Glucocorticoid Receptor: A Multifaceted Actor in Breast Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

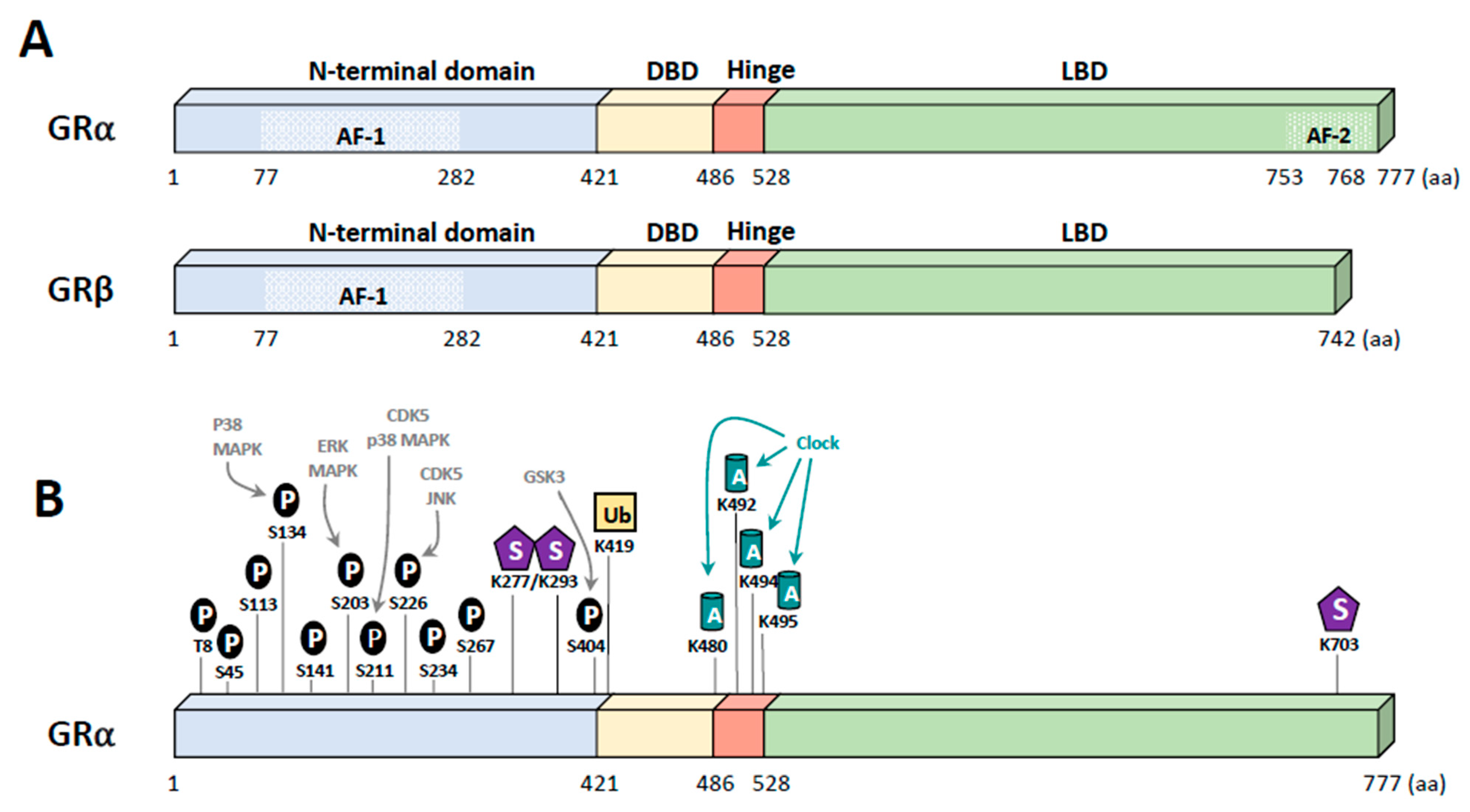

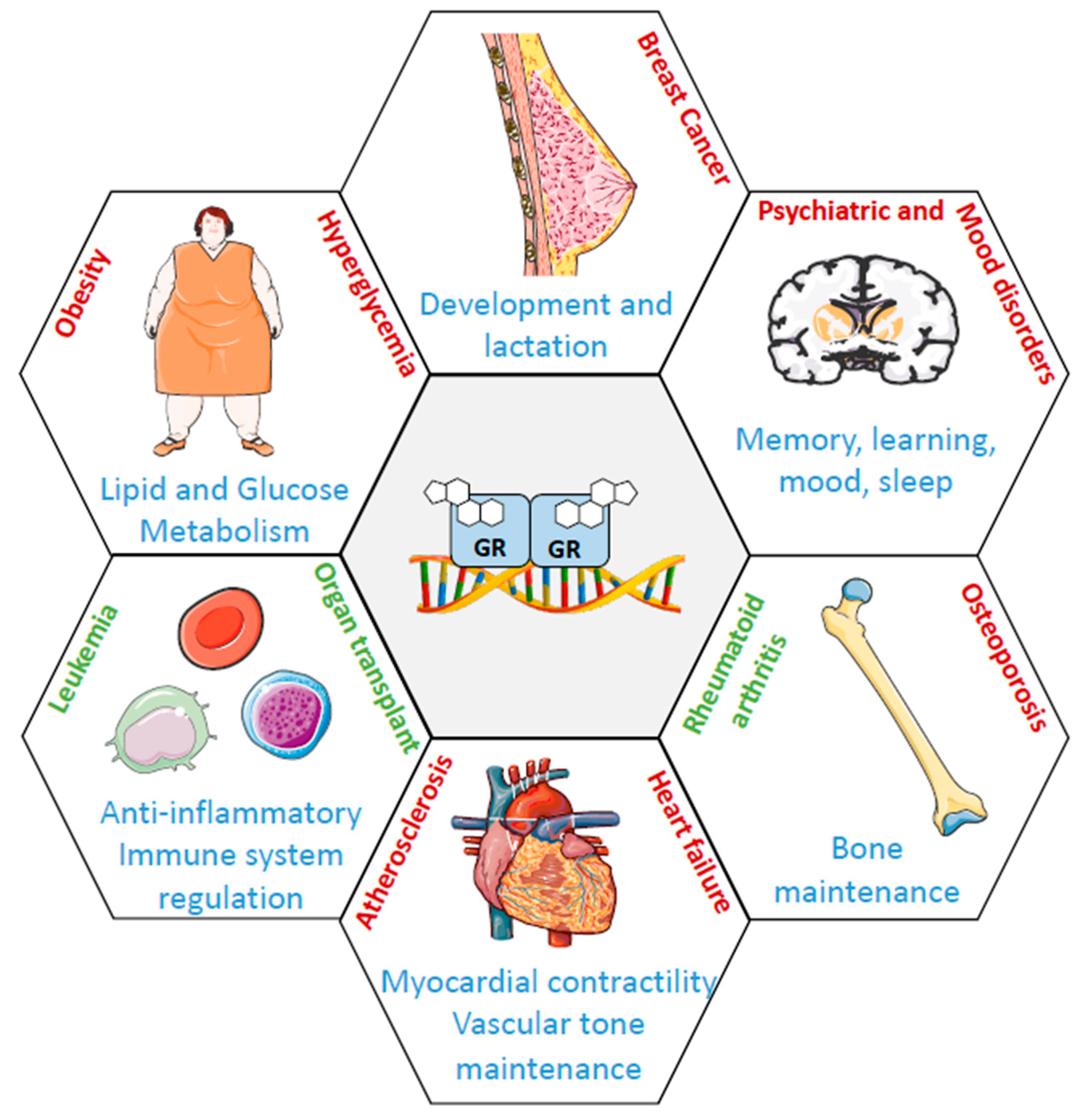

2. Glucocorticoid Receptor

3. GR Ligands

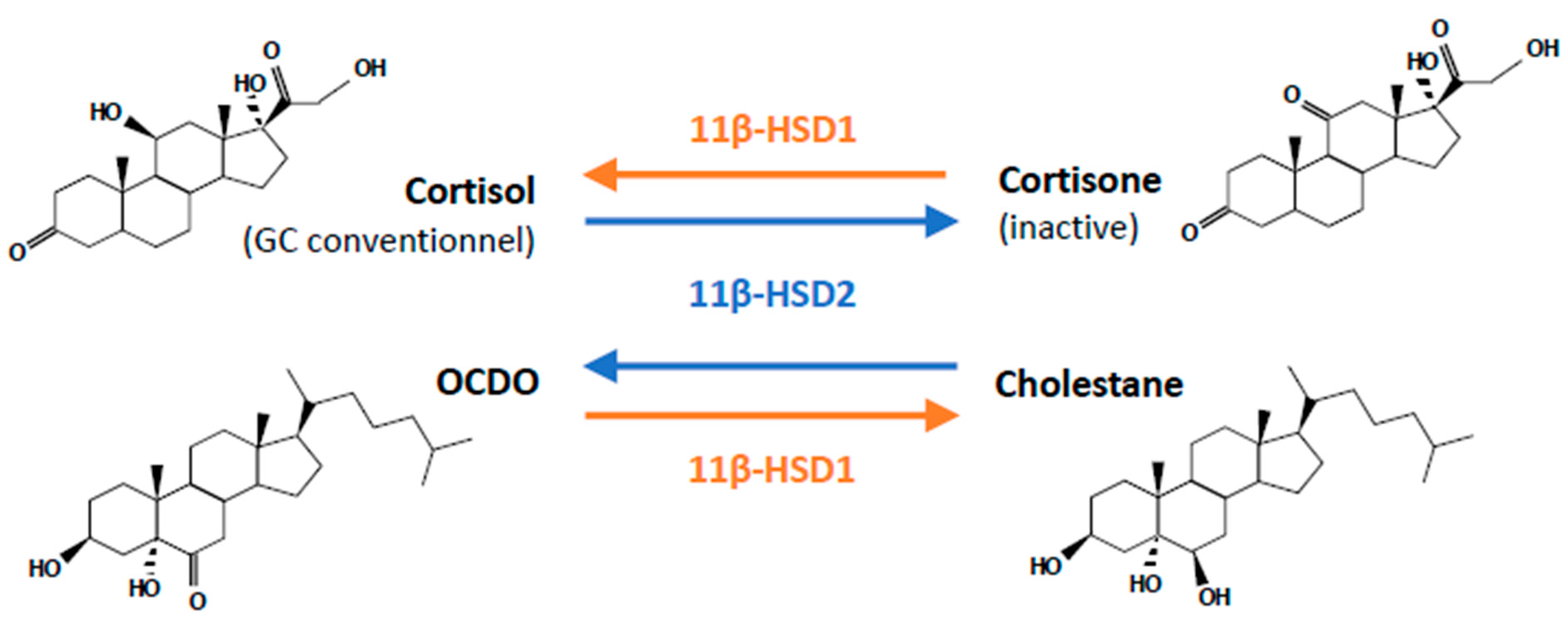

3.1. Glucocorticoids (GCs)

3.2. Synthetic GCs

3.3. OCDO

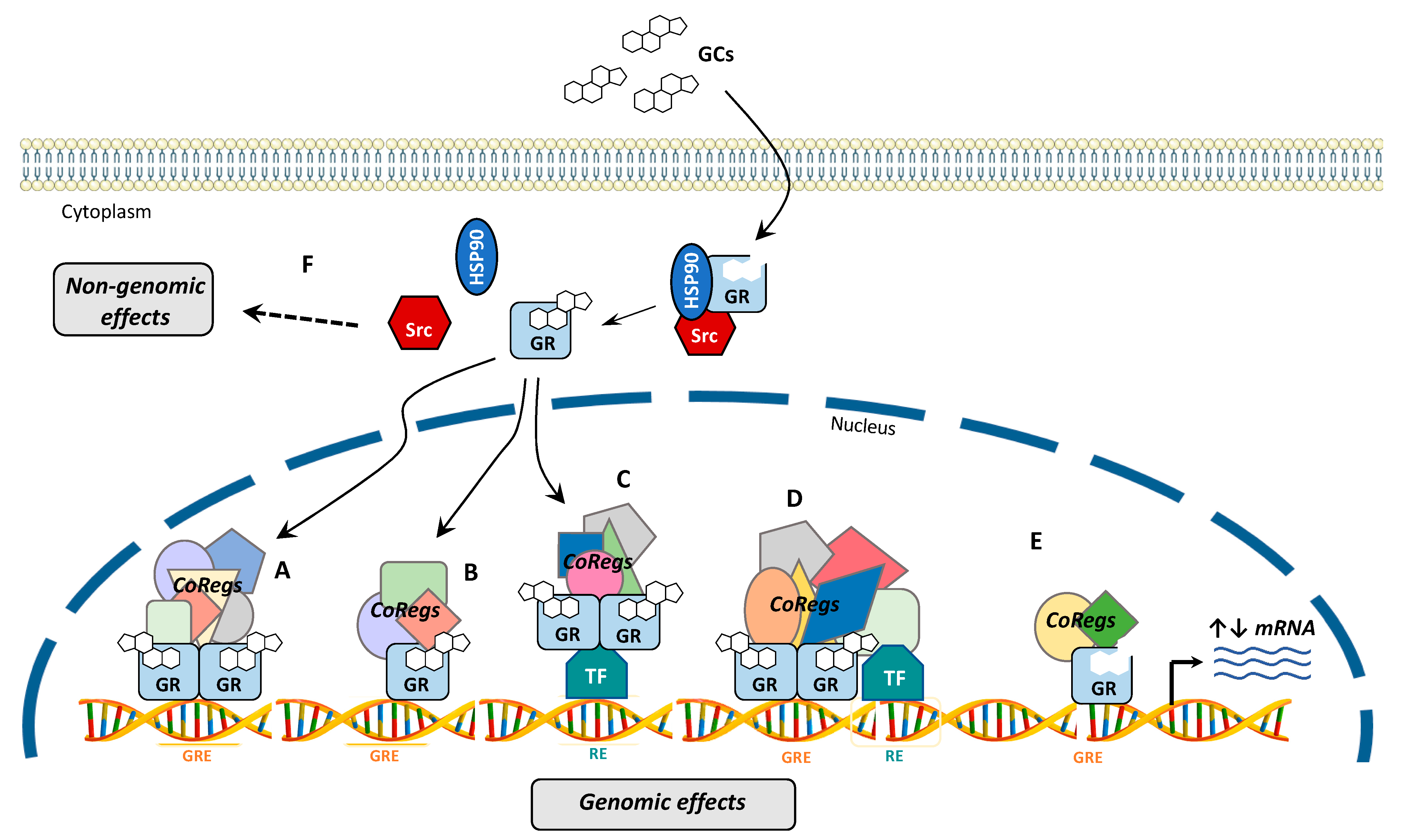

4. GR Signaling

5. Post-Translational Modifications of GR

5.1. Phosphorylation

5.2. Other Modifications

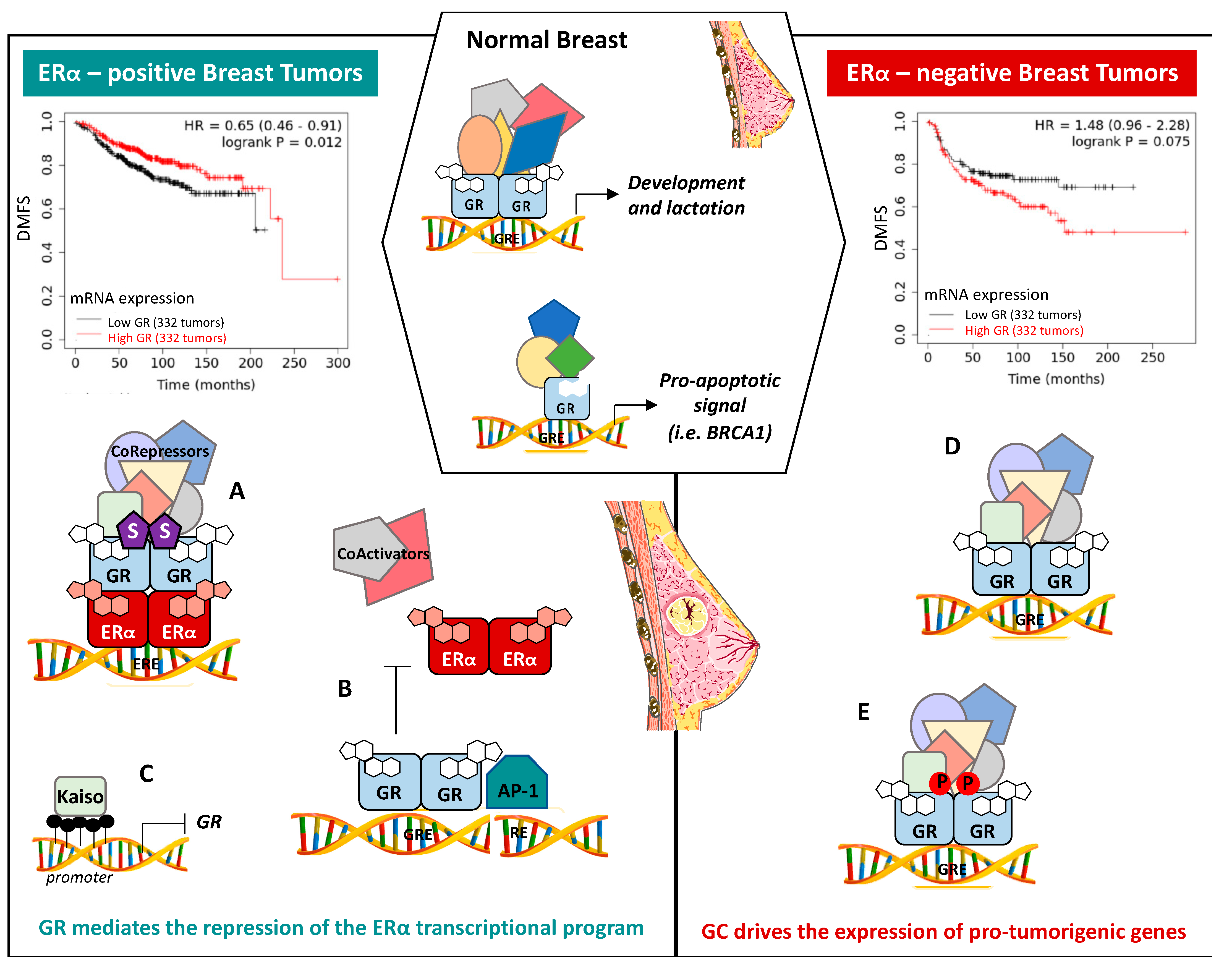

6. The Role of GR in Breast Tissue

7. The Role of GR in Breast Cancer Progression

7.1. ERα-Positive BCs

7.2. ERα-Negative BCs

8. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, I.; Patek, A. The relationship between prognostic and predictive factors in the management of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998, 52, 261–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, W.F.; Rosenberg, P.S.; Prat, A.; Perou, C.M.; Sherman, M.E. How many etiological subtypes of breast cancer: Two, three, four, or more? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, D.; Simpson, P.T.; Green, B.; Cummings, M.C.; Lakhani, S.R. Molecular classification of breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2014, 465, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, P. Triple-negative breast cancer: Epidemiological considerations and recommendations. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23 (Suppl. S6), vi7–vi12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temian, D.C.; Pop, L.A.; Irimie, A.I.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. The epigenetics of triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer: Current knowledge. J. Breast Cancer 2018, 21, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toft, D.J.; Cryns, V.L. Minireview: Basal-like breast cancer: From molecular profiles to targeted therapies. Mol. Endocrinol. 2011, 25, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waks, A.G.; Winer, E.P. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Review. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2019, 321, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamdade, V.S.; Sethi, N.; Mundhe, N.A.; Kumar, P.; Lahkar, M.; Sinha, N. Therapeutic targets of triple-negative breast cancer: A review. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 172, 4228–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Wang, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Meta-analysis of the effects of oral and intravenous dexamethasone premedication in the prevention of paclitaxel-induced allergic reactions. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 19236–19243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, D.C.; Pan, D.; Tonsing-Carter, E.Y.; Hernandez, K.M.; Pierce, C.F.; Styke, S.C.; Bowie, K.R.; Garcia, T.I.; Kocherginsky, M.; Conzen, S.D. GR and ER coactivation alters the expression of differentiation genes and associates with improved ER+ breast cancer outcome. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skor, M.N.; Wonder, E.L.; Kocherginsky, M.; Goyal, A.; Hall, B.A.; Cai, Y.; Conzen, S.D. Glucocorticoid receptor antagonism as a novel therapy for triple-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6163–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradović, M.M.S.; Hamelin, B.; Manevski, N.; Couto, J.P.; Sethi, A.; Coissieux, M.M.; Münst, S.; Okamoto, R.; Kohler, H.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Glucocorticoids promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 2019, 567, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govindan, M.V.; Devic, M.; Green, S.; Gronemeyer, H.; Chambon, P. Cloning of the human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985, 13, 8293–8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, S.; Souffriau, J.; Libert, C. A general introduction to glucocorticoid biology. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevyver, S.; Dejager, L.; Libert, C. Comprehensive overview of the structure and regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor. Endocr. Rev. 2014, 35, 671–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giguère, V.; Hollenberg, S.M.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Evans, R.M. Functional domains of the human glucocorticoid receptor. Cell 1986, 46, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenberg, S.M.; Weinberger, C.; Ong, E.S.; Cerelli, G.; Oro, A.; Lebo, R.; Thompson, E.B.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Evans, R.M. Primary structure and expression of a functional human glucocorticoid receptor cDNA. Nature 1985, 318, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nick, Z.L.U.; Cidlowski, J.A. The origin and functions of multiple human glucocorticoid receptor isoforms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2004, 1024, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakleyt, R.H.; Jewell, C.M.; Yudt, M.R.; Bofetiado, D.M.; Cidlowski, J.A. The dominant negative activity of the human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform. Specificity and mechanisms of action. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 27857–27866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, R.H.; Sar, M.; Cidlowski, J.A. The human glucocorticoid receptor β isoform: Expression, biochemical properties, and putative function. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9550–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kino, T.; Manoli, I.; Kelkar, S.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.A.; Chrousos, G.P. Glucocorticoid receptor (GR) β has intrinsic, GRα-independent transcriptional activity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, L.C.; Berry, A.A.; Morgan, D.J.; Poolman, T.M.; Bauer, K.; Kramer, F.; Spiller, D.G.; Richardson, R.V.; Chapman, K.E.; Farrow, S.N.; et al. Glucocorticoid receptor regulates accurate chromosome segregation and is associated with malignancy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5479–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Van Heerikhuize, J.; Aronica, E.; Kawata, M.; Seress, L.; Joels, M.; Swaab, D.F.; Lucassen, P.J. Glucocorticoid receptor protein expression in human hippocampus; stability with age. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS. Available online: https://atlasbar.sg/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Spiga, F.; Walker, J.J.; Terry, J.R.; Lightman, S.L. HPA axis-rhythms. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1273–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.L. Androgen synthesis in adrenarche. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2009, 10, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, G.L. Plasma steroid-binding proteins: Primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, R13–R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, N.; Stewart, P.M. 11Β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase and the Pre-Receptor Regulation of Corticosteroid Hormone Action. J. Endocrinol. 2005, 186, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckl, J.R. 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases: Changing glucocorticoid action. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2004, 4, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, N.C.; Galata, Z.; Kino, T.; Chrousos, G.P.; Charmandari, E. The human glucocorticoid receptor: Molecular basis of biologic function. Steroids 2010, 75, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F. A fresh look at glucocorticoids: How to use an old ally more effectively. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2012, 70, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Adcock, I.M.; Mumby, S. Glucocorticoids. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2016, 237, 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- Daley-Yates, P. Inhaled corticosteroids: Potency, dose equivalence and therapeutic index. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 80, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Q.; Morand, E.; Yang, Y.H. Development of novel treatment strategies for inflammatory diseases—Similarities and divergence between glucocorticoids and GILZ. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, P.J. Glucocorticosteroids: Current and future directions. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 163, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenstein, S.; Ghias, K.; Krett, N.L.; Rosen, S.T. Mechanisms of glucocorticoid-mediated apoptosis in hematological malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002, 8, 1681–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.T.; Wang, L.H. New dimension of glucocorticoids in cancer treatment. Steroids 2016, 111, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Malone, M.H.; He, H.; McColl, K.S.; Distelhorst, C.W. Microarray analysis uncovers the induction of the proapoptotic BH3-only protein Bim in multiple models of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 23861–23867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, B.D. Systematic review of the clinical effect of glucocorticoids on nonhematologic malignancy. BMC Cancer 2008, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirot, M.; Soules, R.; Mallinger, A.; Dalenc, F.; Silvente-Poirot, S. Chemistry, biochemistry, metabolic fate and mechanism of action of 6-oxo-cholestan-3β,5α-diol (OCDO), a tumor promoter and cholesterol metabolite. Biochimie 2018, 153, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, M.; De Medina, P.; Mallinger, A.; Dalenc, F.; Huc-Claustre, E.; Leignadier, J.; Serhan, N.; Soules, R.; Ségala, G.; Mougel, A.; et al. Identification of a tumor-promoter cholesterol metabolite in human breast cancers acting through the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9346–E9355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, M.; Silvente-poirot, S.; Poirot, M. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications One step synthesis of 6-oxo-cholestan-3 b, 5 a-diol. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 782–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirot, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S. The tumor-suppressor cholesterol metabolite, dendrogenin A, is a new class of LXR modulator activating lethal autophagy in cancers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 153, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grad, I.; Picard, D. The glucocorticoid responses are shaped by molecular chaperones. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007, 275, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, W.B.; Toft, D.O. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr. Rev. 1997, 18, 306–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikum, E.R.; Knuesel, M.T.; Ortlund, E.A.; Yamamoto, K.R. Glucocorticoid receptor control of transcription: Precision and plasticity via allostery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presman, D.M.; Hager, G.L. More than meets the dimer: What is the quaternary structure of the glucocorticoid receptor? Transcription 2017, 8, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.R. Steroid receptor regulated transcription of specific genes and gene networks. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1985, 19, 209–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, R.H.; Cidlowski, J.A. The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: New signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 132, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galon, J.; Franchimont, D.; Hiroi, N.; Frey, G.; Boettner, A.; Ehrhart-Bornstein, M.; O’shea, J.J.; Chrousos, G.P.; Bornstein, S.R. Gene profiling reveals unknown enhancing and suppressive actions of glucocorticoids on immune cells. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, H.D.; Antonova, L.; Mueller, C.R. The unliganded glucocorticoid receptor positively regulates the tumor suppressor gene BRCA1 through GABP beta. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, H.D.; Mueller, C.R. Expression microarray identifies the unliganded glucocorticoid receptor as a regulator of gene expression in mammary epithelial cells. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Xu, L.; Glass, C.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Coactivator and corepressor complexes in nuclear receptor function. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1999, 9, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.M.; Heitzer, M.D.; Grubisha, M.; DeFranco, D.B. Coactivators and nuclear receptor transactivation. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 104, 1580–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallcup, M.R.; Poulard, C. Gene-Specific Actions of Transcriptional Coregulators Facilitate Physiological Plasticity: Evidence for a Physiological Coregulator Code. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazin, M.J.; Kadonaga, J.T. SWI2/SNF2 and related proteins: ATP-driven motors that disrupt protein-DNA interactions? Cell 1997, 88, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, C.J.; Archer, T.K. Chromatin remodelling by the glucocorticoid receptor requires the BRG1 complex. Nature 1998, 393, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, K.B.; Yamamoto, K.R. The Glucocorticoid Receptor and the Coregulator Brm Selectively Modulate Each Other’s Occupancy and Activity in a Gene-Specific Manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2011, 31, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallberg, A.E.; Neely, K.E.; Hassan, A.H.; Gustafsson, J.-Å.; Workman, J.L.; Wright, A.P.H. Recruitment of the SWI-SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex as a Mechanism of Gene Activation by the Glucocorticoid Receptor τ1 Activation Domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muratcioglu, S.; Presman, D.M.; Pooley, J.R.; Grøntved, L.; Hager, G.L.; Nussinov, R.; Keskin, O.; Gursoy, A. Structural Modeling of GR Interactions with the SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complex and C/EBP. Biophys. J. 2015, 109, 1227–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothbart, S.B.; Strahl, B.D. Interpreting the language of histone and DNA modifications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2014, 1839, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenuwein, T.; Allis, C.D. Translating the histone code. Science 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Ma, M.; Hong, H.; Koh, S.S.; Huang, S.M.; Schurter, B.T.; Aswad, D.W.; Stallcup, M.R. Regulation of transcription by a protein methyltransferase. Science 1999, 284, 2174–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittencourt, D.; Wu, D.Y.; Jeong, K.W.; Gerke, D.S.; Herviou, L.; Ianculescu, I.; Chodankar, R.; Siegmund, K.D.; Stallcup, M.R. G9a functions as a molecular scaffold for assembly of transcriptional coactivators on a subset of Glucocorticoid Receptor target genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 19673–19678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallberg, A.E.; Neely, K.E.; Gustafsson, J.-Å.; Workman, J.L.; Wright, A.P.H.; Grant, P.A. Histone Acetyltransferase Complexes Can Mediate Transcriptional Activation by the Major Glucocorticoid Receptor Activation Domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 5952–5959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Stewart, M.D.; Wang, J. Nuclear Receptor Repression: Regulatory Mechanisms and Physiological Implications, 1st ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 87. [Google Scholar]

- Ronacher, K.; Hadley, K.; Avenant, C.; Stubsrud, E.; Simons, S.S., Jr.; Louw, A.; Hapgood, J.P. Ligand-selective transactivation and transrepression via the glucocorticoid receptor: Role of cofactor interaction. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2009, 299, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Hu, X.Q.; Zhang, L. Glucocorticoids and programming of the microenvironment in heart. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 242, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaherty, R.L.; Owen, M.; Fagan-Murphy, A.; Intabli, H.; Healy, D.; Patel, A.; Allen, M.C.; Patel, B.A.; Flint, M.S. Glucocorticoids induce production of reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species and DNA damage through an iNOS mediated pathway in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2017, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Frederick, J.; Garabedian, M.J. Deciphering the phosphorylation “code” of the glucocorticoid receptor in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 26573–26580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avenant, C.; Ronacher, K.; Stubsrud, E.; Louw, A.; Hapgood, J.P. Role of ligand-dependent GR phosphorylation and half-life in determination of ligand-specific transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 327, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L.; Webb, M.S.; Copik, A.J.; Wang, Y.; Johnson, B.H.; Kumar, R.; Thompson, E.B. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a key mediator in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoid cells: Correlation between p38 MAPK activation and site-specific phosphorylation of the human glucocorticoid receptor at serine 211. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Dang, T.; Blind, R.D.; Wang, Z.; Cavasotto, C.N.; Hittelman, A.B.; Rogatsky, I.; Logan, S.K.; Garabedian, M.J. Glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation differentially affects target gene expression. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 1754–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, M.; Adachi, M.; Yasui, H.; Takekawa, M.; Tanaka, H.; Imai, K. Nuclear export of glucocorticoid receptor is enhanced by c-Jun N-terminal kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 2382–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takabe, S.; Mochizuki, K.; Goda, T. De-phosphorylation of GR at Ser203 in nuclei associates with GR nuclear translocation and GLUT5 gene expression in Caco-2 cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 475, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliher-Beckley, A.J.; Williams, J.G.; Collins, J.B.; Cidlowski, J.A. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β-Mediated Serine Phosphorylation of the Human Glucocorticoid Receptor Redirects Gene Expression Profiles. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008, 28, 7309–7322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Piovan, E.; Yu, J.; Tosello, V.; Herranz, D.; Ambesi-Impiombato, A.; DaSilva, A.C.; Sanchez-Martin, M.; Perez-Garcia, A.; Rigo, I.; Castillo, M.; et al. Direct Reversal of Glucocorticoid Resistance by AKT Inhibition in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2013, 24, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Yamamura, S.; Essilfie-Quaye, S.; Cosio, B.; Ito, M.; Barnes, P.J.; Adcock, I.M. Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-kappaB suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, N.; Chrousos, G.P.; Kino, T. Circadian rhythm transcription factor CLOCK regulates the transcriptional activity of the glucocorticoid receptor by acetylating its hinge region lysine cluster: Potential physiological implications. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.D.; Cidlowski, J.A. Proteasome-mediated Glucocorticoid Receptor Degradation Restricts Transcriptional Signaling by Glucocorticoids. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 42714–42721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.D.; Cao, Y.; Chandramouleeswaran, S.; Cidlowski, J.A. Lysine 419 targets human glucocorticoid receptor for proteasomal degradation. Steroids 2010, 75, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, X.; DeFranco, D.B. Alternative effects of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway on glucocorticoid receptor down-regulation and transactivation are mediated by CHIP, an E3 ligase. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Poukka, H.; Palvimo, J.J.; Jänne, O.A. Small ubiquitin-related modifier-1 (SUMO-1) modification of the glucocorticoid receptor. Biochem. J. 2002, 367, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Drean, Y.; Mincheneau, N.; Le Goff, P.; Michel, D. Potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor transcriptional activity by sumoylation. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 3482–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmstrom, S.R.; Chupreta, S.; So, A.Y.L.; Iñiguez-Lluhí, J.A. SUMO-mediated inhibition of glucocorticoid receptor synergistic activity depends on stable assembly at the promoter but not on DAXX. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 2061–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulard, C.; Jacquemetton, J.; Pham, T.H.; Le Romancer, M. Using proximity ligation assay to detect protein arginine methylation. Methods 2020, 175, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, H.C.; Lu, Y.S.; Cheng, A.L.; Chang, W.C.; Jeng, Y.M.; Kuo, Y.H.; Huang, C.S.; Chang, K.J.; Yao, Y.T. Differential expression of glucocorticoid receptor in human breast tissues and related neoplasms. J. Pathol. 2006, 209, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buxant, F.; Engohan-Aloghe, C.; Noël, J.C. Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and glucocorticoid receptor expression in normal breast tissue, breast in situ carcinoma, and invasive breast cancer. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol. 2010, 18, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintermantel, T.M.; Bock, D.; Fleig, V.; Greiner, E.F.; Schütz, G. The epithelial glucocorticoid receptor is required for the normal timing of cell proliferation during mammary lobuloalveolar development but is dispensable for milk production. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005, 19, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, J.; McArdle, E.; Gilligan, E.; Thornton, L.; Furlong, F.; Martin, F. Organization of mammary epithelial cells into 3D acinar structures requires glucocorticoid and JNK signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, H.M.; Horsch, K.; Gröne, H.J.; Kolbus, A.; Beug, H.; Hynes, N.; Schütz, G. Mammary gland development and lactation are controlled by different glucocorticoid receptor activities. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2001, 145, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, H.M.; Kaestner, K.H.; Tuckermann, J.; Kretz, O.; Wessely, O.; Bock, R.; Gass, P.; Schmid, W.; Herrlich, P.; Angel, P.; et al. DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell 1998, 93, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M.N.; Dharmarajan, A.M.; Waddell, B.J. Glucocorticoids and progesterone prevent apoptosis in the lactating rat mammary gland. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertucci, P.Y.; Quaglino, A.; Pozzi, A.G.; Kordon, E.C.; Pecci, A. Glucocorticoid-induced impairment of mammary gland involution is associated with STAT5 and STAT3 signaling modulation. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 5730–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, D.; Kocherginsky, M.; Conzen, S.D. Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6360–6370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduljabbar, R.; Negm, O.H.; Lai, C.F.; Jerjees, D.A.; Al-Kaabi, M.; Hamed, M.R.; Tighe, P.J.; Buluwela, L.; Mukherjee, A.; Green, A.R.; et al. Clinical and biological significance of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) expression in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 150, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lan, X.; Wu, D.; Sunkel, B.; Ye, Z.; Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Clinton, S.K.; Jin, V.X.; Wang, Q. Ligand-dependent genomic function of glucocorticoid receptor in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrentino, G.; Ruggeri, N.; Zannini, A.; Ingallina, E.; Bertolio, R.; Marotta, C.; Neri, C.; Cappuzzello, E.; Forcato, M.; Rosato, A.; et al. Glucocorticoid receptor signalling activates YAP in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Ma, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Tan, Y.; Jin, C.; Ma, W.; Hu, Y.; Shen, J.; Ohgi, K.A.; et al. Glucocorticoid Receptor:MegaTrans Switching Mediates the Repression of an ERα-Regulated Transcriptional Program. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 321–331.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmakar, S.; Jin, Y.; Nagaich, A.K. Interaction of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) with estrogen receptor (ER) α and activator protein 1 (AP1) in dexamethasone-mediated interference of ERα activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 24020–24034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippman, M.; Bolan, G.; Huff, K. The Effects of Glucocorticoids and Progesterone on Hormoneresponsive Human Breast Cancer in Long-Term Tissue Culture. Cancer Res. 1976, 36, 4602–4609. [Google Scholar]

- Györffy, B.; Lanczky, A.; Eklund, A.C.; Denkert, C.; Budczies, J.; Li, Q.; Szallasi, Z. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 123, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goya, L.; Maiyar, A.C.; Ge, Y.; Firestone, G.L. Glucocorticoids induce a G1/G0 cell cycle arrest of Con8 rat mammary tumor cells that is synchronously reversed by steroid withdrawal or addition of transforming growth factor-α. Mol. Endocrinol. 1993, 7, 1121–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tonsing-Carter, E.; Hernandez, K.M.; Kim, C.R.; Harkless, R.V.; Oh, A.; Bowie, K.R.; West-Szymanski, D.C.; Betancourt-Ponce, M.A.; Green, B.D.; Lastra, R.R.; et al. Glucocorticoid receptor modulation decreases ER-positive breast cancer cell proliferation and suppresses wild-type and mutant ER chromatin association. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, T.B.; Voss, T.C.; Sung, M.H.; Baek, S.; John, S.; Hawkins, M.; Grøntved, L.; Schiltz, R.L.; Hager, G.L. Reprogramming the chromatin landscape: Interplay of the estrogen and glucocorticoid receptors at the genomic level. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 5130–5139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinstead, E.E.; Miranda, T.B.; Paakinaho, V.; Baek, S.; Goldstein, I.; Hawkins, M.; Karpova, T.S.; Ball, D.; Mazza, D.; Lavis, L.D.; et al. Steroid Receptors Reprogram FoxA1 Occupancy through Dynamic Chromatin Transitions. Cell 2016, 165, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Nordeen, S.K.; Goleva, E. Estrogen inhibits glucocorticoid action via protein phosphatase 5 (PP5)-mediated glucocorticoid receptor dephosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 24542–24552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.G.; Yue, S.W. Dexamethasone disrupts cytoskeleton organization and migration of T47D human breast cancer cells by modulating the AKT/mTOR/RhoA pathway. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 15, 10245–10250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nesset, K.A.; Perri, A.M.; Mueller, C.R. Frequent promoter hypermethylation and expression reduction of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in breast tumors. Epigenetics 2014, 9, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snider, H.; Villavarajan, B.; Peng, Y.; Shepherd, L.E.; Robinson, A.C.; Mueller, C.R. Region-specific glucocorticoid receptor promoter methylation has both positive and negative prognostic value in patients with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2019, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinyamu, H.K.; Archer, T.K. Estrogen Receptor-Dependent Proteasomal Degradation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor Is Coupled to an Increase in Mdm2 Protein Expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 5867–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, F.H.; Li, Z.B.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.H.; Li, M.; Hu, F. Kaiso represses the expression of glucocorticoid receptor via a methylation-dependent mechanism and attenuates the anti-apoptotic activity of glucocorticoids in breast cancer cells. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- West, D.C.; Kocherginsky, M.; Tonsing-Carter, E.Y.; Dolcen, D.N.; Hosfield, D.J.; Lastra, R.R.; Sinnwell, J.P.; Thompson, K.J.; Bowie, K.R.; Harkless, R.V.; et al. Discovery of a Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Activity Signature Using Selective GR Antagonism in ER-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3433–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan Anderson, T.M.; Ma, S.H.; Raj, G.V.; Cidlowski, J.A.; Helle, T.M.; Knutson, T.P.; Krutilina, R.I.; Seagroves, T.N.; Lange, C.A. Breast tumor kinase (Brk/PTK6) is induced by HIF, glucocorticoid receptor, and PELP1-mediated stress signaling in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez Kerkvliet, C.; Dwyer, A.R.; Diep, C.H.; Oakley, R.H.; Liddle, C.; Cidlowski, J.A.; Lange, C.A. Glucocorticoid receptors are required effectors of TGFβ1-induced p38 MAPK signaling to advanced cancer phenotypes in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.P.; Ueng, S.H.; Chen, S.C.; Chang, Y.S.; Lin, Y.C.; Lo, Y.F.; Chang, H.K.; Chuang, W.Y.; Huang, Y.T.; Cheung, Y.C.; et al. Expression of ROR1 has prognostic significance in triple negative breast cancer. Virchows Arch. 2016, 468, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Cui, B.; Chuang, H.Y.; Yu, J.; Wang-Rodriguez, J.; Tang, L.; Chen, G.; Basak, G.W.; Kipps, T.J. ROR1 is expressed in human breast cancer and associated with enhanced tumor-cell growth. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Yu, J.; Widhopf, G.F.; Fecteau, J.F.; Rassenti, L.Z.; Kipps, T.J. Targeting ROR1 inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3649–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speers, C.; Tsimelzon, A.; Sexton, K.; Herrick, A.M.; Gutierrez, C.; Culhane, A.; Quackenbush, J.; Hilsenbeck, S.; Chang, J.; Brown, P. Identification of novel kinase targets for the treatment of estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 6327–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamar, J.M.; Stern, P.; Liu, H.; Schindler, J.W.; Jiang, Z.G.; Hynes, R.O. The Hippo pathway target, YAP, promotes metastasis through its TEAD-interaction domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2441–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Yuan, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Feng, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yang, C.; Zeng, Y.A.; et al. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling activates TEAD4 to promote breast cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4399–4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Porath, I.; Thomson, M.W.; Carey, V.J.; Ge, R.; Bell, G.W.; Regev, A.; Weinberg, R.A. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008, 40, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Czerwenka, K.; Heinze, G.; Ryffel, M.; Schuster, E.; Witt, A.; Leodolter, S.; Zeillinger, R. Expression of KLF5 is a prognostic factor for disease-free survival and overall survival in patients with breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 2442–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Nie, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, R.; Wu, J.; Qin, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, S.; et al. The interplay between TEAD4 and KLF5 promotes breast cancer partially through inhibiting the transcription of p27Kip1. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 17685–17697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dong, J.; Zou, T.; Du, C.; Li, S.; Chen, C.; Liu, R.; Wang, K. Dexamethasone induces docetaxel and cisplatin resistance partially through up-regulating Krüppel-like factor 5 in triplenegative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 11555–11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikosz, C.A.; Brickley, D.R.; Sharkey, M.S.; Moran, T.W.; Conzen, S.D. Glucocorticoid Receptor-mediated Protection from Apoptosis Is Associated with Induction of the Serine/Threonine Survival Kinase Gene, sgk-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 16649–16654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Chaudhuri, S.; Brickley, D.R.; Pang, D.; Karrison, T.; Conzen, S.D. Microarray Analysis Reveals Glucocorticoid-Regulated Survival Genes That Are Associated with Inhibition of Apoptosis in Breast Epithelial Cells. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Pew, T.; Zou, M.; Pang, D.; Conzen, S.D. Glucocorticoid receptor-induced MAPK phosphatase-1 (MPK-1) expression inhibits paclitaxel-associated MAPK activation and contributes to breast cancer cell survival. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 4117–4124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyeman, A.S.; Jun, W.J.; Proia, D.A.; Kim, C.R.; Skor, M.N.; Kocherginsky, M.; Conzen, S.D. Hsp90 Inhibition Results in Glucocorticoid Receptor Degradation in Association with Increased Sensitivity to Paclitaxel in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Horm. Cancer 2016, 7, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, M.; Chen, F.; Chen, Z.; Fan, W. Glucocorticoids interfere with therapeutic efficacy of paclitaxel against human breast and ovarian xenograft tumors. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, D.; Kocherginsky, M.; Krausz, T.; Kim, S.Y.; Conzen, S.D. Dexamethasone decreases xenograft response to paclitaxel through inhibition of tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, R.; Stringer-Reasor, E.M.; Saha, P.; Kocherginsky, M.; Gibson, J.; Libao, B.; Hoffman, P.C.; Obeid, E.; Merkel, D.E.; Khramtsova, G.; et al. A randomized phase I trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel with or without mifepristone for advanced breast cancer. Springerplus 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Wang, D.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Li, J.; Song, J. Glucocorticoid receptor-IRS-1 axis controls EMT and the metastasis of breast cancers. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 11, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulard, C.; Bittencourt, D.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Gerke, D.S.; Stallcup, M.R. A post-translational modification switch controls coactivator function of histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 1442–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulard, C.; Kim, H.N.; Fang, M.; Kruth, K.; Gagnieux, C.; Gerke, D.S.; Bhojwani, D.; Kim, Y.M.; Kampmann, M.; Stallcup, M.R.; et al. Relapse-associated AURKB blunts the glucocorticoid sensitivity of B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3052–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulard, C.; Baulu, E.; Lee, B.H.; Pufall, M.A.; Stallcup, M.R. Increasing G9a automethylation sensitizes B acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells to glucocorticoid-induced death. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietzen, L.W.; Ahern, T.; Christiansen, P.; Jensen, A.B.; Sørensen, H.T.; Lash, T.L.; Cronin-Fenton, D.P. Glucocorticoid prescriptions and breast cancer recurrence: A Danish nationwide prospective cohort study. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 2419–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, Y.L.; Carlson, N.E.; Chlebowski, R.T.; Aickin, M.; Karen, L.; Ockene, J.K.; Bowen, D.J.; Ritenbaugh, C. Influence of stressors on breast cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermes, G.L.; Delgado, B.; Tretiakova, M.; Cavigelli, S.A.; Krausz, T.; Conzen, S.D.; McClintock, M.K. Social isolation dysregulates endocrine and behavioral stress while increasing malignant burden of spontaneous mammary tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 22393–22398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otranto, M.; Sarrazy, V.; Bonté, F.; Hinz, B.; Gabbiani, G.; Desmoulière, A. The role of the myofibroblast in tumor stroma remodeling. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2012, 6, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandellini, P.; Andriani, F.; Merlino, G.; D’Aiuto, F.; Roz, L.; Callari, M. Complexity in the tumour microenvironment: Cancer associated fibroblast gene expression patterns identify both common and unique features of tumour-stroma crosstalk across cancer types. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2015, 35, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grose, R.; Werner, S.; Kessler, D.; Tuckermann, J.; Huggel, K.; Durka, S.; Reichardt, H.M.; Werner, S. A role for endogenous glucocorticoids in wound repair. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catteau, X.; Simon, P.; Buxant, F.; Noël, J.-C. Expression of the glucocorticoid receptor in breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 5, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X. The role of estrogen receptor beta in breast cancer. Biomark. Res. 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiser, M.J.; Foradori, C.D.; Handa, R.J. Estrogen receptor beta activation prevents glucocorticoid receptor-dependent effects of the central nucleus of the amygdala on behavior and neuroendocrine function. Brain Res. 2010, 1336, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noureddine, L.M.; Trédan, O.; Hussein, N.; Badran, B.; Le Romancer, M.; Poulard, C. Glucocorticoid Receptor: A Multifaceted Actor in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094446

Noureddine LM, Trédan O, Hussein N, Badran B, Le Romancer M, Poulard C. Glucocorticoid Receptor: A Multifaceted Actor in Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(9):4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094446

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoureddine, Lara Malik, Olivier Trédan, Nader Hussein, Bassam Badran, Muriel Le Romancer, and Coralie Poulard. 2021. "Glucocorticoid Receptor: A Multifaceted Actor in Breast Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 9: 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094446

APA StyleNoureddine, L. M., Trédan, O., Hussein, N., Badran, B., Le Romancer, M., & Poulard, C. (2021). Glucocorticoid Receptor: A Multifaceted Actor in Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(9), 4446. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22094446