Poly(chitosan-ester-ether-urethane) Hydrogels as Highly Controlled Genistein Release Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

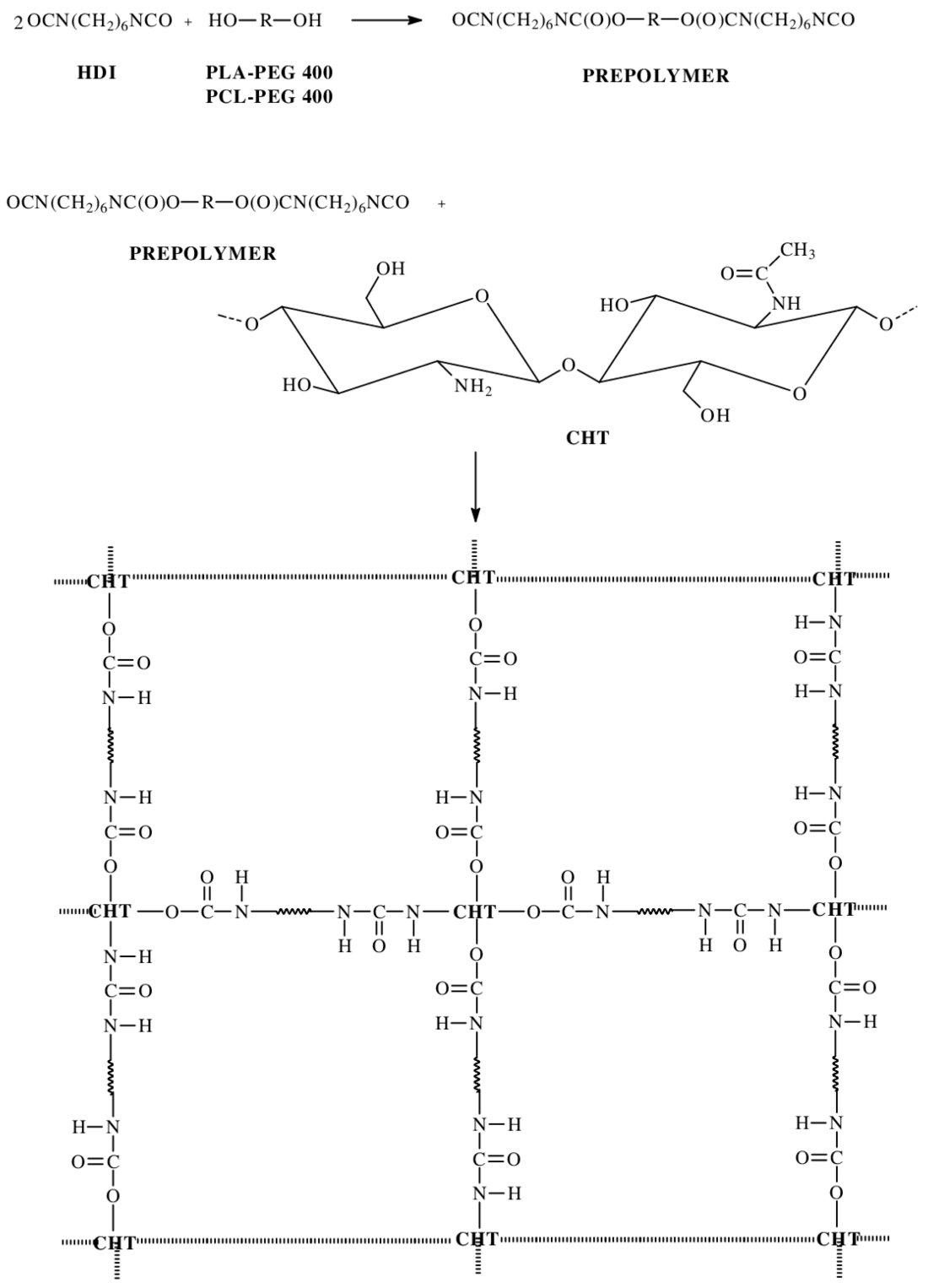

2.1. Synthesis of CL, LA and PEG Copolymers

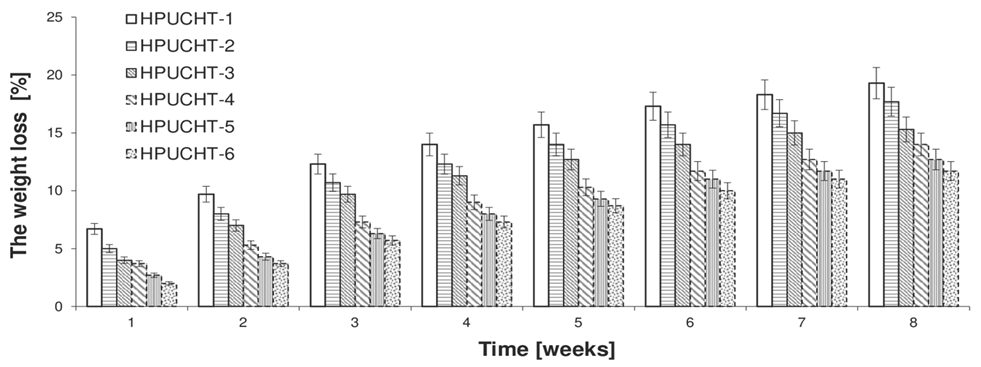

2.2. Swelling and Biodegradation of Hydrogels Studies

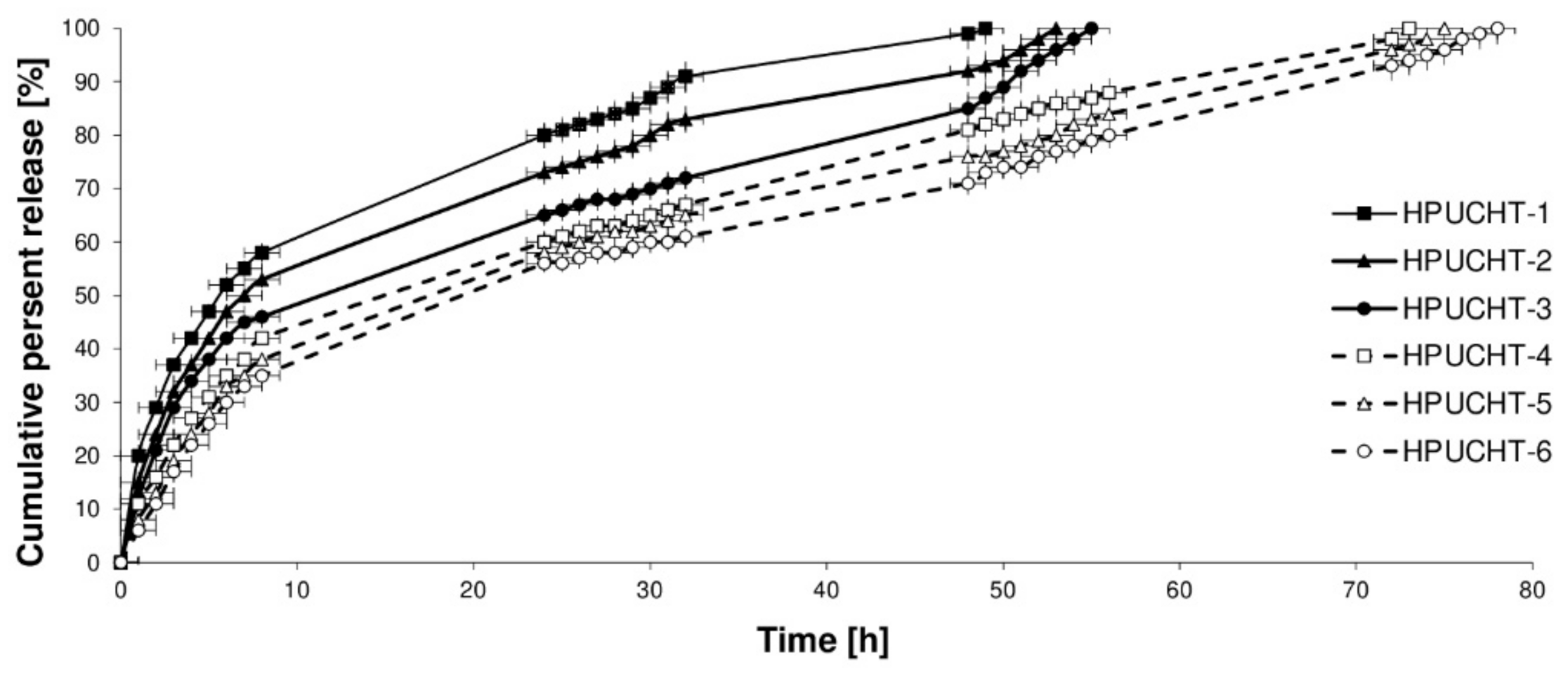

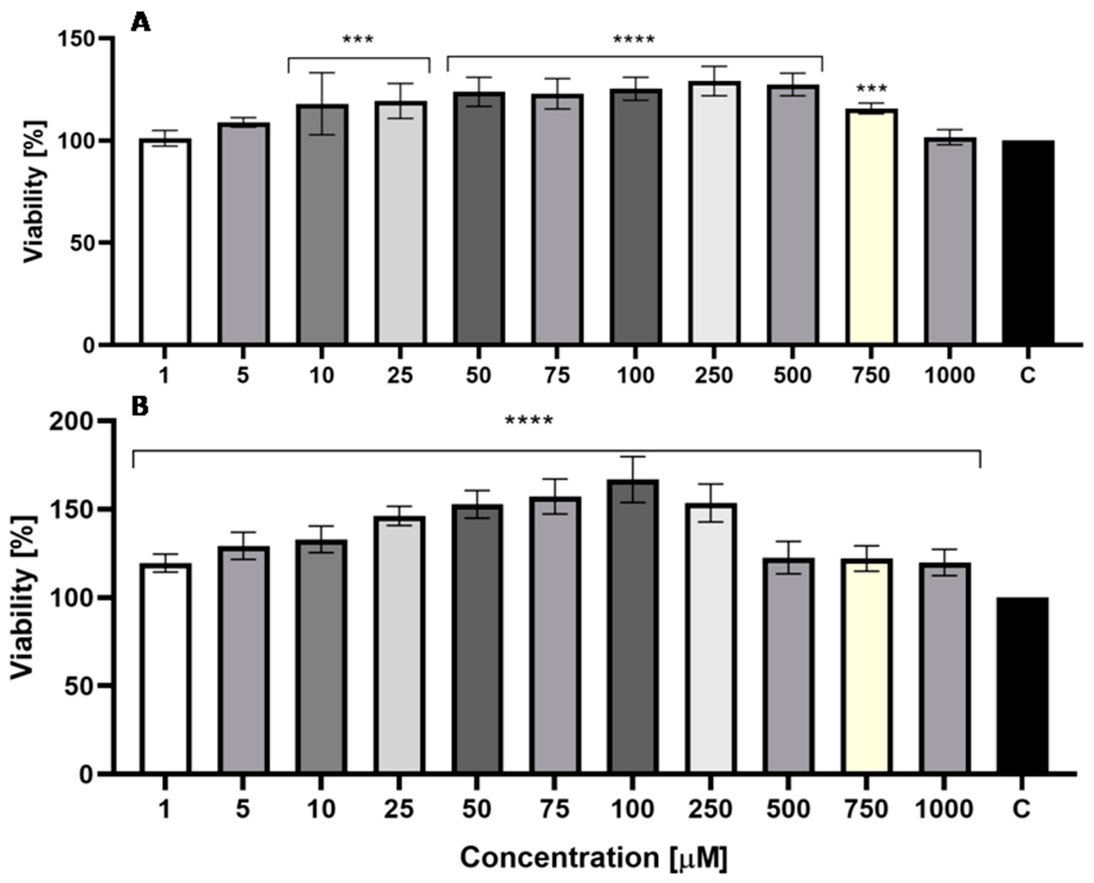

2.3. In Vitro Release Studies of GEN from Hydrogels

2.4. Genotoxic Test

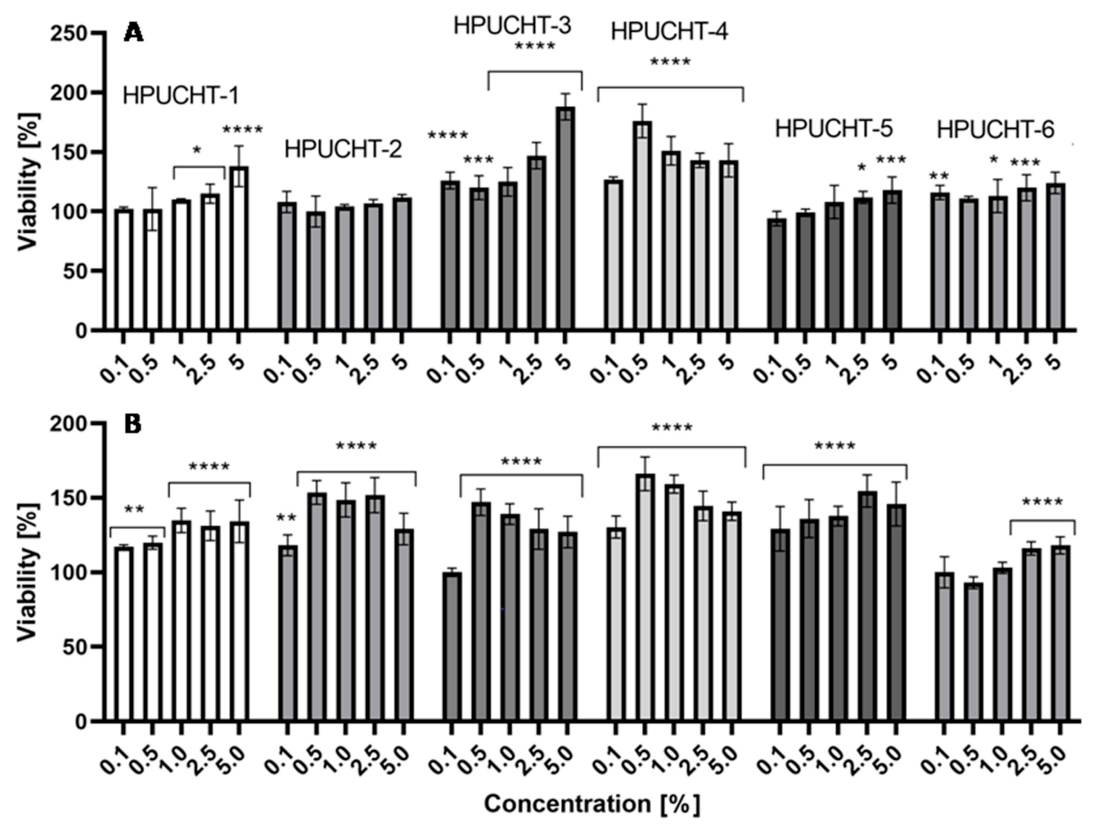

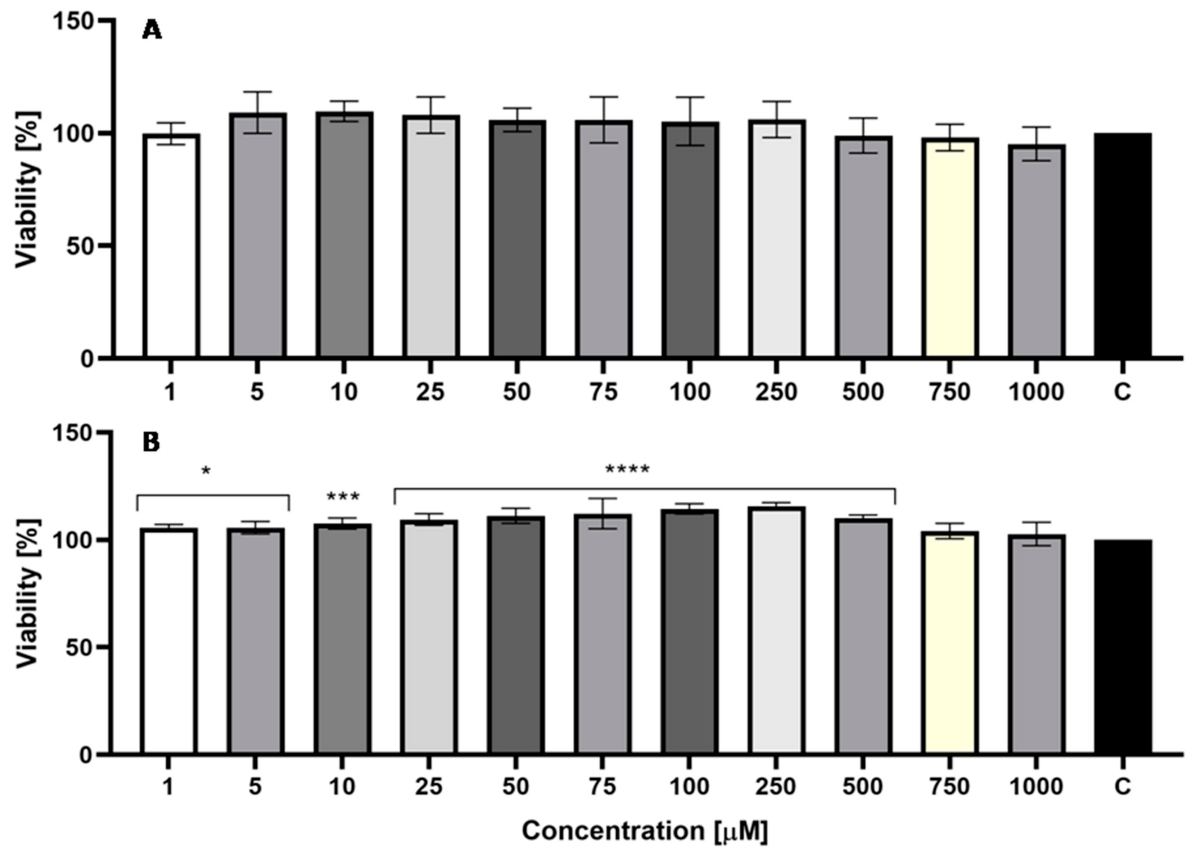

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assessment

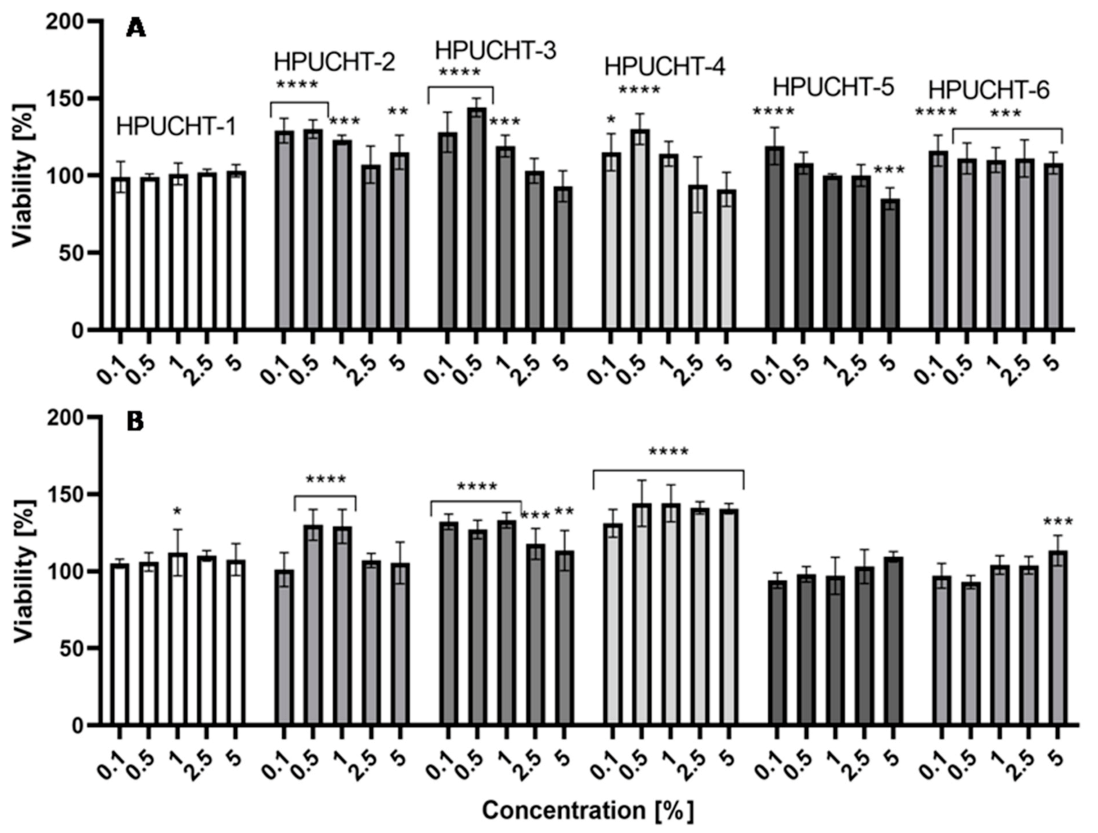

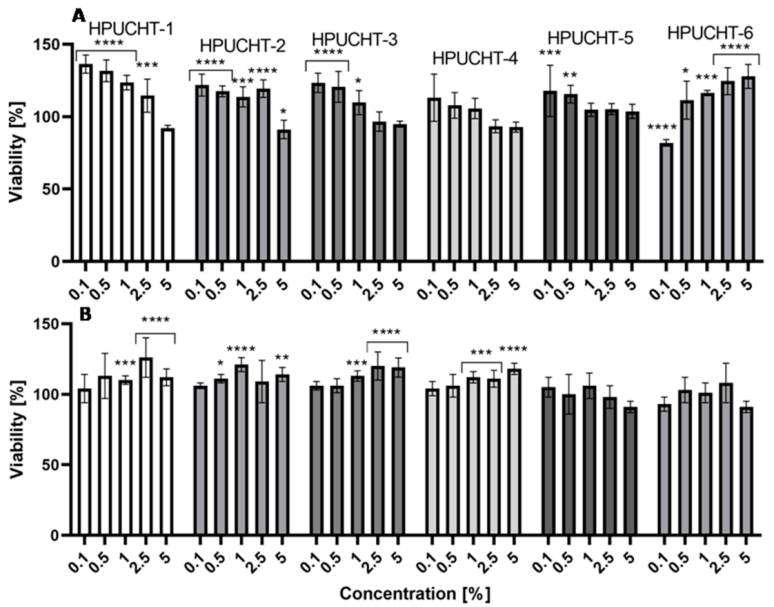

2.5.1. Neutral Red Uptake Assay

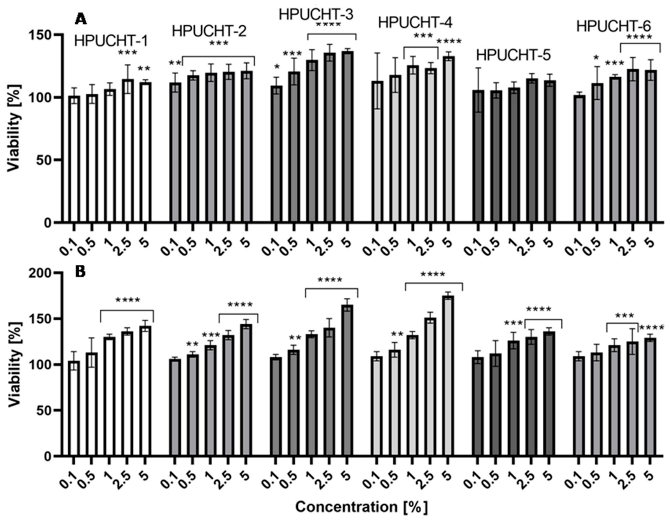

2.5.2. Alamar Blue Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Synthesis of CL, LA and PEG Copolymers

3.3. Spectroscopy Data

3.4. Hydrogels’ Preparation

3.5. Swelling and Biodegradation of Hydrogels Studies

3.6. In Vitro Release Studies of GEN from Hydrogels

3.7. Measurements

3.8. Genotoxic Test

3.9. Cell Culture and Preparation of Hydrogel Extracts

3.10. Cytotoxicity Assays

3.10.1. Neutral Red Uptake Assay

3.10.2. Alamar Blue Assay

3.11. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Sobczak, M. Hydrogel-Based Active Substance Release Systems for Cosmetology and Dermatology Application: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreno, B.; Araviiskaia, E.; Berardesca, E.; Bieber, T.; Hawk, J.; Sanchez-Viera, M.; Wolkenstein, P. The science of dermocosmetics and its role in dermatology. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 28, 1409–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañeta, E.; Stewart, S.; Ervine, M.; Al-Kasasbeh, R.; Donnelly, R.F. Hydrogels for Hydrophobic Drug Delivery. Classification, Synthesis and Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, M.; Betts, D.; Suh, A.; Bui, K.; Kim, L.D.; Cho, H. Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Molecules 2015, 20, 20397–20408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, D.; O’Connor, A.J.; Qiao, G.G.; Ladewig, K. Hydrogels with smart systems for delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017, 14, 879–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, B.C.; Cadinoiu, A.N.; Popa, M.; Desbrieres, J.; Peptu, C.A. Chitosan/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Hydrogels For Entrapment of Drug Loaded Liposomes. Cellulose Chem. Technol. 2014, 48, 485–494. [Google Scholar]

- Musgrave, C.S.A.; Fang, F. Contact Lens Materials: A Materials Science Perspective. Materials 2019, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yu, F.; Zheng, L.; Wang, R.; Yan, W.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Wu, J.; Shi, D.; Zhu, L.; et al. Natural hydrogels for cartilage regeneration: Modification, preparation and application. J. Orthop. Translat. 2018, 17, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, S.; Klar, A.S. Advanced Hydrogels as Wound Dressings. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantha, S.; Pillai, S.; Khayambashi, P.; Upadhyay, A.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, O.; Pham, H.M.; Tran, S.D. Smart Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Materials 2019, 12, 3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyzy, A.; Tomczykowa, M.; Plonska-Brzezinska, M.E. Hydrogels as Potential Nano-, Micro- and Macro-Scale Systems for Controlled Drug Delivery. Materials 2020, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalache, C.; Rata, D.M.; Cadinoiu, A.N.; Patras, X.; Bacaita, S.E.; Popa, M.; Atanase, L.I.; Daraba, O.M. Bupivacaine-loaded chitosan hydrogels for topical anesthesia in dentistry. Polym. Int. 2020, 69, 1152–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mooney, D.J. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soppimath, K.S.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Dave, A.M.; Kumbar, S.G.; Rudzinski, W.E. Stimulus-responsive “smart” hydrogels as novel drug delivery systems. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2002, 28, 957–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombino, S.; Servidio, C.; Curcio, F.; Cassano, R. Strategies for Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogel Design in Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, M.E.; Stephenson, R.E.; Murphy, A.C.; Oldenkamp, H.F.; Singh, A.; Peppas, N.A. Engineered microscale hydrogels for drug delivery, cell therapy, and sequencing. Biomed. Microdevices 2019, 21, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanaswamy, R.; Torchilin, V.P. Hydrogels and Their Applications in Targeted Drug Delivery. Molecules 2019, 24, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, M.E.; Ochoa Andrade, A.; Ares, G.; Russo, F.; Jiménez-Kairuz, Á. Bioadhesive hydrogels for cosmetic applications. Int J. Cosmet. Sci. 2015, 37, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Kim, J.C.; Hwang, S.J. Hydrogel patches containing triclosan for acne treatment. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2003, 56, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilforoushzadeh, M.A.; Amirkhani, M.A.; Zarrintaj, P.; Salehi Moghaddam, A.; Mehrabi, T.; Alavi, S.; MollapourSisakht, M. Skin care and rejuvenation by cosmeceutical facial mask. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Sun, M.; Bu, Y.; Luo, F.; Lin, C.; Lin, Z.; Weng, Z.; Yang, F.; Wu, D. Microcapsule-embedded hydrogel patches for ultrasound responsive and enhanced transdermal delivery of diclofenac sodium. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 2330–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, J.; Brandl, F.P.; Goepferich, A.M. Hydrogel wound dressings for bioactive treatment of acute and chronic wounds. Eur. Polym. J. 2018, 100, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, D.; Martina, V.; Mocchi, R.; Rauso, R.; Zerbinati, U.; Cipolla, G.; Zerbinati, N. Chemical Characterization of Hydrogels Crosslinked with Polyethylene Glycol for Soft Tissue Augmentation. Open. Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaia, L.; Coneac, G.; Olariu, I.; Vlaia, V.; Lupuleasa, D. Cellulose-Derivatives-Based Hydrogels as Vehicles for Dermal and Transdermal Drug Delivery. In Emerging Concepts in Analysis and Applications of Hydrogels; Majee, S.B., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cen, L.; Liu, W.; Cui, L.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y. Collagen tissue engineering: Development of novel biomaterials and applications. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 63, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Ji, K.; Shih, T.Y.; Haddad, A.; Giatsidis, G.; Mooney, D.J.; Orgill, D.P.; Nabzdyk, C.S. Injectable Shape-Memorizing Three-Dimensional Hyaluronic Acid Cryogels for Skin Sculpting and Soft Tissue Reconstruction. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Kulkarni, K.; Zhu, W.; Hu, M. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of genistein: Mechanistic studies on its ADME. Anti-Cancer Agents Med. Chem. 2012, 12, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, D.C.; Piazza, C.; Melilli, B.; Drago, F.; Salomone, S. Isoflavones: Estrogenic activity, biological effect and bioavailability. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 38, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuseran, H.; Hartoyo, E.; Nurseta, T.; Kalim, H. Molecular docking of genistein on estrogen receptors, promoter region of BCLX, caspase-3, Ki-67, cyclin D1, and telomere activity. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2018, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, M.J. Estrogens and aging skin. Dermato-Endocrinology 2013, 5, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horng, H.C.; Chang, W.H.; Yeh, C.C.; Huang, B.S.; Chang, C.P.; Chen, Y.J.; Tsui, K.H.; Wang, P.H. Estrogen Effects on Wound Healing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrera, N.; Pizzino, G.; D’Anna, R.; Vaccaro, M.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Bitto, A. Dietary Management of Skin Health: The Role of Genistein. Nutrients 2017, 9, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, N.; Yan, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, K.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Q.M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.D. Recent advances in the anti-aging effects of phytoestrogens on collagen, water content, and oxidative stress. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidenbörner, M.; Hindorf, H.; Jha, H.C.; Tsotsonos, P.; Egge, H. Antifungal activity of isoflavonoids in different reduced stages on Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 801–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, W.G.; Suh, J.W. Talosians A and B: New Isoflavonol Glycosides with Potent Antifungal Activity from Kitasatosporakifunensine MJM341. J. Antibiot. 2006, 59, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Landauer, M.R.; Foriska, M.A.; Ledney, G.D. Antibacterial activity of the soy isoflavone genistein. J. Basic Microbiol. 2006, 46, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulanowska, K.; Tkaczyk, A.; Konopa, G.; Węgrzyn, G. Differential antibacterial activity of genistein arising from global inhibition of DNA, RNA and protein synthesis in some bacterial strains. Arch. Microbiol. 2006, 184, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, S.; Dai, X.; Chen, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, J. Genistein inhibits proliferation and functions of hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Burns 2009, 35, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isoherranen, K.; Punnonen, K.; Jansen, C.; Uotila, P. Ultraviolet irradiation induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in keratinocytes. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999, 140, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iovine, B.; Iannella, M.L.; Gasparri, F.; Monfrecola, G.; Bevilacqua, M.A. Synergic Effect of Genistein and Daidzein on UVB-Induced DNA Damage: An Effective Photoprotective Combination. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 692846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Saladi, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Palep, S.R.; Moore, J.; Phelps, R.; Shyong, E.; Lebwohl, M.G. Isoflavone genistein: Photoprotection and clinical implications in dermatology. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3811S–3819S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terra, V.A.; Souza-Neto, F.P.; Frade, M.A.; Ramalho, L.N.; Andrade, T.A.; Pasta, A.A.; Conchon, A.C.; Guedes, F.A.; Luiz, R.C.; Cecchini, R.; et al. Genistein prevents ultraviolet B radiation-induced nitrosative skin injury and promotes cell proliferation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2015, 144, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marini, H.; Polito, F.; Altavilla, D.; Irrera, N.; Minutoli, L.; Calò, M.; Adamo, E.B.; Vaccaro, M.; Squadrito, F.; Bitto, A. Genistein aglycone improves skin repair in an incisional model of wound healing: A comparison with raloxifene and oestradiol in ovariectomized rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 160, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polito, F.; Marini, H.; Bitto, A.; Irrera, N.; Vaccaro, M.; Adamo, E.B.; Micali, A.; Squadrito, F.; Minutoli, L.; Altavilla, D. Genistein aglycone, a soy-derived isoflavone, improves skin changes induced by ovariectomy in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanivel, G.; Dong-Kug, C. Current application of phytocompound-based nanocosmeceuticals for beauty and skin therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 1987–2007. [Google Scholar]

- de Vargas, B.A.; Bidone, J.; Oliveira, L.K.; Koester, L.S.; Bassani, V.L.; Teixeira, H.F. Development of topical hydrogels containing genistein-loaded nanoemulsions. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2012, 8, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.H.; Kang, M.J.; Lee, J.; Choi, Y.W. Influence of liposome type and skin model on skin permeation and accumulation properties of genistein. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2010, 31, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, J.; Göpferich, A. Mathematical modeling of bioerodible, polymeric drug delivery systems. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 48, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.; Murthy, P.N.; Nath, L.; Chowdhury, P. Kinetic modeling on drug release from controlled drug delivery systems. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2010, 67, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Ho, C.T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Dong, M.; Huang, Q. Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Genistein-Loaded Zein/Carboxymethyl Chitosan Nanoparticles with Improved Water Dispersibility, Enhanced Antioxidant Activity, and Controlled Release Property. Foods 2020, 9, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, L.M.; de Fátima Reis, C.; Maione-Silva, L.; Anjos, J.L.V.; Alonso, A.; Serpa, R.C.; Marreto, R.N.; Lima, E.M.; Taveira, S.F. Impact of lipid dynamic behavior on physicalstability, in vitro release and skin permeation of genistein-loaded lipid nanoparticles. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zampieri, A.L.; Ferreira, F.S.; Resende, E.C.; Gaeti, M.P.; Diniz, D.G.; Taveira, S.F.; Lima, E.M. Biodegradable polymeric nanocapsules based on poly(DL-lactide) for genistein topical delivery: Obtention, characterization and skin permeation studies. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2013, 9, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenta, D.F.; de Mattos, C.B.; Misturini, F.D.; Koester, L.S.; Bassani, V.L.; Simões, C.M.; Teixeira, H.F. Factorial design applied to the optimization of lipid composition of topical antiherpetic nanoemulsions containing isoflavone genistein. Int. J. Nanomed. 2014, 9, 4737–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nemitz, M.C.; von Poser, G.L.; Teixeira, H.F. In vitro skin permeation/retention of daidzein, genistein and glycitein from a soybean isoflavone rich fraction-loaded nanoemulsions and derived hydrogels. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2019, 51, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Peng, J.; Lei, D.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G. Optimization of genistein solubilization byκ-carrageenan hydrogelusing response surface methodology. Food Sci. Hum. Well 2013, 2, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ding, L.; Yan, X.; Zhao, D.; Shao, N.; Ye, X.; Cheng, Y. Inclusioncomplexes of isoflavones with two commercially available dendrimers: Solubility, stability, structures, releasebehaviors, cytotoxicity, and anti-oxidant activities. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 421, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.R.; Hung, C.F.; Lin, Y.K.; Fang, J.Y. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of topical delivery and potential dermal use of soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobczak, M. Enzyme-Catalyzed Ring-Opening Polymerization of Cyclic Esters in the Presence of Poly(ethylene glycol). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 125, 3602–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, U.; Oledzka, E.; Zgadzaj, A.; Bauer, M.; Sobczak, M. A Novel Delivery System for the Controlled Release~of Antimicrobial Peptides: Citropin 1.1 and Temporin A. Polymers 2018, 10, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, U.; Sobczak, M.; Oledzka, E.; Combes, C. Effect of ionic liquids on the structural, thermal, and in vitro degradation properties of poly(epsilon-caprolactone) synthesized in the presence of Candida antarctica lipase B. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, A.K.; Mittal, V.; Singh, N.; Dash, D.; Malik, S.; Kumar, M.; Maiti, P. Polyurethane-grafted chitosan as new biomaterials for con-trolled drug delivery. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2654–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, H.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, B. Micellar emulsions composed of mPEG-PCL/MCT as novel nanocarriers for systemic delivery of genistein: A comparative study with micelles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 6175–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cheng, Q.; Qin, W.; Yu, Y.; Li, G.; Wu, J.; Zhuo, L. Preparation and Characterization of PEG-PLA Genistein Micelles Using a Modified Emulsion -Evaporation Method. J. Nanomater. 2020, 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kasiński, A.; Zielińska-Pisklak, M.; Oledzka, E.; Nałęcz-Jawecki, G.; Drobniewska, A.; Sobczak, M. Hydrogels Based on Poly(Ether-Ester)s as Highly Controlled 5-Fluorouracil Delivery Systems-Synthesis and Characterization. Materials 2021, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Oki, I.; Kato, T.; Shinagawa, H. Evaluation of the new system (umu-test) for the detection of environmental mutagens and carcinogens. Mutat. Res. 1985, 147, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization. Water Quality-Determination of the Genotoxicity of Water and Waste Water Using the Umu-Test; International Standard. ISO/FDIS 13829: 2000; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Ziemlewska, A.; Nizioł-Łukaszewska, Z.; Bujak, T. Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity of Medicago sativa L. Seeds and Herb Extract on Skin Cells. Biores. Open Access 2020, 9, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, B.; Page, M.; Noel, C. A new fluorometric assay for cytotoxicity measurements in-vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 1993, 3, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Sample | Molar Ratio a | Yield [%] | Mnb [g/mol] | Đb | % mol CL or LA c | % mol PEG c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA-PEG-1 | 20:1 | 77 | 3200 | 1.69 | 79.7 | 20.3 |

| PLA-PEG-2 | 25:1 | 72 | 3400 | 1.57 | 84.9 | 15.1 |

| PLA-PEG-3 | 30:1 | 69 | 3500 | 1.62 | 88.3 | 11.7 |

| PCL-PEG-1 | 30:1 | 88 | 3400 | 1.48 | 80.4 | 19.6 |

| PCL-PEG-2 | 35:1 | 80 | 3500 | 1.43 | 84.3 | 15.7 |

| PCL-PEG-3 | 40:1 | 76 | 3700 | 1.52 | 88.9 | 11.1 |

| Sample | PLA-PEG | PCL-PEG | MSR [%] a | MSR [%] b | MSR [%] c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPUCHT-1 | PLA-PEG-1 (80:20) | - | 375 ± 17 | 412 ± 18 | 421 ± 18 |

| HPUCHT-2 | PLA-PEG-2 (85:15) | - | 311 ± 14 | 341 ± 15 | 348 ± 15 |

| HPUCHT-3 | PLA-PEG-3 (88:12) | - | 284 ± 13 | 311 ± 13 | 326 ± 14 |

| HPUCHT-4 | - | PCL-PEG-1 (80:20) | 297 ± 14 | 328 ± 15 | 333 ± 15 |

| HPUCHT-5 | - | PCL-PEG-2 (84:16) | 258 ± 11 | 284 ± 13 | 287 ± 13 |

| HPUCHT-6 | - | PCL-PEG-3 (89:11) | 211 ± 11 | 232 ± 11 | 243 ± 12 |

| No. | Zero-Order Model | First-Order Model | Korsmeyer-Peppas Model | GEN Transport Mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | R2 | R2 | n | ||

| HPUCHT-1 | 0.847 | 0.915 | 0.998 | 0.516 | non-Fickian transport |

| HPUCHT-2 | 0.873 | 0.940 | 0.995 | 0.609 | non-Fickian transport |

| HPUCHT-3 | 0.921 | 0.868 | 0.944 | 0.452 | non-Fickian transport |

| HPUCHT-4 | 0.923 | 0.913 | 0.976 | 0.488 | non-Fickian transport |

| HPUCHT-5 | 0.925 | 0.869 | 0.968 | 0.553 | non-Fickian transport |

| HPUCHT-6 | 0.941 | 0.831 | 0.957 | 0.597 | non-Fickian transport |

| −S9 * | +S9 ** | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G ± SD | IR ± SD | G ± SD | IR ± SD | |

| MS H-1 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.94 ± 0.07 | 0.95 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.04 |

| MS H-2 | 1.05 ± 0.05 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.98 ± 0.05 | 0.85 ± 0.20 |

| MS H-3 | 1.06 ± 0.08 | 0.81 ± 0.13 | 1.03 ± 0.06 | 0.96 ± 0.20 |

| MS H-4 | 0.99 ± 0.04 | 0.94 ± 0.08 | 1.10 ± 0.24 | 0.85 ± 0.34 |

| MS H-5 | 1.05 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.17 | 1.07 ± 0.14 | 0.88 ± 0.26 |

| MS H-6 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.10 | 1.03 ± 0.15 | 0.90 ± 0.27 |

| Positive contol | 0.98 ± 0.01 | 7.77 ± 0.18 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 4.52 ± 0.13 |

| Negative control | 1.01 ± 0.07 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.00 ± 0.10 | 1.02 ± 0.25 |

| Solvent control | 1.02 ± 0.04 | 1.04 ± 0.14 | 0.74 ± 0.08 | 1.13 ± 0.20 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zagórska-Dziok, M.; Kleczkowska, P.; Olędzka, E.; Figat, R.; Sobczak, M. Poly(chitosan-ester-ether-urethane) Hydrogels as Highly Controlled Genistein Release Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073339

Zagórska-Dziok M, Kleczkowska P, Olędzka E, Figat R, Sobczak M. Poly(chitosan-ester-ether-urethane) Hydrogels as Highly Controlled Genistein Release Systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(7):3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073339

Chicago/Turabian StyleZagórska-Dziok, Martyna, Patrycja Kleczkowska, Ewa Olędzka, Ramona Figat, and Marcin Sobczak. 2021. "Poly(chitosan-ester-ether-urethane) Hydrogels as Highly Controlled Genistein Release Systems" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 7: 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073339

APA StyleZagórska-Dziok, M., Kleczkowska, P., Olędzka, E., Figat, R., & Sobczak, M. (2021). Poly(chitosan-ester-ether-urethane) Hydrogels as Highly Controlled Genistein Release Systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(7), 3339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22073339