Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

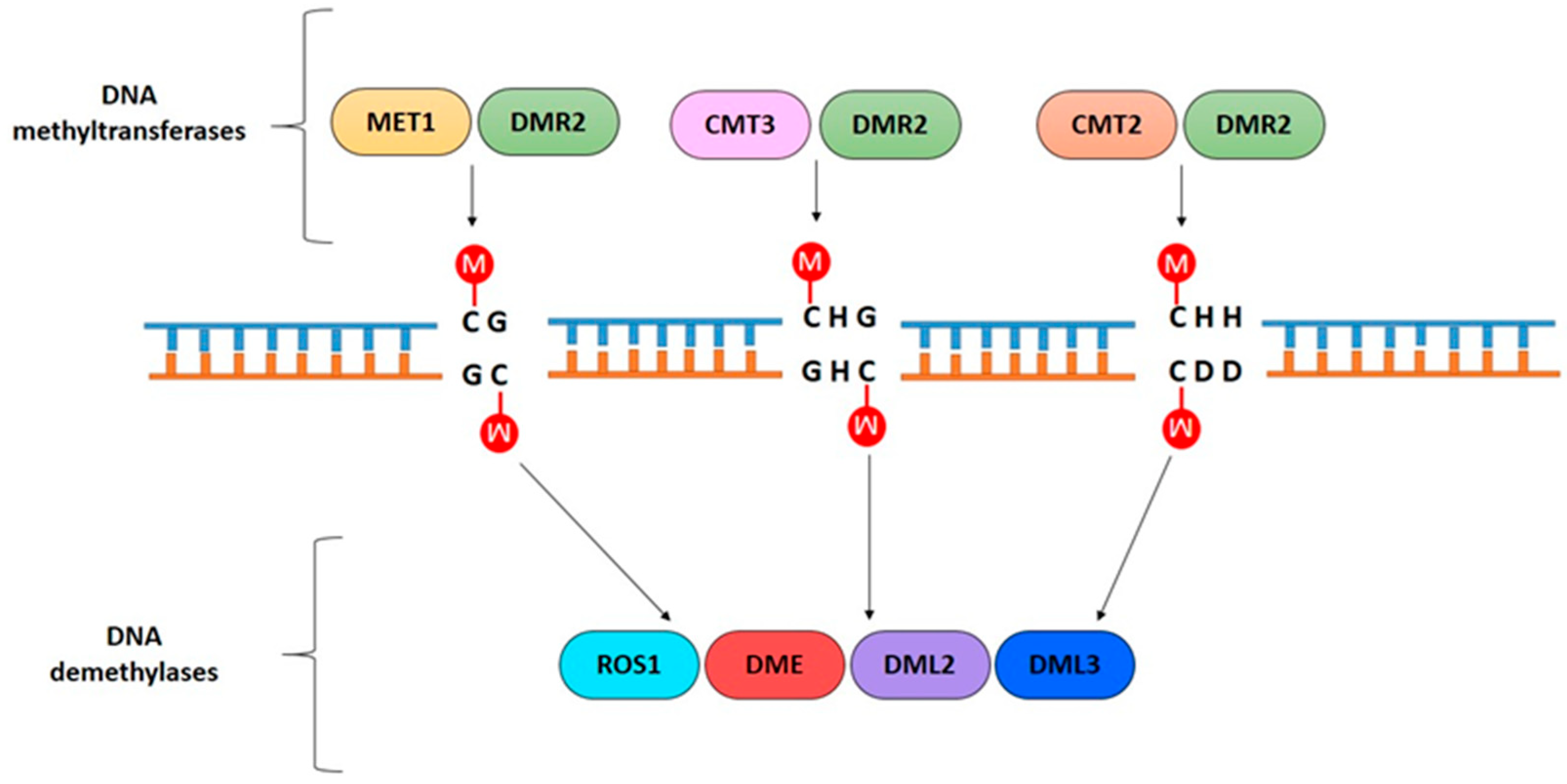

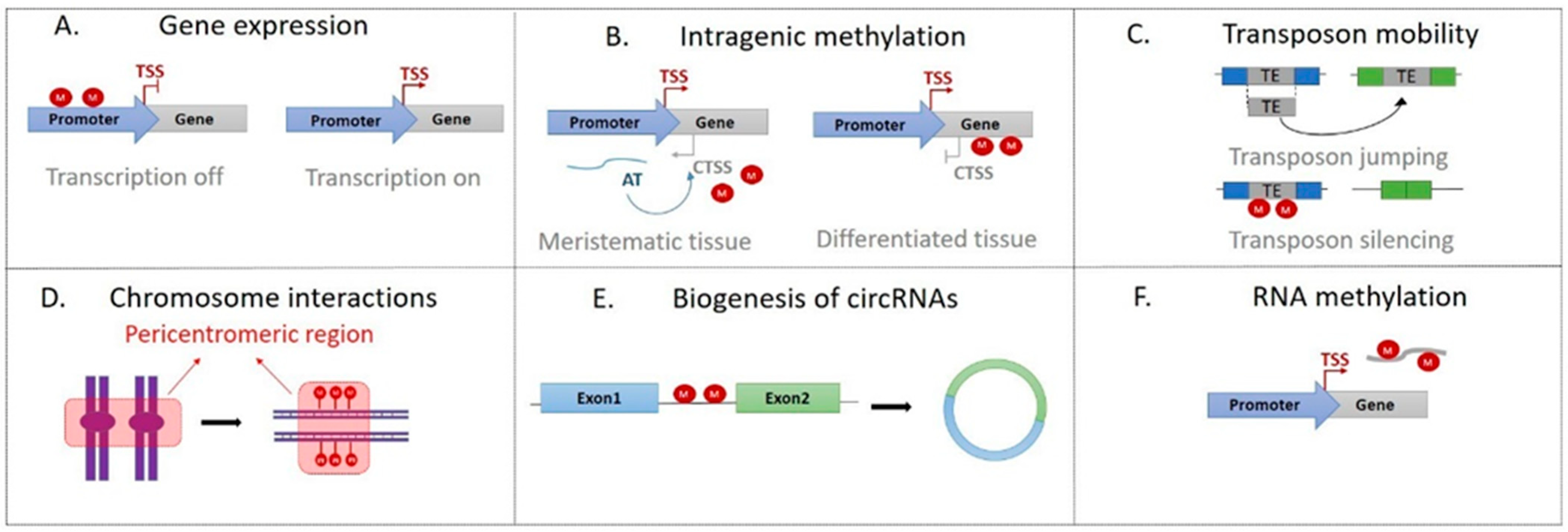

2. Role of DNA Methylation in Plant Cells

2.1. Gene Expression

2.2. Transposon Mobility

2.3. Chromosome Interactions

2.4. Biogenesis of circRNAs

2.5. RNA Methylation

3. DNA Methylation during Plant Development

3.1. Genomic Imprinting

3.2. Floral Pigmentation, Floral Scent, and Photosynthesis

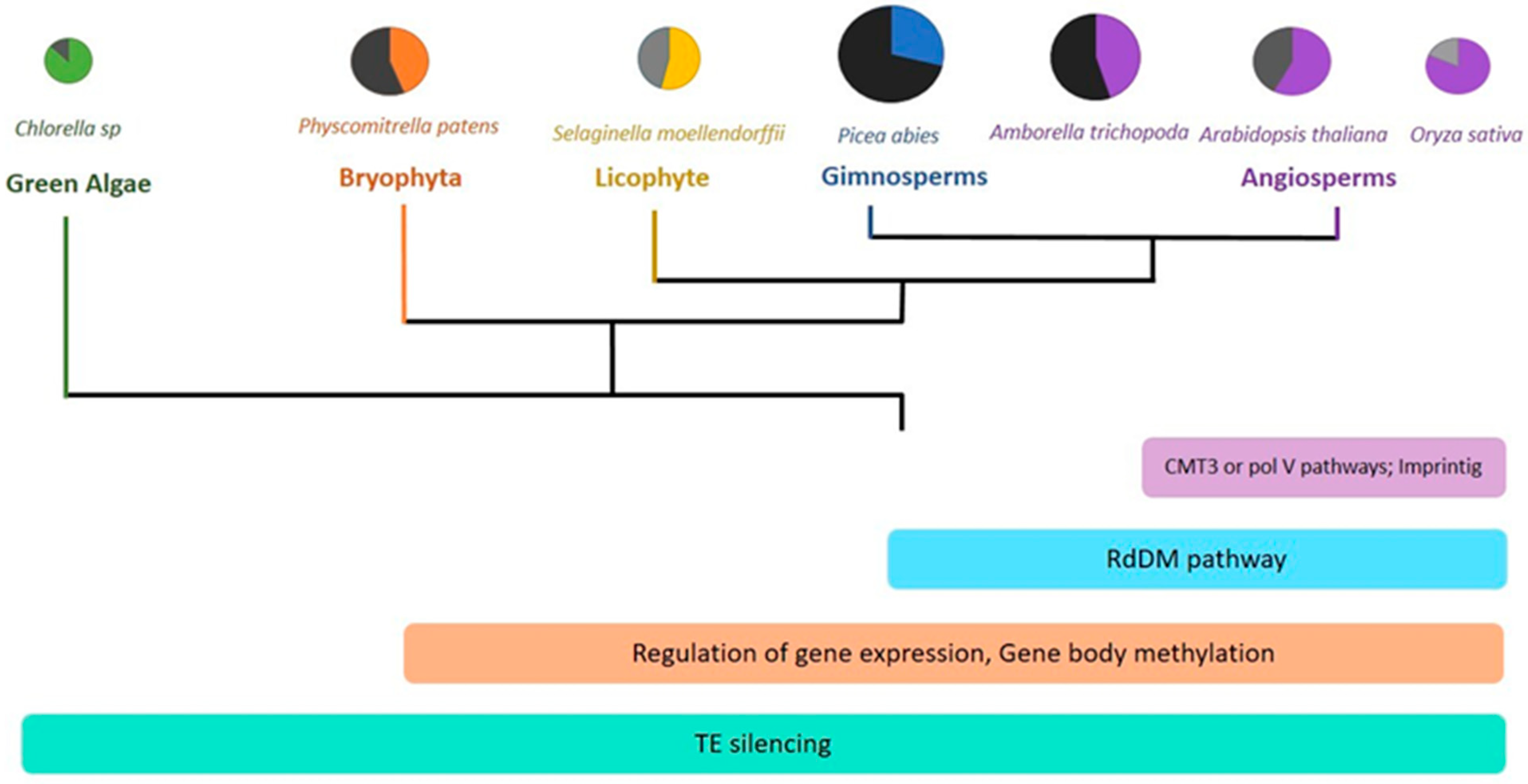

4. Methylation, Environment, and Evolution

4.1. Abiotic and Biotic Stimuli

4.2. Environmental Adaptations and Evolution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berger, S.L.; Kouzarides, T.; Shiekhattar, R.; Shilatifard, A. An operational definition of epigenetics. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, I.R.; Jacobsen, S.E. Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 2007, 447, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeji, H.; Nishimura, T. Epigenetic Mechanisms in Plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 2018, 88, 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzarides, T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell 2007, 128, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransz, P.F.; de Jong, J.H. Chromatin dynamics in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilberman, D.; Gehring, M.; Tran, R.K.; Ballinger, T.; Henikoff, S. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methylation uncovers an interdependence between methylation and transcription. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Kimatu, J.N.; Xu, K.; Liu, B. DNA cytosine methylation in plant development. J. Genet. Genom. 2010, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Dong, A.; Shen, W.H. Histone variants and chromatin assembly in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1819, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentry, M.; Hennig, L. Remodelling chromatin to shape development of plants. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 321, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashapkin, V.V.; Kutueva, L.I.; Aleksandrushkina, N.I.; Vanyushin, B.F. Epigenetic Mechanisms of Plant Adaptation to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.A.; Jacobsen, S.E. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010, 11, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruenbaum, Y.; Naveh-Many, T.; Cedar, H.; Razin, A. Sequence specificity of methylation in higher plant DNA. Nature 1981, 292, 860–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, H.; Greenberg, M.V.C.; Feng, S.; Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Jacobsen, S.E. Comprehensive analysis of silencing mutants reveals complex regulation of the Arabidopsis methylome. Cell 2013, 152, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroud, H.; Do, T.; Du, J.; Zhong, X.; Feng, S.; Johnson, L.; Patel, D.J.; Jacobsen, S.E. Non-CG methylation patterns shape the epigenetic landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Jacobsen, S.E. Locus-specific control of asymmetric and CpNpG methylation by the DRM and CMT3 methyltransferase genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99 (Suppl. 4), 16491–16498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jacobsen, S.E. Genetic analyses of DNA methyltransferases in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2006, 71, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lang, Z.; Zhu, J.K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wambui Mbichi, R.; Wang, Q.F.; Wan, T. RNA directed DNA methylation and seed plant genome evolution. Plant Cell Rep. 2020, 39, 983–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Mosher, R.A. RNA-directed DNA methylation: An epigenetic pathway of increasing complexity. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.K. RNA-directed DNA methylation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikaard, C.S.; Haag, J.R.; Pontes, O.M.F.; Blevins, T.; Cocklin, R. A transcription fork model for Pol IV and Pol V-dependent RNA-directed DNA methylation. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2012, 77, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Gil, D.; Slotkin, R.K. Non-canonical RNA-directed DNA methylation. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penterman, J.; Uzawa, R.; Fischer, R.L. Genetic Interactions between DNA Demethylation and Methylation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, J.K. Active DNA demethylation in plants and animals. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2012, 77, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Galisteo, A.P.; Morales-Ruiz, T.; Ariza, R.R.; Roldán-Arjona, T. Arabidopsis DEMETER-LIKE proteins DML2 and DML3 are required for appropriate distribution of DNA methylation marks. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Macias, M.I.; Qian, W.; Miki, D.; Pontes, O.; Liu, Y.; Tang, K.; Liu, R.; Morales-Ruiz, T.; Ariza, R.R.; Roldán-Arjona, T.; et al. A DNA 3′ phosphatase functions in active DNA demethylation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Jang, H.; Shin, H.; Choi, W.L.; Mok, Y.G.; Huh, J.H. AP endonucleases process 5-methylcytosine excision intermediates during active DNA demethylation in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 11408–11418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cordoba-Canero, D.; Qian, W.; Zhu, X.; Tang, K.; Zhang, H.; Ariza, R.R.; Roldan-Arjona, T.; Zhu, J.K. An AP endonuclease functions in active DNA demethylation and gene imprinting in Arabidopsis [corrected]. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1004905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ruiz, T.; Ortega-Galisteo, A.P.; Ponferrada-Marín, M.I.; Martínez-Macías, M.I.; Ariza, R.R.; Roldán-Arjona, T. DEMETER and REPRESSOR OF SILENCING 1 encode 5-methylcytosine DNA glycosylases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 6853–6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penterman, J.; Zilberman, D.; Huh, J.H.; Ballinger, T.; Henikoff, S.; Fischer, R.L. DNA demethylation in the Arabidopsis genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6752–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Kapoor, A.; Sridhar, V.V.; Agius, F.; Zhu, J.K. The DNA glycosylase/lyase ROS1 functions in pruning DNA methylation patterns in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, Y. TET-mediated active DNA demethylation: Mechanism, function and beyond. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 517–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, A.M.; Dunwell, J.M. Evidence for novel epigenetic marks within plants. AIMS Genet. 2019, 6, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, L.; Jordan, W.T.; Shi, X.; Hu, L.; He, C.; Schmitz, R.J. TET-mediated epimutagenesis of the Arabidopsis thaliana methylome. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Z.; Shen, L.; Cui, X.; Bao, S.; Geng, Y.; Yu, G.; Liang, F.; Xie, S.; Lu, T.; Gu, X.; et al. DNA N(6)-Adenine Methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Dev. Cell 2018, 45, 406–416.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuno, S.; Gaut, B.S. Body-methylated genes in Arabidopsis thaliana are functionally important and evolve slowly. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domcke, S.; Bardet, A.F.; Ginno, P.A.; Hartl, D.; Schübeler, L.B.; Schübeler, D. Competition between DNA methylation and transcription factors determines binding of NRF1. Nature 2015, 528, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, G.; Qian, J. Transcription factors as readers and effectors of DNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuno, S.; Gaut, B. Gene body methylation is conserved between plant orthologs and is of evolutionary consequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, M.; Henikoff, S. DNA methylation dynamics in plant genomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1769, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, R.K.; Henikoff, J.G.; Zilberman, D.; Ditt, R.F.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Henikoff, S. DNA methylation profiling identifies CG methylation clusters in Arabidopsis genes. Curr. Biol. 2005, 15, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brautigam, K.; Cronk, Q. DNA Methylation and the Evolution of Developmental Complexity in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.; Melake-Berhan, A.; O’Brien, K.; Buckley, S.; Quan, H.; Chen, D.; Lewis, M.; Banks, J.A.; Rabinowicz, P.D. The highest-copy repeats are methylated in the small genome of the early divergent vascular plant Selaginella moellendorffii. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Cokus, S.J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, P.Y.; Bostick, M.; Goll, M.G.; Hetzel, J.; Jain, J.; Strauss, S.H.; Halpern, M.E.; et al. Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8689–8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemach, A.; McDaniel, I.E.; Silva, P.; Zilberman, D. Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of eukaryotic DNA methylation. Science 2010, 328, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederhuth, C.E.; Bewick, A.J.; Ji, L.; Alabady, M.S.; Kim, K.D.; Li, Q.; Rohr, N.A.; Rambani, A.; Burke, J.M.; Udall, J.A.; et al. Widespread natural variation of DNA methylation within angiosperms. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.Y.; Xiao, R.J.; Gu, L.; Guo, Y.G.; Wen, R.; Wan, L.J. Interfacial Mechanism in Lithium-Sulfur Batteries: How Salts Mediate the Structure Evolution and Dynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8147–8155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mohapatra, T. Dynamics of DNA Methylation and Its Functions in Plant Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 596236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, J.D.; Gaut, B.S. Epigenetic silencing of transposable elements: A trade-off between reduced transposition and deleterious effects on neighboring gene expression. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Sarazin, A.; Bowler, C.; Colot, V.; Quesneville, H. Genome-wide evidence for local DNA methylation spreading from small RNA-targeted sequences in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 6919–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Gent, J.I.; Zynda, G.; Song, J.; Makarevitch, I.; Hirsch, C.D.; Hirsch, C.N.; Dawe, R.K.; Madzima, T.F.; McGinnis, K.M.; et al. RNA-directed DNA methylation enforces boundaries between heterochromatin and euchromatin in the maize genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 14728–14733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cokus, S.J.; Feng, S.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Merriman, B.; Haudenschild, C.D.; Pradhan, S.; Nelson, S.F.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 2008, 452, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudier, F.; Ahmed, I.; Bérard, C.; Sarazin, A.; Mary-Huard, T.; Cortijo, S.; Bouyer, D.; Caillieux, E.; Duvernois-Berthet, E.; Al-Shikhley, L.; et al. Integrative epigenomic mapping defines four main chromatin states in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1928–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernatavichute, Y.V.; Zhang, X.; Cokus, S.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E. Genome-wide association of histone H3 lysine nine methylation with CHG DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grob, S.; Schmid, M.W.; Grossniklaus, U. Hi-C analysis in Arabidopsis identifies the KNOT, a structure with similarities to the flamenco locus of Drosophila. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 678–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Cokus, S.J.; Schubert, V.; Zhai, J.; Pellegrini, M.; Jacobsen, S.E. Genome-wide Hi-C analyses in wild-type and mutants reveal high-resolution chromatin interactions in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, M.J.; Rothi, M.H.; Böhmdorfer, G.; Kuciński, J.; Wierzbicki, A.T. Long-range control of gene expression via RNA-directed DNA methylation. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Jin, B. Genome-Wide Identification of Circular RNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Cui, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Fan, D.; Gong, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, D.; et al. Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. RNA 2015, 21, 2076–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, P.; Fan, Y.; Lu, Q.; Li, Q.; Yan, J.; Muehlbauer, G.J.; Schnable, P.S.; Dai, M.; Li, L. Circular RNAs mediated by transposons are associated with transcriptomic and phenotypic variation in maize. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1292–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeck, W.R.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Wang, K.; Slevin, M.K.; Burd, C.E.; Liu, J.; Marzluff, W.F.; Sharpless, N.E. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 2013, 19, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Tsukahara, T. A view of pre-mRNA splicing from RNase R resistant RNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 9331–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.L.; Yang, L. Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xi, F.; Wang, H.; Kohnen, M.V.; Gao, P.; Wei, W.; Chen, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Whole-genome characterization of chronological age-associated changes in methylome and circular RNAs in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) from vegetative to floral growth. Plant J. 2021, 106, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Chu, S.; Jiao, Y. Present Scenario of Circular RNAs (circRNAs) in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Wu, L. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauer, J.; Luo, X.; Blanjoie, A.; Jiao, X.; Grozhik, A.V.; Patil, D.P.; Linder, B.; Pickering, B.F.; Vasseur, J.J.; Chen, Q.; et al. Reversible methylation of m(6)Am in the 5′ cap controls mRNA stability. Nature 2017, 541, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.S.; Wang, X.; Beadell, A.V.; Lu, Z.; Shi, H.; Kuuspalu, A.; Ho, R.K.; He, C. m6A-dependent maternal mRNA clearance facilitates zebrafish maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nat. Plants 2017, 542, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.H.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Tang, Q.; Yu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Duan, H.C.; Jia, G. The m(6)A Reader ECT2 Controls Trichome Morphology by Affecting mRNA Stability in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 968–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.J.; Ping, X.L.; Chen, Y.S.; Wang, W.J.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussmann, I.U.; Bodi, Z.; Sanchez-Moran, E.; Mongan, N.P.; Archer, N.; Fray, R.G.; Soller, M. m(6)A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature 2016, 540, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, W.; Adhikari, S.; Dahal, U.; Chen, Y.S.; Hao, Y.J.; Sun, B.F.; Sun, H.Y.; Li, A.; Ping, X.L.; Lai, W.-Y.; et al. Nuclear m(6)A Reader YTHDC1 Regulates mRNA Splicing. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 507–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fustin, J.M.; Doi, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Hida, H.; Nishimura, S.; Yoshida, M.; Isagawa, T.; Morioka, M.S.; Kakeya, H.; Manabe, I.; et al. RNA-methylation-dependent RNA processing controls the speed of the circadian clock. Cell 2013, 155, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.L.; Song, S.H.; et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.D.; Patil, D.P.; Zhou, J.; Zinoviev, A.; Skabkin, M.A.; Elemento, O.; Pestova, T.V.; Qian, S.B.; Jaffrey, S.R. 5′ UTR m(6)A Promotes Cap-Independent Translation. Cell 2015, 163, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Ma, H.; Weng, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, H.; He, C. N6-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Leong, K.W.; Demirci, H.; Chen, J.; Petrov, A.; Prabhakar, A.; O’Leary, S.E.; Dominissini, D.; Rechavi, G.; Soltis, S.M. N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Riaz, A.; Chachar, S.; Ding, Y.; Hai Du, H.; Gu, X. Epigenetic Modifications of mRNA and DNA in Plants. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Li, H.; Bodi, Z.; Button, J.; Vespa, L.; Herzog, M.; Fraya, R.G. MTA is an Arabidopsis messenger RNA adenosine methylase and interacts with a homolog of a sex-specific splicing factor. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.; Liang, Z.; Gu, X.; Chen, Y.; Teo, Z.W.N.; Hou, X.; Cai, W.M.; Dedon, P.C.; Liu, L.; Yu, H. N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates shoot stem cell fate in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Liang, Z.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Bao, S.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Leo, V.; Vardy, L.A.; Lu, T.; et al. 5-Methylcytosine RNA Methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 1387–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Rao, C.M. Epigenetic tools (The Writers, The Readers and The Erasers) and their implications in cancer therapy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 837, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Manduzio, S.; Kang, H. Epitranscriptomic RNA Methylation in Plant Development and Abiotic Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruzicka, K.; Zhang, M.; Campilho, A.; Bodi, Z.; Kashif, M.; Saleh, M.; Eeckhout, D.; El-Showk, S.; Li, H.; Zhong, S.; et al. Identification of factors required for m(6) A mRNA methylation in Arabidopsis reveals a role for the conserved E3 ubiquitin ligase HAKAI. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodi, Z.; Zhong, S.; Mehra, S.; Song, J.; Graham, N.; Li, H.; May, S.; Fray, R.G. Adenosine Methylation in Arabidopsis mRNA is Associated with the 3’ End and Reduced Levels Cause Developmental Defects. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R.; Burgess, A.; Parker, B.; Li, J.; Pulsford, K.; Sibbritt, T.; Preiss, T.; Searle, I.R. Transcriptome-Wide Mapping of RNA 5-Methylcytosine in Arabidopsis mRNAs and Noncoding RNAs. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielecki, D.; Zugaj, D.Ł.; Muszewska, A.; Piwowarski, J.; Chojnacka, A.; Mielecki, M.; Nieminuszczy, J.; Grynberg, M.; Grzesiuk, E. Novel AlkB dioxygenases —Alternative models for in silico and in vivo studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30588. [Google Scholar]

- Arribas-Hernandez, L.; Bressendorff, S.; Hansen, M.H.; Poulsen, C.; Erdmann, S.; Brodersen, P. An m(6)A-YTH Module Controls Developmental Timing and Morphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 952–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamura, Y.; Nagahara, S.; Higashiyama, T. Double fertilization on the move. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rudall, P.J. How many nuclei make an embryo sac in flowering plants? BioEssays 2006, 28, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haig, D.; Westoby, M. Genomic imprinting in endosperm: Its effect on seed development in crosses between species, and between different ploidies of the same species, and its implications for the evolution of apomixis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond 1991, 333, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R.J.; Spielman, M.; Bailey, J.; Dickinson, H.G. Parent-of-origin effects on seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 1998, 125, 3329–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, Y. Plant imprinted genes identified by genome-wide approaches and their regulatory mechanisms. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kinoshita, T.; Yadegari, R.; Harada, J.J.; Goldberg, R.B.; Fischer, R.L. Imprinting of the MEDEA polycomb gene in the Arabidopsis endosperm. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, M.; Bubb, K.L.; Henikoff, S. Extensive demethylation of repetitive elements during seed development underlies gene imprinting. Science 2009, 324, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.F.; Ibarra, C.A.; Silva, P.; Zemach, A.; Eshed-Williams, L.; Fischer, R.L.; Zilberman, D. Genome-wide demethylation of Arabidopsis endosperm. Science 2009, 324, 1451–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klosinska, M.; Picard, C.L.; Gehring, M. Conserved imprinting associated with unique epigenetic signatures in the Arabidopsis genus. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinoshita, T.; Miura, A.; Choi, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Cao, X.; Jacobsen, S.E.; Fischer, R.L. KakutOne-way control of FWA imprinting in Arabidopsis endosperm by DNA methylation. Science 2004, 303, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Bilodeau, P.; Dennis, E.S.; Peacock, W.J.; Chaudhury, A. Expression and parent-of-origin effects for FIS2, MEA, and FIE in the endosperm and embryo of developing Arabidopsis seeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10637–10642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jullien, P.E.; Kinoshita, T.; Ohad, N.; Berger, F. Maintenance of DNA methylation during the Arabidopsis life cycle is essential for parental imprinting. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyosue, T.; Ohad, N.; Yadegari, R.; Hannon, M.; Dinneny, J.; Wells, D.; Katz, A.; Margossian, L.; Harada, J.J.; Goldberg, R.B.; et al. Control of fertilization-independent endosperm development by the MEDEA polycomb gene in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4186–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, C.; Hennig, L.; Spillane, C.; Pien, S.; Gruissem, W.; Grossniklaus, U. The Polycomb-group protein MEDEA regulates seed development by controlling expression of the MADS-box gene PHERES1. Genes Dev. 2003, 17, 1540–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemach, A.; Kim, M.Y.; Silva, P.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Dotson, B.; Brooks, M.D.; Zilberman, D. Local DNA hypomethylation activates genes in rice endosperm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18729–18734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, W.; Ren, W.; Chai, Z.; Guo, W.; Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Lang, Z.; Fan, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Epigenetic Regulation of Gene Transcription in Maize Seeds. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slotkin, R.K.; Vaughn, M.; Borges, F.; Tanurdzić, M.; Becker, J.D.; Feijó, J.A.; Martienssen, R.A. Epigenetic reprogramming and small RNA silencing of transposable elements in pollen. Cell 2009, 136, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoft, V.K.; Chumak, N.; Choi, Y.; Hannon, M.; Garcia-Aguilar, M.; Machlicova, A.; Slusarz, L.; Mosiolek, M.; Park, J.S.; Park, G.T.; et al. Function of the DEMETER DNA glycosylase in the Arabidopsis thaliana male gametophyte. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8042–8047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calarco, J.P.; Borges, F.; Donoghue, M.T.A.; Van Ex, F.; Jullien, P.E.; Lopes, L.; Gardner, R.; Berger, F.; Feijó, J.A.; Becker, J.D.; et al. Reprogramming of DNA methylation in pollen guides epigenetic inheritance via small RNA. Cell 2012, 151, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, C.A.; Feng, X.; Schoft, V.K.; Hsieh, T.F.; Uzawa, R.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Zemach, A.; Chumak, N.; Machlicova, A.; Nishimura, T.; et al. Active DNA demethylation in plant companion cells reinforces transposon methylation in gametes. Science 2012, 337, 1360–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordyum, E.L.; Mosyakin, S.L. Endosperm of Angiosperms and Genomic Imprinting. Life 2020, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hieber, A.D.; Mudalige-Jayawickrama, R.G.; Kuehnle, A.R. Color genes in the orchid Oncidium Gower Ramsey: Identification, expression, and potential genetic instability in an interspecific cross. Planta 2006, 223, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, C.Y.; Pan, H.A.; Chuang, Y.N.; Yeh, K.W. Differential expression of carotenoid-related genes determines diversified carotenoid coloration in floral tissues of Oncidium cultivars. Planta 2010, 232, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Chuang, Y.N.; Chiou, C.Y.; Chin, D.C.; Shen, F.Q.; Yeh, K.W. Methylation effect on chalcone synthase gene expression determines anthocyanin pigmentation in floral tissues of two Oncidium orchid cultivars. Planta 2012, 236, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.L.; Yin, J.; Zhao, Y.H.; Sun, X.W.; Meng, J.X.; Zhou, J.; Shen, T.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, F. How the Color Fades from Malus halliana Flowers: Transcriptome Sequencing and DNA Methylation Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 576054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Ma, K.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q. Integration of Transcriptome and Methylome Analyses Provides Insight Into the Pathway of Floral Scent Biosynthesis in Prunus mume. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 779557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Huo, T.; Ding, A.; Hao, R.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Bao, F.; Zhang, Q. Genome-wide identification, characterization, expression and enzyme activity analysis of coniferyl alcohol acetyltransferase genes involved in eugenol biosynthesis in Prunus mume. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, F.; Ding, A.; Zhang, T.; Luo, L.; Wang, J.; Cheng, T.; Zhang, Q. Expansion of PmBEAT genes in the Prunus mume genome induces characteristic floral scent production. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chang, X.; Yan, M.; Zhao, H.; Qin, Y.; Wang, H. Integrated analysis of DNA methylome and transcriptome reveals epigenetic regulation of CAM photosynthesis in pineapple. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, G.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A.; Li, M.; Zhao, C.; He, C.; Si, C.; Zhang, M.; Duan, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of DNA methyltransferase and demethylase gene families in Dendrobium officinale reveal their potential functions in polysaccharide accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, C.; Chen, L.; Fu, H.; Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Lai, Z.; Guo, Y. Genome-wide investigation and transcriptional analysis of cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase and DNA demethylase gene families in tea plant (Camellia sinensis) under abiotic stress and withering processing. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubin, M.J.; Zhang, P.; Meng, D.; Remigereau, M.S.; Osborne, E.J.; Casale, P.F.; Drewe, P.; Kahles, A.; Jean, G.; Vilhjálmsson, B.; et al. DNA methylation in Arabidopsis has a genetic basis and shows evidence of local adaptation. eLife 2015, 4, e05255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, N.; Ito, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Koizumi, N.; Sano, H. Periodic DNA methylation in maize nucleosomes and demethylation by environmental stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 37741–37746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.P.; Ferreira, L.J.; Oliveira, M.M. Concerted Flexibility of Chromatin Structure, Methylome, and Histone Modifications along with Plant Stress Responses. Biology 2017, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coen, E.S.; Carpenter, R.; Martin, C. Transposable elements generate novel spatial patterns of gene expression in Antirrhinum majus. Cell 1986, 47, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida, S.N.; Kitamura, K.; Mikami, T.; Kishima, Y. Temperature shift coordinately changes the activity and the methylation state of transposon Tam3 in Antirrhinum majus. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconi, G.; Pace, R.; Traini, A.; Raggi, L.; Lutts, S.; Chiusano, M.; Guiducci, M.; Falcinelli, M.; Benincasa, P.; Albertini, E. Use of MSAP markers to analyse the effects of salt stress on DNA methylation in rapeseed (Brassica napus var. oleifera). PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e75597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karan, R.; DeLeon, T.; Biradar, H.; Subudhi, P.K. Salt stress induced variation in DNA methylation pattern and its influence on gene expression in contrasting rice genotypes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.J.; Azevedo, V.; Maroco, J.; Oliveira, M.M.; Santos, A.P. Salt Tolerant and Sensitive Rice Varieties Display Differential Methylome Flexibility under Salt Stress. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, R.M.; Ricardi, M.M.; Iusem, N.D. Epigenetic marks in an adaptive water stress-responsive gene in tomato roots under normal and drought conditions. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, K.Y.; Khodaeiaminjan, M.; Yahya, G.; El-Tantawy, A.A.; Abdel El-Moneim, D.; El-Esawi, M.A.; Abd-Elaziz, M.A.A.; Nassrallah, A.A. Modulation of cell cycle progression and chromatin dynamic as tolerance mechanisms to salinity and drought stress in maize. Physiol. Plant 2021, 172, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanova, V.; Popov, M.; Pavlíková, D.; Kotrba, P.; Hnilička, F.; Česká, J.; Pavlík, M. Effect of arsenic stress on 5-methylcytosine, photosynthetic parameters and nutrient content in arsenic hyperaccumulator Pteris cretica (L.) var. Albo-lineata. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, M.; Torelli, A.; Marieschi, M.; Cozza, R. Role of DNA methylation in the chromium tolerance of Scenedesmus acutus (Chlorophyceae) and its impact on the sulfate pathway regulation. Plant Sci. 2020, 301, 110680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, O.; Burke, P.; Arkhipov, A.; Kuchma, N.; James, S.J.; Kovalchuk, I.; Pogribny, I. Genome hypermethylation in Pinus silvestris of Chernobyl—A mechanism for radiation adaptation? Mutat. Res. 2003, 529, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambani, A.; Rice, J.H.; Liu, J.; Lane, T.; Ranjan, P.; Mazarei, M.; Pantalone, V.; Stewart, C.N., Jr.; Staton, M.; Hewezi, T. The Methylome of Soybean Roots during the Compatible Interaction with the Soybean Cyst Nematode. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 1364–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewezi, T.; Lane, T.; Piya, S.; Rambani, A.; Rice, J.H.; Staton, M. Cyst Nematode Parasitism Induces Dynamic Changes in the Root Epigenome. Plant Physiol. 2017, 174, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Huang, H.; Lin, X.; Zhu, C.; Kosami, K.I.; Huang, C.; Zhang, H.; Duan, C.G.; Zhu, J.K.; Miki, D. Roles of DEMETER in regulating DNA methylation in vegetative tissues and pathogen resistance. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 691–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipple, C. Plant science. Defining the plant germ line—Nature or nurture? Science 2012, 337, 301–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronk, Q.C. Plant evolution and development in a post-genomic context. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001, 2, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, J.; Grossniklaus, U. Selected aspects of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance and resetting in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, A.; Prasad, S.; Mitra, J.; Siddiqui, N.; Sahoo, L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Koyama, H. How do plants remember drought? Planta 2022, 256, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.M. Epigenetic responses to environmental change and their evolutionary implications. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3403–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, E.J. Inherited epigenetic variation—Revisiting soft inheritance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paun, O.; Bateman, R.M.; Fay, M.F.; Hedrén, M.; Civeyrel, L.; Chase, M.W. Stable epigenetic effects impact adaptation in allopolyploid orchids (Dactylorhiza: Orchidaceae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Shi, T. Distinct methylome patterns contribute to ecotypic differentiation in the growth of the storage organ of a flowering plant (sacred lotus). Mol. Ecol. 2021, 30, 2831–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucibelli, F.; Valoroso, M.C.; Aceto, S. Radial or Bilateral? The Molecular Basis of Floral Symmetry. Genes 2020, 11, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citerne, H.J.; Jabbour, F.; Nadot, S.; Dameval, C. The evolution of floral symmetry. Adv. Bot. Res. 2010, 54, 85–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hsin, K.T.; Wang, C.N. Expression shifts of floral symmetry genes correlate to flower actinomorphy in East Asia endemic Conandron ramondioides (Gesneriaceae). Bot. Stud. 2018, 59, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, W.; Gallagher, P.; Nolan, K.M.; Wright, H.; Cardeñosa-Rubio, M.C.; Bragalini, C.; Lee, C.S.; Fitzpatrick, D.A.; Corcoran, K.; Wolff, K.; et al. Different outcomes for the MYB floral symmetry genes DIVARICATA and RADIALIS during the evolution of derived actinomorphy in Plantago. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubas, P.; Vincent, C.; Coen, E. An epigenetic mutation responsible for natural variation in floral symmetry. Nature 1999, 401, 157–161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.; Pérez, R.; Bazaga, P.; Herrera, C.M. Global DNA cytosine methylation as an evolving trait: Phylogenetic signal and correlated evolution with genome size in angiosperms. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzke, M.A.; Kanno, T.; Matzke, A.J. RNA-Directed DNA Methylation: The Evolution of a Complex Epigenetic Pathway in Flowering Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2015, 66, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Patel, N.; Keung, A.J.; Khalil, A.S. Engineering Epigenetic Regulation Using Synthetic Read-Write Modules. Cell 2019, 176, 227–238.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.R.; Sherif, S.M. Application of Exogenous dsRNAs-induced RNAi in Agriculture: Challenges and Triumphs. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallego-Bartolome, J. DNA methylation in plants: Mechanisms and tools for targeted manipulation. New Phytol. 2020, 227, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Genes | Protein | Phenotype | Stress | Methylation State |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. officinale | DoC5-MTase | methylase | biosynthesis of WSPs | cold | methylated |

| D. officinale | DodMTase | demethylase | biosynthesis of WSPs | cold | demethylated |

| C. sinensis | C5-MTase | methylase | cold/drought | methylated | |

| C. sinensis | CsdMTase | demethylase | cold/drought | demethylated | |

| B. napus Exagone | LCR | cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | cutin synthesis | salt | methylated |

| B. napus Toccata | LCR | cytochrome P450 monooxygenase | cutin synthesis | salt | unaltered |

| B. napus Exagone | TPS4 | trehalose phosphatase/synthase 4 | biosynthetic pathway of trehalose | salt | demethylated |

| B. napus Toccata | TPS4 | trehalose phosphatase/synthase 4 | biosynthetic pathway of trehalose | salt | methylated |

| S. lycopersicum | Asr2 | putative transcription factor | response to water-stress | drought | demethylated |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lucibelli, F.; Valoroso, M.C.; Aceto, S. Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158299

Lucibelli F, Valoroso MC, Aceto S. Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(15):8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158299

Chicago/Turabian StyleLucibelli, Francesca, Maria Carmen Valoroso, and Serena Aceto. 2022. "Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 15: 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158299

APA StyleLucibelli, F., Valoroso, M. C., & Aceto, S. (2022). Plant DNA Methylation: An Epigenetic Mark in Development, Environmental Interactions, and Evolution. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(15), 8299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158299