Abstract

The cure rate for metastatic or relapsed osteosarcoma has not substantially improved over the past decades despite the exploitation of multimodal treatment approaches, allowing long-term survival in less than 30% of cases. Patients with osteosarcoma often develop resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, where personalized targeted therapies should offer new hope. T cell immunotherapy as a complementary or alternative treatment modality is advancing rapidly in general, but its potential against osteosarcoma remains largely unexplored. Strategies incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) modified T cells, and T cell engaging bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) are being explored to tackle relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma. However, osteosarcoma is an inherently heterogeneous tumor, both at the intra- and inter-tumor level, with no identical driver mutations. It has a pro-tumoral microenvironment, where bone cells, stromal cells, neovasculature, suppressive immune cells, and a mineralized extracellular matrix (ECM) combine to derail T cell infiltration and its anti-tumor function. To realize the potential of T cell immunotherapy in osteosarcoma, an integrated approach targeting this complex ecosystem needs smart planning and execution. Herein, we review the current status of T cell immunotherapies for osteosarcoma, summarize the challenges encountered, and explore combination strategies to overcome these hurdles, with the ultimate goal of curing osteosarcoma with less acute and long-term side effects.

1. Introduction

Bone sarcomas represent about 6% of all pediatric cancers, of which osteosarcoma makes up the majority (56%), making it the most common primary bone malignancy for children and young adults. The patients diagnosed with metastatic or relapsed osteosarcoma still have dismal outcomes despite multimodal treatment approaches such as conventional multi-agent chemotherapy, surgery, or high-dose chemotherapy with stem cell transplantation, achieving long-term survival in less than 30% of cases [1]. Moreover, given the young age of onset for osteosarcoma, the side effects of these treatments can be devastating and long-lasting. Even patients in remission can suffer from long-term complications including secondary malignancies, disfigurement (from surgery), and psychosocial trauma [2,3]. As such, there is a desperate need for more effective and less toxic therapy for both localized and metastatic high-risk osteosarcoma. Immunotherapy may offer viable alternatives. Since the reports of Dr. Coley on bacterial toxins inducing tumor regression [4], many immunotherapy attempts have been made in soft tissue and bone sarcomas, but so far without consistent or durable response [5,6]. Although interferons (IFN) are well known to have anti-angiogenic, anti-tumor, and immune-stimulating properties [5], the EURAMOS-1 clinical trial incorporating IFN-α2b as a maintenance therapy failed to show clinical benefit [7]. Monoclonal IgG antibodies targeting specific tumor surface antigens have also been tested, including trastuzumab to target HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) [8], cetuximab to target epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [9], glembatumumab vedotin (GV) to target glycoprotein nonmetastatic B (gpNMB) [10], denosumab to target the cytokine RANKL (receptor activator of NFκB ligand) (NCT02470091), and dinutuximab to target disialogangliosides (GD2) (NCT 02484443), but anti-tumor effects have been transient or inconsistent [11,12,13]. Recently, trastuzumab deruxtecan (an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of trastuzumab and topoisomerase I inhibitor deruxtecan) was FDA approved in patients with HER2-low metastatic breast cancer [14]. A phase 2 study of trastuzumab deruxtecan is ongoing for the treatment of HER2(+) osteosarcoma (NCT04616560), but the preliminary results are disappointing: seven out of eight patients showed progressive disease, while one showed a stable disease [15].

T cell immunotherapy has proven activity for many high-risk malignancies, but their efficacy against osteosarcoma remains largely unexplored. Although preclinical studies using immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), antigen-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR), or bispecific antibody (BsAb) have demonstrated the impressive anti-tumor capacity of T cells, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) remains a major barrier. Bone tumors, including osteosarcomas, grow in a bone microenvironment, unique among primary tumors while common for metastases with preference for the bony niche. This TME is composed of a variety of cells including bone cells (osteoblasts, osteoclasts, osteocytes), stromal cells (mesenchymal stromal cells, fibroblasts), vascular cells (endothelial cells and pericytes), immune cells (dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs), and NK cells), and a mineralized extracellular matrix (ECM). Cross-talks between osteosarcoma and the TME are channeled through diverse environmental signals such as cytokines, chemokines, and soluble growth factors [13] that promote tumor growth and metastasis while simultaneously thwarting immune surveillance. This osteosarcoma-specific TME impedes T cell infiltration into tumors, accelerates immune effector cell exhaustion and anergy, and derails anti-tumor immunity, creating both a major roadblock and a potential tumor vulnerability.

Herein, we review the promise and the limitations of T cell immunotherapies for osteosarcoma, focusing on ICIs, BsAbs, and CAR T cells, and osteosarcoma-specific TME. We explore strategies to overcome the immune-hostile TME and combination approaches to create synergy with T cell immunotherapy for osteosarcoma.

2. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Osteosarcoma

Upregulation of programmed cell death-1 receptor (PD-1) on CD8(+) T cells promotes T cell exhaustion and dysfunction in chronic inflammation [16,17,18,19]. PD-1 and tumor PD-L1 interaction promotes T cell tolerance through suppressing release of immunostimulatory cytokines while directly inhibiting T cell cytotoxicity [20]. ICIs reverse this process by reinvigorating cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), reviving immune response directed at neoantigens distinct from those on host tissues [21,22]. Despite the low tumor mutational burden (TMB) in pediatric cancers in general, neo-epitopes arising from genetic instability in osteosarcoma could offer potential targets for T cell-mediated cytotoxicity, potentially exploitable by ICI therapies [23,24,25].

After T cell receptor (TCR) activation, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) (CD152), type I transmembrane glycoprotein, is upregulated and constitutively expressed on CTLs and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and after binding to CD80 and CD86 with higher affinity and avidity than CD28 results in T cell suppression and DC dysfunction [26,27,28,29]. Blockade of the CTLA4 receptor increased the number of CD8(+) T cells while reducing Tregs, and combination with tumor lysate-loaded DC inhibited metastasis and prolonged survival of mice with fibrosarcoma [30].

PD-1 is also expressed on T cells following TCR engagement and activation. PD-1 and PD-L1 ligation exerts inhibitory signals for T cell activation (Figure 1) [29]. Overexpression of PD-1 and PD-L1 and their interactions are well-characterized immune escape mechanisms of osteosarcoma [29,31,32]. Besides the direct inhibition of effector T cells, PD-1/PD-L1 interactions reduce the capacity of CD4(+) T cells to secrete IL-21 necessary for CTL response [33] and affect cytotoxicity of NK cells by reducing granzyme B secretion [34]. PD-1 was increased in circulating T cells in osteosarcoma patients, and PD-L1 expression in osteosarcoma was related to early metastasis and poorer outcome [32,35,36]. While PD-L1 density in osteosarcoma cell lines varies widely from low to high, the drug-resistant variants trend towards higher values compared to their parent counterparts [37]. A study using CRISPR/Cas9 system to target the PD-L1 gene in osteosarcoma cells revealed that PD-L1 regulates osteosarcoma growth and drug resistance [38]. The expression levels of PD-L1 correlated with TILs [37], and the blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions improved the activity of osteosarcoma-reactive CTLs, resulting in an improved outcome in preclinical models [39,40]. PD-1 inhibitor could effectively control osteosarcoma pulmonary metastasis by increasing CD4(+) and CD8(+) TILs and enhancing the cytolytic activity of CD8(+) T cells in the lung [41]. Both human and murine metastatic osteosarcomas express the PD-L1, which could functionally impair tumor-infiltrating CTLs by engaging their surface PD-1. This model was supported by studies where the PD-L1 blockade improved the function of osteosarcoma TILs in vivo, decreasing tumor burden and increasing survival of mice carrying metastatic osteosarcoma [39]. The combination of triple antibodies, anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-OX-40 agonistic antibody, led to a prolonged survival of mice in preclinical studies, suggesting the therapeutic potential of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway for high-risk osteosarcoma [40].

However, clinical studies of ICIs have failed to produce satisfactory results in osteosarcoma. Phase I study of ipilimumab in pediatric patients with advanced or relapsed solid tumors including eight osteosarcomas failed to show clinical benefit as a single agent, despite observing an increase in activated HLA-DR(+) Ki67(+) T cells without concomitant upregulating Tregs among the patients [42]. A recent phase II clinical trial of anti-PD1 pembrolizumab for advanced sarcomas reported that 7 out of 40 patients with soft tissue sarcoma (18%) and only 2 out of 40 patients (5%) with bone sarcomas had objective responses [43]. The study included twenty-two patients with osteosarcoma; one patient (5%) had a partial response, six patients (27%) had a stable disease, and fifteen patients (68%) showed disease progression. Another study of pembrolizumab in advanced osteosarcoma also failed to show clinical benefit despite high PD-L1 expression in tumors (11 of 12 patients): median progression-free survival (PFS) was 1.7 months and median overall survival (OS) was 6.6 months [44]. A clinical trial of the PD-L1 inhibitor (avelumab) for recurrent or progressive osteosarcoma was no more successful, where 17 out of the 18 treated patients showed disease progression while on study (NCT03006848). The low clinical activity of single PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade in most sarcoma subtypes suggests that PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor alone cannot adequately revive exhausted or tolerized effector T cells in these patients. These results contrast with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas showing good clinical response accompanied by high numbers of TILs [43], emphasizing the need to develop strategies to enhance T cell infiltration. Although the combination of two ICIs acting through different mechanisms, such as anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1, has shown synergy in preclinical models of osteosarcoma as well as in those of melanoma [40,45], such combinations have had mixed response so far in bone sarcomas. A combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab failed to show efficacy in patients with osteosarcoma [46], and a combination of durvalumab (anti-PD-1) and tremelimumab (anti-CTLA4) resulted in two partial responses out of five osteosarcoma patients treated [47]. Several cases reported that the combination of anti-CTLA4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies induced remission and tumor stabilization in patients with metastatic osteosarcoma [48,49], while the addition of camrelizumab (anti-PD-1 inhibitor) to the inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2)] using apatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)) was shown to prolong PFS of patients with advanced osteosarcoma compared with apatinib alone [50]. The overall findings suggest that a combination strategy rather than a stand-alone therapy may be the path to the future. The data on clinical trials of ICIs for osteosarcoma are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) in osteosarcoma.

3. Adoptive T Cell Immunotherapy for Osteosarcoma

While ICIs are nonspecific, adoptive T cell immunotherapy (ATC) using CAR or BsAb is tumor-antigen-specific, directly driving T cells to the tumors and inducing potent cytotoxicity. CAR and BsAb are engineered to recognize tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and exert T cell-mediated cytotoxicity in a major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-independent manner. Although CAR T cells achieved extraordinary clinical success in hematologic malignancies receiving FDA approvals, they exhibit generally inconsistent and non-durable effects on solid cancers due to tumoral heterogeneity, physical barrier, aberrant vasculature, and the immunosuppressive TME [55,56,57,58]. Anti-tumor efficacy of ATC primarily derives from recognition by VH (variable region of heavy chain) and VL (variable region of light chain) of target antigen-specific antibodies. Ideal TAAs carry epitopes exclusively expressed on tumor cell surface to allow engineered antibodies or receptors to drive T cells selectively into tumors while minimizing off-tumor toxicities. To avoid tumor escape, TAA should be ideally expressed homogenously within and between tumors among patients. The targets reported so far for ATC in osteosarcoma include HER2, GD2, B7-H3 (CD276), interleukin-11 receptor α-chain (IL-11Rα), insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 1 (ROR1), erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular class A2 (EphA2), natural killer group 2D ligand (NKG2DL), activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule (ALCAM, CD166), folate receptor-α (FRα), chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), and CD151 [59,60,61]. Among them, HER2, GD2, and B7H3 have been studied the most for osteosarcoma [62,63,64,65,66,67].

Although osteosarcoma cell lines and tissue sections were HER2-positive by immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry [11,62], HER2 gene amplification was rarely observed in osteosarcoma, and the expression levels were much lower than those of HER2(+) breast cancers [68], accounting for the clinical insensitivity of OS to trastuzumab [8]. Despite its HER2 antigen density being too low for conventional IgG-mediated cytotoxicity, osteosarcoma was effectively killed by HER2-CAR T cells, which, when injected intratumorally, induced the regression of established osteosarcoma xenografts, prolonging survival of the mice [11]. HER2-CAR T cells also decreased the sarcosphere forming capacity and bone tumor generating ability, suggesting the potential to target osteosarcoma stem cells [65]. A phase I/II study of HER2-CAR T cells without lymphodepletion resulted in a stable disease in 3 and progressed disease in 12 among 16 patients with recurrent/refractory HER2(+) osteosarcoma (NCT00902044). Although these results were modest, HER2-CAR T cells could traffic to tumor sites and persist for more than 6 weeks in a dose-dependent manner [64]. In the same trial, five osteosarcomas, three rhabdomyosarcomas, one Ewing sarcoma, and one synovial sarcoma were treated with HER2-CAR T cells following lymphodepletion. Among them, three had a stable disease, five had a progressive disease, while one rhabdomyosarcoma and one osteosarcoma patient had complete remission for 12 months and 32 months, respectively [69].

GD2, another promising target for CAR and BsAb, is overexpressed in many cancers including osteosarcoma while being limited in normal tissues [62,70,71]. GD2 has a role in signal transduction and cell adhesion, and overexpression of GD2 increases the phosphorylation of paxillin and focal adhesion kinase (FAK), promoting migration and invasion of osteosarcoma cells [72]. The third-generation GD2-CAR T cells using anti-GD2 clone 14G2a successfully recognized GD2(+) sarcoma cell lines and showed cytotoxicity in vitro, but the accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) attenuated the anti-tumor effect of GD2-CAR T cells in vivo [73]. This inhibition phenomenon was observed in a clinical trial of GD2-CAR T cells in neuroblastoma: GD2-CAR T cells with or without lymphodepletion resulted in modest antitumor responses, with a striking expansion of CD45/CD33/CD11b/CD163 (+) myeloid cells in all patients [74]. The fourth-generation GD2-CAR T cells using the hu3F8 clone can also effectively target osteosarcoma cells and induce PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on GD2-CAR T cells, limiting T cell activity. Combination with low-dose doxorubicin decreased PD-L1, enhancing the potency of GD2-CAR T cells on osteosarcoma in vitro [66]. Recently, Del Bufalo et al. reported exceptional results of GD2-CAR T cells in patients with relapsed or refractory neuroblastoma. Twenty-seven patients were treated with third-generation GD2-CAR T cells, and the overall response was 63%; nine patients had a complete response, eight had a partial response; toxicities were tolerable, and the inducible caspase 9 suicide gene was needed only in one patient (GD2-CART01) [75]. Another third-generation GD2-CAR T cells combined with a safety switch (GD2-CAR.OX40.28.z.ICD9) are being tested for solid tumors including osteosarcoma in a phase I clinical trial (NCT02107963).

B7-H3 (CD276) CAR T cells are also being tested for the treatment of osteosarcoma. B7-H3 is a checkpoint molecule expressed at high levels on pediatric solid tumors including osteosarcoma [76,77], and it contributes to tumor immune evasion and metastasis, correlating with poor prognosis [78]. B7-H3-targeting CAR T cells have shown anti-tumor activity in osteosarcoma xenograft models [67,79]. A phase I clinical trial is currently recruiting patients with solid tumors that express B7-H3 (NCT04483778).

On the other hand, T-BsAb represents another promising alternative which effectively drives T cells to the tumor sites with less toxicity. T-BsAbs are also mostly known for their use in hematological malignancies similarly to CAR T cells, and blinatumomab (a CD3 × CD19 BsAb built on scFv framework) was FDA approved in 2014 and has been successful against relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) [80,81]. For solid tumors, catumaxomab (CD3xEpCAM BsAb) targeting epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM)-positive cancers showed benefit in reducing malignant ascites secondary to epithelial cancers, with an acceptable safety profile [82,83,84]. To improve efficacy and to reduce clinical toxicities, BsAb-armed T cells, using chemically conjugated BsAb, anti-GD2 × anti-CD3 [hu3F8 × mouse OKT3 (NCT02173093)], anti-HER2 × anti-CD3 [trastuzumab × mouse OKT3 (NCT00027807)], or anti-EGFR × anti-CD3 [cetuximab × mouse OKT3 (NCT04137536)], were developed and tested in clinical studies, proven effective and safe in breast, neuroblastoma, prostate, and pancreatic cancers [85,86,87,88]. GD2-BsAb-armed T cells were tested for their efficacy on GD2-positive tumors and induced a significant PET response in one out of three osteosarcoma patients (NCT02173093) [89]. To harness the potential of BsAb against solid tumors, the BsAb structural format was found to be critical [90,91]. Despite similar in vitro anti-tumor properties of GD2-BsAb formats, including monomeric BiTE, dimeric BiTE, IgG heterodimer, IgG-[H]-scFv, or chemical conjugate, the IgG-[L]-scFv format, where the anti-CD3 (huOKT3) scFv was attached to the light chain of a tumor binding IgG, proved the most effective in vivo, driving more T cells into tumors and producing more durable anti-tumor responses [91]. For osteosarcoma cell lines that are HER2-positive and/or GD2-positive, IgG-[L]-scFv GD2-BsAb (hu3F8 × huOKT3) or HER2-BsAb (trastuzumab × huOKT3) administered intravenously successfully drove T cells into tumors to exert potent cytotoxicity in vivo [62]. T cells armed ex vivo (EAT) with the IgG-[L]-scFv-formatted GD2-BsAb (GD2-EATs) or HER2-BsAb (HER2-EATs) also successfully ablated both osteosarcoma cell-line-derived xenografts (CDXs) and patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) with significantly lower cytokine release while increasing the overall survival [62,91]. Although a phase I/II study of this IgG-[L]-scFv-formatted GD2-BsAb (Nivatrotamab) in patients with relapsed/refractory neuroblastoma, osteosarcoma, and other GD2(+) solid tumors was temporarily suspended because of company business priorities (NCT03860207), clinical results are anticipated. The results of clinical trials of BsAb or CAR T cell therapy for osteosarcoma conducted to date are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinical trials of adoptive T cell therapy for osteosarcoma.

4. Tumor Microenvironment in Osteosarcoma

Despite the excitement regarding the clinical utility of T cell immunotherapy, the overall response rate of ICIs is around the 20% range across solid tumors [93], where the promise of ATC remains elusive as well. The challenges of successful T cell immunotherapy in osteosarcoma include poor immunogenicity, paucity of neoantigens and TILs, obvious tumor heterogeneity, and the osteosarcoma-specific, immunosuppressive TME [94].

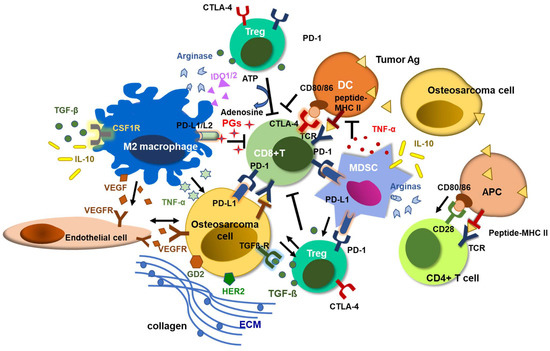

As a seed, osteosarcoma flourishes in soil called the TME. The TME of osteosarcoma consists of a special, complex, and highly structured osseous environment, populated by osteocytes, stromal cells, vascular cells, immune cells, and mineralized architecture, ECM [95] (Figure 1). Bone matrix remodeling is a unique feature of osteosarcoma. The activation of the RANK-RANKL signaling pathway leads to osteoclast activation, resulting in excessive bone resorption and the release of bone matrix growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β1 (TGFβ1), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF1), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) or bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), which in turn promote tumor cell proliferation and further bone destruction [96]. These growth factors not only inhibit osteogenic differentiation but also prohibit T cell proliferation and differentiation, sabotaging host immune surveillance [97]. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) secrete cytokines, chemokine ligand 5 (CCL5), IL-6, and VEGF that promote growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis of osteosarcoma, while the MSC-derived osteoblasts deposit and mineralize the ECM [98]. This osteoid tumor matrix not only fuels tumor growth and metastasis but also limits the trafficking and infiltration of T cells, playing a role as an ideal milieu for osteosarcoma progression while putting up a potentially insurmountable barrier to T cell immunotherapy [99,100].

Figure 1.

Tumor microenvironment of osteosarcoma. Osteosarcoma tumor tissues have large populations of tumors infiltrating myeloid cells (TIMs), including MDSCs and TAMs. Immunosuppressive TIMs and dense ECM around osteosarcoma cells impede T cell infiltration and cytotoxic activity. Tumor infiltrating T cells express PD-1, and the interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 expressed on tumor cells and TIMs exhaust cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells, inducing tumor-immune tolerance. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) release TGF-β and convert ATP to adenosine via CD39 and CD73, inhibiting T cell cytotoxicity and promoting tumor progression [101]. M2 polarized TAMs and MDSCs also release immune-suppressive cytokines and chemokines including TGFβ, TNF-α, IL-10, prostaglandins, arginase, and VEGF, inducing osteosarcoma progression and immune evasion [102].

Targeting the building blocks and the regulatory elements of the ECM has been explored for osteosarcoma. These targets include collagens, fibronectin, laminins, and proteoglycans [103]. Losartan, the angiotensin II receptor blocker, inactivates cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), decreases stromal collagen and hyaluronan production, and reduces TGFβ1, connective tissue growth factor (CCN2, cellular communication network factor 2), and endothelin-1 (ET-1), thereby lowering mechanical compression in tumors and increasing vascular perfusion [104]. Losartan treatment leads to a dose-dependent reduction in stromal collagen in desmoplastic models of human breast, pancreatic and skin cancers, and enhanced the efficacy of chemotherapy in multiple cancer models [105,106]. It also blocks monocyte migration into osteosarcomas and shows significant benefit against canine metastatic osteosarcoma in combination with TKI toceranib [107].

Besides the mechanical stroma, activated VEGF pathway also plays a pivotal role in osteosarcoma progression. Cancer cell metabolism is characterized by an enhanced uptake and utilization of glucose [108], and the persistent activation of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells is linked to the activation of oncogenes or loss of tumor suppressors [109,110]. Heightened metabolism of cancer cells creates a hypoxic and acidic TME, increasing the expression of hypoxic inducible factors (HIFs), VEGFs, and other pro-angiogenic factors, which promote abnormal angiogenesis contributing to chaotic tumor microvasculature [95]. In osteosarcoma, hypoxia and lactic acidosis promote highly vascularized TME, accelerate hypoxic nutrient consumption and waste accumulation, which combine to suppress CTL proliferation and activity [95]. Chemokines (CCL3 and CCL5) and other proangiogenic factors also upregulate VEGF and promote neovasculature in osteosarcoma [111,112,113], and high expression of VEGF and VEGFR2 is associated with poor prognosis [114,115,116]. Dual silencing of the VEGF and Survivin genes effectively inhibited the proliferation, migration, angiogenesis and survival of the osteosarcoma cells [117], suggesting a potential of VEGF pathway blockade as another therapeutic maneuver to salvage T cell immunotherapy against osteosarcoma.

Beyond mechanical stroma and angiogenesis, the immunosuppressive TME is another challenge. The osteosarcoma TME is mainly orchestrated by MDSCs and M2 macrophages. While immune-inflamed ‘hot’ tumors have significant numbers of CD8(+) T cells in the tumor stroma and express pro-inflammatory cytokines, responding well to T cell immunotherapies, osteosarcoma belongs to ‘cold’ tumors characterized by the paucity of TILs, accompanied by immunosuppressive tumor infiltrating myeloid cells, such as TAMs and MDSCs, as well as regulatory T cells (Tregs) [118,119,120]. Tumors secrete high levels of colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), which converts M1 macrophages (classically activated and tumoricidal) to M2 macrophages (alternately activated, tumor-promoting) along with Th2 cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-10, TGFβ1, and PGE2) and stimulates tumor growth and metastasis [121,122]. CD14/CD68 double-positive TAMs are the main immune infiltrates in osteosarcoma, and RNA analyses revealed that type 2 TAMs are the most abundant immune infiltrates [123]. M2 TAMs release proangiogenic factors, such as FGF, matrix metallopeptidase 9 and 12 (MMP-9, MMP-12), and VEGF to increase angiogenesis and vascular extravasation while suppressing CTLs and maintaining Tregs [124,125,126]. TAM-modulating agents including mifamurtide (MTP-PE), ATRA, metformin, gefitinib, esculetin, zoledronic acid, and CAR-macrophages have been tested in osteosarcoma with promising results in preclinical studies [127].

In addition, despite the limited efficacy of radiotherapy in treating osteosarcoma, there have been reports of immunomodulatory effects of radiation on the TME as well as its promising synergy with T cell immunity [128,129,130]. Radiotherapy has the potential to ignite tumor immune recognition by generating immunogenic signals and releasing neoantigens [130]. It triggers recruitment of CD11b (+) myeloid cells and reprogramming of macrophages toward the M2-phenotype [131], simultaneously increasing CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells in the TME [132]. In two recent preclinical studies, 90Y-NM600 activated the STING-IFN1 signaling pathway and increased proinflammatory cytokines [133,134]. Radionuclide therapy also enhanced infiltration of immunostimulatory CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells, APCs, NK cells, and other innate immune cells into the TME and affected TAMs and Tregs, having the potential to target TME by radioimmunotherapy [133,134,135,136]. Lutetium-177 (177Lu) is a promising therapeutic radionuclide with suitable β(-) energy and physical half-life. When targeted to mineralized bone cells, it could induce apoptotic osteosarcoma cell death while being effective for cancer bone pain palliation [137,138]. 177Lu-PSMA increased T cell infiltration into tumors and induced immunogenic cancer cell death and modulated TME, improving progression-free and overall survival in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer [139]. Phase 1 clinical trial of pretargeted radioimmunotherapy (PRIT) using GD2-specific Self-Assembling Disassembling (GD2-SADA) BsAb platform to deliver 177Lu-DOTA payload in patients with recurrent or refractory GD2(+) solid tumors including osteosarcoma is ongoing (NCT05130255) [140].

5. Combination Strategies to Overcome the Limitations of T Cell Immunotherapy against Osteosarcoma

Among the latest trends in T cell immunotherapy, various combination approaches are actively explored. First, strategies that combine ATC with ICI may encourage functional persistence of BsAb- or CAR-driven T cells in osteosarcoma. CAR or BsAb drives TILs to exert highly specific anti-tumor immune responses [62,141], which can be theoretically amplified by the addition of ICIs to reinvigorate exhausted T cells [142]. In a HER2(+) breast cancer model, HER2-CAR T cells upregulated PD-1 after incubation with target cells, and the PD-1 blockade did increase CAR T cell proliferation, IFN-γ production, and granzyme B expression in vitro while enhancing in vivo cytotoxicity [143]. The third-generation GD2-CAR T cells had highly potent immediate cytotoxicity, but significant activation-induced cell death (AICD) was observed after chronic antigen stimulation, where the PD-1 blockade enhanced GD2-CAR T cell survival and cytotoxicity against melanoma cell lines [144]. Cherkassky et al. also reported that PD-1 inhibitors rescued the effector function of exhausted mesothelin-specific CAR T cells and improved the potency of CAR T cells in a model of pleural mesothelioma [145]. However, the clinical study of GD2-CAR T cells combined with the PD-1 inhibitor failed to achieve the intended synergy; the PD-1 inhibitor did not further enhance GD2-CAR T cell expansion or persistence, laying the blame on tumor-infiltrating macrophages [74]. A phase I clinical study of HER2-CAR T cells in combination with PD-1 antibody to test safety and efficacy in patients with advanced sarcoma is ongoing (NCT04995003).

Combinations of T-BsAb and PD-1/PD-L1 blockades have also been studied. T-BsAb upregulates PD-1 on T cells and PD-L1 on tumor cells, and a combination of anti-CEA (carcinoembryonic antigen) BsAb and PD-L1 inhibitor improved anti-tumor efficacy by increasing the frequency of TILs when compared with each monotherapy in preclinical models [146]. Anti-GD2 BsAb upregulated PD-1 on T cells and PD-L1 on osteosarcoma tumor cells. Sequential combination of PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitor enhanced GD2-BsAb-driven T cell infiltration and survival of mice, and the tumor-suppressing effect was most effective when anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment was prolonged [62]. But the ATC and ICI combinations have encountered key limitations including the short half-life of ICIs, requiring multiple administrations, inconsistent tumor penetration by T cells, and the risk of systemic on-target off-tumor toxicities [142,147]. Despite these concerns, clinical trials to test the efficacy of combining ATC with ICIs are recruiting patients with ALL (NCT05310591), sarcomas (NCT04995003), or relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma (NCT04134325).

Targeting TME is another promising strategy to overcome the limitations of T cell immunotherapy, addressing both the physical barriers and immune-hostile TME of osteosarcoma [95,99,148]. The majority of CAR T cell therapies have struggled with dose-limiting toxicities and poor efficacy against solid tumors. CAR T cells could not efficiently infiltrate the TME, requiring intratumoral injection to exert tumoricidal effects [11,65], and even then unable to survive in the immunosuppressive and hypoxic TME. In addition, CAR T cells or BsAb-driven T cells themselves recruited even more MDSCs and M2 macrophages into tumors [74], compromising their own efficacy [73]. While M2 macrophages are consistently correlated with fewer TILs, lung metastasis, and poor prognosis [149,150,151], the shift from M2 to M1 phenotype induced the regression of metastatic lesions [148,152]. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) is known to restrict osteosarcoma initiation and prevent metastasis by suppressing MDSCs and M2 polarization of macrophages, as well as disrupting TAM-cancer stem cell pathways [73,153,154]. Combined therapy of GD2-CAR T cells with ATRA significantly improved anti-tumor efficacy against sarcoma xenografts [73]. Trabectedin also reprograms the TME by targeting macrophages and monocytes, thereby inhibiting osteosarcoma tumor growth and lung metastases. Trabectedin combined with the PD-1 inhibitor significantly enhanced the number of CD8(+) TILs, improving treatment efficacy against osteosarcoma [155]. MDSCs have also been shown to affect the potency of CAR T cells, where targeting tumor MDSCs by anti-Gr1, anti-GM-CSF, or anti-PD-L1 antibody has improved treatment efficacy of anti-CEA CAR T cells in colon cancers [156]. In similar studies, TME modulation has greatly improved outcomes of BsAb-based T cell immunotherapy, where anti-Gr-1, anti-Ly6G, or anti-Ly6C antibodies to deplete MDSCs or clodronate liposome or anti-CSF1R antibodies to deplete TAMs were effectively combined with GD2-EATs or HER2-EATs for treating osteosarcoma [147]. MDSC depletion facilitated EAT trafficking and infiltration into osteosarcoma, resulting in improved tumor control. Depletion of TAMs was more effective than MDSC depletion to drive T cells into tumors, inducing more potent in vivo anti-osteosarcoma response. In these studies, dexamethasone before GD2-EAT injection predominantly depleted monocytes in the blood and macrophages in tumors while promoting GD2-EAT infiltration and anti-tumor activity [147].

Besides ICI and TME modulation, targeting neovasculature is yet another potential strategy to improve the efficacy of T cell immunotherapy in osteosarcoma. Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy has been FDA approved as first-line therapy in multiple cancers including colorectal carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, ovarian carcinoma, breast cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [157,158,159]. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and ICI normalizes the vascular–immune cross-talk to potentiate cancer immunity, becoming a compelling combination strategy in clinical trials [160]. Bevacizumab has proven synergistic effects with the PD-1 inhibitor in advanced renal cell carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma [161,162], and many clinical trials are testing the efficacy of ICIs plus anti-angiogenic agents in a variety of solid cancers [50]. The addition of VEGF blockade to T-BsAb has shown promising synergy against osteosarcoma. Anti-VEGF (bevacizumab) or anti-VEGFR2 antibodies (DC101) significantly enhanced the trafficking of EATs into tumors and CD8(+) T cell infiltration, improving the in vivo anti-tumor effect. VEGF blockade normalized tumor vasculature by inducing high endothelial venules (HEVs) and increased CD8(+) TIL survival and dispersion while mitigating the immunosuppressive TME. These findings suggest that the VEGF pathway plays a key role in developing the immune-hostile TME of osteosarcoma, and targeting the VEGF/VEGFR2 pathway is an effective strategy to overcome TME and improve the clinical efficacy of T cell immunotherapy in osteosarcoma [163].

6. Conclusions

With the arrival of T cell immunotherapy, ICIs and ATC using BsAb or CAR may provide alternative options for relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma. In order to realize the true potential of T cell immunotherapy, osteosarcoma TME needs attention: a dense ECM, high densities of M2 macrophages and MDSCs, and abnormal tumor angiogenesis, which create hypoxic and acidic tumor environment that sabotage T cell immune responses. Targeting TME using the VEGF blockade, TAMs or the MDSC modulation or softening ECM may provide promising options to overcome these hurdles for T cell immunotherapy in osteosarcoma. By combining small molecule inhibitors with no cross-resistance or toxicities, curing osteosarcoma may be even possible if these strategies can be adopted upfront before tumors develop pan-resistance.

Author Contributions

J.A.P. and N.-K.V.C. wrote and revised this manuscript. Both reviewed and approved the final submitted version. J.A.P. and N.-K.V.C. wrote and revised this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from Enid A. Haupt Endowed Chair, the Robert Steel Foundation, Kids Walk for Kids with Cancer, and the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748. This work was also supported by the Inha University Research grant and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (No. 2022R1F1A1076390).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the Nai-Kong Cheung Lab, Hong Xu, Hong-fen Guo, Yi Feng, Hoa Tran, Madelyn Espinosa-Cotton, Alan Long, and Irene Cheung, for their expertise, valuable contributions, insightful discussions, and continuous support throughout this research project.

Conflicts of Interest

N.K.C. and J.A.P. both declare that this study received funding from the following institutions. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication. Both N.K.C. and J.A.P. were named as inventors on the patent of EATs filed by M.S.K. Both M.S.K. and N.K.C. have financial interest in Y-mAbs, Abpro-Labs and Eureka Therapeutics. N.K.C. reports receiving past commercial research grants from Y-mabs Therapeutics and Abpro-Labs Inc. N.K.C. was named as inventor on multiple patents filed by M.S.K., including those licensed to Ymabs Therapeutics, Biotec Pharmacon, and Abpro-labs. N.K.C. is a SAB member for Eureka Therapeutics.

References

- Luetke, A.; Meyers, P.A.; Lewis, I.; Juergens, H. Osteosarcoma treatment—Where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, A.; Ferrari, S.; Tamburini, A.; Luksch, R.; Fagioli, F.; Bacci, G.; Ferrari, C. Late effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma patients: The Italian Sarcoma Group Experience (1983–2006). Cancer 2012, 118, 5050–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakoff, M.S.; Bielack, S.S.; Meltzer, P.; Gorlick, R. Osteosarcoma: Current Treatment and a Collaborative Pathway to Success. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 3029–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coley, W.B. The Treatment of Inoperable Sarcoma by Bacterial Toxins (the Mixed Toxins of the Streptococcus erysipelas and the Bacillus prodigiosus). Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1910, 3, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, C.R.; Smeland, S.; Bauer, H.C.; Saeter, G.; Strander, H. Interferon-alpha as the only adjuvant treatment in high-grade osteosarcoma: Long term results of the Karolinska Hospital series. Acta Oncol. 2005, 44, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, P.A.; Schwartz, C.L.; Krailo, M.D.; Healey, J.H.; Bernstein, M.L.; Betcher, D.; Ferguson, W.S.; Gebhardt, M.C.; Goorin, A.M.; Harris, M.; et al. Osteosarcoma: The addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival—A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielack, S.S.; Smeland, S.; Whelan, J.S.; Marina, N.; Jovic, G.; Hook, J.M.; Krailo, M.D.; Gebhardt, M.; Papai, Z.; Meyer, J.; et al. Methotrexate, Doxorubicin, and Cisplatin (MAP) Plus Maintenance Pegylated Interferon Alfa-2b versus MAP Alone in Patients with Resectable High-Grade Osteosarcoma and Good Histologic Response to Preoperative MAP: First Results of the EURAMOS-1 Good Response Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 2279–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Ebb, D.; Meyers, P.; Grier, H.; Bernstein, M.; Gorlick, R.; Lipshultz, S.E.; Krailo, M.; Devidas, M.; Barkauskas, D.A.; Siegal, G.P.; et al. Phase II trial of trastuzumab in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy for treatment of metastatic osteosarcoma with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 overexpression: A report from the children’s oncology group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2545–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.T.; Griffith, K.A.; Zalupski, M.M.; Schuetze, S.M.; Thomas, D.G.; Lucas, D.R.; Baker, L.H.; Chugh, R. Phase II trial of cetuximab in patients with metastatic or locally advanced soft tissue or bone sarcoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 36, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, L.M.; Malempati, S.; Krailo, M.; Gao, Y.; Buxton, A.; Weigel, B.J.; Hawthorne, T.; Crowley, E.; Moscow, J.A.; Reid, J.M.; et al. Phase II trial of the glycoprotein non-metastatic B-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, glembatumumab vedotin (CDX-011), in recurrent osteosarcoma AOST1521: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 121, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Salsman, V.S.; Yvon, E.; Louis, C.U.; Perlaky, L.; Wels, W.S.; Dishop, M.K.; Kleinerman, E.E.; Pule, M.; Rooney, C.M.; et al. Immunotherapy for osteosarcoma: Genetic modification of T cells overcomes low levels of tumor antigen expression. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 1779–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.L.; Uttenreuther-Fischer, M.M.; Huang, C.S.; Tsui, C.C.; Gillies, S.D.; Reisfeld, R.A.; Kung, F.H. Phase I trial of a human-mouse chimeric anti-disialoganglioside monoclonal antibody ch14.18 in patients with refractory neuroblastoma and osteosarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 2169–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, M.; Dvorkin, M.; Laktionov, K.K.; Navarro, A.; Juan-Vidal, O.; Kozlov, V.; Golden, G.; Jordan, O.; Deng, C. The anti-disialoganglioside (GD2) antibody dinutuximab (D) for second-line treatment (2LT) of patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory small cell lung cancer (RR SCLC): Results from part II of the open-label, randomized, phase II/III distinct study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, S.; Jacot, W.; Yamashita, T.; Sohn, J.; Vidal, M.; Tokunaga, E.; Tsurutani, J.; Ueno, N.T.; Prat, A.; Chae, Y.S.; et al. Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Low Advanced Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, D.R.; Janeway, K.A.; Minard, C.G.; Hall, D.; Crompton, B.D.; Lazar, A.J.; Wang, W.-L.; Voss, S.D.; Militano, O.; Gorlick, R.G.; et al. PEPN1924, a phase 2 study of trastuzumab deruxtecan (DS-8201a, T-DXd) in adolescents and young adults with recurrent HER2+ osteosarcoma: A children’s oncology group pediatric early-phase clinical Trial Network study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 11527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, D.L.; Wherry, E.J.; Masopust, D.; Zhu, B.; Allison, J.P.; Sharpe, A.H.; Freeman, G.J.; Ahmed, R. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature 2006, 439, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, L.; Janbazian, L.; Chomont, N.; Said, E.A.; Gimmig, S.; Bessette, B.; Boulassel, M.R.; Delwart, E.; Sepulveda, H.; Balderas, R.S.; et al. Upregulation of PD-1 expression on HIV-specific CD8+ T cells leads to reversible immune dysfunction. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.L.; Kaufmann, D.E.; Kiepiela, P.; Brown, J.A.; Moodley, E.S.; Reddy, S.; Mackey, E.W.; Miller, J.D.; Leslie, A.J.; DePierres, C.; et al. PD-1 expression on HIV-specific T cells is associated with T-cell exhaustion and disease progression. Nature 2006, 443, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbani, S.; Amadei, B.; Tola, D.; Massari, M.; Schivazappa, S.; Missale, G.; Ferrari, C. PD-1 expression in acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is associated with HCV-specific CD8 exhaustion. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 11398–11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Strome, S.E.; Salomao, D.R.; Tamura, H.; Hirano, F.; Flies, D.B.; Roche, P.C.; Lu, J.; Zhu, G.; Tamada, K.; et al. Tumor-associated B7-H1 promotes T-cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Schreiber, R.D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.N.; Scheper, W.; Kvistborg, P. Cancer Neoantigens. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 37, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacohen, N.; Fritsch, E.F.; Carter, T.A.; Lander, E.S.; Wu, C.J. Getting personal with neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Champiat, S.; Ferte, C.; Lebel-Binay, S.; Eggermont, A.; Soria, J.C. Exomics and immunogenics: Bridging mutational load and immune checkpoints efficacy. Oncoimmunology 2014, 3, e27817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, K.W.; Goldberg, M.S.; Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; D’Andrea, A.D. DNA Damage and Repair Biomarkers of Immunotherapy Response. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, T.; Tagami, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Uede, T.; Shimizu, J.; Sakaguchi, N.; Mak, T.W.; Sakaguchi, S. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowshanravan, B.; Halliday, N.; Sansom, D.M. CTLA-4: A moving target in immunotherapy. Blood 2018, 131, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, M.K.; Postow, M.A.; Wolchok, J.D. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Pathway Blockade: Combinations in the Clinic. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.A.; Cheung, N.V. Limitations and opportunities for immune checkpoint inhibitors in pediatric malignancies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2017, 58, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, D.R.; Krummel, M.F.; Allison, J.P. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science 1996, 271, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmerini, E.; Agostinelli, C.; Picci, P.; Pileri, S.; Marafioti, T.; Lollini, P.L.; Scotlandi, K.; Longhi, A.; Benassi, M.S.; Ferrari, S. Tumoral immune-infiltrate (IF), PD-L1 expression and role of CD8/TIA-1 lymphocytes in localized osteosarcoma patients treated within protocol ISG-OS1. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 111836–111846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Okamoto, M.; Sasaki, J.; Kuroda, C.; Ishida, H.; Ueda, K.; Okano, S.; Ideta, H.; Kamanaka, T.; Sobajima, A.; et al. Clinical outcome of osteosarcoma and its correlation with programmed death-ligand 1 and T cell activation markers. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 2513–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Ji, B. Evidence of Interleukin 21 Reduction in Osteosarcoma Patients Due to PD-1/PD-L1-Mediated Suppression of Follicular Helper T Cell Functionality. DNA Cell Biol. 2017, 36, 794–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.J.; Kong, D.L. PD-L1/PD-1 axis serves an important role in natural killer cell-induced cytotoxicity in osteosarcoma. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 2049–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, P.; Roth, M.E.; Gill, J.; Piperdi, S.; Chinai, J.M.; Geller, D.S.; Hoang, B.H.; Park, A.; Fremed, M.A.; Zang, X.; et al. Immune infiltration and PD-L1 expression in the tumor microenvironment are prognostic in osteosarcoma. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 30093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, D.; Wu, F.; Zhong, B.; Shao, Z. Prognostic Value of Programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand-1 (PD-L1) or PD-1 Expression in Patients with Osteosarcoma: A Meta-Analysis. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 2525–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.K.; Cote, G.M.; Choy, E.; Yang, P.; Harmon, D.; Schwab, J.; Nielsen, G.P.; Chebib, I.; Ferrone, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Chen, L.; Feng, Y.; Shen, J.; Gao, Y.; Cote, G.; Choy, E.; Harmon, D.; Mankin, H.; Hornicek, F.; et al. Targeting programmed cell death ligand 1 by CRISPR/Cas9 in osteosarcoma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 30276–30287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, D.M.; O’Neill, L.; Nieves, L.M.; McAfee, M.S.; Holechek, S.A.; Collins, A.W.; Dickman, P.; Jacobsen, J.; Hingorani, P.; Blattman, J.N. Enhanced T-cell immunity to osteosarcoma through antibody blockade of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions. J. Immunother. 2015, 38, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Fuchimoto, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Okita, H.; Kitagawa, Y.; Kuroda, T. The effect of immune checkpoint inhibitors on lung metastases of osteosarcoma. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 52, 2047–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Sun, K.; Wang, S.; Bao, X.; Liu, K.; Guo, W. PD-1 axis expression in musculoskeletal tumors and antitumor effect of nivolumab in osteosarcoma model of humanized mouse. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, M.S.; Wright, M.; Baird, K.; Wexler, L.H.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Bernstein, D.; Delbrook, C.; Lodish, M.; Bishop, R.; Wolchok, J.D.; et al. Phase I Clinical Trial of Ipilimumab in Pediatric Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 1364–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawbi, H.A.; Burgess, M.; Bolejack, V.; Van Tine, B.A.; Schuetze, S.M.; Hu, J.; D’Angelo, S.; Attia, S.; Riedel, R.F.; Priebat, D.A.; et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma and bone sarcoma (SARC028): A multicentre, two-cohort, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boye, K.; Longhi, A.; Guren, T.; Lorenz, S.; Naess, S.; Pierini, M.; Taksdal, I.; Lobmaier, I.; Cesari, M.; Paioli, A.; et al. Pembrolizumab in advanced osteosarcoma: Results of a single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussier, D.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Hingorani, P.; Blattman, J.N. Combination immunotherapy with alpha-CTLA-4 and alpha-PD-L1 antibody blockade prevents immune escape and leads to complete control of metastatic osteosarcoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2015, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.P.; Mahoney, M.R.; Van Tine, B.A.; Atkins, J.; Milhem, M.M.; Jahagirdar, B.N.; Antonescu, C.R.; Horvath, E.; Tap, W.D.; Schwartz, G.K.; et al. Nivolumab with or without ipilimumab treatment for metastatic sarcoma (Alliance A091401): Two open-label, non-comparative, randomised, phase 2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somaiah, N.; Conley, A.P.; Parra, E.R.; Lin, H.; Amini, B.; Solis Soto, L.; Salazar, R.; Barreto, C.; Chen, H.; Gite, S.; et al. Durvalumab plus tremelimumab in advanced or metastatic soft tissue and bone sarcomas: A single-centre phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterz, U.; Grube, M.; Herr, W.; Menhart, K.; Wendl, C.; Vogelhuber, M. Case Report: Dual Checkpoint Inhibition in Advanced Metastatic Osteosarcoma Results in Remission of All Tumor Manifestations-A Report of a Stunning Success in a 37-Year-Old Patient. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 684733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuytemans, L.; Sys, G.; Creytens, D.; Lapeire, L. NGS-analysis to the rescue: Dual checkpoint inhibition in metastatic osteosarcoma—A case report and review of the literature. Acta Clin. Belg. 2021, 76, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Xu, J.; Sun, X.; Guo, W.; Gu, J.; Liu, K.; Zheng, B.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Apatinib plus camrelizumab (anti-PD1 therapy, SHR-1210) for advanced osteosarcoma (APFAO) progressing after chemotherapy: A single-arm, open-label, phase 2 trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e000798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keung, E.Z.; Lazar, A.J.; Torres, K.E.; Wang, W.L.; Cormier, J.N.; Ashleigh Guadagnolo, B.; Bishop, A.J.; Lin, H.; Hunt, K.K.; Bird, J.; et al. Phase II study of neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade in patients with surgically resectable undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.L.; Fox, E.; Merchant, M.S.; Reid, J.M.; Kudgus, R.A.; Liu, X.; Minard, C.G.; Voss, S.; Berg, S.L.; Weigel, B.J.; et al. Nivolumab in children and young adults with relapsed or refractory solid tumours or lymphoma (ADVL1412): A multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geoerger, B.; Zwaan, C.M.; Marshall, L.V.; Michon, J.; Bourdeaut, F.; Casanova, M.; Corradini, N.; Rossato, G.; Farid-Kapadia, M.; Shemesh, C.S.; et al. Atezolizumab for children and young adults with previously treated solid tumours, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and Hodgkin lymphoma (iMATRIX): A multicentre phase 1-2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Broto, J.; Hindi, N.; Grignani, G.; Martinez-Trufero, J.; Redondo, A.; Valverde, C.; Stacchiotti, S.; Lopez-Pousa, A.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Gutierrez, A.; et al. Nivolumab and sunitinib combination in advanced soft tissue sarcomas: A multicenter, single-arm, phase Ib/II trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8, e001561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, G.L.; O’Hara, M. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the treatment of solid tumors: Defining the challenges and next steps. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 166, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewski, T.F. Failure at the effector phase: Immune barriers at the level of the melanoma tumor microenvironment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 5256–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, E.K.; Wang, L.C.; Dolfi, D.V.; Wilson, C.B.; Ranganathan, R.; Sun, J.; Kapoor, V.; Scholler, J.; Pure, E.; Milone, M.C.; et al. Multifactorial T-cell hypofunction that is reversible can limit the efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor-transduced human T cells in solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4262–4273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gust, J.; Hay, K.A.; Hanafi, L.A.; Li, D.; Myerson, D.; Gonzalez-Cuyar, L.F.; Yeung, C.; Liles, W.C.; Wurfel, M.; Lopez, J.A.; et al. Endothelial Activation and Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Neurotoxicity after Adoptive Immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T Cells. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1404–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Wu, Z.; Luo, W. Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-Cell Therapy: The Light of Day for Osteosarcoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Simayi, N.; Wan, R.; Huang, W. CAR T targets and microenvironmental barriers of osteosarcoma. Cytotherapy 2022, 24, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Zan, P.; Sun, M.; Wang, C.; et al. Inhibition of sphingolipid metabolism in osteosarcoma protects against CD151-mediated tumorigenicity. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.A.; Cheung, N.V. GD2 or HER2 targeting T cell engaging bispecific antibodies to treat osteosarcoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, H.; Muller, E.; Inderberg, E.M.; Bruland, O.; Walchli, S. Treating osteosarcoma with CAR T cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 2019, 89, e12741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Brawley, V.S.; Hegde, M.; Robertson, C.; Ghazi, A.; Gerken, C.; Liu, E.; Dakhova, O.; Ashoori, A.; Corder, A.; et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2)-Specific Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Modified T Cells for the Immunotherapy of HER2-Positive Sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1688–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainusso, N.; Brawley, V.S.; Ghazi, A.; Hicks, M.J.; Gottschalk, S.; Rosen, J.M.; Ahmed, N. Immunotherapy targeting HER2 with genetically modified T cells eliminates tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012, 19, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chulanetra, M.; Morchang, A.; Sayour, E.; Eldjerou, L.; Milner, R.; Lagmay, J.; Cascio, M.; Stover, B.; Slayton, W.; Chaicumpa, W.; et al. GD2 chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells in synergy with sub-toxic level of doxorubicin targeting osteosarcomas. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2020, 10, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Majzner, R.G.; Theruvath, J.L.; Nellan, A.; Heitzeneder, S.; Cui, Y.; Mount, C.W.; Rietberg, S.P.; Linde, M.H.; Xu, P.; Rota, C.; et al. CAR T Cells Targeting B7-H3, a Pan-Cancer Antigen, Demonstrate Potent Preclinical Activity against Pediatric Solid Tumors and Brain Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2560–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers, G.R.; Ho, M.; Zielenska, M.; Squire, J.A.; Thorner, P.S. HER2 amplification and overexpression is not present in pediatric osteosarcoma: A tissue microarray study. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol. 2005, 8, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navai, S.A.; Derenzo, C.; Joseph, S.; Sanber, K.; Byrd, T.; Zhang, H.M.; Mata, M.; Gerken, C.; Shree, A.; Mathew, P.R.; et al. Administration of HER2-CAR T cells after lymphodepletion safely improves T cell expansion and induces clinical responses in patients with advanced sarcomas. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, LB-147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.; Linkowski, M.; Tarim, J.; Piperdi, S.; Sowers, R.; Geller, D.; Gill, J.; Gorlick, R. Ganglioside GD2 as a therapeutic target for antibody-mediated therapy in patients with osteosarcoma. Cancer 2014, 120, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, V.I.; Roth, M.; Piperdi, S.; Geller, D.; Gill, J.; Rudzinski, E.R.; Hawkins, D.S.; Gorlick, R. Ganglioside GD2 expression is maintained upon recurrence in patients with osteosarcoma. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2015, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, H.; Hamamura, K.; Hotta, H.; Matsumoto, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Hattori, H.; Furukawa, K.; Ueda, M.; Furukawa, K. Enhancement of malignant properties of human osteosarcoma cells with disialyl gangliosides GD2/GD3. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.H.; Highfill, S.L.; Cui, Y.; Smith, J.P.; Walker, A.J.; Ramakrishna, S.; El-Etriby, R.; Galli, S.; Tsokos, M.G.; Orentas, R.J.; et al. Reduction of MDSCs with All-trans Retinoic Acid Improves CAR Therapy Efficacy for Sarcomas. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016, 4, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heczey, A.; Louis, C.U.; Savoldo, B.; Dakhova, O.; Durett, A.; Grilley, B.; Liu, H.; Wu, M.F.; Mei, Z.; Gee, A.; et al. CAR T Cells Administered in Combination with Lymphodepletion and PD-1 Inhibition to Patients with Neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 2017, 25, 2214–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Bufalo, F.; De Angelis, B.; Caruana, I.; Del Baldo, G.; De Ioris, M.A.; Serra, A.; Mastronuzzi, A.; Cefalo, M.G.; Pagliara, D.; Amicucci, M.; et al. GD2-CART01 for Relapsed or Refractory High-Risk Neuroblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, W.; Shan, B.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, G.; Cao, N.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. B7-H3 is overexpressed in patients suffering osteosarcoma and associated with tumor aggressiveness and metastasis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modak, S.; Kramer, K.; Gultekin, S.H.; Guo, H.F.; Cheung, N.K. Monoclonal antibody 8H9 targets a novel cell surface antigen expressed by a wide spectrum of human solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4048–4054. [Google Scholar]

- Picarda, E.; Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Zang, X. Molecular Pathways: Targeting B7-H3 (CD276) for Human Cancer Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3425–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, L.; Somovilla-Crespo, B.; Garcia-Rodriguez, P.; Morales-Molina, A.; Rodriguez-Milla, M.A.; Garcia-Castro, J. Switchable CAR T cell strategy against osteosarcoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 2623–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przepiorka, D.; Ko, C.W.; Deisseroth, A.; Yancey, C.L.; Candau-Chacon, R.; Chiu, H.J.; Gehrke, B.J.; Gomez-Broughton, C.; Kane, R.C.; Kirshner, S.; et al. FDA Approval: Blinatumomab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 4035–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarjian, H.; Stein, A.; Gokbuget, N.; Fielding, A.K.; Schuh, A.C.; Ribera, J.M.; Wei, A.; Dombret, H.; Foa, R.; Bassan, R.; et al. Blinatumomab versus Chemotherapy for Advanced Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 836–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiss, M.M.; Murawa, P.; Koralewski, P.; Kutarska, E.; Kolesnik, O.O.; Ivanchenko, V.V.; Dudnichenko, A.S.; Aleknaviciene, B.; Razbadauskas, A.; Gore, M.; et al. The trifunctional antibody catumaxomab for the treatment of malignant ascites due to epithelial cancer: Results of a prospective randomized phase II/III trial. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 2209–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knodler, M.; Korfer, J.; Kunzmann, V.; Trojan, J.; Daum, S.; Schenk, M.; Kullmann, F.; Schroll, S.; Behringer, D.; Stahl, M.; et al. Randomised phase II trial to investigate catumaxomab (anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3) for treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis in patients with gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 119, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burges, A.; Wimberger, P.; Kumper, C.; Gorbounova, V.; Sommer, H.; Schmalfeldt, B.; Pfisterer, J.; Lichinitser, M.; Makhson, A.; Moiseyenko, V.; et al. Effective relief of malignant ascites in patients with advanced ovarian cancer by a trifunctional anti-EpCAM × anti-CD3 antibody: A phase I/II study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 3899–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lum, L.G.; Thakur, A.; Al-Kadhimi, Z.; Colvin, G.A.; Cummings, F.J.; Legare, R.D.; Dizon, D.S.; Kouttab, N.; Maizel, A.; Colaiace, W.; et al. Targeted T-cell Therapy in Stage IV Breast Cancer: A Phase I Clinical Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankelevich, M.; Kondadasula, S.V.; Thakur, A.; Buck, S.; Cheung, N.K.; Lum, L.G. Anti-CD3 × anti-GD2 bispecific antibody redirects T-cell cytolytic activity to neuroblastoma targets. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2012, 59, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusch, U.; Sundaram, M.; Davol, P.A.; Olson, S.D.; Davis, J.B.; Demel, K.; Nissim, J.; Rathore, R.; Liu, P.Y.; Lum, L.G. Anti-CD3 × anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) bispecific antibody redirects T-cell cytolytic activity to EGFR-positive cancers in vitro and in an animal model. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishampayan, U.; Thakur, A.; Rathore, R.; Kouttab, N.; Lum, L.G. Phase I Study of Anti-CD3 × Anti-Her2 Bispecific Antibody in Metastatic Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer Patients. Prostate Cancer 2015, 2015, 285193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yankelevich, M.; Modak, S.; Chu, R.; Lee, D.W.; Thakur, A.; Cheung, N.-K.V.; Lum, L.G. Phase I study of OKT3 × hu3F8 bispecific antibody (GD2Bi) armed T cells (GD2BATs) in GD2-positive tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. S15), 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santich, B.H.; Park, J.A.; Tran, H.; Guo, H.F.; Huse, M.; Cheung, N.V. Interdomain spacing and spatial configuration drive the potency of IgG-[L]-scFv T cell bispecific antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaax1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.A.; Santich, B.H.; Xu, H.; Lum, L.G.; Cheung, N.V. Potent ex vivo armed T cells using recombinant bispecific antibodies for adoptive immunotherapy with reduced cytokine release. J. Immunother. Cancer 2021, 9, e002222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Tashiro, H.; Omer, B.; Lapteva, N.; Ando, J.; Ngo, M.; Mehta, B.; Dotti, G.; Kinchington, P.R.; Leen, A.M.; et al. Vaccination Targeting Native Receptors to Enhance the Function and Proliferation of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-Modified T Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, T.; Zheng, L.; Liu, H.; Song, W.; Liu, D.; Li, Z.; Pan, C.X. Combination strategies to maximize the benefits of cancer immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Tan, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, H.; Yuan, H. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in osteosarcoma: A hopeful and challenging future. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1031527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corre, I.; Verrecchia, F.; Crenn, V.; Redini, F.; Trichet, V. The Osteosarcoma Microenvironment: A Complex But Targetable Ecosystem. Cells 2020, 9, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfranca, A.; Martinez-Cruzado, L.; Tornin, J.; Abarrategi, A.; Amaral, T.; de Alava, E.; Menendez, P.; Garcia-Castro, J.; Rodriguez, R. Bone microenvironment signals in osteosarcoma development. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3097–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verrecchia, F.; Redini, F. Transforming Growth Factor-beta Signaling Plays a Pivotal Role in the Interplay between Osteosarcoma Cells and Their Microenvironment. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, G.; Chen, R.; Hua, Y.; Cai, Z. Mesenchymal stem cells in the osteosarcoma microenvironment: Their biological properties, influence on tumor growth, and therapeutic implications. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Han, J.; Yang, L.; Cai, Z.; Sun, W.; Hua, Y.; Xu, J. Immune Microenvironment in Osteosarcoma: Components, Therapeutic Strategies and Clinical Applications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolb, A.D.; Bussard, K.M. The Bone Extracellular Matrix as an Ideal Milieu for Cancer Cell Metastases. Cancers 2019, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, P.; Wei, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: New mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol. Cancer 2020, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Dean, D.; Hornicek, F.J.; Chen, Z.; Duan, Z. The role of extracelluar matrix in osteosarcoma progression and metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.P.; Martin, J.D.; Liu, H.; Lacorre, D.A.; Jain, S.R.; Kozin, S.V.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Mousa, A.S.; Han, X.; Adstamongkonkul, P.; et al. Angiotensin inhibition enhances drug delivery and potentiates chemotherapy by decompressing tumour blood vessels. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diop-Frimpong, B.; Chauhan, V.P.; Krane, S.; Boucher, Y.; Jain, R.K. Losartan inhibits collagen I synthesis and improves the distribution and efficacy of nanotherapeutics in tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 2909–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Cao, J.; Melamed, A.; Worley, M.; Gockley, A.; Jones, D.; Nia, H.T.; Zhang, Y.; Stylianopoulos, T.; Kumar, A.S.; et al. Losartan treatment enhances chemotherapy efficacy and reduces ascites in ovarian cancer models by normalizing the tumor stroma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2210–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, D.P.; Chow, L.; Das, S.; Haines, L.; Palmer, E.; Kurihara, J.N.; Coy, J.W.; Mathias, A.; Thamm, D.H.; Gustafson, D.L.; et al. Losartan Blocks Osteosarcoma-Elicited Monocyte Recruitment, and Combined with the Kinase Inhibitor Toceranib, Exerts Significant Clinical Benefit in Canine Metastatic Osteosarcoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburg, O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956, 123, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppenol, W.H.; Bounds, P.L.; Dang, C.V. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.Y.; Tsai, H.C.; Chou, P.Y.; Wang, S.W.; Chen, H.T.; Lin, Y.M.; Chiang, I.P.; Chang, T.M.; Hsu, S.K.; Chou, M.C.; et al. CCL3 promotes angiogenesis by dysregulation of miR-374b/ VEGF-A axis in human osteosarcoma cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 4310–4325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.W.; Liu, S.C.; Sun, H.L.; Huang, T.Y.; Chan, C.H.; Yang, C.Y.; Yeh, H.I.; Huang, Y.L.; Chou, W.Y.; Lin, Y.M.; et al. CCL5/CCR5 axis induces vascular endothelial growth factor-mediated tumor angiogenesis in human osteosarcoma microenvironment. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.H.; Tsai, H.C.; Cheng, Y.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Huang, Y.L.; Tsai, C.H.; Xu, G.H.; Wang, S.W.; Fong, Y.C.; Tang, C.H. CTGF promotes osteosarcoma angiogenesis by regulating miR-543/angiopoietin 2 signaling. Cancer Lett. 2017, 391, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohba, T.; Cates, J.M.; Cole, H.A.; Slosky, D.A.; Haro, H.; Ando, T.; Schwartz, H.S.; Schoenecker, J.G. Autocrine VEGF/VEGFR1 signaling in a subpopulation of cells associates with aggressive osteosarcoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Dai, R.; Xu, J.; Feng, H. Transferrin receptor-1 and VEGF are prognostic factors for osteosarcoma. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019, 14, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Yu, H.; Krygier, J.E.; Wooley, P.H.; Mott, M.P. High VEGF with rapid growth and early metastasis in a mouse osteosarcoma model. Sarcoma 2007, 2007, 95628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Ji, Z.; Li, D.; Dong, Q. Proliferation inhibition and apoptosis promotion by dual silencing of VEGF and Survivin in human osteosarcoma. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2019, 51, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Bruni, D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, Y.; Hookway, E.; Williams, K.A.; Hassan, A.B.; Oppermann, U.; Tanaka, Y.; Soilleux, E.; Athanasou, N.A. Dendritic and mast cell involvement in the inflammatory response to primary malignant bone tumours. Clin. Sarcoma Res. 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Liang, X.; Ren, T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, W.; Niu, J.; Lou, J.; et al. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in osteosarcoma progression—Therapeutic implications. Cell Oncol. 2021, 44, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl, S.M.; Pallud, C.; Beuvon, F.; Hacene, K.; Stanley, E.R.; Rohrschneider, L.; Tang, R.; Pouillart, P.; Lidereau, R. Anti-colony-stimulating factor-1 antibody staining in primary breast adenocarcinomas correlates with marked inflammatory cell infiltrates and prognosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994, 86, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Geng, X.; Hou, J.; Wu, G. New insights into M1/M2 macrophages: Key modulators in cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Xu, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhu, X.; Chen, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, G.; Song, Y.; Song, G.; Lu, J.; et al. Reprograming the tumor immunologic microenvironment using neoadjuvant chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab, M.; Rostalski, T.; Lee, K.H.; Mogler, C.; Augustin, H.G. Tie2 Receptor in Tumor-Infiltrating Macrophages Is Dispensable for Tumor Angiogenesis and Tumor Relapse after Chemotherapy. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. Targeting macrophages: Therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Cao, J.; Li, B.; Nice, E.C.; Mao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C. Managing the immune microenvironment of osteosarcoma: The outlook for osteosarcoma treatment. Bone Res. 2023, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, J. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: The dawn of cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, M.; Patin, E.C.; Pedersen, M.; Wilkins, A.; Dillon, M.T.; Melcher, A.A.; Harrington, K.J. Inflammatory microenvironment remodelling by tumour cells after radiotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Zubiaurre, I.; Chalmers, A.J.; Hellevik, T. Radiation-Induced Transformation of Immunoregulatory Networks in the Tumor Stroma. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.S.; Chen, F.H.; Wang, C.C.; Huang, H.L.; Jung, S.M.; Wu, C.J.; Lee, C.C.; McBride, W.H.; Chiang, C.S.; Hong, J.H. Macrophages from irradiated tumors express higher levels of iNOS, arginase-I and COX-2, and promote tumor growth. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2007, 68, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, F.; Meng, X.; Kong, L.; Mu, D.; Zhu, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, forkhead box P3, programmed death ligand-1, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 expressions before and after neoadjuvant chemoradiation in rectal cancer. Transl. Res. 2015, 166, 721–732.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodinsky, J.C.; Jin, W.J.; Bates, A.M.; Hernandez, R.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Marsh, I.R.; Chakravarty, I.; Arthur, I.S.; Zangl, L.M.; Brown, R.J.; et al. Temporal analysis of type 1 interferon activation in tumor cells following external beam radiotherapy or targeted radionuclide therapy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6120–6137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.B.; Hernandez, R.; Carlson, P.; Grudzinski, J.; Bates, A.M.; Jagodinsky, J.C.; Erbe, A.; Marsh, I.R.; Arthur, I.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; et al. Low-dose targeted radionuclide therapy renders immunologically cold tumors responsive to immune checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabb3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, R.; Walker, K.L.; Grudzinski, J.J.; Aluicio-Sarduy, E.; Patel, R.; Zahm, C.D.; Pinchuk, A.N.; Massey, C.F.; Bitton, A.N.; Brown, R.J.; et al. (90)Y-NM600 targeted radionuclide therapy induces immunologic memory in syngeneic models of T-cell Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vito, A.; Rathmann, S.; Mercanti, N.; El-Sayes, N.; Mossman, K.; Valliant, J. Combined Radionuclide Therapy and Immunotherapy for Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, C.; Vats, K.; Lohar, S.P.; Korde, A.; Samuel, G. Camptothecin Enhances Cell Death Induced by (177)Lu-EDTMP in Osteosarcoma Cells. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2014, 29, 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Alavi, M.; Omidvari, S.; Mehdizadeh, A.; Jalilian, A.R.; Bahrami-Samani, A. Metastatic Bone Pain Palliation Using (177)Lu-Ethylenediaminetetramethylene Phosphonic Acid. World J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 14, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, G.; Able, S.; Skaripa-Koukelli, I.; Anderson, R.; Wilson, G.; Vallis, K.A. Evaluation of anti-tumor immunity in response to [177Lu]Lu-PSMA in a mouse model of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taofeek, K.; Owonikoko, J.C.M.; Yoon, J.; Slotkin, E.K.; Dowlati, A.; Ma, V.T.; Düring, M.; Sveistrup, J. Phase 1 trial of GD2-SADA:177Lu-DOTA drug complex in patients with recurrent or refractory metastatic solid tumors known to express GD2 including small cell lung cancer (SCLC), sarcoma, and malignant melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, TPS3162. [Google Scholar]

- Adusumilli, P.S.; Cherkassky, L.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Colovos, C.; Servais, E.; Plotkin, J.; Jones, D.R.; Sadelain, M. Regional delivery of mesothelin-targeted CAR T cell therapy generates potent and long-lasting CD4-dependent tumor immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 261ra151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosser, R.; Cherkassky, L.; Chintala, N.; Adusumilli, P.S. Combination Immunotherapy with CAR T Cells and Checkpoint Blockade for the Treatment of Solid Tumors. Cancer Cell 2019, 36, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, L.B.; Devaud, C.; Duong, C.P.; Yong, C.S.; Beavis, P.A.; Haynes, N.M.; Chow, M.T.; Smyth, M.J.; Kershaw, M.H.; Darcy, P.K. Anti-PD-1 antibody therapy potently enhances the eradication of established tumors by gene-modified T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5636–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargett, T.; Yu, W.; Dotti, G.; Yvon, E.S.; Christo, S.N.; Hayball, J.D.; Lewis, I.D.; Brenner, M.K.; Brown, M.P. GD2-specific CAR T Cells Undergo Potent Activation and Deletion Following Antigen Encounter but Can Be Protected from Activation-induced Cell Death by PD-1 Blockade. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkassky, L.; Morello, A.; Villena-Vargas, J.; Feng, Y.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Jones, D.R.; Sadelain, M.; Adusumilli, P.S. Human CAR T cells with cell-intrinsic PD-1 checkpoint blockade resist tumor-mediated inhibition. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3130–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, J.; Colombetti, S.; Fauti, T.; Roller, A.; Biehl, M.; Fahrni, L.; Nicolini, V.; Perro, M.; Nayak, T.; Bommer, E.; et al. Combination of T-Cell Bispecific Antibodies with PD-L1 Checkpoint Inhibition Elicits Superior Anti-Tumor Activity. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 575737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.A.; Wang, L.; Cheung, N.V. Modulating tumor infiltrating myeloid cells to enhance bispecific antibody-driven T cell infiltration and anti-tumor response. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2021, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Kang, Y.; Liao, Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, C. Novel Immunotherapies for Osteosarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 830546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]