Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

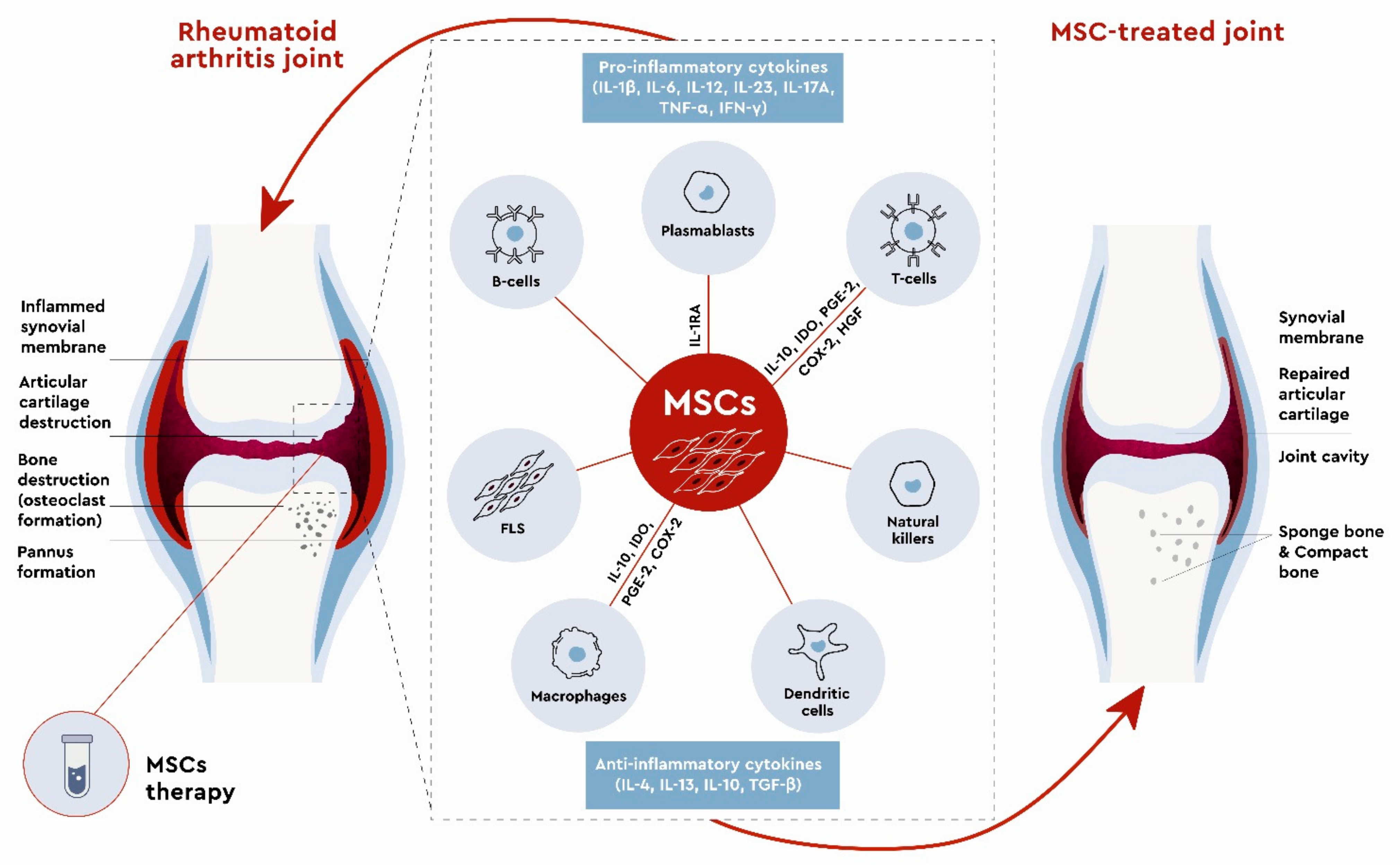

2. Current Approaches in RA Treatment

3. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in RA Treatment

3.1. In Vitro Studies

3.2. Preclinical Studies

3.3. Clinical Studies

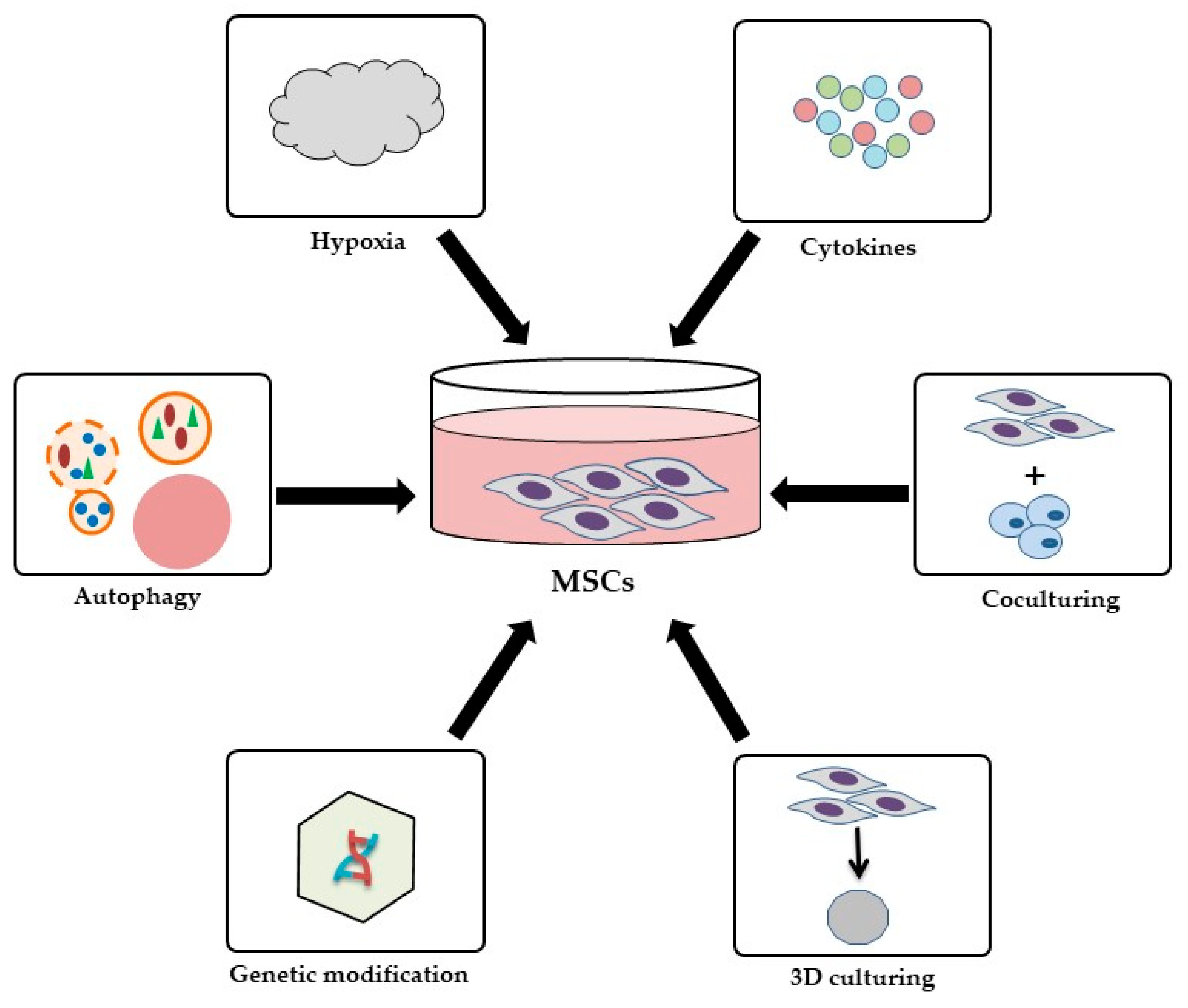

3.4. Strategies to Improve the Therapeutic Effects of MSCs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aletaha, D.; Smolen, J.S. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: A review. JAMA 2018, 320, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myasoedova, E.; Davis, J.; Matteson, E.L.; Crowson, C.S. Is the epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis changing? Results from a population-based incidence study, 1985–2014. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firestein, G.S.; McInnes, I.B. Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2017, 46, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smolen, J.S.; Aletaha, D.; Barton, A.; Burmester, G.R.; Emery, P.; Firestein, G.S.; Kavanaugh, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Solomon, D.H.; Strand, V.; et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D.; Nossent, J.; Pavlos, N.J.; Xu, J. Rheumatoid arthritis: Pathological mechanisms and modern pharmacologic therapies. Bone Res. 2018, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-J.; Anzaghe, M.; Schülke, S. Update on the pathomechanism, diagnosis, and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis. Cells 2020, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altawil, R.; Saevarsdottir, S.; Wedrén, S.; Alfredsson, L.; Klareskog, L.; Lampa, J. Remaining Pain in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated With Methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 1061–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, J.A.; Saag, K.G.; Bridges, S.L., Jr.; Akl, E.A.; Bannuru, R.R.; Sullivan, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.; McNaughton, C.; Osani, M.; Shmerling, R.H.; et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Santalla, M.; Bueren, J.A.; Garin, M.I. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-based therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: An update on preclinical studies. EBioMedicine 2021, 69, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansboro, S.; Roelofs, A.J.; De Bari, C. Mesenchymal stem cells for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: Immune modulation, repair or both? Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, M.E.; Fibbe, W.E. Mesenchymal stromal cells: Sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.; Li, R.; Liu, T.; Yang, L.; Yin, G.; Xie, Q. Immunomodulatory Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccelli, A.; de Rosbo, N.K. The immunomodulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells: Mode of action and pathways. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1351, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.-C.; Kang, K.-S. Functional enhancement strategies for immunomodulation of mesenchymal stem cells and their therapeutic application. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wong, C.W.; Han, M.; Farhoodi, H.P.; Liu, G.; Liu, Y.; Liao, W.; Zhao, W. Meta-analysis of preclinical studies of mesenchymal stromal cells to treat rheumatoid arthritis. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Álvaro-Gracia, J.M.; Jover, J.A.; García-Vicuña, R.; Carreño, L.; Alonso, A.; Marsal, S.; Blanco, F.; Martínez-Taboada, V.M.; Taylor, P.; Martín-Martín, C. Intravenous administration of expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells in refractory rheumatoid arthritis (Cx611): Results of a multicentre, dose escalation, randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled phase Ib/IIa clinical trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, J.C.; Shin, I.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, S.K.; Kang, B.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Jo, J.Y.; Yoon, E.J.; Choi, H.J. Safety of intravenous infusion of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells in animals and humans. Stem Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 1297–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadmanfar, S.; Labibzadeh, N.; Emadedin, M.; Jaroughi, N.; Azimian, V.; Mardpour, S.; Kakroodi, F.A.; Bolurieh, T.; Hosseini, S.E.; Chehrazi, M. Intra-articular knee implantation of autologous bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells in rheumatoid arthritis patients with knee involvement: Results of a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1/2 clinical trial. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoryani, M.; Shariati-Sarabi, Z.; Tavakkol-Afshari, J.; Ghasemi, A.; Poursamimi, J.; Mohammadi, M. Amelioration of clinical symptoms of patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis following treatment with autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: A successful clinical trial in Iran. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Cong, X.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Bai, B.; Li, Y.; Bai, W.; Li, M.; Ji, H. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy for patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: Safety and efficacy. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 3192–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Li, S.; Li, M.; Shi, J.; Bai, W.; Wang, Q.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Y. Efficacy and safety of umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients: A prospective phase I/II study. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2019, 13, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, E.H.; Lim, H.s.; Lee, S.; Roh, K.; Seo, K.W.; Kang, K.S.; Shin, K. Intravenous Infusion of Umbilical Cord Blood Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Phase Ia Clinical Trial. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatzidionysiou, K.; Emamikia, S.; Nam, J.; Ramiro, S.; Smolen, J.; van der Heijde, D.; Dougados, M.; Bijlsma, J.; Burmester, G.; Scholte, M. Efficacy of glucocorticoids, conventional and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: A systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoli, D.J.; Ma, E.H.; Roy, D.; Russo, M.; Bridon, G.; Avizonis, D.; Jones, R.G.; St-Pierre, J. Methotrexate elicits pro-respiratory and anti-growth effects by promoting AMPK signaling. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Aune, T.M. Methotrexate and its mechanisms of action in inflammatory arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.; Hemshekhar, M.; Thushara, R.M.; Sundaram, M.S.; NaveenKumar, S.K.; Naveen, S.; Devaraja, S.; Somyajit, K.; West, R.; Nayaka, S.C. Methotrexate promotes platelet apoptosis via JNK-mediated mitochondrial damage: Alleviation by N-acetylcysteine and N-acetylcysteine amide. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solomon, D.H.; Glynn, R.J.; Karlson, E.W.; Lu, F.; Corrigan, C.; Colls, J.; Xu, C.; MacFadyen, J.; Barbhaiya, M.; Berliner, N.; et al. Adverse Effects of Low-Dose Methotrexate: A Randomized Trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.M.; Pratt, A.G.; Isaacs, J.D. Mechanism of action of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis, and the search for biomarkers. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Cronstein, B.N. Understanding the mechanisms of action of methotrexate. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2007, 65, 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ede, A.E.; Laan, R.F.; Rood, M.J.; Huizinga, T.W.; Van De Laar, M.A.; Denderen, C.J.V.; Westgeest, T.A.; Romme, T.C.; De Rooij, D.J.R.; Jacobs, M.J. Effect of folic or folinic acid supplementation on the toxicity and efficacy of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: A forty-eight-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. Off. J. Am. Coll. Rheumatol. 2001, 44, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, J.A. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, ITC1–ITC16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.B.M.; Bijlsma, J.W.J.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Kerschbaumer, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Sepriano, A.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; de Wit, M.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 79, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Scott, D.L.; Wolfe, F.; Huizinga, T.W. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010, 376, 1094–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.T.K.; Mok, C.C.; Cheung, T.T.; Kwok, K.Y.; Yip, R.M.L. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2019 updated consensus recommendations from the Hong Kong Society of Rheumatology. Clin. Rheumatol. 2019, 38, 3331–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daien, C.I.; Charlotte, H.; Combe, B.; Landewe, R. Non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions in patients with early arthritis: A systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. RMD Open 2017, 3, e000404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; Landewé, R.; Bijlsma, J.; Burmester, G.; Chatzidionysiou, K.; Dougados, M.; Nam, J.; Ramiro, S.; Voshaar, M.; van Vollenhoven, R.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 960–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surjit, M.; Ganti, K.P.; Mukherji, A.; Ye, T.; Hua, G.; Metzger, D.; Li, M.; Chambon, P. Widespread negative response elements mediate direct repression by agonist-liganded glucocorticoid receptor. Cell 2011, 145, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coutinho, A.E.; Chapman, K.E. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 335, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchetti, S.; Migliorati, G.; Bruscoli, S.; Riccardi, C. Defining the role of glucocorticoids in inflammation. Clin. Sci. 2018, 132, 1529–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ahmet, A.; Ward, L.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Mandelcorn, E.D.; Leigh, R.; Brown, J.P.; Cohen, A.; Kim, H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yasir, M.; Goyal, A.; Bansal, P.; Sonthalia, S. Corticosteroid Adverse Effects. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Combe, B.; Landewe, R.; Daien, C.I.; Hua, C.; Aletaha, D.; Álvaro-Gracia, J.M.; Bakkers, M.; Brodin, N.; Burmester, G.R.; Codreanu, C. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 948–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heide, A.; Jacobs, J.W.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Heurkens, A.H.; van Booma-Frankfort, C.; van der Veen, M.J.; Haanen, H.C.; Hofman, D.M.; van Albada-Kuipers, G.A.; ter Borg, E.J.; et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with "second-line" antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996, 124, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, K.; Kuzawińska, O.; Bałkowiec-Iskra, E. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors–state of knowledge. Arch. Med. Sci. AMS 2014, 10, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpétuo, I.P.; Caetano-Lopes, J.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Campanilho-Marques, R.; Ponte, C.; Canhão, H.; Ainola, M.; Fonseca, J.E. Effect of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy on osteoclasts precursors in rheumatoid arthritis. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2690402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, P.; Mueller, R.B. Treatment with biologicals in rheumatoid arthritis: An overview. Rheumatol. Ther. 2017, 4, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- den Broeder, A.A.; van Herwaarden, N.; van den Bemt, B.J. Therapeutic drug monitoring of biologicals in rheumatoid arthritis: A disconnect between beliefs and facts. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, J.C.; Bononi, I.; Puozzo, A.; Govoni, M.; Foschi, V.; Lanza, G.; Gafà, R.; Gaboriaud, P.; Touzé, F.A.; Selvatici, R.; et al. Merkel Cell Carcinomas Arising in Autoimmune Disease Affected Patients Treated with Biologic Drugs, Including Anti-TNF. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 3929–3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersson, K.M.; Cavallini, N.F.; Hu, D.; Brisslert, M.; Cialic, R.; Valadi, H.; Erlandsson, M.C.; Silfverswärd, S.; Pullerits, R.; Kuchroo, V.K. Pathogenic transdifferentiation of Th17 cells contribute to perpetuation of rheumatoid arthritis during anti-TNF treatment. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romas, E.; Sims, N.A.; Hards, D.K.; Lindsay, M.; Quinn, J.W.; Ryan, P.F.; Dunstan, C.R.; Martin, T.J.; Gillespie, M.T. Osteoprotegerin reduces osteoclast numbers and prevents bone erosion in collagen-induced arthritis. Am. J. Pathol. 2002, 161, 1419–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mann, D.L. Innate immunity and the failing heart: The cytokine hypothesis revisited. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mok, C.C. Rituximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: An update. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2014, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Langdon, K.; Haleagrahara, N. Regulatory T-cell dynamics with abatacept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 37, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuyo, S.; Nakayamada, S.; Iwata, S.; Kubo, S.; Saito, K.; Tanaka, Y. Abatacept therapy reduces CD28+ CXCR5+ follicular helper-like T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kishimoto, T.; Kang, S.; Tanaka, T. IL-6: A new era for the treatment of autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Innov. Med. 2015, 26, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, M.C.; Durez, P.; Richards, H.B.; Supronik, J.; Dokoupilova, E.; Mazurov, V.; Aelion, J.A.; Lee, S.-H.; Codding, C.E.; Kellner, H. Efficacy and safety of secukinumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A phase II, dose-finding, double-blind, randomised, placebo controlled study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.A.; Churchill, M.; Flores-Suarez, L.F.; Cardiel, M.H.; Wallace, D.; Martin, R.; Phillips, K.; Kaine, J.L.; Dong, H.; Salinger, D. A phase Ib multiple ascending dose study evaluating safety, pharmacokinetics, and early clinical response of brodalumab, a human anti-IL-17R antibody, in methotrexate-resistant rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nam, J.L.; Takase-Minegishi, K.; Ramiro, S.; Chatzidionysiou, K.; Smolen, J.S.; van der Heijde, D.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Burmester, G.R.; Dougados, M.; Scholte-Voshaar, M.; et al. Efficacy of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: A systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2017, 76, 1113–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamilloux, Y.; El Jammal, T.; Vuitton, L.; Gerfaud-Valentin, M.; Kerever, S.; Sève, P. JAK inhibitors for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, P.; De Cock, D.; Corluy, L.; Joos, R.; Langenaken, C.; Taelman, V.; Raeman, F.; Ravelingien, I.; Vandevyvere, K.; Lenaerts, J. Methotrexate in combination with other DMARDs is not superior to methotrexate alone for remission induction with moderate-to-high-dose glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis after 16 weeks of treatment: The CareRA trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2015, 74, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, Y.; Tanaka, T. Interleukin 6 and rheumatoid arthritis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gertel, S.; Mahagna, H.; Karmon, G.; Watad, A.; Amital, H. Tofacitinib attenuates arthritis manifestations and reduces the pathogenic CD4 T cells in adjuvant arthritis rats. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 184, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, T.T.; McInnes, I.B. Future therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis? In Seminars in Immunopathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.C.; Keystone, E.C.; Van Der Heijde, D.; Weinblatt, M.E.; del Carmen Morales, L.; Reyes Gonzaga, J.; Yakushin, S.; Ishii, T.; Emoto, K.; Beattie, S. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmester, G.R.; Kremer, J.M.; Van den Bosch, F.; Kivitz, A.; Bessette, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Othman, A.A.; Pangan, A.L.; Camp, H.S. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 2503–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, J.; Li, Z.G.; Hall, S.; Fleischmann, R.; Genovese, M.; Martin-Mola, E.; Isaacs, J.D.; Gruben, D.; Wallenstein, G.; Krishnaswami, S.; et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 159, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crofford, L.J. Use of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.F.; Jobanputra, P.; Barton, P.; Bryan, S.; Fry-Smith, A.; Harris, G.; Taylor, R.S. Cyclooxygenase-2 selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (etodolac, meloxicam, celecoxib, rofecoxib, etoricoxib, valdecoxib and lumiracoxib) for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol. Assess. 2008, 12, 1–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knut, L. Radiosynovectomy in the therapeutic management of arthritis. World J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajarinen, J.; Lin, T.-H.; Sato, T.; Yao, Z.; Goodman, S. Interaction of materials and biology in total joint replacement–successes, challenges and future directions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 7094–7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tayar, J.H.; Suarez-Almazor, M.E. New understanding and approaches to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Br. Med Bull. 2010, 94, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shewaiter, M.A.; Hammady, T.M.; El-Gindy, A.; Hammadi, S.H.; Gad, S. Formulation and characterization of leflunomide/diclofenac sodium microemulsion base-gel for the transdermal treatment of inflammatory joint diseases. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Fenando, A. Sulfasalazine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.; Bell, M.J.; Ang, L.-C. Hydroxychloroquine neuromyotoxicity. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 2927–2931. [Google Scholar]

- Pers, Y.-M.; Padern, G. Revisiting the cardiovascular risk of hydroxychloroquine in RA. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 671–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, S. TNF inhibitor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed. Rep. 2013, 1, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramírez, J.; Cañete, J.D. Anakinra for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: A safety evaluation. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2018, 17, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.D.; Keystone, E. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol. Ther. 2015, 2, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blair, H.A.; Deeks, E.D. Abatacept: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 2017, 77, 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.J. Tocilizumab: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 2017, 77, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenders, M.I.; van den Berg, W.B. Secukinumab for rheumatology: Development and its potential place in therapy. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2016, 10, 2069–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Golbari, N.M.; Basehore, B.M.; Zito, P.M. Brodalumab. In StatPearls; © 2021; StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon, S. Tofacitinib: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 2017, 77, 1987–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salama, Z.T.; Scott, L.J. Baricitinib: A Review in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Drugs 2018, 78, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. A review of upadacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2020, 30, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oray, M.; Abu Samra, K.; Ebrahimiadib, N.; Meese, H.; Foster, C.S. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinescu, C.I.; Preda, M.B.; Burlacu, A. A procedure for in vitro evaluation of the immunosuppressive effect of mouse mesenchymal stem cells on activated T cell proliferation. Stem. Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushahary, D.; Spittler, A.; Kasper, C.; Weber, V.; Charwat, V. Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cytom. Part A 2018, 93, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xia, M.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells: An overview of their potential in cell-based therapy. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2015, 15, 1293–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.O. Comparison of molecular profiles of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, placenta and adipose tissue. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, Q.; Nakata, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Kasugai, S.; Kuroda, S. Comparison of gingiva-derived and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for osteogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 7592–7601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zupan, J. Human Synovium-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Ex Vivo Analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2045, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bari, C.; Dell’Accio, F.; Vanlauwe, J.; Eyckmans, J.; Khan, I.M.; Archer, C.W.; Jones, E.A.; McGonagle, D.; Mitsiadis, T.A.; Pitzalis, C. Mesenchymal multipotency of adult human periosteal cells demonstrated by single-cell lineage analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006, 54, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gaur, M.; Dobke, M.; Lunyak, V.V. Mesenchymal Stem Cells from Adipose Tissue in Clinical Applications for Dermatological Indications and Skin Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gan, L.; Liu, Y.; Cui, D.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, L.; Wan, M. Dental Tissue-Derived Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Potential in Therapeutic Application. Stem Cells Int. 2020, 2020, 8864572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieback, K.; Netsch, P. Isolation, culture, and characterization of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. In Mesenchymal Stem Cells; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Lanzillotti, C.; De Mattei, M.; Mazziotta, C.; Taraballi, F.; Rotondo, J.C.; Tognon, M.; Martini, F. Long Non-coding RNAs and MicroRNAs Interplay in Osteogenic Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 646032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz-Crawford, P.; Djouad, F.; Toupet, K.; Bony, C.; Franquesa, M.; Hoogduijn, M.J.; Jorgensen, C.; Noël, D. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist promotes macrophage polarization and inhibits B cell differentiation. Stem. Cells 2016, 34, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luz-Crawford, P.; Kurte, M.; Bravo-Alegría, J.; Contreras, R.; Nova-Lamperti, E.; Tejedor, G.; Noël, D.; Jorgensen, C.; Figueroa, F.; Djouad, F. Mesenchymal stem cells generate a CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cell population during the differentiation process of Th1 and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luque-Campos, N.; Contreras-López, R.A.; Jose Paredes-Martínez, M.; Torres, M.J.; Bahraoui, S.; Wei, M.; Espinoza, F.; Djouad, F.; Elizondo-Vega, R.J.; Luz-Crawford, P. Mesenchymal stem cells improve rheumatoid arthritis progression by controlling memory T cell response. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, Q.L. Mechanisms underlying the protective effects of mesenchymal stem cell-based therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2771–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.; He, X.; Zhao, R.; Guo, W.; Zhu, M.; Xing, W.; Jiang, D.; Liu, C.; Xu, X. Serum IFN-γ levels predict the therapeutic effect of mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in active rheumatoid arthritis. J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hong, J.; Hueckelhoven, A.; Wang, L.; Schmitt, A.; Wuchter, P.; Tabarkiewicz, J.; Kleist, C.; Bieback, K.; Ho, A.D.; Schmitt, M. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase mediates inhibition of virus-specific CD8(+) T cell proliferation by human mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, W.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, Z.; Ren, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Rabson, A.B.; Roberts, A.I.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y. Mesenchymal stem cells use IDO to regulate immunity in tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1576–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spaggiari, G.M.; Capobianco, A.; Abdelrazik, H.; Becchetti, F.; Mingari, M.C.; Moretta, L. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit natural killer-cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, and cytokine production: Role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and prostaglandin E2. Blood 2008, 111, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizoso, F.J.; Eiro, N.; Cid, S.; Schneider, J.; Perez-Fernandez, R. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Secretome: Toward Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategies in Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maffioli, E.; Nonnis, S.; Angioni, R.; Santagata, F.; Calì, B.; Zanotti, L.; Negri, A.; Viola, A.; Tedeschi, G. Proteomic analysis of the secretome of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells primed by pro-inflammatory cytokines. J. Proteom. 2017, 166, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.H.; Lee, B.C.; Choi, S.W.; Shin, J.H.; Kang, I.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, J.J.; Lee, H.K.; Jung, J.E.; Choi, Y.W.; et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate atopic dermatitis via regulation of B lymphocyte maturation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 512–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalinski, P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, G.; Cao, K.; Liu, K.; Xue, Y.; Roberts, A.I.; Li, F.; Han, Y.; Rabson, A.B.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y. Kynurenic acid, an IDO metabolite, controls TSG-6-mediated immunosuppression of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 1209–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, B.; Sun, Q.; Guo, S. Immunosuppressive Property of MSCs Mediated by Cell Surface Receptors. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleu, A.; Riffo-Vasquez, Y.; Trento, C.; Lomas, C.; Dolcetti, L.; Cheung, T.S.; von Bonin, M.; Barbieri, L.; Halai, K.; Ward, S.; et al. Apoptosis in mesenchymal stromal cells induces in vivo recipient-mediated immunomodulation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Preda, M.B.; Neculachi, C.A.; Fenyo, I.M.; Vacaru, A.-M.; Publik, M.A.; Simionescu, M.; Burlacu, A. Short lifespan of syngeneic transplanted MSC is a consequence of in vivo apoptosis and immune cell recruitment in mice. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothby, M.; Rickert, R.C. Metabolic Regulation of the Immune Humoral Response. Immunity 2017, 46, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Volkov, M.; van Schie, K.A.; van der Woude, D. Autoantibodies and B Cells: The ABC of rheumatoid arthritis pathophysiology. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 294, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shalini, P.U.; Vidyasagar, J.; Kona, L.K.; Ponnana, M.; Chelluri, L.K. In vitro allogeneic immune cell response to mesenchymal stromal cells derived from human adipose in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. Immunol. 2017, 314, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilev, G.; Ivanova, M.; Ivanova-Todorova, E.; Tumangelova-Yuzeir, K.; Krasimirova, E.; Stoilov, R.; Kyurkchiev, D. Secretory factors produced by adipose mesenchymal stem cells downregulate Th17 and increase Treg cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhou, P.-J.; He, Z.; Yan, H.-Z.; Xu, D.-D.; Wang, Y.; Fu, W.-Y.; Ruan, B.-B.; Wang, S. Use of immune modulation by human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells to treat experimental arthritis in mice. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2017, 9, 2595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Feng, T.; Gong, T.; Shen, C.; Zhu, T.; Wu, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, H. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the function of allogeneic activated Vγ9Vδ2 T lymphocytes in vitro. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinet, L.; Fleury-Cappellesso, S.; Gadelorge, M.; Dietrich, G.; Bourin, P.; Fournié, J.J.; Poupot, R. A regulatory cross-talk between Vγ9Vδ2 T lymphocytes and mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jawhari, J.; El-Sherbiny, Y.; Jones, E.; McGonagle, D. Mesenchymal stem cells, autoimmunity and rheumatoid arthritis. QJM 2014, 107, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hwang, J.J.; Rim, Y.A.; Nam, Y.; Ju, J.H. Recent Developments in Clinical Applications of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulherin, D.; Fitzgerald, O.; Bresnihan, B. Synovial tissue macrophage populations and articular damage in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 39, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udalova, I.A.; Mantovani, A.; Feldmann, M. Macrophage heterogeneity in the context of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam, A.; Mohammadian, S.; Vazini, H.; Taghadosi, M.; Esmaeili, S.A.; Mardani, F.; Seifi, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Afshari, J.T.; Sahebkar, A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kang, T.-W.; Lee, B.-C.; Lee, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Shin, J.-H.; Seo, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Lee, S. Human umbilical cord blood-stem cells direct macrophage polarization and block inflammasome activation to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, U.; Schett, G.; Bozec, A. How autoantibodies regulate osteoclast induced bone loss in rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bozec, A.; Luo, Y.; Engdahl, C.; Figueiredo, C.; Bang, H.; Schett, G. Abatacept blocks anti-citrullinated protein antibody and rheumatoid factor mediated cytokine production in human macrophages in IDO-dependent manner. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2018, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garimella, M.G.; Kour, S.; Piprode, V.; Mittal, M.; Kumar, A.; Rani, L.; Pote, S.T.; Mishra, G.C.; Chattopadhyay, N.; Wani, M.R. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells prevent systemic bone loss in collagen-induced arthritis. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 5136–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worbs, T.; Hammerschmidt, S.I.; Förster, R. Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Q.; Jie, H.; Lao, X.; Han, J.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Gu, D.; He, Y.; et al. FTY720 Abrogates Collagen-Induced Arthritis by Hindering Dendritic Cell Migration to Local Lymph Nodes. J. Immunol. 2015, 195, 4126–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, B.; Qi, J.; Yao, G.; Feng, R.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D.; Chen, C.; Tang, X.; Lu, L.; Chen, W. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation ameliorates Sjögren’s syndrome via suppressing IL-12 production by dendritic cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Peng, S.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, X.; Min, W. Synergistic suppression of autoimmune arthritis through concurrent treatment with tolerogenic DC and MSC. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.; Yoon, K.A.; Kang, T.W.; Jeon, H.J.; Sim, Y.B.; Choe, S.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Seo, K.W.; Kang, K.S. Therapeutic effect of long-interval repeated intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in DBA/1 mice with collagen-induced arthritis. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Farhoodi, H.P.; Han, M.; Liu, G.; Yu, J.; Nguyen, L.; Nguyen, B.; Nguyen, A.; Liao, W.; Zhao, W. Preclinical Evaluation of a Single Intravenous Infusion of hUC-MSC (BX-U001) in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cell Transplant. 2020, 29, 0963689720965896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalo-Gil, E.; Pérez-Lorenzo, M.J.; Galindo, M.; de la Guardia, R.D.; López-Millán, B.; Bueno, C.; Menéndez, P.; Pablos, J.L.; Criado, G. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate collagen-induced arthritis by inducing host-derived indoleamine 2, 3 dioxygenase. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Sun, Y.; Su, D.; Feng, X.; Gao, X.; Shi, S.; Chen, W. Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells inhibited T follicular helper cell generation in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrelli, A.; Van Wijk, F. CD8+ T cells in human autoimmune arthritis: The unusual suspects. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra, M.; Sharma, A.; Bagga, R.; Arora, S.K. Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells induce tissue repair and regeneration in collagen-induced arthritis in rats. J. Clin. Transl. Res. 2020, 6, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santalla, M.; Mancheño-Corvo, P.; Menta, R.; Lopez-Belmonte, J.; DelaRosa, O.; Bueren, J.A.; Dalemans, W.; Lombardo, E.; Garin, M.I. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells modulate experimental autoimmune arthritis by modifying early adaptive T cell responses. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Mu, R.; Wang, S.; Long, L.; Liu, X.; Li, R.; Sun, J.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Therapeutic potential of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2010, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.-H.; Wu, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, H.-b.; Zheng, R.-Q.; Wang, H.-L.; Yu, L.-N. Mesenchymal stem cells regulate the Th17/Treg cell balance partly through hepatocyte growth factor in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haikal, S.M.; Abdeltawab, N.F.; Rashed, L.A.; El-Galil, A.; Tarek, I.; Elmalt, H.A.; Amin, M.A. Combination therapy of mesenchymal stromal cells and interleukin-4 attenuates rheumatoid arthritis in a collagen-induced murine model. Cells 2019, 8, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, F.K.; Stefan, A.; Kay, A.G.; Hyland, M.; Morgan, R.; Forsyth, N.R.; Pisconti, A.; Kehoe, O. Syndecan-3 regulates MSC adhesion, ERK and AKT signalling in vitro and its deletion enhances MSC efficacy in a model of inflammatory arthritis in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Santalla, M.; Fernandez-Perez, R.; Garin, M.I. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells for rheumatoid arthritis treatment: An update on clinical applications. Cells 2020, 9, 1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Li, L. Preconditioning influences mesenchymal stem cell properties in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Raziyeva, K.; Smagulova, A.; Kim, Y.; Smagul, S.; Nurkesh, A.; Saparov, A. Preconditioned and genetically modified stem cells for myocardial infarction treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saparov, A.; Ogay, V.; Nurgozhin, T.; Jumabay, M.; Chen, W.C. Preconditioning of human mesenchymal stem cells to enhance their regulation of the immune response. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansurov, N.; Chen, W.C.; Awada, H.; Huard, J.; Wang, Y.; Saparov, A. A controlled release system for simultaneous delivery of three human perivascular stem cell-derived factors for tissue repair and regeneration. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, e1164–e1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Cássia Noronha, N.; Mizukami, A.; Caliári-Oliveira, C.; Cominal, J.G.; Rocha, J.L.M.; Covas, D.T.; Swiech, K.; Malmegrim, K.C. Priming approaches to improve the efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.S.; Suryaprakash, S.; Lao, Y.-H.; Leong, K.W. Engineering mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine and drug delivery. Methods 2015, 84, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lim, J.-Y.; Im, K.-I.; Lee, E.-S.; Kim, N.; Nam, Y.-S.; Jeon, Y.-W.; Cho, S.-G. Enhanced immunoregulation of mesenchymal stem cells by IL-10-producing type 1 regulatory T cells in collagen-induced arthritis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrenko, Y.; Syková, E.; Kubinová, Š. The therapeutic potential of three-dimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell spheroids. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartosh, T.J.; Ylöstalo, J.H.; Bazhanov, N.; Kuhlman, J.; Prockop, D.J. Dynamic compaction of human mesenchymal stem/precursor cells into spheres self-activates caspase-dependent IL1 signaling to enhance secretion of modulators of inflammation and immunity (PGE2, TSG6, and STC1). Stem Cells 2013, 31, 2443–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmermann, J.A.; Mcdevitt, T.C. Pre-conditioning mesenchymal stromal cell spheroids for immunomodulatory paracrine factor secretion. Cytotherapy 2014, 16, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, R.A.; Figueroa, F.E.; Djouad, F.; Luz-Crawford, P. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulate the Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses Dampening Arthritis Progression. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 3162743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, I.; Gómez-Aristizábal, A.; Wang, X.H.; Viswanathan, S.; Keating, A. TLR3 or TLR4 activation enhances mesenchymal stromal cell-mediated Treg induction via Notch signaling. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Lee, W.H.; Lee, M.W.; Park, H.J.; Jang, I.K.; Lee, J.W.; Sung, K.W.; Koo, H.H.; Yoo, K.H. Involvement of TLR3-dependent PGES expression in immunosuppression by human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffary, E.M.; Froushani, S.M.A. Immunomodulatory benefits of mesenchymal stem cells treated with caffeine in adjuvant-induced arthritis. Life Sci. 2020, 246, 117420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ge, H.-a.; Wu, G.-b.; Cheng, B.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, C. Autophagy prevents oxidative stress-induced loss of self-renewal capacity and stemness in human tendon stem cells by reducing ROS accumulation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 2227–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Tan, H. Hypoxia-induced secretion of IL-10 from adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell promotes growth and cancer stem cell properties of Burkitt lymphoma. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 7835–7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhijn, R.-V.; Mensah, F.K.; Korevaar, S.S.; Leijs, M.J.; van Osch, G.J.; IJzermans, J.N.; Betjes, M.G.; Baan, C.C.; Weimar, W.; Hoogduijn, M.J. Effects of hypoxia on the immunomodulatory properties of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Ogay, V.; Sekenova, A.; Li, Y.; Issabekova, A.; Saparov, A. The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 16, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgun, C.; Ceresa, D.; Lesage, R.; Villa, F.; Reverberi, D.; Balbi, C.; Santamaria, S.; Cortese, K.; Malatesta, P.; Geris, L.; et al. Dissecting the effects of preconditioning with inflammatory cytokines and hypoxia on the angiogenic potential of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-derived soluble proteins and extracellular vesicles (EVs). Biomaterials 2021, 269, 120633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Shen, M.; Yang, M.; Jin, Z.; Ding, L.; Jiang, W.; Yang, J.; Chen, H.; Cao, F.; et al. Autophagy mediates the beneficial effect of hypoxic preconditioning on bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells for the therapy of myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wobma, H.M.; Kanai, M.; Ma, S.P.; Shih, Y.; Li, H.W.; Duran-Struuck, R.; Winchester, R.; Goeta, S.; Brown, L.M.; Vunjak-Novakovic, G. Dual IFN-γ/hypoxia priming enhances immunosuppression of mesenchymal stromal cells through regulatory proteins and metabolic mechanisms. J. Immunol. Regen. Med. 2018, 1, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noone, C.; Kihm, A.; English, K.; O′Dea, S.; Mahon, B.P. IFN-γ stimulated human umbilical-tissue-derived cells potently suppress NK activation and resist NK-mediated cytotoxicity in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 3003–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.É.S.; Sousa, M.R.R.; Alencar-Silva, T.; Carvalho, J.L.; Saldanha-Araujo, F. Mesenchymal stem cells immunomodulation: The road to IFN-γ licensing and the path ahead. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2019, 47, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, D.; Suhr, L.; Wahlers, T.; Choi, Y.H.; Paunel-Görgülü, A. Preconditioning of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells highly strengthens their potential to promote IL-6-dependent M2b polarization. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redondo-Castro, E.; Cunningham, C.; Miller, J.; Martuscelli, L.; Aoulad-Ali, S.; Rothwell, N.J.; Kielty, C.M.; Allan, S.M.; Pinteaux, E. Interleukin-1 primes human mesenchymal stem cells towards an anti-inflammatory and pro-trophic phenotype in vitro. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnadurai, R.; Copland, I.B.; Patel, S.R.; Galipeau, J. IDO-independent suppression of T cell effector function by IFN-γ–licensed human mesenchymal stromal cells. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanathan, K.N.; Rojas-Canales, D.M.; Hope, C.M.; Krishnan, R.; Carroll, R.P.; Gronthos, S.; Grey, S.T.; Coates, P.T. Interleukin-17A-Induced Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Are Superior Modulators of Immunological Function. Stem Cells 2015, 33, 2850–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Drug | Example | Administration/Dose | Mechanism of Action | Side Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Synthetic DMARDs | MTX | Orally or intravenous (IV) injection (15 mg), single subcutaneous (SC) or intramuscular (IM) injection (15–25 mg/week) | Impairs purine and pyrimidine metabolism, inhibits amino acid and polyamine synthesis | Skin cancer and gastrointestinal, infectious, pulmonary and hematologic side effects, bone marrow impairments | [27,28] |

| Leflunomide | Orally (50 mg/week or 10 mg/day) | Inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase enzyme leading to inhibition de novo synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides | Dyspepsia, nausea, abdominal pain and oral ulceration | [72] | |

| Sulfasalazine | Orally (500 mg/daily or 1 g/day in 2 divided doses up to a maximum of 3 g/day in divided doses) | Suppresses the transcription of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) responsive pro-inflammatory genes including TNF-α | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, dyspepsia, male infertility (reversible), headache and skin rash | [73] | |

| Hydroxychloroquine | Orally (400 mg/day over a 30-day period) | Increases pH within intracellular vacuoles and alters processes such as protein degradation by acidic hydrolases in the lysosome, assembly of macromolecules in the endosomes and post-translation modification of proteins in the Golgi apparatus | Retinal toxicity, neuromyotoxicity | [74,75] | |

| Biologic DMARDs | Etanercept, Infliximab, Adalimumab, Golimumab, Certolizuma-bpegol | Etanercept—SC injection (50 mg/week or 25 mg/twice a week); Infliximab—SC injection (3–10 mg/kg every 4–8 weeks); Adalimumab—SC injection (25 mg/twice a week); Golimumab—SC injection (50mg/month); Certolizumab pegol—SC injection (400 mg at weeks 0, 2 and 4, followed by 200 mg every 2 weeks) | Blocks the biological activity of TNF | Infections, neurological diseases, development of multiple sclerosis and lymphomas | [76] |

| Anakinra | SC injection (75–150 mg or 0.04–2 mg/kg) | Binds to IL-1 receptors | Opportunistic and latent infections | [77] | |

| Rituximab | IV injection (1 gm twice separated by 2 weeks) with MTX and IV corticosteroid premedication | Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody | Hypogammaglobulinemia, rarely serious infectious events | [78] | |

| Abatacept | IV injection (2–10 mg/kg on days 1, 15 and 30, and then every 4 weeks) | Contains the domain of cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), blocks interaction between DCs and T cells | Serious infections, increased risk of certain malignancies | [79] | |

| Tocilizumab | IV injection (8 mg/kg once every 4 weeks) or SC injection (162 mg/week) | Blocks IL-6 receptor | Serious infections, major adverse cardiovascular events, cancers, diverticular perforations, hepatic diseases, rarely lethal | [80] | |

| Secukinumab | SC injections (25–300 mg) | Primarily targets IL-17A | Nasopharyngitis or infections of the upper respiratory tract, mild-to-moderate candidiasis | [81] | |

| Brodalumab | SC injection (70–210 mg) | Prevents the nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells, IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, MMPs and GM-CSF | Nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, arthralgia, back pain, gastroenteritis, influenza, oropharyngeal pain, sinusitis | [82] | |

| Targeted Synthetic DMARDs | Tofacitinib | Orally (5 mg/twice daily) | Blocks Janus kinases (JAK1 and JAK3) | Cardiovascular events, neutropenia and lymphopenia, risk of infection (viral reactivation, herpes virus reactivation, opportunistic infections) | [83] |

| Baricitinib | Orally (4 mg/day or lower dosage 2 mg/day) | Inhibits JAK1/JAK2 | Hyperlipidemia, viral reactivation, deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism event | [84] | |

| Upadacitinib | Orally (15 mg/day or 30 mg/day) | Inhibits JAK1 | Upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal perforation | [85] | |

| GCs | Dexame-thasone, be-tamethasone, triamcinolone, prednisone, prednisolone | The addition of GCs, to either standard DMARD monotherapy or combinations of synthetic DMARDs with low-dose GCs (< 7.5 mg/day) or high-dose GCs (up to 15 mg/day) | Directly activates or represses gene transcription | Ecchymosis, cushingoid features, parchment-like skin, leg edema, sleep disturbance, immunosuppression, weight gain, epistaxis, glaucoma, depression, hypertension, diabetes | [40,41,86] |

| RA Model | Source and Tissue Origin of MSCs | Route of Administration/Number of Repetitions | Dosage | Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIA in DBA1/J mice | hUCB MSCs | IP injections for 5 days after the RA score reached 3 or more | 1 × 106 cells | hUCB MSCs polarized M1 macrophages toward M2 phenotype through TNF-α-mediated activation of COX-2 and TSG-6 | Amelioration of the severity of CIA | [127] |

| CIA in DBA/1J mice | hBM MSCs | IP injection on day 22 after primary immunization | 2 × 106 cells | hBM MSCs inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis | Amelioration of inflammation-induced systemic bone loss in CIA | [130] |

| CIA in DBA1/J mice | hUC MSCs | IV injection on day 28 after RA score reached 1 or more | 1 × 106 cells | hUC MSCs reduced number and downregulated function of Tfh cells in the spleen accompanied with decreased Th1 and Th17 cells | Prevention of CIA progression | [138] |

| CIA in DBA/1OlaHsd mice | hESC MSCs | Single-dose IP injection on the day of immunization (prophylaxis) or with three doses of hESC MSCs every other day starting on the day of arthritis onset (therapy) | 1 × 106 cells | hESC MSCs increased the number of FoxP3(+) Tregs and IFN-γ+ Th1 cells but not Th17, additionally induced the expression of IDO1 in inguinal lymph nodes | Reduction of disease progression and severity of CIA | [137] |

| CIA in DBA1/J mice | hUCB MSCs | IV injection of three different doses every 2 weeks, overall, three times | 1 × 106 cells, 3 × 106 cells, 5 × 106 cells | hUCB MSCs decreased IL-1β and IL-6 levels; concentration of 5×106 hUCB MSCs increased the level of IL-10 production and the expansion of Tregs | Alleviation of RA symptoms in a CIA model | [135] |

| CIA in DBA1/J mice | hUC MSCs | IV injection after 24 days after RA induction | 2 × 106 cells | hUC MSCs reduced the level of IL-6 by 80.0% 2 days after treatment and by 93.4% at the endpoint | Relief of RA disease symptoms in a CIA model | [136] |

| CIA in DBA/1 mice | hAT MSCs | IV injection on day 28 after arthritis induction for the next five days | 2 × 106 cells | hAT MSCs induced the expansion of Tregs both in the peripheral blood and spleen (in vivo); and downregulated the level of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in mouse macrophages and inhibited the proliferation of human primary T cells (in vitro) | Attenuation of systemic inflammation in mice with CIA | [119] |

| CIA in Balb/c mice | Murine BM MSCs | IV injection of MSCs and IP injection of IL-4 at day 21 | 5 × 106 cells | BM MSCs in combination with IL-4 treatment decreased the levels of RF, C-reactive protein (CRP) and anti-nuclear antibodies; TNF-α and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) levels. Additionally, BM MSCs decreased the levels of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (Comp), tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1 (Timp1), MMP-1 and IL-1 receptor | Reduction of joint inflammation, synovial cellularity, vascularization and bone destruction in a CIA model | [144] |

| CIA in female Wistar rats | hUC MSCs | IP injection on days 16 and 18 | 2 × 106 cells | hUC MSCs downregulated the functions of activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, suppressed the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and induced the expansion of Tregs | Slowing down the progression of disease activity | [140] |

| Clinical Trial Identifier | Study Design | Cell Source | Number of Patients | Route of Administration and Doses | Follow-Up Time (Months) | Clinical Status before Treatment or Control Group | Clinical Status after Treatment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01663116 | Randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation phase Ib/IIa | Allogeneic AT MSCs | 53 | 1, 2 or 4 × 106 cells/kg of body weight, three IV injections, weekly | 6 | DAS28-ESR↑, CRP↑, ACR20 response after 1 month (29%) and 3 month (0%) | DAS28-ESR↓, CRP↓, ACR20 response after 1 month (20–45%) and 3 month (15–25%) | [16] |

| Unknown | Pilot | Autologous AT MSCs | 3 | Patient 1: two separate IV injections of 3 × 108 cells, 15 week interval Patient 2: once 2 × 108 cells (IV injection) + 1 × 108 cells (IA injection); once 3.5 × 108 cells (IV injection) + 1.5 × 108 cells (IA injection), 3-month interval Patient 3: four separate IV injection of 2 × 108 cells, 4-week interval | 3–13 | VAS↑, KWOMAC↑, CRP↑, RF↑, anti-CCP↑, Standing time↓, WD↓ | VAS↓, KWOMAC↓, CRP↓, RF↓, anti-CCP↓, standing time↑, WD↑, off steroids | [17] |

| NCT03333681 | Phase I | Autologous BM MSCs | 9 | 1 to 2 × 106 cells/kg of body weight, single IV injection | 12 | DAS28-ESR↑, VAS↑, ESR↑, CRP↑, RF↑, anti-CCP↑ | DAS28-ESR↓, VAS↓, ESR↓, CRP↓(NS), RF↓, anti-CCP↓ (NS) | [18] |

| NCT01873625 | Randomized, triple-blind, single-center, placebo-controlled phase I/II | Autologous BM MSCs | 30 | 4.2 × 107 cells/patient, single IA injection | 12 | DAS28↑, VAS↑, WOMAC↑, ESR↑, CRP↑, Pain FWD↓, WD↓, Time to jelling↓, Standing time↓ | DAS28↓ (NS), VAS↓, WOMAC↓, ESR↓ (NS), CRP↓ (NS), Pain FWD↑, WD↑, Time to jelling↑, Standing time↑ | [19] |

| NCT01547091 | Prospective phase I/II | Allogeneic UC MSCs | 172 | 4 × 107 cells/patient, single IV injection | 36 | DAS28↑, HAQ↑, CRP↑, ESR↑, RF↑, anti-CCP↑, TNF-α↑, IL-6↑ | DAS28↓, HAQ↓, CRP↓, ESR↓, RF↓, anti-CCP↑, TNF-α↓, IL-6↓ | [20,21] |

| NCT02221258 | Phase Ia, open-label, dose-escalation | Allogeneic UCB MSCs | 9 | 2.5 × 107, 5 × 107, or 1 × 108 cells/patient, single IV injection | 1 | DAS28↑, VAS↑, HAQ↑, CRP↑, IL-1β↑, IL-6↑, IL-8↑, TNF-α↑ | DAS28↓, VAS↓, HAQ↓, CRP↓, IL-1β↓, IL-6↓, IL-8↓, TNF-α↓ | [22] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarsenova, M.; Issabekova, A.; Abisheva, S.; Rutskaya-Moroshan, K.; Ogay, V.; Saparov, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111592

Sarsenova M, Issabekova A, Abisheva S, Rutskaya-Moroshan K, Ogay V, Saparov A. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021; 22(21):11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111592

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarsenova, Madina, Assel Issabekova, Saule Abisheva, Kristina Rutskaya-Moroshan, Vyacheslav Ogay, and Arman Saparov. 2021. "Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22, no. 21: 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111592

APA StyleSarsenova, M., Issabekova, A., Abisheva, S., Rutskaya-Moroshan, K., Ogay, V., & Saparov, A. (2021). Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(21), 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111592