-A-Induced Angiogenesis In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavurma, M.M.; Schoppet, M.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Khachigian, L.M.; Bennett, M.R. TRAIL Stimulates Proliferation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells via Activation of NF-κB and Induction of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 7754–7762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Ni, J.; Wei, Y.F.; Yu, G.; Gentz, R.; Dixit, V.M. An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science 1997, 277, 815–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, S.; Ferrucci, L.; Secchiero, P.; Corallini, F.; Zuliani, G.; Fellin, R.; Guralnik, J.M.; Bandinelli, S.; Zauli, G. Association of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand with total and cardiovascular mortality in older adults. Atherosclerosis 2010, 215, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmancik, P.; Teringova, E.; Tousek, P.; Paulu, P.; Widimsky, P. Prognostic value of TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) in acute coronary syndrome patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakareko, K.; Rydzewska-Rosołowska, A.; Zbroch, E.; Hryszko, T. TRAIL and Cardiovascular Disease—A Risk Factor or Risk Marker: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.A.; Suwaidi, J.A. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 853–876. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, K.; Ikari, Y.; Jono, S.; Shioi, A.; Ishimura, E.; Emoto, M.; Inaba, M.; Hara, K.; Nishizawa, Y. Association of serum TRAIL level with coronary artery disease. Thromb. Res. 2009, 125, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, O.G.; El-Shehaby, A.; Nabih, M. Possible Role of Osteoprotegerin and Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand as Markers of Plaque Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. Angiology 2010, 61, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajala, O.; Zhang, Y.; Gupta, A.; Bon, J.; Sciurba, F.; Chandra, D. Decreased serum TRAIL is associated with increased mortality in smokers with comorbid emphysema and coronary artery disease. Respir. Med. 2018, 145, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartland, S.P.; Genner, S.W.; Martínez, G.J.; Robertson, S.; Kockx, M.; Lin, R.C.Y.; O’Sullivan, J.F.; Koay, Y.C.; Manuneedhi Cholan, P.; Kebede, M.A.; et al. TRAIL-Expressing Monocyte/Macrophages Are Critical for Reducing Inflammation and Atherosclerosis. iScience 2019, 12, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallentin, L.; Eriksson, N.; Olszowka, M.; Grammer, T.B.; Hagström, E.; Held, C.; Kleber, M.E.; Koenig, W.; März, W.; Stewart, R.A.H.; et al. Plasma proteins associated with cardiovascular death in patients with chronic coronary heart disease: A retrospective study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skau, E.; Henriksen, E.; Wagner, P.; Hedberg, P.; Siegbahn, A.; Leppert, J. GDF-15 and TRAIL-R2 are powerful predictors of long-term mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2017, 24, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldreich, T.; Nowak, C.; Fall, T.; Carlsson, A.C.; Carrero, J.-J.; Ripsweden, J.; Qureshi, A.R.; Heimbürger, O.; Barany, P.; Stenvinkel, P.; et al. Circulating proteins as predictors of cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J. Nephrol. 2019, 32, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edfors, R.; Lindhagen, L.; Spaak, J.; Evans, M.; Andell, P.; Baron, T.; Mörtberg, J.; Rezeli, M.; Salzinger, B.; Lundman, P.; et al. Use of proteomics to identify biomarkers associated with chronic kidney disease and long-term outcomes in patients with myocardial infarction. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.P.; Sharma, A.; Mehta, C.; Bakris, G.; Rossignol, P.; White, W.B.; Zannad, F. Multi-proteomic approach to predict specific cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes and myocardial infarction: Findings from the EXAMINE trial. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vik, A.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Brox, J.; Wilsgaard, T.; Njolstad, I.; Jorgensen, L.; Hansen, J.B. Serum osteoprotegerin is a predictor for incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in a general population: The Tromso Study. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2011, 9, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerre, M.; Hilden, J.; Winkel, P.; Jensen, G.B.; Kjøller, E.; Sajadieh, A.; Kastrup, J.; Kolmos, H.J.; Larsson, A.; Ärnlöv, J.; et al. Serum osteoprotegerin as a long-term predictor for patients with stable coronary artery disease and its association with diabetes and statin treatment: A CLARICOR trial 10-year follow-up substudy. Atherosclerosis 2020, 301, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogelvang, R.; Pedersen, S.H.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Bjerre, M.; Iversen, A.Z.; Galatius, S.; Frystyk, J.; Jensen, J.S. Comparison of osteoprotegerin to traditional atherosclerotic risk factors and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein for diagnosis of atherosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 109, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzniewski, M.; Fedak, D.; Dumnicka, P.; Stepien, E.; Kusnierz-Cabala, B.; Cwynar, M.; Sulowicz, W. Osteoprotegerin and osteoprotegerin/TRAIL ratio are associated with cardiovascular dysfunction and mortality among patients with renal failure. Adv. Med. Sci. 2016, 61, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosbond, S.E.; Diederichsen, A.C.P.; Saaby, L.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Lambrechtsen, J.; Munkholm, H.; Sand, N.P.R.; Gerke, O.; Poulsen, T.S.; Mickley, H. Can osteoprotegerin be used to identify the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in different clinical settings? Atherosclerosis 2014, 236, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.H.; Park, M.-G.; Noh, K.-H.; Park, H.R.; Lee, H.W.; Son, S.M.; Park, K.-P. Low serum TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) levels are associated with acute ischemic stroke severity. Atherosclerosis 2015, 240, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Pang, M.; Ma, A.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Yang, S. Association of TRAIL and Its Receptors with Large-Artery Atherosclerotic Stroke. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufekci, K.U.; Vurgun, U.; Yigitaslan, O.; Keskinoglu, P.; Yaka, E.; Kutluk, K.; Genc, S. Follow-up Analysis of Serum TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Protein and mRNA Expression in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Patients with Ischemic Stroke. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altintas Kadirhan, O.; Kucukdagli, O.T.; Gulen, B. The effectiveness of serum S100B, TRAIL, and adropin levels in predicting clinical outcome, final infarct core, and stroke subtypes of acute ischemic stroke patients. Biomédica 2022, 42, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanne, T.M.; Angerfors, A.; Andersson, B.; Brännmark, C.; Holmegaard, L.; Jern, C. Longitudinal Study Reveals Long-Term Proinflammatory Proteomic Signature After Ischemic Stroke Across Subtypes. Stroke 2022, 53, 2847–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalovic, M.; Mikulenka, P.; Línková, H.; Neuberg, M.; Štětkářová, I.; Peisker, T.; Lauer, D.; Tousek, P. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) in Patients after Acute Stroke: Relation to Stroke Severity, Myocardial Injury, and Impact on Prognosis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, I.; Singh, P.; Tengryd, C.; Cavalera, M.; Yao Mattisson, I.; Nitulescu, M.; Flor Persson, A.; Volkov, P.; Engström, G.; Orho-Melander, M.; et al. sTRAIL-R2 (Soluble TNF [Tumor Necrosis Factor]-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand Receptor 2) a Marker of Plaque Cell Apoptosis and Cardiovascular Events. Stroke 2019, 50, 1989–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajda, J.; Świat, M.; Owczarek, A.J.; Holecki, M.; Duława, J.; Brzozowska, A.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M.; Chudek, J. Osteoprotegerin Assessment Improves Prediction of Mortality in Stroke Patients. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2019, 28, 1160–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.K.; Ueland, T.; Atar, D.; Gullestad, L.; Mickley, H.; Aukrust, P.; Januzzi, J.L. Osteoprotegerin concentrations and prognosis in acute ischaemic stroke. J. Intern. Med. 2010, 267, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arık, H.O.; Yalcin, A.D.; Gumuslu, S.; Genç, G.E.; Turan, A.; Sanlioglu, A.D. Association of circulating sTRAIL and high-sensitivity CRP with type 2 diabetic nephropathy and foot ulcers. Med. Sci. Monit. 2013, 19, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, A.R.; Park, Y.; Chang, J.H.; Lee, S.S. Inverse regulation of serum osteoprotegerin and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand levels in patients with leg lesional vascular calcification: An observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, E.P.; Ashley, D.T.; Davenport, C.; Kelly, J.; Devlin, N.; Crowley, R.; Leahy, A.L.; Kelly, C.J.; Agha, A.; Thompson, C.J.; et al. Osteoprotegerin is higher in peripheral arterial disease regardless of glycaemic status. Thromb. Res. 2010, 126, e423–e427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessner, A.; Hohensinner, P.J.; Rychli, K.; Neuhold, S.; Zorn, G.; Richter, B.; Hulsmann, M.; Berger, R.; Mortl, D.; Huber, K.; et al. Prognostic value of apoptosis markers in advanced heart failure patients. Eur. Heart J. 2009, 30, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, B.; Koller, L.; Hohensinner, P.J.; Zorn, G.; Brekalo, M.; Berger, R.; Mörtl, D.; Maurer, G.; Pacher, R.; Huber, K.; et al. A multi-biomarker risk score improves prediction of long-term mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hage, C.; Michaelsson, E.; Linde, C.; Donal, E.; Daubert, J.C.; Gan, L.M.; Lund, L.H. Inflammatory Biomarkers Predict Heart Failure Severity and Prognosis in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Holistic Proteomic Approach. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmancik, P.; Herman, D.; Stros, P.; Linkova, H.; Vondrak, K.; Paskova, E. Changes and prognostic impact of apoptotic and inflammatory cytokines in patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy. Cardiology 2013, 124, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenemo, M.; Nowak, C.; Byberg, L.; Sundström, J.; Giedraitis, V.; Lind, L.; Ingelsson, E.; Fall, T.; Ärnlöv, J. Circulating proteins as predictors of incident heart failure in the elderly: Circulating proteins as predictors of incident heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, T.; Yndestad, A.; Oie, E.; Florholmen, G.; Halvorsen, B.; Froland, S.S.; Simonsen, S.; Christensen, G.; Gullestad, L.; Aukrust, P. Dysregulated osteoprotegerin/RANK ligand/RANK axis in clinical and experimental heart failure. Circulation 2005, 111, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, T.; Jemtland, R.; Godang, K.; Kjekshus, J.; Hognestad, A.; Omland, T.; Squire, I.B.; Gullestad, L.; Bollerslev, J.; Dickstein, K.; et al. Prognostic value of osteoprotegerin in heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 44, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roysland, R.; Masson, S.; Omland, T.; Milani, V.; Bjerre, M.; Flyvbjerg, A.; Di Tano, G.; Misuraca, G.; Maggioni, A.P.; Tognoni, G.; et al. Prognostic value of osteoprotegerin in chronic heart failure: The GISSI-HF trial. Am. Heart J. 2010, 160, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppet, M.; Ruppert, V.; Hofbauer, L.C.; Henser, S.; Al-Fakhri, N.; Christ, M.; Pankuweit, S.; Maisch, B. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and its decoy receptor osteoprotegerin in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 338, 1745–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lula, J.F.; Rocha, M.O.d.C.; Nunes, M.d.C.P.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Teixeira, M.M.; Bahia, M.T.; Talvani, A. Plasma concentrations of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, and FasLigand/CD95L in patients with Chagas cardiomyopathy correlate with left ventricular dysfunction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmancik, P.; Peroutka, Z.; Budera, P.; Herman, D.; Stros, P.; Straka, Z.; Vondrak, K. Decreased Apoptosis following Successful Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Cardiology 2010, 116, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deftereos, S.; Giannopoulos, G.; Kossyvakis, C.; Raisakis, K.; Angelidis, C.; Efremidis, M.; Panagopoulou, V.; Kaoukis, A.; Theodorakis, A.; Toli, K.; et al. Association of post-cardioversion transcardiac concentration gradient of soluble tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (sTRAIL) and inflammatory biomarkers to atrial fibrillation recurrence. Clin. Biochem. 2013, 46, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rewiuk, K.; Grodzicki, T. Osteoprotegerin and TRAIL in Acute Onset of Atrial Fibrillation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 259843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.; Purmah, Y.; Cardoso, V.R.; Gkoutos, G.V.; Tull, S.P.; Neculau, G.; Thomas, M.R.; Kotecha, D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Kirchhof, P.; et al. Data-driven discovery and validation of circulating blood-based biomarkers associated with prevalent atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Li, Q.; Li, M.; Od, R.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, B.; Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Wang, D. Osteoprotegerin/RANK/RANKL axis and atrial remodeling in mitral valvular patients with atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 166, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartland, S.P.; Lin, R.C.Y.; Genner, S.; Patil, M.S.; Martínez, G.J.; Barraclough, J.Y.; Gloss, B.; Misra, A.; Patel, S.; Kavurma, M.M. Vascular transcriptome landscape of Trail−/− mice: Implications and therapeutic strategies for diabetic vascular disease. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 9547–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolo, B.A.; Cartland, S.P.; Prado-Lourenco, L.; Griffith, T.S.; Gentile, C.; Ravindran, J.; Azahri, N.S.; Thai, T.; Yeung, A.W.; Thomas, S.R.; et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) Promotes Angiogenesis and Ischemia-Induced Neovascularization Via NADPH Oxidase 4 (NOX4) and Nitric Oxide-Dependent Mechanisms. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartland, S.P.; Harith, H.H.; Genner, S.W.; Dang, L.; Cogger, V.C.; Vellozzi, M.; Di Bartolo, B.A.; Thomas, S.R.; Adams, L.A.; Kavurma, M.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, vascular inflammation and insulin resistance are exacerbated by TRAIL deletion in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamhamedi-Cherradi, S.E.; Zheng, S.; Tisch, R.M.; Chen, Y.H. Critical roles of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2003, 52, 2274–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolo, B.A.; Chan, J.; Bennett, M.R.; Cartland, S.; Bao, S.; Tuch, B.E.; Kavurma, M.M. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) protects against diabetes and atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 3157–3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watt, V.; Chamberlain, J.; Steiner, T.; Francis, S.; Crossman, D. TRAIL attenuates the development of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 2011, 215, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manuneedhi Cholan, P.; Cartland, S.P.; Dang, L.; Rayner, B.S.; Patel, S.; Thomas, S.R.; Kavurma, M.M. TRAIL protects against endothelial dysfunction in vivo and inhibits angiotensin-II-induced oxidative stress in vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 126, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartland, S.P.; Erlich, J.H.; Kavurma, M.M. TRAIL Deficiency Contributes to Diabetic Nephropathy in Fat-Fed ApoE−/− Mice. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolo, B.A.; Cartland, S.P.; Harith, H.H.; Bobryshev, Y.V.; Schoppet, M.; Kavurma, M.M. TRAIL-deficiency accelerates vascular calcification in atherosclerosis via modulation of RANKL. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchiero, P.; Candido, R.; Corallini, F.; Zacchigna, S.; Toffoli, B.; Rimondi, E.; Fabris, B.; Giacca, M.; Zauli, G. Systemic tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand delivery shows antiatherosclerotic activity in apolipoprotein E-null diabetic mice. Circulation 2006, 114, 1522–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattazzi, M.; Bennett, B.J.; Bea, F.; Kirk, E.A.; Ricks, J.L.; Speer, M.; Schwartz, S.M.; Giachelli, C.M.; Rosenfeld, M.E. Calcification of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in the innominate arteries of ApoE-deficient mice: Potential role of chondrocyte-like cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 1420–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.J.; Scatena, M.; Kirk, E.A.; Rattazzi, M.; Varon, R.M.; Averill, M.; Schwartz, S.M.; Giachelli, C.M.; Rosenfeld, M.E. Osteoprotegerin inactivation accelerates advanced atherosclerotic lesion progression and calcification in older ApoE−/− mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xiang, G.; Lu, J.; Xiang, L.; Dong, J.; Mei, W. TRAIL protects against endothelium injury in diabetes via Akt-eNOS signaling. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Zhu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhong, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; et al. TRAIL inhibition by soluble death receptor 5 protects against acute myocardial infarction in rats. Heart Vessels 2022, 38, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, M.A.; Thomas, T.P.; Grisanti, L.A. Death receptor 5 contributes to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 136, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, B.; Bernardi, S.; Candido, R.; Zacchigna, S.; Fabris, B.; Secchiero, P. TRAIL shows potential cardioprotective activity. Investig. New Drugs 2012, 30, 1257–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, B.; Fabris, B.; Bartelloni, G.; Bossi, F.; Bernardi, S. Dyslipidemia and Diabetes Increase the OPG/TRAIL Ratio in the Cardiovascular System. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 6529728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, A.; Hou, X.; Yang, D.; Liu, T.; Zheng, D.; Deng, L.; Zhou, T. Role of osteoprotegerin and its gene polymorphisms in the occurrence of left ventricular hypertrophy in essential hypertensive patients. Medicine 2014, 93, e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhao, D.; et al. Blocking the death checkpoint protein TRAIL improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction in monkeys, pigs, and rats. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harith, H.H.; Di Bartolo, B.A.; Cartland, S.P.; Genner, S.; Kavurma, M.M. Insulin promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis via differential regulation of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J. Diabetes 2016, 8, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azahri, N.S.M.; Di Bartolo, B.A.; Khachigian, L.M.; Kavurma, M.M. Sp1, acetylated histone-3 and p300 regulate TRAIL transcription: Mechanisms of PDGF-BB-mediated VSMC proliferation and migration. J. Cell. Biochem. 2012, 113, 2597–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.F.; Wu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, F. TRAIL/DR5 signaling promotes macrophage foam cell formation by modulating scavenger receptor expression. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, H.; Harper, E.; Rochfort, K.D.; Wallace, R.G.; Davenport, C.; Smith, D.; Cummins, P.M. TRAIL inhibits oxidative stress in human aortic endothelial cells exposed to pro-inflammatory stimuli. Physiol. Rep. 2020, 8, e14612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchiero, P.; Gonelli, A.; Carnevale, E.; Corallini, F.; Rizzardi, C.; Zacchigna, S.; Melato, M.; Zauli, G. Evidence for a proangiogenic activity of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Neoplasia 2004, 6, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-L.; Easton, A.S. Evidence that tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) inhibits angiogenesis by inducing vascular endothelial cell apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H.; Kirkiles-Smith, N.C.; McNiff, J.M.; Pober, J.S. TRAIL Induces Apoptosis and Inflammatory Gene Expression in Human Endothelial Cells 1. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 1526–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Wang, X.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, L.Y. Involvement of death receptor signaling in mechanical stretch-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Life Sci. 2005, 77, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, B. Doxorubicin induces cardiotoxicity through upregulation of death receptors mediated apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Thuren, T.; Libby, P. Residual inflammatory risk associated with interleukin-18 and interleukin-6 after successful interleukin-1beta inhibition with canakinumab: Further rationale for the development of targeted anti-cytokine therapies for the treatment of atherothrombosis. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 2153–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, G.; Zhang, J.; Ling, Y.; Zhao, L. Circulating level of TRAIL concentration is positively associated with endothelial function and increased by diabetic therapy in the newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 80, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgin, A.; Yalcin, A.D.; Gorczynski, R.M. Circulating soluble tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing-ligand (TRAIL) is decreased in type-2 newly diagnosed, non-drug using diabetic patients. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2012, 96, e84–e86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, N.; Mori, K.; Emoto, M.; Lee, E.; Kobayashi, I.; Yamazaki, Y.; Urata, H.; Morioka, T.; Koyama, H.; Shoji, T.; et al. Association of serum TRAIL levels with atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2011, 91, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corallini, F.; Celeghini, C.; Rizzardi, C.; Pandolfi, A.; Di Silvestre, S.; Vaccarezza, M.; Zauli, G. Insulin down-regulates TRAIL expression in vascular smooth muscle cells both in vivo and in vitro. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 212, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Katsilambros, N. Repositioning the Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) on the TRAIL to the Development of Diabetes Mellitus: An Update of Experimental and Clinical Evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavurma, M.M.; Rayner, K.J.; Karunakaran, D. The walking dead: Macrophage inflammation and death in atherosclerosis. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2017, 28, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulay, R.; Mena Romo, L.; Hol, E.M.; Dijkhuizen, R.M. From Stroke to Dementia: A Comprehensive Review Exposing Tight Interactions Between Stroke and Amyloid-β Formation. Transl. Stroke Res. 2020, 11, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, F.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Wei, J.; Xing, S.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; Zeng, J. Is Cerebral Amyloid-β Deposition Related to Post-stroke Cognitive Impairment? Transl. Stroke Res. 2021, 12, 946–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossati, S.; Ghiso, J.; Rostagno, A. TRAIL death receptors DR4 and DR5 mediate cerebral microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis induced by oligomeric Alzheimer’s Aβ. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandberg, W.J.; Yndestad, A.; Oie, E.; Smith, C.; Ueland, T.; Ovchinnikova, O.; Robertson, A.K.; Muller, F.; Semb, A.G.; Scholz, H.; et al. Enhanced T-cell expression of RANK ligand in acute coronary syndrome: Possible role in plaque destabilization. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006, 26, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, A.A.; Akturk, H.K.; Paul, T.K.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Ventura, H.O.; Koch, C.A.; Lavie, C.J. Diabetes, Cardiomyopathy, and Heart Failure. In Endotext; Feingold, K.R., Anawalt, B., Blackman, M.R., Boyce, A., Chrousos, G., Corpas, E., de Herder, W.W., Dhatariya, K., Hofland, J., Dungan, K., et al., Eds.; MDtext: South Dartmouth, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Green, J.B.; Halperin, J.L.; Piccini, J.P., Sr. Atrial Fibrillation and Diabetes Mellitus: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzimiri, N.P.D.; Afrane, B.P.D.; Canver, C.C.M.D. Preferential Existence of Death-Inducing Proteins in the Human Cardiomyopathic Left Ventricle. J. Surg. Res. 2007, 142, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spierings, D.C.; de Vries, E.G.; Vellenga, E.; van den Heuvel, F.A.; Koornstra, J.J.; Wesseling, J.; Hollema, H.; de Jong, S. Tissue Distribution of the Death Ligand TRAIL and Its Receptors. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2004, 52, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, A.; Biondi-Zoccai, G.G.; Bussani, R.; Dobrina, A.; Camilot, D.; Feroce, F.; Rossiello, R.; Baldi, F.; Silvestri, F.; Biasucci, L.M.; et al. Increased myocardial apoptosis in patients with unfavorable left ventricular remodeling and early symptomatic post-infarction heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease | Protein | Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAD | TRAIL | Decreased circulating TRAIL in patients with CAD | [20,21,22,23] |

| Negative association of circulating TRAIL with disease severity | [16,17] | ||

| Reduced expression of TRAIL on monocytes from CAD patients | [23] | ||

| DR5 | Increased circulating DR5 identified as a potential prognostic factor in all-cause mortality in MI patients, cardiovascular mortality, and MI and heart failure readmission in chronic kidney disease and diabetes patients | [24,25,26,27,28] | |

| OPG | Positive association of circulating OPG with risk of all-cause and cardiovascular event-associated mortality | [29,30] | |

| Increased OPG associated with cardiovascular risk factors, e.g., diabetes | [30,31] | ||

| Increased OPG a predictor for all-cause mortality in patients with renal failure | [32] | ||

| Single OPG measurement insufficient to diagnose CAD in patients with angina | [33] | ||

| Stroke | TRAIL | Decreased circulating TRAIL in stroke patients | [34,35,36,37,38,39] |

| Circulating levels associated with stroke severity | [34,35,37,39] | ||

| Increased expression of TRAIL on monocytes with reduced circulating TRAIL at stroke onset | [36] | ||

| DR5 | Increased DR5 in carotid plaques and circulation of symptomatic patients | [40] | |

| Elevated in LAA stroke | [35] | ||

| OPG | Elevated in LAA stroke | [35] | |

| High levels at time of admission predicts poorer prognosis and mortality in ischemic stroke | [41,42] | ||

| PAD | TRAIL | Circulating TRAIL reduced in patient with diabetic complication, i.e., foot ulcers and PAD | [43,44] |

| Increased circulating TRAIL in patients with PAD and diabetes compared to diabetes alone | [45] | ||

| OPG | Increased in PAD and diabetic PAD; associated with decreased TRAIL | [44] | |

| Increased in PAD and diabetic PAD; associated with higher TRAIL | [45] | ||

| Heart failure | TRAIL | Inverse association of circulating TRAIL and all-cause mortality and hospitalisation | [46,47,48] |

| TRAIL did not predict mortality in heart failure patients undergoing cardiac resynchronisation therapy | [49] | ||

| DR5 | Positive correlation between plasma DR5 and HF incidence, preserved ejection fraction and left ventricular ejection fraction | [48,50] | |

| OPG | Positive association with circulating OPG and prediction of adverse outcomes and mortality | [51,52,53] | |

| Cardiomyopathy | TRAIL | Increased systemic TRAIL in dilated cardiomyopathy patients | [54] |

| Positive association with circulating TRAIL and left ventricular ejection fraction and left ventricular diastolic diameter | [55] | ||

| OPG | Increased in the myocardium of dilated cardiomyopathy patients, but no systemic change | [54] | |

| Atrial fibrillation | TRAIL | Reduced circulating TRAIL with successful ablation of AF | [56] |

| Reduced trans cardiac gradient of TRAIL with AF recurrence | [57] | ||

| Not useful in predicting the return to sinus rhythm | [58] | ||

| DR5 | Inverse association of DR5 with AF, but no difference in concentration between patients in sinus rhythm and in AF | [59] | |

| OPG | Identified an increasing gradient of atrial expression of OPG with increasing degrees of AF | [60] | |

| Not useful in predicting the return to sinus rhythm | [58] |

| Model | Animal/Cell Type | Model/Treatment | Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo | Trail−/− mice | Chow | Upregulation of glucose transporter Glut1 in aortic tissue by microarray | [61] |

| Peri-vascular cuff; intimal thickening | Reduced intimal thickening; recombinant TRAIL recovered the neointima after cuff placement in Trail−/− mice; TRAIL stimulates VSMC proliferation and migration in vivo | [10] | ||

| HLI | Reduced vascularisation after HLI; TRAIL gene therapy; improved limb perfusion and vascularisation | [62] | ||

| Western diet | Insulin resistance; increased vascular inflammation | [63] | ||

| STZ-induced diabetes | Increased susceptibility to STZ-induced diabetes | [64] | ||

| NOD mice | CY-induced diabetes | Neutralising TRAIL by soluble TRAIL-R enhanced CY-induced diabetes | [64] | |

| Trail−/−Apoe−/− mice | Atherosclerosis; Western diet | Developed larger, macrophage-rich plaques of unstable phenotype (thin cap, large necrotic core, reduced VSMC and collagen content); developed features of type-2 diabetes | [65] | |

| Atherosclerosis; cholate free Western diet | Developed larger atherosclerotic plaque | [66] | ||

| Atherosclerosis; Western diet; bone marrow transplant | TRAIL-expressing bone marrow attenuated atherosclerosis; reduced inflammation | [23] | ||

| Atherosclerosis; Western diet | Increased vascular oxidative stress; increased aortic endothelial dysfunction | [67] | ||

| Atherosclerosis; Western diet | Increased inflammation; diabetic nephropathy | [68] | ||

| Atherosclerosis; Western diet | Increased plaque; calcification | [69] | ||

| Apoe−/− mice | STZ-induced diabetes | Attenuation of atherosclerotic plaque with recombinant TRAIL or adenoviral TRAIL; reduced plaque macrophage content | [70] | |

| Chow | OPG expressed in the brachiocephalic arteries, associated with chondrocyte-like cells | [71] | ||

| Opg−/−Apoe−/− mice | Atherosclerosis; chow | Increased atherosclerosis and calcification; reduced plaque cellularity | [72] | |

| Rats | STZ-induced diabetes | Endothelial dysfunction was attenuated with recombinant TRAIL treatment | [73] | |

| Acute myocardial infarction | Soluble DR5 reduced infarct size, myocardial damage, and expression of apoptotic mediators | [74] | ||

| C57BL/6 mice | MD5-1 antibody and Bioymifi (small molecule DR5 agonist) | DR5 activation increased heart weight, cardiac hypertrophy, left ventricular ejection fraction, and fractional shortening | [75] | |

| Apoe−/− mice | STZ-induced diabetes; | Recombinant TRAIL and AAV TRAIL reduced cardiac fibrosis and apoptosis in diabetes | [76] | |

| STZ-induced diabetes | Increased OPG expression associated with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy | [77] | ||

| Spontaneously hypertensive rats | Recombinant OPG | Increased left ventricular weight | [78] | |

| Rats, pigs and monkeys | Myocardial infarction | DR5 inhibition reduced infarct size, cardiomyocyte death, and fibrosis and prevented ventricular wall thinning; preserved ejection fraction and fractional shortening | [79] | |

| In vitro | VSMC | Recombinant TRAIL | Increases proliferation and migration in human aortic VSMCs | [10] |

| Recombinant TRAIL | Increases proliferation and migration via activation of insulin-like growth factor in human aortic VSMCs | [14] | ||

| Insulin | Chronic insulin suppresses TRAIL expression and promotes apoptosis in human aortic VSMCs | [80] | ||

| Recombinant PDGFB | Increases proliferation and migration via induction of TRAIL transcription and gene expression in human aortic VSMCs | [81] | ||

| Monocyte/ macrophage | Recombinant IL-18 | Suppressed TRAIL gene expression and transcription via blocking NFκβ binding to the TRAIL promoter in human monocytes | [23] | |

| Recombinant TRAIL | Increased lipid uptake and foam cell formation; macrophage apoptosis in RAW264.7 and THP-1 cells | [82] | ||

| Basal, LPS and acLDL | Trail−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages were more inflammatory and had a reduced ability to efferocytose; had impaired cholesterol and impaired ability to migrate compared to Trail+/+ bone marrow-derived macrophages | [23] | ||

| ECs | Recombinant TRAIL | TRAIL treatment inhibited TNFα/hyperglycaemia-induced inflammation and ROS production in HAECs | [83] | |

| TRAIL inhibited high glucose-induced ROS and cell death, in part via Akt and eNOS phosphorylation in HUVEC | [73] | |||

| TRAIL protected against AngII-induced oxidative stress; reduced AngII-induced monocyte adhesion and improved EC integrity by redistributing VE-cadherin expression to the cell surface | [67] | |||

| Increased HMEC-1 proliferation, migration, and tubule formation via NOX-4-inducible eNOS phosphorylation and nitric oxide production | [62] | |||

| Increased HMEC-1 proliferation, migration, and tubule formation | [13] | |||

| Increased HUVEC migration, invasion, and tubule formation | [84] | |||

| Increased apoptosis of HMEC/d3 cells | [85] | |||

| Increased HUVEC apoptosis | [86] | |||

| Cardiomyocytes | Recombinant TRAIL and Bioymifi | DR5 activation via EGFR increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation for hypertrophy; cell death or viability not affected | [75] | |

| AAV-OPG vector and OPG siRNA | OPG increased cell surface size and expression of hypertrophy proteins in rat cardiomyocytes | [78] | ||

| Recombinant TRAIL and soluble DR5 (sDR5) | TRAIL increased, while sDR5 neutralised stretch-induced apoptosis in rat cardiomyocytes | [87] | ||

| Doxorubicin | Increased DR4 and DR5 mRNA/protein associating with enhanced TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes | [88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kelland, E.; Patil, M.S.; Patel, S.; Cartland, S.P.; Kavurma, M.M. The Prognostic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Potential of TRAIL Signalling in Cardiovascular Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076725

Kelland E, Patil MS, Patel S, Cartland SP, Kavurma MM. The Prognostic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Potential of TRAIL Signalling in Cardiovascular Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(7):6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076725

Chicago/Turabian StyleKelland, Elaina, Manisha S. Patil, Sanjay Patel, Siân P. Cartland, and Mary M. Kavurma. 2023. "The Prognostic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Potential of TRAIL Signalling in Cardiovascular Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 7: 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076725

APA StyleKelland, E., Patil, M. S., Patel, S., Cartland, S. P., & Kavurma, M. M. (2023). The Prognostic, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Potential of TRAIL Signalling in Cardiovascular Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(7), 6725. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24076725